Background

David McCartney wrote a great post about the PHP model of care that addicted physicians receive and its outstanding outcomes.

David framed the PHP model as the gold standard treatment. I also frequently call PHPs the gold standard.

I recently shared an interview with Robert DuPont discussing his discovery that his methadone patients were dying of alcoholism. This prompted David to look more closely at the relationship between opioid use disorder and alcohol use disorder.

All of this raises questions about the nature of the problem and the target for the treatment. In the case of addictions, should we think about substance use problems as discrete disorders characterized by problems with a particular substance? For example, does someone addicted to alcohol, opioids, and cocaine have 3 disorders (AUD, OUD, CUD)? Or, do they have one disorder (drug addiction)?

Brian Coon responded with a great and provocative post asking whether it’s accurate to describe any current treatment as a gold standard.

In his post, Brian points out that advocates, researchers, physicians, and public health professionals often call opioid agonist treatments the gold standard for Opioid Use Disorder.

Brian wonders whether anything should be called the gold standard when the norm in addiction treatment is failure to adequately address smoking. He zeroes in one 2 big concerns about this failure. First, the illness and death caused by smoking. Second, can we say we’re effectively treating their addiction while we’re not adequately addressing their addiction to tobacco?

(Check these out for previous posts from David and Brian on tobacco/nicotine.)

Gold standard?

Should PHPs be called the gold standard? Let’s look at the definition.

The best or most successful diagnostic or therapeutic modality for a condition, against which new tests or results and protocols are compared.

McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine

This definition suggests that the designation is relative to other treatments, rather than an indication that it’s the best treatment possible, so use of the term seems appropriate.

The label has been applied to both PHPs and opioid agonists. Which should be called the gold standard?

Well . . . the definition has 2 parts: being the most successful treatment, and being the benchmark against which other treatments are compared.

Most successful treatment? – I’d say that PHPs could make the case for being the most successful treatment.

Benchmark? – In practice, it’s very clear that agonist treatments are the benchmark for opioid use disorders.

Availability? – Other definitions describe the gold standard as the “best available” treatment. The PHP model is not widely available, but agonists are.

Now, I don’t believe Brian was focused on technical application of the definition of gold standard. Rather, he was focused on our blind spot with smoking while more people die of tobacco related illness than from opioids or COVID-19.

The problem of tobacco

Tobacco and nicotine addiction has interested and confused me for as long as I’ve been interested in addiction.

The case for aggressive treatment of tobacco dependence among SUD treatment recipients is clear and compelling. Consider the following:

- It contributes to more illness and death than alcohol and all other drugs combined.

- Rates of tobacco use among addiction treatment seekers is more than 5 times the general population.

- People with other substance use problems have greater difficulty quitting tobacco.

- Most smokers in addiction treatment would like to quit.

- Quitting smoking during treatment is associated with better treatment outcomes.

- Research has identified tobacco related illness as the leading cause of death for people who had been treated for alcoholism.

Despite all of this, we’ve failed to impact tobacco use in ways that correspond with its threat to recovery and health. Why?

Further, when systems respond in ways that treat tobacco as a serious threat to health and recovery, it evokes intense resistance.

Nicotine addiction is weird

Why do we fail to impact tobacco use in ways that correspond with its threat to recovery and health?

There are some obvious potential explanations–indifference, denial, avoidance, etc. These all undoubtedly contain some truth. And, I think we treat tobacco differently because there are noteworthy ways in which it is different.

- Tobacco does not cause the kind of euphoria we associate with other addictive drugs.

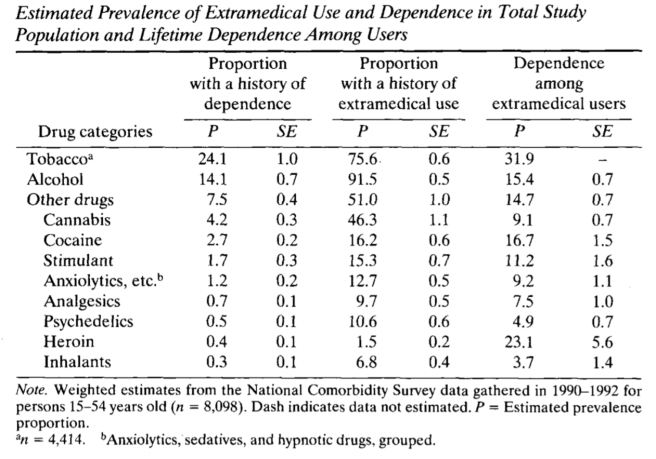

- Yet, it has a higher “capture rate” than cocaine, heroin, and alcohol. (capture rate = the % of users that will become chronic users of the substance)

- It isn’t associated with the kind of short term impairment in cognitive or motor function that we see with other substance use.

- It isn’t associated with the kind of role impairment we see in other addictions.

- Its most serious consequences are delayed by decades and have a very gradual onset.

- It’s a legal substance and, while use may be restricted in certain places, its use isn’t generally prohibited before or during work hours or while driving.

- Its legal status and its widespread use in the recovering community complicate efforts to simultaneously facilitate involvement in the recovering community and abstinence from tobacco.

- While there is growing empirical knowledge about the adverse effects of smoking on addiction treatment outcomes, this appears to be outside of the awareness of the user and those around them. Almost no one attributes their relapse to tobacco use.

- While there is growing empirical knowledge about the adverse effects of smoking on addiction treatment outcomes, the recovering community’s experience is people achieving decades of recovery while continuing to smoke.

- We’ve gotten millions of people to quit with tools like taxation and social control around where and when people can consume tobacco.

- I haven’t seen evidence that these people moved on to other substances.

- Strategies like taxation and social control seem inadequate to impact other drugs in the same way.

- People in recovery often report that the strategies that helped them stop using other drugs are not very helpful with tobacco.

What, exactly, do we really care about?

Much of Brian’s attention is on the deaths and illness associated with tobacco use. What if we were able to minimize deaths and illness? Would we still care? How much?

It’s not difficult to imagine a future where vaping completely replaces tobacco and is regulated in such a way that the risks to physical health are minimal.

I know a handful of people who quit smoking with nicotine gum and have never stopped using nicotine gum, continuing to use it for years.

Would we still question treatment that doesn’t center nicotine? Would we raise questions about the quality or completeness of individual recovery?

We also know that heavy caffeine consumption is common in the recovering community–enough to result in a withdrawal syndrome. Should we consider centering this in addiction treatment and recovery?

Wrapping up

I’m not, in any way, dismissing these concerns about our failures to address tobacco in treatment and communities of recovery. (I’ve preached about this for more than a decade.)

We’ve put a lot of energy into the argument that tobacco is no different from other drugs, but I think that part of the reason we’ve made so little progress is because nicotine is different in some important ways.

I wonder if exploring, identifying, and acknowledging the ways nicotine is weird and different will help us improve our efforts.