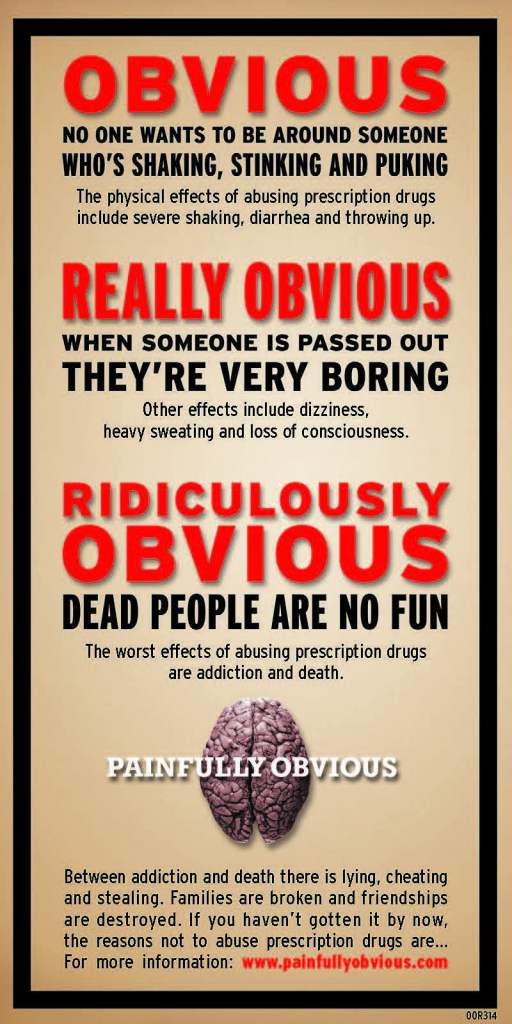

Painfully Obvious was the propaganda campaign that Purdue Pharma deployed to teach school children in America that addicted people are bad people. What is also painfully obvious is it is far too easy to influence Americans discriminatory and stigmatizing ideas that affirm existing biases. The graphic here is from Purdue Pharma’s “drug abuse prevention” media campaign. Part of a 4-million-dollar prescription drug awareness program to teach kids that addicted people are gross and experience things like “spastic shaking,” “projectile vomiting” and “explosive diarrhea.” I found this article about what they did, which of course was part of a larger campaign to sell oxycontin by fueling stigma and hammering “abusers” as noted by the Attorney General of the State of Massachusetts in their lawsuit against Purdue. Vile stuff.

Four million dollars to teach kids (who are now adults who most likely still hold these negative attitudes) to see addiction as shameful and that people who become addicted or die from addiction as stupid and weak. They were making over a Billion a year, so it cost them less than one day of earnings. As I recently articulated in my post about pseudo addiction and truthiness, they did it because it works. It is not hard to get people to believe that persons who become addicted are flawed humans, less than everyone else as our collaborative survey with Elevyst and RIWI shows is commonly perceived nationally.

What is also painfully obvious is that this discriminatory narrative is used in other ways to influence public policy. Tongue in cheek as it is, I hold that the First Law of Addiction Recovery funding is that that there is an inverse relationship between grassroots lived recovery community and the level of public funding across the states. The law also holds that the most money ends up with groups who are farthest removed from recovery. The less lived recovery experiences a group has, the more robust the funding. More marginalized communities add in additional dynamics of paucity of support. What other explanation can there be for why grassroots RCOs holds bake sales to buy printer cartridges and large academic groups and national foundations cash checks from our public well in the multimillion-dollar range? Discrimination plays out in terrible ways, and we need to talk openly about, fix it and make this ugly stuff ancient history. Purdue was blatantly discriminatory in its propaganda to sell oxycontin. Much of what is done now is often more subtle, yet with the same impact.

The entity that has done the most to support Recovery Community Organizations (RCOs) over the last 20 years in America is SAMHSA. They have been our key leader in respect to recovery support. SAMHSA has managed to keep a focus on recovery across multiple administrations. SAMHSA, look at what you helped us accomplish! We could not have done it without you. The evidence of what we can do is all around us, yet still quite fragile. The truth is that federal support has not translated to dependable funding for RCOs in the states. If you are one of those people in SAMHSA who helped move things in this direction, THANK YOU! But we need more than federal support. We need dedicated RCO funding in all 50 states. Discrimination in the form of implicit bias is the primary barrier to this goal.

Our RCOs contributions often become culturally misappropriated over time. Recovery community is not the dominant culture in the addiction service space. All it takes is to raise concerns about the ethics or mental capacity of recovering people. It is the very same dynamic of discriminatory practices and devaluing people who have used drugs that the Sackler’s deployed to sell their oxycontin. “Those people” are different, they are flawed, they deserve to be treated as less than others. “Those people” are ethically challenged, they need more training in a more regimented fashion than others. We cannot trust recovering people with money, they need extra oversight and smaller, if any allocations. This is the reason that funding that actually goes to authentic recovery groups is a rounding error in our federal allocations to the states.

When I talk with colleagues around the country, the story if quite similar state to state, with a few exceptions. If you are in state government and are working to change these dynamics thank you. There is a lot more to be done to fix this. It is not acceptable; it is quite simply discriminatory. In February of this year, a number of statewide RCOs sent a letter to Congress talking about the lack of funding and the need to increase the block grants to the state and to support statewide recovery community and other, regional authentic recovery community organizations. Our statewide gets not one penny of support from our Single State Authority (SSA). African American run RCOs seem to have it even worse than other RCOs. Here in PA, one of our original RCOs, a founding member of ARCO started and operated by the African American community closed shop forever because they could not get any public funding. No one in government lifted a finger to save it. It is gone now, forever. I know of another African American run RCO that gets zero public dollars and repeatedly gets passed by when they seek local or state support. What exactly is happening here?

If you work in a SSA, help us, you have unprecedented resources, use them to support us in meaningful ways. If you are a federal or state level legislator, start looking at this formally. Be part of the solution. We need you. You need us. We are all in this together. It is our community that is dying. It is our community that once in recovery becomes the vital element for healing for our families and for our communities. We are part of the solution, treat us as such instead of as a group to be tokenized on one hand and marginalized on the other.

These are common themes across the nation. It is discrimination, and we cannot end discrimination without openly acknowledging and addressing it as uncomfortable as such a process may be. Support the recovery set aside in front of Congress. Perhaps SAMHSA can put in place some specific requirements to the states that a percentage of dollars go to authentic RCOs run by and for persons in recovery from an SUD and have it monitored by our statewide RCOs. Not just organizations that add recovery to their name to take advantage of recovery as a brand. Not a process of go along to get along to get funded. If we need support in Congress to do so, let’s start building it. We have real value; we need to be funded as such. We should be treated as worthy partners and not pariahs. Given that opportunity and basic human respect, we deliver. History shows as much.

What is painfully obvious is that we need to change things, and that starts with openly talking about it and then actually changing it. “Behaving” got us here. It is time to stand up and speak out. If you are in government and reading this and it makes you upset or uncomfortable, it may be a sign that there is something to look at. Please do so and see us as allies in our own healing and not some token group to include on occasion when it benefits another agenda. That is unfair to us and marginalizes us when we are the vital link to supporting recovery for thousands of Americans. We should be in this together. We have to do this. Lives depend on it.

Article link HERE

SMART Recovery held its first annual Pathways to Recovery Virtual Walk in September. The event was enjoyed by many throughout the country. One of the participants, ChrisTLynne, shared her story on the pathway she took to walk for Life Beyond Addiction.

September 23, 2021 – Registration Closes

I logged into SMART Recovery today to pull up a tool before a meeting. This box popped up for the umpteenth time, but today, I chose to click on it. I thought, I’ve really enjoyed walking in or volunteering at 5Ks for causes I am passionate about (breast cancer walks, relay for life), and I missed it. What a great way to get some much-needed self-care in this weekend?!? So, I decided to register. It felt really good. Success of the day accomplished! Or as one of my favorite SMART volunteers would say, something to add to my Ta-Da list!

I decided to share this with a handful of people I love the most – my family and friends who are one in the same. I wasn’t looking for anything but emotional support on my recovery journey (just over 8 months free of my DOC). What I received was so much more! Their responses were very encouraging, motivating, and touching.

A few of them were supportive virtually, cheering me on from a distance across the country. And some of them wanted to walk beside me in support of my recovery journey. They know how important my recovery is (at this point acronyms like Hierarchy of Values (HOV) and Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) are dropped on the daily in my house) and they wanted to walk next to me on my Pathway(s) to Recovery Walk, pun intended. And to top it off, by the end of the day I was up to $75 in donations (an unexpected bonus!)

The very best part for me is that most of those who responded were what I call my Loved Ones (LOs), who have their own struggles with substance use disorders (SUDs). Without intending for it to, my self-care activity for the weekend turned into a sober-social event with my LOs (social distancing outside due to COVID of course). Something I have been looking for and craving for eight long months. The excitement of the day and anticipation of a great weekend ahead kept me up late that night… or maybe it was the coffee.

September 26, 2021 – Day of Event

Day of the walk. Alarm set, snoozed, dismissed… and I overslept. But I didn’t let that stop me. I was ready and in the car in less than 30 minutes and on the way to meet one of my favorite cousins at the park. The walk was amazing – just the right amount of exercise to be sore the next day, just the right amount of fresh air before my allergies acted up, and just the right amount of support and love to fill my heart.

After a nice, long shower I felt empowered and motivated to keep going the rest of the day – action really does precede motivation. I baked pumpkin bread before dinner (baking is one of my favorite Vital Absorbing Creative Interest (VACIs)), did a couple loads of laundry, and cleaned the house.

So that’s my story. I love that I chose the path we walked at the park today, just as much as the path I’ve chosen to recovery.

Take care of your self-care, y’all!

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Veterans Day | November 11, 2021

Today, Veterans Day, we pause to pay tribute to current and former service members of the United States armed forces. It is a day to recognize all those who answered the call to defend our country and its freedoms.

As John F. Kennedy stated, “As we express our gratitude, we must never forget that the highest appreciation is not to utter words, but to live by them.” Today, and every day, let us not only remember the sacrifice of those who have served, but honor them through acts of appreciation. No matter how you choose to mark the occasion, find a way to say “thank you” to some of the more than 18 million veterans in our country, and consider supporting one of the many organizations working to assist our veterans at home.

Sincerely,

Scott Tirocchi, M.A., M.S., L.P.C.

Major, U.S. Army (Retired)

Division Director, Justice For Vets

The post Veterans Day appeared first on NADCP.org.

The moral model of addiction is alive and well in the United States of America. Viewers of the Hulu series Dopesick learned something about this in episode four. It featured Purdue Pharma executive Dr. David Haddox. He is infamous now. He helped fabricate a condition called Pseudoaddiction. He did so to help Purdue Pharma sell oxycontin to people dying from addiction. I saw him at work up close and personal. I saw him selling these lies with my own eyes right here in Pennsylvania over five years ago.

Essentially, the concept is that if a person shows up in a doctor’s office presenting like they are addicted, they actually have undertreated pain and need more oxycontin, give them more oxycontin. Only drug addicts become addicted, normal people can’t get addicted, only morally flawed persons who decide to become addicted get addicted. This is vile and false, but of course it is accepted, it fits into the moral model that most Americans (including physicians) still have that “those people” are not like the rest of us.

This journal review on it noted that “Pseudoaddiction is a quarter-century-old concept that has not been empirically verified. Although no evidence supports its existence as a diagnosable clinical entity with objective signs and specific treatments, the term is widely accepted and proliferated in the medical literature as an “influential educational concept commonly used in pain management lectures” resulting from the “remarkable influence” of one case report.” A lie told once fitting a false narrative that people hold to be true is far more powerful than an uncomfortable fact told a thousand times. This is how human bias works.

Our societal discriminatory views on addiction were harnessed to make the Sackler family Billions of dollars (that they get to keep with immunity from future legal action) while the economic impact of what they did passed the Trillion dollar mark in 2017. They fed our biases and decimated our communities. We bought it hook line and sinker because of our own views that addiction is a moral flaw and not a medical condition. There is no way that what they did could have worked in a society that saw addiction as a legitimate medical condition to be concerned about. They leveraged America’s ignorance to make money.

I had a front row seat to see Dr J. David Haddox and his nefarious bag of tricks. We both served on a Pennsylvania state work group examining the impact of the opioid epidemic on the state of Pennsylvania. He usually sat directly across the room from me. He had a wardrobe that looked like it cost more than my car. His tailoring most likely did cost more than my car.

When we would suggest things like regular screening for addiction in general medical practitioner settings, he would say things like it was just one of many things a doctor could ask about but simply didn’t have time to do. He said it might make sense to ask every parent if their kids wear bicycle helmets, but doctors don’t have time to ask all those questions. He said this even as what his company peddled to those same children was addictive oxycontin. Prescribed to kids when they fell off those bikes and broke arms. Many of those same children later died of overdoses. If you ask how these former Purdue executives sleep at night, the answer is on the highest thread count Egyptian cotton sheets that money can buy.

I recall the unglamorous work of trying to press back against Haddox’s agenda. The claim that oxycontin was safe. The problem was that drug addicts were different from regular patients. Morally flawed people. Vile, false, and entirely believable in a society steeped in ignorance about addiction and recovery. As the report was in final preparation mode, I recall Haddox submitted a bunch of quotes and citations claiming that the addictive nature of oxycontin was overstated. I worked on this before my other duties in the early morning hours and at night after all the other tasks were done. I remember sitting in my living room chair looking at citations and quotes he had cherrypicked out of the journals to make it look like oxycontin was safe. My wife asking me when I would be done with work and me feeling guilty, she was a work widow as I toiled away against the clock and an army of corporate resources he had at his disposal. I would find his citations and discover that those same studies told a much different story on more careful examination. I tried my best to nullify his dirty work for Purdue Pharma. Outgunned as usual, but not defeated.

There is this thing called Hitchens Razor, coined by the late Christopher Hitchens. It holds that “what can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.” The body of evidence demonstrating that addiction is a medical condition with risk factors and treatments we should pay better attention is overwhelming. The sad truth is that Hitchens Razor is not what we use when we address addiction in the United States, the operant rule is closer to that of “truthiness” coined by Stephen Colbert. Truthiness is that which is not true, but which feels or sounds true without regard to the evidence.

Addiction and truthiness walk lock step in our society. We deal with addiction not from a basis of fact and objective science but from a position of ignorance, simply because we hold that drug addicts are not like other people, they are morally flawed. Truthiness in action.

We will not get anywhere we need to go without more fully addressing these deep societal biases we hold against addiction and those who experience it. People like the Sackler’s and Dr Haddox profit off of our destruction when we allow them to leverage our societal biases in this way. It must end. America needs to take a hard look in the mirror. “Those people are our people.”

One of things I am most excited to be involved with is a groundbreaking project examining stigma. One of our partners, RIWI who works with groups like the US State Department, the CDC and the World Health Organization just issued a press release on our collaborative work and a presentation we did at the fourth annual PRO-A Leadership Dinner. For the first time ever, we have an innovative data collection process that can be used to examine stigma and explore how to change public perceptions using granular data on what people believe in respect to addiction and measure it in near real time. This can inform data driven strategies to shift those perspectives and move America out of the moral model into a science driven view.

We need to get beyond truthiness and closer into the realm of Hitchens Razor. Many lives depend on it. I will continue to try to be part of the solution. Sitting on the sidelines while people die would be unbearable.

I hope you will do so too.

4 Healthy Habits To Help You Stay Clean & Sober

A big part of recovery is breaking the old habits that reinforced addiction and replacing them with healthy habits that support recovery. Some aspects of breaking these “bad habits” can be incredibly emotionally difficult, such as cutting ties with old friends that you drank or used with. Other habits can change by simply developing a new routine. Now that you’re clean and sober with healthier mind and body, you can start to focus on routine changes that will help you stay that way.

Diet & Exercise

Chances are that when you were drinking or using, you weren’t taking great care of your body; you probably didn’t eat well or exercise often. Luckily, these are two habits that are fairly easy to incorporate into your daily life. Set aside part of your week to plan your meals. You don’t have to adhere to a strict calorie count or a crazy restrictive fad diet, but you can make planning and eating a part of your routine. Food is fuel for body, so eat nutritious, but eat what you like. Employ the same mindset when it comes to exercise. Do what you like and what will fits in your life. You don’t have to become a marathon runner or an Olympic power lifter. You’ll reap benefits from even just a daily walk around the block or a couple of days a week weight training at the gym.

Healthful Sleep

Develop a healthy bedtime routine. Decide on a reasonable time to go to bed and a reasonable time to wake up. Start to wind down—turn off ALL electronic devices (mobile phone, tablet, computer, TV, radio)—at least an hour before your bedtime. The blue light emitted from electronic screens suppresses melatonin and makes it harder to fall asleep. In addition, the constant stimulus makes it harder for you to relax. Incorporate small tasks, like setting the coffee maker or making your lunch for the next day, into your nighttime routine that will make your morning routine easier. Make a cup of hot tea and spend a few minutes journaling or reflecting in your day. Allow your mind to settle down and relax so that you can sleep more restfully.

Get Interested

In anything. Maybe you’ve always wanted to try your hand at calligraphy or knitting. Maybe you really do want to become a marathon runner. Maybe you absolutely love to cook and want to develop seven-course meals for every dinner. Go for it. Find that thing that fills the space in your life that used to be taken up by drugs and alcohol. If there’s no particular skill or activity that interests you, try volunteering. Perhaps the thing that fulfills you most is giving back. Whatever you choose, build these activities into your weekly routine. If you make space for them, they’re more likely to become part of your lifestyle rather than imposition.

Go To Meetings

Perhaps it goes without saying, but go to meetings. In addition to exercise, diet, and sleep, you need solid emotional support as well. Meetings can start to fill the social void left when you stopped drinking and using. And luckily, meetings are pretty easy to incorporate into your schedule. They only last an hour, there’s at the very least one in your community every day, and more than likely several a day and at varying times.

It takes time to create and establish new habits, and some are going to be harder than others. Allow yourself room to feel things out and tweak if necessary. No novel ever went to the publisher at first draft. Give yourself grace while you establish your new routine. Remember, you’ve already kicked the hardest habit there is, the rest is a piece of cake in comparison.

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

Far too often, shame and stigma fuel addiction and prevent treatment, argues Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. But replacing judgment with compassion can save lives.

When I was six years old, as I was having dinner with my mother and three sisters, my mother received a telegram. She broke down crying as she read it. Her father — my grandfather — had died. In her grief, she locked herself in her room and would not let me console her. The memory of my inability to relieve my mother’s suffering still haunts me.

My sisters and I were led to believe that our grandfather had died of a heart attack. It was only decades later, when I had already been an addiction researcher for several years and my mother was herself dying, that she revealed the truth: My grandfather had had an alcohol addiction. Unable to stop drinking, he had taken his own life in a final moment of futility and shame.

Overwhelmed by this revelation, I asked my mother, “Why didn’t you tell me until now?” Her response was that she did not want me to lose respect for him or love him less.

My mother knew that I had devoted my life to understanding the neurobiological effects of chronic substance use. She had seen me speak about addiction as a disease of the brain and not a character defect. Of all people, I was someone she should have been able to speak to openly about why and how her father died. Yet, for her, the stigma of addiction and suicide was more powerful than the scientific understanding I was trying to bring to medicine.

Things have not changed much since that day. As a society, we still keep addiction in the shadows, regarding it as something shameful, reflecting lack of character, weakness of will, or even conscious wrongdoing, not a medical issue warranting compassionate medical care. Unfortunately, many in the medical profession harbor this mindset.

In fact, stigma remains one of the biggest obstacles to confronting America’s current drug crisis.

Last year alone, more than 96,000 people in the United States died from overdoses — usually from opioids but also increasingly from stimulants — and the pandemic worsened an already dire public health crisis. If you have not lost a family member or friend to drug or alcohol addiction or its consequences, which include diseases like cancer, you likely know someone whose family has suffered such a loss. Additionally, untreated substance use exacerbates many other health conditions or interferes with their treatment.

The direct and indirect health effects of drug and alcohol addiction are so numerous and devastating that they are considered root causes of the declining life expectancy in our country.

What the Science Tells Us

Science has shed much light on addiction. We now understand that changes in brain networks needed for self-regulation cause substance use to become compulsive in some individuals — despite their best efforts to decrease or stop use. We are also gaining an understanding of the genetic, developmental, and environmental factors that cause susceptibility to drug experimentation and to the brain changes underlying addiction.

For instance, data from a large longitudinal study of adolescents funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse in close partnership with other National Institutes of Health entities have provided insights into the adverse effects of poverty and adversity on the developing brain, including neurobiological changes that make drug use and addiction more likely.

On the positive side, prevention research shows that providing targeted interventions to families with low incomes or lacking social supports can avert — or even reverse — these neurobiological changes. What's more, decades of research on brain signaling systems have demonstrated that even once addiction takes hold, it is still reversible and recovery is achievable.

Unfortunately, stigma limits the impact of this knowledge and the reach of our tools.

The Role of Stigma

Stigma pervades medicine, policy, and communities.

Medical schools until recently offered little or no training in screening for or treating substance use disorders because, for many years, addiction was not seen as a medical problem. Even now, when medical systems offer treatment, it may be limited or inadequate. Among dedicated addiction treatment programs, fewer than half offer medications, which is tantamount to denial of appropriate medical care, according to a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report.

Insurers are often reluctant to cover addiction treatment, including medications for opioid use disorder, and coverage is limited when it is provided. Inadequate coverage puts these life-saving treatments out of reach for many people who need them. Stigma also prevents the use of medications in most justice settings — even though at least half of incarcerated individuals in the United States have a substance use disorder, often an opioid use disorder.

What’s more, many communities fail to provide harm-reduction measures, such as syringe services programs and the overdose medication naloxone, out of a moralistic — as well as factually incorrect — belief that those measures encourage illegal drug use.

Even when treatments and other supports are available, people with addiction may not seek them, fearing the judgments of those around them and the discrimination they routinely experience in the health care system. Patients are often hesitant to disclose their substance use to their physicians.

This contributes to the tragic reality that fewer than 13% of people with an illicit drug use disorder received any treatment for their addiction in 2019 and just 18% of people with opioid use disorder received one of the three safe, effective, and potentially lifesaving medications that could facilitate their recovery. The proportion of people with alcohol addiction who received medications is even lower: 3%.

Government policies, including criminal justice measures, often reflect — and contribute to — stigma. When we penalize people who use drugs because of an addiction, we suggest that their use is a character flaw rather than a medical condition. And when we incarcerate addicted individuals, we decrease their access to treatment and exacerbate the personal and societal consequences of their substance use. What’s more, drug laws are disproportionately leveraged against Black people and Black communities, driving societal and health disparities.

The aura of illegality affects the treatment of people with addiction. For example, some treatment programs expel patients for positive urine samples, as if relapse were not simply a known symptom of the disorder and a clinical signal to adjust the treatment approach but instead actual wrongdoing.

Prescribers of addiction medications are themselves monitored and subjected to strong limitations that don’t apply to other medications — or even to the same medications in different circumstances, such as prescribing buprenorphine for pain. Such oversight tacitly signals that there is something suspect about these treatments and the people who receive them.

Help and Healing

Stigma’s damaging effects go well beyond impeding care and care-seeking. Painful social and emotional effects like rejection, isolation, and shame — internalized stigma — drive drug-taking to alleviate one’s suffering, leading to a vicious cycle. It was internalized stigma that led my grandfather to end his life.

Research supports the lesson I learned firsthand in my own family — that stigma is not alleviated solely by educating people on the science of a disease. Partly, it requires facilitating contact between a stigmatized group and the wider community. If people with substance use disorders can share their experiences, then empathy and compassion can begin to replace judgment and fear.

For that to happen, addressing stigma must be a central prong of our public health efforts. If we’re going to end the current addiction and overdose crisis, we must treat combating stigma as no less important than developing and implementing new prevention and treatment tools.

We need a large-scale social intervention to change public attitudes toward addiction and people who have the disease. Besides ensuring proper training and the resources needed to help patients with substance use disorders, we need to seriously reconsider policies — not only laws but regulations and practices in health care and other settings — that promote viewing substance use as wrongdoing. And we must make it safe for patients and families to discuss addiction and remove the shame that interferes with its treatment.

Shop Using AmazonSmile and Advance Treatment Courts Nationwide

AmazonSmile donates 0.5% of eligible purchases to the organization of your choice—and now that includes NADCP! Funds raised through AmazonSmile will help NADCP provide more training and resources to the treatment court community.

Here’s how it works:

In order to support NADCP while shopping on Amazon, you must go through smile.amazon.com and/or have it set up on your Amazon app for NADCP to receive credit. Don’t worry, setup takes just a few minutes!

Here’s how to set up AmazonSmile on your computer:

On your computer, go to this link and click “Get Started.”

In the search bar, enter “NADCP” or “National Association of Drug Court Professionals.”

Hit “select” next to the National Association of Drug Court Professionals option.

Now that you’ve chosen your charity, you can go back to your AmazonSmile homepage, where you’ll see “Supporting: National Association of Drug Court Professionals” under the search bar.

Bookmark the link to make sure you are always shopping via AmazonSmile on your computer!

To make sure you’re supporting NADCP when you shop on your mobile device:

Open the Amazon app and click the menu button on the bottom right.

Choose “Gifting and Charity” and then “AmazonSmile.”

Click “Turn on AmazonSmile” and follow the easy prompts. Note: to keep AmazonSmile activated in the app, you must have notifications enabled.

Thank you for advancing justice with us!

The post Shop Using AmazonSmile and Advance Treatment Courts Nationwide appeared first on NADCP.org.

SMART Recovery is participating in a large research study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to collect data on a range of mutual-help alternatives for addiction, including SMART Recovery. The study, called the Peer Alternatives for Addiction 2 (PAL2) Study, builds on a prior study by the same team (PAL1) and involves study of diverse mutual-help group options—including SMART Recovery.

PAL2 data will be used to understand the specific aspects of mutual-help group participation that promote recovery. Data will also help us understand who benefits most from which group. The results will help addiction treatment providers to make informed referrals to mutual-help groups. They will also help people seeking peer support to make the best choices for their recovery pathways.

The study design involves online surveys with 800 people, including 200 from SMART Recovery. To obtain as many participants as possible, we encourage you to participate.

Study participants:

- U.S. residents only

- Must be 18+

- Have attended (or led) a meeting in the past 30 days

- Individuals surveyed for PAL1 may not participate in PAL2

- Will receive Amazon gift cards totaling up to $115

Click here to listen to Principal Investigator, Dr. Sarah Zemore, share her goals and the impact they want this study to make in the latest SMART podcast.

Please visit the study website and consider participating: www.pal2study.org.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Dr. Sarah Zemore is a Senior Scientist at the Alcohol Research Group in Emeryville, California, and the Principal Investigator of the Peer Alternatives for Addiction 2 (PAL2) Study. This is the second phase in the study which focuses on the benefits of mutual help groups in recovery.

In this podcast, Sarah talks about:

- Her background in social psychology, then becoming interested in the addiction recovery process

- Previous studies being too academic with little translation to the real world

- The power researchers have to shape services and make an impact

- The goals, challenges, and findings from the 2015 PAL1 Study

- How the new PAL2 study will provide a deeper understanding the benefits of mutual help groups

- The focus in PAL2 will be on specific subgroups and how participation is different, i.e., in-person versus online meetings

- Mechanisms of action and the key drivers of recovery

- Ways to participate in PAL2 study and how the data will be used to provide recommendations to treatment providers

- The importance of knowing the range of recovery program options available

- Welcoming feedback on the work and study

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Sam Quinones’ recent Atlantic article about methamphetamines came up recently in a conversation with a couple of friends recently.

I hadn’t read it, but one of the friends responded that it had elements of moral panic. This response was consistent with comments I had seen on Twitter.

My impression was that moral panic has been a serious problem in the history of social responses to alcohol and drug problems AND that many of the Twitter commenters were probably insufficiently concerned about the re-emergence of methamphetamines and stimulants as major drugs of misuse.

This provoked some questions for me:

- Is the problem the moral element? Or the panic element? Or both?

- What are the traits of a problem that make it hard to determine the right amount of concern?

- What is the right kind of concern (instead of moral panic) and what traits of problems make them vulnerable to the wrong kinds of concern?

Climate change came to mind as a problem with similar challenges.

I recently heard climate change described as a “hyperobject” by a journalist arguing that the current American political crisis has similar features.

Even now, I struggle to find the adequate word to describe the moment. It makes sense: our 21st century existence is characterized by the repeated confrontation with sprawling, complex, even existential problems without straightforward or easily achievable solutions. Theorist Timothy Morton calls the larger issues undergirding these problems “hyperobjects,” a concept so all-encompassing that it resists specific description. You could make a case that the current state of political polarization and our reality crisis falls into this category. Same for democratic backsliding and the concurrent rise of authoritarian regimes. We understand the contours of the problem, can even articulate and tweet frantically about them, yet we constantly underestimate the likelihood of their consequences. It feels unthinkable that, say, the American political system as we’ve known it will actually crumble.

Climate change is a perfect example of a hyperobject. The change in degrees of warming feels so small and yet the scale of the destruction is so massive that it’s difficult to comprehend in full. Cause and effect is simple and clear at the macro level: the planet is warming, and weather gets more unpredictable. But on the micro level of weather patterns and events and social/political upheaval, individual cause and effect can feel a bit slippery. If you are a news reporter (as opposed to a meteorologist or scientist) the peer reviewed climate science might feel impenetrable. It’s easiest to adopt a cover-your-ass position of: It’s probably climate change but I don’t know if this particular weather event is climate change.

Hyperobjects scramble all our brains, especially journalists. Journalists don’t want to be wrong. They want to react proportionally to current events and to realistically frame future ones. Too often, these desires mean that they do not explicitly say what their reporting suggest. They just insinuate it. But insinuation is not always legible.

Sprawling, complex, existential, without straightforward or easily achievable solutions? That sounds a lot like alcohol and other drug problems.

An understanding the coutours and frantic statements that still underestimate the consequences? Again, that sounds a lot like alcohol and other drug problems. (If you’re wondering whether we really underestimate the consequences, think about the 93,331 overdose deaths in 2020, add 95,000 alcohol related deaths, and then add 480,000 tobacco related deaths. Then consider all of the non-fatal harms to people who use ATOD — ED visits, accidents, disability, employment problems, housing problems, etc. Then zoom out and think about the effects on family members and communities. Then consider the harms associated with policy decisions, like criminalization.)

We might also wonder if the macro questions are clear, but at least some of them are clear. For example, at the population level, we know that things like outlet density and unit pricing can influence consumption. However, at the individual level, these are not obvious and do not feel true.

The concept of hyperobjects doesn’t map perfectly onto ATOD problems but they share features like being massive, broadly distributed, that “their totality cannot be realized in any particular local (individual) manifestation,” and that the impacts are visible through the interaction of multiple objects.

Bill White recently posted about the complexity related to addiction (which is only one manifestation of ATOD problems):

AOD problems, and substance use disorders as a distinct subset of such problems, do not rise from a singular cause. For most of us who have experienced it, addiction is a story of intricately intertwined threads of personal and environmental vulnerabilities, including vulnerabilities over which we had no control and were beyond our acts of choice. The most severe, complex, and enduring AOD problems rise not from a singular cause but a collision of multiple vulnerabilities. With pre-addiction stories messy and addiction stories even messier, one can find a seed of support for almost any theory of addiction causation.

Recovery is similarly complex and rarely attributable to a single factor, in spite of the passionate anecdotes of addiction survivors or this or that addiction treatment program swearing possession of the one true path to recovery. In short, no single thought, feeling, action, or environmental condition is sufficient in itself to cause addiction in all people, and no single technique, pathway, or style of recovery support is viable and sustainable for all persons experiencing AOD problems.

Hyperobjects are a slippery concept and I’m not arguing that the concept should be applied to ATOD problems, but encountering the concept provided an opportunity to step back and consider why we have such difficulty getting our minds around the problem and coming together around shared understandings and responses. It’s a massive problem, with many “objects” interacting in different combinations, different ways, and temporal sequences that cause vast differences in experiences for different people in different places in different times.

(Image: “The 3D visualization of overwhelming data ;-)” by Elif Ayiter/Alpha Auer/…./ is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)