There is and can be no ultimate solution for us to discover, but instead a permanent need for balancing contradictory claims, for careful trade-offs between conflicting values, toleration of difference, consideration of the specific factors at play when a choice is needed, not reliance on an abstract blueprint claimed to be applicable everywhere, always, to all people.

A recent Health Affairs article by Nora Volkow about non-abstinence endpoints for addiction treatments has received a lot of attention. Some are hailing it as a long-overdue change of course and others have expressed concern that it represents a step in the direction of abandoning recovery.

Personally, I don’t see this as an especially noteworthy event for a few reasons:

- As linked to in the article, Nora Volkow has called for alternative endpoints nearly 4 years and has advocated for broader use of medication to treat substance use disorders (SUDs) on the basis of non-abstinence outcomes for more than a decade.

- The FDA issued guidance with non-abstinence endpoints years ago.

- The idea that complete abstinence is the metric for medically-assisted treatment (MAT) effectiveness is just not true. I reviewed some of the most frequently cited evidence for MAT and most studies don’t even report information on abstinence.

Different in kind or severity?

The article commits one of my pet peeves by using both “addiction” and “use disorder” interchangeably, without distinguishing between the different kinds and severities of substance problems. This is always important but it seems particularly important when discussing treatment endpoints.

I’ve written at length about how important I believe it is to recognize different kinds of substance problems rather than just different severities and the implications of the DSM 5’s shift from a categorical model of alcohol problems to a continuum model. In short, I believe addiction (the most severe and chronic form) is not just a more severe version of other alcohol and other drug problems, I believe it’s a different category of problem.

However, DSM 5 put all substance problems were put on a single continuum, meaning low severity problems share the same diagnosis as high severity, high chronicity alcohol problems. I see this as akin to rolling all respiratory diseases into “respiratory disorder” as a diagnostic category. The different kinds and categories of respiratory diagnoses have profound implications for determining the prognosis and treatment plan.

For example, for high severity, high chronicity problems (addiction), abstinence has long been considered the most appropriate treatment goal, while moderation has been considered an appropriate goal for low to moderate severity problems. (See here, here, and here for examples.)

Non-abstinence endpoints?

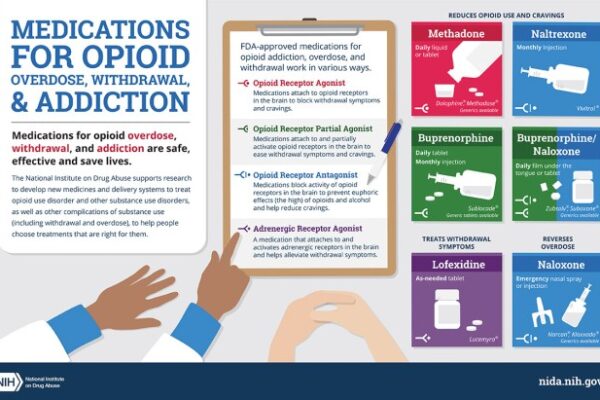

As stated above, non-abstinence outcomes have long been widely accepted as reasons to adopt and expand the use of medications. In fact, those outcomes have become the basis for big federally and foundation funded projects, like expanding low-threshold buprenorphine prescribing in emergency departments.

So… where’s the controversy?

I’m not up on the details of the FDA approval process, but if there have been barriers to getting treatments approved to achieve these endpoints, clearing those barriers is a good thing, particularly in the context of the OD crisis.

First of all, non-abstinence endpoints will align well with the desired treatment outcomes and full functioning for most people with alcohol and other drug problems.

For others, for whom abstinence is necessary for sustained recovery, non-abstinence endpoints may: 1) be useful in the process of determining whether abstinence is necessary for sustained recovery; 2) represent an incremental step toward abstinence; 3) accomplish harm reduction goals; 4) represent one element of a much more comprehensive treatment plan; 5) represent deference to patient preferences.

The OD crisis has increased the stakes, making it clear that we can’t allow the best (for some) to be the enemy of the good. I suppose it’s also possible that an open embrace of these endpoints could result in better informed consent. Some of the tension around non-abstinence endpoints can be attributed to one-wayers who think everyone needs and should only be offered treatments focused on immediate abstinence. However, much more often, I think the tension is related a misalignment between the desired outcomes for patients and families dealing with the high severity/chronicity type, the demonstrated outcomes for the treatment, and the way that information is presented to patients and families.

Looking ahead

So… if non-abstinence endpoints are already well established in research and practice, we’re all set, right? Not quite.

Despite the establishment of these endpoints, there has been some resistance and ambivalence, which I think can be attributed to two factors.

The first is whether they lower expectations for full, sustained recovery. Here, Eric Strain questions whether the field has been ambitious enough on behalf of our patients.

This focus on opioid overdose deaths is overlooking the importance of doing more to help people than preventing a death. Not overdosing is an insufficient endpoint for treatment or for societal and medical interventions – it’s a starting point. We fool ourselves and do a disservice to patients if we allow this to be the measure that allows us to declare success. If a patient with a significant leg wound has the bleeding stopped with a compress, the medical field does not declare victory. Providers clean the wound, stitch it, arrange for physical therapy for the leg, and work to maximize the functioning of the person.

He goes on to call for flourishing as the goal for patients with alcohol and other drug problems.

We should fight to ensure our patients and this field does not accept anything less than flourishing – that should be the goal we bring to our work in research and clinical practice.

One of the major challenges we face is understanding and agreeing upon what’s required to achieve flourishing.

For people with low to moderate severity, eliminating binges or reducing heavy drinking days may be all that is required to make flourishing possible.

For others, like most with addiction, reduced use of opioids will not deliver the improvements in quality of life that they and their loved ones want. Bill White addresses why recovery from addiction can’t be achieved through subtraction of symptoms.

Recovery from opioid addiction is also more than remission, with remission defined as the sustained cessation or deceleration of opioid and other drug use/problems to a subclinical level—no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for opioid dependence or another substance use disorder. Remission is about the subtraction of pathology; recovery is ultimately about the achievement of global (physical, emotional, relational, spiritual) health, social functioning, and quality of life in the community.

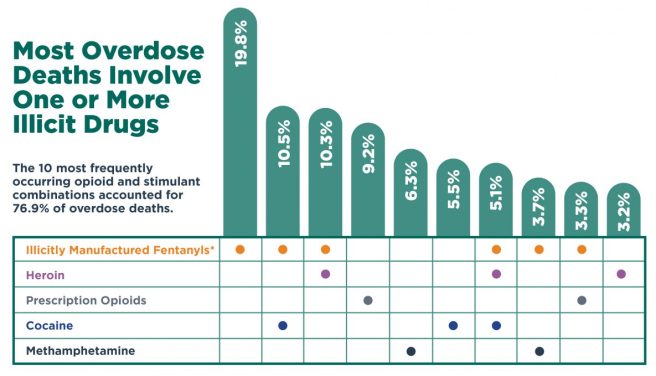

Further, for most with addiction, their problem is not multiple distinct substance use disorders like, opioid use disorder, stimulant use disorder, and alcohol use disorder. Their problem is addiction. Treatments targeting individual use disorders too often miss the nature of the problem and set the stage for outcomes where the surgery might be deemed a success but the patient dies.

This brings us to the second factor, distinguishing between patients for whom abstinence is necessary for full, sustained recovery, and those who can achieve flourishing without abstinence.

Dirk Hanson describes how dynamics in the current drug policy and addiction space have made the differences between these types of alcohol and other drug problems fuzzier rather than clearer.

For harm reductionists, addiction is sometimes viewed as a learning disorder. This semantic construction seems to hold out the possibility of learning to drink or use drugs moderately after using them addictively. The fact that some non-alcoholics drink too much and ought to cut back, just as some recreational drug users need to ease up, is certainly a public health issue—but one that is distinct in almost every way from the issue of biochemical addiction. By concentrating on the fuzziest part of the spectrum, where problem drinking merges into alcoholism, we’ve introduced fuzzy thinking with regard to at least some of the existing addiction research base. And that doesn’t help anybody find common ground.

So… as I’ve said above and elsewhere, I think we’d do ourselves a big favor by returning to thinking about alcohol and other drug problems in terms of categories rather than a spectrum. Academics and researchers could do a valuable public service by not using abuse, dependence, SUD, and addiction interchangeably and explaining to readers what type of alcohol and other drug problem they are researching, treating, and discussing.

Why does anyone care about abstinence?

This brings me to another thought about how to move forward.

The spectrum approach has not only introduced fuzziness into understanding the types of alcohol and other drug problems, it’s also introduced fuzziness into our understanding of recovery.

I’m not aware of any historical movement of people with low to moderate severity alcohol and other drug problems identifying themselves as “in recovery”, but academics and advocates have expanded the category to anyone who identifies as once having had a substance problem and no longer does. This, of course, added millions who, for example, engaged in excessive use as a young adult and moderated or quit on their own. This didn’t just add numbers of people to the category of recovery, but changed how recovery had historically been understood.

Recovery had historically been limited to those with the most severe alcohol and other drug problems (addiction) characterized by impaired control over the quantity used, amount of time spent using, and/or whether or not they used. These people had tried moderation and/or eliminating some substances but not others. However, their addiction and it’s hallmark of impaired control made abstinence the only path to full sustained recovery.

This is not a moral decision, it’s a practical decision based on extensive experience and suffering.

This brings me to why I think Volkow’s article got so much attention.

Healthcare and society must move beyond this dichotomous, moralistic view of drug use and abstinence and the judgmental attitudes and practices that go with it.

“Making Addiction Treatment More Realistic And Pragmatic“,

Health Affairs Forefront, January 3, 2022.

The linking of abstinence to moralistic and judgmental attitudes and practices plays into culture war battles that consume too much energy and attention within the field. I don’t think this was her intention, but I think many read it as invalidating of abstinence as an important endpoint and understanding relapse as, not just a disappointing setback, but a serious safety event without any guarantee of restabilization.

I believe the fuzziness around the conceptual boundaries of recovery intensifies conflict around these issues. There was a time when I welcomed researchers and academics focusing recovery. My friend Brian Coon has argued that “recovery” ought to be left to mutual aid groups and proposed that professionals focus on “stages of healing.” I’ve been coming around to the notion that we might be better off focusing on quality of life.

Closing

I fear this has been a meandering and repetitive post, so I’ll summarize here:

- It’s important to recognize and distinguish between the types of alcohol and other drug problems in research, treatment, and professional communication.

- It’s important to recognize that some endpoints (abstinence) aren’t necessary for some SUDs (mild to moderate), AND some endpoints (non-abstinent) will not be compatible with high quality of life for many with high severity SUDs (addiction).

- Further, we can affirm that it is not moralistic to recognize that, for a minority, abstinence is the only endpoint that will allow maximal functioning. (We can also acknowledge that this isn’t grounds for coercion.)

- We might do better to focus on quality of life, flourishing, stages of healing, etc. than on recovery, due to its increasingly fuzzy conceptual boundaries.

- Non-abstinent endpoints can serve multiple purposes that don’t have to, and shouldn’t, replace abstinence as the optimal endpoint for a minority of people with alcohol and other drug problems.