Lately I’ve been working out a practical structure1 for a 5-year model of clinical involvement for patients with addiction illness (not less severe presentations).

What I have in mind is quite concrete but would take a lot of words to say. I am often a visual or spatial thinker, and for this topic it’s true once again.

Suffice it to say the image below shows the starting point of formal clinical engagement (which could be an outpatient or residential program) on the far left, and a five-year path moving forward in time. The example shown is one individual person: the red dots are different problem indicators, and the green dots are different wellness indicators.2

Over the five years, as this example shows, the problem indicators are dropping, and the wellness indicators are rising.3

You’ll notice that even at the very start there are wellness indicators present (specific strengths, assets, resiliencies and so forth). And you’ll notice that out at five years there are also some problem indicators that are still present.4

I showed this to a colleague last week and was asked a couple of questions that helped me see some of my assumptions and blind spots.

One question they asked was, “Why do you have that short wall on the left side?”

I liked that question because it rattled me awake.

- My immediate answer was that it shows the time of admission to a formal primary addiction treatment service (like a residential program or an Intensive Outpatient Program).

- But I loved that question because it basically invokes the idea of the “Engagement/Persuasion” and “Stabilization” phases that I did not show5 and that come before the beginning of the “Active Treatment” phase.

The other question they asked was why I had the long wall there – like, “Why do you show any walls at all, instead of showing just the indicators?”

- The bottom line is that the shape of the two walls (without any other sides) is meant to carry the idea of a system that is both structured in some ways and open in other ways. My classic example of this is how no appointments are needed for some quick oil change shops, but for other work an appointment is made.

In the days ahead I’ll be working out and adding pre-planned service intervals, problem and wellness targets, and continuous personal processes.

And I’ll also be adding some clinical, coaching, and peer support methods to help fill out the function of the model – based on both the pre-planned intervals and the individualized presence/absence of the various indicators.

4https://recoveryreview.blog/2021/04/12/recovery-orphans/

5https://recoveryreview.blog/2020/02/01/peer-support-or-harm-reduction-or-recovery-coaching/

It is great to see this piece coauthored with Ryan Hampton Author of Unsettled published in STAT news

RCOs deserve better than bake sales

Funding for recovery community organizations is a patchwork affair. There has never been an established, stable funding mechanism to support them. Some are funded through time-limited grants, some through block grants to the states, and others rely on grassroots funding drives.

Recovery community organizations are the first groups to help individuals struggling with addiction, but the last to receive funding that translates into healthier communities. They are a huge part of the solution, but can accomplish only so much with self-funding.

Until these organizations are treated with the same respect as other mental health resources, and funded in proportion to their results, overdose deaths will continue to rise. Their reach will remain limited, as will their ability to hire peer workers with lived experience to help people sustain their recovery and enrich their communities.”

Link to Full Article in STAT NEWS

Guest blog by SMART Facilitator Ted Perkins

A new study, conducted in partnership with the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health, confirmed a troubling addiction trend among African Americans. Based on overdose data and death certificates from four states, it found that the rate of opioid deaths among Black people increased by 38% from 2018 to 2019, while rates for other racial and ethnic groups did not.

The recent highly-publicized overdose-related death of African American actor Michael K. Williams was a grim reminder of how drugs and alcohol can strike down even the most successful Black artists and entertainers in the prime of their life. This is not just a loss of life, but a loss to our culture and society. As we all know, addiction is not just a private concern; it robs all of us of our friends, family members, and beloved icons as well.

For Black History Month, SMART Recovery would like to honor and remember those African American artists and entertainers we’ve lost to addiction over the years in the hopes that their struggles can inspire anyone to seek out the help they need to overcome their own addictions.

BILLIE HOLIDAY – 1915 – 1959

“Lady Day” as she was lovingly called, was an iconic jazz and swing music singer with a voice as vibrant and unique as her personality. She got her start grabbing quick singing gigs in Harlem nightclubs in the 30s, and by the age of 20 had landed her first recording contract. She achieved widespread popularity and success in the two decades that followed. Sadly, Lady Day suffered from a heroin addiction possibly exacerbated by mounting legal and financial troubles. She served prison time, and was under arrest in her hospital bed when she passed away from cirrhosis of the liver in 1959. A film was made last year about her life called The United States vs. Billie Holiday available to stream on Hulu.

PRINCE – 1958 – 2016

Prince’s talents knew few bounds. A true polymath, he was able to play every instrument and record his own music. He had dozens of #1 hits, sold over 150 million records, directed and starred in films, created his own videos, and wrote and produced hit songs for Sinéad O’Connor, Chaka Khan and Sheena Easton. Prince was famous for his over-the-top stage performances, but unfortunately over time they caused physical injuries that required pain medications. Sadly, he died from a Fentanyly overdose in an effort to address his pain. Prince never stopped recording, and may have written well over 1,000 songs in his all-too-brief lifetime. There is no telling how many more top-ten hits, films and concert performances were cut short by his opioid addiction.

MICHAEL K. WILLIAMS 1966 – 2021

There are few better examples of an individual using grit, determination, and talent to rise to the heights of film and television fame and critical recognition. Raised in the projects in Brooklyn, he enrolled in theater classes to stay out of trouble. Poverty and intermittent homelessness never slowed him down, and after careers as a backup dancer and model, Williams scored his big break by landing the role of Omar Little in HBO’s The Wire. He went on to star on Netflix’s acclaimed series Boardwalk Empire and was also nominated for a Primetime Emmy for his work on the HBO Biopic Bessie. He transitioned easily to films and had supporting roles in Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave and Gone Baby Gone. Sadly, his is another promising career cut short by Fentanyl.

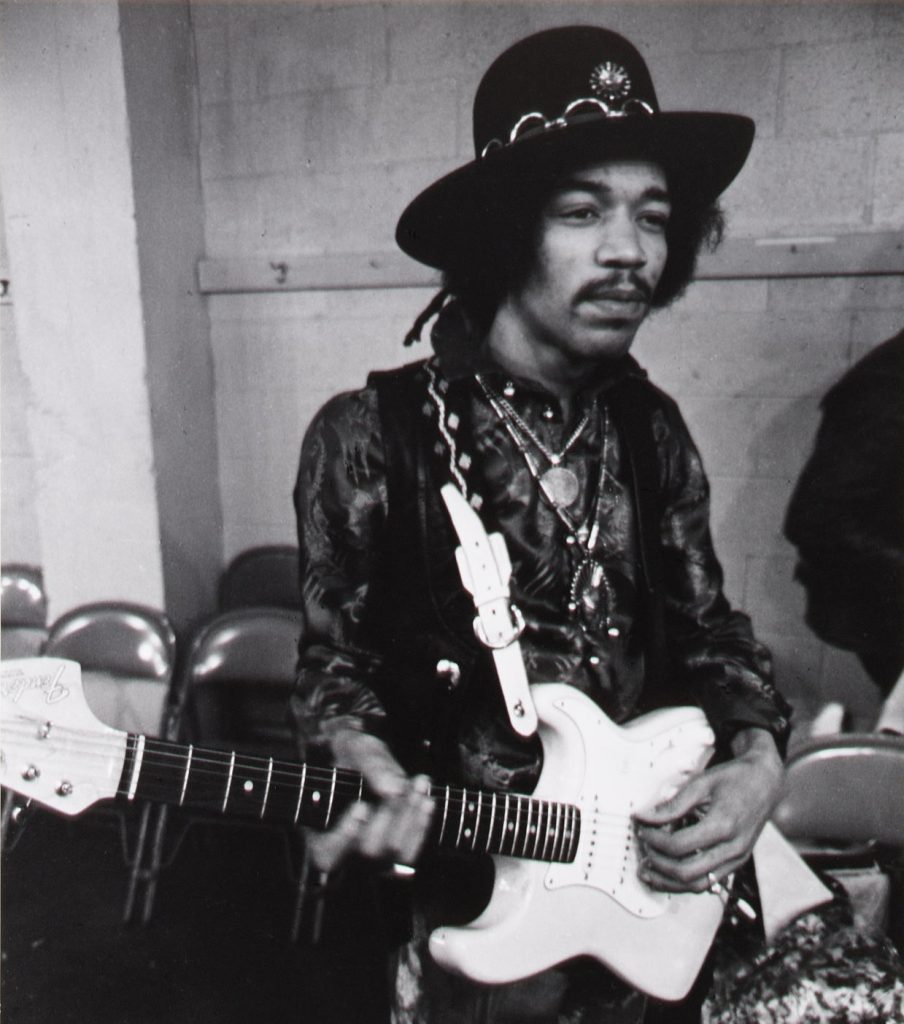

JIMI HENDRIX 1942 – 1970

Hendrix changed rock and roll forever and inspired countless rock guitarists from Jimmy Page to Prince to Eddie Van Halen. While his iconic concert performances and commercial recording success are well known, Hendrix was also a pioneer in the field of audio engineering and recording. He popularized sound effects few of us ever knew existed, like fuzz distortion, Octavia, wah-wah, and Uni-Vibe. While most other musicians turned down their amplifiers to eliminate gain, Hendrix used it to create rock music masterpieces. Hendrix’s life was cut short at the tender age of 27 due to barbiturates. Had he survived, there’s no telling how many more amazing songs and performances he would have given the world.

WHITNEY HOUSTON 1963 – 2012

Houston’s battle with addiction was widely reported in the years before her premature death in 2012 due to atherosclerotic heart disease exacerbated by cocaine use. Only 58 at the time of her death, she had already sold over 200 million records and recorded countless #1 hits. Dubbed “The Voice”, Houston also starred in blockbuster films including The Bodyguard, whose title song I Will Always Love You became the bestselling song by a female artist of all time. We could not possibly do justice to Houston’s amazing career and contributions to music and entertainment here, except to say that she is sorely missed.

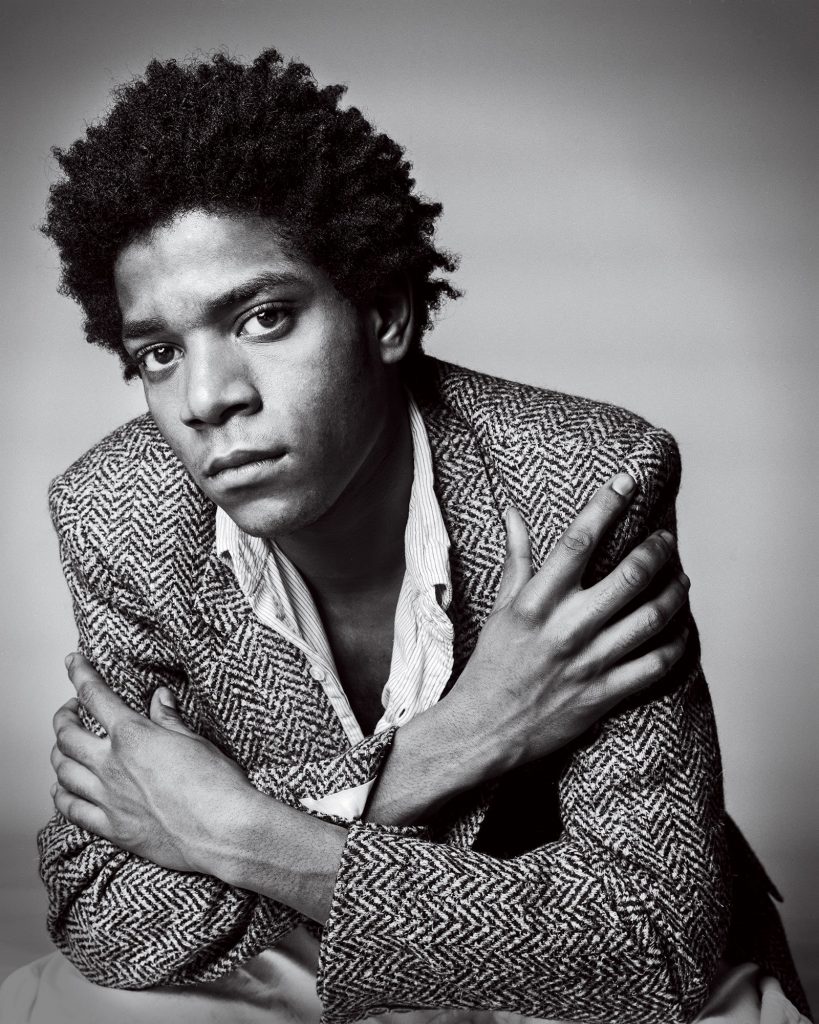

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT 1960 – 1988

A fresh, vibrant and transformative vision in the art world, Basquiat brought graffiti into the mainstream in the 70s, and helped pave the way for the rise of hip hop in the 80s and 90s. His paintings didn’t only show things, they said things about income inequality, segregation, even mindfulness. He was barely into his 20s when his works were on display in major museums around the world. Sudden fame and the death of his close friend Andy Warhol are cited as reasons for why he may have turned to heroin. Although he tried methadone treatments to achieve sobriety, he lost his life to a heroin overdose at 27.

FUQUAN JOHNSON 1979 – 2020

A rising star in the comedy world, Johnson perished along with two other entertainers at the hands of a fentanyl-laced cocaine overdose at a Los Angeles party just a few months ago. Fellow comedians were quick to eulogize Johnson and pay tributes to an entertainer who had a blazing career ahead of him.

Sadly, there are many more Black artists and entertainers whose lives, careers, and positive contributions to the arts and humanities were cut short due to addiction. We’re all familiar with the tragic losses of Michael Jackson, but let’s not forget Franki Lymon, David Ruffin of The Temptations, Donnie Hathaway, and many, many more.

Celebrity or not, any death due to addiction is an avoidable tragedy, and SMART Recovery continues to work every day to motivate and inspire anyone who needs help to recover.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Recently here on Recovery Review Jason Schwartz has been posting some fairly interesting new material, as well as re-posting older material, about the idea of addiction as a disease.

The material he has shared has grown interesting enough and produced enough thoughtful conversation on various platforms, that I wanted to share a version of my very first post on Recovery Review (from 10/21/2019). It pertains to the topic. Over the next few days I might post one or two more that are relevant to this topic Jason has highlighted.

Earlier today, Bill Stauffer posted important and interesting content about the elimination of the classic diagnostic categories separating problematic use and addiction, their replacement with a simple list of criteria, and the relative uncertainties associated with the meaning (if any) concerning the number of criteria for SUD that may be met. That post can be found here.

That post reminded me of conversations I have had over the years with Norman Hoffmann concerning what Norm calls “The Big 5”.

“The Big 5”

Norm has both published, and presented at national conferences, his work concerning what he calls “The Big 5” substance use disorder (SUD) criteria from the DSM-5.

In short, Norm has examined the relative weight of each of the 11 DSM-5 SUD criteria, separately, as applied to the probability of having any one or more additional positive criteria for SUD (from data collected on thousands of consecutively incarcerated individuals).

The empirical questions and answers on The Big 5 as Norm has presented them are summarized here:

- Question: Which of the 11 DSM criteria for SUD are commonly found among individuals with no SUD diagnosis?

- Answer: Tolerance, and Use in dangerous situations.

- That is to say, in his sample, the presence of tolerance as a single factor did not make it more likely than not that any additional criteria were present – and the same was true of use in dangerous situations as a single factor.

- Question: Which of the 11 DSM criteria for SUD are commonly found among those with mild to moderate SUD?

- Answer: Unplanned use, Time spent, Interpersonal conflicts, and Use in spite of medical/psychological conditions.

- Question: Which DSM criteria for SUD are found primarily in severe SUD’s?

- Answer: Efforts to control/cut down but unable (rule setting), Craving with compulsion to use, Failure to fulfill role obligations, Activities given up or reduced, Withdrawal.

- That is to say, in his sample, the presence of any one of these 5 criteria, separately, was more likely than not to be present among 6 or more total positive SUD criteria for any one individual.

In presenting these results from his research, Norm has asked if perhaps the total constellation of The Big 5 is what is commonly called the disease of addiction. Interestingly, Norm has also noted the individual may fit mild or severe characteristics (aside from DSM scaling), based on The Big 5, and as a result he has expressed the following questions:

- Are those with mild to moderate DSM ratings without any of the Big 5 able to moderate use with less intense and briefer services?

- What are the implications of The Big 5 for etiology and course of illness of the individual?

- Specifically, do those that are positive on 2 or more of Big 5 in fact require initial residential placement and/or more intense and longer care, and require abstinence – even when not numerically “Severe” according to DSM-5?

Overall, Norm encourages the clinician to consider the pattern of positive criteria, in addition to the mere total number of criteria present.

Guest blog by Kareem Starkes – J #56138

My name is Kareem Starkes, I am 47 years old and have been incarcerated in California since 1998. My sentence is 60 years to life. This sentence is a result of California’s “Three Strikes and You’re Out” law.

I have a prior felony conviction history consisting of one prior juvenile adjudication at age 17 and one prior adult felony conviction at age 20. The present conviction is my second adult conviction. The juvenile adjudication counted as a strike, resulting in my being sentenced per the three-strikes law.

From 1998 until 2009, the atmosphere in California’s prisons was extremely violent. This violent prison culture was fostered by both the inmate population as well as correctional staff. California’s prison system was then the California Department of Corrections (CDC) without the “Rehabilitation,” which was added after the federal government intervened. It became the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) because the federal government cited CDCR’s overcrowding as constituting cruel and unusual punishment for its inmate population. As a result, rehabilitation programming began to become more prevalent within CDCR’s institutions.

Personally, I have been in the “precontemplation stage” of change from the very beginning of this present term of incarceration. Conditions within the state prisons where I was incarcerated were such that violence was a day-to-day reality, and it was extremely difficult to consider anything aside from daily survival and prevention of being assaulted and/or killed. I chose a mentality of “go along to get along” as a means of my own survival. It was a choice that I made and lived out for almost 17 years of this term until both time and circumstances brought me to a place where I could no longer deny the necessity of my having to change.

My process of positive growth and transformation began in 2012 at the age of 36. It was then that I began to seek help and to do so by availing myself of the rehabilitative programming being offered within the institutional settings. Through rehabilitative programming, coupled with seeking to strengthen my spiritual principles and values and relationship with God, I began the process of self-exploration and assessment.

I began to embark upon the journey of deeply reflecting upon my life, in order to identify the points and times where I found myself in desperate emotional states which had negatively influenced my thought process and perspective. I began to identify why I chose to ultimately adopt self-destructive thinking that led to many of the poor choices and decisions that I have made. These resulted in being engaged in criminality and criminal acts that have been harmful to innocent persons, communities, and to myself.

Rehabilitative programming has been my catalyst for the process of positive growth, change, and the transformation I am blessed to have undergone. It continues to be a lengthy process and journey, nevertheless it is a noble and good endeavor that I feel privileged to be experiencing. I am constantly seeking to be engaged with any form of rehabilitative program and/or organization that may provide the knowledge, tools, and life skills necessary for me to be living a responsible and productive life, one that is rooted in my making living amends for all the wrong and harm I have caused others.

I have reached the place in my life where my daily focus has become being in service to others while paying forward the care, support, consideration, and love that so many good people have invested in me throughout my journey of change.

As I continue to endeavor rehabilitative programming, I learned of new and different programs that are available. I came to learn of the SMART Recovery program as a result of a rehabilitative course I engaged in called “Hustle 2.0”. In this course a listing of addiction recovery programs was given, including SMART Recovery. I had never heard of SMART Recovery before seeing it listed in that book. I asked my wife to go online and find information about SMART Recovery. After some investigation my wife was able to send an email to SMART’s headquarters in Mentor, Ohio and they began to communicate with me.

From there I received all the information needed to begin a SMART Recovery meeting. I absolutely love the SMART Recovery program and all of its Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) tools. The CDCR has only one CBT program called Cognitive Behavioral Intervention (CBI), which consists of two in-person group meetings. This CBI programming being offered through CDCR is a very good program, however, it is extremely difficult for interested persons to be placed into the program.

The great thing about the SMART Recovery program is that it is a CBT based program consisting of similar CBT based tools to CBI. The difference between the two is that unlike the CBI program, the SMART Recovery program is designed in such a way that no licensed clinician is needed to facilitate the program. Also, the program structure is such that any interested person desiring to begin a SMART Recovery meeting group may do so by simply following the SMART Recovery format and getting it going.

In this way, more of the population within our institutional community may be given the opportunity to be exposed to and avail themselves of the CBT tools and life skills necessary to bring about positive change. This happens without having to be placed on any waiting list and having their journey and process of recovery put on hold due to administrative determinants and constraints.

I am thankful for having received the support of the SMART Recovery staff I am in contact with. I presently facilitate two voluntary men’s support groups that I have created here at my facility. I am currently in the process of starting an InsideOut: A SMART Recovery Correctional Program® meeting group here at my facility. The InsideOut program is designed for incarcerated individuals. The men here will greatly benefit from the InsideOut program as I already have. Support for the InsideOut group beginning has been phenomenal with our community here, so I’m excited about the journey ahead of beginning SMART Recovery InsideOut here at Ironwood State Prison.

It is said that where one door closes, another is opened. SMART Recovery should be in all of CDCR’s institutions, and I am committed to doing my part in making this a reality. As CDCR has become committed to rehabilitative programming, there is absolutely no reason why SMART Recovery meetings and InsideOut are not at the top of CDCR’s rehabilitative programming list! Let’s Go SMART Recovery!

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

“Let us use whatever power and influence we have, working

with whatever resources are already available, mobilizing the

people who are with us to work for what they care about.” – Margaret Wheatley

The title of this post comes is inspired by Margaret J. Wheatley, Who Do We Choose To Be?: Facing Reality, Claiming Leadership, Restoring Sanity (2017). The book came up in a recent conversations I had with Phil Valentine of CCAR when we were talking about influential readings. He told me about it and suggested to me it was to be digested slowly. I am an avid reader and sat down to read it from cover to cover. The truth of his words became clear to me after a few pages. Wheatley talks about how all things – even societies, have life cycles and that ours was in a period where large scale change is not often viable. Our institutions have decayed in the current stage of our society that they are largely ineffective at broad systemic change.

She suggests focusing locally and developing leaders to create space to support healthy community. I confess to not yet having finished her book. Having read books like Putnam’s Bowling Alone, The Fourth Turning by Strauss and Howe and Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed by Jared Diamond the topic is not new, but her focus (as far as I can see from about one halfway in) is to encourage leaders to develop and support community in ways that nurture people through difficult times. She calls these spaces “Islands of Sanity.” Quite a lot to digest. I will read it slowly.

Many of us have experienced and are building such Islands of sanity in the recovery community. Two weeks ago in Punta Gorda, Florida the CCAR Multiple Pathways of Recovery Conference was such a gathering of people from around the nation to nurture recovery community. I had a similar experience last Fall at the Mobilize Recovery convening in Las Vegas. The Association of Recovery Community Organizations through Faces & Voices of Recovery is another similar space. A theme of the conversations with people at these events is what do we do next to support additional recovery communities – I would call islands of healing around the nation. I think history has a few lessons for us on what works:

- Communities can and do best self-define their own manners of healing. One of the well-known stories I have heard Don Coyhis, founder of White Bison and the Wellbriety Movement talk about is a conversation he had with federal grant officers when his organization was initially awarded funding to support recovery for indigenous peoples over twenty years ago. He was told he had to use evidence-based practices in the grant. He noted that the Native American community had several thousands of years of evidence of what worked to heal their communities. Much to their credit, they listened not just to Don, but to other recovery community organizations in including their own expertise in strengthening their own communities. In this way, these grants helped form these islands of healing across America through the SAMHSA the initial Recovery Community Support Project grants. These are community up, not government down solutions that can greatly benefit from the support of the government but must be led by the recovery community. Look at what was accomplished, the approach worked. CCAR and many other RCOs who formed at that time are evidence of this very dynamic.

- If we want to build community-based services that meet the needs of our recovery community, we have to design funding around what works for these communities instead of trying to adapt healing processes to existing funding mechanisms. Recovery history shows us we tend to move away from community-oriented solutions as programming becomes institutionalized. We shift to fee for service funding models focused on individual units of care, following a clinical mentality. Instead of developing a deep understanding of what actually works, community-oriented programing is thus altered to meet existing funding mechanisms. These funding processes tend to favor large entities not grounded in recovery community. Community based recovery organizations try and use these funding mechanisms to serve their missions, but it often becomes a challenge as the focus becomes chasing these limited dollars and narrowing their missions to get paid for service units designed for clinical services.

- There is great interest in the national recovery community to build additional communities of healing. Many of my conversations with leaders nationally end up focusing on what we can do to advance efforts to heal communities using a recovery community up model. As I have mentioned in prior articles, I see a lot of room for consensus, but that the development of such consensus involves deep conversations, inclusivity and a lot of active listening. Readers of this post inside of government seeking ways to address our burgeoning addiction epidemic would do well to follow the wisdom of leaders like Dr. H. Westley Clark and the first grant officer of the SAMHSA RCSP grants Cathy Nugent who worked to bring these communities together and to start building these bridges of healing communities by listening to their experiential evidence of what works and helping to support them instead of redefining them to fit into some other model.

There are many of us across the county invested in building a care and support system that actually meets the needs of our respective communities. When I see the depth of interest in this issue, it brings me hope. Our mutual well-being will be largely dependent on how we can help nurture each other’s islands and support new islands built by people focused on healing their own communities. In a post titled Creating a Broad & Inclusive Recovery Plank I recently suggested that developing broad goals is a good place to start strengthening such bridge building efforts.

Perhaps we should form a recovery island bridge building coalition of similar minded communities that want to understand and develop common ground in between our islands and build bridges that span our differences. Here are three points to start such a conversation:

- Recovery communities are the experts on what is needed in their own communities. Recovery communities are diverse, and our efforts must be supported and funded equitably designed by us to serve our own communities.

- Discrimination and stigma against us must end. Systems that tokenize us are perpetuating discrimination. It is not acceptable to tokenize our voices. There has to be an accounting for how this has happened historically to marginalize us in order for healing to occur and for our society to reap the full benefits that a recovery orientated model of care can offer.

- How we do things matters. Our recovery communities are quite often vulnerable, and there are many groups, including some run by people in recovery that take advantage of our own people for material gain. We must establish a shared set of values and ethics and adhere to them to protect the most vulnerable among us.

So, to all the bridge builders of islands of recovery community – let’s find ways to develop consensus and understanding of each other and our experiential wisdom. If you disagree with my three points, I would love to hear yours, if those of us invested in bridge building listen to each other in this way, we will identify a common pathway forward!

It is true that when we come together, we are stronger. It is also true that the history shows us that we are most effective when we do so, even as there are so many forces that keep us arguing over small things. The truth is we do not need to have strong institutions to build consensus and community, we can do that with and for each other.

Please consider being a bridge builder between recovery communities, the island you strengthen may well be your own!

I watched an informational video about search patterns used by the Coast Guard and gained some thoughts I decided to share. The video was just under 30 minutes long and you can find it right here if you’re interested.

As you read this article, see what you notice from outside our field that could serve as hints to help improve our clinical work as addiction professionals.

What are we looking for and where is it heading?

The video I watched showed how Coast Guard search and rescue teams vary their search patterns and their use of search assets (ships, planes) according to:

- the type of object they are looking for;

- the size of object;

- the height and amount of visible surface area of the object above the surface of the sea;

- and “drift”.

As an example, they noted a person wearing a life jacket will float differently from a disabled flat-bottom boat.

Interestingly, they said that drift of the object will vary according to the total of the ocean current at the surface, the deeper current, and the wind. And they clarified that the different currents and wind might each be flowing in the same direction, or different directions.

To me all of that was fascinating and I started to consider possible areas of application for our work. Among other things, I asked myself things like: “As addiction professionals, what is it we are looking for and why? And where is the patient heading?”

Is our work complicated enough? Are we letting science help us?

The search crew stated that all the relevant data about the different currents and the wind are put into a computer. And the software then generates a tailored search pattern for that specific scenario. And the pattern is given to the air assets, ships, and personnel conducting the search.

- They stressed that different things float differently, and the atmospheric and ocean currents and conditions also differ.

- And they stressed the fact that all the relevant Coast Guard staff experience standardized training, so they will all understand the same things and follow the same procedures.

Again, I started to think about our work. Among other things, I wondered if we have made our work complicated enough, and if we as a field are really letting science help us like we could.

Best-practice, structured methodology? That also champions the patient?

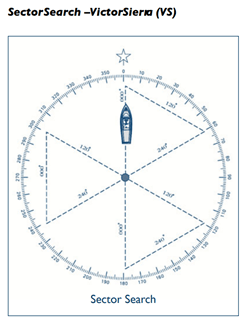

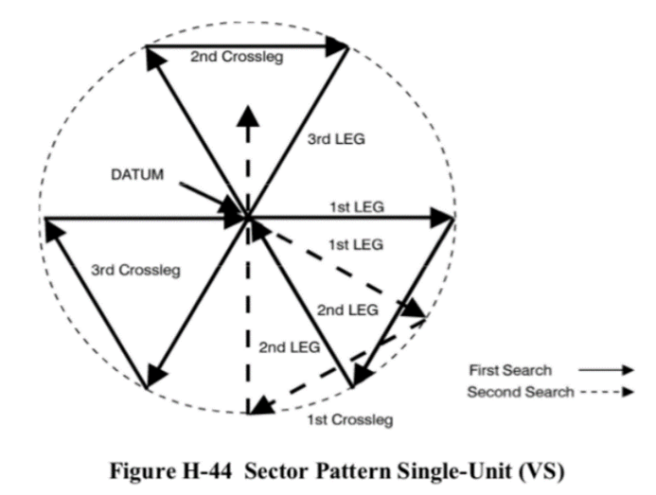

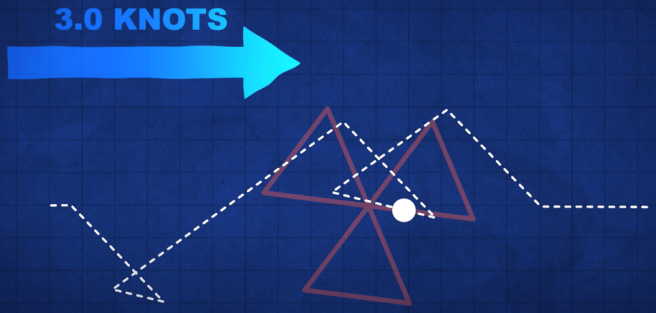

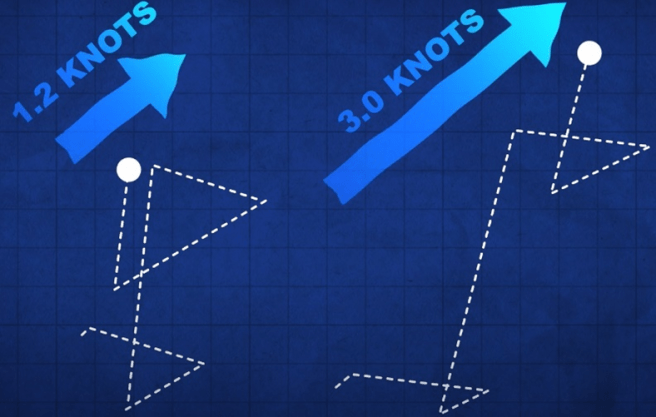

In the video, the “Victor Sierra” search pattern was featured.

The Victor Sierra search strategy is used to look for a small object in a relatively small location where the probability of the object being within that location is relatively high. The pattern is built from 3 isosceles triangles. It was initially odd to me, but rather interesting.

https://ccga-pacific.org/files/library/Chapter_9_Search.pdf. Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

During the use of the Victor Sierra search pattern, one of the crew is assigned to look out the left side of the vessel, one the right side, and one out the front – visually covering the entire search area in a thorough and reliable way.

But before the search begins the direction that the object is moving in is determined. And the direction is determined from the combination of the wind and both shallow and deeper currents.

That combination is used to understand the movement of the object being searched for, and also for a buoy they call the “datum”. The datum is placed in the water and left free to float and move on its own according to the wind and currents – just like the object being searched for.

The word “datum” is fascinating to me because it indicates a single reference point. The presenter noted that in engineering “datum” is the reference point from which one measures other things.

http://wow.uscgaux.info/Uploads_wowII/070/SEARCH_and_RESCUE-A_Guide_for_Coxswains_May_2020.pdf Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

But in this case the datum is literally a moving thing, not a fixed or stationery thing. And its motion (direction and speed) are the sum of the wind, shallow current, and deep current.

They went on to say that the search vessel’s initial motion is always in literal line with the movement of the datum.

Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

Interestingly, once the datum is deployed in the water, the ship backs away from it – in order to not effect it or its movement. The angles of the search pattern are then followed at a fixed rate of speed, at a set distance for each, and completed in a certain order.

As I watched the video, I saw many metaphors related to our work. And I asked myself many questions. For example, “Do we have a nationally-normed, universally applicable, best-practice structured methodology to guide us? One that champions the patient as the center?”

How person-centered are we?

Interestingly, the order in which the segments of the search are completed is static, but that order does not complete one full triangle at a time.

How is the search pattern followed?

- The first leg of the search starts from the location of the datum and is in the direction of the wind/water as crew can best determine.

- Once that first leg of the search is completed, the next angle is calculated from the location of the end of the first leg.

- Following the completion of this second leg, the ship heads directly back to the datum, and this is not done on a preset or calculated heading. Rather, the crew visually locates the datum and drives straight to it.

- Once they physically reach the datum, the direction/degree/angle of the next leg of the search is then determined.

As the search proceeds in this way, the search pattern is kept integrous by repeatedly returning to the datum, rather than making successive calculations from calculated locations. And in this way each new search angle moves with the natural combined movement of the wind and water.

I personally found the level of structured methodology and intentional freedom in the planned work they describe greatly inspiring.

And I asked myself if it is realistic to anticipate in the future:

- a universally available set of best-practice structured methodologies;

- that champion the patient;

- created for us on a normed basis;

- and specifically tailored to the particulars of the current person and their situation.

I ask myself if we are willing to be guided in the most expert way possible?

Messy inconsistency or a combination of expertise and natural forces?

Given drift, the lines that are ultimately searched do not form triangles. This is because the search lines move in time, congruent with the buoy.

By contrast, if the buoy did not move, the course of the search craft would simply replicate the pre-set triangular pattern. But it never does. The actual final shape of the search pattern is non-intuitive and always reflects the actual current/wind.

The shape of the search pattern will differ with the rate of the drift. The search moves with the current.

- For me, the wind is the manifest content of the life of the patient.

- And the water current is the latent content of the life of the patient on both shallower (more accessible) and deeper (less accessible) levels.

- And for me, the buoy reminds me of the person we are searching to help – who is always moving and provides us our center of reference.

This portion of the video made me wonder if we should consider a return to that center each time we complete our immediate purpose, and before we chart our next clinical move.

And it made me think about how our work appears from the outside. For example, does such work reflect messy inconsistency when viewed from the outside? Or does our work trace the combination of expertise and natural forces when viewed from the inside?

Appreciating drift, rescue, and what comes after rescue

The Coast Guard staff informed the film maker that wind and water are often aligned differently or may even be in opposition. They noted that these may all differ from each other due to the differing forces that produce each of them separately. To me, that fact alone is interesting and informs our work.

And they added that the most important task is the first task – determining the “set” and “drift” of the buoy. They stated that “set” refers to the direction of the buoy and “drift” refers to the speed of the buoy.

Once the starting center point of the pattern is established, the direction for the first leg of the 3 triangles is determined by going with the elements, not against them. They also stated that once the speed of the craft is set, it is not changed. Rather they, “Let the current take us.”

- To me this shows us the value of person-centered methods.

And to me this illumines areas of possible struggle for professional workers in our field. For example, do we choose:

- the datum (strictly person-centered reality) as our only reference point;

- the lighthouse that we might need to move toward once the rescue has been accomplished as our reference point; or

- the north star of long-term improvement as our reference point?

Which reference location do we use in the current moment? Or should we combine reference locations? Or at times oscillate between them?

For our work, would we only and always choose the location of the datum as the imagined destination of “full recovery 5 years after the last clinical touch”? Or should we always and only place it and leave it at the epicenter of the person served?

Or could the location of the datum be different, at different times, for different or changing purposes?

- If the epicenter of our work is the person served, then the patient is the reference point.

- If the epicenter is an imagined and much-fuller quality of life, is our effort meaningfully sufficient using that and only that long distance improvement as our only reference?

- But even then, who should define the hoped-for final location, and when, and on what terms?

And speaking of location, what about wind, shallow currents, and deep currents – at the location of the patient’s home or newer waters once they arrive safe? Are we also building safe-harbor locations in our society and larger communities? Do we appreciate all three of: drift, rescue, and what comes after rescue?

Science and compassion?

To conclude I’ll say that I imagine clinical work that includes:

- inputs from the patient, family members, clinical workers, and research scientists;

- reference points including the current condition of the person we serve contextualized by environmental conditions as they are;

- incremental markers to a safe harbor; and

- much farther true-north type wellness goals.

And I imagine our work both moving toward, and rotating on or pivoting against, pairs or groups of these markers (rather than only using one passive reference point) in best-practice algorithms, as we proceed.

Bob Lynn has summarized his aim for our work as “science and compassion”.

Hopefully this article has presented a framework and some considerations inspiring addiction professionals toward that aim.

Suggested Reading

Behavioral Health Recovery Management: A Statement of Principles.

Hofmann, S. G. & Hayes, S. C. (2018). The Future of Intervention Science: Process-Based Therapy. Clinical Psychological Science. 7(1): 37-50. doi.org/10.1177/2167702618772296

Proctor, S.L, Llorca, G.M., Perez, P.K. & Hoffmann, N.G. (2016). Associations Between Craving, Trauma, and the DARNU Scale: Dissatisfied, anxious, restless, nervous, and uncomfortable. Journal of Substance Use. DOI:10.1080/14659891.2016.1246621

A version of this post was originally published in 2018 and is part of an ongoing review of past posts about the conceptual boundaries of addiction, the disease model, and recovery.

The narrative that the opioid and overdose crisis is a product of despair has become very popular. The logic is that people in bad economic conditions are more likely to turn to opioids to cope with their circumstances and that their hopeless environmental conditions make them more likely to die of an overdose. This model frames addiction and overdose as diseases of despair.

This model fits nicely with other writers who have garnered a lot of attention on the internet.

- Johann Hari presents addiction as a product of a lack of connection to others.

- Carl Hart frames sociological factors as causative and argues that there’s a rationality to escaping terrible circumstances via drug use and that a form of learned helplessness eventually takes root.

- Bruce Alexander is frequently cited to support these theories. He did the “rat park” study that found rats deprived of stimulation and social interaction compulsively used drugs, while rats in enriched environments did not.

These understandings are so intuitive, but what if they are wrong?

These narratives make so much sense, and they support other beliefs and agendas many of us hold. Further, it feels like no one is going to harmed by efforts to improve economic, social, and environmental conditions, right?

Well, that’s not quite true. Bill White pointed out that how we define the problem determines who “owns” the problem, and that problem ownership has profound implications for addicts and their loved ones.

Whether we define alcoholism as a sin, a crime, a disease, a social problem, or a product of economic deprivation determines whether this society assigns that problem to the care of the priest, police officer, doctor, addiction counselor, social worker, urban planner, or community activist. The model chosen will determine the fate of untold numbers of alcoholics and addicts and untold numbers of social institutions and professional careers.

The existence of a “treatment industry” and its “ownership” of the problem of addiction should not be taken for granted. Sweeping shifts in values and changes in the alignment of major social institutions might pass ownership of this problem to another group.

White, W. L. (1998). Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, page 338

With so many bad actors in treatment right now, there is not a great rush to protect the treatment industry.

To be sure, we’d be better off of a significant portion of the industry disappeared. However, the disappearance of specialty addiction treatment would be tragic for addicts and alcoholics in need of help.

Further, it just so happens that there’s good reason to doubt the “diseases of despair” narrative.

New study casts doubt on “diseases of despair” narrative

A new study looked at county level data and examined the relationship between several economic hardship indicators and deaths by overdose, alcohol-related causes, and suicide.

Mother Jones describes the findings this way:

Economic conditions explained only 8 percent of the change in overdose deaths from all drugs and 7 percent of the change in deaths from opioid painkillers—and even that small effect probably goes away if you control for additional unobservable factors. It explained none of the change in deaths from heroin, fentanyl, and other illegal opioids.

Rising Opioid Deaths: Is the Cause Economic Despair Or Skyrocketing Supply? by Kevin Drum in Mother Jones

They quote the researcher as observing:

Such results probably should not be surprising since drug fatalities increased substantially – including a rapid acceleration of illicit opioid deaths – after the end of the Great Recession (i.e. subsequent to 2009), when economic performance considerably improved.

Rising Opioid Deaths: Is the Cause Economic Despair Or Skyrocketing Supply? by Kevin Drum in Mother Jones

If it’s not economic hardship, what is it?

Vox describes the study’s conclusions this way [emphasis mine]:

. . . the bigger driver of overdose deaths was “the broader drug environment” — meaning the expanded supply of opioid painkillers, heroin, and illicit fentanyl over the past decade and a half, which has made these drugs much more available and, therefore, easier to misuse and overdose on.

Why a better economy won’t stop the opioid epidemic by German Lopez in Vox

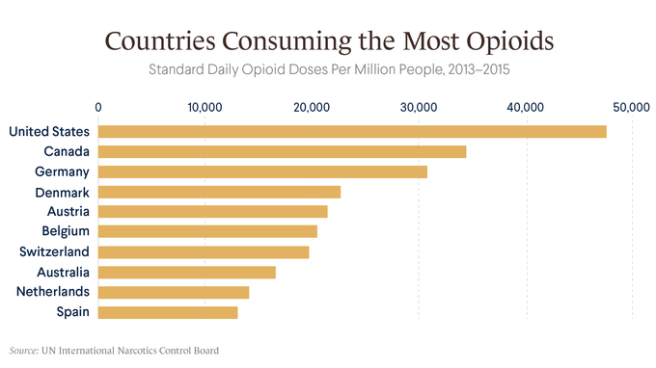

Leonid Bershidsky from Bloomberg noted the following:

The absence of an opioid epidemic in Europe indirectly confirms Ruhm’s finding. European nations have experienced the same globalization-related transition as the U.S. In some of them — Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, even France — economic problems were more severe in recent years than in the U.S. Yet no explosion of overdose deaths has occurred.

. . .

There’s also a notable difference in what substances are causing overdose deaths. In the U.S., heroin accounted for 24 percent of last year’s overdose deaths. In Europe in 2018, its share of the death toll was 81 percent. That should say something about how supply affects the outcomes.

Supply, Not Despair, Caused the Opioid Epidemic by Leonid Bershidsky in Bloomberg

Piling on

Then, as if to drive the point home, BMJ posted a study examining the relationship between opioid exposure and misuse. They looked at post-surgical pain treatment,

Each refill and week of opioid prescription is associated with a large increase in opioid misuse among opioid naive patients. The data from this study suggest that duration of the prescription rather than dosage is more strongly associated with ultimate misuse in the early postsurgical period. The analysis quantifies the association of prescribing choices on opioid misuse and identifies levers for possible impact.

Brat G A, Agniel D, Beam A, Yorkgitis B, Bicket M, Homer M et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study BMJ 2018; 360 :j5790 doi:10.1136/bmj.j5790

The study “excluded patients with presurgical evidence of opioid or other non-specific forms of misuse in the six months before surgery.” (I would have liked more stringent exclusionary criteria, but it’s still instructive.)

Where does this leave us?

I’ll repeat (a modified version of) what I wrote in a post in response to Johann Hari’s TED talk that emphasized lack of purpose and connection as the cause of addiction and add economic factors to the mix.

- Do economic/social/environmental factors cause addiction? No.

- Are they important? Yes.

- Do they influence the onset and course of addiction? Yes.

- Do they influence the access and responses to treatment? Yes.

- Is addressing those factors important in facilitating recovery for many addicts? Yes.

- Do economic/social/environmental factors cause addiction? No.

Ok, but what about policy?

This leaves us with some uncomfortable (but obvious, to anyone paying attention to this crisis) findings to consider.

Much of the policy discussion over the last several years has been dismissive of supply as a factor in addiction. This poses very serious concerns about that stance.

I’ve never been dismissive of supply as an important consideration, but I am coming to believe that I’ve underestimated its importance.

A lot of that dismissiveness is in response to the drug war and the moral horror of mass incarceration.

The problem demands more of us than we are typically capable of. We need to figure out how to address illicit and licit supply without resorting to mass incarceration AND assure treatment of adequate quality, duration, and intensity.

Update

A friend shared this Recovery Research Institute summary of epidemiological data on Substance Use Disorders. (I wish they wouldn’t use addiction and use disorders interchangibley.)

The provide data on SUDs by income, education, geography, age, gender, urban/rural, etc. I don’t see support for the disease of dispair narrative in their epidemiological data. Check it out here.

Holly Paulsen says the word SMARToon was coined by a participant in the specialized veterans and first responders (VFR) meetings created a little more than a year ago. It combines SMART and platoon to indicate a large group of individuals working together toward a common goal. And that is exactly what VFR is (with the name including military overtones): a group of individuals using SMART’s practical tools and mutual support to address their addictions–together.

Paulsen is a participant and facilitator in the meetings, and a US Army veteran who served for eight years. She says she started drinking in earnest at age 17 when a local bar near her duty station expressed the belief that “if you’re old enough to serve, you’re old enough to be served.” Real trouble began a few years later when her drinking became a way to self-medicate her untreated PTSD.

Although Paulsen jokes that because her sober date is April 1, 2013, she might advise others that making a major life change on April Fool’s Day is tricky because people might not believe you. But when it comes to helping herself and others through VFR meetings, she is altogether serious. Paulsen loves the meetings, believes in the cause, and, along with the other members of the SMARToon, thinks they’re only getting started when it comes to making a positive impact in the field of recovery.

Paulsen recently answered a few questions about her experience and thoughts about what she is doing.

How long have you been attending VFR meetings?

I’ve attended the VFR meetings since the very first one on November 10, 2020. I was early to a [different] 7:30 EST meeting and happened to see a VFR meeting that I hadn’t noticed before. I figured I’d give it a try—it just so happened to be the very first VFR meeting!

Did you have any concerns before you got started?

Honestly, the thought of having a room full of individuals who understood my unique experiences excited me more than anything. Like any group, I was reluctant to share at first, but the group quickly became my home and the participants, my family.

How have they grown since you’ve been involved?

What started out as one small discussion meeting has grown into three weekly discussion meetings—one of them women only—and a practical tool-time meeting as well. We have aspirations and are making preparations to expand our frequency and reach even further.

What is the most rewarding thing you get out of them?

As our meetings have grown, the number of volunteers that have been spawned from those meetings has skyrocketed. That’s important for SMART’s overall growth. When a member begins to express interest in helping with our meetings, we are always quick to reach out and support them in any way we can through their training. We work better when we work together and we thrive when our members thrive.

What kind of challenges have there been?

I think the biggest challenge for our participants—me included—is asking for and accepting help. Our participants have dedicated their lives to serving others. It’s second nature for us. Being the one in need of support is unfamiliar territory and can be a struggle.

What is an example that illustrates how valuable someone might find the meetings?

Early in the VFR meetings, I began to repeat a quote that I found significant. As a veteran who’s lost countless of my brothers, sisters, and others to suicide, I found the need to reach out to those who may be in crisis and looking for even the tiniest glimmer of hope to hang onto. So, I began stating, “If you’re looking for a sign not to do it, this is it,” on the off chance someone was truly looking for any sign not to end their life. The first time someone reached out to tell us that they had been looking for a sign that night and the words had stopped them, it was a lot to process. To know that someone is still with us today is overwhelming in the best possible way.

What do you hope will happen with the meetings?

In a perfect world, we would love to see a VFR meeting of some kind seven days a week. There is no doubt in my mind that the “SMARToon” will accomplish this. The men, women, and others in our meetings are the most selfless and dedicated individuals I have ever had the honor of meeting. I don’t foresee us stopping there, either. SMART Recovery is global. I see no reason the “SMARToon” won’t eventually be as well. It’s not a dream for us. It’s an eventuality!

With the momentum already established and the people in place to keep it moving, it’s a safe bet that Paulsen and her SMARToon will get it done. Double-time.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

A version of this post was originally published in 2016 and is part of an ongoing review of past posts about the conceptual boundaries of addiction and its relationship to the disease model and recovery.

I’ve had a lot requests to respond to this recent piece in the NY Times.

A Personal Narrative or Universal Model?

The piece is really interesting and engaging description of the author’s personal experience. I get the impression that she’s frustrated that most people would say that her experience with heroin means she has the disease of opioid addiction. She does not believe she has a disease and doesn’t want to be shoehorned into that model. So, she’s offering an alternative framework to explain her experience.

She believes her drug problems were a result of disordered learning, self-medication, and something akin to a love relationship with the relief that heroin provided.

I can imagine it’d be frustrating to be shoehorned into a model that doesn’t fit one’s experience. The problem is that she constructs a model of understanding addiction from her personal experience—an experience that seems fairly atypical—and then presents it as a model for understanding addiction in general.

Addiction as a Category

It’s important to point out that I don’t believe the author uses the same definition of addiction I do. I limit the term addiction to people with chronic and high severity substance use problems characterized by impaired control—most people with drug problems do not have addiction.

In a previous post, I took a long look the categorization of substance use problems. In that post, I made the case for addiction as a different kind of problem from less severe substance use problems rather than a more severe version of the same problem.

Dependence was far from perfect. This is not an argument for a return to the abuse/dependence model. (Though I will argue that we should return to conceptualizing as addiction as a different kind of problem from low to moderate SUDs, rather than a different severity.)

Let’s start by stating that addiction/alcoholism is the chronic form of the problem is primary and characterized by functional impairment, craving and loss of control over their use of the substance.

Problems with the categories of abuse and dependence include:

- Dependence has often been thought of as interchangeable with addiction/alcoholism, but this is not the case.

- Dependence criteria captured people who are not do not have the chronic form of the problem. We know that relatively large numbers of young adults will meet criteria for alcohol dependence but that something like 60% of them will mature out as they hit milestones like graduating from college, starting a career or starting a family.

- Dependence criteria captured people who are not experiencing loss of control of their use of the substance.

- The word dependence leads to overemphasis on physical dependence which, in the case of a pain patient, may not indicate a problem at all.

- The word abuse is morally laden.

- For me, there are serious questions about whether abuse should be considered a disorder at all.

Several of these problems are related to doing a poor job in distinguishing which kind of user the patient or subject is.

The abuse/dependence model fell short in distinguishing between kinds of users. Rather than taking a step forward in distinguishing between the kinds of users, the continuum approach implies that there is only one kind with different levels of severity.

In that post, I also pointed out that framing addiction as a more severe version of the same problem would undermine the disease model.

The continuum approach becomes especially troubling when you think about the idea of giving people with low severity SUDs and people with the disease of addiction the same diagnosis, only with different severity ratings.

There’s little doubt that large numbers of young people on college campuses meet diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder under the DSM 5. I doubt anyone would argue that all of these young people have a disease process? Even a mild one?

This seems likely to undermine the acceptance of addiction as a disease. Not just by the public, but also by insurers and policy makers.

So, it’s not surprising that she’s using the broader definition of addiction when questioning the disease model.

Addiction as a Learning Disorder

I don’t at all disagree that addiction involves disordered learning.

However, I would disagree that addiction is only (or primarily) disordered learning. Addiction is disordered learning AND much more.

The idea that learning plays a role in addiction is not new. The American Society of Addiction Medicine definition of addiction includes the following. (Keep in mind that references to memory speak to learning.)

Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors.

Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Addiction affects neurotransmission and interactions within reward structures of the brain, including the nucleus accumbens, anterior cingulate cortex, basal forebrain and amygdala, such that motivational hierarchies are altered and addictive behaviors, which may or may not include alcohol and other drug use, supplant healthy, self-care related behaviors. Addiction also affects neurotransmission and interactions between cortical and hippocampal circuits and brain reward structures, such that the memory of previous exposures to rewards (such as food, sex, alcohol and other drugs) leads to a biological and behavioral response to external cues, in turn triggering craving and/or engagement in addictive behaviors.

The neurobiology of addiction encompasses more than the neurochemistry of reward.1 The frontal cortex of the brain and underlying white matter connections between the frontal cortex and circuits of reward, motivation and memory are fundamental in the manifestations of altered impulse control, altered judgment, and the dysfunctional pursuit of rewards (which is often experienced by the affected person as a desire to “be normal”) seen in addiction–despite cumulative adverse consequences experienced from engagement in substance use and other addictive behaviors. The frontal lobes are important in inhibiting impulsivity and in assisting individuals to appropriately delay gratification. When persons with addiction manifest problems in deferring gratification, there is a neurological locus of these problems in the frontal cortex. Frontal lobe morphology, connectivity and functioning are still in the process of maturation during adolescence and young adulthood, and early exposure to substance use is another significant factor in the development of addiction. Many neuroscientists believe that developmental morphology is the basis that makes early-life exposure to substances such an important factor.

. . .

In addiction there is a significant impairment in executive functioning, which manifests in problems with perception, learning, impulse control, compulsivity, and judgment. People with addiction often manifest a lower readiness to change their dysfunctional behaviors despite mounting concerns expressed by significant others in their lives; and display an apparent lack of appreciation of the magnitude of cumulative problems and complications. The still developing frontal lobes of adolescents may both compound these deficits in executive functioning and predispose youngsters to engage in “high risk” behaviors, including engaging in alcohol or other drug use. The profound drive or craving to use substances or engage in apparently rewarding behaviors, which is seen in many patients with addiction, underscores the compulsive or avolitional aspect of this disease. This is the connection with “powerlessness” over addiction and “unmanageability” of life, as is described in Step 1 of 12 Steps programs.

Is addiction a disorder of learning? Yes. But, it’s also a disorder of genetics, motivation, reward and stress.

Dirk Hanson has written eloquently on the convergence of thinking of addiction as a learning disorder and muddying the distinctions between problem use and addiction.

For harm reductionists, addiction is sometimes viewed as a learning disorder. This semantic construction seems to hold out the possibility of learning to drink or use drugs moderately after using them addictively. The fact that some non-alcoholics drink too much and ought to cut back, just as some recreational drug users need to ease up, is certainly a public health issue—but one that is distinct in almost every way from the issue of biochemical addiction. By concentrating on the fuzziest part of the spectrum, where problem drinking merges into alcoholism, we’ve introduced fuzzy thinking with regard to at least some of the existing addiction research base. And that doesn’t help anybody find common ground.

Addiction as Love and Self-medication

Addiction as an unhealthy form of attachment or love is also not a new idea. Stanton Peele, a gadfly and long time critic of the disease model wrote the following:

An addiction may involve any attachment or sensation that grows to such proportions that it damages a person’s life. Addictions, no matter to what, follow certain common patterns. We first made clear in Love and Addiction [published in 1975] that addiction— the single-minded grasping of a magic-seeming object or involvement; the loss of control, perspective, and priorities—is not limited to drug and alcohol addictions. When a person becomes addicted, it is not to a chemical but to an experience. Anything that a person finds sufficiently consuming and that seems to remedy deficiencies in the person’s life can serve as an addiction. The addictive potential of a substance or other involvement lies primarily in the meaning it has for a person.

Theories of addiction as a form of self-medication have been about for decades. These theories frame addiction as secondary to another problem which may be social, psychological, environmental or physical in nature.

However, addiction is widely accepted as a primary disease among professional societies.

Further, addiction’s (I’m referring to severe and chronic substance use problems.) onset, course and response to treatment is often affected by social, environmental, psychological and physical problems, but it generally does not fade away when those problems are addressed.

Multiple Mechanisms

The more we learn about addiction, the more we find that there are multiple mechanisms involved. In a 2011 post, I wrote the following (keep in mind that this is abstract speculation rather than a concrete theory):

Or, maybe there are several neurological mechanisms (reward pathway, memory circuits, risk evaluation, self-regulation, stress responses, etc.) and some people may have 2, others may have 6. Some factors may be associated with a more chronic form, others may be associated with a more severe loss of control and overall severity may be associated with the number of factors the person has. (Some might be primary to addiction, others secondary.)

There are probably a lot more than 6 but, for the sake of argument, let’s stick with 6. So, is it possible that the author had 1, or 2 or 3 of these mechanisms (ones involving memory, attachment and learning) while most people with addiction (chronic and severe) suffer from 5 or 6?

Could this provide a way to view her model as true for her (and some others) and the disease model as true for most people with addiction? I think it might. And, maybe it could also shed some light on a portion of that segment of young, heavy users who mature out.

It’s not that she’s wrong. It’s just that she’s zooming in on one part of a larger story to the exclusion of the rest of what we know.