“Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit — in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.” – Garrett Hardin

I would add to the quote above that we cannot sustain common ground without a sense of shared responsibility to each other, good stewardship, and a lot of hard work. The most effective efforts in the addiction recovery space in the immediately preceding generations has occurred when our community has come together, identified common ground, protected, and nurtured it together. A “we” orientation rather than an “I” orientation.

Twenty years ago, this occurred because the very treatment system that was developed by the recovery community becoming overly focused on profits without a focus on the needs of the community served. The work of treatment became isolated from the very people it was intended to support.

An analogous example of this in agrarian communities is the common grazing lands. A place in which everyone can nurture their livestock and provide sustenance for all their families. Communities feeding themselves through their own effort on their own land. Working collaboratively to ensure that everyone it taken care of, together.

Such ground can only remain viable if it is protected and nurtured by and for the community. Land is sensitive, it can be polluted or overgrazed by members of the community or those external to the community who may not care if its long-term viability is depleted. There is an inherent dilemma. The nurturing of the common ground is neglected, and the land degrades. The tragedy of the commons. We must remain every vigilant about such dynamics and ask ourselves what we are doing to ensure we have sustainable common ground to ensure our long-term common welfare.

There can be powerful individual incentives to use these common grounds for personal gain and to neglect the stewardship necessary for its upkeep. This can maximize the benefit for each individual using the land over the short term at the long-term expense to the entire community. It sets up a dynamic in which people end up competing to get the most right now at the expense of the whole community in the future.

It is in each individual’s interest to take the most from the land but invest less back into what may benefit their neighbor. Such land can be very attractive to other communities wishing for additional pastures. Outside groups may not even care if harm is done to the community as this is not their concern. This dynamic tends to lead to an environment that over time becomes unable to sustain any of those dependent on it for their own needs.

It seems clear that it is easier to nurture common goals when all members are equally without sustenance. Looking back at our own recovery community history, when conditions became particularly unsupportive of recovery nationally, people came together to till the soil and create the rich loam needed for us all to grow. What are we doing to sustain our common ground, and how much have we focused on our collective responsibility for our common welfare?

One of the things I noted in collecting histories from key persons involved in the organizing of the first national recovery meeting in America, in October of 2001 was that several of those interviewed noted that in hindsight, they had wished they had invested more time in working on a recovery plank that would resonate deeply across the entire recovery community. This would have created a deeper reservoir of support.

This was not done, but in their defense, they were mostly a group of people with a lot of aspirations and very few resources. The goals that these visionaries developed by working together over twenty years ago have been achieved to the degree that has transformed how we think about recovery and the ways that we support persons with substance use disorders. As a result of their concerted efforts over many years, we now have several national recovery community organizations a few dozen statewide recovery community organizations and a lot of related types of recovery community affiliates across the nation. Yet, we do not have a short list of things we all think are worth our focus.

Can we sustain and build on the ground those who came before us gave us? How do we do so?

We need to examine what are common ground has been historically and work to adapt or change our focus for our current times while working to keep our soil viable or we will all eventually lose. We will be defined by others, our ideas and contributions subsumed within other groups agendas in ways that may not be consistent with our common goals. We will then have to build everything over again, which we can avoid through good stewardship now.

In 2007, Phil Valentine, William White and Pat Taylor wrote a piece titled The Recovery Community Organization: Towards a Working Definition and Description. Their work was widely accepted by the recovery community. They noted there are three core elements of a recovery community organization. Recovery vision, authenticity of voice and Independence. As recovery communities have evolved, a lot of what we now do operated by treatment systems or local governments. RCOs at times pushed aside by more powerful interest groups seeking to use the valuable resources of the community for other purposes. There was some utility in evolving, but we have to ask if we are losing something of value, and is what was done worth it? Good stewardship would require us to regularly ask questions like this and listen carefully to what we hear back. We must be careful to protect our common ground.

These newer variants of recovery community are often not independent, may not have a recovery focused vision and may not center on recovery representation and authenticity of voice as they are discrete services nestled into entities with other goals. The vision that those pioneers had in 2007 was one in which embraced the capacity of communities to heal themselves. As I noted, they included independence as a core element:

“Independence: We believe that an RCO is most credible and effective as a standalone entity. The leading RCOs are open to multiple levels of collaboration with a wide variety of other organizations, but they are not under the control of an organization that may have conflicting interests. For example, RCOs may work closely with, but are independent of addiction treatment providers. The RCO’s real strength is drawn not from its links to other service organizations but from the authentic voice of the individuals in the recovery community who relate to and actively support it. An RCO serves as a bridge between diverse communities of recovery, the addiction treatment community, governmental agencies, the criminal justice system, the larger network of health and human services providers and systems and the broader recovery support resources of the extended community (e.g., recovery-conducive housing, education, employment, and leisure).”

The Recovery Community Organization: Towards a Working Definition and Description (2007)

Valentine, P. White, W., Taylor , P.

Independence is an important core element. When we move away from the unique role of RCOs as an independent entity to engage the community in its own healing, we risk having services being developed in ways that do not meet the needs of our communities. We move away from the powerful dynamic of communities working to heal their own members and instead towards units of care provided to people as a service by an outside entity. We become recipients instead of central actors in our own community wellness processes.

Stigma in all its subtly can play a profound role in moving us away from the core element of independence. It is so strong even in our allies. There is an inherent tendency to become paternalistic in ways that reduces the role and function of recovery community. There is a gradually shift towards a treatment orientation. The services becoming over professionalized and more consistent with models in which people in recovery are passive recipients of care.

We are also vulnerable to stigma. It is so pervasive. Our own internalized stigma can lead us to doubt our own capacity to heal. Stigma is that deeply woven into our entire system. We then become patients and consumers being served as this is the prevailing service delivery system orientation. The shift can happen so slowly and imperceptibly that it may be hard to detect in the short term. Stigma is infused the very water in which we swim in and the air we breathe. It can kill us. History shows us this. It is much like that proverbial frog in a pot of water slowly brought to a boil until we cannot move and we become some other groups meal.

So, I ask again:

- Are we serving as good stewards in our collective responsibility to the recovery community?

- Do we have deeply understood common goals that affirm the role of community to heal itself?

- What are the goals moving forward those members of our community can agree to being worthy of tilling our collective soil?

If we do not answer these questions, even those who seem to have less need to invest in our common ground in the short term will be harmed as our national recovery community is undermined.

Let’s work together to ask the questions, listen to the answers and to be good stewards for the benefit of all our communities!

Shifting Paradigms. New Opportunities.

Saturday, October 22, 2022

Join the Delaware/District of Columbia/Maryland Region of SMART Recovery for the 6th Annual SMART Recovery East Coast Conference: Shifting Paradigms. New Opportunities.

The recovery community is shifting to new kinds of intervention, treatment, and aftercare. These are based on harm reduction, partial decriminalization, broader mutual support options, and Medically Assisted Treatment. In short: Meeting people where they are. SMART Recovery is at the forefront of this evolution.

This year’s speakers include:

Science writer and author Maia Szalavitz, whose books include Born for Love: Why Empathy Is Essential–and Endangered; Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction – and Undoing Drugs: The Untold Story of Harm Reduction and the Future of Addiction. Maia’s presentation will emphasize the latest in harm reduction and how the Federal government and most treatment providers have embraced the view that treatment and care should be available as widely as possible, and focus on the clients’ goals and objectives.

J. Gregory Hobelmann, M.D., M.P.H., Co-CEO & President of Ashley Addiction Treatment in Havre de Grace, MD, whose presentation will focus on stigma and the best ways to minimize if not remove that altogether in treatment and care (from professionals, peers and family members).

Teri Burns, LCPC, of Columbia, MD – who will present on the relationship of trauma to substance use disorders, and the best practices for addressing both, in the treatment and peer support contexts.

Conference Details:

*Prices increase September 23rd*

Treatment professionals will earn six continuing education credits.

The educational content of the conference has been endorsed by NAADAC and approved by the Maryland Department of Professional Counselors and Therapists (Category A), which will be honored by many other states.

Questions, contact David Koss, conference coordinator, at [email protected]

Thank you to the sponsors:

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

“I never knew that rehab was available to guys like me”, he said to me just before he completed his rehab programme. He’d been in and out of` treatment for many years before he got to rehab. “Why did nobody tell me?” I was left struggling for an answer.

This is one of the things that still upsets me in my work with patients. It is still happening – even in my area where there are clearly established pathways to rehab with no funding barriers to navigate.

Across Scotland, patients with alcohol use disorders sometimes tell of multiple detoxes over time and interventions that focus heavily on prescribed medication at the expense of meaningful psychological and social interventions. Some have never been connected to other people in recovery.

I am particularly saddened to hear again and again that rehab has not been discussed or offered. Some of those on medications for opioid substitution treatment talk of their goal of being prescription drug free, but recount how they have been discouraged or thwarted from moving towards this. Sometimes it is more by luck or initiative by the individual than design that the favoured few make it to rehab as illustrated in the recent lived-experience study on rehab in Scotland:

Another guy that I was selling part of my methadone to said that he was speaking to his addiction worker about getting into rehab. I never actually even knew of rehabs until the guy mentioned it to me. It was just by a fleeting conversation and then I asked that my addiction worker, who was from the community addiction team and it was then that they started speaking to me about rehabs.

Barry, 41

Choice

Darren McGarvey the Scottish broadcaster, writer, and campaigner’s stimulating and emotionally engaging ‘Addictions’ series touches on this. A colleague – an addiction specialist – being interviewed by McGarvey expressed concerns about the phrase ‘parked on methadone’. I found myself nodding – I don’t like it either. It trivialises the valuable support and care that professionals invest in their clients and patients, the relationships that develop and the positive gains individuals make on medication assisted treatment (MAT).

My colleague did accept though that we needed to do better with the psychosocial interventions that ought to go with medical approaches. While there is much to celebrate in addiction treatment delivery, it’s sadly true that not all services provide a high level of care. This is an area for development. But there is something else often missing and that is the connection between community treatment services and residential rehabilitation. That conduit is a bit of a rickety rope bridge in places and an abstruse abyss in others, as the recent data on rehab referrals show.

The phrase ‘parked on methadone’ cannot be easily dismissed when it is used by patients – when it is part of the lived-experience narrative. I am thinking of those past patients of mine who were prescribed it for many years who are now in long term abstinent recovery – those who wish they had been offered a different option earlier. To be clear, I’m not thinking of those who had meaningful interventions, had support with symptoms related to past trauma and who have a good quality of life.

No, I’m thinking of those individuals who once got a ‘script and a pat on the back’, but who treasure the quality of life they now have – something they wish they had reached for sooner. They didn’t reach because they didn’t know they could. And sadly, some of those who looked after them did not know they could either.

Menus

So, if my experience of those coming to residential treatment is anything to go by, we need to do better with our menu of options. I’ve written about this before. In Scotland we are undergoing a roll-out of the MAT standards. These have worthy aspirations to help to improve access, quality, and choice in addiction treatment. However they do seem to be disconnected from treatments outside of MAT, like rehab.

Optimising the use of Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) will ensure that people have immediate access to the treatment they need with a range of options and the right to make informed choices.

Mat Standards

The standards warn of the “high risk of severe drug-related harm, including death” on exiting residential settings (including rehab), despite little evidence in Scotland that this is the case, or acknowledging that there are ways to mitigate risks. Can the MAT standards really help people make informed choices when residential services are painted in such a dark light? The menu, ostensibly extending choice, seems to remain unnecessarily limiting.

And what of the ‘high risk of severe… harm’? Let’s face it, a significant number of people that we admit into residential rehab are already at very high risk of death in any case – it’s one of the reasons they have been referred. Sometimes they get to rehab because all other options have been exhausted – in those cases, it has become the choice of last resort.

Lack of choice is not an issue really if those in our services all want the same things from treatment and treatment is aligned to those goals. But these things are not lined up. Vital public health imperatives drive us to use evidence-based treatments to reduce harms – including death – but these offerings can be at odds with, or fall short of, what individuals and their families want. This is not about valuing one kind of treatment above another – it’s about having a range of treatments available and, crucially, accessible.

In general, it is fair to say that SUs [service users] look for tough criteria to define ‘being better’ – perhaps tougher than their practitioners.

Thurgood and colleagues

Troubling mismatches

Again, I’ve written about this before (here) and it’s a theme I keep coming back to because the problems of mismatch persist. We do not have a joined-up system of care, despite this being a policy priority over many years now.

A study from Berlin[1] found a striking discrepancy between the patients’ desire and staff members’ assessment of the patients’ desire to end opioid maintenance therapy (OMT) in the long term. The large majority of patients reported the aspiration to stop OMT in time, whereas only a minority of staff members believe that their patients might really have such a desire.

When these kinds of findings are reported (there are many studies identifying this theme) a common response is ‘of course patients are going to say that – diabetic patients would like not to have to take insulin, but they must because it keeps them alive’. Methadone is not insulin. People do choose to move on from opioid substitution and plenty of them achieve it – though of course there are hazards. People need to be able to move rapidly back to MAT if return to use occurs.

Treatment is not intrinsically built on that premise of choice though. Treatment is predicated on what large scale research says is good for groups of people with opioid use disorder. It therefore sometimes misses out on what’s important or best for the individual.

An interesting piece of research from Canada[2] explores this issue. By analysing existing qualitative research (research which teases out people’s feelings and thoughts – seeking to identify how they experience the world), the authors wanted to find out what individuals receiving medication for opioid use disorder – drugs like methadone and buprenorphine – expected to get from treatment.

They found that patients set some goals that were not considered as ‘markers of treatment effectiveness’ – in other words goals that were important to them as patients, but not seen as particularly relevant to the clinicians treating them. A mismatch in effect.

Darren McGarvey has a view[3] on the reason for this mismatch:

“One of the biggest problems we have culturally is this cross-institutional misunderstanding of addiction as ultimately being a choice, which has led to a drug support infrastructure which is often misaligned with the needs of problem users.”

McGarvey,

Clashes

According to this review, what do patients want from treatment and where are the clashes? One goal that providers prioritise is retention in treatment – keeping people engaged over prolonged periods – but this is apparently not rated by patients. In a study in 2020, researchers asked the open-ended question of what patients’ desired targets in treatment are. Only 4% of participants responded that they wanted no change from their current treatment. In another study, fewer than one in five wanted to remain on methadone.

In another study, almost three quarters wanted to improve their physical health while other aspirations they identified included: having a ‘normal life’, improving mental health, having a job, raising a family and getting a decent place to live. This chimes with me. These are exactly the sorts of things that patients tell me they want from treatment. They are however not routinely measured in treatment settings.

| What patients want from treatment A ‘normal life’ Good physical health Good mental health A jobA family A place to live |

What do the researchers conclude?

One of the biggest obstacles when creating and providing an intervention for patients with chronic conditions like opioid use disorder (OUD) is to identify what is being achieved by the treatment being implemented and for whom is it being delivered. The current treatments being used for OUD patients are not systematically tailored to the patients’ goals but instead investigate objective measures like urine drug screen or treatment retention, which also have a place. However, consideration for other aspects of treatment goals should be included.

Reflections

I think people deserve informed choices in treatment where their goals are clearly identified and then we are honest about how the treatments on offer may align to those goals. For some people being in medication assisted treatment will be a good fit, but for others their goals may be better met in other treatment options. Needs and progress/regress are dynamic, so there is a need for treatment options to have open connections and several alternatives over time.

There is accumulating evidence that those other options are limited, or frustratingly – despite efforts to change this, effectively not available at all. The saddest thing is when we, as treatment professionals, end up being the barriers that prevent our clients and patients getting to where they want to go.

In the work I’ve been involved with for the Scottish Government’s Residential Rehabilitation Team, we have found evidence of poor availability of residential treatment options with many roadblocks in place. Despite the Scottish Government shining a spotlight on the issue, setting clear goals, and increasing the resource available, some of these barriers are proving very challenging to dismantle – disappointingly, at times, down to people or groups in positions of power, or a failure of prioritisation in local health and social care partnerships – resulting in a persistently pernicious postcode lottery.

That needs to change if we are to posit our services as patient-centred, offering a broad menu, trauma-informed, involving a whole family approach, and underpinned by shared decision making. It is important that our treatment offer both reduces harms and aligns to the aspirations of patients and their families, focussing on quality of life as well as quantity of life. While there are some signs of improvement, we still clearly have a distance to go.

Continue the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

[1] Gutwinski S, Bald LK, Gallinat J, Heinz A, Bermpohl F. Why do patients stay in opioid maintenance treatment? Subst Use Misuse. 2014 May;49(6):694-9.

[2] Sanger, N., Panesar, B., Dennis, M., Rosic, T., Rodrigues, M., Lovell, E., Yang, S., Butt, M., Thabane, L., & Samaan, Z. (2022). The Inclusion of Patients’ Reported Outcomes to Inform Treatment Effectiveness Measures in Opioid Use Disorder. A Systematic Review. Patient related outcome measures, 13, 113–130. https://doi.org/10.2147/PROM.S297699

[3] McGarvie, D. (2022) The Social Distance Between Us: How Remote Politics Wrecked Britain, Ebury Press, pp 126-127

In the first two posts of this series, I initially described the origin and early evolution of what we call the Recovery Alliance Initiative. Those posts were followed by one that described the expansion and clarification of our model and methods within the Alliance effort.

In this post I’ll describe a by-product of our effort up to that point – a recipe we uncovered.

Our effort up to that point included years of planning and holding Summit meetings, as well as my own personal reading and study related to the systems we were involving. Our effort also included lots of very focused and sustained conversations between Tom and me about our intent and methods, each sector specifically, and all the sectors together. I started to notice that certain “ingredients” kept showing up across different sectors or through the time of the lived experience of the one being served. And I started to develop the notion that if or when combined these ingredients seemed to be powerful and effective, in general.

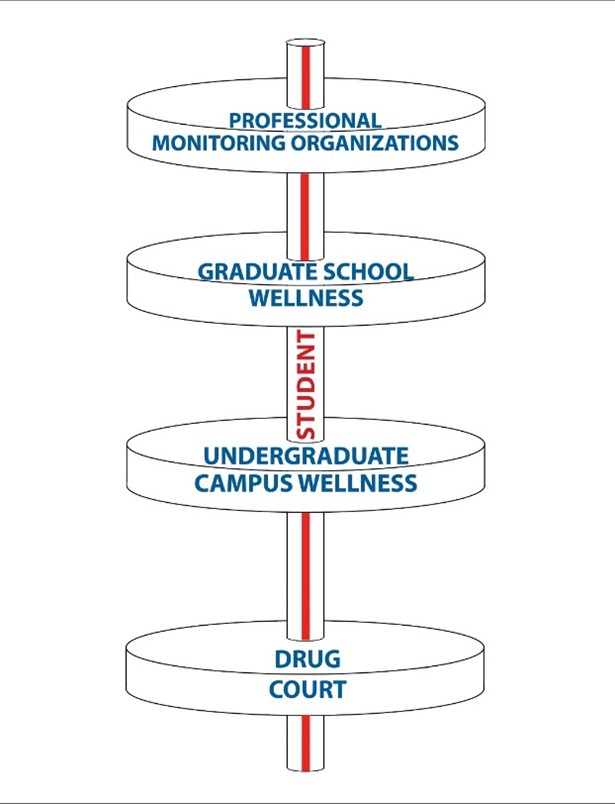

To help elucidate this, there are three sectors in our Alliance that I want to highlight. (By the way, I want to point out that these three sectors serve special populations that are quite different, assist those commonly thought of as supposedly hard to help, and yet are known as being effective). Here are the three sectors:

- Collegiate recovery programs

- Professional monitoring organizations

- Drug Court also known as Recovery Court; Veteran Court.

Eventually I came to realize that these three systems have some structural and functional similarities, and that realization became very interesting to me. All three of them:

- take the long view

- use a multi-year structure

- work in the natural or indigenous environment

- see the family as central rather than peripheral

- work with person-centered goals, and use contingency management.

I have come to see these as an important combination of ingredients. I described my thinking in some detail (Coon, 2015). For those that might be interested, White, Boyle & Loveland (2003) serves as a theoretical and practical substrate to that realization.

But I’ll go even further. These systems seem to at least partially conceptualize and operationalize what has been called initial disease management and later recovery management (for relatively severe, complex, and chronic addiction illness – that is, those to whom it seems to apply) on the path of the person served.

Robert DuPont, MD briefly visited one of our national Summit meetings. In his comments to me Dr. DuPont emphasized the use of eventual full recovery as a starting place in working with people rather than believing without examination or evidence it is not possible for the person we are attempting to help. He emphasized that this stance of eventual full recovery helps push the system, in any modality or sector, to do its absolute best on behalf of the person they serve. Those that might be interested can check out DuPont & Humphreys (2011).

Further though, Dr. DuPont uses Five Year Recovery as the standard of effectiveness (DuPont, Compton, & McLellan, 2015). When Dr. DuPont explained this standard to me, he stated that he means full recovery five-years after the last clinical touch. For example, he described examining the continued favorable outcome for physicians who underwent addiction treatment five years after their five-year professional monitoring had concluded.

Dr. DuPont stated that this standard of full recovery five years after the last clinical touch is relatively new for the care of addiction illness. But he pointed out that it’s the same standard primary healthcare has been using for a long time concerning remission of other chronic serious illnesses, like cancer or heart disease. Starting from that standard of effectiveness pushes the system to do its best, including:

- staying engaged over the much longer term,

- not giving up hope or giving up on helping, and

- stretching the system for the best possible outcome for each individual, and one that will last.

Although a standard of care or benchmark of effectiveness might be a positive aspirational goal for all systems addressing or intersecting with those experiencing severe, complex, and chronic addiction illness, what can we do right now within our existing systems to improve our methods? Over the years, Tom and I have been convinced that one immediate way forward would be to link existing systems in a meaningful way.

- One of those ways is through efforts like our Summit meetings (e.g multi-system working groups formed to tackle change projects that answer needs revealed when siloed sectors meet).

- Another of those ways is to take the long view of the life course of the person served, to consider our systems over the long term from the person’s vantage point, and promote or innovate collaboration from the person’s perspective.

In the next post in this series, I will present concrete practical perspectives that Tom and I have either developed or adopted for the work of the Recovery Alliance.

Addiction to alcohol and other drugs is a disease that impacts both the substance user as well as their entire family network. When we think of recovery, it can be easy to feel that the process is only applicable or crucial for the suffering alcoholic or addict. However, a critical component of combating the disease is the recovery of the family.

Addiction to alcohol and other drugs is a disease that impacts both the substance user as well as their entire family network. When we think of recovery, it can be easy to feel that the process is only applicable or crucial for the suffering alcoholic or addict. However, a critical component of combating the disease is the recovery of the family.

When a loved one is struggling, we may find ourselves in a state of tunnel vision–only focused on the needs, wants and feelings of the one we care about instead of our own. As the disease progresses, the added stress and turmoil continues to build atop our family’s foundation, and if not tended to, our foundation can crumble.

Family recovery begins when we admit and understand that our loved one is powerless over substances and that subsequently, their family life has become unmanageable because of their disease.

As family members, we can gain insight from the 3 C’s of Addiction:

- You did not Cause the addiction

Nothing you did or didn’t do caused your loved one to become chemically dependent.

- You can’t Control the addiction

The alcoholic/addict is the only one who can take responsibility for managing their disease.

- You cannot Cure the addiction

There is no cure for the disease of addiction, only treatment.

Once we understand the 3 C’s, working to improve our own healing can begin.

- You can take Care of yourself

Make time to do the things that are good for you and that make you feel good. Read a book, go for a walk, journal, make a good meal or soak in the bath. Do things that promote your own personal sense of connectivity, health, and well-being.

- You can Communicate your feelings

You are allowed to say how you feel. Addiction is a disease that is often associated with feelings of guilt, sadness, anger, frustration, grief and shame for alcoholics, addicts, and their family members. Own your truth and be honest, be direct and specific when sharing your feelings.

- You can Celebrate who you are

Remind yourself of the things that are special about you, your hobbies, your passions, your goals. Do not lose sight of these aspects of your identity. Addiction can blur many lines in the family system, allowing us to lose sight of where our loved one ends and we as individuals begin. Our identity can become so wrapped up in caring for another individual that we often lose sight of ourselves. By celebrating our individuality, our uniqueness, we are reminded of who we truly are and our purpose outside of the realm of the disease.

Set aside time to heal

Addiction is a war of attrition at times. It can be time consuming and exhausting. Once a family member has agreed to accept treatment, it is easy to feel as though the work is done.

“I’ve already missed so much work/school/social activity and am so behind in life because of this disease I don’t have the time to try and heal myself!” You deserve to heal. You deserve to guiltlessly prioritize yourself and work through the trauma that addiction can cause.

Set boundaries

Boundaries are an important component of family recovery. Boundaries provide us with a sense of individuality and allow us to own our feelings, our experiences and our problems. They also provide a sense of contentment and peace with the self and allow the family to work to not personalize the addict’s problems. To set healthy boundaries, the family must learn to detach with love. Detaching with love does not mean to shutout or isolate the loved one. It means to detach oneself from the disease

Release guilt, shame, blame

Addiction is a disease that feeds on the power of dark and all-consuming emotions. Guilt, shame and blame often draw us inward and leave us unwilling to reach out for the support that is so incredibly important when a family is in recovery. Work to release these emotions as you focus on the positives of the journey ahead.

Find your support system (NAR/AL ANON), ask for help, and rely on these support systems

Again, the way to heal is to make the time to do so. Prioritize yourself and your sanity and seek out support through groups such as NAR/AL ANON family group meetings. For help finding your local group, please call one of the phone numbers listed below:

Al-Anon and Alateen Family Groups

Phone Number: 1-888-4525-2666

Nar-Anon Family Group

Phone Number: 1-800-477-6291

Forgive yourself and focus on today

Unfortunately, you cannot change or undo the past. Move forward with confidence regarding what you can control. Focus on what is directly in front of you. Ask yourself, what do I need to accomplish today to be well?

Recovery is not an event, but instead an ongoing, evergreen process.

Family members can also relapse in a sense. We may relapse into old unhealthy behaviors or ways of thinking. The key to healing is understanding that recovery is not an event, but a process that will always require our attention and the prioritization of our self-care.

Serenity Prayer

Finally, in times of trouble, remember the serenity prayer:

Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

By the time someone reaches out for addiction care, they may have already have suffered numerous painful losses in their lives. Addiction can steal a person’s happiness, job, friends and family, and can erode their freedom.

Far too often, the expectation is that someone must hit “rock bottom” before treatment can work. But this is a myth that can have dire consequences. By then the damage is consequential and a much harder road to recovery. Factually, the best time to get help is as soon as possible. Yet frequently when a person asks for help early on, society – friends and family, coworkers, health care systems – do not recognize it as a serious issue. They may ignore or deny it.

In a commentary published today in JAMA Psychiatry, Tom McLellan of the Treatment Research Institute, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Director George Koob, and I raise the possibility of moving toward a plan for better detection and support of those in the early stages of substance use disorder that, if untreated, may lead them to develop a severe health condition – addiction.

To define this early stage that we refer to as “pre-addiction,” we propose considering the criteria of mild or moderate substance use disorder (SUD). Identification of “pre-addiction” as an early condition of addiction could motivate greater attention to the risks associated with early-stage substance use disorder and help marshal the policies and healthcare resources that will support preventive and early intervention measures.

We are proposing the term “pre-addiction” because it gives a readily understandable name to a vulnerable period of time in which preventive care could help avert serious consequences of drug use and severe substance use disorders. This is akin to how we counsel and provide for care to prevent chronic diseases like heart disease or diabetes for patients who demonstrate higher risk of developing those conditions.

Healthcare in the U.S. is notoriously bad at delivering preventive medicine. Despite the well-known conventional wisdom that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, the system has always been set up to treat diseases and disorders once they manifest, not avert them. This has started to change for some conditions, however. For instance, it is now standard to monitor risk factors like cholesterol, blood pressure, and BMI during routine checkups, so that steps can be taken to avert heart attacks or stroke through some combination of lifestyle changes and medications.

The same mentality could be applied to substance use disorders. It is no longer necessary or reasonable to make people with drug or alcohol problems “hit rock bottom” before a substance use disorder is recognized and addressed. Nor is it true that people will only contemplate treatment when their disorder reaches that point. It is possible, through screening and early intervention—including brief intervention during routine checkups—to alert people to problematic patterns of drug or alcohol use that do not (yet) meet the threshold of addiction, sometimes defined as severe substance use disorder.

One of the definitions of addiction is inability to control drug use despite adverse health consequences and even despite a desire to change. For those meeting the criteria of severe substance use disorder, treatment and external recovery supports are often needed. Unfortunately, just 10 percent of people who could benefit from treatment get it. Prior to reaching this point, however, it is easier for people to exert control, including by setting limits and being more mindful of their substance use.

Increased awareness of the harms of heavy drinking and binge drinking even outside of a diagnosed alcohol use disorder, for instance, has alerted people to unhealthy patterns that in an earlier era escaped attention because the crucial addiction criterion—inability to control use—was not met. A diagnosis of pre-addiction could similarly serve as an alert to the individual about a behavioral pattern with potentially major—but also very preventable—health and life consequences down the road. It could create a different inflection point, one that recruits the patient more actively as an agent in their own health and wellness.

It could also save lives. Today’s extremely hazardous drug landscape is dominated by fentanyl, which is increasingly contaminating or being sold in place of non-opioid drugs. Even people who only take drugs occasionally, and even people who do not knowingly take opioids, run the risk of a fatal overdose. Some lever is needed to enable routine healthcare to serve as a screening and teaching opportunity about the danger of drug contamination that people who use illicit drugs face, even those who only use them occasionally.

For a renaming of mild to moderate substance use disorders as pre-addiction to be meaningful, it would require measures to define and detect substance use that is clinically significant and amenable for early intervention. Existing DSM criteria for mild to moderate substance use disorder are a starting point, as are existing screening tools used in primary care that ask about frequency of substance use. But research is needed to better characterize the kinds of substance use and the kinds of individual risk factors that would raise concern for future addiction and other health problems.

There is a need for a wider range of evidence-supported and reimbursable interventions for individuals meeting pre-addiction criteria, and clinicians would need to know how to deliver them or refer patients to the appropriate specialists. NIDA is already directing substantial funding, including via the Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative®, to increase the range of addiction treatments, but a diagnostic framing of mild to moderate substance use disorder as pre-addiction could create a market and thus incentive for greater development of interventions to prevent addiction from developing in the first place. This could potentially even include devices and over-the-counter aids that people could use on their own initiative without a doctor’s supervision.

A concept of pre-addiction would also require—but in turn could facilitate—greater public and clinical advocacy about addiction and how it develops. Currently the genetic and behavioral risk factors for diabetes are well-known, as are the clinical indicators of “pre-diabetes,” which can facilitate early intervention. Greatly needed is improved training in medical schools for recognizing and addressing all levels of substance use disorder, including low-severity substance use disorder that is nevertheless a risk for becoming more severe.

There are many questions, however, and such a paradigm change requires hearing multiple perspectives and diverse voices. We want to hear from the public, including people with lived experience, and from clinicians about the potential advantages as well as drawbacks of a pre-addiction framing. Above all, it is critical that changes to clinical practice alleviate, rather than exacerbate, harmful stigma.

Rebranding mild to moderate substance use disorder as a common and addressable behavioral health pattern could normalize and thus destigmatize potentially unhealthy substance use that does not merit the specialized interventions required to treat addiction, while also raising awareness of the potential health risks of such a pattern. However, interventions should ensure that the pre-addiction label does not lead to stigmatization of the people to whom it is applied. In particular, this will require legal protection when disclosing drug use to physicians. Unless drug use is decriminalized, fear of disclosure presents an obvious challenge to screening for and medically addressing non-disordered substance use in general medical settings.

Whether it comes with a “rebranding” or sparks renewed thinking, it is important that we understand addiction not as a disease that appears overnight, but as a condition with a backstory: a history of escalating substance-taking, often exacerbated by environmental and personal historical circumstances and by genetic risk factors. A greater awareness of the potential negative trajectories from substance use disorder and opportunities to prevent them will empower those in the early stages of a substance use disorder to arrest its escalation.

Steve Kind of Mankato, Minnesota, is a SMART Facilitator and new SMART employee. His alcohol struggles began in high school and continued into adulthood. After his second DUI, he was about to lose everything, including his wife. Then an open-minded, forward-thinking counselor suggested he look into SMART as a new path to recovery. Now he is living his Life Beyond Addiction.

In this podcast, Steve talks about:

- His struggle with alcohol addiction and the 12-Step recovery process

- How his views on driving under the influence have changed over the years

- Being a defensive Christian and then an Atheist

- Being introduced to SMART and watching a Jonathan von Breton YouTube video

- What came from traveling 70 miles to attend a SMART meeting

- Sitting in a meeting room by himself and waiting for participants

- The word-of-mouth “snowball effect”

- Writing a book about his life: The Inspirational Dissatisfaction

- How a job in California almost cost him everything

- Getting off the couch and changing your life!

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

As Bill White’s page has moved, I updated all the links, fixed typos and placed all of the interviews available as PDFs as well as hyperlinked to the Recovery Review page. Also, I am pleased to note that the training I developed based on this body of work has been academically vetted and is available through the Opioid Response Network in all 50 states and territories.

NRAM 20th Anniversary of Recovery Summit Interviews –

Conducted by William Stauffer

NRAM Interviews:

#1 Bill White – Recovery Historian, researcher, and author of Slaying the Dragon LINK HERE PDF HERE

#2 David Whiters – Founder Recovery Consultants of Altanta Inc. Decatur GA LINK HERE PDF HERE

#3 Carol McDaid – Cofounder McShinn Foundation Principal at Capitol Decisions Inc. LINK HERE PDF HERE

#4 Ben Bass – Executive Director of the Recovery Alliance of El Paso TX LINK HERE PDF HERE

#5 Tom Hill – Senior Advisor SAMHSA and senior advisor White House ONDCP (retired) LINK HERE PDF HERE

#6 Dona Dmitrovic – Senior Advisor Recovery to SAMHSA LINK HERE PDF HERE

#7 Phil Valentine – Exec Dir, Connecticut Community for Addiction Recovery (CCAR) LINK HERE PDF HERE

#8 Johnny Allem – Led Society of Americans for Recovery (SOAR) the first national RCO LINK HERE PDF HERE

#9 Bev Haberle – Exec Dir PRO-ACT of The Council of Southeast PA, Inc (retired) LINK HERE PDF HERE

#10 William Cope Moyers – VP public affairs / community relations Hazelden Betty Ford LINK HERE PDF HERE

#11 H Westley Clark, MD – Dir CSAT SAMHSA US Dep HHS (1998-2014) LINK HERE PDF HERE

#12 Betty Currier – Organized Friends of Recovery of Delaware and Otsego Counties NY LINK HERE PDF HERE

#13 Mark Sanders – Author, curator Museum of African American Addictions, Tx & Rec LINK HERE PDF HERE

#14 Cathy Nugent – First grant officer RCSP – SAMHSA. LINK HERE PDF HERE

#15 John Winslow – Founder, Dri-Dock Recovery Center & International Recovery Day LINK HERE PDF HERE

Information on the New Recovery Advocacy Movement & Related Articles

- FreedomFest 1976: A Celebration of Freedom from Alcohol and Drug Addiction YouTube Link HERE

- Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Tx and Recovery in America. (1998). Bill White Link HERE

- Toward a New Recovery Movement (2000) Bill White Link HERE

- State of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement – Dallas Texas 2013 – Bill White Link HERE

- Recovering substance abusers brave stigma by giving up secrecy – The Washington Post – 10/1/15 Link HERE

- A Day Is Coming: Visions of A New Recovery Advocacy Movement Bill White (2015) Link HERE

- 40 Years Ago the Unthinkable Happened – Greg Williams Link HERE

- Reflections on Recovery Representation – Bill White / Bill Stauffer 2020 – PDF HERE Link HERE

- Personal privacy and public recovery advocacy – Bill White / Bill Stauffer / Danielle Tarino Link HERE

- Online Museum of African American Addictions, Treatment and Recovery – Curator Mark Sanders Link HERE

Links to other documents & videos

- Interview with Harold Hughes in the 1960s Link HERE

- Marty Mann Papers Link HERE

- Rutgers School of Alcoholism History Link HERE

- Catching Up with Bruce Holley Johnson, Ph.D. Link HERE

- The Anonymous People – Operation Understanding Link HERE

- The Anonymous People – Greg Intro Link HERE

- Tom Coderre – Many Faces One Voice Link HERE

- Marty Mann’s Info with Tom Hill and Stacia Murphy Link HERE

- Marty Mann-Two Powerful Speeches Given at High Watch Farm 25th Anniversary of High Watch Link HERE

- AA Speaker Harold Hughes The Governor His Alcoholics Anonymous Talk 1970 Link HERE

- Mercedes McCambridge – Operation Understanding US Congress May, 8th 1976 “Lincoln was Right” Link HERE

Link to this document HERE

Links Updated July 2022

In the first two posts of this series, I described the origin and then the early evolution of what we call the Recovery Alliance Initiative. I encourage you to go back and read those installments before you read this one on the expansion and clarification of our model and methods.

Through our many conversations and sustained effort Tom and I were able to:

- benefit from the lessons of our earlier efforts

- include many more sectors

- become even more action-oriented

- get collaborative work groups going to help address needs closer to the local level of attendees

During our subsequent work in Alliance-related activities we emphasized that in terms of concepts and processes the focus of the Recovery Alliance Initiative is on bringing separate systems together (that are involved in recovery support) for the purposes of:

- Awareness (awareness of each other’s systems, their philosophies and practices, and whom they serve)

- Collaboration (developing working relationships across programs and systems)

- Advocacy (e.g. between systems, on behalf of each other’s systems out to the world, directly for the person served, etc.)

- Action (making changes to better serve people and improve our programs)

We clarified that when we bring systems together to facilitate their interaction, we help them:

- Improve detailed awareness of other systems of recovery advocacy and support;

- Identify opportunities to assist the person served across other systems, over a longer trajectory of time, and across stages of personal transformation (individual recovery);

- Identify needs that could be more successfully addressed by collaboration or combined effort with other systems of recovery advocacy;

- Promote advocacy within, across, and for systems of existing and potential recovery support.

By contrast, at the start of our collaboration in 2013, Tom and I assumed advocacy could begin from inside our field out to the world, on behalf of the individual served. But we eventually realized that advocacy had to start “in-house”. By that I mean we found that advocacy had to be at the level of one sector advocating for itself to the other sectors. Why was that necessary? We found that differing systems within our field didn’t understand each other and when they later did, they struggled to support what they learned.

Those of us helping to drive the Recovery Alliance Initiative recognize that while no single entity or organization has “the” answer to the complex issues surrounding severe substance use problems, many organizations representing many different systems are doing outstanding work within those systems. We recognize that coming together affords us the opportunity to identify ways these systems can better work together, identify gaps, and arrive at improved solutions. And our work toward improving awareness and collaboration has also helped identify needs, opportunities, and projects that remaining siloed would not naturally reveal.

From the time the Recovery Alliance Initiative was started as an idea in 2013 we have learned a few important principles. Here are two of them we have put in the form of quotes:

- “We’re stronger and better together, than we are if we’re siloed.”

- “You don’t have to make others wrong in order to be right.”

Overall, the Alliance works through Summit meetings and bringing about the formation of collaborative working groups.

- During Summit meetings, as conversations unfold, gaps and needs tend to emerge.

- This often results in ideas for projects whose solutions involve multiple sectors in our field.

- When needs are concretized collaborative working groups form with some assistance, take on projects that emerge during our Summit meetings, and sustain that work after the in-person Summit meeting.

- Throughout the course of conversations within the Summit meetings, attendees tend to cross-fertilize knowledge and skill between systems fairly well on their own (attendees tend to be curious, learners, and doers).

I’ll mention here briefly that early in our efforts we built and revised many times a structured project guide for use by table leaders (during the Summit meetings) and project leaders (after and between Summit meetings). Sharing that guide here would be beyond the scope of this writing. But that guide embodies the notion that the work is done in collaborative working groups that sustain their effort outside the meetings until their project is completed or their goal is met.

Producing and revising that project guide also included production of accompanying recorded videos within which we highlight:

- the intent of the Alliance

- the purpose of a particular Summit gathering

- tips for facilitating and guiding table flow

- use of the working group project guide, and

- several of the visual diagrams I’m sharing in this blog series.

Using recorded videos containing instruction and training material, Tom and I have been able to support the work of the Alliance at the convenience of an attendee’s click.

To help anchor the specific intent of collaboration more concretely, Tom has coined three phrases that we incorporated in our methods and materials. Here they are:

- “Just because we get together doesn’t mean we are working together as one.”

- “Just because we work together, doesn’t mean we are in alignment.”

- “Just because we are in alignment, doesn’t mean we are getting it done.”

In terms of expansion over the years, we eventually added members and leaders from additional sectors to the Alliance (beyond Collegiate Recovery Programs, Drug/Recovery Courts, and Professional Monitoring Organizations) including:

- Law Enforcement

- Prevention

- Research

- Spiritual Care/Clergy

- Recovery Community

- Primary Healthcare

- Recovery Schools

You might notice we deliberately de-emphasized addiction treatment per se and any other form of clinically-related SUD-specific services. This has been intentional for a number of reasons.

And yet, another category or system we also have attend are those representing specific kinds of treatment providers, therapists, and healthcare related systems – kinds of specialty care within addiction-related services. These have ranged as widely as whole hospital systems to local harm reduction groups.

We eventually grew to at times also bring in national policy bodies, national advocacy groups, state-operated leadership bodies, and similar policy-related organizations. As with other sectors, we have had them sit down together, begin to share what they do with each other and with the various sectors already in the Alliance, and join in collaborations across systems.

During a Summit meeting when we hear a sector describe exactly what they do to help people it’s usually very eye opening for the attendees. While we recognize the special contributions that are unique to each sector overall, it’s also important for the sectors to be aware of each other at the local, state, and national levels. Personally, I’ve been quite touched while watching and listening to clergy and law enforcement interact.

But what are the basic impacts for most attendees?

- As helpers in our field, we move from basic awareness that a sector exists, to really understanding more exactly the part they play to help people.

- As we listen, we start to know. And by sharing exactly what we do we also become known. In our experience this alone has been powerful.

- After Summit meetings, collaborations or projects across sectors start happening almost on their own.

- But there’s another big impact. We start to see the person we are serving through the lens of other sectors and what those other sectors do, over the long term.

During our efforts over the years, I came to realize certain features inside certain sectors seemed to keep showing up in different sectors or systems in the field. When I would come to realize a feature seemed to be showing up as a theme across sectors, I would add that component to the list of features I was building. I thought of that list as a list of “ingredients”.

Mostly a long, slow, internal processor I memorized the list of ingredients as I moved along. And I have continued to meditate on the list and its meaning over years. To me, these common ingredients seemed to be at least partly responsible for some of the positive impacts across systems of the field and through time for the person.

I’ll describe these ingredients in the next post in the series: a recipe we uncovered.

In the first post in this series, I described concepts connected to the origin and early formation of the Recovery Advocacy Alliance. For the sake of continuity and understanding, I encourage you to go back and read that post if you haven’t done that yet.

This is the second post in the series. In this post I’ll describe the further evolution of the Alliance.

After our initial trading of ideas in 2013 Tom and I formed the Alliance and started to put in effort. That work eventually included holding our first national meeting of sector leaders in 2014. The general purpose of that summit meeting was to assist representatives of collegiate recovery programs and professional monitoring programs in beginning to understand each other’s systems and to collaborate for the sake of the person served.

After that point, however, Tom called me once again with another question. This time he phrased it more as a challenge than a question.

He said, “Give me a reason to put Drug Court at the table.”

As I always do, I asked him for time and “…permission to think…”. This time he declined with good humor and said “No. Just tell me your answer.”

I retorted in the moment by saying, “Drug court doesn’t fit. The answer is that it doesn’t fit. That’s the answer.”

Of course he pressed and said, “But tell me why Drug court does fit.”

I had nothing new to say in that next moment. So, I defaulted and simply said, “It’s the same person again.” Before they went back to school for a life change, they were arrested, and got into Drug Court.”

He accepted that answer and let me off the hook of having to give him a better answer. But he once again asked for a visual diagram.

My reply was to merely replace “Addiction Treatment” with “Drug Court” in the timeline image I had given him before. In truth I liked this visual a little bit better than that first one. Why? Because to me, Drug Courts collectively are more like a true sector within our field (from my clinical perspective) rather than “treatment” which to me seems so broad and varied.

Tom and I held a national summit in 2016. It was fantastic, especially compared to our first national gathering in 2014.

- The attendees had great energy.

- The culture shock and awkwardness from the very different systems meeting for the first time in 2014 was in the past.

- And the attendees were ready for real collaboration.

During our 2016 meeting, while things were rolling along well, one of the attendees said something close to this:

“I think we have representatives from our respective national conferences here in the room. I’m on my own conference planning committee. I think key representatives from each of our systems could speak as a panel at all our national conferences. I’ll commit if others will.”

Within seconds we had all the needed commitments.

Regardless of the good movement forward, around that time I wanted to step back and write something that had a counselor-patient focus. I wanted it to highlight the day-to-day work of addiction counselors and the powerful decision making done by many young adults during their addiction treatment. And I wanted it to be based on our first two sectors in the Alliance. That writing was published in early 2017 (Crowe, Hennen, & Coon, 2017).

A panel with representatives from each sector was developed for national conferences as suggested during our 2016 summit. I was fortunate to be a member of the touring panel in 2017 that presented the following:

- The Offender, the Defender, and the Student: Drug Court, Professional Monitoring, and Collegiate/Youth Recovery Organizations Working Better Together. Advancing Justice: The National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP) Annual Training Conference.

- Linking CRP’s and Those They Serve to Other Systems of Recovery Advocacy: A Recovery Alliance Panel. The 8th National Collegiate Recovery Conference (The Association of Recovery in Higher Education – ARHE).

- Linking Lawyers Assistance Programs and Those They Serve to Other Systems of Recovery Advocacy: A Recovery Alliance Panel. The American Bar Association Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP) 2017 National Conference.

During these presentations the differing systems described themselves to each other and to the audience. And they discussed opportunities for collaboration and related improvements as part of the presentation. It was very interesting to hear the responses of the panel members and the audience members. It was exciting to hear and see collaborations being formed in real-time by attendees. And it was exciting to hear and see the focus develop across the longer and specific life course of the person served – rather than be limited to the closed timelines of eligibility within programs where panel members or attendees worked. The Recovery Alliance concept was getting some traction.

In spite of that success, we wanted to continue to improve our panel process. We doubled back in 2018 to one of the national conferences and gave our panel process another try.

- Educated, Employed and Impaired: How I Almost Lost It All and the Alliance of Treatment Courts, Professional Monitoring Organizations and Collegiate Recovery Programs That Could Have Helped. The National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP) Annual Training Conference.

This panel event included our most “real” story/sharing. I must say it was very moving and eye-opening for the room of attendees. The message was perhaps our clearest call to action – a call to collaborate across sectors for the sake of the person served.

During those years and since, we have moved from national presentations and working meetings toward various presentations and collaborative/working meetings at the state, multi-county, and county levels. We have noticed that as the focus becomes more local, the traction of our message seems to improve.

In the next post of this series, I’ll describe the expansion and clarification of our model and methods. We ended up including many more sectors. We benefitted from the lessons of our earlier efforts. And we became even more action-oriented by getting various collaborative work groups going to help address needs closer to the local level.