Angie Chaplin feels a sense of pride every time she facilitates a SMART Recovery meeting. Pride in knowing that the tools and resources that have helped in her recovery are also helping others in theirs.

Learn more about becoming a SMART volunteer

Find Angie’s SMART Recovery meeting

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

As we enter the third year of battling the COVID pandemic and having to readjust our lives, a lot of us may be starting (or continuing) to get agitated, stressed, and anxious. We may begin feeling like things will never get better and that we should just give up. It’s certainly not easy to reframe our entire way of life to navigate a pandemic while in recovery, especially when so much of a successful recovery is owed to constant connection and communication with support networks around us. However, while difficult, it is not impossible to be strong and healthy in your recovery no matter the world’s circumstances.

As we enter the third year of battling the COVID pandemic and having to readjust our lives, a lot of us may be starting (or continuing) to get agitated, stressed, and anxious. We may begin feeling like things will never get better and that we should just give up. It’s certainly not easy to reframe our entire way of life to navigate a pandemic while in recovery, especially when so much of a successful recovery is owed to constant connection and communication with support networks around us. However, while difficult, it is not impossible to be strong and healthy in your recovery no matter the world’s circumstances.

We can begin to fight our negative thoughts and desires to return to use by continuing to prioritize staying connected to others, whether virtually or in-person – but we also need to realize the effect our personal ways of thinking can either harm or help us on our journey to recovery. With constant work taking place both outside and within ourselves, recovery becomes much easier to manage.

Practice Acceptance:

“Acceptance is the answer to all my problems today. When I am disturbed, it is because I find some person, place, thing, or situation—some fact of my life—unacceptable to me, and I can find no serenity until I accept that person, place, thing, or situation as being exactly the way it is supposed to be at this moment.” – pg 417 of the Big Book

The oft spoken phrase around the rooms is “practice acceptance”. While it may sound trite, it is the key to serenity. Pushing against our reality, refusing to accept our reality, this is the source of much friction and unhappiness. However, that pushing, and that refusal is what comes most naturally to an addict or alcoholic. We must constantly remind ourselves of acceptance, and if necessary, repeat the phrase, “Acceptance is the answer to all my problems today”.

Prioritize Connection:

In today’s world, it has become increasingly difficult to stay connected and avoid feelings of isolation. This has led to relapse and overdose for many of those in recovery who slowly begin to feel anxious, lonely, and unsupported over time, slipping back into familiar patterns of using to cope. We may recognize the importance of attending meetings and staying in touch with a sponsor, but when many meetings are happening online, it is easy to feel “Zoom fatigue” and simply stop attempting rather than adjusting and making virtual connection work for us.

It takes a little extra work on our part, but we must be willing to challenge our beliefs about online meetings. Continue participating and sharing in your meetings, even if they must be via computer screen for the time being. The meeting space is not only for you – you must be there to support the others in your recovery network.

Avoid Complacency:

When someone in recovery leaves treatment, they can sometimes find themselves on a “pink cloud” of euphoria: proud of what they have achieved, connected to a support network with a sponsor and daily meetings, and strong in their sobriety. After a while, some of us begin to feel that maybe we have our recovery under control. We might think we’ve achieved ‘fully recovered’ status and do not need to continue dedicating as much time to our recovery.

Coupled with the collective anxiety and isolation felt during a pandemic, it can become easy and comforting to convince ourselves that it would even be okay if we had a drink or two, after being in recovery for several months or years. However, one can never truly be ‘fully recovered’ – recovery is a constant process, and becoming overconfident leads to complacency, which can lead to relapse.

“If nothing changes, nothing changes”:

In the popular A.A. book As Bill Sees It, written by Bill Wilson, the argument is made that successful recovery is simply not possible unless we are willing to undergo a personality change. Wilson writes: “anyone who knows the alcoholic personality by firsthand contact knows that no true alky ever stops drinking permanently without undergoing a profound personality change.”

This means understanding that having supportive people around you is not enough – there needs to be a change inside of yourself as well. Wilson continues: “We thought “conditions” drove us to drink, and when we tried to correct these conditions and found that we couldn’t do so to our entire satisfaction, our drinking went out of hand, and we became alcoholics. It never occurred to us that we needed to change ourselves to meet conditions, whatever they were.”

Outside conditions may produce triggers and negative feelings, but we have to be willing to work to change our responses to these conditions, because remaining stagnant and leaving our mental health unchecked is an easy gateway into relapse.

In a pandemic society, the traditional post-treatment advice – go to meetings, keep in touch with your sponsor, give back to your community with service work – may sound harder to follow. However, there is always a way to keep pushing forward and make recovery work for you, no matter your outside circumstances. Resist becoming complacent in your recovery. Keep recovery at the forefront of your mind and know when to ask for help. Show up for those in your network that are experiencing the same struggles as you. Together, we will be able to make the ‘new normal’ work and ensure the successful recovery of us and those we care about.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

SMART Recovery is excited to announce that the SMART Recovery Mobile App is now available for free download for Apple and Android phones everywhere.

Our designers, programmers, coders and UX team integrated everything they learned from our volunteers and beta testers to create a mobile app that’s easy to use by anyone, at any stage of their SMART Recovery journey.

After you download it, you’ll be met with a list of inspirational quotes that motivate and inspire. Then you can find meetings wherever and whenever they suit you. Add them to your calendar, click on zoom links, join meetings with just a tap; everything happens right there on your phone.

No more looking for content and toolkit exercises through websites, YouTube pages, or multiple podcast platforms. All of SMART’s content is now surfaced and viewable in one place through the app – with easy-to-navigate play buttons, crisp layouts, and enterprise-level playback and buffering speeds.

In a world where 90% of the apps on your phone rarely even get opened, we believe we’ve designed an app that you’ll want to open and use every day. As time goes on, we’ll make improvements, issue updates, and add new features, all with an eye toward giving our SMART Recovery community the highest quality mobile app experience possible.

Ready to go? Just click on one of the buttons below to download the app and get started. Don’t forget to tell your friends and colleagues in recovery about the app so they can get started too.

The SMART Recovery Mobile App is an important milestone in our continued efforts to provide the highest quality services and accessibility in the digital age.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Dr. Ashley Grinonneau-Denton is the founder and co-owner of Ohio Center for Relationship and Sexual Health in Cleveland, Ohio. She has a doctorate in marriage and family therapy and is a certified sex therapist.

In this podcast, Dr. Ashley talks about:

- Being one of only 16 people certified in sex therapy in Ohio

- The social and cultural aspects of Valentine’s Day

- Not marginalizing sexual background of clients

- Creating a sex positive environment

- Behaviors involved with couples and their sexual health

- Looking at all sides of an issue to see the client’s whole self

- Her soapbox about labels

- Getting to a healthy sexual life

- How the intimacy conversation is changing with each new generation

- The form and function in music and pop culture

- Conducting virtual consultations (even before the pandemic)

- Seeing co-occurring behaviors in clients that are making it harder for them to change

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Therapeutic nihilism

“None of them will ever get better”, the addiction doctor said to me of her patients, “As soon as you accept that, this job gets easier.”

This caution was given to me in a packed MAT (medication assisted treatment) clinic during my visit to a different city from the one I work in now. This was many years ago and I was attempting to get an understanding of how their services worked. I don’t know exactly what was going on for that doctor, but it wasn’t good. (I surmise burnout, systemic issues, lack of resources and little experience of seeing recovery happen).

Admittedly, a part of me recognised an echo of the sentiment. I’d worked for many years in inner-city general practice and back then, to be honest, I did not hold out as much hope as I might have for my patients who had serious substance-use disorders. After all, the evidence in front of my eyes suggested intractable problems. All of that changed when I began to connect with people in recovery and started to understand the factors that promote it.

Palliation or something better?

I don’t think my colleague’s perspective was (or is now) the predominant view, but by no means is it unique either. An addiction specialist has fairly recently urged us to accept that some ‘do not have the luxury of recovery’, seeing it as ‘a convenient concept, but an unobtainable reality for many people who use drugs’, who are really in ‘palliative care’. I struggle with this perspective. Some would say it’s realistic. I think it’s pessimistic.

Of course, there are people whose chances of resolving their problems and going on to achieve their goals remain low despite support, but who gets to choose who gets ‘palliation’ and who gets something better? We don’t start out with palliation as a goal of cancer treatment; why should addiction treatment be any different? If our treatment offer is focussed on palliation and only the few – the worthy and fortunate – get to go further, we are letting people down badly. Professor David Best has pointed out that this sort of therapeutic pessimism is a major barrier to the effective implementation of a recovery model.

My assessment in my visit to that MAT clinic was that I could not work in a service where views like that, for whatever reason, had become acceptable and explicit. However, rather than be defeated, I found instead that this provoked an energy within me to try to make a difference. That one incident, perhaps more than anything else (save my own experience of treatment and recovery), drove me to set up the service I now work in.

The clinical fallacy

While therapeutic pessimism undoubtedly exists, I am buoyed up by my past experience of working in teams in community settings where expectation of what is possible is much higher. I can think of many colleagues who set the bar high every day in their work, even when they are working in demanding circumstances.

While despairing and cynical views are not the norm, it is apparent though, for whatever reason, that some working in the field don’t hold out as much hope as they might. I’ve heard enough reports from individuals who feel they were discouraged or blocked from moving on towards their goals to know that it happens too often.

This nihilistic view of the potential of individuals to resolve their problems and move towards their goals can be explained to some degree by something Michael Gossop called ‘the clinical fallacy’. This is the situation in which the clinician sees all of the challenging presentations and relapses, while the people who resolve their problems move out of treatment and are not seen again.

The clinician is confronted continually by their failures and denied the benefit of seeing their successes.

Michael Gossop, 2007

This may explain findings from elsewhere which show that we professionals working with people who have substance use disorders consistently underestimate what our clients/patients are capable of. This is important. The clients of clinicians who are more positive do better[1] and conversely negative or ambivalent attitudes in professionals are linked to higher risk of relapse.

Professor Best, interviewed by William White in 2012, referred to work he’d done in the UK, scoping out the aspirations of addiction workers for their clients. He had asked them to estimate what percentage of the people; they were working with would eventually recover. The average answer was 7%. Evidence actually suggests that over time most individuals are likely to recover. However, if I believe your chances of recovery are only 7%, then I’m instantly holding you back because of my own beliefs and behaviours – conscious and unconscious. My bar is set way too low.

An Australian study found that practitioners there were more optimistic believing that a third of people with a lifetime substance dependence would eventually recover. But this is still an underestimate.

In general, it is fair to say that SUs [service users] look for tough criteria to define ‘being better’ – perhaps tougher than their practitioners.

Thurgood and colleagues, 2014

Raising the bar

Eric Strain picked up this theme of aiming too low in a recent editorial in the journal Alcohol and Drug Dependence when he wrote:

The substance abuse field in both its research as well as treatment efforts is not giving due consideration to flourishing. We need to renew our efforts to give meaning and purpose to the lives of patients.

Eric Strain,

Saving lives and reducing harms rightly need to be our first concerns, but is there a danger that we stop right there because we see the risks of our patients or clients going further as being too high? This week I was talking to an experienced addiction psychiatrist, now retired. He told me that early in his career he gave up trying to predict who was going to do well and who was not. He’d seen people, ostensibly with little going for them, get better from what looked like intractable problems. He’d seen others with a great deal of recovery capital die from addiction, despite the best efforts of family and professionals to support them. It’s hard to make predictions perhaps, but not too hard to hold out hope for everyone.

The necessity of hope

There are actually reasons to be more optimistic anyway. As I say, long term follow-up studies and retrospective studies of people in established recovery suggest that most people can expect long term resolution of their symptoms although this can take some years and several attempts during which we need to focus on keeping things as accessible, supported, and safe as possible, underpinned at all times by hope that things can and will get better.

So what of hope? Hope can be described as an emotion, a cognitive process or a positive anticipation which helps to motivate goal-oriented behaviour. However we define it, it is essential for recovery from substance use disorder, yet it features little in textbooks, guidelines and academic studies.

The patchy availability of hope in ourselves, our services and our service users does need to be addressed. Hope is a catalyst for moving forward. Academics have found that positive expectancies, like hope, predicted higher levels of resilience against post-traumatic stress symptoms. Other researchers have identified the critical role of hope in terms of survival.

The inclusion of hope in clinical practice shows considerable promise. Individual, group, and family therapy interventions that incorporate hope theory have been found to reduce symptomology and mediate recovery from various psychological and psychosocial conditions

Gutierrez & colleagues, 2020

It is apparent that hope is a necessary ingredient, not only for patients/clients to progress, but for professionals too if we want to be effective in supporting individuals towards their aspirations. I’m not suggesting we come at this with an unrealistic Pollyanna bent. Without manageable caseloads, support from colleagues, good clinical supervision and adequate resources – including joined-up care – compassion fatigue can set in and the therapeutic relationship can suffer. Hope, though vital, can ebb away.

“We must address issues around staff burnout, which I suggest is related to repeated exposure to client relapses without parallel exposure to clients in long-term recovery.” David Best, 2012

Prof David Best

The introduction of hope

In that conversation with William White, David Best encourages us to ‘inspire belief’ through a variety of interventions::

“The interesting issue for me is much less about what particular therapies and modalities we offer and more about whether we can inspire belief that recovery is possible, establish a partnership between the client and the worker to facilitate that change, mobilise recovery supports within the client’s natural environment, and link the client to those community resources.

We also need to locate recovery within a developmental perspective that recognises the lengthy (and non-linear) journey that most people experience in recovery. This means there are plenty of opportunities for a diverse array of interventions and also that people will evolve in their needs and their resources as the recovery journey progresses.’

Lived experience and hope

Structurally, the goal must be to create recovery-oriented systems of care, but within our existing services, there is a straightforward way to infuse hope. We can do that by embracing lived experience and introducing it into what are normally professional settings. Connecting those we work with to others in recovery stimulates aspiration. It’s true that some professionals are resistant to this concept, but people with lived experience can be involved in treatment settings, acting as role models and beacons of hope to everybody’s advantage – staff and patients. They can also bridge the gap between treatment and recovery communities.

In a local evaluation of a peer support model introduced into a harm reduction service, benefits to the service users were apparent, with greater levels of engagement and a high approval rating of the intervention. What was unexpected though was the benefit to members of the staff team. Because they normally worked with people at a much earlier stage on the recovery journey, the staff were not used to seeing people who had moved on from their problems. That experience of working alongside people who self-identified as being ‘in recovery’ changed the beliefs of the team, raising expectation and hope.

In a study[2] published this month which looked at the feasibility, accessibility and acceptability of peer navigators in roles that aimed to reduce harm and promote recovery (wellbeing, quality of life and social functioning), the researchers added to the growing evidence base that peers with lived experience can positively influence not only the reduction of harm, but also improvements in quality of life through various mechanisms including role-modelling.

Many participants also described less tangible but nevertheless important changes, including increased confidence and hope.

Parkes and colleagues, 2022

This was not all plain sailing, but staff noted how the peer navigators were able to spot things that staff didn’t, had tenacity with clients and could engage more ‘chaotic’ or ‘hard to reach’ clients.

What’s lovely about this open-access study is how easily the lessons can be adopted into practice. There are issues to be tackled and more work needs to be done on capturing outcomes, but this has the opportunity for us to tackle therapeutic nihilism within ourselves and within our services.

Recovery champions can convey the possibility that things can be different and offer living proof of that difference in their own lives.

Prof David Best

Generating hope

Peers with lived experience don’t just have the potential to introduce hope. Research also suggests that peer contact can help to reduce stigma. Visible recovery is generally inspiring, though some may be threatened by it. There is mostly a contagiousness about it which generates hope. I wonder if my colleague working in that challenging MAT clinic who came to believe that nobody would ever get better would have avoided therapeutic nihilism if she were buoyed up by working daily shoulder to shoulder with those with lived experience.

When we see burnout, despair and therapeutic nihilism we need a compassionate response, but more than this, we need to transform situations where hope has atrophied. Moving to peer support models in every treatment setting is surely an effective way to generate hope, not only in those who use our services, but also in ourselves.

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

[1] Simpson. D., Rowan-Szal, G., Joe, G., Best, D., Day, E., & Campbell, A. (2009). Relating counsellor attributes to client engagement in England. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36, 313–320.

[2] Parkes T, Matheson C, Carver H, Foster R, Budd J, Liddell D, Wallace J, Pauly B, Fotopoulou M, Burley A, Anderson I, Price T, Schofield J, MacLennan G. Assessing the feasibility, acceptability and accessibility of a peer-delivered intervention to reduce harm and improve the well-being of people who experience homelessness with problem substance use: the SHARPS study. Harm Reduct J. 2022 Feb 4;19(1):10.

Forward – I have known JohnWinslow for the better part of twenty years. I kept running into him in DC and in my travels around the country. He is a person in long term recovery for over 46 years, and he has been in the field of helping people recovery for the vast majority of those years. His work as a recovery advocate has taken him to the White House (twice). He served at ground zero at the World Trade Center after the September 11th 2001 attack to support police and firemen during the recovery efforts. He has taught collegiate course on addiction, presented at the FBI Academy, served as President of the Maryland Addiction Director’s Council, and had the opportunity to open one of the first Recovery Community Centers in Maryland – the Dri-Dock Recovery & Wellness Center.

Over the years, John and I have had many an opportunity to break bread together at conferences and meetings around the country. He is a friend and a person I have found who is filled with recovery wisdom and a lot of insight into our history and the recovery movement. Recently, John announced his semi-retirement, and that Faces & Voices of Recovery was going to assume responsibility what is perhaps his greatest gift to the recovery movement, International Recovery Day. Knowing some of his history and contributions to the recovery movement, I asked him to do this interview. I am grateful he agreed to it!

Tell us about yourself and your work to support recovery over your lifetime

First and foremost, I am a person in long term recovery, I got into recovery on January 21, 1976. I was in my 20s. But one of the things that was part of my story years earlier than that was that my older sister was killed by a drunk driver when I was 17. She had been 19 at the time of her death. The intoxicated driver who crossed the center line was killed, my sister and others in the car he hit also died. It was devastating. I vowed never to drink and drive again. It is a testament to how strong a pull addiction can have. That vow only lasted only a few months. I drove intoxicated many times in those years, despite the loss of my own sister. I experienced a lot of consequences, and in my mid-twenties I started to realize that my addiction was probably going to ruin a relationship I cared a lot about. In 1975, I voluntarily admitted myself into the psychiatric unit a Perry Point V.A. hospital where I spent two months under my veterans’ benefits, having served during the Vietnam era. I recall that they suggested I may be an alcoholic and sent me to a 12-step meeting. At that time, I wanted nothing to do with any of it.

About a year later, I was experiencing increased difficulties due to my substance use, and it began to threaten my job- which happened to be working with munitions at Aberdeen Proving Grounds. Substance use and explosives are not a good mix! I had been coerced into receiving treatment through my employer (the federal government) at an outpatient program. Eventually they told me I needed more than they could provide. This time, they sent me to Caron Foundation, which at the time was called Chit Chat Farms. I was filled with despair, I felt defeated and alone, but following a head-on collision while heavily intoxicated I experienced a “moment of truth’ and became open to help in that moment. I had just turned 26 years old.

The Caron Foundation provided excellent treatment. The program made sure I had a sponsor and a connection to my local recovery community before I walked out of the door. They had warm handoffs in 1976! That was one of the things that saved my life. Some of my counselors in this era had very little formal education but had an amazing grasp of addiction and recovery, and were highly skilled at communicating about what I was experiencing and what I needed to do to get well. I am grateful for what they did for me.

In early recovery, I started to think about what I wanted to do with the rest of my life, and the idea of getting involved in helping others find recovery was something that really appealed to me. I took a job as a night counselor at Springfield State Hospital and enrolled in classes to become an addictions counselor, which at the time were known as “paraprofessionals.” I realized that there were very few people in my age group working in the addictions treatment field and I thought it would be valuable to serve as a power of example in showing others -particularly young people – that recovery was not just possible but could be a reality for folks of any age (young or old) struggling with addiction.

The Springfield Program for Addiction Recovery (SPAR) was run by Dr Sandy Unger who was an interesting person and a colleague of Dr Timothy Leary. He was part of the Spring Grove Experiment to study the impact of LSD for use with persons with psychiatric disorders and to facilitate spiritual awakenings in patients experiencing Alcoholism. It was funded by the National Institute of Health. He was quite a character. He later married the office manager, and I performed the wedding song on my guitar at their wedding ceremony at his request.

During this period of my recovery, I met a number of people who had been around and in recovery since the 1940’s and early 1950’s, even people who knew and worked with Marty Mann. I saw Father Martin Chalk Talk on Alcoholism who immediately become my first Recovery Hero! I then started to run into him in my community and we became friends. He lived in a nearby town and I was honored when on one occasion in my first year of recovery he asked me to step in for him and help out with someone struggling with alcoholism when he needed to go out of town for a speaking engagement.

- Where you aware of Operation Understanding at the time it happened? What do you recall about efforts to normalize recovery in that era?

I don’t particularly recall it well. I was in early recovery at the time and just trying to figure out my own way. It was not until long after that I grew to appreciate the recovery movement and our rich history. At one point, a number of years later I moved up to Pennsylvania and worked at the Livengrin Foundation, which at the time was run by Mercedes McCambridge. Many people may now recall her from the clips of her brave testimony in front of Congress on recovery that Greg Williams and Jeff Reilly included in the Anonymous People as part of Operation Understanding. She let you know she was a star. According to Orson Wells, Mercedes was the greatest living radio actress, she has won an Academy Award for the movie All the Kings Men and was nominated for one for her work on Giant with James Dean.

Thanks to the Anonymous People, we are now much more aware of this period of our history. What people may not know is that she paid a price for her advocacy. Standing up and being open about being a woman in recovery led to her being blacklisted in Hollywood. She could not get work because she was open about her alcoholism. There were a lot of people in the recovery community who were opposed to living openly in recovery. There was a lot of controversy at the time about Dick Van Dyke being open about Alcoholism and the impact of public relapses on the perception of recovery. These early advocates paid a price for being open about addiction and recovery. We owe them a great deal for what they did for us.

- I have put some effort into interviewing people about the recovery summit in 2001. I don’t think you were there, but were you aware of it? When did you first start to see the influences of the new recovery advocacy movement in your community?

In the 1980’s-90’s I established a private outpatient addiction practice in Pennsylvania. During this era, we were seeing a lot of erosion of recovery efforts on a national scale. Lengths of stay in treatment centers were decreasing because of pressure from the insurance industry. There was such a focus on professionalism and documentation that the field became overburdened and set up barriers for our community to do the work of helping people get into recovery. We lost something in this era, the pendulum had swung away from recovery and the field became over-professionalized. Some treatment settings prohibited giving a client a hug or disallowed self-disclosure (talking about your own recovery). Brief therapy was all the rage, the notion that you could provide a handful of outpatient treatment sessions with a person, educated them about severe substance use disorder and recovery and they would be healed. The insurance industry loved it. The dots that connected treatment and recovery were severed. It was horrifying and something needed to be done to reconnect recovery with the treatment experience.

Some years later, my wife and I moved back to Maryland where I become the director of the Dorchester County Addictions Program. While there I became interested in developing community-based recovery support. I started to think about those old 12 step clubhouses, and I thought something similar could benefit my own community. With the support of State funding, I founded the Drydock Recovery & Wellness Center in Cambridge Maryland. I was heavily influenced by the work of Bill White and the concepts of recovery-oriented systems of care (ROSC) and recovery management. Soon thereafter, “The Anonymous People” movie was released, and it was a game changer! The movement became energized and focused on embracing many pathways to recovery. I am grateful to have seen and have been part of this positive emphasis on recovery and recovery community.

- How have views of addiction and recovery changed over the last four decades from your perspective?

Have people’s views changed? My short answer is yes and no. The work of Bill White, Greg Williams and so many others through the new recovery advocacy movement has definitely increased our capacity to talk about addiction and recovery openly. This has really increased public awareness of addiction and recovery. On the other hand, I’m sorry to say that I see a lot of disparaging, vile, hateful, ignorant, shaming, and judgmentally stigmatizing commentary concerning addiction and people suffering from and impacted by addiction on social media and other public platforms. It is heartbreaking to see how common are the misconceptions about who we are and what we experience. We have a long way to go to get to the point where society normalizes addiction and stops seeing it as a moral failing but instead something that is common, is treatable and from which recovery is the probable outcome given the proper care and community support in which people need to heal.

- You started International Recovery Day. Tell us about it and what it has accomplished.

I got the idea to start International Recovery Day (IRD) in the Fall of 2018. I was reading a bio on Marty Mann and all of her amazing advocacy pioneering work. I was simultaneously reading Bill White’s newly released Recovery Rising. In the back of my mind, I was also reflecting on Don Coyhis who was talking about the spider web of connection. I wanted to be part of reconnecting the dots and expanding recovery. I saw that we had through some of the new technology the ability to connect people in ways that was not possible before then. I started thinking about September being National Recovery Month which begins the day after we observe International Overdose Awareness. Many recovery-related events occur throughout the country (and now around the world) during this month. Holding International Recovery Day on the last day of the month (September 30th) would provide a month’s ending crescendo as an opportunity to be the day to honor and celebrate recovery worldwide and offer a beacon of hope to all impacted by addiction.

I started to imagine a scenario where everyone in the world who’d been impacted by addiction could launch their own virtual recovery rocket and anyone could watch them online streaming across the globe. I thought it would be an amazing way to express unity and focus the world on recovery in a non-politized way. Over time, I sheepishly realized that the imagery of all these rockets may actually look like the virtual start of WWIII! Given that awareness, we shifted the concept from Recovery Rockets to that of Recovery Fireworks – thus averting another worldwide disaster – whew! Today, anyone can register for free to launch their own virtual Recovery Firework on September 30th and watch it join with countless others around the globe rise up into the sky in celebration of recovery. https://internationalrecoveryday.org/

Purple is the color we embrace to symbolize the Recovery Movement. I was involved in a community near mine who was using the color purple to show support for recovery, they used that color because of that scene in the Anonymous People when Chris Herren of the Herren Project was talking to the kids wearing the purple shirts to support drug free living at a High School assembly. This was part of his work on Project Purple. My wife suggested that we focus on having people light things up in purple. That is what we did!

Even though International Recovery Day is only a few years old, it has already taken off! The web site is available in many different languages to increase accessibility. “Recovery Lights Around the World” on September 30th invites everyone to get out and light up your back porch, your City Hall, and/or your State Capitol building. So far, we’ve had countless buildings, bridges, and structures light-up in purple on the 30th to include such iconic places as Niagara Falls, the Rock and Roll Hall of fame and Aloha Towers in Hawaii. Last year, over one fourth of all countries on the face of the earth participated in International Recovery Day. We are just getting started, our goal is to get every single nation of the world to participate. What a show of unity, diversity, and a testament to many pathways of recovery. I think we really can turn the world purple one day at a time!

- When we were at the CCAR Many Pathways to Recovery conference, you announced that Faces & Voices was going to carry International Recovery Day forward / What are your hopes for this change and what it signifies moving forward?

For the past few years, I’ve been thinking about how best to insure the future of International Recovery Day. I am getting older and it is important to me. I started talking to Bill White and a few other people about the idea of making sure it had a home long term that could increase its visibility and really expand it in the way to connect the world and show the power of recovery to heal. Through the process of reflection, meditation, and consultation it appeared that Faces & Voices of Recovery was the ideal place for it to go, given that they have the technical, staffing, financial, and networking resources to move I.R.D. forward in a major fashion. I soon discovered that Faces & Voices’ C.E.O., Patty McCarthy was thinking along the same lines. She invited me into conversation to discuss the possibilities, and the rest is history.

So, at the CCAR Multiple Pathways of Recovery Conference we made a formal announcement that Faces & Voices of Recovery was going to add it to its projects. Yes Bill, as you have joked with me about retiring, I am retiring in that I will be involved in IRD as an advisor, sort of semi-retired. I am very excited to see what it will evolve into and suspect that it may really help create a sense of world unity and connection in the global recovery community.

- You have been a major contributor to the recovery movement over your lifetime. What would you want young people to know about what you have learned along the way? What are your hopes for the next generation?

I have been thinking about this question since you first asked me to do this interview. I thought about my early years of doing the work and who I wanted to be like. As I have shared, I was blessed to have had some great mentors and role models. I felt a little overwhelmed and was trying to emulate all of these amazing people and also find my own voice. Early on in my career I had a colleague I looked up to by the name of Joe Massie. He was such a gifted counselor. They actually named an adolescent unit after him in Western Maryland. Joe was so well respected. He was very limited in his formal education, but he was a genius and a gifted communicator. I asked him about how I could honor all of the work of all of these people in my own efforts moving forward. He gave me the sage advice to just be myself. I have followed this advice even as I worked to understand, honor and preserve the work of my recovery heroes!

One of the things I reflect on when I think of where we are now is that the whole movement has gotten a lot more complex. There arises a chorus of voices- from prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery. It is my sense that not all of these groups fully understand what addiction is and the consequences of having a severe substance use issue. I think it is very important moving forward that anyone committed to doing this sacred work develop a deep understanding that moderation does not work for everyone and that there are those of us for whom recovery is a matter of life and death.

The things I would hope that the next generation reflect on are rather simple. Concepts that have served me and a lot of people in recovery quite well:

- Be yourself

- Take care of yourself

- Be humble

- Do no harm

- Do the next right thing

- Always take the high road and do the ethically proper thing.

- Put principles before personalities

- Be open minded

I did not invent these concepts. They were around a long time before I learned them. When I reflect on my recovery heroes and think about what they accomplished and how they did it, I see these same concepts as the things that they centered on in their own lives and in their own work. That is my wish for the next generation. I know that if they do these things, dream big and keep focused on them, they will accomplish so very much!

Paul Tieger is the Founder and CEO of Speed Reading People, LLC. He is also a principal of IConnect Health, an international expert on personality psychology, and the author of five bestselling books. Paul currently is the lead researcher for the SMART De-Stress RX Study, which seeks to determine the connection between personality type and addiction issues.

In this podcast, Paul talks about:

- His extensive background in personality psychology and trying to understand who people are

- His most famous case from when he was a jury consultant

- The new SMART study’s purpose is to determine genetic predisposition to addiction issues based on personality type and how SMART can tailor its approach to different people

- Why personality type trumps all other factors like age and gender

- How to prevent confirmation bias

- Dr. Tom Horvath’s enthusiasm for this groundbreaking study

- The three parts of the study the participants will take

- Developing the De-Stress RX personality test as an individualized approach to reducing stress based on the 16 personality types

- The value in receiving personal RX results

- How the COVID era stress has influenced personality types

- How SMART will be communicating how people can participate in the study in the coming weeks

- How to register for the webinar on Wednesday, March 2nd

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

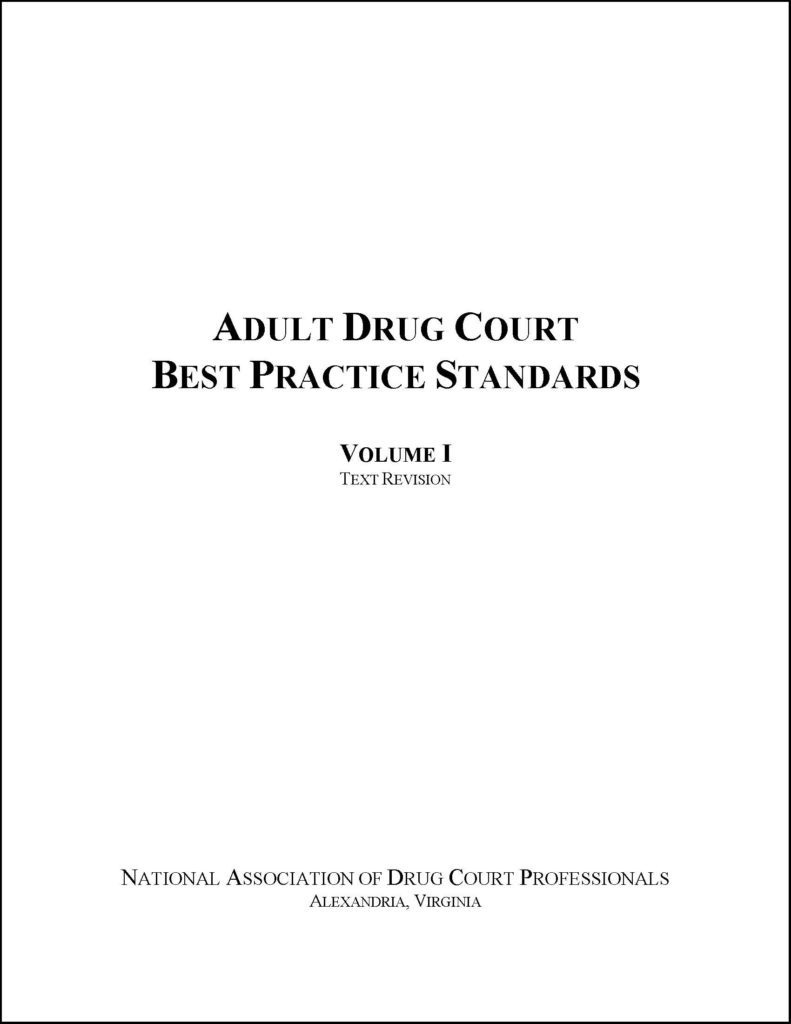

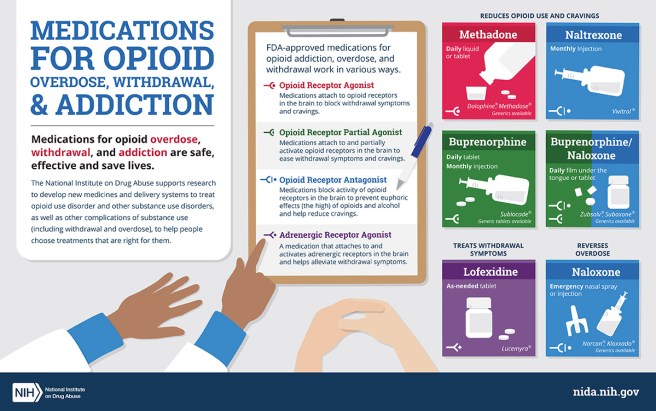

ACCESS NADCP’s FREE SUITE OF MAT RESOURCES

As treatment courts are on the front lines of the opioid crisis, NADCP is here to serve you. NADCP, together with partners in the addiction medicine field, is leading efforts to provide resources to treatment court practitioners for implementing a safe and effective treatment program that includes medication for addiction treatment (MAT) in their court. These resources are completely free to access, download, and use. Best of all, we have the nation’s leading experts in our office and as our partners to help you.

Best Practice Standards

NADCP’s Adult Drug Court Best Practice Standards are the blueprint on which successful adult drug courts are built. Rooted in more than 25 years of empirical study of addiction, pharmacology, behavioral health, and criminal justice, the standards address the most critical aspects of adult drug court and provide an evidence-based guide for how programs should operate to ensure success in treating individuals with opioid use disorder. They stipulate that treatment courts do what is within their ability to make accessible all FDA-approved medications to treat addiction, as determined in consultation with the patient by a treating physician with expertise in addiction medicine.

Online MAT Training Via NADCP’s E-Learning Center

Developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry, this online training educates treatment court professionals on MAT for substance use disorders with a primary focus on opioid use disorders.

MOUD Toolkit

Developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry, this online training educates NADCP’s Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) Toolkit for Treatment Courts provides practical resources for programs to implement systems to offer MOUD to their participants in a safe, legal, and scientifically sound manner. Download and read the toolkit, then download the appendices and adapt them for use in your treatment court program.

Online Naloxone Training

Developed in partnership with the Center for Opioid Safety Education at the University of Washington, this online training educates treatment court professionals, participants, families, and other stakeholders on the safe use of the overdose reversal medication naloxone. It will teach you how to spot the signs and risks of an overdose, what naloxone is and how it works to reverse an overdose, obtain the medication, train treatment court participants in its use, and more.

Naloxone Fact Sheet

Developed in partnership with the Center for Opioid Safety Education at the University of Washington, this Download our free practitioner fact sheet “Naloxone: Overview and Considerations for Drug Court Programs” to learn more about the overdose reversal medicine.

MAT Pocket Guides

Developed in partnership with the American Society of Addiction Medicine, these handy pocket guides are for treatment court clinicians, team members, and participants.

CLINICIANS

The pocket guide for clinicians is designed to help counselors and therapists working with participants refer and link participants to opioid treatment services in outpatient offices, clinics, and Opioid Treatment Programs.

TEAM MEMBERS

Developed in partnership with the Center for Opioid Safety Education at the University of Washington, this Download our free practitioner fact sheet “NaloxoThe pocket guide for team members is intended for non-clinicians (e.g., judges, coordinators, attorneys, probation, case managers, peer mentors, recovery coaches, law enforcement) and describes how team members can support both the provider and those participants prescribed or considering MAT.

PARTICIPANTS

The pocket guide for participants is designed to educate clients who may be prescribed or considering MAT, as well as their families and support systems, including peer mentors, recovery coaches, and peer recovery specialists.

The post Free MAT Resources appeared first on NADCP.org.

There is and can be no ultimate solution for us to discover, but instead a permanent need for balancing contradictory claims, for careful trade-offs between conflicting values, toleration of difference, consideration of the specific factors at play when a choice is needed, not reliance on an abstract blueprint claimed to be applicable everywhere, always, to all people.

A recent Health Affairs article by Nora Volkow about non-abstinence endpoints for addiction treatments has received a lot of attention. Some are hailing it as a long-overdue change of course and others have expressed concern that it represents a step in the direction of abandoning recovery.

Personally, I don’t see this as an especially noteworthy event for a few reasons:

- As linked to in the article, Nora Volkow has called for alternative endpoints nearly 4 years and has advocated for broader use of medication to treat substance use disorders (SUDs) on the basis of non-abstinence outcomes for more than a decade.

- The FDA issued guidance with non-abstinence endpoints years ago.

- The idea that complete abstinence is the metric for medically-assisted treatment (MAT) effectiveness is just not true. I reviewed some of the most frequently cited evidence for MAT and most studies don’t even report information on abstinence.

Different in kind or severity?

The article commits one of my pet peeves by using both “addiction” and “use disorder” interchangeably, without distinguishing between the different kinds and severities of substance problems. This is always important but it seems particularly important when discussing treatment endpoints.

I’ve written at length about how important I believe it is to recognize different kinds of substance problems rather than just different severities and the implications of the DSM 5’s shift from a categorical model of alcohol problems to a continuum model. In short, I believe addiction (the most severe and chronic form) is not just a more severe version of other alcohol and other drug problems, I believe it’s a different category of problem.

However, DSM 5 put all substance problems were put on a single continuum, meaning low severity problems share the same diagnosis as high severity, high chronicity alcohol problems. I see this as akin to rolling all respiratory diseases into “respiratory disorder” as a diagnostic category. The different kinds and categories of respiratory diagnoses have profound implications for determining the prognosis and treatment plan.

For example, for high severity, high chronicity problems (addiction), abstinence has long been considered the most appropriate treatment goal, while moderation has been considered an appropriate goal for low to moderate severity problems. (See here, here, and here for examples.)

Non-abstinence endpoints?

As stated above, non-abstinence outcomes have long been widely accepted as reasons to adopt and expand the use of medications. In fact, those outcomes have become the basis for big federally and foundation funded projects, like expanding low-threshold buprenorphine prescribing in emergency departments.

So… where’s the controversy?

I’m not up on the details of the FDA approval process, but if there have been barriers to getting treatments approved to achieve these endpoints, clearing those barriers is a good thing, particularly in the context of the OD crisis.

First of all, non-abstinence endpoints will align well with the desired treatment outcomes and full functioning for most people with alcohol and other drug problems.

For others, for whom abstinence is necessary for sustained recovery, non-abstinence endpoints may: 1) be useful in the process of determining whether abstinence is necessary for sustained recovery; 2) represent an incremental step toward abstinence; 3) accomplish harm reduction goals; 4) represent one element of a much more comprehensive treatment plan; 5) represent deference to patient preferences.

The OD crisis has increased the stakes, making it clear that we can’t allow the best (for some) to be the enemy of the good. I suppose it’s also possible that an open embrace of these endpoints could result in better informed consent. Some of the tension around non-abstinence endpoints can be attributed to one-wayers who think everyone needs and should only be offered treatments focused on immediate abstinence. However, much more often, I think the tension is related a misalignment between the desired outcomes for patients and families dealing with the high severity/chronicity type, the demonstrated outcomes for the treatment, and the way that information is presented to patients and families.

Looking ahead

So… if non-abstinence endpoints are already well established in research and practice, we’re all set, right? Not quite.

Despite the establishment of these endpoints, there has been some resistance and ambivalence, which I think can be attributed to two factors.

The first is whether they lower expectations for full, sustained recovery. Here, Eric Strain questions whether the field has been ambitious enough on behalf of our patients.

This focus on opioid overdose deaths is overlooking the importance of doing more to help people than preventing a death. Not overdosing is an insufficient endpoint for treatment or for societal and medical interventions – it’s a starting point. We fool ourselves and do a disservice to patients if we allow this to be the measure that allows us to declare success. If a patient with a significant leg wound has the bleeding stopped with a compress, the medical field does not declare victory. Providers clean the wound, stitch it, arrange for physical therapy for the leg, and work to maximize the functioning of the person.

He goes on to call for flourishing as the goal for patients with alcohol and other drug problems.

We should fight to ensure our patients and this field does not accept anything less than flourishing – that should be the goal we bring to our work in research and clinical practice.

One of the major challenges we face is understanding and agreeing upon what’s required to achieve flourishing.

For people with low to moderate severity, eliminating binges or reducing heavy drinking days may be all that is required to make flourishing possible.

For others, like most with addiction, reduced use of opioids will not deliver the improvements in quality of life that they and their loved ones want. Bill White addresses why recovery from addiction can’t be achieved through subtraction of symptoms.

Recovery from opioid addiction is also more than remission, with remission defined as the sustained cessation or deceleration of opioid and other drug use/problems to a subclinical level—no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for opioid dependence or another substance use disorder. Remission is about the subtraction of pathology; recovery is ultimately about the achievement of global (physical, emotional, relational, spiritual) health, social functioning, and quality of life in the community.

Further, for most with addiction, their problem is not multiple distinct substance use disorders like, opioid use disorder, stimulant use disorder, and alcohol use disorder. Their problem is addiction. Treatments targeting individual use disorders too often miss the nature of the problem and set the stage for outcomes where the surgery might be deemed a success but the patient dies.

This brings us to the second factor, distinguishing between patients for whom abstinence is necessary for full, sustained recovery, and those who can achieve flourishing without abstinence.

Dirk Hanson describes how dynamics in the current drug policy and addiction space have made the differences between these types of alcohol and other drug problems fuzzier rather than clearer.

For harm reductionists, addiction is sometimes viewed as a learning disorder. This semantic construction seems to hold out the possibility of learning to drink or use drugs moderately after using them addictively. The fact that some non-alcoholics drink too much and ought to cut back, just as some recreational drug users need to ease up, is certainly a public health issue—but one that is distinct in almost every way from the issue of biochemical addiction. By concentrating on the fuzziest part of the spectrum, where problem drinking merges into alcoholism, we’ve introduced fuzzy thinking with regard to at least some of the existing addiction research base. And that doesn’t help anybody find common ground.

So… as I’ve said above and elsewhere, I think we’d do ourselves a big favor by returning to thinking about alcohol and other drug problems in terms of categories rather than a spectrum. Academics and researchers could do a valuable public service by not using abuse, dependence, SUD, and addiction interchangeably and explaining to readers what type of alcohol and other drug problem they are researching, treating, and discussing.

Why does anyone care about abstinence?

This brings me to another thought about how to move forward.

The spectrum approach has not only introduced fuzziness into understanding the types of alcohol and other drug problems, it’s also introduced fuzziness into our understanding of recovery.

I’m not aware of any historical movement of people with low to moderate severity alcohol and other drug problems identifying themselves as “in recovery”, but academics and advocates have expanded the category to anyone who identifies as once having had a substance problem and no longer does. This, of course, added millions who, for example, engaged in excessive use as a young adult and moderated or quit on their own. This didn’t just add numbers of people to the category of recovery, but changed how recovery had historically been understood.

Recovery had historically been limited to those with the most severe alcohol and other drug problems (addiction) characterized by impaired control over the quantity used, amount of time spent using, and/or whether or not they used. These people had tried moderation and/or eliminating some substances but not others. However, their addiction and it’s hallmark of impaired control made abstinence the only path to full sustained recovery.

This is not a moral decision, it’s a practical decision based on extensive experience and suffering.

This brings me to why I think Volkow’s article got so much attention.

Healthcare and society must move beyond this dichotomous, moralistic view of drug use and abstinence and the judgmental attitudes and practices that go with it.

“Making Addiction Treatment More Realistic And Pragmatic“,

Health Affairs Forefront, January 3, 2022.

The linking of abstinence to moralistic and judgmental attitudes and practices plays into culture war battles that consume too much energy and attention within the field. I don’t think this was her intention, but I think many read it as invalidating of abstinence as an important endpoint and understanding relapse as, not just a disappointing setback, but a serious safety event without any guarantee of restabilization.

I believe the fuzziness around the conceptual boundaries of recovery intensifies conflict around these issues. There was a time when I welcomed researchers and academics focusing recovery. My friend Brian Coon has argued that “recovery” ought to be left to mutual aid groups and proposed that professionals focus on “stages of healing.” I’ve been coming around to the notion that we might be better off focusing on quality of life.

Closing

I fear this has been a meandering and repetitive post, so I’ll summarize here:

- It’s important to recognize and distinguish between the types of alcohol and other drug problems in research, treatment, and professional communication.

- It’s important to recognize that some endpoints (abstinence) aren’t necessary for some SUDs (mild to moderate), AND some endpoints (non-abstinent) will not be compatible with high quality of life for many with high severity SUDs (addiction).

- Further, we can affirm that it is not moralistic to recognize that, for a minority, abstinence is the only endpoint that will allow maximal functioning. (We can also acknowledge that this isn’t grounds for coercion.)

- We might do better to focus on quality of life, flourishing, stages of healing, etc. than on recovery, due to its increasingly fuzzy conceptual boundaries.

- Non-abstinent endpoints can serve multiple purposes that don’t have to, and shouldn’t, replace abstinence as the optimal endpoint for a minority of people with alcohol and other drug problems.

Mindfulness, as described by Jon Kabat-Zinn, means to pay attention in the present moment, on purpose, and without judgement. That’s it.

What this means is that mindfulness is a broad category that includes all kinds of practices that can help you be more present. It is more than meditation, although meditation is a kind of mindfulness. You do not have to limit your practice to meditation, you have lots to choose from and it is uniquely your own. The practice that works best for you might not resonate with your coworker, so experiment. There are tons of apps and YouTube videos that you can explore to help you practice mindfulness.

Here are some suggestions to get you started:

- Focus on your breath.

When you do this practice, don’t try to change your breath pattern—just notice. Be curious about the way you breathe.

- Sit quietly and observe your thoughts.

Practice not attaching to them. Just notice what is coming up for you. If you notice that your mind has wondered and that you are entertaining a thought, return to focus on your breath for a minute or two.

- Eat in a mindful way.

Pick something you particularly love to eat. Pay attention to all of your senses as you eat. What does it smell, feel, look, sound, and taste like when you eat? Do this slowly and really savor each bite.

- Take a walk-mindfully.

Notice all the sights around you. What do you hear and smell? How does the air feel on your skin? Notice your foot touching down and the rate of your gait.

- Listen to your favorite song.

Pick a word of phrase that is repeated several times in the song. As you listen, count the number of times you hear that word or phrase sung.

The latest meditation research shows that while new practitioners can experience changes in their brains that are positive, the real change comes from consistent and longer practice. That’s when you will start to see permanent, and positive changes in the brain, like improved concentration and better emotion regulation.

Your practice can be as long or as short as you want it to be. If you only have five minutes, great, use it!! Most mindfulness experts say that 20 minutes a day is a good amount to shoot for, but make that your long-term goal, and start with realistic amounts of time. In fact, starting with a short practice is a good idea because you will have some early success and will be more likely to continue. Either way, find something you can do regularly and you will start to see the benefits.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.