In a compelling study from Dublin, Paula Mayock and Shane Butler (Trinity College) make the point that little is known about the stigma experienced by individuals attending drug treatment services over prolonged periods. They explored this through the lived-experience narratives of 25 people prescribed long-term methadone. Their findings ‘reveal the intersection of stigma with age as profoundly shaping methadone patients’ perspectives on their lives’.

I like qualitative research because it is often affecting – stories bring to vibrant life important things we need to consider. You remember stories. You remember the feelings they engender. I connect with qualitative research in a way I never can with tables, graphs and statistics. I connected emotionally with this study.

In this study, 16 men and 9 women were interviewed. Two thirds were over the age of 40 and 16 of them had been on methadone for 20 years or more. Two were now long-term abstinent from all drugs including methadone. Nine people were attending a clinic for daily supervised consumption. Only three of the 20 were employed full-time.

The findings of this paper did not make for an easy read. You can sense something beyond detached academic curiosity here. Butler and Mayock reflect:

An intensity permeated these narratives in the sense that interviewees frequently – and, at times, emotionally – recounted treatment-specific experiences that engendered a sense of ‘otherness’ and shame.

Mayock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 2021

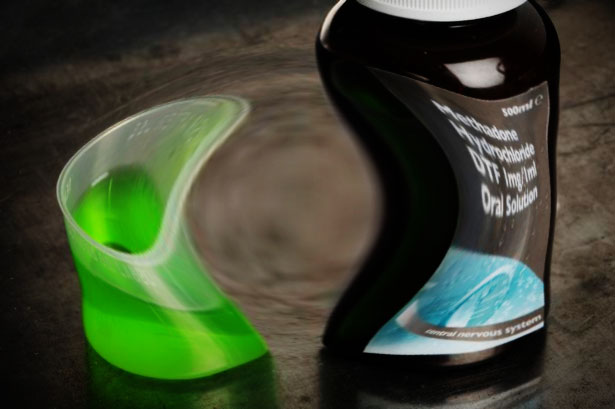

Methadone was seen as an instrument of punishment, ‘reflecting and amplifying’ public stereotypes around drug use and addiction:

It’s so demoralizing to go into the clinic and you’re just, you’re pissing [urinating] in bottles and grovelling to your doctor and grovelling to the chemists and that was your life, that was my life, you know.”

Rachel, service user

The research participants describe feeling ‘not normal’, having to ‘duck and dive’ and being treated ‘like dirt’. The absence of connection with the professionals they had contact with seems astonishing to me and the perception of being controlled or punished by the ‘techniques’ of treatment – e.g. threats of removal of takeaway doses for ‘dirty urines’ – was upsetting. Bad experiences reportedly extended to pharmacies where ‘public shaming’ took place.

The relationship with age and time on MMT (methadone maintenance treatment) was explored – there was a particular shame around being on methadone at an older age or for a longer period of time, such that individuals wanted to hide this, in a way that did not apply to other prescribed medications for other conditions.

The most harrowing theme in the paper is what Mayock and Butler call the private burden of stigma – the pernicious inner voices suffered by the participants, instilled powerfully and cemented down by years of reinforcement. The result is diminished spirit, low self-esteem and an erosion of humanity .

That’s what you do as a drug addict – you let people down, you’re unreliable, you’re of fucking no use to nobody.

Cormac, service user

The authors’ conclusion is hard hitting:

The lived experience of long- term MMT in Ireland is one characterized by relentless stigmatization, reflecting the marginal position of addiction treatment within the wider healthcare system and a failure to normalize methadone treatment.

Mayock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2021

It’s impossible not to have a strong reaction to this paper – it made me angry and sad and frustrated, but we do need to be a little careful here. The numbers are small, this is only one area of Ireland, and we are not hearing the other side of the story – how providers might see the situation and what limitations and duress they are working under, but that said, this is powerful stuff which merits consideration and further research.

So, what’s to be done?

The authors identify some issues specific to Ireland relating to the introduction of MMT which may be partly responsible, and they welcomed a policy shift away from criminal justice approaches towards a health approach, accepting that the tensions between the two are difficult to erase. They question the impact of a public campaign to tackle stigma, instead calling for organisational change in clinics and social structural change outside of treatment settings. Perhaps the most profound challenge they give us though is what we do with the upsetting legacy of what we’ve read in this paper.

I come back to a concern that bothers me here: the tension between what’s good for public health and what individuals want from treatment. The subjects in this research can’t have entered into treatment because they were seeking public health benefits from MMT – they would have wanted to see their lives getting better. The authors acknowledge this explicitly:

The well-documented public health benefits of MMT were not matched by a perceived improved quality of life among this study’s methadone patients

Mayock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2021

Mayock and Butler have looked at this in more depth in a separate paper (which I’m planning to come back to a different time) where people (the same ones I suspect) on MMT report being ‘passive recipients of a clinical regime that offered no opportunity to exercise agency’. This observation fits in with studies from elsewhere prompting the development of a large scale study looking into quality of life of those patients in treatment on MAT recently announced in the British Medical Journal.

While methadone and other examples of MAT have strongly evidenced benefits, medication does not offer meaningful healing for hurts. Methadone is not the problem here, nor is this only about stigmatisation. If we give methadone the blame we miss a trick.

I was struck by the absence of any focused interventions reported in the clinical settings where methadone was dispensed. Where was the compassionate approach to trauma? Where were the practical supports for housing, benefits, employment, families? Where were the mental and physical health interventions? Perhaps they were there but not reported, which says something in itself.

What would it have been like, I wonder, if the individuals had been offered significant support and interaction in each setting – primary care, clinic, pharmacy – by peers with lived experience? There is a call by the authors for involvement of stakeholder groups committed to harm reduction, but why not committed to harm reduction and recovery? Harm reduction is essential, but it’s not an end in itself. I have written recently about this quoting Eric Strain who talks about the importance of finding meaning and purpose and allowing people to ‘flourish’ in treatment.

So why not have peers on MAT, for instance, who had achieved their goals from treatment. Or peers who had moved on from MAT to abstinence? Or a mixture. What if clinics were perfused with hope and that hope was embodied in peer role models who had knowledge and experience of moving on and developing – of flourishing?

I have another concern. The word ‘recovery’ appears only twice in the text – once in a document title, and once as a point of tension where harm reduction approaches have to be defended from an attack by ‘the recovery model’. I might have picked this up wrongly, but the implication seems to be that recovery models are part of the problem, something I’ve also heard from some authorities here in Scotland.

The proposed solution – that stakeholders argue ‘overtly, explicitly and strongly for public support and acceptance of methadone as a legitimate and effective form of addiction treatment’ misses the point, in my view, that the prescription of methadone alone will never fulfil that goal, because it’s what goes alongside the prescription that brings positives into lives instead of simply reducing the harms.

I would argue that the introduction of recovery-oriented systems of care, (including medication-assisted recovery as an integrated component), rather than being a threat here, have the potential to transform the structures that have led to this degree of stigmatisation. The absence of hope in treatment systems is not only damaging to service users, but to those working in services. It’s easy to get burnt out. We need to set the bar high not just because we value those we work with, but because we also value ourselves.

I’ll leave you with something hopeful I quoted in a recent blog about stigma.

The most effective strategy for combating opioid use disorder stigma may be to avoid a rhetoric of hopelessness, and instead emphasize the recovery potential of affected individuals and communities.

Perry et al, Addiction, 2020

Continue the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

Paula Mayock & Shane Butler (2021): “I’m always hiding and ducking and diving”: the stigma of growing older on methadone, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, DOI: 10.1080/09687637.2021.1886253