It was suggested to me to post my testimony at the state hearing here. There is a link to a PDF of it at the end of the document

Senate Democratic Policy Committee Hearing

Recovery Issues & Improvements

January 20, 2022, at 10 AM

Testimony on Recovery Funding

William Stauffer LSW, CCS, CADC

Recommendations and Overview of PRO-A & Recovery Community Organizations

I want to thank the Senate Democratic Policy Committee for including me here today. To start, the most underutilized resource we have to support addiction recovery are the thousands of Pennsylvanians in recovery and our grassroots Recovery Community Organizations (RCO)s which are authentic, independent, non-profit organization led and governed by representatives of communities of recovery, who understand and live recovery from addiction every day. Programs like Easy Does It in Berks County, or the PRO-ACT Montgomery County Recovery Community Center. Recovery is contagious – lets fund, support, strengthen, and spread it!

Overview:

- Having run the stakeholder group who made recommendations on recovery house standards, we are concerned that the new recovery house regulations have created conditions in which the thousands of marginalized people who use this housing in early recovery will not be able to afford to live in them.

- As a result of our recent efforts, we are pleased that our Department of Drug and Alcohol has identified through the Recovery Rising that the recovery community has not been funded or included in meaningful ways historically. This encompasses all recovery support services, including how recovery houses are funded and implemented. The Recovery Rising process can improve policy if conducted in truly inclusive ways open to addressing the disparate funding and exclusion of our voices in matters that impact our community.

- While addiction is one of our costliest social challenges in resources and lives, we also know that 85% of the people who reach five years of addiction recovery remain in recovery for the rest of their lives. We should focus on long term recovery as our functional system metric for severe substance use disorders (SUD).

- Policy has focused on short-term treatment and harm reduction strategies, critical, lifesaving elements of an effective care system, yet we have seen minimal investment in community-based recovery efforts. If we expanded investment in long term recovery in ways that meet the needs of the recovery community, we could save more lives, strengthen families, and heal communities.

- Strong, effective policy and interventional strategies are best developed by, and in true collaboratively partnerships with the recovery community organizations that focus on strengthen recovery capital, including recovery housing and other recovery services in these communities and expand our recovery capacity through our statewide recovery community organization.

Recommendations:

- We should independently examine the implementation of the recovery house regulatory standards and their impact on the working poor recovery community that depends on this form of housing.

- Similar to how we support veteran centers and senior citizen centers, we should fund 12 recovery community organizations across Pennsylvania with technical assistance funded and provided through our statewide recovery community organization to strengthen this neglected but critical resource.

- Statewide SUD peer training has been sole sourced by DDAP through a closed door, no bid process, shutting down the marketplace, setting up a gatekeeper model beyond stakeholder input. It has already increased workforce barriers for our whole SUD system and this sole sourced training process should be eliminated.

- Programming for SUDs tends to become punitive, over bureaucratized, and ineffective over time due to the subtle impact of implicit bias that influences how are systems address treatment and recovery needs. The recovery movement in America has focused on reestablishing our roles in these same systems. Our rallying cry, NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT means that no programming should be developed without the full and equitable participation of our recovery community. Elevating and funding RCOs to help develop policy, implement programming, and participate in evaluation would improve care and support for persons with SUDs in ways that reduce discrimination and increase the effectiveness of our entire care system.

Who am I

My name is William Stauffer, I have served in many capacities within our SUD treatment and service support system for well over 3 decades. I am a licensed social worker, certified clinical supervisor and certified alcohol and drug counselor, I teach at Misericordia University and train nationally, including for Faces & Voices of Recovery the national recovery community organization. I worked in and supervised a publicly funded outpatient treatment program for ten years; I ran a publicly funded longer term residential program for 14 years and have served as the Executive Director of PRO-A for 9 years. In 2018, I testified at the US Senate Hearing on Older Adults and the Opioid Epidemic in the Senate Committee on Aging at the invitation of ranking member Senator Bob Casey. In 2019 I assisted organizing and testified at a hearing on the lack of adolescent services in Pennsylvania for the House Human Services Committee and participated in a hearing on the impact of COVID-19 on our service system in 2020. I have written extensively on the recovery in America and how to strengthen our recovery efforts across the nation. In 2019, I was honored at the America Honors Recovery event in Arlington VA with the Vernon Johnson Award as the Recovery Advocate of the year award. I have experienced the loss of close family members to addiction, and I am also a person in long term recovery for over 35 years.

What is PRO-A – The Pennsylvania Recovery Community Organizations – Alliance (PRO-A)

We are the statewide RCO, a 501C3 started in 1998 with a mission to “mobilize, educate and advocate to eliminate the stigma and discrimination toward those affected by alcohol and other substance use conditions; to ensure hope, health and justice for individuals, families and those in recovery.” We have worked collaboratively to develop recovery initiatives across five PA administrations. We have over 5,000 members and membership has always been free. We provide education, training, and technical assistance across the state of Pennsylvania.

- The federal government modeled the very approach that led to the development of RCOs by acknowledging and supporting that people in recovery are the experts on recovery and honoring “community up” solutions.

- 24 states have statewide RCOs similar to PRO-A, many supported financially through state resources.

- We were born out of the national New Recovery Advocacy Movement, predicated on the belief that no policy or service should be developed without the full participation of the authentic recovery community.

- These concepts were historically embraced across our care systems and heavily influential in the development of Recovery Oriented Systems of Care (ROSC) in PA. It established collaborative efforts across several departments of government and with recovery community stakeholders over several decades.

- Peer recovery support services provided by authentic recovery community organizations remain a fundamental element of a recovery-oriented system of care vision in Pennsylvania and beyond.

- We had historically been modestly funded through our state Single County Authority the Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs but have not received any funding through DDAP since FY 2019.

Noted Work Conducted by PRO-A for the State of Pennsylvania

What is a Recovery Community Organization?

A recovery community organization (RCO) is an authentic, independent, non-profit organization led and governed by representatives of communities of recovery. These organizations organize recovery-focused policy activities, carry out recovery-focused community education and outreach programs, and/or provide recovery support services.

- There has never been an established, stable funding mechanism to support recovery community organizations in the state of Pennsylvania across all regions. Instead, funding is patchwork.

- People in recovery understand addiction and have lived experience of recovery. RCOs can support persons, families and communities struggling with addiction by fostering hope, purpose, and connection.

- Resources to fund technical assistance and anti-stigma efforts with state dollars are not being invested in our recovery organizations but instead are flowing out to national organizations or housed within academic institutions with no connection to or knowledge of our experience of recovery and facets of discrimination.

The History and Influence of Recovery Community Organizations

RCOs were funded by SAMHSA in the late 1990s. RCOs have changed the way America thinks of recovery. We introduced the notion of recovery focused care beyond traditional acute care treatment, developing peer support services and recovery messaging to help people move recovery out into the public’s eye. We want a care model to support long term recovery to heal individuals, families, and whole communities.

Until 2018, PRO-A’s collaborative work with our Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs (DDAP) had historically been central to its state plan (page 11):

“Recovery is the foundation of DDAP’s work on behalf of individuals and families experiencing drug and alcohol problems. With recovery as a cornerstone of DDAP’s work, it is essential that we support and promote the statewide recovery organization to ensure that we continually have representation of the faces and needs of the individuals and families that we exist to serve distinct from stakeholders in the direct service arena. It also provides a mechanism to engage and support individuals and groups across the Commonwealth concerned about the issues of addiction and recovery.

Fragmented Recovery Community Funding

Funding for recovery community organizations has historically been quite limited. RCOs that have been able to develop have done so by cobbling together patchwork grants and service initiatives to support their missions. To strengthen recovery efforts, we need sustainable ways to develop and fund these vital community programs

- SAMHSA had long offered grants RCSP on the federal level to support RCOs to develop these models, which have greatly improved how we conceive of recovery and provide SUD care and support in America.

- There has been investment in peer services provided by Certified Recovery Specialist and Certified Family Recovery Specialists through health choices reinvestment dollars and the Center Of Excellence programs.

- Some Single County Authorities (SCA)s have chosen to support recovery community organizations. In their respective communities, we are seeing the benefits of this investment in building recovery capital.

- DDAP has offered several time limited peer service grants offered competitively across Pennsylvania for services to recovery support services, but these grants have largely gone to established human service organizations. They have not been focused on the strengthening of recovery efforts at the community level developed and provided by recovery community organizations steeped in recovery.

- Even as funding has increased, one BIPOC (Black and Indigenous people of color) run RCO that operated for 2 decades closed in the last year for lack of funding and another receives zero support public dollars.

- Grassroot RCOs are often funded through bake sale and spaghetti dinner type funding drives supported by their local community and not within our established care system because funding has not been established for them in a cohesive and sustainable way at the state or regional levels.

- Peer training for Certified Recovery Specialists were initially developed with regional RCOs by PRO-A, our statewide RCO. Last year, DDAP awarded noncompetitive funding to a private organization to take over all peer training in both the public and private sectors. Training for peer workers can now only be done through this new gatekeeper model funded with public dollars. Training requirements can now be changed by this private entity with no input from SUD stakeholder groups creating a system wide workforce barrier.

- The requirements for SUD peer training are perhaps now the most arduous in the nation. They are subject to being changed in ways that impact our entire SUD care system workforce due to this closed-door process eliminating our training marketplace and awarding the facilitation of all public and private training for SUD peer workers to this single entity outside of a system of oversight, checks and balances.

Our Policies and System Orientation Have the Wrong Focus

There is some national recognition that we have failed to focus on flourishing for persons with addiction. In a February 2019 Op-ed for the Journal Alcohol & Drug Dependence, senior editor Dr. Eric Strain noted that “our failure to forcefully advocate that patients need to flourish is tacitly acknowledged through interventions such as low threshold opioid programs, provision of naloxone with no follow up services, and buprenorphine providers who only offer a prescription for the medication.” He suggests that we need to engage patients to support flourishing and provide meaning, a fundamental human need. This is a facet of a recovery-oriented system.

- Research and historic efforts to support wellness has focused on addiction, not on recovery. We need to shift our focus to recovery to heal our loved ones, families, and communities.

- In an Op-Ed for STAT news in early 2020, I noted that “few Americans get anywhere near 90 days of care. Within the confines of existing insurance networks, short-term treatment of 28 days or less is all that most Americans are offered — if they can get any help at all. This ultimately reflects the soft bigotry of low expectations: an inadequate care system designed to deliver less than what people need because we still moralize addiction and do not value people who have substance use disorders.”

- If we want to improve our outcomes, we need to change our measures to focus on recovery and not a single facet of addiction or a short-term outcome.

What is the Five-Year Recovery Paradigm?

The five-year recovery paradigm was started by Dr. Robert DuPont, former Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy and primary investigator of the first national study of the physician health programs (PHPs) which produced impressive long- term outcomes for individuals with severe SUDs. This has evolved into the conception of the “New Paradigm” for long-term recovery with goal of five-year recovery for all SUD treatments including all types of programming and recovery support services with a clear shared goal of long-term recovery. We should focus our efforts across harm reduction strategies, SUD treatment and recovery support services on their ability to produce sustained recovery for persons with severe SUDs.

Focus on Long Term Recovery Outcomes

We should change our lens to focus on long term recovery to strengthen our recovery community.

- “The National Institute on Drug Abuse Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment defines 90 days across levels of care as the minimum threshold of care below which recovery outcomes begin to deteriorate. Of all those discharged from addiction treatment who will resume drug use in the following year, most will do so in the first 90 days following discharge.” Article, Bill White Recovery, the first 90 days.

- An study on the relationship between the duration of abstinence and other aspects of recovery found:

- Only about a third of people who are abstinent less than a year will remain abstinent.

- For those who achieve a year of sobriety, less than half will relapse.

- If you can make it to 5 years of sobriety, your chance of relapse is less than 15 percent.

- What it includes: “The shift to a model of sustained recovery management includes changes in treatment practices related to the timing of service initiation, service access and engagement, assessment and service planning, service menu, service relationship, locus of service delivery, assertive linkage to indigenous recovery support resources, and the duration of posttreatment monitoring and support” From article Recovery management: What if we really believed that addiction was a chronic disorder?

Funding Models – Peer Services vs Funding Recovery Community

We should establish sustainable funding mechanism that nestle recovery in recovery community centers run by recovery community organizations by and for the recovery community.

Funding Recovery Community Centers as a community resource:

- The end goal we should focus on is the strengthening of recovery capital to support long term recovery, which is an effective strategy to strengthen recovery. Recovery capital is the development of all the internal and external resource to support recovery at the individual, family, and community level.

- The best way to strengthen recovery capital is to invest in grassroot recovery community organizations that are focused on the development of these facets at all three levels, individual, family and community.

- We fund community centers and senior centers as community resources and not within the traditional fee for service model because they are community oriented and not a narrowly focused individual service.

The limitations of funding peer services provided as individual or group sessions at the individual level:

- Peer services can support the development of recovery capital at the individual level through existing fee for service models, but these tend to focus only on the individual and not family and community level support.

- The trap of fee for service funding structures is that some grassroot community organizations are often locked out of these provider networks and communities are not able to benefit from what they can offer.

- Even those RCOs who can navigate the fee for service structures end up getting stuck in a funding structure that results in the chasing of low reimbursement rates to stay open while narrowing their effective work to the individual, resulting in an erosion of their capacity to strengthen recovery capital at the community level.

Retooling substance use care to support long term recovery

Addiction is our most pressing public health crisis. The science is showing us that five years of sustained substance use recovery is the benchmark for 85% of people with substance use disorder (SUD) to remain in recovery for life. So why are we not designing our care systems around this reality?

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) identifies that the minimum dose of effective treatment is 90 days, yet far too few people get even that. Negative public perception about people with SUDs underpins much of our system problems – we ration care, regarding persons with SUDs as undeserving. As a result, fewer achieve lasting recovery than could. As SUDs impact one in three families, it is time we recognize these are “our” people and not “those” people and deserve our help. It makes sense and it saves resources.

We have seen that the opioid crisis alone caused a 2.8% reduction in our Gross Domestic Product. Alcohol use disorders still surpass opioid use disorders in annual fatalities. We are talking about a lot of resources spent shoveling up after untreated or undertreated SUDs. Despite these hard facts, we have set arbitrary limits on service, long wait times to access care, insurance denials for care as a norm, and a byzantine process for persons needing help to navigate treatment. People are often served at lower levels and shorter durations of care needed. Ironically, the person often feels like they failed, rather than the system failing to help them.

When a person gets a diagnosis of cancer, our medical system orients care to support multiple interventions, procedures, supports and checkups over the long term. If one approach does not work, we move to another. It is a chronic care model. Such a system is flexible, properly resourced and offers multiple pathways to health. The system coordinates care in a supportive manner through the disease process to get them to the day that they can celebrate five years in remission. This model is the model we need to orient to for severe SUD recovery.

When a person achieves five years in full remission from a SUD, the likelihood of remaining in recovery for the rest of their lives is around 85%. Achieving this standard of care across our service system requires expanding peer services and reorienting care to a long-term service model. It involves treatment assisted by medication, peer support services, family support and case management to help people get back into care quickly in the event of a lapse. People could obtain multiple services based on individual need, typically reducing in intensity over time. In the event of resumption of active use, people can access care in real time with no barriers.

A recovery oriented five-point plan to strengthen and heal our communities:

1. A service system that supports long-term recovery: Establishing and funding SUD treatment and long-term recovery support services that address the needs of the person, including co-occurring conditions/ issues, generally with decreasing intensity – over a minimum of five years.

2. A system that meets the needs of our young people: Develop Recovery High Schools, Collegiate Recovery Programs, and Alternative Peer Groups (APGs). Provide local family education, professional referral, and support programs to assist each young person with a SUD to sustain and support recovery for a minimum of 5 years.

3. Build the 21st Century workforce to serve the next generation: Develop stable funding streams, reasonable compensation, administrative protocols, and peer recruitment and retention efforts.

4. Although there are many social, employment, legal, educational, and other important issues with the person with a SUD, there are a couple of exceptionally important areas. Employment, education, and self-sufficiency are fundamental to healthy recovery and functional communities. We envision a network of employers that provide work opportunities for persons in recovery. We must expand college and trade educational opportunities while reducing and eliminating barriers to employment, like those posed by criminal records, for persons in recovery. There must be simple processes for persons to clear their records from past criminal charges as they attain stable recovery and are ready to become fully productive citizens.

5. Recovery housing opportunities: People in recovery need stable, supportive, and affordable transitional and long-term housing. We must develop a system of quality recovery houses. This system needs to include adolescent and special population housing, infrastructure development, and training for house operators to support recovery from a SUD. The housing system needs to work collaboratively to support long-term treatment and recovery as part of a system of care with a five-year recovery goal.

Link to PDF of Testimony – https://pro-a.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/00-PROA-Senate-Hearing-Testimony-Recovery-Funding-1-20-22.pdf

This post was originally published in 2012 and is part of an ongoing review of past posts about the conceptual boundaries of addiction and its relationship to the disease model and recovery.

In a thoughtful post, Marc Lewis questions the disease model of addiction.

He doesn’t dismiss it out of hand. He seems to look for ways in which it’s right and useful.

It’s accurate in some ways. It accounts for the neurobiology of addiction better than the “choice” model and other contenders. It explains the helplessness addicts feel: they are in the grip of a disease, and so they can’t get better by themselves. It also helps alleviate guilt, shame, and blame, and it gets people on track to seek treatment. Moreover, addiction is indeed like a disease, and a good metaphor and a good model may not be so different.

He offers two objections.

Spontaneous Recovery

First the existence of spontaneous recovery:

What it doesn’t explain is spontaneous recovery. True, you get spontaneous recovery with medical diseases…but not very often, especially with serious ones. Yet many if not most addicts get better by themselves, without medically prescribed treatment, without going to AA or NA, and often after leaving inadequate treatment programs and getting more creative with their personal issues.

My first reaction is that we’re not very good at distinguishing misuse, dependence and addiction. These studies include people who met diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence in college and reduced their use as they moved into other stages of life. The other frequently cited group are heroin dependent Vietnam vets. Again, it’s important to distinguish between dependence and addiction.

So, I think, the problem is not the disease model, but rather, our diagnostic categories and their application. I suspect that if those studies finding high rates of natural recovery limited subjects to those with true loss of control (addiction), the prevalence of spontaneous remission would drop dramatically.

Further, I’m not sure this this is a strong argument at all. Wouldn’t this exclude hundreds of viral and bacterial diseases? These are generally acute illnesses, but don’t other diseases have acute and chronic forms?

Dopamine responses are normal

His second objection is that addiction uses natural brain mechanisms that are shared by many other life experiences.

According to a standard undergraduate text: “Although we tend to think of regions of the brain as having fixed functions, the brain is plastic: neural tissue has the capacity to adapt to the world by changing how its functions are organized…the connections among neurons in a given functional system are constantly changing in response to experience (Kolb, B., & Whishaw, I.Q. [2011] An introduction to brain and behaviour. New York: Worth). To get a bit more specific, every experience that has potent emotional content changes the NAC and its uptake of dopamine. Yet we wouldn’t want to call the excitement you get from the love of your life, or your fifth visit to Paris, a disease.

I have a couple of thoughts about this. First, lots of diseases are characterized by natural body processes turning against the body, many cancers for example. Second, when we’re talking about addiction, we’re not talking about one brain mechanism. (He focused on dopamine release.)

Several brain mechanisms have been identified and, I suspect, better understandings of these will lead to better typologies for AOD problems. Some people may have only one or two of these neurobiological factors, while others have ten. Some factors may be associated with a more chronic form, others may be associated with a more severe loss of control and overall severity may be associated with the number of factors the person has. (Also, some might be primary to addiction, others secondary.)

What is a disease, anyway?

I think the biggest barrier to responding is that the writer did not offer a definition or boundaries for understanding “disease.” Merriam-Webster offers this definition:

a condition of the living animal or plant body or of one of its parts that impairs normal functioning and is typically manifested by distinguishing signs and symptoms

WebMD offers Stedman’s Medical Dictionary’s definition as:

A morbid entity ordinarily characterized by two or more of the following criteria: recognized etiologic agent(s), identifiable group of signs and symptoms, or consistent anatomic alterations.

Is the writer arguing that addiction does not meet these definitions? I’m having a hard time seeing how. And, why does the idea of classifying addiction as a disease bother people so much?

Related articles

Why Mindfulness?

Everyone at one point or another feels weighed down with negative thoughts and internal or external stressors in our day-to-day lives. However, the practice of mindfulness aims to provide an opportunity to put our minds at ease and focus on being in the present moment.

But what are t he true benefits of practicing mindfulness – especially as it relates to recovery? The reality is that mindfulness and recovery can be very closely intertwined, and recovery can often be made more successful by including mindfulness as an active, daily effort.

he true benefits of practicing mindfulness – especially as it relates to recovery? The reality is that mindfulness and recovery can be very closely intertwined, and recovery can often be made more successful by including mindfulness as an active, daily effort.

What are some noticeable benefits of practicing mindfulness?

Mindfulness can improve impulse control by improving the function of the prefrontal cortex. Your ability to “pause,” as taught in the 11th step, will improve. These changes can even be immediate, but practice needs to be consistent if permanent changes are to be made.

Mindfulness can improve one’s ability to manage cravings and triggers by increasing present moment awareness so that you can practice relapse prevention in the moment rather than when you notice that you are really in trouble. If you are practicing loving kindness meditation, it can improve your relationships with others so that you are more helpful and supportive in your recovery relationships.

How does recovery from substance use disorder and mental health go together?

Most people either begin drinking or using to manage their emotions, and eventually keep doing it because it makes them feel better. This need to feel comfortable is a natural human drive that exists without our awareness most of the time. This means that recovery from substance use and mental health must happen together for the best possible chance at success.

Mindfulness is an important tool for regulating emotions, so it can ultimately assist with recovery from substance use. There are also specific practices that can help detoxify the body from both mental and physical effects of substances that will aid in overall recovery. Ultimately, recovery that does not include a focus on improving mental health will not be successful long term.

How can mindfulness connect us more to our bodies?

The body is a powerful tool that most of us are not using to its fullest potential. Mindfulness can improve the connection between your mind, body, and spirit. Cravings and emotions show up on the body before we are thinking about them. Most of us, however, are not aware of these body sensations, and realize we are triggered, craving, or emotional when it gets in our head and becomes harder to fight.

Spend some time thinking about what it feels like on your body when you have emotions, cravings, or triggers. You can train yourself to notice these sensations and then practice some mindfulness or relapse prevention before it becomes too difficult to talk yourself out of how you are feeling.

There are many more benefits that come from incorporating a bit of mindfulness into your daily routine – and it can become a great tool for success in your recovery by helping improve your mental health. Keeping your mental health in check and reconnecting with your mind daily can help yield long-lasting, life-improving results.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The SMART Global Research Advisory Committee (GRAC) invites you to join the first annual SMART Recovery Research webinar series. These webinars are being offered at different times to accommodate the time zones of our diverse Global Research Network. Each webinar will feature members of the SMART GRAC providing an overview of SMART Recovery research to date, updates on the latest research and explore the future of research on SMART Recovery. They are free with registration.

Tuesday, February 15, 2022

11am London | 6am New York | 10pm Sydney

Speakers:

- Dr. Charlie Orton: An introduction to SMART Recovery in the United Kingdom

- Dr. Alison Beck: An overview and update of evidence for SMART Recovery

- Dr. John Kelly: Who uses SMART Recovery? Preliminary findings from a US longitudinal investigation of recovery and health

- Dr. Ed Day: The opportunities for SMART Recovery in the United Kingdom, in treatment and research.

Thursday, March 10, 2022

3pm New York | 8pm London | 7am Sydney

Speakers:

- Dr. John Kelly: Who uses SMART Recovery? Preliminary findings from a US longitudinal investigation of recovery and health.

- Dr. Tom Horvath: Future directions for SMART Recovery research.

- Dr. Alison Beck: An overview and update of evidence for SMART Recovery.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Yesterday’s post and the discussion around it brought up a lot of good questions. Among them was the question, does it really matter whether we call it a disease?

It prompted me to look at some old posts. I’ll share versions of a few of them in the coming days.

A few variations of this have been posted over the years.

How we define addiction determines which helpers and which systems own the problem. The opioid crisis has been moving into medicine (both addiction specific and general medicine), but also into public health, mental health, criminal justice, etc.

Of course, the categorically segregated addiction treatment system has had serious problems with ethics, stewardship, and quality. There’s also no doubt that these debates can turn into turf issues. However, it’s worth considering how a categorically segregated system emerged to determine what should be protected and what can be modified or discarded. How problem definition fits into that history is an important element.

Here are a few thoughts from Bill White on the topic from Slaying the Dragon and some Counselor articles:

On problem ownership:

Whether we define alcoholism as a sin, a crime, a disease, a social problem, or a product of economic deprivation determines whether this society assigns that problem to the care of the priest, police officer, doctor, addiction counselor, social worker, urban planner, or community activist. The model chosen will determine the fate of untold numbers of alcoholics and addicts and untold numbers of social institutions and professional careers.

The existence of a “treatment industry” and its “ownership” of the problem of addiction should not be taken for granted. Sweeping shifts in values and changes in the alignment of major social institutions might pass ownership of this problem to another group.

White, W. L. (1998). Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, page 338

On the segregation-integration pendulum:

American history is replete with failed efforts to integrate the care of alcoholics and addicts into other helping systems. These failed experiments are followed by efforts to move such care into a categorically segregated system that, once achieved, is followed with renewed proposals for service integration. After fighting 40 years to be born as an autonomous field of service, addiction treatment is once again in the throes of service-integration mania. This cynical evolution in the organization of addiction treatment services seems to be part of two broader pendulum swings in the broader culture, between specialization and generalization and between centralization and decentralization. Once we have destroyed most of the categorically segregated addiction treatment institutions in America, a grassroots movement will likely arise again to recreate them.

White, W. L. (1998). Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, page 333

On the historical essence of addiction counseling:

If AOD problems could be solved by physically unraveling the person-drug relationship, only physicians and nurses trained in the mechanics of detoxification would be needed to address these problems. If AOD problems were simply a symptom of untreated psychiatric illness, more psychiatrists, not addiction counselors would be needed. If these problems were only a reflection of grief, trauma, family disturbance, economic distress, or cultural oppression, we would need psychologists, social workers, vocational counselors, and social activists rather than addiction counselors. Historically, other professions conveyed to the addict that other problems were the source of addiction and their resolution was the pathway to recovery. Addiction counseling was built on the failure of this premise. The addiction counselor offered a distinctly different view: “All that you have been and will be flows from the problem of addiction and how you respond or fail to respond to it.”

Addiction counseling as a profession rests on the proposition that AOD problems reach a point of self-contained independence from their initiating roots and that direct knowledge of addiction, its specialized treatment, and the processes of long-term recovery provide the most viable instrument for healing and wholeness. If these core understandings are ever lost, the essence of addiction counseling will have died even if the title and its institutional trappings survive. We must be cautious in our emulation of other helping professions. We must not forget that the failure of these professions to adequately understand and treat addiction constituted the germinating soil of addiction counseling as a specialized profession.

White, W. (2004). The historical essence of addiction counseling. Counselor, 5(3), 43-48

On the risks of diffusion and diversion:

Diffusion and diversion constitute two of the most pervasive threats in the history of addiction treatment institutions and mutual-aid societies. Diffusion is the dissipation of an organization’s core values and identity, most often as a result of rapid expansion and diversification. Diffusion creates a porous organization (or field) that is vulnerable to corruption and consumption by people and institutions in its operating environment. Diversion occurs when an organization follows what appears to be an opportunity, only to discover in retrospect that this venture propelled the organization away from its primary mission.

The current absorption of addiction treatment into the broader identity of behavioral health is an example of a diffusion process that might replicate two earlier periods – the absorption of inebriate asylums into insane asylums and the integration of alcoholism and drug-abuse counseling into community mental health centers in the 1960s. This diffusion-by-integration has generally led to two undesirable consequences: 1) the erosion of core addiction treatment technologies; and 2) the diversion of financial and human resources earmarked to support addiction treatment into other problem arenas.

White, W. L. (1998). Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, page 341

The complexity of addiction requires an equally complex notion of recovery. Holistically, recovery is generally conceptualized across three classes of variables- individual, social, and ecological. The biopsychosocial model of recovery fits well within this framework. Expanding recovery conceptually to include the environmental sphere of variables has allowed for new contextual and structural factors to be incorporated into the study of recovery trajectories. This has been the recent scientific trend. However, itemization of recovery factors across all three classes is ultimately incomplete without establishing what binds these variables together. This article proposes the relational nature of recovery as the theoretical connective tissue which binds together these multidimensional variables across individual, social, and ecological spheres.

Introduction

The working definition from the Recovery Science Research Collaborative (RSRC) states that recovery is an “intentional, dynamic, and relational process” focused on improving wellness (Ashford et al., 2018). The RSRC definition is a synthetic and consensual definition drawn from the leading definitions of the time to operationalize the notion of recovery for recovery scientists to use. As such, this definition is a valuable starting point to theorize aspects of recovery.

The current evolution of recovery science presents an opportunity to consider what makes a recovery successful and how healing can emancipate individuals from destructive patterns and lifestyles. Along with new definitions, new theories allow more inductive ways to consider recovery outside of clinical, medical, and pathological frameworks. Recovery-Informed Theory states that “recovery is self-evident, and is a fundamentally emancipatory set of processes” (Brown and Ashford, 2019). Hearteningly, this theory has promoted an emphasis on personal experiences as a primary source for conceptualizing and studying recovery and has helped relieve researchers of the burden of imposing artificial constructs that are contextually absent of meaning, systems critique, and/or intrusive or destructive to recovery communities.

Since recovery predominantly occurs over the course of years within the daily lives of individuals and is not reliant upon persistent clinical or medical support, recovery constitutes both a lifestyle and a culture. As such, recovery is a social, relational, and identity process, whereby thriving becomes the best predictor of outcomes (Best, et al., 2016; Gutierrez et. al, 2020).

Theories and metrics such as Recovery Capital and the Strengths and Barriers in Recovery Survey (SABRs) denote several life areas that account for the significant variance of recovery success, stability, and progress (Best, et. al. 2020: 2021). The Brief Recovery Capital Scale captures personal and social recovery capital in a unipolar instrument (Vilsaint et al., 2019). The SABRs identify life areas, such as taking care of one’s health and engaging in meaningful activities, that are associated with recovery stability (Best et. al 2021). Criticism regarding the measure of recovery capital involves the ecological or community dimension (Hennesey, 2021). While the SABRs instrument better identifies specific factors that serve as recovery strengths and barriers, such as criminal justice involvement and access to transportation (Best, et al., 2021). However, both of these concepts are missing a critical relational component that needs to be further explored. The reason has to do with assumptions we make about recovery- namely, that intrapersonal, interpersonal, and ecological accounting of recovery supportive resources are as far as scientists can get toward measuring recovery. This of course relates to the idea of observable data and the limits of existing recovery measures.

However, I would argue that while personal strengths, access to resources, and community support are critical for recovery, it is really the individual’s relationship to these features that genuinely tie them to recovery. While the difference may seem slight, adding the relational nuance to our scientific models is critical to understanding why those with access to resources still may not recover, or how those with no access might recover anyway, and why systems seeking to support recovery must go further than simply providing necessary forms of support. In short, we are missing the ties that bind recovery supports together. Let’s take a common example – consider the fact that no matter how helpful one’s surroundings may be, without the desire to recover, little can be done to help a person who is struggling with addiction to get into recovery. This is because the individual and their relationship to their environment have not gone through the necessary shift required to make use of the available resources. Yet it is also unhelpful and potentially harmful to assume the person “just doesn’t want it bad enough” – Something more is needed here, we can bean count recovery resources all day long, but without understanding the relational dimension between the individual and those supports, we will never achieve any true predictive power, scientifically speaking.

The Relational Impairment of Addiction

Any family member who has dealt with a loved one deeply affected by addiction knows the challenges of supporting them. Several models and theories related to the challenges of supporting a loved one struggling with addiction exist, ranging from so-called “tough love” to strategies that use “unconditional positive regard”. While this article is not concerned with debating the pros and cons of various strategies, it is essential to note what is absent but implicit within these interventions- having a relationship with someone in active addiction can be painful, and at times, damaging to the emotional health of family, co-workers, partners, and friends. Furthermore, long-term recovery from addiction requires a re-articulation of relational space, namely developing boundaries, healing relational trauma, and learning new ways to interact with intimate others. At the same time, all the parties involved are ideally focused on the recovery process, both at the personal and relational levels. The need for sustained recovery focus and improvement is integral for the individual who is overcoming problematic substance use and for those concerned about them. Thus, a two-step process occurs, those dealing with a loved one in recovery must heal, alongside, and in cooperation with the individual. Often an entirely new relational format is needed within families, and sitting in on any family treatment session will illustrate. Obdurate and negative relational patterns constitute a huge clinical obstacle, one that requires a lot of ongoing work by everyone involved. Though our treatment systems have yet to fully adapt to healing the whole family, most clinicians understand and even stress the relational component of recovery. Obviously, recovery is not, and cannot be solely about the person overcoming addiction.

“Ideas, emotions, and attitudes which were once the guiding forces of the lives of these men are suddenly cast to one side, and a completely new set of conceptions and motives begin to dominate them” (Alcoholics Anonymous, pg. 27)

The relational aspect within families clues us into the importance of the relational space in recovery. From this, we can expand the idea. If healing the relationships within families is so vital to recovery, what about other relationships? What about one’s general relationship to the world, to society, economy, work, and education? We know these factors are important to recovery, but we have yet to frame the relational space beyond family and friends as equally important to understanding recovery. Addiction negatively impacts virtually all relationships. Not just relationships to people and to themselves. Is not healing one’s relationship to their intimate partner, equally important as healing one’s negative relationship to steady employment, or negative relationship to the Child Support Office, or a negative relationship to the bank and credit card companies? Are not the dysfunctional ties to these institutions and systems a cause for poor emotional health as well? What about when one looks in the mirror? Should they not use the same means of rearticulating their relationship with themselves as they do with their spouse.

The relationship to the self (intrapersonal), to others (interpersonal), and to their ecological field (ideas, institutions, systems, and society), must all be considered of equal importance. On the one hand, we can account for these three areas with certain metrics, but can we account for the relationship between the individual and each of these areas?

Not Just Human Relationships

What other relationships change in recovery? One of the most interesting effects of recovery involves changing relationships to ideas and institutions. One cannot underestimate how much ameliorative potential is unlocked in the re-articulation of the self in relation to the world through the recovery process. Often recovery requires that one let go of their existing views of various social institutions. Take for example a person who is involved with the law. In this case, one’s relationship with the criminal justice system is almost entirely negative. Often there is tremendous resentment towards police, judges, and probation officers. Existing criticism of the criminal justice system in America notwithstanding, if one is to live with an ounce of peace, then they quickly realize that toxic forms of anger aimed at anonymous systems, ideas, and institutions (as flawed as they may be), is a futile waste of precious emotional energy, and to continue to harbor deep senses of anger, hatred, and cynicism set one at an emotional disadvantage in their recovery. Or take a person’s negative relationships with institutions such as marriage, school, political parties, or employers. Regardless of whether one has a justified reason to consider these things in a negative sense, those in early recovery understand relatively quickly that their view of the world must change. This essential shift sets up a new relational possibility – the person comes to understand that rather than taking up the role of Sisyphus, refusing to be happy, or satisfied until such institutions radically change to alleviate their negative emotions, that they might simply reposition themselves either to a position of neutrality, or alternatively, acquiring the skills, knowledge, and capacities to honestly challenge such things down the road. This subtle repositioning often makes all the difference between a life lived in futile exasperation or one of proactive peace and wisdom. Even the Serenity Prayer is explicit on this point.

Relation to Resources, Rather than Resources Alone

So how might recovery researchers begin to capture these phenomena? First, to return to the general equation of recovery dynamics, we might see that it is not just a capture of variables from the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and ecological pools that matter in measuring recovery, but that it is the nature of those relations that should be the target. It is not just the resources of the self, it is the relationship to the self that matters. It is not just the number of recovery supportive social resources that counts, but it is the nature of one’s relations to other people, both near and far that matters. And finally, it is not just whether one is surrounded by helpful institutional resources for recovery, but rather, one’s relationship to these institutions that matter the most.

The New York Times published a guest essay this weekend challenging the disease model of addiction.

I’ve read several similar pieces over the years and frequently have the same experience. I agree with most of the writer’s points, but disagree with his conclusions.

Let’s walk through it.

Annual U.S. overdose deaths recently topped 100,000, a record for a single year, and that milestone demonstrates the tragic insufficiency of our current “addiction as disease” paradigm.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

The drug death rate is very troubling and discouraging. If we were to add deaths associated with tobacco and alcohol, it’s much worse.

This strikes me as evidence for the insufficiency of our interventions to prevent and treat addiction, and/or the insufficiency of our systems to deliver those interventions. It does not strike me as evidence that it is not a disease. If COVID, type 2 diabetes, or asthma are associated with a large death toll, is that evidence that they are not diseases?

Thinking of addiction as a disease might simply imply that medicine can help, but disease language also oversimplifies the story and leads to the view that medical science is the single best framework for understanding addiction. Addiction becomes an individual problem, reduced to the level of biology alone. This narrows the view of a complex problem that requires community support and healing.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

This portion starts to illuminate the disagreement between me and the writer.

He’s concerned that too many people believe biology and medicine are the only frames we need. Further, he’s troubled that this might lead to interventions that target only individuals and omit social interventions.

I share those concerns.

However, I don’t see this as reason to doubt the disease model.

I believe asthma is a disease and environmental interventions are important. In the case of asthma, climate change might be a reasonable target for intervention. I believe type 2 diabetes is a disease and community-level interventions are critical. COVID is a disease and individually targeted interventions are clearly an insufficient response. I also believe depression is a disease and interventions targeting social support will be essential for many patients.

I also believe that behavioral interventions are essential for responding to all of these diseases and many others.

My experiences and those of my patients seem more in line with how 16th- and 17th-century writers described addiction: a disordered choice, decisions gone awry.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

If we view addiction as a brain disease, I don’t see how disordered choice is incompatible. Choice occurs in the brain. One could argue that other diseases involving the brain (depression, bipolar, schizophrenia, OCD, etc.) also result in disordered choice.

[Benjamin Rush] was famous for describing habitual drunkenness as a chronic and relapsing disease. However, Rush argued medicine could help only in part; he recognized that social and economic policies were central to the problem.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

This is a better understanding. It might be worth asking how to restore and protect that broader understanding.

The author points to a history of using the disease model (or beliefs associated with the disease model) in ways that are racist. All of this history is true and important, but it doesn’t really say anything about whether addiction is a disease. COVID was racialized, particularly early in the pandemic, but this is not grounds for reclassification of COVID.

The author continues addressing social justice issues in responses to the drug problem and raises another important consideration:

Not all drug problems are problems of addiction, and drug problems are strongly influenced by health inequities and injustice, like a lack of access to meaningful work, unstable housing and outright oppression. The disease notion, however, obscures those facts and narrows our view to counterproductive criminal responses, like harsh prohibitionist crackdowns.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

I see how a narrow medical/biological framing of disease can obscure the roles of inequities, injustices, and oppression. I also see how blindness to those factors could lead to criminalization. However, a disease model, at worst, cuts both ways. A deterministic view may contribute to prohibition and criminalization, but a model that locates addiction, not in the drug, but in the interaction between the brains of certain users and the drug, might push in the other direction.

The important point he raises here is that “not all drug problems are problems of addiction”. To be sure, addiction constitutes a relatively small fraction of all drug problems. This is a critical point that, to me, reinforces the need to clarify the boundaries of addiction and distinguish it from other drug problems that are not a disease.

In contrast, today, descriptions of “brain disease” imply that people have no capacity for choice or self-control. This strategy is meant to evoke compassion, but it can backfire.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

No thoughtful expert would suggest that people with addiction have no capacity for choice or self-control. However, the author previously stated that a “disordered choice” model resonated with his experience, which fits well with the impaired control described in definitions of addiction that frame it as a disease.

The public responses that the chronic brain disease model evokes are complicated. (It may evoke less blame but more pessimism.) It seems to me that basing its designation on public reactions is the tail wagging the dog, and that unstable, conflicting messages probably contribute to pessimism and stigma. If that’s true, the best strategy is to just describe it accurately and focus on other targets for stigma reduction.

The author closes with reflections on the incompleteness of the disease model.

I am in full agreement that a narrow medical/biological disease model is incomplete, inadequate, and will lead us in the wrong direction with respect to prevention, treatment, and policy. The author is a physician and have a lot of respect for a professional that seems to be saying that his discipline can only hope to be a part of the solution to the problem.

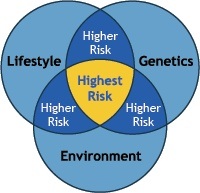

However, I don’t believe the problem here is that “disease” is the wrong category for addiction. The problem is that too many people think of disease in narrow medical/biological terms. This was addressed in the landmark 2000 article, Drug Dependence, a Chronic Medical Illness, which argued that drug dependence is comparable to type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and asthma when considering the roles of genetic heritability, personal choice, and environmental factors, as well the etiology and course of all of these disorders. Chronic diseases are generally complex in their etiology and in what’s required to effectively treat and manage them. The kinds of complexity present in addiction are more the norm for chronic diseases rather than the exception.

Recent years have seen increased interest in social determinants of health (SDOH), which serve the purpose of filling in the rest of the picture in terms of etiology and treatments/interventions.

Surprisingly, even genetic counseling offers insight into social and environmental factors that influence the onset and course of heritable illnesses.

So… is it misleading to call addiction a disease? Only if your understanding of disease is too narrow to allow for the complexity of chronic diseases and social determinants of health.

I think the solution is that we get better at talking about diseases and their complexity, rather than reclassify addiction because it’s too complex.

A study conducted in two rural Massachusetts jails found that people with opioid use disorder who were incarcerated and received a medication approved to treat opioid use disorder, known as buprenorphine, were less likely to face rearrest and reconviction after release than those who did not receive the medication. After adjusting the data to account for baseline characteristics such as prior history with the criminal justice system, the study revealed a 32% reduction in rates of probation violations, reincarcerations, or court charges when the facility offered buprenorphine to people in jail compared to when it did not. The findings were published in Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

The study was conducted by the Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (JCOIN), a program to increase high-quality care for people with opioid misuse and opioid use disorder in justice settings and funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health, through the Helping to End Addiction Long-term Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative.

“Studies like this provide much-needed evidence and momentum for jails and prisons to better enable the treatment, education, and support systems that individuals with an opioid use disorder need to help them recover and prevent reincarceration,” said Nora D. Volkow, M.D., NIDA Director. “Not offering treatment to people with opioid use disorder in jails and prisons can have devastating consequences, including a return to use and heighted risk of overdose and death after release.”

A growing body of evidence suggests that medications used to treat opioid use disorder, including buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone, hold great potential to improve outcomes among individuals after they’re released. However, offering these evidence-based treatments to people with opioid use disorder who pass through the justice system is not currently standard-of-care in U.S. jails and prisons, and most jails that do offer them are in large urban centers.

While previous studies have investigated the impact of buprenorphine provision on overdose rates, risk for infectious disease, and other health effects related to opioid use among people who are incarcerated, this study is one of the first to evaluate the impact specifically on recidivism, defined as additional probation violations, reincarcerations, or court charges. The researchers recognized an opportunity to assess this research gap when the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office and the Hampshire County House of Corrections, jails in two neighboring rural counties in Massachusetts, both began to offer buprenorphine to adults in jail, but at different times. Franklin County was one of the first rural jails in the nation to offer buprenorphine, in addition to naltrexone, beginning in February 2016. Hampshire County began providing buprenorphine in May 2019.

“There was sort of a ‘natural experiment’ where two rural county jails located within 23 miles of each other had very similar populations and different approaches to the same problem,” said study author Elizabeth Evans, Ph.D., of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. “Most people convicted of crimes carry out short-term sentences in jail, not prisons, so it was important for us to study our research question in jails.”

The researchers observed the outcomes of 469 adults, 197 individuals in Franklin County and 272 in Hampshire County, who were incarcerated and had opioid use disorder, and who exited one of the two participating jails between Jan. 1, 2015 and April 30, 2019. During this time, Franklin County jail began offering buprenorphine while the Hampshire County facility did not. Most observed individuals were male, white, and around 34 to 35 years old.

Using statistical models to analyze data from each jail’s electronic booking system, the researchers found that 48% of individuals from the Franklin County jail recidivated, compared to 63% of individuals in Hampshire County. As well, 36% of the people who were incarcerated in Franklin County faced new criminal charges in court, compared to 47% of people in Hampshire County. The rate of re-incarceration in the Franklin County group was 21%, compared to 39% in the Hampshire County group.

Additional analysis showed that decreases in charges related to property crimes appeared to have fueled the 32% reduction in overall recidivism.

The Massachusetts JCOIN project, led by Dr. Evans and senior author Peter Friedmann, M.D., of Baystate Health, is performing further research on medications for opioid use disorder in both urban and rural jails across more diverse populations, including women and people of color. The investigators are examining the comparative effectiveness of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for opioid use disorder in jail populations, and the challenges jails face in implementing them.

“A lot of data already show that offering medications for opioid use disorder to people in jail can prevent overdoses, withdrawal, and other adverse health outcomes after the individual is released,” said Dr. Friedmann. “Though this study was done with a small sample, the results show convincingly that on top of these positive health effects, providing these medications in jail can break the repressive cycle of arrest, reconviction, and reincarceration that occurs in the absence of adequate help and resources. That’s huge.”

The Helping to End Addiction Long-term Initiative and NIH HEAL Initiative, are registered service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Reference: E.A. Evans, et al. Recidivism and mortality after in-jail buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109254 (2022).

About the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA): NIDA is a component of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIDA supports most of the world’s research on the health aspects of drug use and addiction. The Institute carries out a large variety of programs to inform policy, improve practice, and advance addiction science. For more information about NIDA and its programs, visit www.nida.nih.gov.

About the NIH HEAL Initiative: The Helping to End Addiction Long-term Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative, is an aggressive, trans-NIH effort to speed scientific solutions to stem the national opioid public health crisis. Launched in April 2018, the initiative is focused on improving prevention and treatment strategies for opioid misuse and addiction and enhancing pain management. For more information, visit: https://heal.nih.gov.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health®

Dennis Irwin’s path to recovery has not been linear. He has had lapses, but has not given up. His love of the people in his SMART Recovery meetings keeps him motivated and wanting to be better.

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Abdul has been using SMART and other paths to recovery for several years. He appreciates the variety of people who attend SMART meetings and how inclusive it is to everyone. Abdul recently became a facilitator. Helping others has given him a new purpose in life.

Learn more about becoming a SMART volunteer

Find Abdul’s SMART Recovery meeting

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!