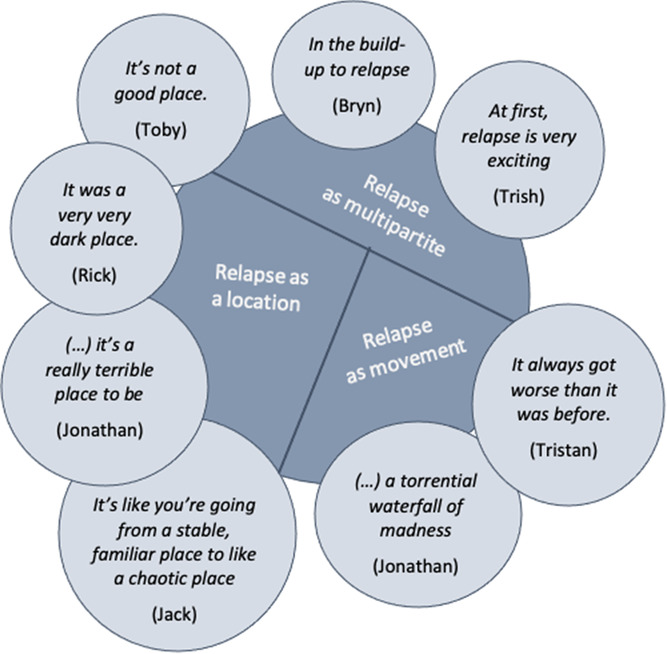

I recently listened to this interview with Maike Klein discussing her qualitative research on the experience of relapse in people with addiction who have experienced repeated relapses.

Here are a few take-aways:

- The experience of relapse is one of self-betrayal — one self being wholly committed to abstinence/recovery and a self at another point in time betraying that commitment.

- A demoralizing element is the loss of trust in self. Knowing that a future self will betray themselves. This is an experience of powerlessness.

- She distinguishes this from self-efficacy which she frames as confidence in oneself to navigate risk environments (external threats to their recovery). Self-mistrust frames the threat as oneself.

- She explored the impact of relapse on clinicians:

- She speaks to trauma associated with witnessing relapses and deaths associated with relapses.

- There is a parallel process between patients and therapists.

- Therapists develop their own experience of self-mistrust and begin to question their own knowledge, skills, and capacities. (They internalize the relapse — I’m not up to the task.)

- Therapists begin to distance themselves emotionally from clients and she describes and experience of clinician powerlessness and implies that the clinician begins to externalize the experience — this is what clients with addiction do… this is addiction.

- This results in emotionally distant therapists. (And, eventually, an emotionally distant system of care.)

- The therapeutic environment becomes untherapeutic.

Why this is noteworthy

We are in a moment where there is so much emphasis on the suffering in addiction as a product of external responses to addiction and relapse. Her work describes the internal consequences of relapse and drug use within addiction. External responses can influence that experience, ameliorating it or making it worse, but that internal suffering exists regardless of external responses.

Her exploration of the parallel process experienced by clinicians (intensified when deaths are experienced) powerfully describes the threats addiction professionals face to maintaining their own wellness, the challenges clinicians and systems face in trying to maintain a hopeful recovery-orientation, and the consequences when that parallel process is not addressed and managed.

Questions

- Is it possible that her description of that parallel process explains some of the current trends in drug policy discussions?

- If so, how does it show up?

- Is it likely that the overdose crisis makes us uniquely vulnerable to playing out that parallel process?

- Does the overdose crisis amplify the consequences of failing to acknowledge and manage parallel process?