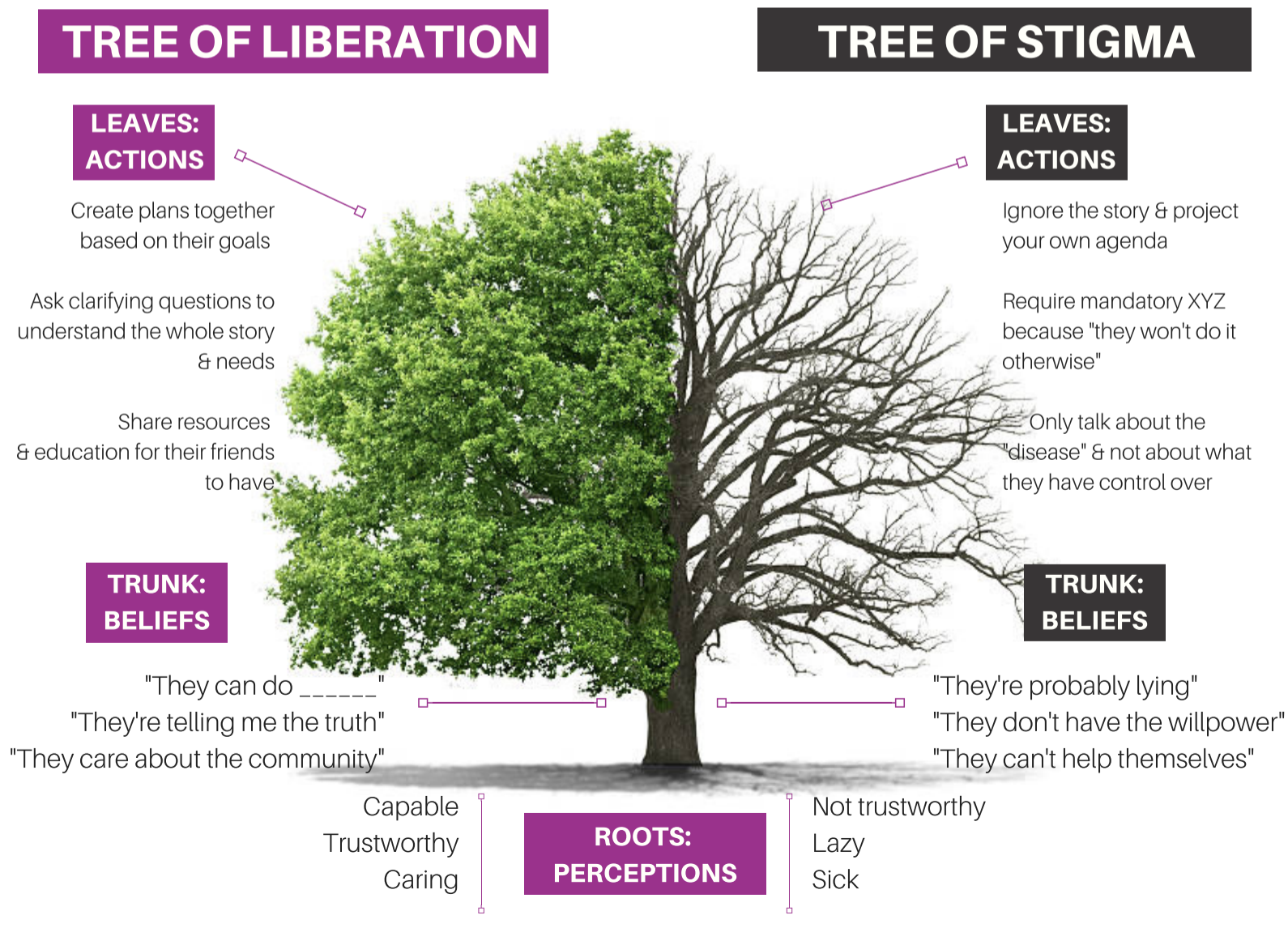

I recently stumbled on this educational page about stigma from the National Harm Reduction Coalition.

It’s well done and illuminates the assumptions and goals for their stigma reduction efforts. They frame responding to drug use as a choice between liberation and stigma, with harm reduction as the path to liberation.

While it may work for many (maybe most) people who use drugs, I’m concerned that it doesn’t work well for people with addiction and might require some modification if it’s intended to be helpful to this minority of people who use drugs.

They define stigma as follows:

Stigma is a social process linked to power and control, which leads to creating stereotypes and assigning labels to those that are considered to deviate from the norm or to behave “badly.” Stigma creates the social conditions that make people who use drugs believe they are not deserving of being treated with dignity and respect, perpetuating feelings of fear and isolation.

I’d emphasize isolation from their definition. To me, that is the essence of stigmatization. I see it as an evolutionary reaction to perceived threats, seeking to isolate the perceived threat from the rest of the community. That threat could be a disease, a behavior, or anything that might appear to be a threat to the health, function, structure, status, or social order of the community. (It’s important to recognize that something doesn’t need to be an actual threat and that evolution would favor the over-identification of threats. Further, many false positives will probably be aligned with the prevailing social structures, and ones that are not will often have post-hoc explanations that are aligned with those structures.)

In their framework, the goal for people who use drugs is liberation, which is described as such:

Liberation is the act of setting someone free from imprisonment, slavery or oppression.

In the context of drug use and sex work, liberation is about freedom from thoughts or behavior — ”the way it’s supposed to be” — and how we are conditioned to perpetuate harms to others.

The first statement emphasizes freedom — freedom from external forces infringing on liberty and dignity. The second statement adds freedom from harmful traditions and orthodoxies.

This strikes me as a place where it’s important to distinguish between people with addiction and other people who use drugs.

The elements above may provide a pathway to liberation from social responses to a freely chosen behavior. And, for most people who use drugs, it is freely chosen behavior.

The illness of addiction, however, is characterized by impaired control over use. Further, the experience of impaired control over drug use is an experience of oppression. This illness and impaired control constitutes a barrier to a life organized around the person’s goals, values, and priorities. These barriers extend into all areas of life — the relational, occupational, emotional, moral, civic, and spiritual selves.

Where the illness of addiction is present, freedom from external oppression cannot deliver liberation, though it may remove some barriers to liberation and recovery.

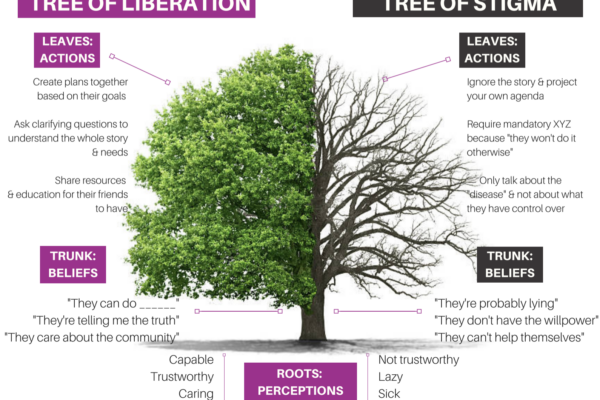

So, how might this change the tree of stigma?

My previous posts on recovery-oriented harm reduction shed some light on my ideas. However, reviewing the tree of stigma got me thinking that, while I differentiated drug use in addiction from other drug use, I didn’t speak explicitly enough to drug use by people without addiction.

Most drug use is not addiction. There is a broad spectrum of alcohol and other drug use. Addiction is at the extreme of the problematic end of that spectrum. We should not presume that the principles that apply to the problem of addiction are applicable to other AOD use.

ROHR is committed to improving the wellbeing of all people who use drugs. ROHR services are not contingent on current AOD use, recovery status, motivation, or goals. Further, their dignity, respect, and concern for their rights are not contingent on any of these factors.

Addiction is an illness. The defining characteristic of the disease of addiction is impaired control related to their substance use. We should not presume that the principles that apply to other people who use drugs will be applicable to people with addiction.

Drug use in addiction is not freely chosen. Because the disease of addiction affects the ability to choose, drug use by people with addiction should not be viewed as a lifestyle choice or manifestation of free will to be protected. It is not a expression of personal liberty, it is a symptom of an illness and indicates compromised personal agency.

An emphasis on client choice—no coercion. While addiction indicates an impaired ability to make choices about AOD use, service providers should not engage in coercive tactics to engage clients in services. Service engagement should be voluntary. Where other systems (legal, professional, child protection, etc.) use coercive pressure, service providers should be cautious that they do not participate in the disenfranchisement or stigmatization of people with addiction. Some might wonder whether ROHR is appropriate for people who use drugs and recovery is not an appropriate endpoint. (Because it isn’t indicated and/or wanted.) Its goal is to assure that hope and a visible pathway to full and stable recovery is available to all for whom it is indicated, but never to impose it.

For those with addiction, full recovery is the ideal outcome. People with addiction, the systems that work with them, and the people around them often begin to lower expectations for recovery. In some cases, this professional despair emerges in the context of inadequate resources. In others, it stems from working in systems that never offer an opportunity to witness recovery. Whatever the reason, maintaining a vision of full recovery (complete and enduring cessation of all AOD-related problems and the movement toward global health) as the ideal outcome is critical. Just as we would for any other treatable chronic illness.

The concept of recovery can be inclusive — it can include partial, serial, etc. While my ROHR writing has argued for a distinction between recovery and harm reduction, Bill White has described paths that can be considered precursors (precovery) to full recovery.

Recovery is possible for any person with addiction. ROHR refuses cultural, institutional, or professional pressures to treat any sub-population as incapable of recovery. ROHR recognizes the humbling experiential wisdom that many recovering people once had an abysmal clinical prognosis.

All services for people with addiction should communicate hope for recovery. ROHR recognizes that hope-based interventions are essential for enhancing motivation to recover and for developing community-based recovery capital. Practitioners can maintain a nonjudgmental and warm approach with active AOD use while also conveying hope for recovery. All ROHR services should inventory the signals they send to individuals and the community. As Scott Kellogg says, “at some point, you need to help build a life after you’ve saved one.”

Incremental and radical change should be supported and affirmed. As the concepts of gradualism and precovery indicate, recovery often begins with small incremental steps. These steps should not be dismissed or judged as inadequate. They should be supported and celebrated as personal accomplishments and they should not be treated as a clinical endpoint. Likewise, radical change should not be dismissed as unrealistic or unsustainable pathology.

ROHR looks beyond the individual and public health when attempting to reduce harm. ROHR wrestles with whether public health is being protected at the expense of people with addiction, whether harm is being sustained to families and communities, and whether an intervention has implications for recovery landscapes. It recognizes that the interests of people with addiction and other people who use drugs will diverge in many cases. ROHR maintains deliberate awareness of this reality and refuses to sacrifice one group for the other.

ROHR should aggressively address counter-transference. ROHR recognizes a history of providers imposing their own recovery path on clients while others enjoy vicarious nonconformity or transgression through clients. Substance use workers of all orientations are vulnerable to savior and martyr complexes. These tendencies should be openly discussed and addressed during training and ongoing supervision.

ROHR refuses to allow recovery and HR to be framed as counterforces to each other. While recognizing that most people who use drugs do not need or want recovery, for those with addiction, ROHR seeks to be a bridge to recovery and lower thresholds to recovery and avoids positioning itself as a counterforce to recovery. Recognizing that addiction/recovery has become a front in culture wars, ROHR seeks to address barriers while also being sensitive to the barriers that can be created in this context. When ROHR seeks to question the status quo, it is especially wary of attempts to differentiate from recovery that deploy strawmen, recognizing that this rhetoric is harmful to recovering communities and, therefore, to their clients’ chances of achieving stable recovery.

ROHR recognizes harm reduction can be an appropriate end for many people who use drugs, but is better pursued as a means to an end for people with addiction. ROHR views harm reduction as strategies, interventions, and ideas to reduce harm. As such, it is wary of models that frame harm reduction as an end unto itself for people with addiction. Back to Scott Kellogg’s point, “at some point, you need to help build a life after you’ve saved one.” The end we seek is recovery, or restoration, or flourishing, whatever is most appropriate for the individual or group. ROHR maintains awareness of tendencies to view harm reduction as “the thing” rather than “the thing that gets us to the thing.”

None of this is intended to suggest that anything here is bad or wrong. In the absence of addiction, this model makes a lot of sense. For most people who use drugs, it makes a lot of sense.

Historically, we failed to do a good job distinguishing between addiction and other drug use, erring on the side of categorizing far too much drug use as addictive. Appropriately, people have sought to correct this problem via professional, academic, and cultural change. (I’ve previously shared concerns about the DSM 5’s effect on the differentiation of addiction from other drug problems.) Unfortunately, this correction has resulted in the erasure of the distinction in many spaces.

This has been a good thing for people who had previously been miscategorized. They are more likely to be left alone and, where appropriate, get help that doesn’t presume addiction is the problem.

However, I’m increasingly concerned about the needs of people with addiction having their needs understood, respected, and responded to appropriately.

As the spectrum of drug use is increasingly being professionally, academically, and culturally understood as a manifestation of liberty and free choice, people with impaired control are likely to be misunderstood and stigmatized.

There’s no inherent incompatibility, but there is some tension. The needs and interests of people without addiction who use drugs, people with addiction who use drugs, people in recovery from addiction, the loved ones of those three groups, and the communities/communities of those three groups are not always aligned.

Recognizing these misaligned needs/interests is essential to developing models, systems, and policies that consider and respond to the needs of everyone. This would be important if these were stable and discrete categories, but the need seems even more important when we consider that people may move through these categories and may be in more than one category at the same time.