I received some interesting questions regarding my post on critique, so I figure it is time, as Paul Harvey says, to tell the rest of the story (while I have the time). Anyone who has studied politics and philosophy knows that for every argument there are counterarguments and alternative theories that come from perceived weaknesses in specific theories. There are such arguments in relation to critique as well. I will generally structure this essay to answer some of the questions I have received, but I won’t be taking them one by one because each question ties into another so composition is more fitting.

Liberation for whom

In the last piece, I noted that critique is a liberatory idea. It rests on what philosopher’s call an a priori. A priori means that certain beliefs are baked into something before it is even experienced or tested. Liberation implies the opposite condition exists automatically – ie domination and oppression are a priori. But who are we talking about when we assume some people are oppressed and some are not?

Well, it actually means a lot of people are dominated by the conceptions of substance use that our society holds. From the individual who has lost control of their substance use and feels ashamed, to the politician who feels they have no other choice but to build another prison. It implies families who suffer the daily torment stuck in the orbit of their destructive loved ones. It means scientists who are bound by specific terms and methods of measurement thought to be the most valid way to define and observe substance use disorders. Clinicians experience this as “best practices” bolstered by ethical standards and ideas of “efficacy.” Doctors are bound to their own tools, largely medicine, and clinics are bound by laws and funding that determine what a clinic can and cannot do. All of this is informed by what we believe to be true about addiction and substance use. We are all dominated by specific ideas related to substance use. These ideas limit us to fields of action, and fields of thought, and these concepts bound our ideas of what is and is not possible when we speak about addiction.

One weakness in liberatory ideas is that they can be non-specific and involve an idea of utopia or a perfect world. There are various ways to respond to this but in essence, it is a specific question – how do we define freedom, and who gets to have it?

In the case of substance use disorders, however, we have to take a step back. We have to recognize that how a politician or a doctor views substance use disorders also limits how others see it, this is related to the way power is entrusted to specific social roles, giving weight and validity to those opinions. Or consider how science has the authority to designate it as a disease or quantify how much is bad or indicative of illness. These are not unrelated to how the individual using substances sees themselves, nor is it unrelated to how their family views them. In fact, all of these are tied to specific socially constructed matrices of assumptions we make about substance use as a whole. They inform one another and are in constant dialogue. And wires get crossed all the time.

For example, a parent may plead with a family physician to put their child on medication (having read about how medication reduces death) because they do not want to lose their child to overdose. However, the child themselves may not want it, and may not even see their substance use as a problem. Or consider the spouse who wants their partner to quit drinking. They don’t want their partner to moderate, or try to control it, they want them to stop. While their partner might be willing to try medication, therapy, and moderation. Or consider the old timer in N.A. approached by a young person who says they think medication might be a better option for them. Or consider the methadone client sitting in the parking lot after driving an hour to the clinic before work, thinking to themselves that there has a better way to get free of their addiction.

Next, we have to consider the system in which we treat substance use. A gentrified, class-based system, that is more reliant on whether one can pay for services than whether one needs those services or not. The poor get one type of care, and the more fortunate get access to another type of care. Those who are already facing oppression outside of their substance use face imprisonment, not treatment. The only truly accessible and ubiquitous institutions that will serve everyone are aimed at specific outcomes (abstinence), which may or may not be what individuals need or want. We cannot pretend that any area of the field is absolutely just, equitable, or fair. Nor can we pretend that things like insurance, profit, wages, housing, employment, and health systems don’t play a serious role in whether one recovers or not. Who gets care, and who gets to go to jail is a political, not a clinical reality. Who gets one type of treatment over another, is a matter of status, not a matter of necessity. When we consider how we frame substance use disorders in society, is it any wonder that we allow such obvious systemic savagery to literally kill and deny some while elevating and compassionately treating the privileged? In this way, we accept something so gravely unjust and we become bound and held captive by its cruel mechanisms and unjust outcomes.

And yet, simultaneously we also understand that there is no perfect system that can respond to all of this. This is where the main weakness of critical lenses becomes apparent. And most of us walk away at this point and say, “Well it is a cool idea but it isn’t pragmatic. No system or set of ideas can be free from all of these delimiting and unfair facts.” We believe that perfection of concepts and ensuing systems must be achieved for it to be pragmatic.

The critical mistake

In many ways at this juncture, we do the work of oppression. That’s right, we become operative agents who promote injustice and oppression precisely because we write off the Utopia that we feel is unrealistic. The absent but implicit overture is that in doing so we further entrench the way things are by assuming they can never change. Or by believing that the end goal is an unreachable utopia, we then have no choice but to accept the status quo and at best, incremental change. This essentially throws out the entire critical project, at the expense of those who are most negatively affected because we “just don’t see how alternatives would be realistic.” This is a trap.

Circumventions

We can start from a different place altogether. Already in my last post, I offered a rubric for evaluating what we do and how we think about substance use disorders in society. This rubric has us rely on critical values, rather than systemically offered cues, to make judgments about how we are responding to substance use in society.

Let me offer an example we are probably all familiar with. An insurance company agrees to pay for four days of care in an inpatient facility for your client. Clinically, you surmise they will need a minimum of 90 days, given their severity, and the outcome goal you and the client agreed upon, which you will periodically reevaluate and adjust according to progress made by the client. It is clear you have to fight to justify every day that this client requires care. You are prepared for this because this is how the system works. So you produce the necessary clinical documentation and rationalizations that meet or exceed what the system requires in order to continue care. Most of us go exactly this far. And while we have gripes about this system, it has never stopped us from participating in it, nor has it ever stopped us from producing what the system requires of us in order to function.

Let’s evaluate this in terms of critical values. Is it fair? No, in fact, it seems really unfair. Is it just? Fighting for my client is just, having to fight profit motive so I can care for people to the best of my clinical capacity is not. Does this promote equality in society? No, it feeds a machine that thrives on inequality. My client deserves care, they will get it because they can participate in an unfair system, others will not, however, even though they deserve it.

Now comes the hard part

If we take seriously and believe in critical values (not everyone does), what should our practices be in light of the above example? Having used a critical rubric we see there are a lot of shortcomings that violate the values we say that we hold. We are faced with a moral and political dilemma. If we believe in these values we will act in ways that promote them. If we do not believe in them, we should be honest with ourselves. How do we know which one is us? Well….(drumroll)…

You know whether or not you value fairness, justice, and equality by what you do and what actions you take.

Do you organize resistance? Form a union among treatment providers with enough power to say, “No.” Do you develop underground networks of care for people who can’t pay? Do you push the system you work in to expand options, infrastructures like job placement, and housing? Do you work “off the books”? Do you testify before your state legislature, write your congressperson, rally, protest, or get arrested in front of Blu Cross Blu Shield HQ? Do you keep secret files and information about this industry, about the people left out, and about the practices that are used to exploit families and clients? Do you expose bad actors? Faulty practices? Inhumane forms of care? Do you insist your employers take a stand, and clearly state their goals? Do you bring down false advertising, and contact better business bureaus? Do you collect accounts from people who access the system? Do you talk to prisoners? Do you get fired, do people threaten to file complaints, have your license revoked, or do you insist at every turn that complete and full care of the individual is the only ethical practice there is, and you won’t participate in anything less, do you get thousands of other clinicians to agree with you? Do you walk away entirely unable to work within a system of injustice?

It is okay if you do not. But, then you need to re-evaluate what you believe about the values you do hold. Part of the problem in this field (and our nation as a whole), is that we believe that wanting to hold values is the same as holding those values. It is not. Critical values are not performative. They are not spoken, they are enacted. They are not signaled, they are put into motion. Critical values are not Tweets or complaints. They are direct confrontations with things in the world that go against critical values. Critical values mean that one actively and constantly acts in resistance to injustice and inequity.

Hopefully, this illustrates the scope of what critique actually means.

Most of us will read this and say that we work really hard. That we have no time for this, or that we do what we can when we can. Don’t beat yourself up if you are not leading a revolution. We are all taxed by the system. And the system stays in place because of the way it wears down resistance. The way we construct addiction in our society positions the clinician and the sufferer, the doctor, and the scientist- all in ways that avoid confrontation with the ruling order. That is what power does – it ensures its own continuation. Often we want to help, we want change, and we want to help people live life to the fullest, with adequate care and support. Recognizing your own fatigue when confronted by what critical practice might look like is a great place to begin to understand how critique broadens our consciousness in our everyday lives in the field. We know the problems that face the field. We’ve always known them. But we have spent far more energy adapting to injustice than we have spent fighting it. And, if nothing else, maybe that is a good place to start if a critical project is what we want.

With that said, we can see that critique is not for everyone. After all, people have lives, families to support, mortgages to pay, and interests that have nothing to do with the field. Do we not also deserve to live our own lives?

That brings us to the final problem. There is a direct correlation between our engagement in change and the deprivation of life, health, and liberty we allow to continue and be inflicted on others. Now, no one can tell you what that may mean to you, whether it drives a sense of urgency or obligation. Whether one is willing to take up risks for themselves in the fight for others is not, and cannot be generalized in America. But it is a question. A private question that I at least feel we should each attempt to ask ourselves. Rather than writing all of this off as Utopia, are we at least willing to privately confront ourselves? The shortcoming of critique is not necessarily with the theory itself, I find. In many ways, the fault exists within the self. Utopian or not, we cannot make such judgments until we are willing to act.

I saw an exchange on Twitter the other day that on first reading raised my eyebrows and created empathetic frustration. An individual was apparently being refused rehab because “he continued to use drugs”. Surely that’s the best reason for going to rehab. We don’t refuse treatment to diabetics because their diets are problematic, or because their symptoms are out of control. Indeed, we prioritise treatment in such cases.

Opening up access to rehab is a key strand in the Scottish Government’s National Mission to tackle Scotland’s drugs problem. The work the Residential Rehabilitation Development Working Group has done to support the government with this has identified problems people face when they try to access rehab and made recommendations aimed at removing barriers. There has been progress, though much work remains to be done. This week’s final DDTF report (Drug Deaths Task Force) highlights the importance of having rehab as an option in an integrated treatment system. People who may well benefit from rehab are unfortunately still finding roadblocks which are difficult to dismantle.

I spend a fair bit of time supporting efforts improve access to rehab, but while I want to see people matched to the treatments that are most closely associated with their goals, there are still legitimate reasons why rehab might not be the right choice at any given moment in time. Addiction and recovery are dynamic processes throwing up both challenges and opportunities. Circumstances change over time and presenting symptoms are often better managed more effectively and more safely in other ways.

Illicit drug use

I began to wonder about possible legitimate access problems for people who ‘continue to use’. What if someone was injecting a gramme of heroin daily? What if he/she/they was mixing this with crack, benzodiazepines and alcohol? There are few, if any, rehabs that can manage this kind of presentation safely. Many rehabs do not have doctors and nurses to assess and treat individuals. The majority do not offer detox. Some of those that do, are not using validated tools to measure withdrawal symptoms and calibrate medication in real time against the symptoms. Withdrawal complications from some drugs (alcohol and benzodiazepines for instance) can be fatal if not managed carefully.

So, the risks can be high. To support such a complex case, you would likely need medical and nursing input – probably on a 24-hour basis. Even detox units with round-the-clock nursing and medical cover could struggle to support this kind of presentation. The initial goal is likely not to be abstinence, but safety and stabilisation. Harm reduction and safety really need to be the first considerations every time. There are undoubtedly still gaps in our menu of treatment options. One of those gaps is the stabilisation unit – as identified in the DDTF report.

Prescribed medication

Another potential barrier to access is when people are not using illicit drugs but are on high doses of opioid replacement treatment. Methadone is not an easy drug to detox from and the risks are significant. There may also be a benzodiazepine prescription to consider.

Treatment needs to be humane and compassionate. The suffering that people go through as they withdraw is real. It can be mitigated against by being in a supportive environment and with the prescription of other medication to help withdrawal symptoms. That said, detoxing people from 80mls (or even 70mls of methadone) over a few weeks involves suffering at a level that I struggle with. I’m speaking from experience; I’ve prescribed for hundreds of patients undergoing opioid detoxes over the years in a setting where there is a high level of medical and nursing supervision. We don’t do high level detoxes for good reasons.

Nationally, we have no idea of outcomes when such heroic detoxes are undertaken. My fear is that completion rates will be low and relapse rates high. Relapsing to heroin after opioid detox is a risk factor for serious harm. The process of detox can trigger mental health issues including PTSD. Consent needs to be informed and the risks clarified.

Therefore, there are good reasons for setting medication thresholds for entering rehab and taking time with detox. Some of this can be done slowly with support in the community prior to rehab admission, but the idea that a high dose of opioid substitution treatment is not a legitimate concern which may prevent an early rehab admission needs to be robustly challenged.

Wrong fit, wrong time or needs more than one episode

Sometimes though, rehab is not the right fit. I have lost count of the number of people feeding back that it is ‘the hardest thing I’ve ever done’. You need to be at the right place and time in your life and the rehab itself needs to be the right fit for an individual or it needs to be able to flex to meet their needs. Sometimes the individual rehab falls short in what’s on offer. Many people will need more than one episode over several years (and other forms of community treatment and support) before they reach their goals.

The concept of readiness for rehab is a difficult one. ‘Readiness’ is not a stable thing – it shifts. It’s also susceptible to influence – we can help people get ready. In some places there is an active programme leading up to rehab that is designed to do this. Assessment is a process intended to assess readiness but can also influence it. We need to be careful and clear when we determine that somebody is ‘not ready’. Admittedly though, I’ve heard plenty of people successfully completing rehab for a second time who self-reported that they “were not ready” the first time.

Perhaps such people were there mainly to appease their family, or were avoiding a consequence, but with the passage of time, they got to a place where it was their time. It’s okay to acknowledge that the time is not right. Plainly, this should not mean that treatment and support are withdrawn – it’s just that this will be different for the moment.

Having not reached your goals through a previous episode of rehab is not a reason to prevent a future episode. “One go and you are out” is not okay. There is an often an anomaly in attitudes to MAT and to rehab when relapse occurs in (or shortly after) treatment. Darren McGarvey has aptly captured this: “Relapse on methadone – increase the dose. Relapse after rehab – rehab doesn’t work.” The evidence shows that no treatment is perfect, but persistence is likely to reap benefits.

Rehab as the saviour

When expectation of what rehab can deliver is too high, problems arise. Seeing rehab as ‘the answer’ is unhelpful. There is no one ‘answer’ to addiction. Dependent drug and alcohol use needs a multifaceted approach, best managed through a joined-up support and treatment system and assertive connections to those who know how to manage the journey best – recovery communities and individuals with lived experience.

The weight of expectation that is placed on rehab can greatly exceed the utility of rehab to deliver. Rehab is not something that is done to individuals who are passive recipients. It’s not like a course of radiotherapy or a surgical procedure. It requires active engagement and hard work.

There are practices that rehabs can employ to foster engagement. A peer worker can facilitate attendance at appointments, outreach can reconnect with those who start assessment and fall away. Information and experience sessions prior to assessment can foster hope and commitment. Once in treatment, ambivalence can give way to conviction as a person is cared for by their peers and staff and their mood, self-esteem and participation improve.

Mental Health

Mental health concerns come up not infrequently as potential obstacles to rehab. There are some specific legitimate concerns. Rehab is not usually the appropriate environment for someone who is actively contemplating or planning suicide or for someone who has an active psychosis or who is in a manic phase of bipolar disorder. Such vulnerable individuals need appropriate focussed mental health support and treatment, though I acknowledge that when they are drinking and using drugs they often fall between mental health and addiction services.

Many rehabs do not have access to in-house addiction psychiatrists and CPNs, so there may well be a limit to what can safely and appropriately be managed. It is also true though that people with addictions often pick up mental health diagnoses over time. It’s hard to be sure of a mental health diagnosis when people are using and drinking dependently and it’s important not to discriminate against those with mental health diagnoses.

We also need to remember that there are many vulnerable people in our treatment and support systems, and it is vital that we do not expose them to stress that might harm them. Assessment needs to consider this risk balance carefully. The rehab environment can be amazingly supportive and safe, but it can also be stressful. Living with a group of traumatised individuals in early recovery is not easy.

Where there are complex mental health needs, those individuals could be matched to specific rehab services which offer a higher level of support through their multidisciplinary teams, though such treatment is likely to be more expensive. It is my experience that patients with major mental health diagnoses and those labelled with most personality disorders can often be managed in a supportive way in rehab settings.

Risk to others

One striking thing about meeting needs in the rehab setting is that staff have to consider not only the needs of the individual, but the needs of the group and of other individuals in that group. There can be patterns of behaviour that make it difficult to justify an admission: e.g., recurrent impulse control issues leading to violence against others, a history of repeated arson, certain sex offences etc. Sometimes an individual may have smuggled drugs into the rehab and encouraged others to use on a previous admission, putting several people at risk. None of these things are absolute contraindications, but the needs of others have to be carefully considered.

Even where physical violence is less likely, aggressive behaviour can trigger PTSD symptoms in other residents or cause others to leave through fear. Sometimes the history suggests that problem substance use is the catalyst to such behaviour and the difficulties are less likely when use stops. Staff working in rehabs are often skilled at supporting people with impulse control issues, but there are limits. Assessments need to identify potential risks and work out if they can be mitigated, but sometimes the conclusion reached means an admission cannot not take place.

Conclusion

While the barriers to rehab which individuals and their families encounter are often non-legitimate – things that most certainly need to be challenged – there can be warranted reasons why rehab is not the right path. Sometimes work needs to be done and sometimes rehab will not be the right fit for a variety of reasons which can relate to illicit drug use and levels of prescribed drug use. Gaps in treatment provision, such as stabilisation units, need to be plugged.

Judgements about such matters are complex and we must do our utmost to ensure that shared decision-making is at the heart of our process. Decisions need to be scrutinised and appealed where necessary, to make sure that there is no discrimination, but ultimately while everyone ought to be informed about the possibility of rehab, it’s also okay to accept that there might be good reasons why rehab is not the right option right now. That doesn’t mean care is withdrawn, just that it is of a different sort – for the moment.

Continue the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

So far in this series I’ve…

In the previous post I mentioned that Tom, given his tendency toward a macro and outward-facing mindset, turned his thinking in the direction of system change.

In this post, my final one in the series, I will give an overview of how we incorporated system change and some related methods in our Recovery Alliance Initiative. And then I’ll share some concluding comments.

At this later stage in our collaboration, Tom turned our attention toward system change methodology and adding that to our work in the Alliance. So for this post, I’d like to introduce some potentially powerful ideas and practices that come from certain system change methods. These are-big picture ideas, but they also become quite specific – so the reader might find this information to be practical.

To start to consider system change more fully and specifically, the reader should consider exploring the resource Tom found. The “Collective Impact” model from Stanford University provides an insightful and practical framework. It guides us in how to go about a large change effort even at the level of a whole community (making sure you’re hitting all levels of possible change, and identifying specific elements to drive change, etc.). When Tom shared it with me, I was a bit astounded by it in a good way.

The Collective Impact model is far too large a topic to cover here but I encourage those that are interested or curious to check it out.

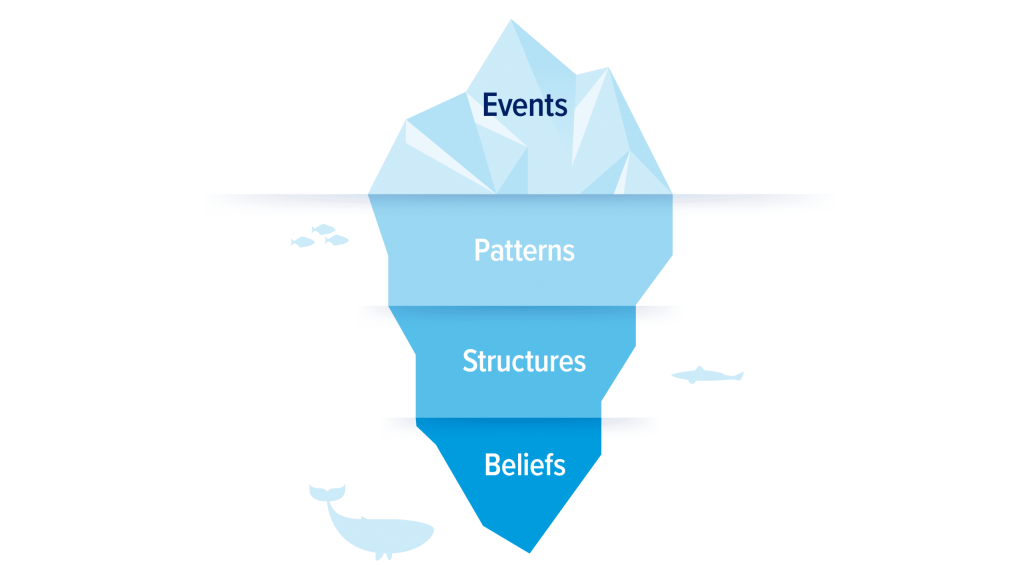

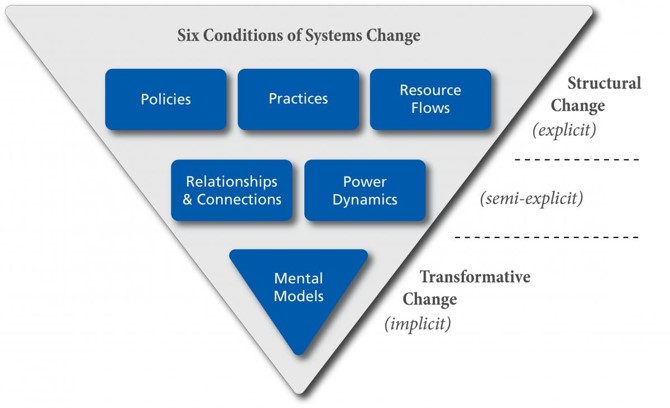

My response to Tom introducing me to the Collective Impact model was to begin to investigate system change on my own. I found a resource called “FSG: Reimagining Social Change”. Those materials include the question, “What is system change?” And their answer is that system change is about “shifting the conditions that hold a problem in place.”

Having no background in social work, public health, or policy, I was amazed by this visual that they use.

They note that it is important to consider every one of those levels in a system change effort. For example,

- you might have all the resources lined up, and be ready in terms of policy and practices;

- and you might also have the relationships and hierarchical support that you need.

But if you haven’t addressed the ideas relevant to the change you are trying to lead, and haven’t addressed people’s basic assumptions about what is in place and what you are proposing, you might be up against a whole type of stuckness that you can’t quite figure out.

In addition to the routine considerations of various resources and top-down authority, has your plan also specifically addressed the way people think about both the problem and your proposed solutions?

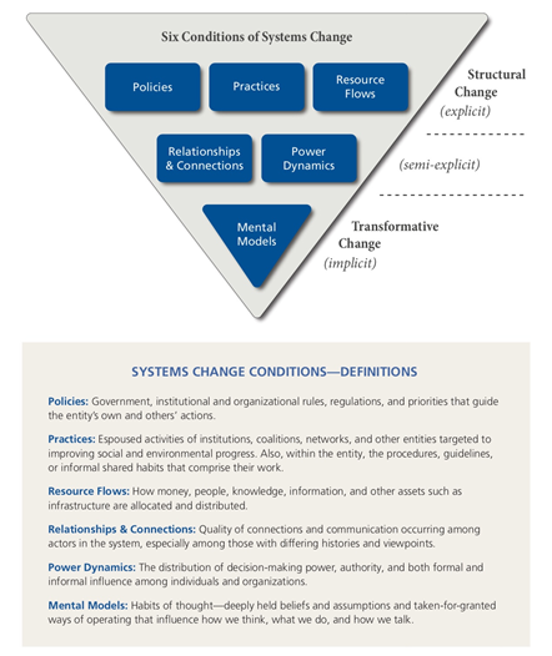

For those that might want a little more, here’s a bit of detailed language about each of these levels.

Over the years that Tom and I have conducted summit meetings, we have empowered and coached table leaders, as well as built project planning guides to help project leaders promote completion of change projects. But beyond that, we have noticed that eventually many people want to get even more practical. We have noticed that desire often arises in response to the mere process of the Summit meetings or the collaboration portion of our Alliance message – rather than to our content.

At this point you also might want to begin practical action of your own. You might be wondering what you can do right now.

In our meetings over the years, toward that end, we have suggested attendees consider a menu of possible practical actions, such as those listed below:

- Visit other sectors in your local area and get to know what each one does more specifically.

- Form a collaborative group to address a problem that coming to understand other sectors has revealed

- Become active in a collaborative work group that already exists.

- Collaborate on a project that addresses the local or county level.

- Look around your region and start to identify people, resources, and examples of collaborative work already done that would be helpful to real people in need in your local area.

- Help your own system to improve what it does or work together with other sectors in a better way, relative to Alliance concepts.

- Remember to take the long view in case coordination efforts for the person we serve, and not just the immediate or short-term view.

- Work on improving linkage with other systems by filling in the gaps of the lived experience of the people we are helping.

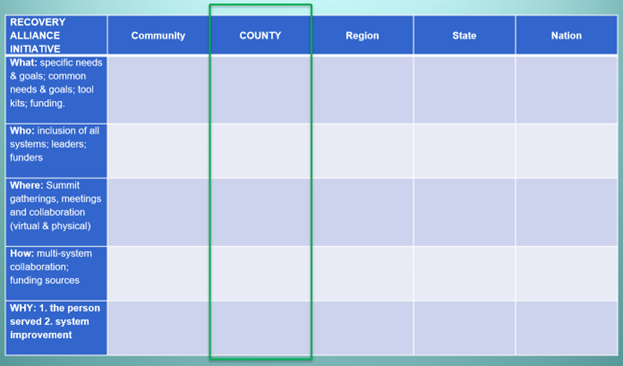

Further, I would like to provide you with one more item related to system change. Consider the grid below.

We often use this grid I made during our Summit meetings to help attendees see the big picture of Alliance potential and simultaneously narrow their focus at the level of the current meeting.

In the real example of the grid shown above, we were bringing the grid to a county-level meeting and formatted it accordingly. Within that example, consider the following that Tom or I would say to the attendees gathered from diverse sectors…

“To help you get focused today and moving toward action at the county level, consider this grid.

- At the county level, what common and specific needs and goals do you have?

- What kinds of tool kits or specific funding would be most helpful?

- What systems, leaders, and funders need to be included to move toward your county-level solutions?

- And to help get the work done, what collaborative working groups should be set up, and what meetings or gatherings are needed to support that work?

- Exactly what kind of multi-system collaboration do you think is needed to help the person we serve and to help our organizations improve what they do?”

Some Closing Comments

As I bring this series to an end, I’ll make some closing comments.

First, collaborative groups can meet in person or in videoconference. They can use the free Recovery Alliance Initiative website to message each other, upload documents, share documents and other resources with others, create a private group space for a project, and invite others into a project.

I’d also like to share what has become a favorite quote for Tom and me from one of our early and long-term Recovery Alliance Initiative supporters and Summit attendees, Terrence Walton. Terrence is the national head of all drug courts in the USA. At one of our meetings Terrence summed up the Alliance by saying that for him personally it was helpful to attend in order…

“…to know the field, to be known by the field, and to learn from the field, in order to change what needs to be changed, and improve what needs to be improved, if we are going to stay relevant, and to survive.

Lastly, I’d like to point out the latent tension found among the numerous differences between how Tom and I usually think. This tension has been a valuable source/resource.

Tom is an outward-facing macro thinker. By contrast, I’m an inward-facing thinker who is rooted in the one person we are attempting to help.

Tom often focuses on large numbers of people and teases me by saying something like, “But Brian, on the beach there are thousands of starfish. The one you throw into the water is just one.”

I’d like to say that as a clinician, I just can’t help it. To me, all our effort in the Alliance is for the sake of the one person we serve.

But in the Recovery Alliance Initiative, we focus on both.

This has proven to be fruitful. The collaboration between Tom and I (who are both quite different from each other in several important ways) has itself been a microcosm of the Alliance effort. And that difference and combination has flowed outward from the two of us. Combining our approaches has led to speaking invitations, interviews, consultations we have provided, etc., beyond what I have mentioned in this series – opportunities that his approach or my approach alone would not produce.

In closing I’ll simply say this series has been just a brief overview of a lot of effort over several years.

Below, find the references for this series as well as two suggested readings that relate to this work.

References

Boyle, M.G., White, W.L., Corrigan, P.W. & Loveland, D. L. (2001). Behavioral Health Recovery Management: A Statement of Principles.

Coon, B. (2015). Recovering Students Need Support As They Transition. Addiction Professional. 13(1): 22-26.

Crowe, K., Hennen, B. & Coon, B. March 31, 2017. A Seamless Transition: Linking College-Bound Emerging Adults with Collegiate Recovery Programs. Recovery Campus Newsletter.

DuPont, R.L., Compton, W.M., & McLellan, A.T. (2015). Five-Year Recovery: A new standard for assessing effectiveness of substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 58:1-5.

DuPont, RL & Humphreys, K (2011). A New Paradigm for Long-Term Recovery. Substance Abuse. 32:1, 1-6.

Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2011). Collective Impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9(1), 36–41.

Kloos, B., Hill, J., Thomas, E., Wandersman, A. & Elias, M. J. (2012). Community Psychology: Linking Individuals and Communities. Cengage Learning.

Osher, F.C. & Kofoe, L.L. (1989). Treatment of Patients with Psychiatric and Psychoactive Substance Abuse Disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 40(10):1025-1030.

White W, Boyle M, Loveland D. (2003). Addiction as Chronic Disease: From rhetoric to clinical application. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 3:107-30.

Recommended Reading

Goodheart, C. D. & Lansing, M. H. (1997). Treating People with Chronic Disease: A Psychological Guide. American Psychological Association: DC.

Kelly, J. F & White, W. (Eds.). (2010). Addiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research and Practice. Humana Press. (2010).

I’ve been working on a paper on recovery that is sort of a philosophical treatise on what it means to be critical regarding science, practices, and system design in relation to substance use disorders, care, and treatment. As Jason had noted in one of his earlier posts, there is plenty of criticism to go around. There are so many layers to all of this, and so much room for improvement, and growth for all of us. His post reminded me that there are several meanings tied in with the notion of critique that I feel we might benefit from a brief review of what a critical gaze of the field entails.

Sentitivity to Power

In my opinion, power is one of the most overlooked and misused aspects of critique, particularly in this field. As clinicians however we received some form of training in the idea of differential power between the client and the practitioner. This is perhaps the power differential we are all the most familiar with. It serves as a good model we can all relate to in that we are acutely aware that the relationship between ourselves and the client is not on equal terms by default. Part of our jobs in professional practice is to understand this, and mitigate the differential, while never giving up our role. We do this by active listening, involving the client in care planning, and clearly defining specific roles, goals, and outcomes we agree upon with the client. We seek to co-construct our work with the client. We tend to think of power over the client as something that should be handled with deep care, and in some ways, we tend to see power over a client as sort of an ugly way of thinking about our role. In doing so, however, in downplaying our own awareness of power, we forget that power is not personal. It is our role, not our own self through which power is expressed. Power arranges the room, therapist to client, not I to you the individual person. Outside of the therapy room, power shifts to other arrangements, for example, a business owner to a business client, as the person pays their session bill and leaves in the case of private practice. Outside of our office, the client and the therapist are merely citizens to one another. Roles and context follow the orderings of power and the design of society.

Understanding that power is not an object, nor a “thing” that one has or can grasp is important. Power is expressed through relational arrangements, often through larger systems and frameworks like professional education, credentialing, economic infrastructure, scientific discourses, and specific practices. This is as true for the person with a substance use disorder as it is for the person holding a professional license. Their identity as a sufferer, as is yours as a therapist, are both socially constructed outside of the self. This means that at some point the social articulations of the sufferer’s experience were defined as X and a person with your skills to promote healing is defined as Y. Hence, X needs Y because Y is thought to be (i.e., defined by social history) the way to ameliorate this other thing social history has constructed as X. Pathology is a discourse, as is health.

There are whole bodies of knowledge that are fashioned to define, justify, theorize, and shape pathology as a “thing” or object that exists in the world, as something that is embodied by people, and whose source, causes, origins, and manifestations are identified and itemized. These are the conditions of X. X is a product of a vast system of historical forms of knowledge and statements made about some part of X, and taken together, all of the statements about X are considered to be the “truth about X.” From this truth about X, we have developed Y, in similar ways, and in response to X. The discourses that constitute X are in constant dialogue with the discourses that constitute Y.

Whether we are talking about pathology as X, therapeutic practice as Y, or any other socially constructed system, we must recognize first and foremost that power is required in order to give X or Y the validity of truth. The authority of science, metrics, texts, experimental methods, and rigid observation is thought to be the means by which we can say with certainty that X is indeed a thing in the world and that Y is the best way to address it. This is all well and good until we really consider the role of power. Power is political. Power is not a scientific reality, power is the arrangement of reality in and around specific human interests. Thus the very nature of truth, is a political, rather than scientific occurrence.

Why do we construct one thing as pathology and another as non-pathology? Is it really about health?

Surely centering oneself and one’s identity through an activity of buying and selling specific numbers on a computer screen as a 60-hour-a-week profession is not healthy. Surely being put in a small concrete cage for years of one’s life is not healthy. Surely living a life that is defined by the constant struggle to sell one’s energy and secure the medium of exchange (money) necessary to support one’s own biological function is not necessarily healthy. So whether I am a Wall Street banker, a prisoner, or an average consumer, my life is not centered on health. Health is a secondary concern at best. Success, punishment, and market participation all take precedence over health for each of these examples. So is it really about health? When we seek to restore someone who has been deemed pathological, what are we seeking to restore them to? And are our efforts at restoration really about placing the person in a position to be healthy?

Furthermore, who benefits (politically) when a portion of our population is considered to be pathological because they engage in the autocratic manipulation of their own biochemistry? When they interact with unregulated illicit markets that are international networks? Who profits? Who gets to be in control? Whose authority becomes the source of truth? Who has a job because of the way we define substance use, and who is considered unemployable? Who gets to survive, and who dies? Whose life gets placed in suspension? Why might we view such a person and their behavior negatively? Who told us this was “bad”? Where did we learn this, and why do we accept it as unassailable truth?

Complicating the Picture

Now that we have kicked the walls out and opened up some intellectual space, we see that we can do this with any form of knowledge that defines various aspects of reality. I mean, are the suburbs really ideal living? Why do we accept sitting in traffic as if it is normal for individual humans to sit in steel boxes for hours a week? Are we really meant to be paired in monogamous relations for decades? Does a dollar really have any value? We can do this to an infinite degree. But what is important about this skill is that it allows us the necessary space for critique to actually enter into the discussion. By complicating the ideas we take for granted, by questioning forms of truth we assume to be real, we allow ourselves the possibility of seeing the world in a new way.

In my perusals of social media, I see criticism often without this capacity. For example, “safe supply is the only answer to the opioid crisis.”…”One size fits all treatment doesn’t work”…. “Abstinence isn’t for everyone”… “Drug users are stigmatized”…”The war on drugs is racist.” We have all heard these statements and arguments. There are certain statements and ideas which precede these comments, and there are specific implications to which these statements are aimed. However, these are not critiques. The way I view these statements are that they are similar to loose tiles in a large mosaic. They are points of instability within the larger picture of how we view, define, rationalize, and treat the use of substances in our western society. They promote questions, raise interesting and necessary points for concern, and they are valuable. They are also very preliminary in the process of critique.

So, what is critique? Or rather, how should we critique this field, this mosaic in which we all live and breathe? Well, by definition critique both identifies power and the expressions of power, while also giving rise to the notion of liberation. You see, critique is a liberatory effort. It seeks to free the subject from the ensnarements of power that oppress or otherwise delimit the subject. This subject can be a person, such as a client, but it can also be an idea. There are lots of ideas that never see the light of day precisely because of the way power arranges reality in opposition to those ideas. This is the ruling order of reality, and it is a space defined by forms of power. “The reason we have therapists is that we have a need for them in society,” yet, turn this on its head and things get weird. “The reason we have pathological substance users is that we have a need for them in society.” You see how your mind resists one of these statements but accepts the other. One seems valid, and the other seems like a stretch or falsehood, almost conspiratorial. If someone suggests our society requires a certain amount of people to live in poverty, or in prison, we struggle to get away from that idea. But if we say that doctors, politicians, and bankers are needed for society to function, we hop right on board that train. Why?

Part of the issue is that we misunderstand how power functions in our society and even through our own ideas and activities. The other reason is that we have a moral dimension we associate with power. “Police are generally good because they fight crime.” We never really say, “crime is needed to challenge the power of law.” And we almost certainly never consider that crime is invented to create jobs. Yet, crime is the singular rationale for billions of jobs worldwide. They exist because of crime. Yet crime too is a creation of our own constructs, generally defined by those upon whom the crime has a negative impact. You see where this leads. On the one hand, we have an idea that is dominant, on the other we have an idea that is subordinate. Inside of those ideas we place people, like the police, who are “good” and the criminal, who is “bad.” These associations in turn ripple out into society, politics, economics, and social institutions until they become what feels like the natural order of things.

Now, onto liberation

Who is kept captive by the normal order of things? Who is excluded? Why? What are the moral assumptions that underly that exclusion? If we take seriously these ideas which challenge the status quo, these loose tiles in the mosaic of substance use disorders, treatment, and care, then we cannot escape the necessity of this question. If we legalize a substance, who is set free? Who or what is now bound and forced to be accepted in this new reality? If legal has nothing to with health or wellness per se, then what is our role? What do we, then, promote? There are always individuals who will be lifted up, and others who are denied when we rearrange systems and ideas. Health, happiness, and resources will be gained or lost to specific individuals. The “trick” or the real test is how we respond to the dichotomies that develop when power shifts into new arrangements. This is the point of critique. It is more than criticism. It is about finding and defining practices, systems of knowledge, and expressions of truth that maximize liberation for everyone. It is not about saying one thing is good, and the other is bad. It doesn’t matter what rubric is marshaled to justify the goodness or badness of something. It is about abandoning the need to make something bad so we can treat it in one way, and the need to make something good, so we can treat it in another. The Key? Principles. Or rather, justifying not by diffuse constructs like “health,” “legality,” or “pathology” but through universal principles that are specifically informed by human liberation.

Whoa there… sounds pretty eccentric

Let’s test it out then. Instead of asking if some system of care is “effective” let us ask instead, is it fair? (wrench, meet the works). Right away we see the difference, we see the threat to the status quo such a question poses. Instead of “effective” let us ask if some specific treatment promotes equality. Instead of determining if a treatment is cost-effective, let us instead ask if it is just. Instead of defining our roles as clinicians who promote health and reduce pathology, let us instead define ourselves as people interested in equity. Equity that is not defined as materialism or identity (though these may be part of it) – but as life, as promoting the ability to live, and the provision of that ability to as many as possible. Instead of just questioning treatment modalities, let’s ask these same questions of the law. Is it fair? Does it promote equity? Is it just? Or let’s apply this to the systems we work in. Is our state mental health care system fair? Does it promote equality among all citizens? Does it serve human justice? In short, do the ways we think, act, speak, study, and operate within this giant mosaic really set people free? Or do we ensnare, and limit others with what we do? Are we agents that represent critical values? Do we represent fair systems? Do we abide by laws and professional ethics that are actually shaped through justice?

I think, when given these ideas, we find there is far more work to do. When given these ideas we transcend the argumentative layer between various ideas about how we should see and respond to substance use disorders. And, most importantly, when given these ideas we are confronted, inescapably, by difficult questions that in a lifetime can only be chipped away at. Yet, with such a northern star guiding our practices and ideas, we can at least be assured that we are perpetually striving toward some future reality that pays homage to the human spirit, and life itself. There is no more radical sense of health than the ability to live as well as one can, individually and in cooperation with humanity. And most importantly, we now have an essential rubric by which to judge our own ideas and actions through a critical lens. We will never achieve the ideal, but that is not really what this is about. it is about shifting the elements of existing reality into new and better forms that over time, and with effort, bring into reach just, fair, and equitable ways of living by promoting systems that are true to those principles. Whether we are talking about treatment, or anything else. That is the nature of critique.

IN AN EMERGENCY:

- Are you or someone you know experiencing severe symptoms or in immediate danger? Please seek immediate medical attention by calling 9-1-1 or visiting an Emergency Department. Poison control can be reached at 1-800-222-1222 or www.poison.org.

- Are you or someone you know in crisis? Please call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or visit suicidepreventionlifeline.org/chat. The call or web chat is free and confidential. Trained crisis workers are available 24/7 to help you.

FIND TREATMENT:

- For referrals to substance use and mental health treatment programs, call the SAMHSA National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or visit www.FindTreatment.gov to find a qualified healthcare provider in your area.

- For other personal medical advice, please speak to a qualified health professional. Learn more about finding a doctor or medical facility at www.usa.gov/doctors.

DISCLAIMER:

The emergency and referral resources listed above are available to individuals located in the United States and are not operated by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). NIDA is a biomedical research organization and does not provide personalized medical advice, treatment, counselling, or legal consultation. Information provided by NIDA is not a substitute for professional medical care or legal consultation.

The words treatment, rehab, addiction, and addict pack a powerful punch – sometimes so powerful we feel as though they are taboo or should not be mentioned.

Whether we are the ones seeking treatment, or are family of a loved one needing treatment, the notion of sharing and discussing the topic of addiction is often silenced. Whether due to social tab oos, shame or guilt of not being able to help an addict, or the fear of failure and relapse, there are a multitude of reasons one may stay silent either as an addict or as the addict’s support system.

oos, shame or guilt of not being able to help an addict, or the fear of failure and relapse, there are a multitude of reasons one may stay silent either as an addict or as the addict’s support system.

Staying Silent – The Addict’s Perspective

As an addict, silence can be one of the reasons we found ourselves on this path to begin with. Silence may be a part of our personality, certainly, but it may also be a coping mechanism that has prevented us from properly expressing and confronting emotions and feelings. We push the feelings down and replace them with substances to extinguish them. Silence compounds the issue, leaving us feeling isolated and alone.

Further, silence is detrimental to considering treatment as an option, especially because we have no one to support them. The process of choosing and entering treatment is something to be discussed, shared with others, and evaluated. Silence can cripple us and often keep us from entering a program. Why do we keep quiet when we know we need help? Perhaps we fear we won’t be supported. Perhaps we’ve disappointed so many times we hesitate to even try again. Perhaps we doubt ourselves, and therefore can’t accept anyone else will believe in us.

Staying silent can also be detrimental to us in recovery, when it is absolutely crucial to be open and honest. Treatment programs are designed to peel away the layers that have shrouded the addict and drowned us in emotional, social, and sometimes physical scars. By opening up – something very new for those in treatment — and sharing sometimes uncomfortable thoughts and feelings, we receive feedback from our support systems that we can implement outside of the program. This feedback is a crucial building block of recovery.

Lastly, silence can be destructive after treatment when we don’t know how to ask for help, even when we realize we need it. The path to recovery can be a lonely one – if we choose – especially if we have become used to not sharing. The complexities of addicted life are ongoing. Leaving treatment does not mean we can again become silent, going back to not sharing our journey, not sharing that we are sober. Being open about where we have been and proud of the work it took to rebuild not only changes us and moves us forward, but can begin to rebuild the relationships that crumbled under the weight of our past choices and behaviors. Support groups and aftercare programs, meetings and sponsors are all in place for a reason – so that we no longer have to live alone in silence.

Staying Silent – The Family Perspective

In addition to the addict, silence can harm their families and loved ones. It is common that an entire family will know or at least believe that a family member is addicted to substances of abuse. They will enable, excuse, and cover-up the addictive behaviors, thinking that somehow this approach normalizes the family relationship, or worse – convinces them the addiction is not real.

Further complicating the problem of staying silent is the guilt and pain caused when the family does not intervene as they see their loved one take the path of self-destruction. While not all addicts are willing to enter a treatment program, they’re secretly suffering in silence, needing the encouragement and understanding from someone willing to support them in taking that first step.

Silence — keeping your privacy and acting as if there’s no problem at all — may seem like an avenue of self-preservation. However, in reality, it can intensify addictive behavior and lead to relapse. Silence does not allow for accountability or responsibility. By opening up and speaking up, allowing others to support you, and asking for help, one begins to break down the walls and continue strong on the road to recovery.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

Alex Colyer realized she really didn’t know about addiction and recovery after losing her best friend Reed McGregor to an overdose in January 2021. To honor Reed’s memory and legacy, Alex started the Albertus Project, a nonprofit organization that is transforming the way the world views addiction.

In this podcast, Alex talks about:

- Holding old, stigmatized views of addiction—without knowing the truth

- What Reed McGregor meant to so many people around the world

- How the world doesn’t show compassion to people with addictions

- That addiction isn’t who people are, but something they have

- Starting to do research but not finding the answers to her questions

- Turning tragedy into action by founding the Albertus Project

- The goals and values of the organization

- Pulling the Me’s into the conversation

- Giving people a voice with the Humans of Addiction stories

- Learning about SMART and the Family & Friends program

- That money shouldn’t stand in the way of a person’s recovery and the initiatives the Albertus Project have in place to help

- How her views on harm reduction changed with a simple analogy

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 988, https://988lifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

For 28 years, an important part of my professional identity has been “addiction professional.” Over that 28 years, addiction professionals have never been a very harmonious group. There have always been disagreements about things like policy, the best treatment models, credentialing, and many other controversies. Despite these disagreements, I never really questioned whether we all belonged to the same general classification–addiction professionals. We often divided up into different camps within the profession and there was plenty of disagreement, but they felt like disputes internal to a coherent professional category because there was enough agreement about things like the risk of harm associated with alcohol and other drug use, the targets for intervention, and endpoints.

In recent years, I’ve grown increasingly concerned about addiction treatment and policy becoming a front in the culture wars. I still believe there’s truth to that, with one-wayers or self-promoters of various types (12-step, harm reduction, medication) often becoming the loudest and most influential voices in the space.

However, another frame is becoming clearer to me. As we have more engagement from public health, harm reduction, and medical providers, there is a growing number of professionals working with addiction, but not recovery. This is an observation, not criticism. Many of these professionals are doing essential work with very high severity, high chronicity, and high complexity cases for whom, in many cases, the treatment system has no real place for. My contact with them made me realize that they are addiction professionals. I’ve worked as something else, a recovery professional or an addiction and recovery professional or a treatment professional, I suppose.

Further, we also have professionals working in this space whose primary concern is drug use, rather than addiction or recovery. I suppose the proper title for them is something like substance use professional?

None of this is to criticize or rank these areas of practice. They are all necessary. The problem is that too many people in each area seek to delegitimize the others.

There’s plenty of room for disagreement about which interventions make sense in which context, what policy should look like, the nature of addiction, and more.

However, there ought to be broad agreement that we need systems that respond to the needs of people who use drugs, AND respond to the needs of people in addiction, AND offer a pathway to full, stable recovery. And, we shouldn’t sacrifice one for another. And, the system ought to be responsive to changes in needs and preferences. And, directionally, it ought to recognize flourishing as the ideal.

Once we agree on that, we can commence with disagreeing about how integrated that system should be, how specialized the workforce in each should be, etc.

Earlier in this series I covered the origin and early evolution of the Recovery Alliance Initiative, provided a description of the expansion and clarification of our model and methods, and outlined a recipe we uncovered of general similarities among effective sectors. I also described a stretch-goal for our field: attempting from the very start with each person to achieve full remission five years after the last clinical touch.

But how could these models and methods translate into something in real life?

In this post I’ll attempt to answer the question, “What do the practical elements of our Recovery Alliance model consist of and look like?” by concretely sharing our practical perspectives, as follows.

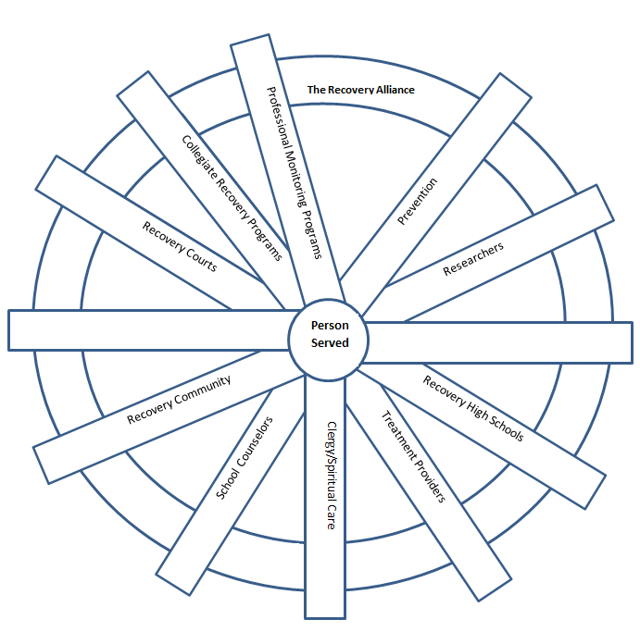

After we had added many more sectors to our original model that only consisted of three, Tom pushed me to make a visual diagram that showed the entire Alliance.

Here you can see the Recovery Alliance from a different perspective.

This simple artwork I created shows the person we serve as central, and the various sectors listed as spokes. We are always careful to keep some spokes blank, with no name written down on them. Why? Keeping some blank is a placeholder for us not knowing everything and for us still learning. In other words, we can add other sectors later that we don’t know about yet.

Further, when we come together as the Alliance in a Summit meeting, we form bonds that hold us together – represented by the wheel around the outside of the circle.

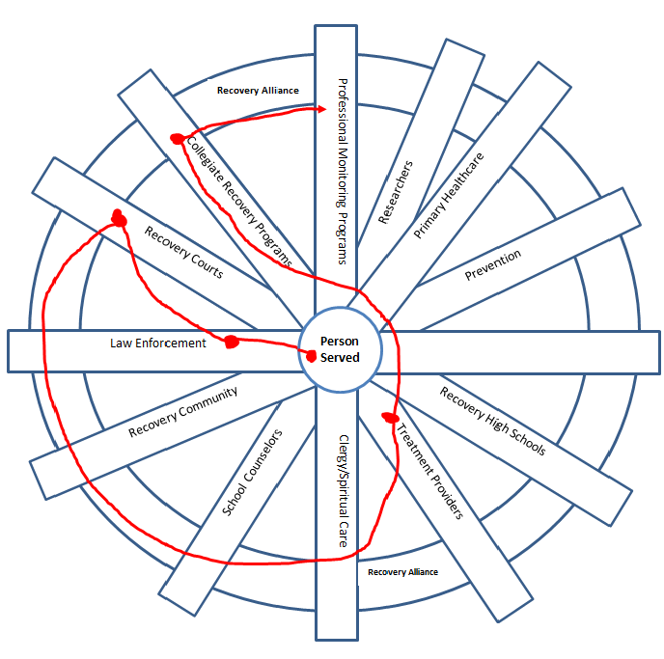

Tom then asked me to provide a visual example of one hypothetical person over time. So, I made this example, pictured below.

Here you can see the journey of an imaginary person who:

- was first arrested by law enforcement

- was next seen to be in need and shepherded into a drug court

- helped clinically by a treatment provider during their time in drug court

- started to imagine a new life such as going to nursing school

- was supported by a collegiate recovery program during nursing school, and

- finally entered professional monitoring when they pursued their license to practice.

All along the way the person was helped proactively with information, support, accountability, and advocacy both before and as their life situation improved and their personal goals unfolded.

Of course, you could make up any number of other examples that would all be very different. And you could adjust the path and particular sectors used with each individual person accordingly.

Next, I’d like to show you two other practical ways to look at this. One is up and down, and the other is across.

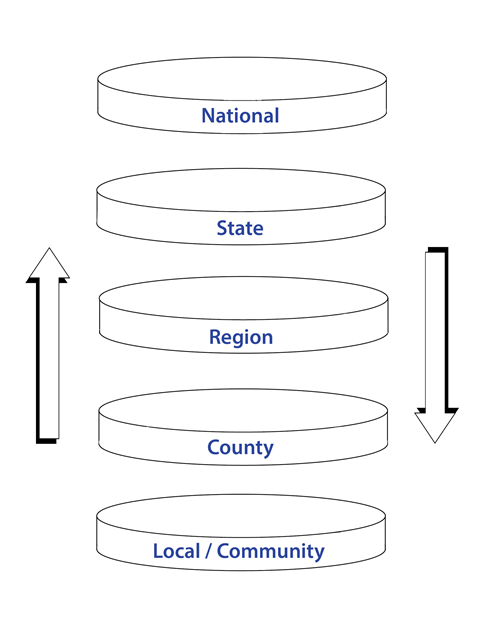

First let’s look at the up and down example using a diagram I made.

Imagine turning that wheel diagram we just looked at on its side. Then copy that diagram vertically a number of times. The result provides a perspective of the opportunity: to move up from the local level, one level at a time, toward the national level, or downward from any given level through specific levels toward the community level.

Here you can see systems like the ones we work in (the spokes) have a local presence but might also sit within a national organization or a national model. This is important to consider because it can help us to slow down and remember that there may be various resources (informational materials, directories, and people, etc.) that are plentifully available.

- We may find useful resources and people that can collaborate with us up and down the scale, and help the person served

- We can also receive and share with others in this way for the sake of system improvement.

Would it be helpful to examine a national directory, speak to a person in a different state, or check for a resource in the person’s local community? Have you done your own homework first to locate available resources, rather than merely assume certain resources don’t exist?

While we do this work in the Alliance we use a few key strategies to remain mindful of the intent of our effort. Toward that end we keep the principles of Behavioral Health Recovery Management (BHRM) in view. Those principles provide us a practical perspective of a different kind.

The BHRM principles are named below. I’ve included a link for a brief resource on the those principles. It is very readable; each principle is described clearly in a short paragraph.

- Recovery Focus

- Empowerment

- De-stigmatization

- Evidence-Based

- Clinical Algorithm

- Apply Technology

- Service Integration

- Recovery Partnership

- Ecology of Recovery

- Monitoring & Support

- Continual Evaluation

Here, I will provide the verbatim statement about the BHRM Principle called a “Recovery Focus”, in case the reader does not know the BHRM principle well and might make assumptions about what it means.

Recovery Focus: Full and partial recoveries from severe behavioral health disorders are living realities evidenced in the lives of hundreds of thousands of individuals in communities throughout the world. Where complete and sustained remission is not attainable, individuals can actively manage these conditions in ways that transcend the limitations of these disorders and allow a fulfilled and contributing life. The BHRM model emphasizes recovery processes over disease processes by affirming the hope of such full and partial recoveries and by emphasizing client strengths and resiliencies rather than client deficits. Recovery re-introduces the notion that any and all life goals are possible for people with severe behavioral health disorders.

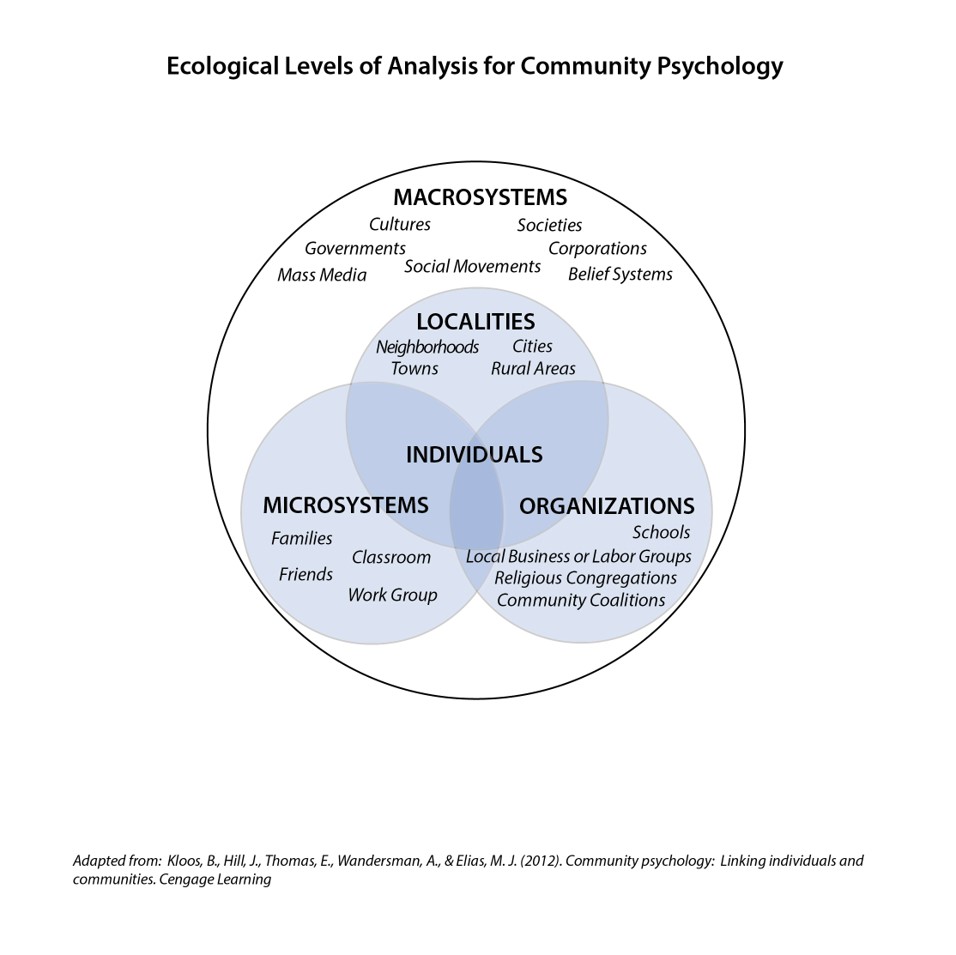

So far in this post I have covered a practical perspective that is vertical. I would like to share another practical perspective I found and brought to our work in the Alliance. This perspective is within or across one of the vertical levels.

If you look at that diagram carefully and really consider it you can see where the person we serve sits within a community.

- Different communities have different kinds of spaces and resources.

- No one person and no one sector can think of everything, or do everything.

So, it’s good to consider the person from this kind of perspective. Adding this perspective may help move us towards being more effective, accessing available resources, and thinking of new and practical collaborations very specifically and locally.

Can we invade our spaces or such community spaces with improved awareness? Can we form collaborations with those serving within these sub-systems? Can we advocate within and for those serving within these macro and micro community resources? What actions can we take or support within these spaces to help the person served?

Struggling with questions like those led Tom (especially) to go further in his thinking and consider macro-level system change. He really did his homework on that topic and found an amazing resource. In the next post I’ll outline the resource he found. It’s a structured method that guides people in effectively making and sustaining large-scale systemic impacts.

What he found really inspired me so I went looking for myself. The next post will also contain the system change resource I found and hbave used routinely in much of my regular work outside the Alliance ever since.

This blog was also published on the NIH Director's Blog on July 11, 2022.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen unprecedented, rapid scientific collaboration, as experts around the world in discrete, previously disconnected fields, have found ways to collaborate to face a common cause. For example, physicists helped respiratory specialists understand how virus particles could spread in air, leading to improved mitigation strategies. Specialists in cardiovascular science, neuroscience, immunology, and other fields are now working together to understand and address Long COVID. Over the past two years, we have also seen remarkable international sharing of epidemiological data and information on effects of vaccines.

Science is increasingly a team activity, which is true for many fields, not just biomedicine. The professional diversity of research teams reflects the increased complexity of the questions science is called upon to answer. This is especially obvious in the study of the brain, which is the most complex system known to us.

The NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative, with the goal of vastly enhancing neuroscience through new technologies, includes research teams with neuroscientists, engineers, mathematicians, physicists, data scientists, ethicists, and more. Nearly half (47 percent) of grant awards have multiple principal investigators.

Besides the BRAIN Initiative, other multi-institute NIH research projects are applying team science to complex research questions, such as those related to neurodevelopment, addiction, and pain. The Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative®, created a team-based research framework to advance promising pain therapeutics quickly to clinical testing.

In the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD ) study, which is led by NIDA in close partnership with NIH’s National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and other NIH institutes, 21 research centers are collecting behavioral, biospecimen, and neuroimaging data from 11,878 children from age 10 through their teens. Teams led by experts in adolescent psychiatry, developmental psychology, and pediatrics interview participants and their families. These experts then gather a battery of health metrics from psychological, cognitive, sociocultural, and physical assessments, including collection and analysis of various kinds of biospecimens (blood, saliva). Further, experts in biophysics gather information on the structure and function of participants’ brains every two years.

A similar study of young children in the first decade of life beginning with the prenatal period, the HEALthy Brain and Child Development (HBCD) study, supported by HEAL, NIDA, and several other NIH institutes and centers, is now underway at 25 research sites across the country. A range of scientific specialists, similar to that in the ABCD study, is involved in this effort. In this case, they are aided by experts in obstetric care and in infant neuroimaging.

For both of these studies, teams of data scientists validate and curate all the information generated and make it available to researchers across the world. This makes it possible to investigate complex questions such as human neurodevelopmental diversity and the effects of genes and social experiences and their relation to mental health. More than half of the publications using ABCD data have been authored by non-ABCD investigators taking advantage of the open-access format.

Yet, institutions that conduct and fund science—including NIH—have been slow to support and reward collaboration. Because authorship and funding are so important in tenure and promotion decisions at universities, for example, an individual’s contribution to larger, multi-investigator projects on which they may not be the grantee or lead author on a study publication may carry less weight.

For this reason, early-career scientists may be particularly reluctant to collaborate on team projects. Among the recommendations of a 2015 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report, Enhancing the Effectiveness of Team Science , was that universities and other institutions should find effective ways to give credit for team-based work to assist promotion and tenure committees.

The strongest teams will be diverse in other respects, not just scientific expertise. Besides more actively fostering productive collaborations across disciplines, NIH is making a more concerted effort to promote racial equity and inclusivity in our research workforce, both through the NIH UNITE Initiative and through Institute-specific initiatives like NIDA’s Racial Equity Initiative.

To promote diversity, inclusivity, and accessibility in research, the BRAIN Initiative recently added a requirement in most of its funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) that has applicants include a Plan for Enhancing Diverse Perspectives (PEDP) in the proposed research. The PEDPs are evaluated and scored during the peer review as part of the holistic considerations used to inform funding decisions. These long-overdue measures will not only ensure that NIH-funded science is more diverse, but they are also important steps toward studying and addressing social determinants of health and the health disparities that exist for so many conditions.

Increasingly, scientific discovery is as much about exploring new connections between different kinds of researchers as it is about finding new relationships among different kinds of scientific databases. The challenges before us are great—ending the COVID pandemic, finding a solution to the addiction and overdose crisis, and so many others—and increased collaboration between scientists will give us the greatest chance to successfully overcome these challenges.

Links: