As of July 1, SMART welcomed a new staff member to fill a brand-new position in the organization. Pete Rubinas became SMART’s first Organizational Culture Change Facilitator, representing a major internal effort to help SMART evolve in positive ways. Pete says, “As we attempt to be more inclusive of all, it’s critical that we have systems in place that support true inclusion. That’s what I’m focused on.” He also advises Acting Executive Director Christi Alicea and the Board on human resource, financial, and Board governance matters.

Pete came to SMART as a participant in January 2017 and, after training, became a meeting facilitator. In 2019 he added Regional Coordinator to the list of ways he is involved with SMART. He credits the program as instrumental in helping him build a balanced life without alcohol, “I also used the tools to change a variety of other problematic behaviors that were keeping me from being the whole human being that I wanted to be.”

Pete says the most rewarding part of what he does, so far, is amplifying the “voices” that need to be part of all the conversations at SMART. He credits his work running a Montessori school for ten years as something he can draw on in this regard.

Here are Pete’s responses to the Take 5 Spotlight questions:

- Are there tasks you perform regularly during your workday? No. When you are involved with change, every day is a new day! I spend a lot of time trying to understand the systems that exist in our organization, where the challenges are in those systems, and how we can work together to overcome them to truly shift our culture.

- What are a couple of the ways you interact and coordinate your job with national office staff? I always try to listen first, but I’m passionate about what I believe needs to happen to shift the culture, so I often have to rein myself in. I hope that my colleagues end up describing me as someone who listens well, says what he believes, and does what he says he’s going to do.

- What is one of the ways that you think you personally make/want to make a difference at SMART? I want to help build an open and positive culture that rejects white supremacy, sexism, ableism, paternalism, and all of the other -isms that get in the way of individuals feeling welcome in our spaces.

- What is your message to all those dedicated SMART volunteers across the country? Thank you for all that you do week in and week out for SMART Recovery. You are appreciated. And, if you ever doubt it, you are enough!

- What kinds of things are you interested in outside of work? Any hobbies? I am an avid birder, native pollinator gardener, and runner. I am also pursuing a Masters degree in Clinical Mental Health Counseling on a part-time basis. And my family, including four “kids” 18-21 years of age, is always my first priority.

For all the time Pete likes to spend outside, he is very aware of the internal work he feels called to do, “My mantra as an anti-racist White person is to listen humbly, love deeply, and shift power.” With a powerful conviction like that, Pete is a good choice to help SMART to make progress as an organization in all kinds of important ways.

Learn more about the Take 5 Spotlight series and see others who have been profiled.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline @ 988, https://988lifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

It’s true that money can’t buy love, but foundations, government and corporate funders provide monetary resources that can buy organizations a whole lot of other things. And connecting with those sources of funding is now Kenya Welch’s job at SMART.

Kenya is the new Grant Writer Consultant and she says it’s her job to connect SMART with funding. Funding that can then help SMART’s reach the most people possible with our program. Funding can help us to do anything from putting new staff resources in place, providing scholarships for training facilitators, and making sure that volunteers are supported in the best ways possible.

Kenya came to SMART believing that people in crisis are sometimes hiding in plain sight, and this reality touched her in deep way, “I like helping new people become more aware about how substance use impacts, often devastates, families and communities. I think organizations like SMART Recovery are critical to making the world a kinder place for people in recovery and their families.”

In previous positions Kenya has worked to improve underserved and overlooked community members. She discovered how much substance use disorders intersect with many other issues like poverty, employment, education, and mass incarceration.

Here are Kenya’s responses to the Take 5 Spotlight questions:

- Are there tasks you perform regularly during your workday? I do a great deal of reading, researching and writing about topics related to recovery and the many communities that it impacts.

- What are a couple of the ways you interact and coordinate your job with national office staff? I get to coordinate with team members to discuss new funding opportunities, to learn about their work, and to discover ways SMART can take advantage of funding opportunities.

- What is one of the ways that you think you personally make/want to make a difference at SMART? I want to help connect SMART to funders so that we can increase our capacity and reach more people who need help.

- What is your message to all those dedicated SMART volunteers across the country? Thank you for the important and often difficult work that you do!

- What kinds of things are you interested in outside of work? Any hobbies? I love travelling & exploring new places, spending time with family, listening to live music, and trying to keep up with my 8-year-old son. I also enjoy renovating houses- I’ve redone 3 houses in the last 5 years!

So, if Kenya is not busy packing her bags to go places, checking out live music, or making sure her power tools are charged, she can probably be found working to connect SMART with people who can write big checks! And it’s to SMART’s benefits that she is now connected to us.

Learn more about the Take 5 Spotlight series and see others who have been profiled.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline @ 988, https://988lifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

SEAN FOGLER AND WILLIAM STAUFFER – AUG 15, 2022

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Op-ed

Today drug overdose deaths will claim almost three hundred American lives — thanks to stigma. The labels and stereotypes so many of us use are stigma in action, and separate us from those we mark as inferior, people to avoid. We judge and discriminate, sometimes unknowingly, without intent to do harm, and too often by design.

But those of us who use drugs, have struggled with addiction, or are in recovery (as both of us are), are left, voiceless, rejected, and disconnected from everything that makes us human. This is often the point of stigma. Many believe if we punish and shame those who use drugs and sever their social connections, they will stop.

It’s never that simple, and this costs us valuable lives. Stigma is deadly. Stigma is a barrier to seeking help, participating in, or staying engaged with drug and alcohol treatment programs.

It impedes access to, and the delivery of, equitable high-quality life-saving care in every corner of our society, especially in our healthcare and criminal justice settings. And it prevents support for and the implementation of effective policies and programs that work.

The drug policy approach our society has embraced is an insurmountable barrier to saving lives and helping people thrive in recovery. It is the perfect fuel to amplify the health, social, economic, and legal harms associated with drugs and the policies we use to control them.

Different segments of the drug advocacy community have focused on various negative aspects of stigma. From privacy rights, disparate insurance and funding standards, access to quality and equitable care, to criminalization and the endless collateral consequences, stigma has always played the lead role in the ‘war on drugs’.

To effectively address drug use and overdose in America, we need a fundamental shift in how we see drugs, the people who use drugs, and the disease of addiction. We need to be seen and treated as complete humans, included, part of the tribe. This is the path to saving lives and healing communities.

To explore the impact of stigma on people who use drugs and those in recovery we surveyed over 30,000 people from across the United States on their perceptions of various aspects of social stigma. Our findings demonstrate stigma is high and widespread across the nation and expose the wide range of false perceptions, myths, and misinformation that underpin our policies and practices. These perceptions are the force that fuel the stigma that is more deadly than any drug and the primary driver of overdose deaths.

Over 70 percent of our survey respondents believe that society at large considers individuals who use drugs to be outcasts and views individuals who are dependent on drugs as having moderate, low, or no chance of maintaining recovery. This has far-reaching policy and practice implications. leads us to rarely provide the right dose and duration of high-quality evidence-based care which research demonstrates is at least 90 days. It is also a flawed perception since 75 percent of people who identify as having a substance use problem in their lifetime recover.

Imagine a medical professional shaming a person experiencing a cardiac arrest regarding their lifestyle choices, or worse, withholding treatment because they believe they did it to themselves. We would insist on disciplinary action and demand ethical treatment. People with substance use issues face this type of derision every day and in every system.

To address stigma, we need to examine our perceptions and approach to drugs and the people that use them. We need to design interventions that challenge our thinking and drive our systems and the people working in them to change. We need to include people with lived experience at every level, guiding policy, practice, and the systemic change we want to see.

We need to educate communities on and enforce the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. And we need to create a federal Bill of Rights that protects persons with substance use issues to ensure fair, unbiased evidence-based treatment, that honors the dignity and humanity of the individual, as we would expect with the treatment of any other disease.

The uninformed attitudes we have about drugs and the people that use them are deadly. To protect life, help people find a recovery path, and stop the painful and preventable loss of life we need to listen, at every stage of the policy-making process, to the very people so many deride.

Sean Fogler is a physician living in long-term recovery and co-founder of Elevyst, a public health consulting group. William Stauffer is the executive director of the Pennsylvania Recovery Organizations Alliance and and teaches at Misericordia University in Dallas, Pennsylvania.

First Published August 15, 2022, 12:00am

Link to Pittsburgh Post-Gazette HERE

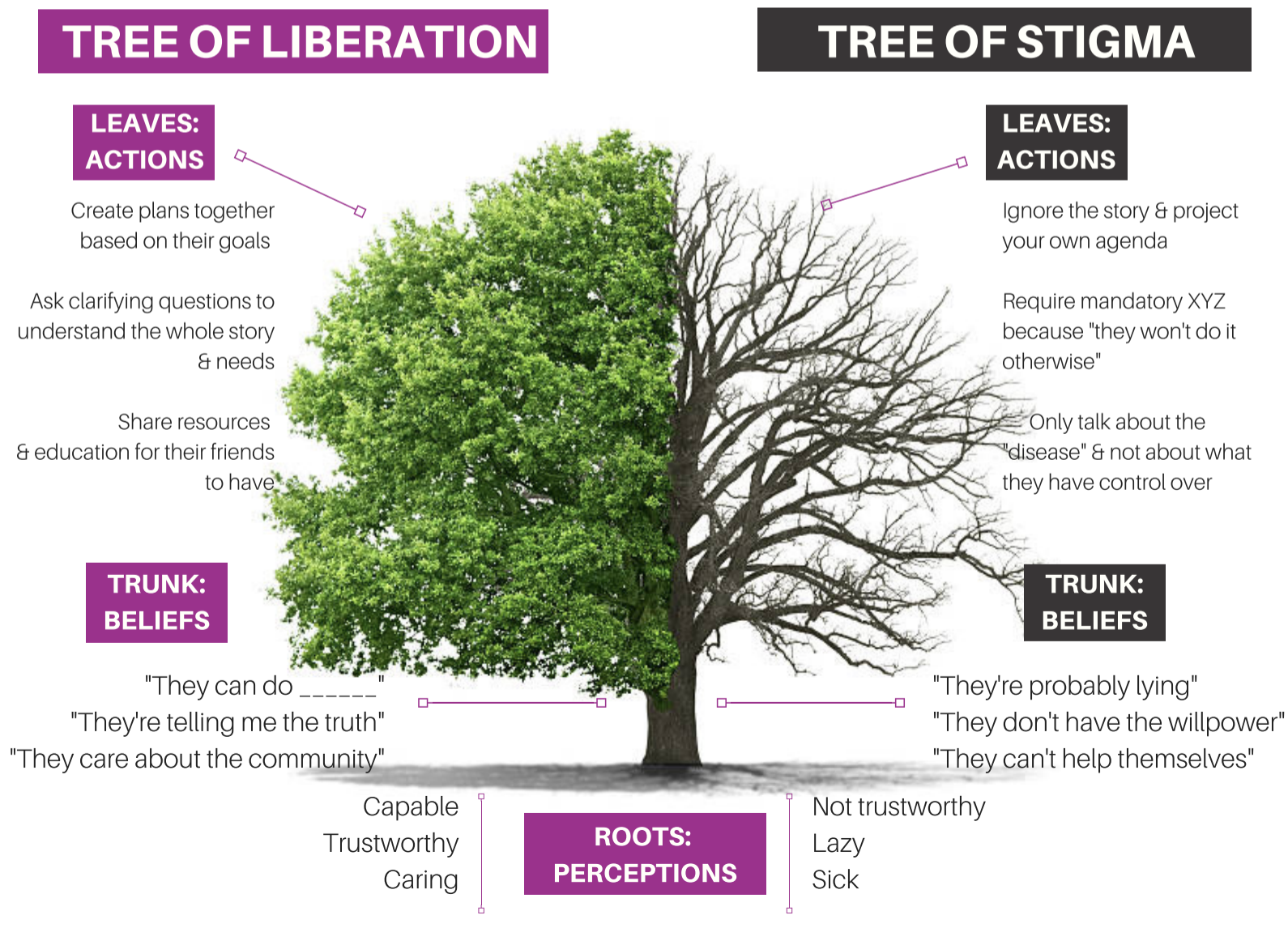

I recently stumbled on this educational page about stigma from the National Harm Reduction Coalition.

It’s well done and illuminates the assumptions and goals for their stigma reduction efforts. They frame responding to drug use as a choice between liberation and stigma, with harm reduction as the path to liberation.

While it may work for many (maybe most) people who use drugs, I’m concerned that it doesn’t work well for people with addiction and might require some modification if it’s intended to be helpful to this minority of people who use drugs.

They define stigma as follows:

Stigma is a social process linked to power and control, which leads to creating stereotypes and assigning labels to those that are considered to deviate from the norm or to behave “badly.” Stigma creates the social conditions that make people who use drugs believe they are not deserving of being treated with dignity and respect, perpetuating feelings of fear and isolation.

I’d emphasize isolation from their definition. To me, that is the essence of stigmatization. I see it as an evolutionary reaction to perceived threats, seeking to isolate the perceived threat from the rest of the community. That threat could be a disease, a behavior, or anything that might appear to be a threat to the health, function, structure, status, or social order of the community. (It’s important to recognize that something doesn’t need to be an actual threat and that evolution would favor the over-identification of threats. Further, many false positives will probably be aligned with the prevailing social structures, and ones that are not will often have post-hoc explanations that are aligned with those structures.)

In their framework, the goal for people who use drugs is liberation, which is described as such:

Liberation is the act of setting someone free from imprisonment, slavery or oppression.

In the context of drug use and sex work, liberation is about freedom from thoughts or behavior — ”the way it’s supposed to be” — and how we are conditioned to perpetuate harms to others.

The first statement emphasizes freedom — freedom from external forces infringing on liberty and dignity. The second statement adds freedom from harmful traditions and orthodoxies.

This strikes me as a place where it’s important to distinguish between people with addiction and other people who use drugs.

The elements above may provide a pathway to liberation from social responses to a freely chosen behavior. And, for most people who use drugs, it is freely chosen behavior.

The illness of addiction, however, is characterized by impaired control over use. Further, the experience of impaired control over drug use is an experience of oppression. This illness and impaired control constitutes a barrier to a life organized around the person’s goals, values, and priorities. These barriers extend into all areas of life — the relational, occupational, emotional, moral, civic, and spiritual selves.

Where the illness of addiction is present, freedom from external oppression cannot deliver liberation, though it may remove some barriers to liberation and recovery.

So, how might this change the tree of stigma?

My previous posts on recovery-oriented harm reduction shed some light on my ideas. However, reviewing the tree of stigma got me thinking that, while I differentiated drug use in addiction from other drug use, I didn’t speak explicitly enough to drug use by people without addiction.

Most drug use is not addiction. There is a broad spectrum of alcohol and other drug use. Addiction is at the extreme of the problematic end of that spectrum. We should not presume that the principles that apply to the problem of addiction are applicable to other AOD use.

ROHR is committed to improving the wellbeing of all people who use drugs. ROHR services are not contingent on current AOD use, recovery status, motivation, or goals. Further, their dignity, respect, and concern for their rights are not contingent on any of these factors.

Addiction is an illness. The defining characteristic of the disease of addiction is impaired control related to their substance use. We should not presume that the principles that apply to other people who use drugs will be applicable to people with addiction.

Drug use in addiction is not freely chosen. Because the disease of addiction affects the ability to choose, drug use by people with addiction should not be viewed as a lifestyle choice or manifestation of free will to be protected. It is not a expression of personal liberty, it is a symptom of an illness and indicates compromised personal agency.

An emphasis on client choice—no coercion. While addiction indicates an impaired ability to make choices about AOD use, service providers should not engage in coercive tactics to engage clients in services. Service engagement should be voluntary. Where other systems (legal, professional, child protection, etc.) use coercive pressure, service providers should be cautious that they do not participate in the disenfranchisement or stigmatization of people with addiction. Some might wonder whether ROHR is appropriate for people who use drugs and recovery is not an appropriate endpoint. (Because it isn’t indicated and/or wanted.) Its goal is to assure that hope and a visible pathway to full and stable recovery is available to all for whom it is indicated, but never to impose it.

For those with addiction, full recovery is the ideal outcome. People with addiction, the systems that work with them, and the people around them often begin to lower expectations for recovery. In some cases, this professional despair emerges in the context of inadequate resources. In others, it stems from working in systems that never offer an opportunity to witness recovery. Whatever the reason, maintaining a vision of full recovery (complete and enduring cessation of all AOD-related problems and the movement toward global health) as the ideal outcome is critical. Just as we would for any other treatable chronic illness.

The concept of recovery can be inclusive — it can include partial, serial, etc. While my ROHR writing has argued for a distinction between recovery and harm reduction, Bill White has described paths that can be considered precursors (precovery) to full recovery.

Recovery is possible for any person with addiction. ROHR refuses cultural, institutional, or professional pressures to treat any sub-population as incapable of recovery. ROHR recognizes the humbling experiential wisdom that many recovering people once had an abysmal clinical prognosis.

All services for people with addiction should communicate hope for recovery. ROHR recognizes that hope-based interventions are essential for enhancing motivation to recover and for developing community-based recovery capital. Practitioners can maintain a nonjudgmental and warm approach with active AOD use while also conveying hope for recovery. All ROHR services should inventory the signals they send to individuals and the community. As Scott Kellogg says, “at some point, you need to help build a life after you’ve saved one.”

Incremental and radical change should be supported and affirmed. As the concepts of gradualism and precovery indicate, recovery often begins with small incremental steps. These steps should not be dismissed or judged as inadequate. They should be supported and celebrated as personal accomplishments and they should not be treated as a clinical endpoint. Likewise, radical change should not be dismissed as unrealistic or unsustainable pathology.

ROHR looks beyond the individual and public health when attempting to reduce harm. ROHR wrestles with whether public health is being protected at the expense of people with addiction, whether harm is being sustained to families and communities, and whether an intervention has implications for recovery landscapes. It recognizes that the interests of people with addiction and other people who use drugs will diverge in many cases. ROHR maintains deliberate awareness of this reality and refuses to sacrifice one group for the other.

ROHR should aggressively address counter-transference. ROHR recognizes a history of providers imposing their own recovery path on clients while others enjoy vicarious nonconformity or transgression through clients. Substance use workers of all orientations are vulnerable to savior and martyr complexes. These tendencies should be openly discussed and addressed during training and ongoing supervision.

ROHR refuses to allow recovery and HR to be framed as counterforces to each other. While recognizing that most people who use drugs do not need or want recovery, for those with addiction, ROHR seeks to be a bridge to recovery and lower thresholds to recovery and avoids positioning itself as a counterforce to recovery. Recognizing that addiction/recovery has become a front in culture wars, ROHR seeks to address barriers while also being sensitive to the barriers that can be created in this context. When ROHR seeks to question the status quo, it is especially wary of attempts to differentiate from recovery that deploy strawmen, recognizing that this rhetoric is harmful to recovering communities and, therefore, to their clients’ chances of achieving stable recovery.

ROHR recognizes harm reduction can be an appropriate end for many people who use drugs, but is better pursued as a means to an end for people with addiction. ROHR views harm reduction as strategies, interventions, and ideas to reduce harm. As such, it is wary of models that frame harm reduction as an end unto itself for people with addiction. Back to Scott Kellogg’s point, “at some point, you need to help build a life after you’ve saved one.” The end we seek is recovery, or restoration, or flourishing, whatever is most appropriate for the individual or group. ROHR maintains awareness of tendencies to view harm reduction as “the thing” rather than “the thing that gets us to the thing.”

None of this is intended to suggest that anything here is bad or wrong. In the absence of addiction, this model makes a lot of sense. For most people who use drugs, it makes a lot of sense.

Historically, we failed to do a good job distinguishing between addiction and other drug use, erring on the side of categorizing far too much drug use as addictive. Appropriately, people have sought to correct this problem via professional, academic, and cultural change. (I’ve previously shared concerns about the DSM 5’s effect on the differentiation of addiction from other drug problems.) Unfortunately, this correction has resulted in the erasure of the distinction in many spaces.

This has been a good thing for people who had previously been miscategorized. They are more likely to be left alone and, where appropriate, get help that doesn’t presume addiction is the problem.

However, I’m increasingly concerned about the needs of people with addiction having their needs understood, respected, and responded to appropriately.

As the spectrum of drug use is increasingly being professionally, academically, and culturally understood as a manifestation of liberty and free choice, people with impaired control are likely to be misunderstood and stigmatized.

There’s no inherent incompatibility, but there is some tension. The needs and interests of people without addiction who use drugs, people with addiction who use drugs, people in recovery from addiction, the loved ones of those three groups, and the communities/communities of those three groups are not always aligned.

Recognizing these misaligned needs/interests is essential to developing models, systems, and policies that consider and respond to the needs of everyone. This would be important if these were stable and discrete categories, but the need seems even more important when we consider that people may move through these categories and may be in more than one category at the same time.

Change happens slowly. It is often much slower than most of us care for, particularly in recovery. Just as the disease of chemical addiction doesn’t happen overnight, neither does recovery. There are actually 6 stages in the process.

Change happens slowly. It is often much slower than most of us care for, particularly in recovery. Just as the disease of chemical addiction doesn’t happen overnight, neither does recovery. There are actually 6 stages in the process.

Stage 1: Pre-contemplation: This is the time for most alcoholics and addicts when they are beginning to experience negative consequences and unmanageability as a result of their using. They are often wanting to minimize consequences, but not yet ready to give up the alcohol or drugs. There is not a great deal of desire to change. Their defenses and rationalizations are in high gear.

Stage 2: Contemplation: In this stage the alcoholic or addict recognizes their using is a problem, but they often waiver on what to do about it. It is common at this stage to procrastinate and put off any real change. Statements such as, “I’ll go to treatment next month,” or “I’ll cut back after the holidays” are the norm. People can stay stuck at this stage for a long time as they try to cut back or attempt controlled drinking or using.

Stage 3: Preparation: This is the point in the change process when most alcoholics or addicts move away from just thinking about the problem and start seriously considering the solution. An alcoholic or addict may still be drinking or using, but now they are making more serious plans for change. They begin taking meaningful steps toward recovery.

Stage 4: Action: Many people mistakenly believe this is the first step in the change process, because this is when the alcohol or addict begins executing the first steps in their recovery process. It may begin with attending 12 step meetings, going to outpatient treatment, or even entering a residential treatment program. Recovery does not end at this stage. This is just a step in the process.

Stage 5: Maintenance: The focus in this stage of the process is sustaining the changes made in the action stage. It is about recovery behaviors becoming second nature, like going to meetings, calling a sponsor, doing service work. It is also about adopting healthy coping strategies, avoiding triggers and identifying chemical-free ways of having fun.

Stage 6: Termination: In the last stage, people can look in the mirror and confidently say that they are a different and improved person. What makes this stage so important is that recovering alcoholics and addicts are happy with where they are and don’t want to return to their old lifestyle. Even though they may have given up things to be clean, they know their current life is better. Unlike the name suggests, this is not the end of the change process.

It is very important to point out that the stages of change in recovery are fluid. How these stages play out in recovery is highly dependent on the individual. There is no set time limit on when people in recovery progress to the next stage. In reality, recovery is a lifelong process that requires continual evaluation and modification as you progress in your own recovery journey.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The tragedy of Scotland’s drug-related death figures has been in my mind this last week or so. The media may have largely moved on, but those of us who work in the field of addiction, those of us who know individuals who have died and those of us with lived experience of addiction will not be able to do the same.

Why has Scotland got the highest drug death rates in Europe? It’s not a question with a straightforward answer. Deprivation is part of the picture, but it is not the whole picture. It is true that you are much more likely to die of drug related causes in a deprived vs. a wealthy area, but when we compare mortality rates in similarly deprived areas elsewhere, Scotland’s statistics are clearly worse.

Polydrug use is now the norm and the illicit market is flooded with cheap benzodiazepines, some of which are potent. Alcohol problems are prevalent. Physical and mental health comorbidities are commonplace.. Polypharmacy is an issue, with a significant proportion of people in treatment on prescribed sedatives (e.g., gabapentinoids, antipsychotics, sedative antidepressants etc.). Access to treatment varies according to geography and, for various reasons, progress on improving this is slow.

On an individual level despair drives drug use. On the day the drug deaths were announced, I listened to a man on the radio explain how hard he had found it to grow up in a deprived area of Glasgow (Pollok) and how drugs had brought him relief from the challenges. Clearly there may have been better responses to the lack of hope he experienced, but if there were, they were elusive.

There is a culture of addiction that permeates in Scotland. William White has captured this theme.. Drug users are often embedded in social networks where the language of drug use, beliefs about drugs, attitudes values and behaviours around use are deeply ingrained and part of a daily routine. Behaviours are driven by short term rewards. There are few role models or peer leaders who are offering alternatives to the daily loop of despair, where the primary focus of that 24 hours is finding the resources to buy drugs, finding a source for supply, and using. Quality of life is deeply impaired. Desperation becomes a unwelcome but understandable bedfellow. Changing unhelpful social networks has been a bit of a policy priority blind spot.

Medication assisted treatment (MAT) is an evidenced-based way to reduce harms. Setting standards for access to treatment, quality of treatment and effective therapeutic and social interventions is a no-brainer. The MAT standards aim to improve outcomes. There is a highly professional MAT Standards website just launched with nicely produced information leaflets for frontline staff and for the commissioning bodies (ADPs). But I see a problem – a kind of mammoth in the morning room. What is it? Well, nothing other than MAT is mentioned.

There is no mention, for instance, of another central plank of the Scottish Government’s National Mission – the work to improve access to and capacity in our residential rehabilitation system. This lack of joined up thinking (how would one get from MAT to rehab?) is a blind spot, not only on the website, but indeed in the official Scottish Government paper on the standards.

Impressed by the emphasis on choice embedded in the standards, I asked a question at a MAT event about leaving MAT treatment. I wanted to know what channels and options the architects had in mind. I was told that when people want to leave specialist prescribing services, they can choose to go to primary care prescribing services instead. Kafka came to mind.

To the casual eye, it would appear that MAT is like the Hotel California: you can check in to MAT, but don’t expect to ever leave. Perhaps there is an unspoken doctrine behind this – the public health risks of facilitating meaningful choice for individuals and their families beyond MAT are felt to be too high for the MAT Standards architects to support.

This absurdity – both the thwarting of the abstinence goals of some individuals who will want to choose MAT initially and the perplexing neglect of other treatment options – also part of the Scottish Government’s National Mission – suggests a fundamental disconnect.

While I absolutely agree that MAT should be offered to everyone who might benefit, our policy makers and commissioners need to be aware of the tension between pursuing logical public health approaches to the exclusion of individual health choices. I have lost count of the number of people I’ve treated over the years who have told me they’ve been on MAT for years and no professional ever discussed rehab with them. It’s a depressing fact that some people get to rehab because of treatment professionals and some people get to rehab despite treatment professionals. Rehab is not a silver bullet, but it is a viable option. Too often, there’s a brick wall where a door should be.

And I’m not letting residential treatment services and intensive community programmes off the hook. Rehab also needs to find ways to bridge this abyss. All rehabs need to have a fundamental harm reduction strategy in place, give robust overdose prevention training and dispense naloxone kits to their at-risk residents. They absolutely must be able to connect those who do not complete treatment or who relapse in aftercare back into community treatment quickly and not stigmatise MAT. Those bridges are not always in place. Silo mindsets serve service users poorly.

Although it’s been called for over many years – in papers, policies and by lobby/advocacy groups – we are nowhere near reaching a recovery-oriented system of care. Having robust interfaces between all parts of the treatment system is essential if we are to reduce harm. People fall out of treatment and return to use in both MAT and rehab services. To keep them safe, outreach, harm reduction approaches and early re-entry to treatment are key. As I say, those connections often don’t exist. We need to plug them.

“Recovery-oriented systems of care (ROSC) are networks of formal and informal services developed and mobilised to sustain long-term recovery for individuals and families impacted by severe substance use disorders. The “system” in ROSC is not a local, state, or federal treatment agency but a macro-level organisation of a community, a state, or a nation. ROSC initiatives provide the physical, psychological, cultural, and social space within local communities in which personal and family recovery can flourish.”

William White

I don’t believe it is in the interests of those individuals (and their families) who struggle with dependence on substances for us to maintain treatment turf wars. We can have harm reduction and recovery. We can have MAT and abstinence. We can have outpatient treatment and residential rehab. A joined-up, comprehensive treatment system with strong links between its component parts will serve individuals best.

I have worked in community clinics where I prescribed opiate substitution treatment which reduced harms and improved lives. I would gladly do the same if I went back into that setting. The MAT Standards raise the bar – it’s clear that treatment should be about much more than a prescription. If MAT helps people and their families reach their goals, then there is much to celebrate. But not everyone wants MAT, not everyone reaches their goals in MAT services and not everyone wants to stay in MAT forever.

When we silo issues, we end up with solutions that are in conflict with each other

Cameron Sinclair

Individuals deserve meaningful choices, but those choices are elusive if we operate our treatment system in silos and are not using shared decision making with our clients and patients – offering the range of options available and seeking to mitigate risks.

The problem of developing policy strands and treatment services in hermetically sealed silos is that we end up with this disconnect (and, if we are honest, conflict of solutions). If we have no exit route and no bridge to other evidence-based treatments we are seriously letting people down. If we want to give those we are trying to help the best chance, we need to bulldoze brick walls and get better at building bridges.

Continue the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

Photo credit: Kirkikis

Mercy Bell’s relationship with alcohol started in college as a way to thwart the uneasiness she felt inside. It led her to a “recovery or else” situation. She used multiple paths and experiences along her journey to recovery. Today, Mercy is the co-owner of Sober Voices and Sourcing Voices, with Alyssa Hart. Their mission is “to amplify and celebrate all voices and all experiences on the journey of recovery and mental health”, especially college students, LGBTQ+, and BIPOC.

In this podcast, Mercy talks about:

- Having a “high bottom” that most people couldn’t see and using many paths to recovery

- Serendipitously meeting Alyssa Hart who was creating an online sober event, FLOW

- Being a “buffet grazer” of recovery

- Being impressed with the technology and ecosystem Alyssa was using for a grassroots style recovery movement during the pandemic

- The inspiration to start Sober Voices for online recovery events and Sourcing Voices, the technology platform where recovery content lives

- Why having a diversity of voices and stories is key to having people relate and connect

- The mission of Sober Voices and why they chose to use the words Amplify and Celebrate

- Finding SMART while planning for FLOW 2021

- The future goals for Sober Voices and Sourcing Voices

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline @ 988, https://988lifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Three years ago Bernie Quartaroli found SMART Recovery among the multiple pathways presented to him in detox, and he was hooked. Today, he facilitates two online meetings and one in-person meeting. The gratitude and fulfillment he experiences as a facilitator keeps him motivated and passionate about helping others on their journey.

Find Bernie’s online SMART meeting #5109

Find Bernie’s online SMART meeting #5113

Find Bernie’s in-person SMART meeting #6505

Learn more about becoming a SMART volunteer

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline @ 988, https://988lifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Steve Kind’s alcohol use started in high school and progressed to a real problem over the years. After several attempts at treatment programs, he met a counselor who knew about SMART and suggested he look into the program. It was like a lightning bolt that propelled him to success over his addiction. He now facilitates meetings and is helping others live their Life Beyond Addiction.

Listen to Steve’s podcast: Waiting for Someone to Show Up

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline @ 988, https://988lifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Earlier this month, Dr. Thomas McLellan, Dr George Koob, and Dr Nora Volkow published a viewpoint article at JAMA titled Preaddiction—A Missing Concept for Treating Substance Use Disorders. It is an important piece. The concept of preaddiction could dramatically expand our intervention strategies and better help us address the horrific consequences of harmful substance use across our society. As substance misuse and addiction are a leading if not the leading public health challenge we face, this is a welcomed articulation of these complex conditions. Preaddiction and its relationship to addiction as a parallel of prediabetes to diabetes could change what we do to help people heal from SUDs and save lives. This is a timely statement of a vital conceptual model we need to consider widely adopting.

The piece calls to reconceptualize substance use on a spectrum from harmful misuse to addiction and to focus our attention on preaddiction as it presents in early-stage misuse. As a decades long clinician, this fits with how I would work with people who were grappling with substance misuse in my work over the years. For persons experiencing problematic use, we need to consider if such persons are experiencing either an early-stage severe SUD or their substance use issues are a less severe from that can be addressed by lifestyle modifications that does not necessarily include cessation of substance use. Impaired control over use is central to how we explore this with those we serve. As noted in their article:

“Scientific findings now suggest impaired control as the core defining diagnostic construct, hypothesized to be the result of gradual use-related damage to brain circuits controlling reward sensitivity, motivation, self-regulation, negative emotional states, and stress tolerance”

As with diabetes, people with substance use disorders are experiencing a complex condition that includes a myriad of genetic and environmental factors. Impaired control is the core defining issue I would sit and discuss with persons I was working with in respect to exploring harmful substance use. Not everyone I worked with was addicted. As an aside, we do not see people in our care in these earlier stages as often as we should. We must expand and fund services for persons examining their risk factors. Persons in a preaddiction phase could address trauma, develop better coping mechanisms and reduce reliance on substance use as a coping strategy. Others will likely continue to experience impaired control as their use would progress into our classic understanding of addiction in which cessation of the use of substances became a more central facet in our treatment focus. Some people (like me) with early onset severe forms of the condition end up moving very swiftly from misuse, through preaddiction into addiction. This model could also help identify persons like me who are at the highest risk for a severe SUD earlier in life because of the genetic and environmental influences that make addiction a likely outcome.

Three areas were adopting a model that includes preaddiction could help us improve care for persons experiencing harmful substance use:

- Normalizing Substance Use Monitoring in Routine Medical Care – Articulating preaddiction can move these types of discussions more centrally into general medical practice settings. Getting people assistance to identify ways to understand their risks and change their lifestyles in routine medical care is paramount. It would support wellness strategies that can help people avoid addiction before they cross this threshold into loss of control. These discussions should be routine and occur when you have an annual medical checkup, just as it would if your blood sugars indicate you are moving into prediabetes. Every American should know their risk factors in relation to harmful substance use and understand what resources are available to help them maintain wellness.

This would also serve to help us expand how the public understands early-stage substance misuse and its progression. Like diabetes, there are complex genetic and environmental factors that influence its development. Medical communities and the public understand this paradigm in respect to diabetes. Moving conversations about substance use into general medical care using preaddiction as part of our model to explore and monitor risk factors and potential interventions would help normalize this highly stigmatized condition. This would save lives and normalize these types of medical conversations in ways we have failed to achieve to date.

- Early Interventions – As the authors note, we have focused nearly all of our interventions on later stage addiction. Addiction often, but not always is a condition that presents in early life, yet we tend to ignore it until it reaches high severity in later years. We ignore it and let it run its course until it gets harder to address! Here in my home state of Pennsylvania, I worked a few years back to hold a hearing in our General Assembly on the loss of our care structure for young people. We have actually lost ground on our young person’s SUD care infrastructure, and not just here in PA, but nationally. If this was any other public health crisis, we would focus on early intervention! Let’s do that.

Substance misuse can be conceptualized as a communicable condition, it spreads primarily among young people. Wellness works the same way when we normalize and support healing strategies to help people who are experiencing substance use issues heal. We ignore the signs until they reach elephant on coffee table dimensions. In contrast, we stop talking with people about prevention when they turn 18 years old, which makes no sense in a public health model. As the saying goes, we need to stop pulling people out of the water and go upstream to stop them from falling in. Preaddiction as part of our model in understanding and articulating to continuum of harmful substance use can help us focus on earlier interventions, which may well reduce the number of people who become addicted. More resources to help people heal earlier in the continuum means fewer people falling into the river. Deploying a preaddiction model could reduce the time that people are progressing through a substance use condition. We can save lives and help more people flourish in this way.

- Developing a more nuanced understanding of wellness and recovery. There have been a myriad of attempts to develop all-encompassing definitions for recovery over the years. As the article notes, most people who initiate substance use do not progress to full addiction. Healing and wellness from a substance use condition is also not a one size fits all process. The common understanding of recovery centers on the cessation of substance use and changed lifestyle as central pillars of recovery. Loss of control through damaged brain circuits defines addiction. Healing from a process of harmful substance misuse for those in a preaddiction phase is different in both degree and type than recovery for a person with a severe substance use disorder who experience the impaired control over use as highlighted by the authors. Articulating healing in a preaddiction model can help develop more nuanced definitions of recovery across the substance use healing and recovery spectrum that include persons who do not experience the severe form of the condition.

It is readily apparent to anyone who is even casually observing that harmful substance use is dramatically increasing across our society. Increased access to mood altering substances, increased social stress and greater social isolation are significant environmental factors that lead to people using substances to cope with challenges they face. We also know that addiction is influenced by a myriad of factors. Researchers are examining the complex genetic and epigenetic influences of how people use substances. Like diabetes, some are protective, and others increase risk for substance related conditions. The preaddiction model fits with what is occurring in respect to the continuum of harmful substance use to addiction and provides us additional off ramps to help save lives and heal communities.

There has never been a time in which we need to develop unifying concepts and systematize earlier stage interventions for harmful substance use issues in ways that can be readily understood in front line medical practice and by the public.

I hope we can embrace it as an important way to improve our care system.