Why consider the change process, and what is the application of the ideas I will present?

- Clinical addiction professionals are trained in sequential change (Stages of Change, 12 Steps, etc.) rather than continuously wholistic, organic and dynamic change processes.

- Should we always assume and work within a staged approach?

- Clinical addiction professionals are trained in symptom reduction (drug use, craving management, managing triggers, drug refusal, etc.) and personal goal attainment (gaining employment, entering school, etc.).

- Should we only work in logical steps toward attainment of concrete goals?

- Clinical addiction professionals are trained in interviewing strategies that are targeted to bring about clinically-derived outcomes, goals, and changes.

- Should we overly-rely on questions, reflections and paraphrasing meant to bring about changes chosen by the counselor?

Could it be helpful to adopt a holistically-centered method with some individuals, rather than a method centered within fixed stages, concrete steps, and questions moving toward the counselor’s goals?

A 3-sided continuous process

In recent years I became interested in experiential and phenomenological topics. For me it was time for a change. My academic training in the 1980’s was rooted in models far from the experiential and phenomenological:

- radical behaviorism

- clinical behavior therapy

- cognitive therapy

- behavioral learning models of addiction (e.g. based on Pavlovian conditioning),

- and behavior modification methods for substance problems (e.g. controlled drinking).

And I had a resulting and rather limited range of clinical experiences over a fairly long period of time.

Exploring other sources, I found a body of academic and clinical research literature that was quite different, and focused on:

- themes and patterns of change

- dynamic change processes

- synergistic processes

- tension-release, both within a person and between a person and society, and

- critical thresholds that evoke change processes and movement.

Given my background in linear models (e.g. behaviorism, cognitive-behavioral psychology) and the length of time devoted to using my original training toward rather rigorous fidelity, I was ready for something new.

In this newer learning, I was especially intrigued by one article (Jorquez, 1983) in particular, because of two key factors related to change processes that were highlighted in that paper: extrication and accommodation.

- One factor Jorquez described as critical in the change process was extrication from addiction illness and the related context and lifestyle. Being extricated from the rubble of the past made sense to me. The idea of extrication seemed natural based on my clinical experience, and additional thoughts about change I was formulating.

- Jorquez identified a second key factor in the change process: accommodation of the new. After further reading on dynamic change, I found that the basic idea of accommodation is central to change overall. And it turned out that accommodation was natural for me to consider after all, given my academic familiarity with cognitive schema and social psychology.

After considering “extrication” and “accommodation”, I took the liberty of adding “shedding” to the ideas presented by Jorquez. I meant for “shedding” to hint at things like releasing and renouncing, especially as one moves through life seasons, and reconsiders life layers.

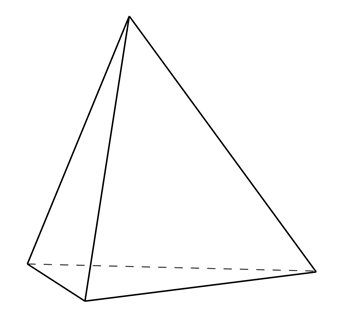

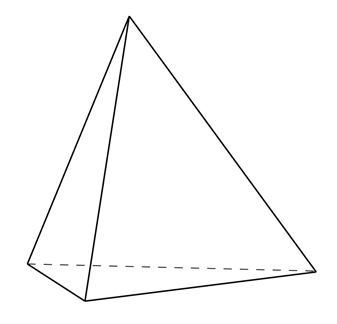

A Visual Diagram

I decided to represent the change process that happens during clinical work, as I had it in mind, with a four-sided gem (3 sides and a base).

Artwork: B. Schlosser

Artwork: B. Schlosser

The top 3 sides of the gem (as adapted from Jorquez) were:

- Extrication (from)

- Shedding (the old)

- Accommodation (the new)

And in my way of thinking about this, the top three sides rotate, shift, or move together. Or they are at least dynamically enacted concurrently in the moment (non-linear; see Resnicow & Page, 2008).

For me that made intuitive sense. And it fit over three decades of my clinical observations and two resulting conclusions:

- People often do not change in a linear or predictably-ordered fashion;

- People often do the work of multiple sub-processes of change (like extrication, accommodation, and shedding) simultaneously, over long periods of time1.

But what was the base of the object going to signify?

The base, or bottom, of the change process as I wanted to represent it would be the environment brought about by the clinician.

I was introduced to some articles related to the general idea of the therapeutic environment later in my career, and they hit me particularly hard – in a good way. So, my idea was of a very particular kind of clinical environment.

One article (Bion, 1967) discussed specific aspects of clinician memory and desire. The article described how a clinician could endeavor to have no memory of the patient or past sessions with the patient, intrude into the current moment. And it also described how the clinician could endeavor to have no clinically-imposed desire for the patient’s future over-ride the current moment.

- “No memory” of the patient was hard for me to accept. But the idea in the article was for the clinician to ask themselves if they are meeting with the person, or merely with their memory of the person? The point of the challenge was to direct one’s attention wholly to the person that is with the counselor in the now, rather than the remembered version of the same person as they were in previous meetings. That kind of push for deep empathic attunement held a lot of appeal to me.

I quickly added one more feature of the clinical space I was building: “no time”.

- That might sound strange. I’ll put it like this: since starting clinical work in 1988 I have never had a clock in my office. Why is that? When the patient sits down, I endeavor for time and the keeping track of time to go away. (Admittedly, working in residential settings my whole career and long-term residential for 19 of those years fed that freedom).

I also wanted “no question asking” to be included.

- During the Behavioral Health Recovery Management (BHRM) project our leadership team decided that the Achille’s Heel of addiction counseling is the over-reliance on asking questions. Across our entire agency at that time, we endeavored to mindfully eliminate as much question asking as possible, even while conducting assessments.

Thus, in my thinking on clinical environment, “no question answering” would also be a natural stretch-goal, in keeping with basic person-centered and motivational-enhancement methods.

Lastly, given my other recent reading in philosophy, I decided demands in science, philosophical assumptions, and forced applications of clinical art were all subject to “go away”.

Expanding on Bion with my additions, I developed my personal definition of what is otherwise called “the analytic stance”. And I decided to use my formulation of the analytic stance as the base:

- No time

- No art

- No science

- No philosophy

- No question asking

- No question answering

- No memory

- No desire

Adapted from: Bion, W. (1967)

A challenge

When I introduced my formulation of the analytic stance to a workplace colleague, and explained its use in this context, I was challenged to replace it with the therapeutic “common factors” (as they are called in clinical parlance). But I declined. Why did I decline?

I knew all too well from my relatively rigid fidelity-based past that the common factors of warmth, attunement, pacing and other behaviors that can be reliably observed and scored by trained 3rd party (rating) clinicians can be feigned while fidelity is met.

Using the “common factors” was not enough.

For my newer formulation of the change process the “analytic stance” as I defined it is my preferred operational mode. Why? To me it holds both the interior (less observable) and exterior (more observable) aspects of the whole person of the therapist with more validity related to purpose, compared to techniques that are easier to replicate or feign, are pre-packaged, and perhaps more shallow.

Looking back

This later-career self-study consisted of many articles concerning multiple models of recovery from addiction illness, 12 step facilitation as a clinical practice, the mechanisms of change in 12 step recovery (in both the treated population, and untreated population), and the history and development of the concept of addiction recovery as it applies to clinical therapy and related research. And it led to additional readings. It turned out that in doing that reading I came across some remarkably interesting notions about how some change happens for some people. And those notions were not of the kind I was accustomed to.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Katherine Mace and to Jason Schwartz for their comments on earlier drafts of this blog.

References

Bion, W. (1967). Notes on Memory and Desire. The Psychoanalytic Forum. 2:272-273, 279-280.

Jorquez, J. (1983). The Retirement Phase of Heroin Using Careers. Journal of Drug Issues. 13:343-365.

Resnicow, K. & Page, S. E. (2008). Embracing Chaos and Complexity: A Quantum Change for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health. 98(8):1382-1389.

Suggested Reading

1 Here we have a research observation that people undergoing addiction treatment might be simultaneously brainstorming hoped-for possible selves to pursue, feared possible-selves to avoid, refining and narrowing those choices over time, and developing and revising related action strategies – all while roughly progressing through Stages of Change relative to their SUD. Dunkle, C., Kelts, D. & Coon, B. (2006). Possible Selves as Mechanisms of Change in Therapy, in C. Dunkle & J. Kerpelman (Eds.) Possible Selves: Theory, Research and Application. (pp. 186-204). Nova Publishers.

Marquis, A., Douthit, K. Z. & Elliot, A. J. (2011). Best Practices: A Critical Yet Inclusive Vision for the Counseling Profession. Journal of Counseling & Development. 89: 397-405.

Thomas, C. (2013). Ten Lessons in Theory: An Introduction to Theoretical Writing. Bloomsbury Academic: New York.

White, W. L. (2007). Addiction Recovery: Its Definition and Conceptual Boundaries. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 33: 229-241.