I was first introduced to SMART Recovery by hearing that it was an alternative to AA or NA. Having been through 12-step programs in the past with some success, I wasn’t sure I wanted to walk away from what I already knew. What I have come to learn is that SMART Recovery can be an alternative to 12-step programs, but it also can be an addition to other programs.

I went to the SMART Meeting finder on the website www.smartrecovery.org and found several meetings, both online and in-person, and decided to go to an in-person meeting held at a community center in my neighborhood.

When I entered the meeting room, I was nervous. I didn’t know what to expect. What I found was a welcoming group, eager to help me in my recovery journey. The meeting started with the Facilitator reading the guidelines for the meeting. Then the group began with a “Check-in” when each member had a chance to say what brought them to the meeting or what had happened with them recently. The first thing I noticed is the way everyone introduced themselves. Nobody said they were an alcoholic or an addict. It felt odd after being at meetings where I said my name and that I was an alcoholic. When it came to my turn, I said my name and told them that this was my first SMART Recovery meeting. I was welcomed and had a few people ask me questions. I wasn’t used to that. Crosstalk is a regular occurrence at a SMART meeting. Another thing that was new to me was the variety of people and their addictive behaviors. The group had some that had a problem with alcohol, some with drugs, and others for non-substance issues such as gambling.

After everyone had a chance to speak, the Facilitator presented a tool from the SMART Recovery Handbook. We were told that the tool was based on the first of the 4 points in the program.

- Building and Maintaining Motivation

- Coping with Urges

- Managing Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors

- Living a Balanced Life

The tool presented was doing a cost benefit analysis of our addiction. I had done CBAs before, but never one for something like that! It was enlightening. It became obvious after completing the CBA that I was giving up long-term benefits for short-term relief. I had suspected that was the case but putting it down in black and white was truly an “Ah hah” moment.

Once the CBAs had been completed by the group members, the Facilitator asked what everyone thought of the exercise. The group had a discussion about what they had discovered. What I discovered is that I was not alone. My costs were similar to others in the group. From legal issues and the costs associated with that, to the loss of trust from others close to us, we shared a common bond that made me feel comfortable opening up to the group.

After the group conversation, the Facilitator asked the group to do a “Check-out”. The check-out allowed each member to say what was most meaningful to them in the meeting. This again showed me that I was among other people with whom I had a lot in common. I was not the only one to have that “Ah hah” moment.

Since that first meeting I have become a fan of the tools presented. SMART Recovery has given me the chance to see my addictive behaviors in a different way. From coping with urges using the DEADS tool and giving a persona to my urges using the DISARM Method, to learning how to set healthy boundaries with concepts like Enlightened Self-interest, I have learned to successfully live a life beyond my addictive behaviors.

Having found a program that worked so well for me, I decided to take the SMART Recovery Facilitator’s Training Program to start a meeting in my community. Being a volunteer Facilitator is very rewarding, and now I get to be the Facilitator welcoming people to their first SMART Recovery meeting!

“Going Upstream: Addiction Care for the Masses”

Lecture by Dr. William Miller 5/3/23

Dr. William R. Miller is Emeritus Distinguished Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at the University of New Mexico having served as Director of Clinical Training and as a Founder and Co-Director of the Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions (CASAA). His publications include 65 books and over 400 articles and chapters. Fundamentally interested in the psychology of change, he introduced the method of motivational interviewing in 1983. The Institute for Scientific Information has listed him among the world’s most cited scientists.

Two years ago, I started talking about the likelihood of the pandemic related isolation and turmoil leading to dramatic increases in substance misuse. I termed it an addiction tsunami, others made similar comparisons. The analogy is holding. COVID was the precipitating earthquake. The water is now beginning to rise and envelope a fragile service infrastructure teetering on collapse. It is probable that we are seeing only the initial ripples of this tidal surge.

We have been long vulnerable to the kinds of shocks and traumas we are now experiencing. The COVID-19 pandemic was like an extraordinarily powerful earthquake. Hundreds of thousands have died, and our behavioral health and medical care infrastructure has been severely damaged by the shocks. Our medical care professionals and first responders are particularly vulnerable to substance misuse as they are exposed to long term trauma. We are also ill prepared for this because of deep underlying stigma in these professions. All this before the water started to creep up.

We are woefully ill prepared for what is happening, and what we have focused on has generally been interventions not broadly focused enough to meet the needs of our diverse communities. We have a long-term addiction epidemic decades in the making. Unfortunately, in the last decade it has been narrowly framed as an opioid epidemic. This has had extremely negative and long-term consequences and hobbled our capacity to respond effectively.

We had largely ignored the steady increase in alcohol related deaths (which doubled between 1999 and 2017). A significant facet of the crisis. Instead, we have long focused on overdose deaths. Overdose deaths are a metric that policymakers find appealing because it is easily measurable. It is important to point out that such a narrow focus results in us failing to address the complexity of addiction. We end up ignoring the myriad of ways that addiction kills beyond overdose. We fail to address critical issues such as concomitant benzodiazepine use with opioids which according to NIDA is associated with one in three overdoses. We miss wider solutions by too narrowly conceptualizing the problem.

Consider how street drug use patterns are increasingly complex. As noted above, most persons addicted to opioids are using multiple drugs. This study published in Molecular Psychiatry found that more than 90% of individuals with OUD used more than two other substances within the same year, and over 25% had at least two other substance use disorders along with OUD. Addressing opioid addiction in isolation from other drug use is unhelpful at best, and like the concept of the war on drugs will ultimately be judged as a poor way to frame what actually is occurring. We put on horse blinders and fail to address the full scope of the problem we face, and the water continues to rise.

These complexities include drugs like xylazine, which “gives legs” to a high from any opioid through a synergistic effect. The combination of powerful opioids with this powerful non-opiate sedative is creating a medical and addiction care nightmare. We simply do not have the infrastructure available to effectively address these needs. These patients require intensive medical care provided in close coordination with intensive addiction treatment for extended periods of time. We do not have the capacity in our public service system for these patients. We have been caught flatfooted, dealing with a type of drug use adaptation that was entirely predictable. The water gets deeper.

Some of what we are seeing:

- The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use – Drug overdose deaths have sharply increased – largely due to fentanyl – and after a brief period of decline, suicide deaths are once again on the rise. These negative mental health and substance use outcomes have disproportionately affected communities of color and youth.

Alcohol-related deaths soared 25.5% in 2020. During the two decades prior to the pandemic, alcohol-related deaths increased around 2.2% per year. In 2021 alcohol related deaths saw an increase of 9.9% over 2020. Overall, alcohol played a role in 3 out of 100 (3.1%) deaths in the United States in 2021.

Like a tsunami, the longer we wait to respond, the more devastating the consequences will be and the harder it will become to get people into recovery. Like a tsunami, increases in drug and alcohol use across society will lead to a long-term surge in addiction. It will result in an increase in addiction for those most vulnerable to it as a result of things like genetics and exposure to trauma. Boredom, lack of purpose and loneliness may also be significant contributing issues. These upstream causative factors need to be addressed even as we try and pull people out of the water.

Surging water in a tsunami overruns the low ground and weak spots. Our public care SUD workforce and infrastructure in that low ground that is being inundated. It is particularly vulnerable because the type of long-term investment it requires to remain viable is not where resources have historically been invested. We have had a workforce crisis over the course of my decades in the field and we kept pushing off the solutions. Crisis fails to describe what we now face.

This will play out in time as measured in decades. It comes at a time when our service infrastructure and workforce were already in bad shape. It is highly probable that addiction related deaths over time will eclipse the direct loss of life from the pandemic by several multitudes. We are losing treatment and recovery support centers and care infrastructure at the very moment we need to be fortifying them and preparing for the increases in demand.

While significant amounts of new dollars from the opioid settlements will go to needed pharmaceutical treatments for opioids, people require comprehensive care and support beyond medication only remedies. Money had not flowed to the rest of the care infrastructure in similar ways as it has to MAT. Federal opioid crisis initiatives focused on infusing short term dollars to the states targeted on opioids that did little to address the long-term needs of the care system. These were “spend quickly or lose” dollars, not long-term investment. Money went to where it could be spent fast and far too often not to where it was needed most. In defense of our allocation systems, they are not really designed or resourced to do what we need done, so quick money was better than no money, which was the other door.

Single drug focused interventions and short-term harm reduction efforts that do not lead to comprehensive treatment and recovery will not get us to the safety of high ground. If we were serious as a nation in addressing SUDs, we would need to conceptualize addiction needs in America much like we do cancer, with a myriad of interventions, services and supports over the long term that can be individualized to the needs of the individuals, families and communities served. Long term remission is the standard of care for cancer. We do not think in those terms about addition. We should.

This would need to include:

- Building an SUD service infrastructure that is on the scale of the need for these services in America. The one we have typically does not even provide people with the minimum dose of effective care for patients with average needs.

- Developing a sustainable and properly resourced SUD service system workforce.

- Establishing a recovery-oriented system of care that meets the long-term needs of the diverse communities served. This would require the authentic representation of communities of recovery in the design, implementation, facilitation, and evaluation of programming at all strata, from federal, state, regional to the local community levels.

Recently, the Governor of California deployed the National Guard in the tenderloin district of San Francisco to address open air drug dealing. It is driving away business and making living in the city untenable. Those who can afford to leave it are heading for the hills. This is one major city in one major state, yet these dynamics are playing out across America. The truth is that “those people” are quite often “our people.” Our neighbors, our friends, our family members. We are not even close to taking this emerging crisis as seriously as we should. Considering just opioids and not the impact of other illegal drugs or alcohol, in 2022, the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee (JEC) found that the opioid epidemic cost the United States nearly $1.5 trillion in 2020, or 7 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), an increase of about one-third since the cost was last measured in 2017.

This is our leading domestic challenge in the United States, and conditions are worsening. What would we do if this was any other issue beyond the highly stigmatized condition that it is? When will we start doing those things?

The water is rising around us while we consider these questions.

By Stefan Neff, SMART Facilitator.

My therapist shared a great tool with me called an Urge Jar which is a simple yet effective technique that can help you break bad habits or form new ones. It works by creating a physical or virtual jar to hold your urges or cravings at bay. This technique has gotten me out of many sticky jams in the past.

The idea behind Urge Jar is that instead of giving in to your urge or craving, you acknowledge it and pull an activity from the jar even if you don’t feel like it. This allows you to take a moment to reflect on your actions and the reasons behind them. It also helps you to build self-control and discipline.

To create your Urge Jar, follow these steps:

1. Choose a container: You can use any container you like, such as a jar, a box, or a pouch. You can also create a virtual jar by using an app or a note-taking tool.

2. Label the container: Write “Urge Jar” or something similar on the container to remind yourself of its purpose.

3. Identify your triggers: Think about the situations or emotions that trigger your urges or cravings. This could be stress, anxiety, boredom, or social pressure.

4. Decide on a strategy: Determine how you will use the Urge Jar. For example, you could write down 30-50 activities and add them to your jar for every time you have an urge, and place it in the jar. Activity examples: clean the dishes, do your laundry, go for a walk or walk the dog, yes even clean the toilet, wash the windows, whatever you can do to distract yourself from your Urges and Cravings.

5. Use the jar: Whenever you feel an urge or craving, take a moment to acknowledge it and then pull at random one of your activities from the jar. You can also use the jar to track your progress and celebrate your successes.

Your Urge Jar can be used for a variety of habits, such as drinking, smoking, drugging, overeating, or procrastinating. It can also be used to form new habits, such as exercise or mindful meditation.

The key to the success of your Urge Jar is consistency. You need to use the jar every time you feel an urge or craving, even if you give in to it. Over time, you will build the self-control and discipline needed to break your bad habits and form healthy new ones.

In conclusion, your Urge Jar is a simple and effective technique that can help you break bad habits and form new ones. By acknowledging your urges and cravings and replacing them with a new activity from the jar, you can build self-control and discipline. Try it out for yourself and see how it can help you achieve your desired recovery goals.

Now it’s time to make your list of activities to fill your Urge Jar to the rim.

JAMA published new research on buprenorphine initiation and retention and the findings are disappointing.

The study looked at a database of retail pharmacy records from 2016 to 2022 that includes 92% of all retail pharmacies. (93, 713, 163 prescriptions)

If I understand correctly, this excludes buprenorphine dispensed in emergency settings. Those patients would only be included if they followed up and filled a prescription at a pharmacy. Medication dispensed in emergency settings is usually limited to a few days and would presumably have the lowest retention rates. The exclusion of those emergency prescriptions should tell us only about people who took the steps of going to a pharmacy and filling a prescription.

Initiating buprenorphine was defined as a prescription for a patient without a filled buprenorphine prescription in the last 180 days.

Retention was defined as continuous buprenorphine prescriptions filled over 180 days without any gaps of more than 7 days.

What did they find? [emphasis mine]

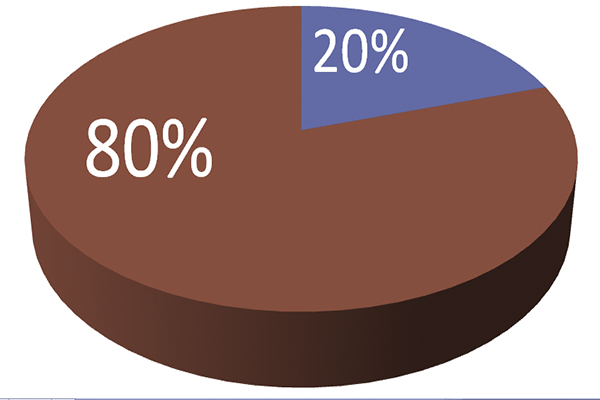

During January 2016 through October 2022, the monthly buprenorphine initiation rate increased, then flattened. This flattening occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting that factors other than the pandemic were involved. Throughout the study period, including in 2021-2022, only 1 in 5 patients who initiated buprenorphine were retained in therapy for at least 180 days, a rate similar to that found in a prior study examining data through the end of 2020.4,5

Chua K, Nguyen TD, Zhang J, Conti RM, Lagisetty P, Bohnert AS. Trends in Buprenorphine Initiation and Retention in the United States, 2016-2022. JAMA. 2023;329(16):1402–1404. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.1207

The stalled initiation rates are disappointing in the context of massive federal, state, and local efforts to increase buprenorphine treatment.

How do the authors explain these findings? [emphasis mine]

These findings suggest that recent clinical and policy efforts to increase buprenorphine use have been insufficient to meet the need for this medication. A comprehensive approach is needed to eliminate barriers to buprenorphine initiation and retention, such as stigma and uneven access to prescribers.

Chua K, Nguyen TD, Zhang J, Conti RM, Lagisetty P, Bohnert AS. Trends in Buprenorphine Initiation and Retention in the United States, 2016-2022. JAMA. 2023;329(16):1402–1404. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.1207

Other Explanations

I don’t doubt that stigma and barriers to access to prescribers play a role in these findings, but I imagine there are more important factors at play. After all, these were patients who received, accepted, and filled a prescription–they found a prescriber and stigma didn’t prevent them from starting treatment.

Is it possible the treatment isn’t delivering the outcomes these patients need or want? (It’s important to note that this could mean a lot of things. Some related to the medication, some not.)

For example, we know that polysubstance problems are the norm among people seeing treatment for opioid problems. If a patient presents with opioid use disorder, alcohol use disorder, stimulant use disorder, and cannabis use disorder, do they have 4 disorders? Or, do they have one disorder–addiction? If they have addiction, and we only treat opioid use, how successful is that likely to be? For someone with addiction, is “opioid recovery” an appropriate clinical endpoint?

For those patients with addiction, it is a uniquely complex bio-psycho-social-spiritual illness. Does the treatment these patients were provided address these complex and intersecting needs? Or, did it just target one of the biological factors?

Further along these lines, these findings may point to tensions in poorly developed and poorly aligned clinical, community, and individual models for recovery and wellness. Bill White explored this in a 2012 speech:

…historically the mental health field has had a very well-defined definition of partial recovery but literally no definition, until very recently, a full recovery from severe mental illness. We now have long-term studies of the course and trajectory of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, for example, that are really challenging that, and really beginning to signal the emergence of the concept of full recovery from some of the most severe complex psychiatric disorders.

On the addiction side, in contrast, we’ve had a very well-defined—a reified, if you will—concept of full recovery and no concept of partial recovery. In fact, it’s almost heresy to even begin to talk about a legitimized concept of partial recovery within the addictions field.

There’s a third concept within this framework that Ernie Kurtz and I ran into. We began to find scientific evidence in lots of anecdotal reports from therapists about people who got better than well. What I mean by better than well is that these are not people that we simply extracted the pathology out of their lives, but these are people who, not only went on to recover, but they went on to live incredibly rich lives, in terms of the quality of their life and service to their communities, and these are people who would later begin to talk about addiction and recovery was for them a blessing.

Experiencing Recovery, 2012 Norman E. Zinberg Memorial Lecture, William L. White

This “better than well” concept fits nicely with emerging models of post-traumatic growth.

In the context of the overdose crisis, more than ever, we need legitimized models and pathways for each to reduce harm, improve QoL, and achieve stable recovery for the greatest number of people. And, we need to avoid pitting them against each other.

Acknowledged or not, we have systems, resources, communities, and providers based on particular models. It might help to acknowledge this and address it much more explicitly. I imagine we’ll be stuck as long as we continue to have providers and systems that delegitimize and disavow responsibility for these pathways. This doesn’t mean providers need to be all things to all people, but validation and coordination would go a long way.

This article originally appeared in the American Psychological Association’s Society for Psychopharmacology and Substance Use Division 28 Newsletter

A few years ago, I visited a methadone clinic in Baltimore and sat with several of the patients discussing the challenges they faced sticking with their treatment for opioid addiction. Every one of the individuals around the table told me the same thing: The biggest challenge was not having a place to sleep. Without housing, so much of their time was consumed arriving early enough to a shelter so that they could get a room, or other logistical challenges related to their basic life necessities—obtaining meals was another challenge—that they frequently could not make it to the methadone clinic on a given day.

Talking to these patients demonstrated to me that treatment isn’t just about the delivery of a medication or some other intervention that works in ideal laboratory conditions. It is also about the social and economic factors that shape people’s real lives, day to day. Across many institutes of the NIH, research is increasingly focusing on social determinants of health: factors like work and housing instability, food insecurity, racism, class discrimination, immigration status, and stigma and their integral role in shaping risks and treatment outcomes for many health conditions. Understanding and finding ways to intervene in such factors are now also central priorities for my institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The NIDA and NIAAA -led nationwide longitudinal Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study is already yielding striking new science on some of the neurodevelopmental mechanisms by which various forms of social adversity influence many aspects of mental health. Mitigating the adverse effects of environmental risk factors like social-economic disadvantage has long been a target of NIDA-funded substance use prevention research, and with projects like the HEALing Communities study, we are now bringing a similar mindset to addiction care and recovery. For instance, data is being gathered on how providing transportation to patients receiving medication for opioid use disorder increases retention in treatment.

Measuring social determinants of health can help researchers better design treatment interventions and services, as well as make addiction care more equitable. Research in other areas of medicine has already revealed the distorting effects of failure to take that step. For instance, a 2019 reanalysis of the data from a huge international clinical trial of hypertension medications found significant disparities in blood-pressure control, all-cause mortality, and various heart-related outcomes depending on whether participants had received their care in low-income versus high-income neighborhoods—differences not accounted for by the medications participants received or by their clinical characteristics, and ignored in the original analysis.

In clinical trials of new medications to treat addiction, it is crucial that we take into account social determinants that influence participants’ access to quality healthcare. Besides enhancing clinical science, measuring such factors could also help personalize our approach to addiction treatment, for instance by helping determine which patients in opioid addiction treatment might benefit from counseling or other services in addition to medications.

No aspect of health exists in a bubble, and this is especially true of substance use and addiction. Researchers keep in mind the diversity of people affected and how their different social contexts and circumstances affect their prospects, especially when those factors can be modified to make treatment more successful and recovery more likely.

One of the major accomplishments of the earliest stages of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement was the founding of Faces & Voices of Recovery in 2001. Pat Taylor was its first Campaign Coordinator, heading the organization from 2003-2014. One of my early memories of her is watching her facilitate meetings of the Association of Recovery Community Organizations at Faces & Voices of Recovery (ARCO) where much of the early national recovery community gathered and worked to move forward, together.

For me, the most significant of these ARCO Executive Directors Leadership Academy meetings was on November 15, 2013, in Dallas, Texas. Bill White addressed the gathering with his thoughts on “The State of the Recovery Advocacy Movement.” It was an important time for me as I was learning about RCOs, and the work being done to strengthen recovery efforts across America. Pat was there, helping to hold the whole thing together in her own way.

One fact I want to highlight. Pat is not in recovery from an addiction. To the best I can determine, this did not matter in the least to any of us involved with Faces & Voices of Recovery. It certainly did not matter to me; it was something I soon forgot as I saw her in action embracing and supporting the needs of the fledgling national recovery community organization she led. She has lived most of her life working alongside us and her servant leadership style came through in everything she did. I have known a few other such recovery allies who take the time and energy to understand us and to listen and support our goals in ways that it matters little if their lived experience differs from ours. Her leadership personified that we embrace authentic allies who work with us in ways that resonate the “nothing about us without us” rallying cry that started at the very beginning of the new recovery advocacy movement and echoes through our current era.

Pat has over 50 years of experience developing and managing local and national public interest advocacy campaigns on a range of issues including healthcare, community development and philanthropy. While at Faces & Voices, she led the organization’s development into the national voice of the organized addiction recovery community, building a membership of over 40,000 individuals and organizations, creating ARCO and launching the Council on Accreditation of Peer Recovery Support Services. Today, Pat serves on the board of The Recovery Advocacy Project. She is a graduate of the University of Michigan and the author of numerous publications and recipient of numerous awards for her work.

- What brought about the formation of Faces & Voices of Recovery? How did you get connected to it? Is there a special memory you have about those early days?

Faces & Voices grew out of the efforts of many individuals and organizations focused on mobilizing and organizing the recovery community. Many were part of the National Forum, which met regularly in Washington, DC to advance addiction prevention, treatment, and recovery policies. Participants included Johnny Allem, Johnson Institute; Paul Samuels, Legal Action Center; Paul Wood, National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence; Sis Wenger, National Association for Children of Alcoholics; Bill Butinski, National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors; Claire Ricewasser, Al-Anon; William Cope Moyers, Hazelden Foundation; and many others. Jeff Blodgett organized the St. Paul Summit for the Alliance Project, bringing together local recovery advocacy groups, already strong and active at the local level, to develop a more organized constituency that would prioritize addiction recovery at the local, state and national levels.

Before coming to Faces & Voices, I ran the Alcohol Polices Project at the Center for Science in the Public Interest and worked at Ensuring Solutions to Alcohol Problems at George Washington University. It was people in recovery who showed up to testify for legislation to require warning labels on alcoholic beverage containers and to advocate for raising alcohol excise taxes. Through this work, I knew some of the people who organized the Summit and helped launch Faces & Voices. So, when I heard about the job opening for a Campaign Coordinator, I was familiar with some of the advocates. I was intrigued and excited by the opportunity after learning more about the campaign.

Faces & Voices took off after the Summit and did not become its own 501 (c)3 until 2004. As it was getting off the ground, Susan Rook, who was in recovery and had worked for CNN and Rick Sampson, who had been at SAMHSA, were its leaders. One of their early efforts included calling attention to the Christian Dior advertisement campaign for their product Dior Addict to highlight how the medium was being used to sensationalize, stigmatize and sell their perfume. Those early efforts led to some major stores pulling the product from the shelves, an early victory.

You asked me about my memories from the early days. One is learning about the importance of taking time and spending resources to understand the priorities of the recovery community. When I called to introduce myself to Faces & Voices board members, many brought up the Million Man March that had happened a few years earlier in Washington, DC. They wanted to organize a similar event to put a face and a voice on recovery, and stand up for recovery with family members, friends, and allies in the nation’s capitol.

As an organizer I was excited and kept this in mind as Faces & Voices developed programming. There hadn’t been many public recovery events since Operation Understanding in 1976. Faces & Voices worked with HBO on the release of its Addiction program, with A&E on its New York recovery rallies and helped organize Recovery Month marches and rallies that included voter registration, participation by elected officials, recovery entertainment and activities, fueling the building of a movement that operated in the public space.

When Bill White wrote that the central message of this new movement was that permanent recovery from alcohol and other drug-related problems is not only possible but a reality in the lives of hundreds of thousands of individuals and families, it was a dramatic turning point and spot on. He articulated what many people had been thinking individually — that the views and needs of people in recovery, family members, friends and allies could not be ignored if we wanted to make it possible for more people to recover from addiction to alcohol and other drugs. To shift from “treatment works,” and “addiction is a disease,” this new collective movement would need to work to make policies and practices recovery-focused and recovery-oriented. At the time, we didn’t even know how many people were in recovery in the U.S.!

Bill White has played a number of important roles in the New Recovery Advocacy Movement. One that probably no one anticipated is that his efforts to document recovery history through his work including Slaying the Dragon was and remains vital to the development of the movement. In all of his writings, presentations and consultations, he has helped us understand that people in recovery, family members, friends and allies have unique knowledge and skill sets that must be front and center if we are going to make it possible for even more people to find and sustain recovery.

His work contributed to the development of Faces & Voices’ mission to mobilize the addiction recovery community to seek and implement public policies that support recovery from addiction to alcohol and other drugs; break down barriers that preclude access to recovery; change public attitudes to prioritize addiction recovery and show the public and policymakers that recovery is a reality for over 23 million Americans and their families in communities across the country.

One thing we got right was working hard to make sure that the voice of the recovery community was front and center in all of our work. Early on, we wanted to develop recovery messaging, so that the public could understand the reality of recovery and so that advocates had language to talk about their recovery. We tested different messages using focus groups of people in recovery. They rejected words like “survivor” or “champion” used by other movements and embraced person-centered language. We started using the term “person in long-term recovery” after listening to people with lived experience.

Another is that at the Summit and throughout its history, Faces & Voices worked hard to embrace all pathways to recovery, including people using various pathways in its leadership as well as family members. We also learned to appreciate the power of the bipartisan nature of our work and the power of story. In St. Paul, Senator Paul Wellstone (D) and Representative Jim Ramstad (R) spoke out, transcending the partisan divide. Just as Republicans and Democrats alike are affected by addiction, recovery leaders emerged from both sides of the aisle. That started at the Summit and continued with the formation of the bipartisan Addiction and Recovery Caucus, passage of the Wellstone Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, among other efforts.

One thing that was missed, and there were others, was understanding and promoting harm reduction policies and practices.

- What was the relationship between Faces & Voices at the national level and recovery community groups across the country? Our history illuminates that inherent tensions can occur. This was true in the era of Marty Mann and the NCA and other eras in recovery movement history as well. Reflecting back, what helped pull groups together in the time you were involved with Faces & Voices?

We had a very close relationship, highlighting the work of those organizations and including recovery communities in all levels of decision making, formally and informally. We worked to develop programming and activities that would strengthen their ability to carry out their missions on the ground back home in their communities.

We also worked hard to have a board that represented the diversity of the recovery community – including recovery pathways, regions, race, gender, and recovery status. One important effort was to have At-large and regional representatives on our Board to ensure connection to local communities. Local groups could interact with regional Board representatives, who could bring local concerns to the national organization.

In those early years we worked to grow Recovery Month participation by local groups, as members of the Recovery Month Planning Partners at SAMHSA and through Faces & Voices networks. We developed programming like Rally for Recovery! National Hub Events that occurred in different communities across the country year to year. People organized runs, marches, marathons, rallies, concerts, and speaker events. And we made sure to use these opportunities where the recovery community gathered, to register voters and engage elected officials.

Over the years, we developed opportunities for individuals and organizations to be part of the movement. We developed Recovery Community Organization Toolkits that local grassroots communities could use to develop their own RCOs to strengthen recovery capital in their own communities. Groups could then get involved in the Association of Recovery Community Organizations (ARCO). We organized leadership academies that brought leaders from RCOs together from across the nation so they could share their experiences, learn together and help inform us on how to support their needs. We worked hard to use our national presence to strengthen the RCOs across the nation. Working with RCOs we developed CAPRSS to set accreditation standards for RCOs.

There was a tremendous void in recovery research. Working with Alexandre Laudet, we put out the very first national survey The Life In Recovery Survey to quantify and measure the effects of recovery over time. People across the country took the survey and it’s been widely shared, illuminating the power of recovery to transform lives and communities.

The talented and dedicated people who served as Board members and those who worked at Faces &Voices were critical to its growth and development. They were amazing and many went on to serve in key positions, influencing public policy and perceptions of recovery. People including Carol McDaid, Dona Dmitrovic, Tom Hill and Tom Coderre, helped build Faces & Voices from the ground up.

It was important. When Bill White made that presentation, we were in a period of transition in the recovery movement. Faces & Voices was over ten years old! Peer support was beginning to look more professional, and issues around the risks and benefits of professionalization of lived experience workers were surfacing as well as the role of advocacy in the movement. He raised the importance of keeping eyes on community building recovery capital and anti-discrimination efforts that were necessary to more fully realize opportunities for long-term recovery.

Here’s one example of the changes in the movement. The Association of Persons Affected by Addiction hosted the Leadership Academy at their recently opened Recovery Community Center. They were just getting off of the ground twelve years before. They had reached the level of operation that they were undergoing CAPRSS certification in 2013.

Recovery-oriented services were expanding rapidly across the country and recovery was coming out of the closet for many Americans. New organizations like Shatterproof were being formed and the Anonymous People, which at its core is the story of Faces & Voices of Recovery, had been recently released and was being aired across the country. There were so many new voices, interests, and ideas to think about. The movement was growing with all of the opportunities and challenges that came with it.

When I reflect back on that moment now, what we were working on was recovery representation across our whole system of care and support. We knew it had to be about more than peer services incorporated into the treatment system.

What do you see as the greatest accomplishment during the era you were at the helm of Faces & Voices of Recovery?

There was not just one thing. We were working on a number of fronts to advance recovery. We put together ARCO and the Leadership Academy to focus on and support recovery community organizations. We developed CAPRSS to support standards for peer recovery support services and keep the recovery community in the driver’s seat. We developed and released the Recovery Bill of Rights, a statement of the principle that all Americans have a right to recover. In many ways, that statement reflects what Faces & Voices accomplished, the recovery community coming together as an organized community and constituency, building its own agenda, and acting collectively to implement it with support from allied organizations.

- What insights do you have now looking back at the recovery movement and what it has accomplished?

I look back and realize that a lot has been accomplished. If you think back to what was happening at the first Recovery Summit in 2001 and what’s going on today, it’s truly inspiring. Hundreds of recovery community organizations and recovery-oriented policies developed out of our efforts. Hundreds of thousands of people have participated in public events celebrating recovery, with many of them registering to vote and participate in local, state and national elections. There were successful efforts to expand legal protections for care through the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) made possible because of the advocacy of the organized recovery community. We showed America that there is hope, that recovery is a reality and that recovery voices matter.

Even as I say this today, addiction is exacting a devastating toll on families and our communities. So much more needs to be done. To continue moving forward, we are going to have to work even harder to be inclusive of all the diverse recovery and other allied groups that have formed. There is going to need to be a concerted effort to figure out how to bring all of these groups together and work on issues of common concern.

What are you doing now?

One of my passions is gardening, so I’ve had a chance to build my small landscaping business. My daughter and her family moved from Austin, TX into our house in Maryland, so my husband Bill and I are now renters. We’ve been traveling a lot and during the pandemic, we were zoom school proctors for our grandson, quite the experience. I also still have my hand in recovery efforts and serve on the Board of Directors for the Recovery Advocacy Project, I’m really excited about the work they are doing.

- What would you tell future recovery community leaders to pay attention to in respect to risks and opportunities?

I’d suggest one way to move forward is to organize to address the way that discriminatory policies create barriers for so many people to get their lives back on track. We should actively work to eliminate discriminatory policies where they exist in healthcare, employment, housing, and quality of life issues. If these policies are ignored – or in some cases, strengthened, it will be a missed opportunity for building recovery-oriented communities.

I’d encourage them to pay close attention to what can happen if there is an overemphasis on peer services in their organization and community. It’s very important to keep a focus on advocacy and building strong communities of recovery.

There’s an untapped opportunity that has been well used by other social movements – running candidates for public office. A few people have already run and won as persons open about their recovery in the U.S. As a matter of fact, they used their recovery status to recruit supporters and build support for their campaigns.

And last, we need to build a dynamic movement that is creative and inspires others to join in.

- Is there a question I did not ask you would like to answer?

I think it’s important to highlight how and why it’s important for people to join us and get involved. While some people who were in the formative stage of the movement ended up with government appointments, there are so many opportunities to organize and act locally and engage a new generation of recovery advocates.

.

After screening for harmful alcohol use, researchers in a 2022 study1 examined differences based on age – with some interesting results.

The study examined…

…data from 17,399 respondents who reported any alcohol consumption in the last year and were aged 18 and over from the 2016 National Drug Strategy Household Survey…”

The authors said the aim of their study…

…was to measure age-based differences in quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and how this relates to the prediction of harmful or dependent drinking.”

The bottom-line finding was that:

- quantity mattered more for the older population, and

- frequency mattered more for the younger population.

The authors stated…

In older drinkers, quantity per occasion was a stronger predictor of dependence than frequency per occasion. In younger drinkers the reverse was true, with frequency a stronger predictor than quantity.”

Interestingly, based on their results, the authors wonder if…

- heavy episodic drinking among younger people is the kind of drinking from which most can “age out”, without intervention;

- the factor of consistent drinking among young people can eventually be developed and refined as a screening marker to help prevent serious clinical progression;

- and if screening problematic drinking among older adults should center on drinks per occasion.

The authors close by stating…

…it appears that clinicians…might wish to look out for young drinkers who are drinking like older people (frequently) and older drinkers who are drinking like young people (more per occasion).”

They note that common tools currently used to screen for alcohol problems do not function in this manner.

A simplified yet thorough overview and discussion of this research is available.

Reference

1Callinan, S., Livingston, M., Dietze, P., Gmel, G., & Room, R. (2022). Age-based differences in quantity and frequency of consumption when screening for harmful alcohol use. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 117(9), 2431–2437. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15904

Very recent original research has found initial evidence that the paternal use of alcohol prior to conception produces physical defects and abnormalities that resemble those caused by maternal drinking during pregnancy.1

What kinds of abnormalities were found to be associated with paternal drinking prior to conception? The study found alcohol-related fetal abnormalities of the brain and face.

But the researchers also found another impact. They found paternal alcohol use before conception also increases the impact of maternal drinking on development of the fetus.

Interestingly, rather than merely examining drinking as an all-or-nothing variable, the investigators found that the effects of pre-conception paternal drinking were correlated with alcohol dose.

A simplified overview and discussion2 of this research is available.

The authors discuss the relative lack of research in this area, stating that,

…due to the misconception that sperm do not transmit information beyond the genetic code, the influence of paternal drinking on the development of alcohol-related birth defects has not been rigorously examined.

One might wonder if this area of research holds relevance for public health promotion The researchers state that,

In 1981, the U.S. Surgeon General issued a public health advisory warning that alcohol use by women during pregnancy could cause birth defects.

and,

…our studies are the first to demonstrate that male drinking is a plausible yet completely unexamined factor in the development of alcohol related craniofacial abnormalities and growth deficiencies.

They go on to state that…

Our study demonstrates the critical need to target both parents in prepregnancy alcohol messaging and to expand epidemiological studies to measure the contributions of paternal alcohol use on children’s health.

References

1Thomas, K. N., Srikanth, N., Bhadsavle, S. S., Thomas, K. R., Zimmel, K. N., Basel, A., Roach, A. N., Mehta, N. A., Bedi, Y. S., & Golding, M. C. (2023). Preconception paternal ethanol exposures induce alcohol-related craniofacial growth deficiencies in fetal offspring. The Journal of clinical investigation, e167624. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI167624

2Knight, R. Father’s Alcohol Consumption Before Conception Linked To Brain and Facial Defects In Offspring. Texas A&M Today. April 12, 2023.

“Safe supply” is a promotional term, when what is needed is careful evaluation of the risk of such initiatives to increase addiction, toxicity, and overdose.

Roberts, E., Humpreys, K. (2023) “Safe Supply” initiatives: Are they a recipe for harm through reduced healthcare input and supply induced toxicity and overdose? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.23-00054

I’ve recently published a couple of posts on drug policy (here and here), trying to shine a light on how broad and complex the topic can be.

This is good news and bad news.

The bad news is that “simple” solutions are never as simple as they sound and that the devil will be in the details. Simple concepts get very complicated very

The good news is that we have a lot more levers than we typically associate with drug policy and that some of them ought to be fairly easy to implement — for example, things like marketing restrictions and zoning of outlets. These policy decisions typically won’t solve “the drug problem”, but they have the potential to influence it.

One of the questions raised was, if we legalize and regulate drugs and one of the goals of that decision is to improve the safety of the drug supply, how do we manage and prevent innovation in the drug supply?

The NY Times has a story on the xylazine’s veterinary use and the search for policy responses to its emergence in the drug supply.

Stories about the emergence of fentanyl and xylazine often frame them as examples of poisoning of the drug supply. However, their emergence could just as easily and maybe more accurately be framed as innovations that serve a purpose — to ensure higher potency, lower price, and extend the duration of the effects of the drug.

We demonstrated that preference for fentanyl was increasing between 2017 and 2018 among our cohorts of PWUD who used opioids. In a multivariable analysis, younger age and daily crystal methamphetamine injection remained independently associated with preference for fentanyl. Most commonly reported reasons for preferring fentanyl included more euphoria, longer effects, and development of high opioid tolerance.

Ickowicz, S., Kerr, T., Grant, C., Milloy, M. J., Wood, E., & Hayashi, K. (2022). Increasing preference for fentanyl among a cohort of people who use opioids in Vancouver, Canada, 2017-2018. Substance abuse, 43(1), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2021.1946892

Calls for “safe supply” often frame it as a simple process of ending prohibition (legalizing), getting law enforcement out of the picture, and regulating supply. However, what does that regulation look like? Does it allow innovations like fentanyl and xylazine? How are those regulations enforced and by who?

These calls also often elide the reality of the enormous public and private burdens associated with our regulated supplies of alcohol and tobacco.

All of this brings me back to the belief that we are very poorly served (harmed, actually) by sloganeering in drug policy discussions, whether those slogans are designed to promote a “war on drugs” or a “safe supply.” (It’s worth noting that harm reduction advocates used to avoid “safe” and preferred “safer” as an acknowledgment that PWUD who engage in harm reduction practices continue to face significant risks associated with their drug use.)

Mark Kleiman challenged us to confront drug problems and drug policy by facing the limitations of policy “solutions”, acknowledging the difficult decisions, and not being paralyzed by those limits and difficult choices.

Any set of policies will therefore leave us with some level of substance abuse—with attendant costs to the abusers themselves, their families, their neighbors, their co-workers and the public—and some level of damage from illicit markets and law enforcement efforts. Thus the “drug problem” cannot be abolished either by “winning the war on drugs” or by “ending prohibition.” In practice the choice among policies is a choice of which set of problems we want to have.

But the absence of a silver bullet to slay the drug werewolf does not mean we are helpless. Though perfection is beyond reach, improvement is not. Policies that pursued sensible ends with cost-effective means could vastly shrink the extent of drug abuse, the damage of that abuse, and the fiscal and human costs of enforcement efforts. More prudent policies would leave us with much less drug abuse, much less crime, and many fewer people in prison than we have today.

Dopey, Boozy, Smoky—and Stupid by Mark Kleiman