Programs closing

This story about the impact of COVID on the treatment industry grabbed my attention:

At the beginning of 2020, addiction treatment was a solid, growing industry, with 15,000 providers, $42 billion yearly revenue, and a projected 5.2% annual growth. Then Covid-19 hit.

By the summer, the industry had lost $4 billion in revenue, and about 1,000 providers—and that’s just the beginning. According to the latest survey of the industry, published Sept. 9 by the National Council for Behavioral Health (NCBH), which represents about 3,000 mental health and addiction treatment providers, 54% of organizations have closed programs and 65% have had to turn away patients. As a result, nearly half have decreased work hours for staff, and over a quarter had to lay off employees.

My first reaction was ambivalence–there are a lot of bad actors and profiteers in the industry, maybe this will push some of them out.

Not so fast.

While a majority of rehabs have been hit hard, there is a specific group that is already seeing the effects of increased demand: High-end services. These programs have luxurious settings and amenities, and fewer patients, which makes it easier to prevent possible exposure to Covid-19. “We provide premium services, and that’s been the saving grace in this,” says Tieman.

His organization’s three premium programs—two in Pennsylvania, and one in Florida—have stayed at capacity through the pandemic, he says, because patients with the financial wherewithal to check into a premium residential treatment programs have continued to do so as they face a greater risk of substance abuse. Compared to the general programs, which costs $35,000 per month and is typically paid for with a combination of insurance and financial aid, the premium programs are $75,000 a month, with no discount offered, and though they have fewer patients, the programs have been helping the organization minimize the losses through the crisis.

Worse yet:

Many smaller providers have struggled to keep their businesses going, and in some cases, have shut down entirely. This is especially true for facilities funded primarily through public insurance, which have a harder time getting sustainable reimbursement rates and were already in the most tenuous shape prior to the pandemic. These are providers that tend to serve the most financially vulnerable.

While these programs get a lot of attention for quality issues, many of them do provide quality services and function as important safety nets for our most vulnerable community members.

Growth sectors

While we witness the demise of some portions of the industry, there have been changes to increase access to other types of care–primarily telehealth and buprenorphine prescribing.

Godinez’s process was almost impossibly simple: She texted her doctor and a drug counselor, who briefly evaluated her via FaceTime and wrote a prescription that she filled at a Walgreens around the corner from her Hendersonville, Tenn., home — a process that, until March, would have been largely illegal.

…

Now, as they wield unprecedented freedom to prescribe addiction drugs by telemedicine and evaluate patients by phone, many doctors and advocates say they’re unwilling to relinquish that flexibility without a fight. Already, there is a burgeoning movement to keep many of the new policies in place permanently. Many treatment providers across the U.S. have said publicly that the new status quo represents long-sought change that could positively transform patient care for decades to come.

“You can’t put the genie back in the bottle,” said Stephen Loyd, a Tennessee addiction doctor who treated Godinez and who once served as the state’s drug czar. “This is how it needs to be — always.”

The pandemic is also amplifying calls to eliminate the “X waiver” that requires physicians to receive 8 hours of training before prescribing buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorders.

Due to the COVID-19 emergency, the US federal government has temporarily waived the initial in-person assessment for initiation of buprenorphine and has increased flexibility for the dispensation of take-home methadone. These changes allow prescribers to initiate buprenorphine treatment remotely. These changes are welcome, and the federal government should do more along these lines. All providers with prescriptive authority should be allowed to prescribe buprenorphine, which could be achieved by removal of the requirement for a US Drug Enforcement Administration ‘X’ waiver. Emergency funding for buprenorphine and methadone should be released so that patients who are unable to afford these treatments, particularly in states without Medicaid expansion, can access treatment. Importantly, the structure of treatment settings themselves could increase infectious spread without thoughtful redesign. Limiting requirements for frequent in-person visits, facilitating remote healthcare delivery and providing these healthcare providers with appropriate protective equipment would be paramount to preventing the further spread of SARS-CoV-2.

The regulatory context

Meanwhile, I was talking with a friend who works for an FQHC (Federally Qualified Health Center) about their substance use disorder services. They have a fairly robust MOUD service, prescribing a lot of buprenorphine and some extended-release naltrexone.

I asked about other services for addiction. He reported that they are unable to provide addiction treatment because they are not licensed for it.

Let that sink in.

The hurdle for prescribing buprenorphine is an 8 hour training for the prescriber (24 hours for nurse practitioners and physician assistants). For outpatient group and individual counseling, it’s licensure as a specialty program.

Further, we’re seeing the implementation of higher regulatory standards for addiction treatment. This is in response to quality problems in many programs. It’s not a bad thing, if done properly.

So, we got a push for the deregulation of medications for opioid use disorders (MOUD) and a push for increased regulation of other forms of treatment.

Should we care?

As this blog has pointed out over the years, diversion of buprenorphine is a reality.

Most advocates quickly respond that illicit use of buprenorphine is for non-medical self-treatment and avoidance of withdrawal by people with opioid addictions. Further, that this is proof that buprenorphine is over-regulated.

A recent story in Filter explores the emergence of buprenorphine misuse by people who were not previously or currently using other opioids.

There has been an abundant market for Suboxone on the streets of Kensington for several years, as I’ve reported for Filter. And some municipalities, including Philadelphia, have begun dropping criminal penalties for possession without a prescription. But until recently, I had never met a Suboxone user who didn’t previously or concurrently take another opioid.

...

The reasons for its emergence are complex, but a significant factor is the ease with which Suboxone, thanks particularly to its sublingual film form, is smuggled into jails and prisons—and then concealed and divided once inside. Together with synthetic cannabinoids (called “deuce” on Philly street corners), Suboxone is anecdotally the favorite drug in Philadelphia County’s carceral settings.

…

Once inside, the strips are cut into smaller pieces which are taken orally, or else dissolved in water and snorted. The euphoric effects of buprenorphine on a person without opioid tolerance are indistinguishable from other prescription opioids. Regular use can lead to physical dependency. So released people, as they have recently described to me, have been returning to the streets with a taste for the orange films, which are sold up and down Kensington Avenue and on street corners across Philadelphia.

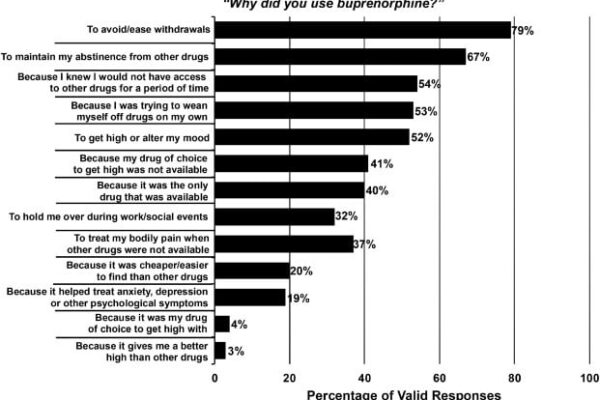

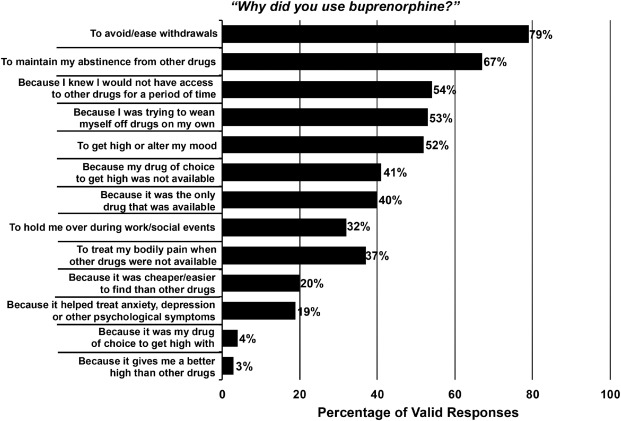

A more scholarly look at non-prescription use of buprenorphine found that the most commonly cited reasons for non-prescription use were self-treatment and avoiding withdrawal. However, more than half (52%) of respondents reported using it to get high.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Chilcoat HD. Understanding the use of diverted buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Dec 1;193:117-123.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Chilcoat HD. Understanding the use of diverted buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Dec 1;193:117-123.

While it hasn’t been widely reported, this has been known for years. My first post on the problem was in 2006. Further, failure to acknowledge the problem has the potential to create serious barriers for many people with addiction seeking recovery. For example, mandates that all recovery homes allow opioid agonists like buprenorphine. (Those SAMHSA guidelines were not mandates, but mandates have been discussed at the state and regional levels. The first step is making funding of services contingent on integrating opioid agonists into all housing programs.)

What we miss when we focus on opioid treatment and recovery

(This section is a post from September 17th, 2019)

Fortunately, there’s been growing concern that advocates, policy makers, and media have to narrowly focused on the opioid crisis. Up to this point, it hasn’t reached the level of media coverage.

USA Today is one of the first to publish an article that explores the limitations of the nation’s focus on opioid treatment and recovery:

More than eight years into his opioid-addiction treatment, Paul Moore was shooting cocaine into his arms and legs up to 20 times a day so he could “feel something.”

The buprenorphine he took to quell cravings for opioids couldn’t satisfy his need to get high. Moore said he treated himself like a “garbage can,” ingesting any drug and drink he could get, but soon enough, alcohol and weed had almost no effect unless he vaped the highest-THC medical marijuana available.

Cocaine, however, especially if it was mainlined — now that could jolt him from his lifelong depression to euphoria.

The article provides several important messages:

- The importance of addiction treatment over opioid use disorder treatment for many (if not most) patients.

- Along similar lines, messages about opioid recovery can be misleading for patients, families, and communities.

- These issues raise the importance of clarity about the boundaries of recovery. For example, were these people in recovery when they were in opioid use disorder treatment and reduced or quit using opioids, but were still using cocaine and experiencing poor quality of life due to untreated addiction? (This would have been an uncontroversial and easy question to answer just a few years ago. Today, there are many saying that any movement toward wellness or participation in harm reduction is recovery.)

- The article also highlights what gets missed when agonist treatments (buprenorphine and methadone) are described as the most highly effective and highly successful treatments without more context. They rarely answer the question, effective at what? (This isn’t saying that these medications aren’t useful or don’t have a place in care. Rather, it’s important that journalists and experts do not oversell their evidence for effectiveness.)

Failure to clarify and communicate these messages are likely to result in increased stigma for addiction and recovery.

Rather than communicating that addiction is a treatable illness, the unintended message will be that addiction more closely resembles a chronic disability than a treatable illness that has a good prognosis when the patient receives treatment of adequate quality, duration, and intensity.

This century’s first wave of recovery advocacy was built upon the message that we can and do recover when we get the right help and support. In this context, recovery meant something resembling the Betty Ford Consensus Panel definition:

Recovery from substance dependence is a voluntarily maintained lifestyle characterized by sobriety, personal health, and citizenship.

The traditional understanding of addiction recovery alludes to the restoration of people in their families, communities, and to a life in alignment with their goals and values.

Adjustments to that understanding are likely to result in readjustments in the public’s attitudes, which are eventually likely to result in readjustments in policy.