Ok… let’s talk.

A company called Ophelia Health has launched a new marketing campaign focusing on the message “F*CK REHAB”.

On the one hand, there’s A LOT to criticize in the addiction treatment world. At the provider level, there is a long history of really bad, predatory, poor quality, and abusive treatment springing from ineffective models, stigma, profiteering and exploitation. At the system level, we’ve never had real parity with care for other diseases, adequate funding, and cohesive systems of care.

Examples include tonic cures, cults (see also here), patient brokering, lobotomies, exorbitant lab fees, abusive teen programs, and cash-only office-based treatment. Some examples include treatment models or delivery methods that are inherently flawed and unethical, or ineffective under any circumstances. Other examples involve issues with quality, intensity, duration, or the integrity of the provider.

Bill White described 1980s treatment providers losing their way as they shifted from mission-oriented organizations to profit-oriented.

In the 1980s, addiction treatment programs shifted their identities from those of service agencies to those of businesses. A growing number of for-profit companies that measured success in terms of profits and quarterly dividends–rather than treatment outcomes–entered the field….

…Their self-images shifted from those of public servants to those of health-care entrepreneurs. For a time, a predatory mentality became so pervasive that it affected even some of the most service-oriented institutions. In this climate, alcoholics and addicts became less people in need of treatment more a crop to be harvested for their financial value. This evolving shift in in the character of the field left in its wake innumerable excesses that tarnished the public image of the field and set in motion a financial backlash that would lead to fundamental changes in the primary treatment modalities available to addicts and their families.

William White in Slaying the Dragon

I assume that Ophelia’s use of “rehab” refers to inpatient and residential programs, which dominated the industry in the 1980s. Over the last couple of decades, many residential programs have been among the worst offenders, with exorbitant rates, misleading marketing, inadequate duration of care, poor quality monitoring, and, in some cases, fraud. That there have been serious problems in residential programs does not mean that residential programs are universally problematic.

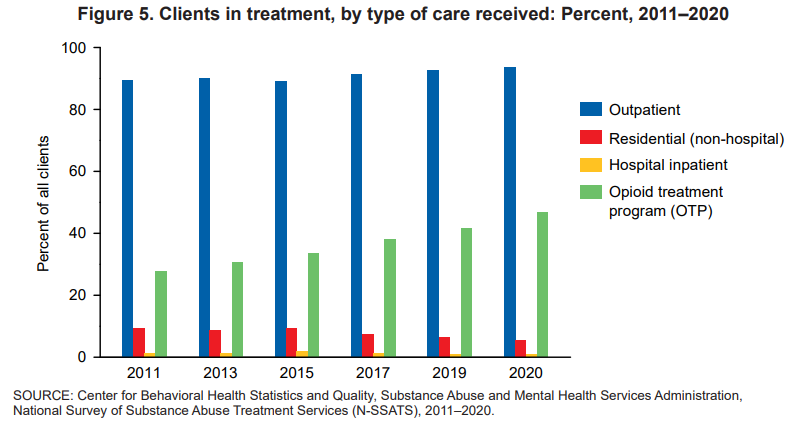

It’s important to note that residential and inpatient make up a relatively small and shrinking fraction of the treatment provided in the US today. (Note that this graph represents ALL clients, not just clients with opioid use disorders.)

Between 2011 and 2020, the proportions of clients in treatment for the major types of care—outpatient, residential (non-hospital), and hospital inpatient— shifted. Clients in outpatient treatment increased from 90 to 94 percent while clients in residential (non-hospital) treatment declined from 9 to 5 percent. The proportion of clients in inpatient hospital treatment ranged between 1 percent and 2 percent from 2011 to 2020

National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2020

I spent 25 years as part of a program that included outreach, outpatient, peer support, detox, residential, housing, and linkage to primary care that would help monitor recovery. We also took informed consent very seriously, with repeated discussions about the treatments we offered and didn’t offer and active linkage to treatments we didn’t provide. More recently, I spent 3 years as part of an inpatient unit that inducted a lot of high severity and high chronicity patients on agonist treatments. Programs like those — that provide rigorous informed consent and a continuum of long term care, or routinely initiate agonists — may represent a minority of inpatient and residential providers, but they were not alone.

Is “rehab” bad and telehealth good?

Ironically, digital behavioral health providers (Ophelia’s business category) have gotten some attention lately.

First, the Wall Street Journal reported on quality problems and prioritizing profits and the next round of venture capital over ethics and standards.

“When you put venture capital money into this mixture, it really pushes people to take risks,” Ms. Moore said. “It’s one thing to be a disruptive innovator, but there’s a reason medicine is encumbered by so many regulations — we’re dealing with people’s lives.”

Winkler, R. (2022, December 19). The failed promise of online mental-health treatment. via TheAustralian.com.au; The Oz.

A few months ago, a JAMA study was published and lauded as evidence for the effectiveness of MOUD (medication for opioid use disorder) treatment delivered via telehealth.

In a post about that study, I framed its findings as follows:

I want to make it clear that I harbor no skepticism about the importance of telehealth services as part of an effective system of care. With the explosion of telehealth during the pandemic, I’ve seen the benefits of telehealth in the engagement and retention of patients who might never try in-person services or stay engaged with in-person services for reasons as varied as transportation, scheduling, temperament, and medical or psychiatric comorbidities.

The study looked at medication retention and medically treated overdoses before and during the pandemic, with the before-pandemic group representing office-based care and the during-pandemic group representing telehealth care. They found good news and bad news.

The good news was that shifting to telehealth did not adversely impact either of these outcomes.

The bad news was that I found the outcomes to be very disappointing.

Retention rates for buprenorphine (defined as use over 80% of days) over 6 months were 31% for the office-based group and 33% for the telehealth group.

Retention rates for extended-release naltrexone (defined as use over 80% of days) over 6 months were 8% for the office-based group and 12% for the telehealth group.

18% of each group experienced a medically treated overdose during the study period.

The subjects were all Medicare patients. They had to meet age or disability requirements to enroll. However, the retention rate is not inconsistent with what I’ve seen in other studies with other populations.

I imagine most patients and families are looking for treatments that offer better than a 1 in 5 chance of an overdose, and 2 in 3 chance (or 9 in 10 for extended-release naltrexone) of discontinuing treatment within 6 months.

Are those outcomes explained to patients? Are they offered other options?

This criticism isn’t about the treatment being offered (in this case, medication) or the method of delivery (telehealth or in-person). My criticism is about the system of care that doesn’t offer treatment and recovery support of adequate duration, intensity, quality, and scope. (This is the norm whether you’re entering residential, outpatient, or office-based MOUD.) Further, it’s representative of an evidence-base that tends to speak only to outcomes like medication retention and overdose.

Treatment as usual isn’t cutting it (same for research as usual)

Ophelia’s “F*CK REHAB” evidence

Ophelia offers limited evidence for their marketing campaign. The screen capture above provides 2 bullets that speak directly to “rehab.”

- The first states that 2/3 of “rehabs” don’t prescribe medication.

- The second reports that “Once released from rehab, 90% of people who do not receive medication relapse within 3 months.”

Both points cite the same source: Bailey, G. L., Herman, D. S., & Stein, M. D. (2013). Perceived relapse risk and desire for medication assisted treatment among persons seeking inpatient opiate detoxification. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 45(3), 302–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.04.002

So, what does this article actually say?

The article is a strange choice to support this marketing message and their characterization of it is equally strange.

- It’s 10 years old, based on 12 year old surveys.

- I don’t see where it reports anything about the number of rehabs that prescribe or don’t prescribe medications.

- I don’t see where it reports 90% relapse rates within 3 months for people who don’t receive medication, but it does say that 90% of subjects reported relapsing within 12 months of their last detox episode. It doesn’t say whether they received medication in that previous detox experience.

- However, these subjects were current detox patients, therefore 100% of them have relapsed since their last detox episode.

- This study was done with patients currently in a detox program (average stay of 5.9 days) to evaluate their desire for MAT and to investigate the factors that influence this desire.

- This detox program provided methadone tapers, educated patients about MAT, and offered MAT to all patients. They asked about previous detox experiences to evaluate the influence of previous detox experiences on their perception of relapse risk and how that perceived risk influences their preferences for or against MAT.

- Even after a discussion of their relapse history and education about MAT, 37% of patients did not want medication.

- This was not a medication-naive group, many of them had previously received MAT: 43% methadone maintenance, 42% prescribed buprenorphine, and 6% Vivitrol.

So… the article doesn’t say what Ophelia said it said and it really doesn’t even seem to speak directly to their argument.

Ok. So, what about “rehab”?

They never really define rehab, but the study they direct us to focused on a 6 day detox program that tried to connect patients to ongoing care, including medications. (It’s worth noting that this was in 2011 and use of MAT has only increased in the years since.)

I think it’s fair to criticize many residential and inpatient programs, and the opioid crisis has increased the stakes for inadequate and shoddy treatment. I’d agree that detox that is not tied to long term care is unethical. I’d say the same thing about a 30 day destination programs that don’t include assertive long-term care.

However, the model with the best outcomes often includes residential treatment as part of the episode.

Further, our colleague David McCartney reviewed a recent Scottish report on residential rehab that found:

Rehab is linked to improvements in mental health, offending, social engagement, employment, reduction in substance use and abstinence. There is little research that compares rehab with other treatments delivered in the community, but where there is, the evidence suggests that “residential treatment produces more positive outcomes in relation to substance use than other treatment modalities.” The review also suggests that rehab can be more cost-effective over time than other treatments.

Where does this leave us?

The study Ophelia directs us to found a significant minority of patients do not want medication, despite considerable experience with medication among the subjects.

The JAMA evaluation of telehealth MOUD treatment found 67% dropped out by month 6, and 18% overdosed.

A Wall Street Journal investigation demonstrated that deficiencies in quality and ethics are a significant problem in digital behavioral health. (As has been the case in other treatment approaches.)

Years ago, having reached the conclusion that there is no silver bullet in addiction treatment, I came to believe that the only responsible systemic approach is to:

- offer a complete array of services;

- of adequate quality, intensity, and duration;

- by people who believe patients can achieve full sustained recovery (or flourishing);

- provide accurate information on their options (and the options not offered);

- let them choose the treatment approach that best fits their preferences and goals; and

- allow them to change their mind as they experience successes and setbacks, and their preferences and goals change.

I’ll leave you with a couple of thoughts from colleague David McCartney.

First, some of his thoughts on polarization in the field of addiction treatment and recovery support:

When those new to the addiction field question how unhealthy it seems, we all ought to sit up and take notice. We are responsible for the culture we have created. If that is a culture of conflict, we need to attend to it. Leaders have a particular responsibility here – we ought to be held to a high standard of behaviour and professionalism. That need not make us impotent, but rather be mindful of the power that we hold and how we use it. Change starts with ourselves.

There’s one more thing – another value – that is missing when there is turmoil. That value is humility. It’s not reasonable to expect that we all agree on everything all the time. This would be a disaster – we need to feel discomfort, disagreement and passion; these can be potent drivers for positive change, but perhaps a little bit of ‘I could be wrong and others right’ would go a long way to pour oil on troubled waters.

Polarisation, tension and hostility: just another day in the field of addictions.

Finally, from his post examining the effectiveness of residential rehab:

We don’t need to say one thing is better than another, but we do need choice and through shared decision making we can try to help patients align themselves to a treatment option that helps them meet their goals. And we need to be humble too. Evidence suggests that over a lifetime, most people resolve their problematic use of substances. When they look back, they may be grateful for the part that treatment played in their recovery, but it is likely that it will be only one of many factors that helped.

For the moment though, we can certainly challenge the voices that say ‘there’s no evidence that rehab works’, for there is ample evidence that it does. I’m not unrealistic about this though. As I’ve been writing, I have been mulling over the wisdom of Ahmed Kathrada’s observation: ‘the hardest thing to open is a closed mind’. That shouldn’t stop us trying.