Forward – Robin Horston Spencer, MHS, MS, MBA, OWDS, RCAT is in long term recovery since 1991. She has done so very much for her community. She is well known for her collaborative efforts with churches, agencies, 12 Step communities and even ballroom dancing! Presently, she sits on several advisory boards locally, statewide, and nationally. She is the proud mother of a son, Leigh James, daughter-in-law, Malika, and two beautiful granddaughters, Jazmin and Jordan Horston, all of Columbus, Ohio.

With over twenty years in human services, Ms. Horston Spencer worked for 16 years exclusively in SUD recovery support services. She received her master’s degree of Science in Human Service (MHS) from Lincoln University, the United States’ first degree-granting historically black college and university (HBCU) where she was inducted into the Pi Gamma Mu, International Honor Society in Social Science and was awarded the Rose B. Pinky Award for Outstanding Contribution in the Human Service Field. While attending Lincoln University she wrote “Training Recovering Individuals with Criminal Histories to Become Advocates and Mentors.” Ms. Horston Spencer was one of the first in Pennsylvania to become a Certified Offenders Workforce Development Specialist (OWDS) and is a certified Recovery Coach Trainer (RCAT). In addition, she has a MBA and MS both from Carlow University. Ms. Horston Spencer helped form one of the first recovery community organization in Pennsylvania. She served as Executive Director of Message Carriers of Pennsylvania until it turned the lights out in July 2021.

I have known Robin for over twenty years. I recall first seeing her at meetings twenty years ago that the state supported to design a recovery-oriented system of care. Robin has long been a passionate and vocal recovery advocate in Pennsylvania. She loves our system so much; she says what is on her mind and the truths of her experiences. Year in and year out, over the years I watched her get marginalized by our system. Her name would come off of workgroups, her organization left in the margins. The things she had to say made some people uncomfortable. She asked difficult questions. She got excluded and sidelined for being candid. Her funding evaporated. It happens to others, and it leads to a system in which people learn only praise is acceptable. Such systems become profoundly impaired. We can’t heal our people until we address these issues, even as raising them makes a person unpopular. We cannot fix the things we hide in the dark.

We should never have lost the first African American run Recovery Community Organization in Pennsylvania. How did this occur in a time when funding and support for other things in our field are so bountiful? By removing the voices of persons and organizations who express constructive criticism, we only guarantee that nothing will change. It will take real courage and self-examination for leaders to fix this. The first step in changing something is acknowledging it, the second step is genuinely supporting its healing. There is a lot to be done if we are to heal these wounds.

During our interview, Robin shared with me a story of how in the early 1960’s, she had a brother who was killed by a drunk driver. The insurance company compensated her family for the loss of this young boy’s life with a $12 check. $12 for the loss of a human being across an entire life span. I have no idea what that kind of pain feels like. I listened and shared with her that I had learned about this kind of anger and hurt by often being the only white person in a room of African American men coming out of our jails and prisons. They did what I had done to get drugs but served sentences for crimes I never even got charged with. They were treated differently because of the color of their skin. Not something I have ever faced. As Robin noted in our conversation, “I wake up black every day, I don’t get a break from this.” This is of course, was not my life experience, but I can listen and support her voice. I can interview her. I can have the courage to also tell the truth about a system I am dedicated to helping fix. We hope our systems have the courage to listen with an open heart nd to work with us collaboratively to fix it.

I cannot fully understand what Robin feels like having experienced being discounted and excluded, but I have had the experience of being removed from the table. As a person in recovery with hundreds of thousands of hours of professional and decades of lived experience, I have found myself openly discounted or ignored when the things I had to say made people uncomfortable and promised opportunities that shift like a pea under those cups as those cups are moved around on the table. It can be debilitatingly painful. It makes me very angry. It also helps me understand to a small extent what Robin and members of our African American recovery community experience in a myriad of ways that I have never had to face. These voices must be heard. It is the first, but not the final step in healing.

- Tell us about yourself, your recovery, and your work to support recovery over your lifetime?

In 1989, my journey into recovery started for me by a “nudge from a judge.” I got caught transporting drugs across state lines between New York and New Jersey. I spent four nights and five days in a jail in Hackensack NJ. I had never been in prison before, it felt like a lifetime sentence. I had no prior conviction record. My father was there to support me. I really had no idea what was going on or even the chance I was being afforded by this judge. He handed me the brass ring of a pretrial intervention and he sent me to an outpatient in Pittsburgh near where I lived. I had no idea what an outpatient was. I didn’t figure out what a gift I was handed by that judge until a very long time later.

Readers who do not have lived experience with addiction and recovery may not entirely understand, but I was focused on doing what I was doing. Addiction works like that. I did not want any part of recovery. As we often do, I just rolled with what I was asked to do and started figuring out how to get around the obstacles to using, which was my focus. I had to come in for urine testing and ended up handing in samples that would show negative. I attended the services they offered and the recovery fellowship they sent me to, but I wanted no part of those people. I just sat in the back. Eventually, a counselor did an observed UT and I got caught. I then stopped using cocaine and shifted to drinking, as we often do.

This went on for about two years. I did not see myself as “one of those people.” I was not that bad. I had a car. I had a house. I had a job. My family loved me. I would listen to what people said and pick out the differences and not what we had in common. I was just doing what I need to do to stay out of jail. For a long time, it seemed to work.

Then one day, on June 10th, 1991, I was sitting in a 12-step fellowship meeting, and someone said that alcohol was a drug. It had probably been said a few hundred times before that, but in that moment, I heard it. I had a sponsor (in name only). I made the move and called this woman up and asked if she remembered me. Of course, she did. I talked to her about my drinking and my drug history. I had a bottle of E & J brandy in the house, and she suggested I pour it out. Pouring out a full bottle of booze was not in my head at all. She offered to stay on the phone as I did it. I poured that E & J down the sink drain on that day. We talked for hours. This stranger showed me love. She was so happy! I had always been so guarded. She got through my armor. She was an amazing person. She helped me save my life.

I stated to hope a little. I kept going to these meetings and to that outpatient and listening more. I moved my chair further up towards the front of the room. I had not really figured out that I was in treatment. I just liked hanging out with these people and the activities that were offered, like card playing, dances, and picnics. I started to have fun and let my guard down a little more.

Right around this time, I met another woman in recovery. She invited me out to Wexford to hang out and see a movie. It was like an hour away by bus. I still did not fully trust, and I wondered if she was going to kidnap me or something. Her and her recovering friends took me to a movie and bought me popcorn. They would not let me pay for anything. I had the best time ever!

Things started to click. Two years later, I completed that pretrial intervention. A lot of difficult things happened in those next few years, but I stayed on track. My relationship, which had gravitated around using, ended. I lost a few of my family members who stood next to me through my using days. Many of the people who helped me so much in that era are gone now. Six years ago, I lost that sponsor who stayed on the phone as the booze went down that drain. So many people had loved me into recovery. I am so grateful for all they did for me. I have tried hard to pay that debt forward.

- You had an instrumental role in forming and running Message Carriers of Western PA. Looking back what would you want people to know about what brought Message Carriers together?

Keith Giles and Reverend David Else had been involved with Message Carriers before I got there. It was essentially a volunteer organization closely associated with the Center for Spirituality in 12-step Recovery. I ended up getting invited to Virginia as the work with the Recovery Community Support Program (RCSP) grant was getting in gear. Dona Dmitrovic, Denise Holden, Mike Harle, Keith, David, Bev Haberle and Allen McQuarrie were all there from Pennsylvania as well. It was before the focus on recovery really took hold and the slogan, I recall was “Treatment Works,” which was the early slogan of recovery month. It was actually around that time I realized that I had been in treatment. I had not really thought of outpatient in that way. It was more like getting connected to community for me. The slogan became “nothing about us without us” as we all began to come together and focus on recovery.

We were looking at how to establish recovery community affiliates, and Message Carriers became the western affiliate. There were some other people at the time running Message Carriers, one was not in recovery, another one struggled with his recovery. We started organizing rallies and events. One of those events was at city island in Harrisburg. We organized a bus from Pittsburgh and the guy who was supposed to lead it from Message Carriers failed to show up. Dona looked at me and suggested I lead it. At first, I was not sure I could. I was in school and had a lot to juggle. Dona convinced me. She also said she would help. When I had to come out to Harrisburg, she let me sleep at her place. There was a lot of support from within our community and things started to take shape.

- What did Message Carriers accomplish during its operation?

We organized the first recovery rally in Pittsburgh. It was around 2003 and is now known as Pittsburgh Recovery Walks. PRO-A would support ours; we would support theirs. We started to organize the recovery community of Pittsburgh. Over time, we found that our event became a county event and we found ourselves on the outside looking in. That happened more often than not over the years.

Another major success was our prison reentry program. We connected people coming out of the prison system with the recovery community. Nobody else was doing this back then. It took the recovery community to step up and serve our own people. We even had Jan Pringle of PITT PERU independently evaluate the program. She found what we were reducing recidivism by around 80%. The program we put together was successful, yet over time it too ended up moving away from our RCO. Others were funded to run it and we were not. It seems like we came up with many great ideas. When those ideas took shape, the money to do those things went elsewhere. At one point, someone in a position of authority openly acknowledged that our ideas were being used, but as implemented by others.

Message Carriers would put together events, like our Tree of Life event. When treatment organizations would put similar events together, their events got shared across the region. They were supported, but not our RCO. We were always told we needed to get more people involved, or some other excuse. We got lip service, not support.

We all came together in that era and put together the CRS training at PRO-A. It was PRO-A, PRO-ACT, RASE Project and Message Carriers who came together in the offices of PRO-A to set up the credential. It was one of the first in the nation and we began to train people, a major goal of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement. That was taken away too.

You helped me with one of those DDAP grant applications last year. We got a letter saying our submission was rejected. It was the last straw. Every door was shut in our face, time in and time out. That is how Message Carriers closed during a time when our state has more resources than at any other time in history. It was not a lack of resources that closed us. Not one dime got to us. How does that happen, exactly? In my heart, I think they really don’t want recovery community organizations to be supported, it scares them. One run by black people scares them even more.

So many meetings that we were asked to be involved in, but never a penny of support for our involvement. Actions speak louder than words. We were not valued. If we had been valued, they would have found a way to fund us. Since we did not fit in their little box we were consistently left out. It is no accident that that our Recovery Community Organization, Pennsylvania first and for a very long time the only African American run RCO was never really supported and struggled for years until it closed. It is happening to other groups as well. Not one single penny of government support for their work either. What do you think that looks look like to our community?

I became known as that angry black woman. It is true, I am angry about what I saw was being done to us, year in and year out. It was like we would pull things together and then a roadblock would appear. We would submit for a project and then be told we did not have a promise number, so we ended up out in the cold. Maybe next year it would be different we were told. It seemed like monies went to programs who were better politically connected in ways we were not.

They talk about stigma, but then marginalize us because they don’t want more than a media campaign by outside groups. They keep us at arm’s length and under control for a reason. What it looks like is that they only want to acknowledge things on the surface, they do not want to actually dig in deep and deal with it. That makes people uncomfortable. It should, but that does not mean we should not look at it. Message Carriers was killed off because that is what the system wants. It looks like they do not want a strong recovery community, they want control. Being in control of an outcome keeps our system comfortable even as our community members die. That is not okay.

It is like Critical Race Theory. We teach kids that there was slavery in this country, but the lite version. We don’t teach kids about how 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered by a group of white men because his presence in a grocery store upset a white woman. They lynched a 14-year-old boy, and those men ended up with no consequences from our justice system. That was 1955, and it still is happening now. We do not teach this because it makes people really uncomfortable. We know that in recovery, being uncomfortable is part of change. Meaningful inclusion can be uncomfortable for the system. Business as usual is killing our community members. That is an uncomfortable truth. We can’t heal in comfort.

Like Don Coyhis of White Bison once said, the system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets. It is designed for disparate funding and support for recovery community organizations because they do not really want “those people at the table.” Of course, I am an angry black woman. I am angry about what I have seen happen to us. I am angry that my community gets incarceration instead of treatment and we do not fund recovery support provided through recovery community organizations. I am angry that the deck is stacked against us. I am angry that Message Carriers was killed off, death by a thousand cuts. The question is not why I am angry, the question is who would not be if this is what was done to them?

- You have been a major contributor to the recovery movement in your region and beyond over your lifetime. What are you most proud of?

Day in and day out, we showed up to help heal our community, despite the barriers put in our path. Message Carriers was good at supporting multiple pathways of recovery. We have a strong faith-based recovery community in Allegheny County, and we pulled them together. We embraced MAT and the use of medication as a pathway to recovery. We embraced and included the 12 step communities. We brought in harm reduction strategies to keep our community members alive until they could find recovery. We helped our community find their way out of the criminal justice system. In the years I kept Message Carriers going, it touched a whole lot of lives. We helped people find hope and connection, and quite often that led to recovery. Despite our sad ending, Message Carriers has left a huge legacy of restored lives in our community. I want people to know that. I am proud of what we did.

- What would you want young people to know about what you have learned along the way?

It is really important for young people in recovery to study our history. What we have gone through and what we have had to do to accomplish what we have. They need to learn about what happens when we get divided up by those who want to diminish us. They need to learn that we need to focus our systems more on recovery if we want to heal our communities. I want young people to know that we can and do get better, and that the recovery community is vital to that process for so many people.

When one studies our history, there are many difficult times, but we keep moving until things get better. Despite all the barriers, we do get better and then things get better. I would want young people to know that we have to sustain hope for a brighter future. I would want them to know that our systems can and must do better, but for that to happen, we must be at the table in meaningful ways. Anything less is unacceptable.

- What feedback would you have for policy makers on supporting recovery moving forward?

Policy makers need to take a hard look at the system, acknowledge how broken it is and include us in redesigning that system. It must be acknowledged that not funding us is a form of discrimination, and then it must be fixed. The recovery community must have a meaningful role in where the money goes and what is done to heal our communities. We need to pay attention to where the money goes, because it is not supporting things that we need to heal our communities. And we should not have to do “go fund me” campaigns on social media to sit in rooms and participate by sitting at the end of a process once all the decisions are made on where millions of our tax dollars get allocated.

It feels like a bitter pill to me that we fought so hard to create and elevate recovery, believing that this would mean we would get more focus on healing our communities and then experience what I have experienced. Those kinds of things have to be acknowledged and fixed, and not in the way that it has been historically. They say millions of dollars are being spent on recovery, but we can’t see it.

Far too often these kinds of things get wallpapered over and they just move on, pretending there is not an elephant sitting in the middle of the living room. If I did not care, I would sit down, shut up and go about my life. I do care, and I cannot do that. To do so would be a betrayal of all those who came before me. We have come a long way, but we have a long way to go.

- What are your hopes for the next generation of recovery advocates?

It is my hope that they are going to be able to find ways to collaborate together and to not be pitted to fight each other for scraps of funding left on the floor once all the powerful groups get to carve up the lion share of the resources. I would hope that they realize we are being pitted against each other so that we can be kept weak. I want them to know that they have to support each other, or we all lose in the end. It is important for them to understand that we must be united, or we end up with nothing. We must stand together. If the next generation learns that and acts on it, they will accomplish a whole lot.

1. Hope matters in recovery

I’ve been musing a bit recently on the place of hope in addiction treatment and in recovery journeys. Researchers from the USA[1] identified that hope, although recognised as essential for recovery, was not well researched in terms of how it helps recovery progress. They used validated tools (questionnaires) to assess hope and recovery in 412 people. They found that progressing in recovery reduced relapse risk and that hope had a positive mediating effect.

Behavioural change or life transformation?

The researchers suggest that professionals “Consider adopting a holistic approach to addiction recovery that includes factors associated with wellbeing and human flourishing, as opposed to focusing solely on the managing of behaviours. By helping individuals develop a sense of self efficacy (i.e. mastering my illness), clarifying their values, and fostering feelings of connection and belonging, treatment professionals help individuals reduce the likelihood of relapse.”

They go on to stress how important these elements (self efficacy, values, connectedness) are to people who are new to recovery and how by highlighting these, professionals can strengthen their clients’ journeys toward recovery. Key to this is helping to frame recovery as a whole life transformation and not just a behavioural change. (My emphasis)

That feels like a quantum shift from how we come at things currently.

2. Abstinence goals may be more reliable than moderation goals

People asking for help for their drinking problems have a range of problem severities and a range of goals. Both things can be dynamic. Some folk want to reduce their drinking and others want to stop. Some, with severe physical or mental health consequences related to drinking will die if they continue to drink. When we research outcomes from treatment, we tend to look at outcomes that clinicians think are important and less at whether individuals reach their own goals.

In health terms, there’s a consensus emerging that no level of alcohol intake is completely safe, but for most modest drinkers, the risks are felt to be minimal. However, this is evidently not true for people with severe alcohol use disorders. Research has shown that the best treatment outcomes are achieved when people have set abstinence as an end goal, even if moderating drinking was the goal at the start of treatment. My experience from general practice for those with the most severe alcohol use disorders was that initially some – perhaps most – set moderation as a goal, but over a long period, even with maximum support, they moved towards believing abstinence would be safer.

For the kinds of patients I see seeking residential rehab who are at the far end of the severity scale, all have come to the conclusion that stopping drinking represents the best kind of reduction of harms. Many have tried to reduce or control their drinking over years and found that they could not do it in a sustained fashion.

In research[2] from the United States involving 153 people with alcohol use disorder, researchers explored what was going on in terms of the drinking goals the subjects set themselves daily – whether these varied and whether they were able to reach them. They found that complete abstinence was the commonest goal and the one most likely to be reached compared to those aiming for moderation. Paradoxically, they also found that when a daily goal of not drinking couldn’t be reached, those individuals drank more than those setting moderation goals. Nevertheless, the researchers point out:

Abstinence-based daily goals appear to lead to the greatest reduction in at-risk drinking and quantity of alcohol consumption overall.

Pavadano et al, 2022

They say their findings ‘support the clinical benefit of mapping daily goal setting and strategising for specific circumstances’. Of course, this is something mutual aid groups have been practising for decades.

3. Recovery – pulling is better than pushing

Recently I was asked whether getting bad test results (e.g. evidence of poor liver function from blood tests) could act as a motivator to help cut down drinking in someone with alcohol use disorder. I had to be honest and say that in the patient group I see, almost all of whom have biochemical evidence of livers under attack, this was not the case. I said that motivation for recovery generally has to come from hope that things can get better rather than fears that they will get worse.

It was interesting then to have my own observations bolstered by qualitative research[3] from Derby. David Patton, David Best and Lorna Brown explored the part the pains of recovery (push factors) and the gains of recovery (pull factors) play in recovery progress in 30 people with lived experience. Painful things identified included discovering unresolved trauma, difficult housing transitions, moving away from using friends, navigating a new self/world, hopelessness, family difficulties, relapse and stigma.

Pull factors in early recovery related to making new friends in recovery and gaining tools for recovery – mostly in the settings of mutual aid groups. In sustained recovery those ‘pull factors’ were things like: exceeding expectation of what life might be like, supportive romantic relationships, social networks, stable housing, family reconciliation, finding purpose and making progress in employment.

The researchers found that ‘the pains of recovery rarely led to positive changes’ and that those changes were promoted instead by ‘pull factors’.

Their bottom line:

As recovery is neither a linear pathway nor a journey without residual challenges for many people, there is much to be learned about effective ongoing management strategies in preventing a return to problematic use that utilize a push and pull framework

This confirms my impression that when it come to positive change that carrots are generally better than sticks.

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

References

[1] Gutierrez D, Dorais S, Goshorn JR. Recovery as Life Transformation: Examining the Relationships between Recovery, Hope, and Relapse. Substance Use & Misuse. 2020;55(12):1949-1957.

[2] Hayley Treloar Padovano, Svetlana Levak, Nehal P. Vadhan, Alexis Kuerbis, Jon Morgenstern, The Role of Daily Goal Setting Among Individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder, Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports, 2022,

[3] David Patton, David Best & Lorna Brown (2022) Overcoming the pains of recovery: the management of negative recovery capital during addiction recovery pathways, Addiction Research & Theory,

SMART Recovery is excited to partner with iConnectHealth to conduct a robust study determining the relationship between personality type and addiction problems, and to identify which factors may mediate that relationship. The research will also explore the potential benefit of matching mutual help groups and/or treatment orientation with personality types.

The practical benefits we see resulting from this study are an improved understanding of which personality types are attracted to and may benefit most from SMART Recovery, and a way to enhance facilitators’ ability to engage very different types of group participants.

As a thank you for participating, you will receive your individualized De-Stress Rx report which identifies your most powerful stress triggers, symptoms, and strategies for reducing stress.

We are looking to recruit as large a number of SMART Recovery members as possible.

Study participants:

- Must be 18+

- Take the online survey in English

- Have attended (or led) a SMART meeting in the last 30 days

We recently had the opportunity to interview Paul Tieger, Lead Researcher, about the study. He shared the goals and impact they want to make with this study. Click here to listen to the podcast. Click here to watch the webinar.

For questions, please contact: Lead Researcher, Paul Tieger, [email protected]

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Preface: I see a lot of change going on. Sometimes I like to take notes and get things down on paper in an organized way so I can clear my mind and try to make better sense of what I am noticing. This article is that. I share this writing for the sake of the idea that someone else might also be trying to make better sense of things as well.

My starting place is to back up to the idea of a helping relationship. A helping relationship consists of a helper and the one being helped. And that’s no different in the substance use arena.

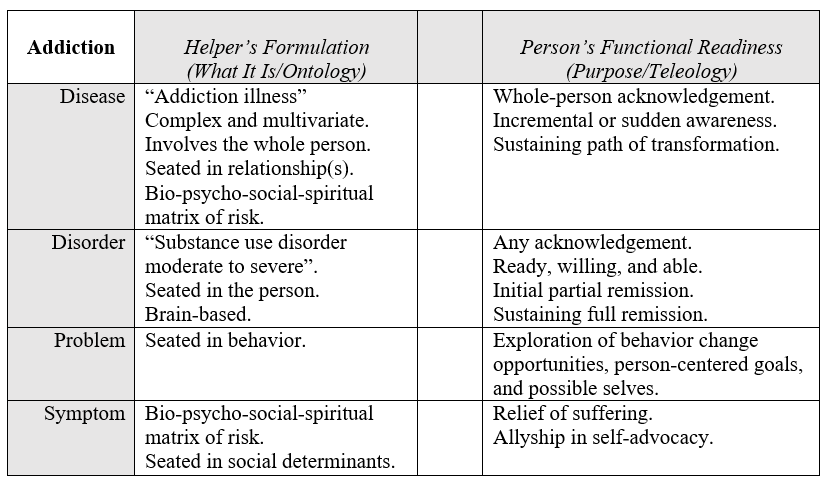

A helper in the addiction arena might view addiction as either a disease, a disorder, a problem, or a symptom.

Meanwhile, the one seeking help might be on a path of whole-person long-term transformation, or seeking total diminishment of their disorder, or exploring options concerning mitigating use, or wanting an ally in their struggles.

When the helper and the one seeking help meet, I wonder if their individual understandings and purposes are a relative match?

And I wonder if we as addiction professionals steer those seeking help and our colleagues accordingly?

Changes in Understanding and Purpose

During the last few decades I have seen an expansion of research and clinical commentary about the nature of substance use problems and their associated helping methods. One result of this expanding effort I have noticed is the development and clarification of differences in how substance use problems are viewed among and between helpers and those seeking help.

And in more recent years, I have seen a rather vastly expanded discourse in academic, research, clinical, public health, policy and other arenas concerning the formulation of what moderate to severe substance use disorders are. What is especially interesting to me is that this development and clarification of differences is within the distinct category of moderate-to-severe substance use disorders – what would otherwise be called “addiction”. That is to say, within the category or concept of addiction, large differences have come to exist in how that more severe and specific problem is generally understood.

Likewise, I have seen a rather vastly expanded discourse in the same literature (and other sources as well) about the purpose of help as expected by and for those who are seeking help.

These differences in understanding addiction, the help being offered, and the help being sought, exist among helpers/helping systems on the one hand, and among those seeking help on the on the other hand. And so naturally there may be a relative match or mismatch of understanding and help between the helper and the one seeking help.

Differences in Understanding and Purpose

Addiction may be understood in vastly different ways. And those seeking help may be ready in very different ways. What are some possible identifiers within these differences? And what recent examples have you noticed?

Below I lay out a framework that shows addiction understood as a disease, or a disorder, or a problem, or a symptom. And for each of those I organize the clinical formulation of the helper and the functional readiness of the one seeking help.

Although working on this was somewhat of an academic exercise, working out this kind of thing helps me at times to organize and clarify what I am aware of.

I’ll say a few things about some of the contents of that grid.

First of all, the open center column is supposed to hold the idea of “matching” like on a test in school. And it’s also meant to show the space within which the relationship happens. Really, what I have in mind is also “mismatching”, of course.

Another thing I wanted to clarify is that in my experience the clinicians that hold the disease model and those helpers more centered in social liberation are the most alike in one key way: the thoroughness of their general awareness.

Thus, I put “bio-psycho-social-spiritual matrix of risk” down for both of those views.

I say that as someone who was academically trained in hardline scientist-practitioner thinking, radical behaviorism, and cognitive-behavioral psychology. That is to say, I know all too well the comparative narrowness underneath the world view that sees addiction as a “disorder” or a “problem”. I will also say that as a result it is hard for me to be sure just how dispassionate I am in what I have included and not included in the grid, especially for the helper side of the “disorder” and “problem” categories.

The column on the right is about purpose, and I decided to add content in that column from the perspective of the person seeking help, rather than from the one providing help. I decided to do that in order to amplify the way a possible mismatch with the helper might manifest. And I decided to limit the content of that column to words centered in what that person might be seeking as well as their functional readiness. Far from complete, these are simple notes to help me clarify my own thinking.

Discontinuity

It occurs to me there may be a relative match or mismatch between the helper’s notion of what addiction is understood to be, and the purpose of the help as defined by the person seeking help. The space within the relationship of helper and person served may be improved or eroded by the fundamental assumptions each of them hold in this regard.

Further, the path or type of help sought by the one looking for help might shift, and this might improve or degrade the match over time.

Even more recently, COVID, various societal forces, and a significant increase in the USA of opioid overdose deaths seem to have collectively brought about a level of considering and reconsidering among many in our profession. And this has resulted overall in a relative stop, break, or discontinuity from the longstanding lineage, understanding, and historical context of our field.

I see the basic content, context, and lineage of understanding in our profession (as it has been seated in our historical continuity and shared in oral tradition, writings, and story) is eroding, And so, in the broader context of the professional part of our field, the former collective understanding of addiction and related helping is now relatively de-emphasized or removed.

And rather, at this moment in time, we are forming new ways of understanding and of helping that began and sit comparatively free-standing in time. It’s almost as if they were brought about and born in a space of discontinuity.

For example, the post-overdose response teams, needle exchange services, and overdose prevention efforts of today (as innovated in the current context) seem quite different to me from the needle exchange and prevention strategies I saw when I stated clinical work in 1988. And they have arisen very recently.

Forming Connections

I’ll leave the reader with some action items to consider that are framed as opportunities.

Rather than attempt to be all things to all people, we could remember to…

- …be more aware of emerging systems of help that are different or new.

- …be professionally and actively linked to newly emerging systems.

- …link helpers from other frameworks to those people they don’t know yet that work elsewhere within those kinds of spaces and kinds of help (so they can meet their peers).

Aside from the readings below, I’ll conclude by linking to an article summary; the reader might be introduced to a leadership style helpful in this context and worth investigating.

Suggested Reading

de Saussure, F. (1916, 1998). Course in General Linguistics. Open Court Classics: Chicago.

Levi-Strauss, C. (1958, 1974). Structural Anthropology. Basic Books.

We anticipate the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) treatment court grant solicitation will be released in the coming weeks.

Additional funding opportunities for treatment courts, law enforcement, prosecutors, behavioral health, corrections, reentry, and reform will soon be available.

BJA has scheduled several webinars to assist with your planning. Additional assistance can be found on the Department of Justice JUSTgrants resource page. Below are available webinars to assist with solicitations.

BJA Funding and Resources for Law Enforcement

This webinar will assist prospective applicants find funding opportunities focused on law enforcement. In this webinar, attendees will learn about the primary initiatives BJA plans to fund in FY22 that support law enforcement, along with eligibility requirements, examples of allowable uses of funding, estimated funding amounts, as well as training and technical assistance opportunities. A Q&A session will follow at the end of the presentation.

Thursday, March 10, 2022

3:30 p.m. – 4:30 p.m. ET

BJA Funding and Resources for Courts and Prosecutors

In this webinar, attendees will learn the primary initiatives BJA plans to fund in FY22 that support courts. Solicitation eligibility requirements, examples of allowable uses of funding, estimated funding amounts, as well as training and technical assistance opportunities will be highlighted. A Q&A session will follow at the end of the presentation.

Thursday, March 17, 2022

1:00 p.m. – 2:00 p.m. ET

Federal Support for Behavioral Health and Justice Responses: Best Practice, Resources and Education

This webinar will discuss behavioral health interventions and BJA resources that can assist with strategic planning and program implementation to address mental health disorders, co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders, substance use and addiction, criminal justice system responses, school responses, and responses to populations such as youth, tribes, and veterans. BJA funding, tools and resources that are specific to behavioral health will be discussed. A Q&A session will follow at the end of the presentation.

Wednesday, March 23, 2022

2:00 p.m. – 3:00 p.m. ET

BJA Funding and Resources – Corrections, Reentry, and Reform

In this webinar, attendees will learn the primary initiatives BJA plans to fund in FY22 that support jails, prisons, the community-based organizations they work with, and experts to support them. Panelists will review BJA opportunities, along with eligibility requirements, examples of allowable uses of funding, estimated funding amounts, as well as training and technical assistance opportunities. A Q&A session will follow at the end of the presentation.

Thursday, March 31, 2022

1:00 p.m. – 2:00 p.m. ET

Visit BJA’s Funding Webinars page for more information on upcoming funding events, and stay tuned for an announcement from NADCP on the release of the FY’22 solicitation.

The post Get Ready for BJA Funding Opportunities appeared first on NADCP.org.

Denial is a powerful thing. It can make us believe whatever we choose to believe, even though the fac ts stating otherwise may be right in our faces. Denial is an extremely common defense mechanism that our brain produces to help us cope with and rationalize stressful, traumatic, or unpleasant events and experiences in our lives.

ts stating otherwise may be right in our faces. Denial is an extremely common defense mechanism that our brain produces to help us cope with and rationalize stressful, traumatic, or unpleasant events and experiences in our lives.

Although everyone experiences the process of denial multiple times throughout their lives, it is even more common among those struggling with substance use disorder. Think back on times when you were in denial about your use, such as telling yourself that “just a little bit is okay” or “at least I’m doing better than that person.” Often, hiding behind denial was a way to falsely convince yourself and others that things were going well and there were no issues.

Denial can be displayed in multiple ways. Look at some of the most common denial methods and ask yourself if you remember utilizing them when you were in active use:

- Rationalizing: The “just a little bit is okay” mentality. When rationalizing, you tell yourself that you deserve a treat for completing particularly hard or stressful tasks. You believe that using is a justified and deserved reward to yourself.

- Minimizing: The “it’s no big deal” mindset. Making your struggle seem less difficult or intimidating and attempting to brush off fears and concerns. You may realize just how serious your problem is, but simultaneously deny its importance to yourself and others. “I’m only hurting myself.”

- Projecting: The “it’s not my fault” mentality. You project your issues onto other people, blaming them and focusing on what they’re doing wrong instead of what you’re doing right. An example could be placing blame on family or friends for causing you to use.

Now that you have seen and identified with common denial methods, you don’t have to feel bad or guilty. As stated previously, everyone is in denial at multiple points in their lives – and there are many ways to overcome denial, be honest with yourself, and process your emotions and reactions in a healthier way.

- Journaling: Writing down all your thoughts can provide a useful tool for soul-searching and emotional confrontation within yourself. It gives you a chance to let everything out, even your most private thoughts, so that you can be more honest with yourself, and the process of healing can begin.

- Expressing yourself: Don’t keep everything bottled up – speak your mind to others, tell your truth, and be willing to have difficult conversations as a result. Keeping all your feelings hidden can lead to resentment, guilt, or anger, and these negative emotions usually result in denial.

- Attending meetings: By regularly going to AA or NA meetings and keeping in touch with a sponsor, you will be surrounded by a support group of people who are dealing with the same problems as you. You can be completely truthful with them, and they will be able to hold you accountable.

Denial can be tricky and scary but overcoming it can be as simple as surrounding yourself with trustworthy, supportive people and opening up. Living an honest life and dealing with your emotions head-on is a path to successful, sustained recovery.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

Disclaimer: nothing in this post should be taken or held as clinical instruction, clinical supervision, or advisory concerning patient care.

Spiritual care is a clinical discipline.

- Spiritual care can be a clinical team member in the separate settings for physical health problems, psychiatric problems, or substance use disorders.

- And spiritual care can be a member of an interdisciplinary team treating co-occurring conditions.

The simple proof of the reality of this is seen daily in the routine work of systems that include spiritual care in their interdisciplinary process. But there is one example I would like to show you, and this example might reveal a way to better utilize spiritual care even where it already exists and is integrated.

Imagine a treatment team in a residential addiction treatment program serving those with co-occurring psychiatric conditions. And imagine that the treatment team consists of primary health clinicians, nurses, addiction counselors, clinical psychology, spiritual care, and a physician specializing in psychiatry. And the team is reviewing how each patient is doing.

The team leader asks, “How is (name of patient) doing?”

The assigned counselor says, “Good.”

After a moment, a nurse calmly states, “Not good.”

The team leader says, “Oh?”, as if to ask for more information.

The nurse says, “They’re not taking their medication for their bipolar disorder.”

To which the team leader then asks aloud to the team, “How do we understand this?”

The nurse adds, “They don’t believe in it. Neither do their parents.”

After waiting and hearing no other input, the team leader then asks, “What’s our plan?”

And at that point a pause in the team process ensues and an extended silence is held. The silence is finally broken by the Spiritual Care team member who speaks directly to the prescribing psychiatrist, saying “Here’s the open door…”

And spiritual care then provides person-specific coaching to the prescriber in understanding the basic cosmology of the patient in real-world matters. And quickly coaches the team and its members in identification and use of an open door in the patient’s world view.

And we now return to our scenario.

Prescribing psychiatrist: “Great. Thanks. I’ll be speaking with the patient and the family.”

Team leader: “Any other inputs to our plan?”

And hearing no other needed inputs to the plan, the meeting moves on.

In this way, spiritual care contributed to patient adherence to the plan.

Some systems limit spiritual care to the support of patients and family members in times of crisis and end-of-life matters.

In doing so the system seems to function as if the basic bio-psycho-social-spiritual nature of all people is not understood. And that the simple value of spiritual care in all care is not understood.

Rather, it’s almost as if the “inter-disciplinary treatment team” is not about the person as a person, but is rather:

- built by clinicians centered in their clinical identities

- all about the mix of clinical disciplines that are present

- centered in the disorder.

It’s almost as if “inter-disciplinary” does not start with what a human being is in the first place (a bio-psycho-social-spiritual being). And thus, the team is not formed in a way to include those 4 components of a person.

If any of this is accurate, does it matter, and is it practical?

In the industrialized medicine environment of today:

- there is so much attention paid to the “work relative value unit” of each clinician’s every working minute

- there is great attention paid to squeezing out maximal precision and accuracy

- there is great strain to find what is “effective, efficient, necessary, and sufficient.”

And that environment of today leaves me amazed that:

- patient adherence to any plan for any condition is not improved by applying spiritual care from the bottom up in routine care

- spiritual care is not applied to understanding every patient with every kind of condition (especially chronic conditions)

- systems often believe that the way to improve patient adherence is by adding a top-down organization-wide mandate that everyone in every discipline across the system must learn and implement some aspects of motivational interviewing and doing that will “work”.

Suggested Reading

Goodheart, C. D. & Lansing, M. H. (1997). Treating People with Chronic Disease: A Psychological Guide. American Psychological Association.

Recovery journeys can be long and involve several attempts in order for people to resolve their problems. Treatment can be part of this for many, but there are multiple factors outside of treatment that also influence outcomes. One of these is housing.

Homeless people with substance use disorders have higher risks, exacerbated further if there are criminal justice issues. Recovery housing can provide a safe environment, support for abstinence and link people into education and employment opportunities. If houses are self-run, costs are low.

In their paper[1] on sober living houses, Jennifer David and Jake Berman point out that it’s only relatively recently that researchers have begun to accumulate evidence on the efficacy of such residences. I agree; we have some black holes in our research on substance use disorders and recovery. There are a few of these residences in the Scotland, but little is known about them beyond experience and evaluations accumulated locally.

By using the narratives of residents, the researchers wanted to explore the experience of being in a sober living house from the perspective of the people in recovery. They interviewed 21 people (from the American Midwest) – so a small study, but the point was to find detail and nuance.

Out of this came four themes.

- The role of early trauma

- The strengths of sober living

- The challenges of sober living

- Keys to sobriety

The role of early trauma

Residents related the impact of trauma and how it shaped their journey into addiction. This took many forms and the researchers note how abuse of drugs and alcohol were identified as both the cause and consequence of trauma. During the interviews, the salience of these experiences was apparent, as was their emotional impact on the respondents in recovery.

The strengths of sober living

The study participants were ‘overwhelmingly’ positive about ‘the impact of sober living on their lives and on their recovery up to this point’.

Sober living opened my eyes that others have the same struggle. I learned to open up. I’ve made friends for life.

Participant

Safety, shared goals and vision, unity and camaraderie were all found to appeal to the residents as advantages of sober living. Stigma and shame became less powerful and the group looked out for each other.

Everyone sticks together. If one of the sheep starts straying away the herd goes and rounds him back with the rest.

Participant

Mutual accountability was ‘an important driver of behaviour’ with a sense of responsibility for others being highlighted as key. This struck me as being very similar to living in a therapeutic community model of rehab. The principles are comparable.

The challenges of sober living

Those who were not ready to put the work in (in recovery terms) were felt to have a detrimental effect on others. The threat of relapse was a ‘critical challenge’. When others relapsed there was a vicarious suffering as the bonds that develop in a communal living houses can run deep. Dealing with death was also spotlighted as a difficult challenge.

Some saw the sober house as ‘an artificial environment that protects residents from the real world’, and others saw it as ‘a transition rather than a protection’.

Keys to sobriety

The importance and value of attending mutual aid (AA) was mentioned in all the interviews, as was changing social networks and taking advantage ‘of the protection of sober living.

Reflections

The researchers identify the tension between the emergent benefits of sober living, versus the potential risk that being in such an environment may hold some people back from learning skills in the community. They call for more research on such transitions. They also emphasise the advantages reported by the residents of being members of AA. Reflecting on their findings on trauma in the interviewees, they speculate on whether there may be a ‘unique practice niche’ that deals with early trauma through a more targeted therapeutic approach in addition to being mutual aid group members. They also suggest we need to know more about ‘vicarious relapse’ which can be traumatic to others as well as the person who has relapsed.

Although a small study, the findings ring true from my experience. In the service I work in, our Oxford recovery house has evaluated well. Having said that, this whole area is very under-developed, with little in the way of recovery housing being commissioned (or even known about), though there is evidence that this is changing a bit for the better.

As stronger and stronger evidence emerges of the value of community and connection as drivers of recovery, I hope we see more of this kind of practice and research in the UK. It’s certainly needed.

Continue the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

Photocredit: istockphoto sundaemorning under license

[1] Jennifer Davis & Jake Berman (2022) Living in a Sober Living House: Conversations with Residents, Substance Use & Misuse, 57:3, 402-408.

“Nothing happens. Nobody comes, nobody goes. It’s awful.” ― Samuel Beckett

We have never had a care system that provides people who need help with addiction the resources they need to heal. For me, one of the most poignant lessons in how hard it is to get people what they need to heal happened with PA Act 106 of 1989. Other states had done similar laws before we got around to putting one on the books here in PA. This occurred because some people decided to stop waiting. Once passed, the insurance industry here in PA largely ignored the law for many years. A lot of people died. I knew some of those who did. Families testified in front of our legislature and went to court to get the insurance industry to follow the law in respect to residential treatment. It went all the way to the State Supreme Court, who upheld a lower court decision affirming the law in 2009. It took action, not waiting.

For those who worked on this one facet of the law followed, it was a Sisyphean process measured in decades. It took a generation to get at least 30 days of care for the people whose insurance plans are covered by this law, which does not specify a maximum number of days. Neverminded that the NIDA has long noted that 90 days is the minimum dose of effective care for an average SUD. Almost nobody gets that with private insurance in America! Other elements of the law, including mandated family counseling and intervention services do not appear to be adhered to as I sit here today and write this. 33 years later, and we are still waiting for Godot. Even as our loved ones die. It is an outrage. Can you imagine if this was some other condition impacting one in three families and having this happen?

We keep waiting. As the Beckett quote above notes, nobody comes, nobody goes, it is awful. Seven years ago, I was part of a process in PA looking at barriers to SUD care that occurred as a result of a bipartisan effort to examine access to addiction treatment through health plans and other resources under the PA House Resolution 590 of 2015. We did just that, holding hearings across the state and listening to the community. As a taskforce, we recommended in this report that “health plans provided by employers to cover substance use disorder treatment, should identify that they are in fact subject to Act 106 on an individual’s insurance card to assist consumers and providers in efficiently accessing those services. The information provided to Pennsylvanians covered by Act 106 plans should delineate all services available including family and intervention services.” People cannot access a benefit that they do not know they have.

Yet, It is still not done seven year later; in the midst of the largest addiction epidemic we have ever faced, we cannot seem to get lifesaving information on the back of our insurance cards. Thousands of lives and tens of million dollars of public resources could have been saved if families knew that their insurance companies were legally required to offer these services by seeing it on the back of their insurance cards. Somehow, we miss such huge and simple opportunities to save lives and resources in ways that end up being measured so tragically. Our families deserve better.

Somehow we still do not have this life saving information on Pennsylvania insurance cards. I think it belongs there! I suspect a lot of families struggling with an addicted family member would agree if they even knew they were mandated under many insurance plans by this law. Family counseling and intervention services can get people into care earlier and help in the recovery process. The authors of Act 106 knew that when they wrote it into the law so many years ago. Let’s make sure every Pennsylvanian family who is eligible knows about this benefit. Those who have died no longer have a voice, they are counting on us. Let’s get it done in their names!

I do see a sliver of light on the federal side, perhaps we may not have to wait quite so long for our federal law to be enforced as in our state. Under the leadership of US Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, the highest government official in US history to be a person in open addiction recovery, we have finally focused on enforcing our national parity law with some vigor. Three weeks ago the US Department of Labor released this report to Congress. This is the most significant effort to enforce this federal law in the 14 years that the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA) has been on the books. We can help by reporting concerns with our benefits by contacting the US Department of Labor about parity compliance at askebsa.dol.gov or by calling 1-866-444-3272.

What the report to Congress found was sadly predictable for those of us in the trenches. “Every plan and issuer that the EBSA (Employee Benefits Security Administration) sent a request to initially responded with insufficient information. “About one-third of those requests resulted in initial determinations of noncompliance.” This translates to thousands of families not getting the care that is required by federal law. According to the report, most of the companies audited had not even considered if they were in compliance with this 2008 law until they were audited.

Some of the report points that stuck out to me:

- Too often, plans had not completed or started a comparative analysis until after EBSA requested one. In some cases, the plans had imposed barriers for years without analyzing compliance with the law.

- Approximately 40% of plans and issuers responded to EBSA’s initial request letter with a request for an extension of time to respond. This suggests that had not bothered to look to see if their plans were in compliance with the law.

- One of the entities reviewed had impermissible limitations in the form of MH/SUD continued-stay criteria requiring demonstrable progress for continued care coverage, as well as MH/SUD discharge criteria resulting in a loss of coverage if there was no significant improvement in their care or if they left against medical advice.

- A large, self-funded plan, with 7,600 participants, specifically excluded methadone and naltrexone as treatment.

As I was absorbing this report to Congress, I ran across this article on Vox news: Her son died after insurers resisted covering drug rehab. It tells the all too familiar story of a mother, Maureen O’Reilly who thought she had good insurance coverage for her son, Ed Fahy. He kept being denied the proper level of care he needed. He ended up getting stuck in the “Florida Shuffle” of patient brokering. According to the article, independent reviews found he did not get the right level of care. He died of a cocaine and fentanyl overdose in a Florida recovery house. The article notes that her insurance companies had run into trouble with the parity act discussed above. Mr. Fahy ran out of time. She is now suing the insurers after a host of denied care. Hopefully it will help save someone else’s son or daughter.

So many of us in this field see these types of stories year in and year out. Ignoring laws and denying care is a cost of doing business for far too many of these companies. Here in PA, perhaps someday we will get the insurance cards that identify that the insured are protected by a law passed when I was just 24 years old. It should have been easy, but it seems not. We should not continue to wait in the trenches for Godot. It is a time of action.

The only way that this story ends differently than Beckett’s play is if we stop waiting for Godot.

Joseph Simon is grateful every day in his journey to recovery, for SMART and the tools to help him make the best healthy choices and live his Life Beyond Addiction.

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!