This post shares a few loosely connected tabs that have been open in my browser for a couple weeks.

An advocate’s sad end

Over the years, I’ve expressed concern about peer supports being placed in high risk situations with inadequate training, supervision, and support. My concern has grown as the OD crisis has accelerated, along with the use of peer supports on the frontlines of this crisis.

My concern has typically centered on people in the first months and years of their recovery being placed in environments and relationships involving regular exposure to drugs, cultures of addiction, trauma, etc. Peers are often the addiction professionals with the least training, supervision, structure, and institutional support. Because the onramp to being a peer is short, they are also often in early recovery.

Stories like Jesse Harvey’s are the kind I had in mind. It sounds like Jesse ran some recovery homes that, at first glance, look like decent programs. It was his harm reduction work–The Church of Safe Injection–that got him some national attention.

Of course, workers in recovery-oriented treatment settings sometimes relapse and OD too, but there are expectations of internal and external structures to support, guide, and protect workers.

From afar, Jesse Harvey’s work was interesting to me because he seemed legitimately inhabit both worlds–recovery and harm reduction. (I’m aware that many see no need to distinguish between the two.) It is sad to see his story end this way.

For me, it’s been important to distinguish between harm reduction as an approach to working with and engaging people who use drugs and harm reduction as a philosophy. I wonder if that distinction can serve as a protective factor for people in recovery. I don’t know, just a thought.

‘Peer’ work as precarious

A paper entitled ‘Peer’ work as precarious recently caught my attention. I imagined it was about the risks peers in recovery (recovery coaches) might encounter.

I was mistaken. It’s about the experiences of peers who currently use drugs.

They interviewed 15 peers who use drugs and work in harm reduction services.

One might imagine that people-who-use-drugs who are hired, as people-who-use-drugs, to help other people-who-use-drugs, would find that experience validating. This isn’t the case for the subjects of this paper.

Instead, the paper described the subjects’ reports of feeling exploited. This is one of the four themes explored:

Peer workers lacked access to workers’ rights and were unaware of what their rights included. Nonstandard arrangements systematically constrained access to rights as there was no formal employee-employer contract. Some said: “there’s no rights” ; and “[peers] have no rights”. These perceptions were concerning but reinforced by the numerous violations to provincial workers’ rights reported by participants, including wages that were below provincial minimums, a lack of social benefits (i.e. sick and vacation pay), physical and verbal intimidation, and no access to safety standards. Another participant shared a unique perspective on the lack of access to workers’ rights: that they were a PWUD.

“There’s also the question of drug use at work and how that impacts people and that’s one of the reasons why people get paid so less or much less…. if people are using drugs at work it’s, like, okay, fine, you can use drugs. But you’re not going to have any workers’ rights or be paid a basic wage type of thing.“

Negating workers’ rights was seen as necessary in a work culture that tolerated PWUDs substance use needs. This quote underscores the structural vulnerability of PWUD produced from the criminalization of drug use – even in harm reduction work.

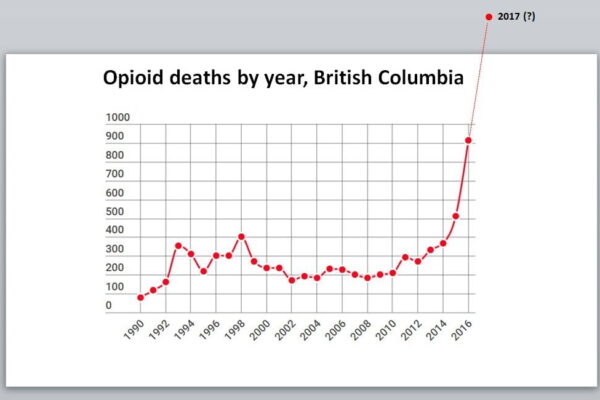

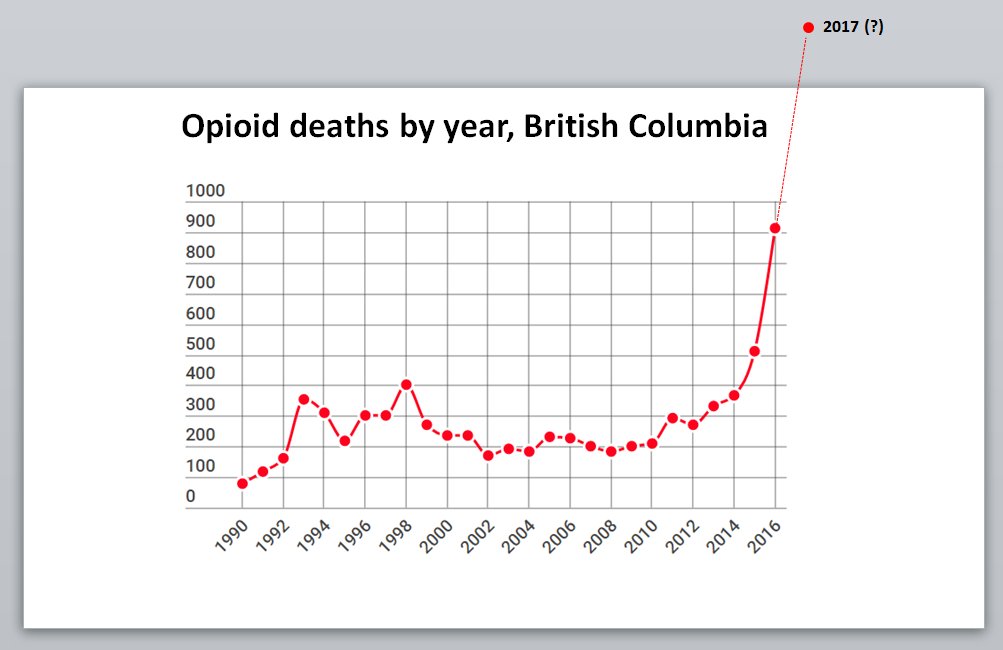

Model for drug policy?

British Columbia (BC) and Vancouver have been touted for having model drug policies for 2 decades. This blog has followed their drug policy for most of that time.

BC and Vancouver are at the vanguard of harm reduction policies and the experiment does not appear to be the success that many hoped for.

From CBC:

British Columbia has nearly matched its monthly record for deadly illicit drug overdoses, with 175 deaths during the month of July.

The BC Coroners Service saw 177 fatalities in June, which surpassed the previous high of 174 deaths in May. The service initially reported 175 deaths for June but updated the number on Tuesday.

A statement said the service has detected “a sustained increase” of illicit drug toxicity deaths since the first peak of the pandemic in March, and it’s now confirming five straight months with more than 100 such deaths.

The proposed solution? More harm reduction:

Medical leaders, physicians and advocates speaking Tuesday all called for the same measures to save lives. They pushed for decriminalization, a safe supply for users and erasure of the stigma surrounding substance use.

“Given the toxicity of the drug supply, now is the time for all of us to demonstrate compassion and empathy,” said Lapointe.

Communities that haven’t embraced harm reduction are struggling too and there’s no doubt that the pandemic has interfered with access to both harm reduction and treatment services, but it’s clearly not just the pandemic.

See: Overdose crisis? Or, addiction crisis?

See: Overdose crisis? Or, addiction crisis?

To me, the problem isn’t the interventions being used. It’s the absence of attention to treatment and recovery. The words “treatment” and “recovery” appear zero times in that article. There isn’t even mention of opioid agonists, just access to a safe supply of drugs.

This is where I get uncomfortable with harm reduction as a philosophy rather than a set of strategies/interventions. Harm reduction isn’t enough. (Treatment also isn’t enough. Too many people will die or get a chronic illness before achieving stable recovery.)

Seeing this through the philosophy of harm reduction leads people to framing this as a problem of toxic supplies and people using alone, rather than seeing it as an addiction crisis and seeking ways to better treat that illness–as though we’d want that life for a loved one… if only they had a safe supply and a using buddy.