So far in this series I’ve…

In the previous post I mentioned that Tom, given his tendency toward a macro and outward-facing mindset, turned his thinking in the direction of system change.

In this post, my final one in the series, I will give an overview of how we incorporated system change and some related methods in our Recovery Alliance Initiative. And then I’ll share some concluding comments.

At this later stage in our collaboration, Tom turned our attention toward system change methodology and adding that to our work in the Alliance. So for this post, I’d like to introduce some potentially powerful ideas and practices that come from certain system change methods. These are-big picture ideas, but they also become quite specific – so the reader might find this information to be practical.

To start to consider system change more fully and specifically, the reader should consider exploring the resource Tom found. The “Collective Impact” model from Stanford University provides an insightful and practical framework. It guides us in how to go about a large change effort even at the level of a whole community (making sure you’re hitting all levels of possible change, and identifying specific elements to drive change, etc.). When Tom shared it with me, I was a bit astounded by it in a good way.

The Collective Impact model is far too large a topic to cover here but I encourage those that are interested or curious to check it out.

My response to Tom introducing me to the Collective Impact model was to begin to investigate system change on my own. I found a resource called “FSG: Reimagining Social Change”. Those materials include the question, “What is system change?” And their answer is that system change is about “shifting the conditions that hold a problem in place.”

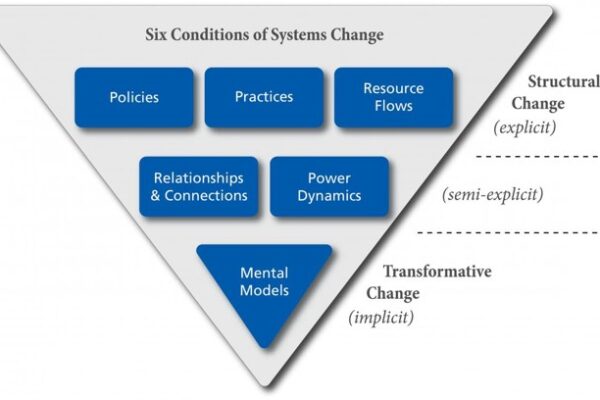

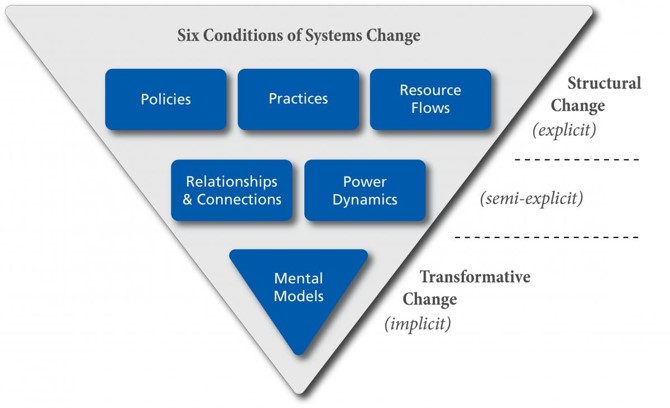

Having no background in social work, public health, or policy, I was amazed by this visual that they use.

They note that it is important to consider every one of those levels in a system change effort. For example,

- you might have all the resources lined up, and be ready in terms of policy and practices;

- and you might also have the relationships and hierarchical support that you need.

But if you haven’t addressed the ideas relevant to the change you are trying to lead, and haven’t addressed people’s basic assumptions about what is in place and what you are proposing, you might be up against a whole type of stuckness that you can’t quite figure out.

In addition to the routine considerations of various resources and top-down authority, has your plan also specifically addressed the way people think about both the problem and your proposed solutions?

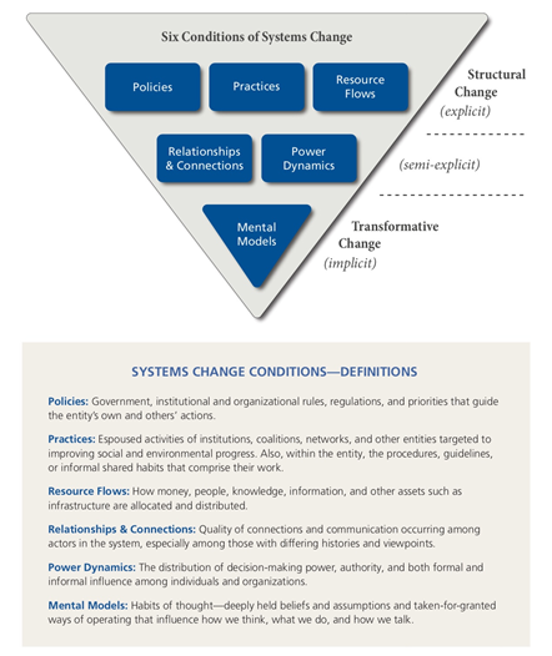

For those that might want a little more, here’s a bit of detailed language about each of these levels.

Over the years that Tom and I have conducted summit meetings, we have empowered and coached table leaders, as well as built project planning guides to help project leaders promote completion of change projects. But beyond that, we have noticed that eventually many people want to get even more practical. We have noticed that desire often arises in response to the mere process of the Summit meetings or the collaboration portion of our Alliance message – rather than to our content.

At this point you also might want to begin practical action of your own. You might be wondering what you can do right now.

In our meetings over the years, toward that end, we have suggested attendees consider a menu of possible practical actions, such as those listed below:

- Visit other sectors in your local area and get to know what each one does more specifically.

- Form a collaborative group to address a problem that coming to understand other sectors has revealed

- Become active in a collaborative work group that already exists.

- Collaborate on a project that addresses the local or county level.

- Look around your region and start to identify people, resources, and examples of collaborative work already done that would be helpful to real people in need in your local area.

- Help your own system to improve what it does or work together with other sectors in a better way, relative to Alliance concepts.

- Remember to take the long view in case coordination efforts for the person we serve, and not just the immediate or short-term view.

- Work on improving linkage with other systems by filling in the gaps of the lived experience of the people we are helping.

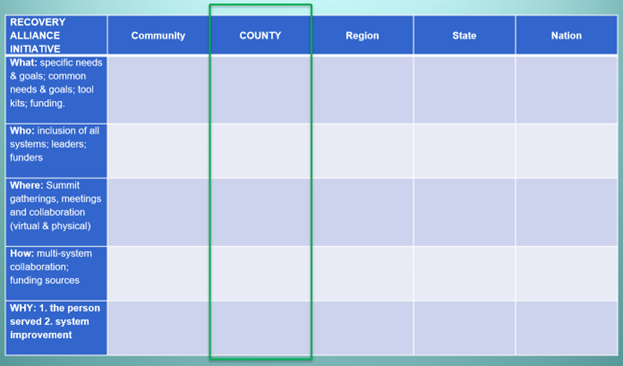

Further, I would like to provide you with one more item related to system change. Consider the grid below.

We often use this grid I made during our Summit meetings to help attendees see the big picture of Alliance potential and simultaneously narrow their focus at the level of the current meeting.

In the real example of the grid shown above, we were bringing the grid to a county-level meeting and formatted it accordingly. Within that example, consider the following that Tom or I would say to the attendees gathered from diverse sectors…

“To help you get focused today and moving toward action at the county level, consider this grid.

- At the county level, what common and specific needs and goals do you have?

- What kinds of tool kits or specific funding would be most helpful?

- What systems, leaders, and funders need to be included to move toward your county-level solutions?

- And to help get the work done, what collaborative working groups should be set up, and what meetings or gatherings are needed to support that work?

- Exactly what kind of multi-system collaboration do you think is needed to help the person we serve and to help our organizations improve what they do?”

Some Closing Comments

As I bring this series to an end, I’ll make some closing comments.

First, collaborative groups can meet in person or in videoconference. They can use the free Recovery Alliance Initiative website to message each other, upload documents, share documents and other resources with others, create a private group space for a project, and invite others into a project.

I’d also like to share what has become a favorite quote for Tom and me from one of our early and long-term Recovery Alliance Initiative supporters and Summit attendees, Terrence Walton. Terrence is the national head of all drug courts in the USA. At one of our meetings Terrence summed up the Alliance by saying that for him personally it was helpful to attend in order…

“…to know the field, to be known by the field, and to learn from the field, in order to change what needs to be changed, and improve what needs to be improved, if we are going to stay relevant, and to survive.

Lastly, I’d like to point out the latent tension found among the numerous differences between how Tom and I usually think. This tension has been a valuable source/resource.

Tom is an outward-facing macro thinker. By contrast, I’m an inward-facing thinker who is rooted in the one person we are attempting to help.

Tom often focuses on large numbers of people and teases me by saying something like, “But Brian, on the beach there are thousands of starfish. The one you throw into the water is just one.”

I’d like to say that as a clinician, I just can’t help it. To me, all our effort in the Alliance is for the sake of the one person we serve.

But in the Recovery Alliance Initiative, we focus on both.

This has proven to be fruitful. The collaboration between Tom and I (who are both quite different from each other in several important ways) has itself been a microcosm of the Alliance effort. And that difference and combination has flowed outward from the two of us. Combining our approaches has led to speaking invitations, interviews, consultations we have provided, etc., beyond what I have mentioned in this series – opportunities that his approach or my approach alone would not produce.

In closing I’ll simply say this series has been just a brief overview of a lot of effort over several years.

Below, find the references for this series as well as two suggested readings that relate to this work.

References

Boyle, M.G., White, W.L., Corrigan, P.W. & Loveland, D. L. (2001). Behavioral Health Recovery Management: A Statement of Principles.

Coon, B. (2015). Recovering Students Need Support As They Transition. Addiction Professional. 13(1): 22-26.

Crowe, K., Hennen, B. & Coon, B. March 31, 2017. A Seamless Transition: Linking College-Bound Emerging Adults with Collegiate Recovery Programs. Recovery Campus Newsletter.

DuPont, R.L., Compton, W.M., & McLellan, A.T. (2015). Five-Year Recovery: A new standard for assessing effectiveness of substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 58:1-5.

DuPont, RL & Humphreys, K (2011). A New Paradigm for Long-Term Recovery. Substance Abuse. 32:1, 1-6.

Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2011). Collective Impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9(1), 36–41.

Kloos, B., Hill, J., Thomas, E., Wandersman, A. & Elias, M. J. (2012). Community Psychology: Linking Individuals and Communities. Cengage Learning.

Osher, F.C. & Kofoe, L.L. (1989). Treatment of Patients with Psychiatric and Psychoactive Substance Abuse Disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 40(10):1025-1030.

White W, Boyle M, Loveland D. (2003). Addiction as Chronic Disease: From rhetoric to clinical application. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 3:107-30.

Recommended Reading

Goodheart, C. D. & Lansing, M. H. (1997). Treating People with Chronic Disease: A Psychological Guide. American Psychological Association: DC.

Kelly, J. F & White, W. (Eds.). (2010). Addiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research and Practice. Humana Press. (2010).