JAMA published new research on buprenorphine initiation and retention and the findings are disappointing.

The study looked at a database of retail pharmacy records from 2016 to 2022 that includes 92% of all retail pharmacies. (93, 713, 163 prescriptions)

If I understand correctly, this excludes buprenorphine dispensed in emergency settings. Those patients would only be included if they followed up and filled a prescription at a pharmacy. Medication dispensed in emergency settings is usually limited to a few days and would presumably have the lowest retention rates. The exclusion of those emergency prescriptions should tell us only about people who took the steps of going to a pharmacy and filling a prescription.

Initiating buprenorphine was defined as a prescription for a patient without a filled buprenorphine prescription in the last 180 days.

Retention was defined as continuous buprenorphine prescriptions filled over 180 days without any gaps of more than 7 days.

What did they find? [emphasis mine]

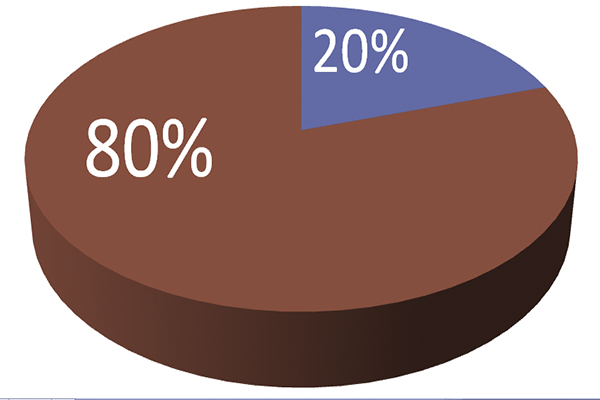

During January 2016 through October 2022, the monthly buprenorphine initiation rate increased, then flattened. This flattening occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting that factors other than the pandemic were involved. Throughout the study period, including in 2021-2022, only 1 in 5 patients who initiated buprenorphine were retained in therapy for at least 180 days, a rate similar to that found in a prior study examining data through the end of 2020.4,5

Chua K, Nguyen TD, Zhang J, Conti RM, Lagisetty P, Bohnert AS. Trends in Buprenorphine Initiation and Retention in the United States, 2016-2022. JAMA. 2023;329(16):1402–1404. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.1207

The stalled initiation rates are disappointing in the context of massive federal, state, and local efforts to increase buprenorphine treatment.

How do the authors explain these findings? [emphasis mine]

These findings suggest that recent clinical and policy efforts to increase buprenorphine use have been insufficient to meet the need for this medication. A comprehensive approach is needed to eliminate barriers to buprenorphine initiation and retention, such as stigma and uneven access to prescribers.

Chua K, Nguyen TD, Zhang J, Conti RM, Lagisetty P, Bohnert AS. Trends in Buprenorphine Initiation and Retention in the United States, 2016-2022. JAMA. 2023;329(16):1402–1404. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.1207

Other Explanations

I don’t doubt that stigma and barriers to access to prescribers play a role in these findings, but I imagine there are more important factors at play. After all, these were patients who received, accepted, and filled a prescription–they found a prescriber and stigma didn’t prevent them from starting treatment.

Is it possible the treatment isn’t delivering the outcomes these patients need or want? (It’s important to note that this could mean a lot of things. Some related to the medication, some not.)

For example, we know that polysubstance problems are the norm among people seeing treatment for opioid problems. If a patient presents with opioid use disorder, alcohol use disorder, stimulant use disorder, and cannabis use disorder, do they have 4 disorders? Or, do they have one disorder–addiction? If they have addiction, and we only treat opioid use, how successful is that likely to be? For someone with addiction, is “opioid recovery” an appropriate clinical endpoint?

For those patients with addiction, it is a uniquely complex bio-psycho-social-spiritual illness. Does the treatment these patients were provided address these complex and intersecting needs? Or, did it just target one of the biological factors?

Further along these lines, these findings may point to tensions in poorly developed and poorly aligned clinical, community, and individual models for recovery and wellness. Bill White explored this in a 2012 speech:

…historically the mental health field has had a very well-defined definition of partial recovery but literally no definition, until very recently, a full recovery from severe mental illness. We now have long-term studies of the course and trajectory of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, for example, that are really challenging that, and really beginning to signal the emergence of the concept of full recovery from some of the most severe complex psychiatric disorders.

On the addiction side, in contrast, we’ve had a very well-defined—a reified, if you will—concept of full recovery and no concept of partial recovery. In fact, it’s almost heresy to even begin to talk about a legitimized concept of partial recovery within the addictions field.

There’s a third concept within this framework that Ernie Kurtz and I ran into. We began to find scientific evidence in lots of anecdotal reports from therapists about people who got better than well. What I mean by better than well is that these are not people that we simply extracted the pathology out of their lives, but these are people who, not only went on to recover, but they went on to live incredibly rich lives, in terms of the quality of their life and service to their communities, and these are people who would later begin to talk about addiction and recovery was for them a blessing.

Experiencing Recovery, 2012 Norman E. Zinberg Memorial Lecture, William L. White

This “better than well” concept fits nicely with emerging models of post-traumatic growth.

In the context of the overdose crisis, more than ever, we need legitimized models and pathways for each to reduce harm, improve QoL, and achieve stable recovery for the greatest number of people. And, we need to avoid pitting them against each other.

Acknowledged or not, we have systems, resources, communities, and providers based on particular models. It might help to acknowledge this and address it much more explicitly. I imagine we’ll be stuck as long as we continue to have providers and systems that delegitimize and disavow responsibility for these pathways. This doesn’t mean providers need to be all things to all people, but validation and coordination would go a long way.