When a person goes to prison, they are given derogatory labels, considered dysfunctional, and somehow seen as “less than” others in society. Often, they are ignored by the outside world and basically put out of mind. And even though the vast majority of these individuals return to society, little is done to prepare them for the challenges they will face. If they are struggling with a substance-use disorder, this lack of preparation can contribute to negative behaviors continuing.

For SMART Regional Coordinator Chuck Novak, the use of labels is counterproductive (consistent with SMART’s strong stance), and the lack of attention and preparation just doesn’t make sense. Besides facilitating meetings for SMART, he works at Reentry Resource Counseling in New Hampshire, using SMART Recovery tools and principles to counsel those he calls “returning citizens” (rather than ex-offender or similar label).

Novak himself was once a returning citizen, having served five years for behavior that stemmed in part from his own addiction and negative choices. When he was released, he was certain of one thing.

“I knew I needed to do a different job; I knew selling drugs was going to be out…I wanted a new life.“

He started college and chose to pursue a path where he could help others, specifically those who had been incarcerated. While he himself was behind bars he heard about SMART in passing, it was mentioned in a book about Rational Recovery and Albert Ellis, the founder of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

It made enough of an impression to choose to do a research paper for a college class. He titled his paper “Get SMART” and it turns out he was the one who has ended up getting professionally and personally gotten by SMART since then. Now he incorporates CBT and many other tools in his work with individuals who are reentering society. He has a passion for making sure SMART is well known, and a unique name for his strategy.

“I implemented something I called operation bed bug, [deciding that] everybody who came into the detox where I was working in Manchester New Hampshire was going to get “infested” with SMART Recovery, so in the detox program they were going to learn [SMART tools like] the hierarchy of value, cost-benefit analysis, disputing irrational beliefs, and then they were going to go off into other rehabs and they were going to tell the counselors about SMART”

Besides his colorfully named initiative, Novak credits other powerful resources, such as SMART’s InsideOut: A SMART Recovery Correctional Program®. He notes that InsideOut contextualizes “criminal thinking errors” which are an extension of irrational thinking. This aligns with the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ perspective, making his work in drug courts well received.

“At Reentry Resource Counseling we coordinate and offer services for the Federal drug court of New Hampshire. So, I do individual counseling, and I do another cognitive behavioral group specifically for the drug court.“

Novak also notes the value of SMART’s Successful Life Skills because it covers things like budgeting, anger management and other practical matters–not just stopping substance misuse. As a probation officer put it to him, it’s great that they aren’t doing drugs, but they now have to learn how to do life.

Currently, Novak makes presentations about SMART as often as he can, stressing that success comes from keeping your goals and values in the forefront of your mind. In this way, Novak says, participants can not only discover life beyond addiction, they can fully engage in it. Just like he has done for 20 years and counting.

Help Us Reach More Returning Citizens in Need

As demonstrated in Chuck’s story, the ripple effect of impacting one life impacts others. It is because of individuals like Chuck, who experience SMART and then decide to use their time, energy, and resources to spread its self-empowering messages, that we are able to reach more and more people who need support.

Unfortunately, there are communities – and returning citizens– across the country who still desperately need increased access to free, self-empowering, science-based mutual help groups. We are working to meet that need.

Your year-end gift to our Growth Fund will be put to work immediately, to help more people like Chuck and the participants in his meetings find the self-empowering recovery tools and peer support they need to overcome addiction and go on to live fulfilling and meaningful lives.

Additional Resources:

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

The percentage of adolescents reporting substance use decreased significantly in 2021, according to the latest results from the Monitoring the Future survey of substance use behaviors and related attitudes among eighth, 10th, and 12th graders in the United States. In line with continued long-term declines in the use of many illicit substances among adolescents previously reported by the Monitoring the Future survey, these findings represent the largest one-year decrease in overall illicit drug use reported since the survey began in 1975. The Monitoring the Future survey is conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health.

The 2021 survey reported significant decreases in use across many substances, including those most commonly used in adolescence – alcohol, marijuana, and vaped nicotine. The 2021 decrease in vaping for both marijuana and tobacco follows sharp increases in use between 2017 and 2019, which then leveled off in 2020. This year, the study surveyed students on their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study found that students across all age-groups reported moderate increases in feelings of boredom, anxiety, depression, loneliness, worry, difficulty sleeping, and other negative mental health indicators since the beginning of the pandemic.

“We have never seen such dramatic decreases in drug use among teens in just a one-year period. These data are unprecedented and highlight one unexpected potential consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused seismic shifts in the day-to-day lives of adolescents,” said Nora Volkow, M.D., NIDA director. “Moving forward, it will be crucial to identify the pivotal elements of this past year that contributed to decreased drug use – whether related to drug availability, family involvement, differences in peer pressure, or other factors – and harness them to inform future prevention efforts.”

The Monitoring the Future survey is given annually to students in eighth, 10th, and 12th grades who self-report their substance use behaviors over various time periods, such as past 30 days, past 12 months, and lifetime. The survey also documents students’ perception of harm, disapproval of use, and perceived availability of drugs. The survey results are released the same year the data are collected. From February through June 2021, the Monitoring the Future investigators collected 32,260 surveys from students enrolled across 319 public and private schools in the United States.

While the completed survey from 2021 represents about 75% of the sample size of a typical year’s data collection, the results were gathered from a broad geographic and representative sample, so the data were statistically weighted to provide national numbers. This year, 11.3% of the students who took the survey identified as African American, 16.7% as Hispanic, 5.0% as Asian, 0.9% as American Indian or Alaska Native, 13.8% as multiple, and 51.2% as white. All participating students took the survey via a web-based survey – either on tablets or on a computer – with 40% of respondents taking the survey in-person in school, and 60% taking the survey from home while they underwent virtual schooling.

This difference in location between survey respondents is a limitation of the survey, as students who took the survey at home may not have had the same privacy or may not have felt as comfortable truthfully reporting substance use as they would at school, when they are away from their parents. In addition, students with less engagement in school – a known risk factor for drug use – may have been less likely to participate in the survey, whether in-person or online. The Monitoring the Future investigators did see a slight drop in response rate across all age groups, indicating that a small segment of typical respondents may have been absent this year.

To address these limitations, the Monitoring the Future investigators conducted additional statistical analyses to confirm that the location differences for the survey, whether taken in-person in a classroom or at home, had little to no influence on the results.

“The Biden-Harris Administration is committed to using data and evidence to guide our prevention efforts so it is important to identify all the factors that may have led to this decrease in substance use to better inform prevention strategies moving forward,” said Dr. Rahul Gupta, Director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy. “The Administration is investing historic levels of funding for evidence-based prevention programs because delaying substance use until after adolescence significantly reduces the likelihood of developing a substance use disorder.”

The 2021 Monitoring the Future data tables highlighting the survey results are available online from the University of Michigan. Reported declines in the use of substances among teens include:

- Alcohol: The percentage of students who reported using alcohol within the past year decreased significantly for 10th and 12th grade students and remained stable for eighth graders.

- Eighth graders: 17.2% reported using alcohol in the past year in 2021, remaining steady compared to 20.5% in 2020 (not a statistically significant decrease)

- 10th graders: 28.5% reported using alcohol in the past year in 2021, a statistically significant decrease from 40.7% in 2020

- 12th graders: 46.5% reported using alcohol in the past year in 2021, a statistically significant decrease from 55.3% in 2020

- Marijuana: The percentage of students who reported using marijuana (in all forms, including smoking and vaping) within the past year decreased significantly for eighth, 10th, and 12th grade students.

- Eighth graders: 7.1% reported using marijuana in the past year in 2021, compared to 11.4% in 2020

- 10th graders: 17.3% reported using marijuana in the past year in 2021, compared to 28.0% in 2020

- 12th graders: 30.5% reported using marijuana in the past year in 2021, compared to 35.2% in 2020

- Vaping nicotine: Vaping continues to be the predominant method of nicotine consumption among young people, though the percentage of students who reported vaping nicotine within the past year decreased significantly for eighth, 10th, and 12th grade students.

- Eighth graders: 12.1% reported vaping nicotine in the past year in 2021, compared to 16.6% in 2020

- 10th graders: 19.5% reported vaping nicotine in the past year in 2021, compared to 30.7% in 2020

- 12th graders: 26.6% reported vaping nicotine in the past year in 2021, compared to 34.5% in 2020

- Any illicit drug, other than marijuana: The percentage of students who reported using any illicit drug (other than marijuana) within the past year decreased significantly for eighth, 10th, and 12th grade students.

- Eighth graders: 4.6% reported using any illicit drug (other than marijuana) in the past year in 2021, compared to 7.7% in 2020

- 10th graders: 5.1% reported using any illicit drug (other than marijuana) in the past year in 2021, compared to 8.6% in 2020

- 12th graders: 7.2% reported using any illicit drug (other than marijuana) in the past year in 2021, compared to 11.4% in 2020

- Significant declines in use were also reported across a wide range of drugs for many of the age cohorts, including for cocaine, hallucinogens, and nonmedical use of amphetamines, tranquilizers, and prescription opioids.

“In addition to looking at these significant one-year declines in substance use among young people, the real benefit of the Monitoring the Future survey is our unique ability to track changes over time, and over the course of history,” said Richard A. Miech, Ph.D., lead author of the paper and team lead of the Monitoring the Future study at the University of Michigan. “We knew that this year’s data would illuminate how the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted substance use among young people, and in the coming years, we will find out whether those impacts are long-lasting as we continue tracking the drug use patterns of these unique cohorts of adolescents.”

Earlier findings from a different NIDA-supported survey, conducted as part of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, showed that the overall rate of drug use among a younger cohort of people ages 10-14 remained relatively stable before and during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, researchers detected shifts in the drugs used, with alcohol use declining and use of nicotine products and misuse of prescription medications increasing. Adolescents who experienced pandemic-related severe stress, depression, or anxiety, or whose families experienced material hardship during the pandemic, or whose parents uses substances themselves were most likely to use them too.

In addition, a follow-up survey of 12th graders who participated in the 2020 Monitoring the Future study found that adolescent marijuana use and binge drinking did not significantly change during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite record decreases in the substances’ perceived availability. This survey was conducted between mid-July and mid-August 2020. It also found that nicotine vaping in high school seniors declined during the pandemic, along with declines in perceived availability of vaping devices at this time. These results challenge the idea that reducing adolescent use of drugs can be achieved solely by limiting their supply.

The Adolescent Brain Cognitive DevelopmentSM Study and ABCD Study® are service marks and registered trademarks, respectively, of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Guest blog by Tom Horvath, Ph.D.

The harm reduction approach to addressing addictive problems has until recently been highly controversial, at least in the U.S. Treatment and other change efforts in the U.S. have been primarily guided by the views that addiction is a disease and that the 12-steps are the primary (or only) method for change. Harm reduction accepts and encourages small steps toward change. The U.S. approach has typically required an immediate and large change, often involving a completely new perspective: “I’m an addict, I have a disease, I will abstain from everything forever.” The small steps approach of harm reduction, even though it describes how most human change occurs, has often been considered unacceptable and dangerous.

However, opiate overdose deaths have skyrocketed in recent years. It has been increasingly clear that the U.S. approach to supporting change is far too ineffective. Alternatively, the most effective approach to treating opiate use disorders involves using medications that parallel, to a significant degree, the effects of opiates. From an abstinence-only perspective these medications are unacceptable. But the number of deaths has been even more unacceptable to the public and governments at all levels. Traditional U.S. treatment is increasingly being over-ruled. For the first time, a U.S. president’s drug policy specifically mentions harm reduction as a primary principle.

Harm reduction involves a wide range of efforts and approaches. They support “any positive change.” Unlike the traditional prediction (that such changes provide a false hope of “real change”), harm reduction typically results in changes that are stable. Harm reduction is much more likely to place someone on a positive path and keep them there. When there is insistence that major change must happen immediately, the drop-out rates (or unwillingness to attend treatment at all) are substantial.

Undoing Drugs describes harmful ideas and methods that need to be “undone” in order for the U.S. to move forward with a harm reduction approach. In particular we need to update our understanding of “drugs.” In discussing one of the academic pioneers of harm reduction she writes:

[Alan] Marlatt knew that “undoing drugs” was essential to the mission: if alcohol isn’t seen as the drug that it is, its many users can easily dismiss “druggies” as some alien group whose experience is completely unlike their own. The spectrum of substance use must be seen in its entirety, so that we can recognize that it is indeed universal, across cultures and time (pg. 192).

As Szalavitz carefully documents, harm reduction got a substantial boost in the mid 1980s with the recognition that HIV and needle sharing went together. If an HIV user shares a needle with another drug user who also injects, the chances of transferring the infection are substantial. Of course, if we could persuade all drug users to stop using drugs, there would be no need for needle sharing. Also, of course, in any one moment we have not thus far been sufficiently successful with that kind of persuasive effort, and probably never will be.

Early harm reduction advocates focused on teaching drug users how to disinfect their needles, or better, provided them with clean needles, or even better, provided users clean needles and a safe place to inject (where medical staff were available in case of overdose). Each of these actions keeps users alive, setting up the possibility for change later. As some have said “dead addicts can’t recover.” The traditional treatment community, and many citizens and legislators, initially rejected this approach, preferring that drug users “hit bottom” even if it meant many of them died. The controversy was fierce, until the rise in opiate overdose deaths compelled us to seek new solutions.

Szalavitz documents the persistence of the individuals and organizations in the U.S. (supported by leaders in other countries) as they made the harm reduction activities available. Many got arrested or denounced. Many were themselves drug users who were able to change (as Szalavitz did, in the personal story she relates in the book). She states, “since I’d been spared, I wanted to learn everything I could about HIV prevention for IV drug users (pg. 31).” Many others were not so fortunate and died from overdose or HIV. For supporters of harm reduction this book provides the history, and the rationale, you might be only dimly acquainted with: “The history of harm reduction shows us that there is a better way—and it lies in undoing and dismantling all of our mistaken concepts about the nature of drugs and the people who take them (p. 12).”

Szalavitz has been a leading author and journalist about addiction, science, and public policy. She has diligently built her body of work and her career over three decades. In an interview I conducted with her (for the SMART Recovery National Conference, October, 2021; available on the SMART Recovery YouTube channel) she talks about these subjects in such depth and detail that it was clear she could probably dictate another book (it would be her 9th) in just a few days. Nevertheless, she conducted extensive research for this book specifically, including interviewing many of the leaders of the harm reduction movement. The harm reduction movement has been so massive that her book could present only U.S.-centric highlights: “Many additional specialized works need to be written, particularly to encompass the story of harm reduction outside of the United States and within specific communities (pg. xi).” To that end she is creating an archive of interviews and other material, soon to be available at www.maiasz.com.

This book has sections that focus on HIV and how it spurred harm reduction, leaders and activists, cities (e.g., New York, San Francisco), countries (e.g., the UK, the Netherlands), positive actions (like needle disinfection), legal issues and court cases, harm reduction definitions, public policy debates, racism (which is a major theme), overdose prevention, pain management, how to include drug users in decisions about them, housing for drug users, the problems with traditional treatment and “tough love,” the scientific evidence that supports harm reduction (that evidence is substantial), and where we need to go from here (in brief, to emulate Portugal, which has 20 years of substantial success with drug use decriminalization). Her focus on creating a sensible, equitable, and realistic future is crucial, because it would appear that we are not even halfway “there.”

If you have had any doubts about the value of harm reduction, this book is for you.

Other books by Maia Szalvaitz

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

In the most recent 10 years especially, I’ve been noticing some activity in our field concerning advancement of public health measures (e.g. cigarettes) and harm reduction strategies (e.g. opioids). Some of these efforts seem to include the notion that widespread harms would be reduced, and widespread health would be advanced, if use of drugs was:

- Culturally accepted

- Low cost

- Widely available

- Natural, not a tainted supply

- Low or lower potency

Backing up a bit, I’ll say this. I grew up in Southeast Asia and moved to the USA in the late 1970’s, just before my teenage years. I experienced culture shock upon moving to the USA, and have many, many stories about it that remain quite clear to me. Some of those stories pertain to drugs and drug use, but most of them pertain to the basics of everyday life.

In SE Asia, I saw the use of betel nut all the time. After moving to the USA, I never saw betel nut or the use of betel nut, ever again.

Effects of the use of betel nut (as quoted below) include: addiction, various cancers, neuronal injury, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmia, hepatotoxicity, asthma, obesity, type II diabetes, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, hypothyroidism, prostate hyperplasia, infertility, suppression of T-cell activity, and harmful fetal effects if used during pregnancy.

In Southeast Asia, betel nut has traditionally been low-cost, culturally accepted, widely available, natural and not from a tainted supply, and of low potency. And despite those factors, betel nut has long been a public health nightmare.

I often think of betel nut while I listen to arguments in favor of heroin that could be:

- low-cost

- widely available

- pharmaceutically pure

- culturally accepted, and

- not tainted with high potency but pure opioid additives like fentanyl.

I encourage the reader to read on through some recent findings below, and a question at the end.

Some Recent Findings

Garg, A., Chaturvedi, P. & Gupta, P. C. (2014). A Review of the Systemic Adverse Effects of Areca Nut or Betel Nut. Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. 35(1):3-9.

Areca nut is widely consumed by all ages groups in many parts of the world, especially south-east Asia.

There is substantial evidence for carcinogenicity of areca nut in cancers of the mouth and esophagus. Areca nut affects almost all organs of the human body, including the brain, heart, lungs, gastrointestinal tract and reproductive organs. It causes or aggravates pre-existing conditions such as neuronal injury, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, hepatotoxicity, asthma, central obesity, type II diabetes, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, etc. Areca nut affects the endocrine system, leading to hypothyroidism, prostate hyperplasia and infertility. It affects the immune system leading to suppression of T-cell activity and decreased release of cytokines. It has harmful effects on the fetus when used during pregnancy.

Little, M. A. & Papke, R. L. (2015). Betel, the Orphan Addiction. Journal of Addiction Research and Therapy. 6:e130. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000e130.

…there is virtually no public awareness or concern in Western nations about the fourth most widely used addictive substance, commonly known as “betel nut”, even though 300 to 600 million people worldwide are potentially addicted and at increased risk for oral disease and cancer. Of course, for much of the Western world, the ignorance and indifference to this widespread addiction can be attributed to what Douglas Adams identified in his Hitchhiker novels as the closest thing to invisibility, the SEP (somebody else’s problem) field. For thousands of years the use of areca nut (betel) has been endemic throughout South Asia and the Pacific Islands.

The main psychoactive ingredient of the areca nut is arecoline, which is known to be a muscarinic cholinergic agonist. Since arecoline is a weak base, another important ingredient in the betel quid that is required to alkalinize the saliva and permit absorption is some form of slaked lime, often from burnt sea shells or coral.

Historically, betel use cut through all levels of Asian society and was very common amongst the nobility.

The global health burden associated with areca use worldwide necessitates attention towards this addictive behavior. Given that it has been demonstrated that users do indeed become dependent, and that a substantial portion of the areca users have the desire to quit, it seems to be an addressable problem.

Papke, R. L., Hatsukami, D. K. & Herzog, T. A. (2020). Betel Quid, Health, and Addiction. Substance Use and Misuse. 55(9): 1528–1532. doi:10.1080/10826084.2019.1666147.

Areca addiction. Betel quid use (areca with or without tobacco) is an orphan addiction (Little and Papke, 2015), little studied and poorly understood. But there is an ever-growing appreciation for the global health impact of this form of drug addiction (Mehrtash et al., 2017; Niaz, et al., 2017). The majority of the betel quid users are stuck in a cycle of use and dependence while aware that they put their health at risk

Tungare, S. & Myers, A. L. (2021). Retail Availability and Characteristics of Addictive Areca Nut Products in a US Metropolis. Journal Of Psychoactive Drugs. 53(3):256-271. doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1860272.

In this field observational study, we found that areca products were relatively inexpensive, readily available, and easily purchased in grocery stores visited in Houston, TX.

Sumithrarachchi, S. R., Jayasinghe, R. & Warnakulasuriya, S. (2021). Betel Quid Addiction: A Review of Its Addiction Mechanisms and Pharmacological Management as an Emerging Modality for Habit Cessation. Substance Use and Misuse. 56(13):2017-2025.

Even though literature reveals a few cessation programs through behavioral support for (betel quid) addiction, its success has been limited in certain instances mainly due to addictive properties of (areca nut), resulting in withdrawal and relapse.

Consider the research side of the question.

I wonder if there would be interest in conducting a naturalistic study, with as many subjects as the size of a whole population, and carried out prospectively over thousands of years – to see if culturally accepted drug use, at low cost, with wide availability, natural and not from a tainted supply, and of low or lower potency, is sufficient?

Before we finalize our public health policy and harm reduction measures, we can study betel nut for lessons.

One of the reasons that I am so focused on our history as a recovery movement is that our past can tell us a great deal about the types of challenges we have faced, which strategies have been most successful, and the themes that occurred over time that influenced these processes. It helps us see our path forward.

The short version of our history is that everything in our entire SUD care system originated with the recovery community. Yet, those same systems then move away from the needs of the recovery community over time. We shift towards polices to punish people out of addiction. We put up care access barriers and expand administrative burdens as a direct result of our societies deep biases against persons who experience substance use disorders. Our best recovery community efforts then whither on the vine. A decade or two later, the recovery community rises again and rebuilds for the next cycle. Far too much energy gets lost as we are forced to reinvent the wheel each time.

As I spoke about recently in this piece, PAINFULLY OBVIOUS, there is deep discriminatory processes baked into our institutions. Partially by design. One of our authentic recovery community organizations (RCOs) compared what is being done with our current competitive grant process is that of a piece of meat being thrown into a pack of starving dogs and then watching them fight and hurt each other for basic sustenance. You can’t take grassroots community organizations who have never had stable funding and expect them to fight each other (and longer established treatment and other human service organizations) for a few dollars and expect to end up with a cohesive and inclusive care system.

One of the focuses of the new advocacy recovery movement was to nurture RCOs across America, in every community. It is a worthy vision. It starts with acknowledging that RCOs, run for and by people in recovery focused on supporting their own communities is valuable enough a resource to develop in its own right. Local organizations to support recovery in their communities and statewide recovery community organizations to provide technical assistance, training, and support. We are not there yet, not even close. This is in large part because we have set up a Conflict Model that pits communities who want to build community against each other to fight for table scraps of funding.

We are at a critical moment in history. Substance misuse is dramatically increasing in our society, in part as a result of the pandemic and a lot of underlying social strife and turmoil. Drug use is clearly shifting to multiple substance use patterns that make single substance treatment strategies less impactful for persons with severe substance use disorders. Our public SUD care system, underfunded and overburdened with demands and a decades long workforce crisis is crumbling even as we see more challenging times ahead. What we are doing is not working.

We are at that all hands-on deck; it takes the whole village moment. Our family members and neighbors are dying. It is a horrific process it is costing us vast treasures in lost lives and broken communities. Addiction and the consequences of it is the primary driver of human service and correctional costs in America. Yet, we pit our new, fledgling grassroots recovery community organizations against our established system of care and each other to sustain conflict. It is the antithesis of what is needed at this moment in time. We need the recovery set aside – a ten percent federal block grant for recovery, and then at the state levels, we must ensure such resources are allocated in ways that support the development of authentic RCOs instead of setting them up for conflict with each other and the rest of our care system.

We are in the early phases of a syndemic, with the addiction epidemic and the pandemic coming together in ways that will create a decade with even more challenge than we faced in the last decade. It is time to:

- Dedicate resources to developing Recovery Capital inside of our states and at the local and regional levels. Not in a competitive dog eat dog model, but one that honors and supports authentic recovery communities. Not divide and conquer nontransparent funding processes, but inclusive and recovery community oriented.

- Ensue that the recovery community is meaningfully engaged in how funding is allocated and what it builds – systems that embrace a recovery model, which understands and acknowledges that communities in recovery are the experts in what they need and how to build effective care models focused from the ground up, not from the top down.

- Use our SUD resources inside of our states instead of bringing in vendors from outside of the state to provide some training or technical assistance. We need to build recovery service and recovery community technical assistance capacity nested within recovery community organizations in every state, not send our monies elsewhere.

- We need to invest in long term recovery focused on the five-year recovery paradigm. We know that addiction is a long-term condition, yet all our models and research is all focused on narrow, short-term goals. It needs to change. We need to think bigger and build a care system that supports long term recovery.

- We need to take a hard look at discriminatory practices that set up barriers for persons in recovery from getting into and staying in our workforce. It is discrimination. Persons in recovery have always been the backbone of our SUD workforce. We need to create on ramps for persons in recovery to get into our field and then grow them.

We face a collapsing workforce and burgeoning needs on one hand and long term, recovery-oriented community building opportunities we are not using to even a fraction of their potential on the other. We know we will see a dramatic need for behavioral health needs created by the pandemic and social strife. We need to reinvent our systems to focus on strengthening grassroots community resources and expand recovery capacity across all of our communities, in partnership with those communities. We need to move beyond our low expectations for persons in recovery caused by discriminatory views about us and towards a long term recovery model.

What is true is that we know that 85% of persons with an SUD who reach five years of recovery stay in recovery for the rest of their lives – let’s build a system that focuses on these needs together. It has never been needed more than it is needed right now. Let’s move forward inclusively instead of starving our recovery community organizations of resources as we watch our friends and family members die. To sustain such a conflict-oriented model at this point must be called what it is, which is overt discrimination.

It is time for change, lives depend on it. We need to actually embrace recovery community organizations for what they are, one of the best options we have on the table to develop and support.

It takes a (recovery) village.

In a recent conversation, a colleague in the field told me they are attempting to “Catalog the biases at work among many of the scientific and medical experts in the field.” And they said to me, “I’d like to hear what biases you observe.”

This blog post serves as my attempt to respond to that request. What biases do you observe?

My current list of those biases is as follows:

- The idea that knowing the list of diagnostic criteria is the same as understanding the disorder

- Ignoring signs and symptoms of the illness that come from non-research sources

- Transforming each of the diagnostic criteria into a simple yes/no question

- Not including psychological struggles or improvements when determining remission

- Forgetting the complexity of real-world clinical implementation

- Conducting research with simple and compliant subjects, then doing clinical reasoning based on results of that work

- Understanding the illness by emphasizing the clinical discipline they were trained in

- Working to suppress symptoms and then conflating that with sufficient improvement

I’ll say more about each one of those in order, below.

Biases At Work

- In my experience, scientific experts in the field tend to use the criteria that are meant to be used to diagnose the presence of a substance use disorder as their main way of understanding the illness.

One trend inside the doing of that error is setting aside the phenomenological characteristics of addiction illness that are not found in the diagnostic criteria.

But people with addiction illness, those in recovery, and their family members – if they read over that diagnostic criteria list – would know that the simple list of diagnostic criteria falls far short of a sufficient quantitative and qualitative description of any one person’s addiction illness. Further, people who are maintaining recovery know all too well the signs and symptoms of their illness that are not found on the list of diagnostic criteria, and that tend to re-emerge at times over the years.

There are a variety of documented sources of that kind of information. My two favorite sources are older ones:

- The “Jellinek Chart” shows common signs of alcoholic disease progression.

- Gorski lists relapse warning signs that show up before going to back to using (during the early, middle, and later stages of regression out of recovery).

Both of those sources describe what it is like to have or to witness the illness. Lists like these can help someone understand addiction illness in its various forms and stages.

Here’s my favorite example of limiting one’s understanding of an illness to the list of its diagnostic signs and symptoms or objective research targets:

- Someone I know was present when a neurological bench scientist working in Parkinson’s research met a person with Parkinson’s for the first time. They were delighted to meet each other. But when the scientist explained what they were working on (movement problems, naturally) the person with Parkinson’s asked if they ever worked on gut motility. The person with Parkinson’s had to explain to the researcher that there are whole sets of problems not visible to others. The bench scientist was very grateful to hear of a whole new array of research targets – from a person who knew in a whole different way.

2. The bias listed as #1 above leads naturally into this next one. In my experience, empirical scientists/researchers are largely unaware of, or are quick to ignore or dismiss, objective signs that are universally accepted by clinicians and the people that experience the illness.

- But meanwhile, clinicians are expected by research scientists and medical experts to work with and not set aside the objective signs that are identified by researchers.

3. When they use the list of diagnostic criteria, they tend to turn each of the diagnostic criteria into a simple and straightforward question and ask the person if they ever experienced that or not. They generally do not first immerse themselves in the case history, then obtain information from data sources other than the person’s self-report, and last of all make a judgement from all the information gathered as compared to the diagnostic criteria.

4. In my experience they view the illness as being in remission if use of the substance stops or if the countable number of diagnostic criteria that are currently present shrinks to a small enough number.

- But quitting is diagnostic, not prognostic. And a simple elimination or reversal of the facts or information needed to identify the illness is not the same as the person healing or the same as full recovery. Or that the illness is not still in operation in other ways not listed in the diagnostic criteria.

5. In my experience research scientists or medical experts far from clinical work tend to make flawed assumptions (based on the logic of their training) about clinical implementation. For example, clinicians know we provide treatment based on practice guidelines. And clinicians tend to ask about adjusting the use of a guideline based on the facts or circumstances of the individual patient. And in my experience, most academics or researchers would answer such a question by saying something like, “Take a closer look at the guideline”. They believe most of the important individual differences from one patient to another are covered in the practice guideline for that disorder.

- But working clinicians know that patients have multiple disorders or divergent needs. And therapists might need to commonly use multiple practice guidelines simultaneously or have to attempt to blend them.

At that point, if that was explained to the research scientist or medical expert, their response would be to say something like, “Oh”, and the topic of the real world would be discussed.

6. Survivorship bias. Studies evaluate those that enter a study. They do not study those who can’t or won’t enter the study. And they study those that complete the study, not those that can’t or won’t complete the study. And studies only let in those who are healthy enough and uncomplicated enough to be studied in the first place (such as having only one disorder, and having no cognitive impairment, etc.).

- Should we only study the survivors of our protocol? Shouldn’t we also study the drop-outs, no-shows, and those that didn’t make it? Clinicians generally see complicated and ambivalent real-world patients in real-world clinical and community settings.

7. In my experience, their understanding comes right from their individual clinical discipline. They limit themselves to looking for things their specific tools are geared to find and tend to have little recognition of this as a self-limiting process.

- For example, physicians generally see addiction as a brain illness with bio-psycho-social manifestations. They do not tend to see addiction as a bio-psycho-social-spiritual illness.

In my experience this error becomes more rare or smaller when they are working as a member of a team. For example, when such a person is one member of a team (composed of staff from clinical psychology, primary health, nursing, spiritual care, addiction counseling, marital and family therapy, wellness/recreation therapy, and psychiatry) their information is added to that from the other disciplines, is contextualized, and in that way their understanding improves.

8. In my experience, they view improvement in a person as nothing more or less than suppressing symptoms (reducing the number or intensity of problem indicators). Working to suppress symptoms is the focus.

- They work toward obtaining statistically significant differences and lose focus on clinically significant differences.

- Working toward health and wellbeing is forgotten. That is to say, the focus is on the course of illness, not the course of recovery.

I’ll close with a quote to consider from Thomas Payte, MD:

The majority of the population prefer the certainty of illogical conviction to the uncertainty of logical doubt.

It seems to me this applies to all of us as people, including we professionals, and not to our patients only.

Recommended Reading

Haun, N., Hooper-Lane, C. & Safdar, N. (2016). Healthcare Personnel Attire and Devices as Fomites: A Systematic Review. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 37:1367–1373.

Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2005). Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. PLOS Medicine. 2(8): e124. 696-701. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

James L. (2016). Carl Jung and Alcoholics Anonymous: is a Theistic Psychopathology Feasible? Acta Psychopathol. 2:1.

Petrilli, C.M., Saint, S., Jennings, J.J., Caruso, A., Kuhn, L., Snyder, A., & 2 Vineet Chopra, V. (2018). Understanding Patient Preference for Physician Attire: A cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2017-021239.

Twerski, A. (1997). Addictive Thinking: Understanding Self-Deception. Hazelden.

Weiss, D., Tilin, F. & Morgan, M. (2018). The Interprofessional Health Care Team: Leadership and Development, Second Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA.

Research Describes Everyone and Applies to No One.

Dave Johnson is the Chief Executive Officer of the Fletcher Group, based in London, Kentucky. His background in social work, healthcare, and academia led him to starting Fletcher Group with the help of Ernie Fletcher, the former Governor of Kentucky. A recent grant connected them to SMART Recovery with the Rural Centers of Excellence Initiative.

In this podcast, Dave talks about:

- His journey from Big Sky country to the Motor City

- Flunking retirement after meeting Governor Ernie Fletcher

- Developing and operationalizing the Fletcher Group organization at record speed

- Being the catalysts for change

- Caring about the ones whom no one else does

- Receiving a HRSA grant for the Rural Centers for Excellence Initiative (RCOE)

- How and why recovery homes have gained public awareness in the last decade

- Connecting with SMART and implementing the curriculum and best practices into the houses

- Coaches and motivation

- The benefits for a recovery home participating in the RCOE program

- Gauging success: initiation, engagement, retention

- What recovery capital is and why it’s important

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

What happens when I relapse? 5 Signs to look for

For preventing a relapse, it is important to recognize warning signs before the actual relapse happens. Here are five signs to look for that may help you prevent a relapse:

- You get complacent. Sometimes when recovery is going well, you may get too comfortable in your new state of being and you make think, “I can handle it from here.” You must stay on track with working the steps or the inevitable backward slide begins. Don’t let success be your trigger!

- Your attitude and mood begin to change. Right before a relapse, you may act the way you did when you were using: selfishly. As a result, you’ve stopped helping others. Staying connected to others through service is important to recovery. Serving others helps you to maintain humility and keep your focus away from selfish desires.

- You think about “just one” that maybe just one drink or just one pill won’t hurt. Understand that ALL it takes is just one to get you back to the same place you were when you last quit drinking or using.

- You have the desire to contact your old using buddies. Before a relapse, you may think more about the folks you used to hang around and the things you did together during your substance abusing days. Reaching out to friends that are still interested in using will put your recovery in danger.

- You neglect to use your recovery tools. Avoiding relapse takes hard work and dedication. Continual use of your recovery tools will help you stay connected to your support.

If you are experiencing any of these warning signs of a potential relapse, remember to reach out for help. And if a relapse occurs, don’t allow your pride to keep you from getting back on track with your recovery. Call your sponsor, got to a meeting, work the steps.

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

There’s a narrative that’s been around for a while, but it’s been gaining ground in the last few months. This last couple of months alone, it’s been in the ether, permeating social media conversations and even appeared in an academic paper. The issue relates to recovery-oriented drug policies and the tone is negative.

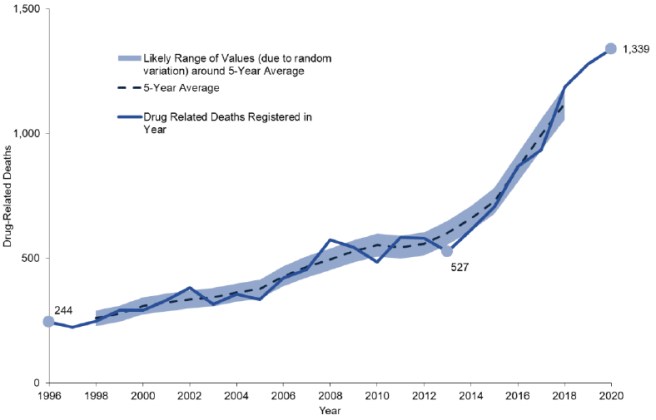

The thrust of this narrative? It’s that recovery-oriented drugs policies cause excess deaths. In the latest iteration I read that Scotland’s previous drug strategy (The Road to Recovery – which I’m going to call R2R) is to blame, or in less certain pronouncements, ‘may be to blame’ for Scotland’s high drug-related deaths. When you look for the evidence to back up such claims, it is hard, if not impossible, to find. So, are these claims fact or fiction?

In the 1980s the swing away from an abstinence aim of drug and alcohol treatment to harm reduction was largely driven by the developing harms associated with HIV. This was a welcome and necessary development, but by the early 2000s, it was beginning to seem to some that treatment options were limited and that we may have set the bar too low. When R2R was introduced, a readjustment took place. Did that readjustment cause harm?

In a recent paper[1], which I recommend you read, the focus is on benzodiazepines but there is a reference to drug policy more generally,. Colleagues write about changing drug markets in light of reductions in benzodiazepine prescribing:

“This may have been further exacerbated by a national drugs policy in 2008 based on achieving abstinence from all drugs. By discouraging agonist treatment a potential unintended consequence was that people who use drugs looked for supplements to diminishing prescriptions doses of methadone and buprenorphine.”

This paragraph has only one reference (to the R2R drugs strategy) but contains some significant statements which are presented as ‘potential’ facts. What are they?

- The national strategy was based on achieving abstinence from all drugs

- Agonist treatment was discouraged

- Prescriptions were reduced

- As a result, other substances were sought

It’s important to point out that my colleagues’ paper focuses on possible negative consequences from a reduction in benzodiazepine prescriptions ( R2R is not under the spotlight) so I’m picking up what appears to be a minor aside, but the underlying principle is one that deserves scrutiny. Is a recovery focus a dangerous focus?

Abstinence from all drugs?

The Road to Recovery was published in 2008. Drug-related deaths were on a gradually increasing trajectory before then. From the year of publication of R2R to 2010, drug related deaths actually declined before climbing gradually from 2010 to 2013 when they really took off, so it’s quite hard to link the policy directly to increasing drug deaths.

In any case, is it true that was R2R an abstinence-focussed policy? How many times, for instance, is abstinence mentioned in the text of its 96 pages? I’ve counted. It’s four. What are they?

- The first time abstinence is addressed in R2R is a historical reference to the policy response in the 1980s to both HIV and crime which led to a necessary movement away from abstinence to Scotland’s harm reduction focus.

- The second time (ironically) is to decry the artificial harm reduction vs abstinence divide and to point out the complimentary nature of these approaches.

- The third time is when it mentions the programme I work in, which was used (amongst others) as an example of how services can be broadened to offer choice – not instead of, but as well as.

- The fourth time is when it is pointed out that some achieve their recovery through abstinence and others through treatments which aim at stabilisation or reduction in use: hardly an abstinence-only ordinance.

So what is recovery?

Recovery in this strategy embraces reducing harm, reducing use, stabilisation, MAT and, yes, access to treatments associated with abstinence. At no point does the strategy call for reductions in access to OST – indeed it highlights and quotes papers underlining the primacy of this approach, calling for improved delivery of methadone (p22) and emphasising the role of GPs and pharmacists in providing substitute prescribing (p28-29). The Scottish Government ‘strongly’ supported the Orange Book Guidelines as ‘an authoritative guide’. The Orange Book promotes MAT as an evidence-based approach.

In R2R, recovery is not defined in terms of abstinence, but in terms of achieving personal goals, preventing relapse to illicit drugs, improving relationships, engaging in meaningful activities, building self-esteem, and building a home with family – the things patients consistently tell me (and I’m guessing, many other practitioners) that they want from treatment. When we conflate ‘recovery’ with ‘abstinence’ we get into this kind of muddle.

Harm reduction is often made an unnecessarily controversial issue, as if there were a contradiction between treatment and prevention on the one hand, and reducing the adverse health and social consequences of drug use on the other. This is a false dichotomy. They are complementary

United Nations 2008

It’s not that controversial

What’s in the R2R in terms of its focus on recovery is not new or even without consensus. The Reducing Harm, Promoting Recovery report of 2007, the Essential Care report of 2008 and the subsequent Independent Expert Review on Opioid Replacement Therapies in Scotland, commissioned by the then Chief Medical Officer, Sir Harry Burns, have similar themes and recommendations. They all agree on the prime importance of opioid substitution but point out that recovery is much more than a prescription and that Recovery Oriented Systems of Care (ROSC) are needed to help people achieve their goals. The current National Mission to reduce drug deaths is similarly broad and ambitious.

What the R2R strategy did was raise the bar beyond a prescription, explore goals and introduce the notion of individual choice. A bit like our current strategy. People deserve to be able to make informed choices. They deserve access to a range of evidence-based treatments.

Despite its benefits in reducing harms, some people do not want OST to be a forever thing. Some have moved on from OST and are in long term stable abstinent recovery. Every major review and policy paper that informed the R2R (and the current alcohol and drug strategy in Scotland) has extolled the benefits of OST but has also highlighted what is missing in our services.

It is not a criticism of OST to highlight areas where we need to do better. For instance, although OST is the fundamental treatment approach for those with opioid use disorders, if we think in terms of recovery/flourishing we actually don’t know much about whether it helps people achieve their life goals.

In R2R, nowhere is abstinence promoted over MAT – this idea is nowhere to be found in the referenced reports and reviews. Dr Brian Kidd the Chair of the Independent Expert Review despaired over the lack of ‘institutional memory’ in our structures and policies that have failed to see us take on board the lesson that MAT, while essential, is not the whole answer and that choice, opportunity, governance, data/evaluation, ROSCs, detox and rehab also need to be present.

Agonist (OST) treatment discouraged?

At the time of R2R I was working in an integrated system which encompassed harm reduction, MAT, detox, and abstinence. My colleagues working in specialist addiction services in the community absolutely did not discourage agonist treatment (opiate substitution); very much the opposite – it was and still is the primary focus of treatment for those with opioid use disorders.

I was teaching on the RCGP Certificate in the Management of Drug Misuse Part 2 course during this period. The course focussed on the evidence-base for OST and taught primary care practitioners how to embrace harm reduction and OST principles. The R2R was discussed, but we did not see it as a policy that promoted abstinence over OST. Yes, we also covered the concept of recovery, but not instead of OST. If prescriptions for OST were reduced as a direct result of R2R, I’d be interested to see that evidence;. Indeed, we were strongly encouraging GPs to prescribe.

Recovery is about helping an individual achieve their full potential – with the ultimate goal being what is important to the individual, rather than the means by which it is achieved.

Recovery policies and drug deaths

It is possible that by shifting the focus to person-centred outcomes, the R2R did impact negatively through local interpretations and practice, but unless there is evidence to back this up, this notion remains opinion. Similar claims were made during the work I was involved with when a committee of experts updated the UK ‘Orange Book’ National Clinical Guidelines on Drug Misuse and Dependence. On the 15th of September 2015 in London the working group heard evidence from Public Health England that they had studied the data on drug-related death data in England and explored whether these could be linked to ‘the recovery agenda’. They found no such link.

I don’t believe that the Road to Recovery was an abstinence-based strategy, nor that because of it, prescribers were under any pressure to reduce access to OST. I don’t think it’s accurate to describe the R2R as ‘based on achieving abstinence from all drugs’ (implying this includes MAT). I have not seen evidence that R2R contributed to our drug deaths crisis. What I have seen is a painful divide developing between harm reduction and recovery. When we repeat opinion and particularly when we package it as fact, this adds to the harm reduction good, abstinence bad narrative. This divide is turning into an ever deeper wound that needs healing, not poking.

The substance abuse field in both its research as well as treatment efforts is not giving due consideration to flourishing. We need to renew our efforts to give meaning and purpose to the lives of patients.

Eric Strain

There are lots of people in long term abstinent recovery from opioid use disorder in Scotland. Many of them acknowledge the lifesaving impacts of harm reduction interventions and MAT. There are plenty of people in recovery on MAT who have resolved their problems and are very happy to remain on medication. They are in recovery too.

Recovery journeys tend not to be linear; people may move between treatments and a particular status. Their needs and goals should be central to policy, as should measures to reduce harm. Our policies need to reflect the need for a variety of options and emphasise how important the elusive Recovery Oriented Systems of Care are in ensuring joined up approaches.

We should celebrate the gains individuals make in terms of recovery whether that’s through MAT or abstinence. I don’t think the R2R was a perfect drugs policy – none are – but it did encourage us to think bigger. I don’t believe it is or was partly responsible for our catastrophic drug deaths, though if we keep saying it often enough, I suppose eventually we will come to believe it.

Continue the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

Photo credit: https://www.istockphoto.com/portfolio/comicsans?mediatype=illustration (licensed)

[1] A McAuley, C Matheson, JR Robertson, From the clinic to the street: the changing role of benzodiazepines in the Scottish overdose epidemic, International Journal of Drug Policy, Volume 100, 2022