| Could your treatment court program benefit from a federal funding boost? Not sure how to make that happen? The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) is hosting two free webinars to help! |

| Funding Opportunities for Your Community in 2022: An Overview of What’s Ahead Wednesday, January 19 at 1:00 p.m. ET This webinar will help prospective applicants find funding opportunities that address their needs. In this webinar, attendees will learn the primary initiatives BJA plans to fund in 2022, along with eligibility requirements and estimated funding amounts. A Q&A session will follow at the end of the presentation. Register |

| The Funding Process: First Steps to Applying, How to Prepare Now, and Other Considerations Wednesday, January 26 at 1:00 p.m. ET In this webinar, attendees will learn what registrations are necessary to apply, how to navigate Grants.gov and JustGrants, and what resources are available for applicants, such as the Office of Justice Programs’ Funding Resource Center. A Q&A session will follow at the end of the presentation. Register |

The post Need Funding for Your Court? These Webinars Will Show You the Ropes appeared first on NADCP.org.

| Application deadline: Friday, January 28 |

| NADCP is now accepting applications for training from NADCP’s National Drug Court Institute on Standard IV of the Adult Drug Court Best Practice Standards: Incentives, Sanctions, and Therapeutic Adjustments (ISTA). Designed to provide knowledge and skills practice, the ISTA training will help treatment court teams coordinate an effective, research-based strategy and integrated response to participant behaviors and compliance. Over the course of two days, your team will receive instruction in the theory and application of behavior modification principles as they apply to an effective treatment court. This training includes a 90-day follow-up faculty coaching session to observe staff meetings and status hearings, and to provide feedback on progress with implementation plans developed during the training. 2022 available training dates: March 3-4 (Eastern) March 8-9 (Central) April 6-7 (Mountain) May 10-11 (Eastern) June 15-16 (Pacific) August 17-18 (Mountain) August 30-31 (Eastern) September 21-22 (Pacific) October 19-20 (Central) October 26-27 (Mountain) |

| This training is supported by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. |

The post Apply Now for Incentives, Sanctions, and Therapeutic Adjustments Training appeared first on NADCP.org.

Dr. Joe Gerstein is a Fellow of the American College of Physicians and Founder of SMART Recovery. He is also a retired Harvard University professor and lectures at addiction symposiums. Joe introduced SMART to the world and has facilitated over 3,000 meetings. His passion and motivation for helping others is still going strong after 50+ years. Joe shares some of his thoughts and perspectives for being and staying motivated in your recovery.

In this podcast, Joe talks about:

- How the addiction and recovery fields have changed in medicine through the years

- His focus on establishing meetings in correctional facilities

- The two components of motivation being a simple yet complex phenomenon

- The translation of desire to commitment

- Can you ever be cured of alcoholism

- Realizing that SMART was more than a two-point program

- The benefits of peers in recovery meetings

- How humans are a habit-forming breed

- The decisions that brought you to a meeting

- Three things to be successful in recovery

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Earlier this week, I had the opportunity to testify in front of the PA Senate Judiciary Committee in favor of legalizing Fentanyl Test Strips. One of the other testifiers, talked about the role of harm reduction in his own recovery process. Harm reduction was life saving for him. As he indicated in his testimony, his insurer would deny care to treat his severe substance use disorder beyond a handful of days. Of course, it did not work. Harm reduction kept him alive in between short treatment episodes. Our treatment system was resourced to fail him and to not deliver proper lengths of stays to get him into recovery or even engage him in ways that kept him involved. I know from prior public disclosures that it took him multiple experiences. He eventually got a longer duration and better intensity of care a few years later. Now he has a life, a family, and a role in healing his community, what we should want for all who have SUDs.

People seeking help within our SUD care system should probably get a disclaimer that we do not have an SUD care system managed to meet the long-term recovery needs of persons with SUDs. We don’t focus enough on helping people heal after we keep them alive, or even engaged with us over the long haul. It leads to a viscous cycle. While there has been some progress, our care systems most often fail those with more complex and severe SUDs. It has never really been resourced to provide people what they need to get better over the long term. Most of the time, we provide short duration care and move people through those services as quickly as we can in a conveyor belt fashion. We do a Hail Mary for each person as they pass through. The very need for expanding harm reduction strategies stems from the fact that we never actually properly invested in helping people recover. We should do that, too.

Back in 2013, my agency did a workforce survey, the Systems Under Stress Survey for our State Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs. That the statewide recovery community organization was charged with the roll of doing such a survey on how our systems served our community says a lot about how much we were valued at that time and how statewide recovery community organizations have a vital role to play in our system design, evaluation, and implementation.

We sent out surveys to the SUD counselors across Pennsylvania. We got over 1,000 back eventually, but the sample cut off was just over 800 respondents. Even in 2013, the SUD workforce was overburdened and not feeling like they had time to do the work to help people. They were stuck in piles of paperwork. We asked about goodness of fit between client needs and program capacity. Just under half of the respondents indicated that clients got lower levels of care than they thought as clinicians was needed and the people served needed more than they could offer given the resources they had. The funding mantra back then was you had to find ways to do more with less. The truth is when it comes to resources, you can only do less with less. Anecdotally listening to what the SUD workforce is saying right now, I suspect it has deteriorated even further since 2013. A number of these facets are on steroids in 2022.

My organization, PRO-A was the first RCO in the state of Pennsylvania to sign on to support increased harm reduction efforts. We did so even as we raised the need to invest more resources to keep people engaged with us and provide the care and support, they need to get well. Warm handsoffs help, but what happens next? We need harm reduction tools, but we also need a commiserate focus on what we do once we keep a person alive. We need to invest in keeping people engaged with us over the long term, particularly those with severe SUDs recovery. We should then help people flourish.

I am not the only person who thinks so. Senior editor for the Journal Alcohol & Drug Dependence Dr Eric Strain in a February 2019 Op-ed, noted that “our failure to forcefully advocate that patients need to flourish is tacitly acknowledged through interventions such as low threshold opioid programs, provision of naloxone with no follow up services, and buprenorphine providers who only offer a prescription for the medication.” He suggests that we need to engage patients to support flourishing and help support things that have meaning in their lives. We are not investing in flourishing as he so eloquently points out. Can you imagine what we could yield if we did?

While addiction is one of our costliest social challenges in resources and lives, we also know that 85% of the people who reach five years of addiction recovery remain in recovery for the rest of their lives. We should focus on long term recovery as our functional system metric for severe substance use disorders. Get people harm reduction services and help them identify what has meaning in their lives and support them in their recovery process. Provide the proper care and follow it up with recovery management services. Start measuring what works for whom so we can develop protocols for long term wellness for those of us with an SUD. If we invest in critically needed harm reduction services, but not in long term recovery infrastructure, we won’t even be close to the point in helping people thrive. Investing in recovery pays dividends in saved lives, restored families and healed communities.

We should steer in that direction.

A tweet from a colleague affected me this week. The subject was stigma in substance use disorders and he related how, at the funeral of a relative who had died very young from a heroin overdose, a family member callously slandered the dead man and skillfully ‘othered’ him. The message was ‘he was not at all like us’.

This technique of labelling, blaming, applying stereotypes and stripping those with substance use disorders of their humanity – their sameness to everyone else – might be an temporarily effective way of distancing oneself from the horror and pain of addiction and loss, but it is harmful to those struggling with substances, their families and, if truth be told, to the person using stigmatising language.

As a person with lived experience of substance use disorder and recovery, I’ve had my own share of stigmatisation. I’ve just written a book chapter about it. It diminishes you, discredits you and the discrimination that accompanies it has real-life effects. Often adding to self-stigmatisation, external forms of stigmatisation are pernicious and paralysing.

Two bits of research on stigma caught my eye recently. In the first[1], researchers compared public stigmatisation of those with alcohol use disorder with other mental health conditions.

They defined stigma ‘as a process in which people are firstly labelled and hereby assigned to an out-group, secondly subjected to stereotypes and prejudices, and thirdly exposed to discrimination and social distance.’

They found that ‘stigmatizing beliefs and behaviours toward people with alcohol use disorder were pervasive in the general population and usually more pronounced than toward persons with depression or schizophrenia.

More specifically, people with AUD tend to be perceived as more dangerous and more responsible for their condition, as well as being faced with a greater desire for social distance and a higher degree of acceptance of structural discrimination than people with substance-unrelated disorders.’

The findings threw up some challenges, as it’s all more complex than it seems. Framing alcohol use disorder as a mental illness seems to reduce the expression of anger in others, but increase the expression of fear.

The authors say: ‘If regarded as a stable and trait-like condition, related to assumptions on “bad character,” blame and feelings of anger might be less pronounced but fear and social exclusion nevertheless high.

Conversely, if regarded as a “bad behaviour”—that is, a state that needs to be overcome—moral judgments and blame of people with alcohol use disorder could be harsher, possibly leading to more discrimination and social exclusion.’

These dilemmas and seeming contradictions need more research, but what is clear is that those with alcohol use disorder are seen as more dangerous, more responsible for their condition and are more likely to experience distancing and discrimination than those with other mental health conditions.

The Norwegian research paper titled ‘Nothing to mourn, He was just a drug addict” – stigma towards people bereaved by drug-related death’[2] provoked the Twitter exchange I referred to above. If the first study appeals to the mind, then this is a study that goes straight to the heart and emotions. I felt angry and sad on reading it, but I’m glad I did. There are shared themes between the two.

Norway is producing a lot of impactful research at the moment. In this study, the researchers recruited 255 people who had lost a someone close to a drug-related death. Using both standardised and open-ended questions, they analysed person to person communications experienced by participants following bereavement.

Almost half of the participants ‘reported experiencing derogatory remarks from close/extended family and friends, work colleagues, neighbours, media/social media and professionals’. That’s right, when they were grieving, those closest to them made cruel, harsh comments when what they needed most was love, comfort and support.

The content of these remarks identified in the data was grouped into four themes:

- Dehumanising labelling

- Unspoken and implicit stigma

- Blaming the deceased

- The only and best outcome

I was told she was a fucking junky and a fucking whore who had not deserved to live. She should have been taken on the day she was born; she had no right to a life, and she used others’ tax money to get drugs, tricked men into giving her money by selling herself. Girls like that should die

Said about a woman’s 20 year-old daughter

More quotes:

It was a choice he made, so it was all his own fault

You are lucky to have been spared more anguish when he died

The death could not be such a big deal as he had never wanted to help himself.

Pretty heart-breaking.

One of the things that works best to tackle these kinds of attitudes is for those of us with lived experience to share our stories. Contact with those with lived experience has been shown to tackle stigma. The more that it can be seen that we are ordinary (actually, in terms of recovery – extraordinary) human beings, ‘the same as’ rather than ‘other’, the more we dissolve stigma, shame and discrimination. This is not always without risk though.

The researchers’ bottom line

Such communications were disgraceful and harsh, and contributed to marginalizing a group of grieving individuals who required support rather than being ostracised. Making people aware that stigma exists, increasing knowledge as to why it occurs and how it is transmitted in society can help remove the stigma

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

[1] Kilian, C., Manthey, J., Carr, S., Hanschmidt, F., Rehm, J., Speerforck, S. and Schomerus, G. (2021), Stigmatization of people with alcohol use disorders: An updated systematic review of population studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 45: 899-911. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.1459

[2] Kari Dyregrov & Lillian Bruland Selseng (2021) “Nothing to mourn, He was just a drug addict” – stigma towards people bereaved by drug-related death, Addiction Research & Theory, DOI: 10.1080/16066359.2021.1912327

Everyone looks forward to the New Year for many reasons – good food, quality time with friends and family – but many of us also eagerly await the holiday as an exciting way to hit reset on our lives and start fresh with a clean slate.

Everyone looks forward to the New Year for many reasons – good food, quality time with friends and family – but many of us also eagerly await the holiday as an exciting way to hit reset on our lives and start fresh with a clean slate.

For those in recovery, the New Year can be seen as an opportunity to set realistic goals for your recovery, keep yourself in check by following a specific timeline, and become the person you truly want to be, shedding the pain and bad memories from years past.

Setting goals for yourself, and then following through with achieving those goals, can be challenging and intimidating – but it can also be rewarding and life-changing. Here are four tips to get you on the right track to accomplishing your 2022 recovery goals.

Don’t be Afraid to Ask for Help and Support

Kick off the New Year by attending a meeting every day! Reach out to your sponsor, your friends, and your family whenever you’re struggling with your resolutions. Encourage friends and family to get involved with Al-Anon or Nar-Anon so they know how to best support you. With a team behind you willing to help and support your goals, there is nothing you can’t accomplish.

Invest Your Time in New Hobbies

Follow a classic New Year’s Resolution tradition and try your hand at new hobbies, activities, and skills. Fill your time with something you love to do that can help make you a better, more well-rounded person. Consider volunteering or other service work to give back to your community.

Don’t Be Too Hard on Yourself

As we said earlier, goals can be challenging and intimidating. Timelines and deadlines can help you make sense of your resolutions, but you cannot beat yourself up over little slip-ups or mistakes – it’ll just make you feel worse and less likely to end up accomplishing what you’re setting out to. Be realistic and self-assured. Turn to your support system when you’re experiencing doubt or hardships. Remember, one day at a time.

Create Measurable Goals

If you believe you can do it, you can. Having a plan with clear, concise, and measurable goals in front of you can give you the motivation you need when you’re struggling. You’ll be able to mark your progress and feel accomplished every step of the way. Being proud of what you’ve done will only serve to keep pushing you forward in your recovery journey.

Remember, no recovery journey is perfect. You may encounter slip-ups and moments of discouragement. However, by sticking to a plan with measurable, realistic goals, trying new and exciting things, and keeping your support systems close by, you can kick off 2022 assured that you’re doing everything in your power to make your journey successful. Happy New Year!

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

Reducing the stigma associated with addiction – the word itself now tagged with a degree of stigma – is a priority in drugs policy. Stigmatising attitudes contribute to drug harms and deaths through delaying access to treatment, leaving treatment early and increased risk-taking behaviour.

Brea Perry and her colleagues at Indiana University took a look[1] at the scale of the problem of stigma for non-medical prescription opioid use and dependence in a representative sample of over a thousand adults in the USA.

They used case scenarios to test out attitudes to opioid use and compared this condition to attitudes to depression, alcohol use disorder, schizophrenia and subclinical distress.

They found that the public were much more likely to label opioid use disorder a physical illness rather than a mental illness and that, compared to alcohol use disorder, it was less likely to be associated with ‘bad character’ and ‘poor upbringing’. However, there was a very strong tendency to want to socially exclude those with opioid use disorder.

They found evidence that the public ‘hold negative stereotypes about individuals after they have become dependent on opioids and may be pessimistic about their ability to function normally and successfully perform social roles’.

Taken together, our results suggest that public stigma and resulting discrimination will continue to profoundly shape the lives of people with OUD, adversely affecting physical and mental health and quality of life

So what are the solutions? Dr Perry and her colleagues said:

The most effective strategy for combating opioid use disorder stigma may be to avoid a rhetoric of hopelessness, and instead emphasize the recovery potential of affected individuals and communities

They suggest a reframe: ‘Along these lines, public health campaigns might focus on creating an image of persons with opiate use disorder as fighting against a serious condition with real prospect for remission, similar to cancer. Public attention could then be directed toward strengthening the formal and informal safety net required to support successful recovery.’

Commenting on this research[2], Patrick Corrigan, who researchers and writes on stigma in mental health and addictions, makes some pertinent points.

He says that unlike something like skin colour, there is no obvious mark associated with substance use disorder. Instead, “stigma is elicited by labels and labels occur by association: ‘Hey; that’s Mike coming out of the methadone clinic. He must be a druggie’. People with opiate use disorder or other substance use disorders will avoid stigmatizing labels by avoiding treatments associated with the label”.

He points out that unlike stigma in mental illness, the stigma of addiction is ‘socially, politically and/or legally sanctioned around the world’.

According to Corrigan, there are three agendas to be considered in order to erase the stigma.

- Service engagement agenda

- Rights agenda

- Self-worth agenda

In the last of the three, peer support by people in recovery is key in reducing shame which is created as a result of self-stigma. In all approaches though, Corrigan emphasises that people with lived experience of opiate use disorders must have central roles in development and implementation. In many addiction treatment and support settings this is already happening, although sometimes with hesitancy or resistance.

While the telling our own stories of addiction and recovery is not without risk, if done well our narratives have the power to humanise, to span chasms, to elicit empathy and connection and to tackle shame. When access to such experiences sits alongside formal treatment, the impact on retention in treatment and treatment outcomes is likely to be significant. As is the impact on stigma.

Personal histories can help with the reframing Perry and colleagues call for – to emphasise that those with opioid dependence can gain remission, just like those with cancer. Perhaps most importantly, the voice of lived experience can instil hope – something fundamental for recovery from the stigma and other harms of addiction.

Join the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

[1] Perry BL, Pescosolido BA, Krendl AC. The unique nature of public stigma toward non-medical prescription opioid use and dependence: a national study. Addiction. 2020 Dec;115(12):2317-2326. doi: 10.1111/add.15069. Epub 2020 Apr 20. PMID: 32219910.

[2] Corrigan PW. Commentary on Perry et al. (2020): Erasing the stigma of opioid use disorder. Addiction. 2020 Dec;115(12):2327-2328. doi: 10.1111/add.15145. Epub 2020 Jun 21. PMID: 32567106.

Switching from doctor to patient was not an easy transition for me. My first attempt at recovery was medically assisted, but only got me so far. What I needed was something more profound: hope, healing and connection to other recovering people. In this podcast for the National Wellbeing Hub, Dr Claire Fyvie interviews me about my own experience of addiction and recovery – warts, wonder and all.

Join me on Twitter @DocDavidM

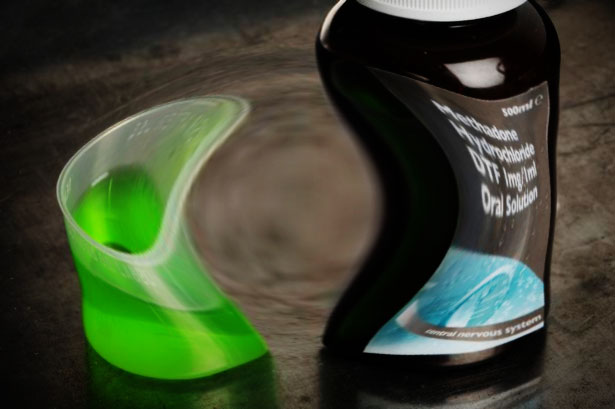

In a compelling study from Dublin, Paula Mayock and Shane Butler (Trinity College) make the point that little is known about the stigma experienced by individuals attending drug treatment services over prolonged periods. They explored this through the lived-experience narratives of 25 people prescribed long-term methadone. Their findings ‘reveal the intersection of stigma with age as profoundly shaping methadone patients’ perspectives on their lives’.

I like qualitative research because it is often affecting – stories bring to vibrant life important things we need to consider. You remember stories. You remember the feelings they engender. I connect with qualitative research in a way I never can with tables, graphs and statistics. I connected emotionally with this study.

In this study, 16 men and 9 women were interviewed. Two thirds were over the age of 40 and 16 of them had been on methadone for 20 years or more. Two were now long-term abstinent from all drugs including methadone. Nine people were attending a clinic for daily supervised consumption. Only three of the 20 were employed full-time.

The findings of this paper did not make for an easy read. You can sense something beyond detached academic curiosity here. Butler and Mayock reflect:

An intensity permeated these narratives in the sense that interviewees frequently – and, at times, emotionally – recounted treatment-specific experiences that engendered a sense of ‘otherness’ and shame.

Mayock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 2021

Methadone was seen as an instrument of punishment, ‘reflecting and amplifying’ public stereotypes around drug use and addiction:

It’s so demoralizing to go into the clinic and you’re just, you’re pissing [urinating] in bottles and grovelling to your doctor and grovelling to the chemists and that was your life, that was my life, you know.”

Rachel, service user

The research participants describe feeling ‘not normal’, having to ‘duck and dive’ and being treated ‘like dirt’. The absence of connection with the professionals they had contact with seems astonishing to me and the perception of being controlled or punished by the ‘techniques’ of treatment – e.g. threats of removal of takeaway doses for ‘dirty urines’ – was upsetting. Bad experiences reportedly extended to pharmacies where ‘public shaming’ took place.

The relationship with age and time on MMT (methadone maintenance treatment) was explored – there was a particular shame around being on methadone at an older age or for a longer period of time, such that individuals wanted to hide this, in a way that did not apply to other prescribed medications for other conditions.

The most harrowing theme in the paper is what Mayock and Butler call the private burden of stigma – the pernicious inner voices suffered by the participants, instilled powerfully and cemented down by years of reinforcement. The result is diminished spirit, low self-esteem and an erosion of humanity .

That’s what you do as a drug addict – you let people down, you’re unreliable, you’re of fucking no use to nobody.

Cormac, service user

The authors’ conclusion is hard hitting:

The lived experience of long- term MMT in Ireland is one characterized by relentless stigmatization, reflecting the marginal position of addiction treatment within the wider healthcare system and a failure to normalize methadone treatment.

Mayock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2021

It’s impossible not to have a strong reaction to this paper – it made me angry and sad and frustrated, but we do need to be a little careful here. The numbers are small, this is only one area of Ireland, and we are not hearing the other side of the story – how providers might see the situation and what limitations and duress they are working under, but that said, this is powerful stuff which merits consideration and further research.

So, what’s to be done?

The authors identify some issues specific to Ireland relating to the introduction of MMT which may be partly responsible, and they welcomed a policy shift away from criminal justice approaches towards a health approach, accepting that the tensions between the two are difficult to erase. They question the impact of a public campaign to tackle stigma, instead calling for organisational change in clinics and social structural change outside of treatment settings. Perhaps the most profound challenge they give us though is what we do with the upsetting legacy of what we’ve read in this paper.

I come back to a concern that bothers me here: the tension between what’s good for public health and what individuals want from treatment. The subjects in this research can’t have entered into treatment because they were seeking public health benefits from MMT – they would have wanted to see their lives getting better. The authors acknowledge this explicitly:

The well-documented public health benefits of MMT were not matched by a perceived improved quality of life among this study’s methadone patients

Mayock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2021

Mayock and Butler have looked at this in more depth in a separate paper (which I’m planning to come back to a different time) where people (the same ones I suspect) on MMT report being ‘passive recipients of a clinical regime that offered no opportunity to exercise agency’. This observation fits in with studies from elsewhere prompting the development of a large scale study looking into quality of life of those patients in treatment on MAT recently announced in the British Medical Journal.

While methadone and other examples of MAT have strongly evidenced benefits, medication does not offer meaningful healing for hurts. Methadone is not the problem here, nor is this only about stigmatisation. If we give methadone the blame we miss a trick.

I was struck by the absence of any focused interventions reported in the clinical settings where methadone was dispensed. Where was the compassionate approach to trauma? Where were the practical supports for housing, benefits, employment, families? Where were the mental and physical health interventions? Perhaps they were there but not reported, which says something in itself.

What would it have been like, I wonder, if the individuals had been offered significant support and interaction in each setting – primary care, clinic, pharmacy – by peers with lived experience? There is a call by the authors for involvement of stakeholder groups committed to harm reduction, but why not committed to harm reduction and recovery? Harm reduction is essential, but it’s not an end in itself. I have written recently about this quoting Eric Strain who talks about the importance of finding meaning and purpose and allowing people to ‘flourish’ in treatment.

So why not have peers on MAT, for instance, who had achieved their goals from treatment. Or peers who had moved on from MAT to abstinence? Or a mixture. What if clinics were perfused with hope and that hope was embodied in peer role models who had knowledge and experience of moving on and developing – of flourishing?

I have another concern. The word ‘recovery’ appears only twice in the text – once in a document title, and once as a point of tension where harm reduction approaches have to be defended from an attack by ‘the recovery model’. I might have picked this up wrongly, but the implication seems to be that recovery models are part of the problem, something I’ve also heard from some authorities here in Scotland.

The proposed solution – that stakeholders argue ‘overtly, explicitly and strongly for public support and acceptance of methadone as a legitimate and effective form of addiction treatment’ misses the point, in my view, that the prescription of methadone alone will never fulfil that goal, because it’s what goes alongside the prescription that brings positives into lives instead of simply reducing the harms.

I would argue that the introduction of recovery-oriented systems of care, (including medication-assisted recovery as an integrated component), rather than being a threat here, have the potential to transform the structures that have led to this degree of stigmatisation. The absence of hope in treatment systems is not only damaging to service users, but to those working in services. It’s easy to get burnt out. We need to set the bar high not just because we value those we work with, but because we also value ourselves.

I’ll leave you with something hopeful I quoted in a recent blog about stigma.

The most effective strategy for combating opioid use disorder stigma may be to avoid a rhetoric of hopelessness, and instead emphasize the recovery potential of affected individuals and communities.

Perry et al, Addiction, 2020

Continue the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

Paula Mayock & Shane Butler (2021): “I’m always hiding and ducking and diving”: the stigma of growing older on methadone, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, DOI: 10.1080/09687637.2021.1886253

As a GP in inner-city Glasgow in the 1990s, I looked after patients with heroin addiction. I got to know many of them well, I knew their families, I immunised their children and, distressingly, I saw some of them die. Because of the nature of general practice, I saw the dreadful impact of those deaths on their families and on their communities. Sadly, I saw few recover – in the sense of resolving their problems and moving on to achieve their goals. There was very little choice around treatment – though some wanted to attend the addiction clinic, many did not.

In the 2000s, our practice started a methadone clinic. It was called ‘shared care’ because they also attended the specialist service. Things got better for many and there was more of a sense of ‘doing something’. Apart from community detox (which was not infrequently requested), methadone was really the only choice on the menu. I am ashamed to say that my expectations were low. There was a feeling of ‘this is as good as it gets’. The idea of our patients accessing residential rehab wasn’t really in our minds and would have seemed fantastical.

Alcohol patients would sometimes be referred by us to a local inpatient unit, be detoxed and then come home with little, if any, community support. Return to drinking was the norm. Back in those days, I had never heard the term ‘mutual aid group’ and would not have rated such interventions in any case. I had two patients that I knew about who went to AA, so that did get on my radar, but back then it was generally a case of ‘doctor knows best’.

I certainly didn’t rate lived experience and while I listened to my patients and treated them with compassion, I can’t say there was any great element of us making decisions together. Looking back, I can see that there was a problem with my approach: it turned out this doctor who was making recommendations for treatment didn’t know much at all about addiction. My learning about addiction came about dramatically when addiction happened to me, but that’s a different story.

Fast forward a couple of decades and treatment is much better. The evidence base has grown, waiting times are said to be reduced and there is more choice. For those with opioid use disorder, we have methadone and buprenorphine. A newer, long-acting preparation of buprenorphine looks like, for some, it gives several advantages over tablets. We have much more widespread distribution of naloxone and a greater public awareness of addiction as a health issue. Several newspapers now support progressive policies to tackle Scotland’s appalling drug deaths in a way that would have been unimaginable in the 1990s.

The MAT (medicated assisted treatment) standards set a high standard for treatment access and for choice of medication and for how long to remain in treatment. Nowadays, the concept of partnership is embedded:

“Person centred care-planning that focuses on personal goals, with services working in genuine partnership with people, will result in more effective care and a better experience for people using services.”

MAT Standards, 2021

However, this issue of person-centred care with the patient as partner is an aspirational one that is hard to achieve. The MAT standards, not unreasonably given the evidence base, start from a position that choice is about which opioid to commence. The ability to choose something other than MAT in a way that identifies and manages risks, offers mitigations, and supports safer routes to reach one’s goals, is not outlined. While the principle is person-centred, the standards are fundamentally driven by public health concerns. Again, very reasonable given our public health crises in drug and alcohol deaths.

At a presentation on the MAT standards a couple of months back, intrigued by the notion of individual choice, I asked about exit routes from treatment, given that the standards emphasise that individuals should decide how long to stay in treatment. The answer was that individuals could ‘go back to their GP for prescribing’ when they wished to exit specialist services. I was disappointed by that answer. It wasn’t really what I had in mind and clearly wouldn’t remotely satisfy those who want to move to abstinent recovery.

In the work we’ve been doing on behalf of the Scottish Government in the Residential Rehabilitation Development Working Group it has become obvious that meaningful choice in treatment is limited in many parts of Scotland. This week a national newspaper drew attention to the plight of someone wanting to move on from MAT who was allegedly told there was no resource to do this. The Drugs Policy Minister stepped in to help.

It is certainly true from the evidence our group heard that access to residential rehab is not available to all and where it is available, the route to get there can be difficult to navigate. In terms of barriers, funding challenges and pathways are major issues, (if you are well-off, no problem) but so too are culture, attitude and the beliefs of individuals who may influence access.

It’s a fact that some people in MAT want to move onto abstinent recovery via residential treatment. However, residential treatment is mentioned only once in the MAT standards, and that’s to identify risk rather than advise on how such transitions can be managed safely as part of a comprehensive treatment system. Is there still an attitude of ‘professional knows best’ when it comes to treatment choices?

Choice and partnership in decision making are topical subjects. In JAMA this month, Yaara Zisman Llani and colleagues write in favour of Shared Decision Making (SDM)[1]. They outline the principles underpinning this approach:

- Eliminating power asymmetries between clinician and patient

- Acknowledging that there are at least 2 expert participants: a patient having lived experience expertise, a clinician having professional expertise, and sometimes a family member

- Eliciting patient preferences for their involvement in the decision making (autonomously, conjointly with clinician input, letting clinician make decisions) and eliciting the patient’s specific values that could guide the decision (eg, reducing medication adverse effects)

- Discussing at least 2 treatment options (eg, taking, tapering, or stopping antipsychotic medications)

- Making a decision that aligns with the patient’s goals, preferences, and values that also makes clear the risks involved in particular decisions

- Accepting that the patient’s choice of treatment plan may differ from the clinician’s recommendation.

The article addresses these goals as applied to psychiatry settings, but they are valid in addiction treatment and support too. How prevalent are power imbalances and how much weight is given to lived/living experience expertise? According to this research, Shared Decision Making is not happening much. The authors say this relates to clinicians’ beliefs that their patients are impaired and that this can be a form of stigmatisation, resulting in discrimination and ‘paternalistic decision-making’.

Their solutions are to introduce training on Shared Decision Making and create a level playing field with clinician and patient bringing expertise to the encounter where decisions around treatment are to be made. I think we can add to that by ensuring that clinicians are informed about all treatment options and understand them. Of course, the same should be true for our patients; we have a duty to explain the range of options.

If I examine my own practice, I think I am better at this than I used to be, though still have much to learn and relearn. I am much more aware of the authority that is afforded to me in my role and while I hold my own experience, beliefs, and biases, I am more mindful of how I need to find a shared space with the patient, while still being honest about the risks and mitigations. I do see patients who are impaired – particularly around lack of insight – creating challenges around how to navigate joint decision-making.

Decisions about treatment for opioid use disorder are not simple, but the principles around the making of those decisions ought to be. What is often missing when options are being considered is the need to make the link between what the patient and their family wants from treatment and the outcomes with which that particular treatment is associated, including those around quality of life. For instance, how often does rehab come up in discussions about treatment options? I’ve heard so many reports now about a desire to explore it being raised by individuals and their families, only for this to be dismissed by professionals. While this option may not be right for an individual at that time for a variety of reasons, it should be part of the discussion.

Another gap is almost certainly around how we introduce and effectively connect our clients to mutual aid and LEROs. (This is a real issue: the evidence base is strong and growing yet, when surveyed, less than 1% of service users in one Scottish city had ‘ever’ been to a mutual aid meeting.)

I have been, and still am, a proponent and prescriber of MAT, but I’m also a proponent of choice in treatment. If those of us who work in substance use disorder treatment keep the evidence base close (and seek to expand it beyond prescribing), understand the options, know how to mitigate the risks, and have shared decision-making at the heart of all we do, then those seeking our support and their families can only benefit from increased choice through joint decision making.

Continue the discussion: @DocDavidM

[1] Zisman-Ilani Y, Roth RM, Mistler LA. Time to Support Extensive Implementation of Shared Decision Making in Psychiatry. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021 Aug 18. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2247. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34406346.