“The Chinese use two brush strokes to write the word ‘crisis.’ One brush stroke stands for danger; the other for opportunity. In a crisis, be aware of the danger–but recognize the opportunity.” ― John F. Kennedy

Societies, like people rise to challenges when faced and decay when hard tasks are avoided. Healing for people and societies are complex, multifaceted processes that take effort. Modern society is painful and isolative. Numbing strategies have isolated our community members and eroded social capital to the point we are in a crisis. We have created a negative feedback loop as people sooth the resultant pain on both the individual and community level which then fuels isolation, substance misuse and addiction. The pandemic made all of these dynamics worse, but we have the opportunity to revisit what we are doing to address some of the underlying dynamics related to substance use and alter our course. The recovery community can play a vital role in this revitalization if given the opportunity to do so.

Soothing the hurt of loneliness will not heal us

As this recent Harvard Report notes, America is experiencing an epidemic of loneliness. 36% of respondents reported feeling lonely “frequently” or “almost all the time or all the time.” A startling 61% of young people aged 18-25 and 51% of mothers with young children reported these miserable degrees of loneliness. Stats to pay attention to!

We must address the encroaching sense of loneliness across our society in ways beyond soothing these through gambling, social media, consumerism, alcohol, cannabis, and other drugs to numb the pain. We have a menu of drugs and distractions that provide fleeting respite from our underlying malaise but not much focus on changing our course.

Most of us have seen or heard about the 2015 Rat Park TED talk. It is quite persuasive. It contains a lot of truth. Our society magnifies sad, lonely rat like conditions for a majority of us. Taking a sad, isolated people and creating conditions to help them feel happy and connected would likely reduce the use of drugs and alcohol to cope with despair. Yet, we cannot delude ourselves into thinking that addressing these societal shortcomings will make addiction disappear. We like such simple solutions, if addiction was easy to solve, we would already have done so. But the dynamics of our rat park are quite real. Addressing these societal ills is a partial solution, not a panacea to addiction.

Society is about supporting its members across the long term. Addressing the dynamics in our society that erode our individual and collective sense of hope, purpose and connection. These challenges must be addressed as central facets of prevention and healing from what we are collectively experiencing as a people to preserve a functional society.

The Pandemic has potentiated societal dynamics of isolation and despair in ways it is clear we cannot sooth our way out of. We are also faced with opportunity to consider solutions to address the underlying dynamics that are eroding our society and impacting our health and wellbeing. The costs are not borne evenly. The Loneliness Epidemic Persists: A Post-Pandemic Look at the State of Loneliness among U.S. Adults explores the disparate impact that pandemic had on these challenges. Some notable findings they highlight:

- People from underrepresented racial groups are more likely to be lonely. 75% of Hispanic adults and 68% of Black/African American adults are classified as lonely – at least 10 points higher than what is seen among the total adult population (58%). This is notably different than previous data which showed similar experiences of loneliness across racial and ethnic groups.

- People with lower incomes are lonelier than those with higher incomes. Nearly two-thirds of adults (63%) earning less than $50,000 per year are classified as lonely. This is 10 points higher than those earning $50,000 or more. Relatedly, almost three in four people (72%) who receive health benefits through Medicaid are classified as lonely, which is substantially more than the 55% of adults covered by private, employer- or union-provided health insurance benefits.

- Young adults are twice as likely to be lonely than seniors. 79% of adults aged 18 to 24 report feeling lonely compared to 41% of seniors aged 66 and older. This is consistent with earlier research.

Building Social and Recovery Capital

As previously noted, we must embrace recovery capital within our care system to save it. It should not be new information that successful treatment programs recognize the role of recovery capital and develop interventions that provide support via self-help groups, peer support, and families. We also know there are relationships between isolation and poor health in our broader healthcare system and that expanding social capital can also improve economic factors. It is a wonder that, given our current, broad societal challenges that developing connections within and across our communities is not a major policy focus here in the US. This is the crisis and opportunity we are presented with.

Where are the efforts to collectively address these challenges?

We should be seizing the opportunity hiding within the crisis to more effectively address our collective needs in a post pandemic era. There is an emerging effort to do so in the UK. This article, Post-COVID recovery and renewal through whole-of-society resilience in Cities in the Journal of Safety Science and Resilience explores one such effort. The authors note that the necessity of renewing approaches to building local resilience capabilities across the whole-of-society requires synchronization across and between formal and informal approaches – that is, “bottom-up” and governmental initiatives – to meet the diverse needs of communities.

This article examines the newly formed National Consortium for Societal Resilience (NCSR). It is comprised of business sector organizations large and small, charity organizations, governmental and academic entities. It is a broad-based coalition. The Consortium have identified the following founding principles to underpin this collective effort on whole-of-society resilience that resonate with many of us in the recovery community:

- We must align behind a shared meaning of ‘whole-of-society resilience’.

- We must exploit our synergies and the substantial opportunities from working collaboratively together.

- We are working on an ambitious issue, so we need short-term (realistic) objectives and longer-term (ambitious) objectives.

- We must be efficient in our work and facilitate researchers to provide its research capacity and support.

- We need a new, ambitious, nationally consistent foundation on which to build whole-of-society resilience.

- We will address significant resource gaps by producing materials and collateral which only contain the NCSR+’s neutral-branding and which can be adopted without charge, provided that NCSR+’s neutral-branding is retained equivalently alongside the user’s own branding.

- We must accumulate diverse good practices from which to carefully select a starting portfolio to localize as no ‘one-size-fits-all’.

- We must build the consortium into a national eco-system to coproduce approaches with the voices of our communities.

- We must analyze the impact of our effort.

- We must disseminate our learning to everyone via our events, website, outreach, and link.

NCSR holds out that we cannot be resilient on our own and they recognize that resilience must be developed from inside communities. This includes building on existing community structures and partnerships and establishing new ones. Shared understanding and joint working relationships will be key to creating an inclusive, supportive, and enabling environment for the co-production of whole-of-society local resilience capabilities. This is an approach which requires an adjustment of relationships on resilience between whole-of-society and resilience partnerships.

Even if the NCSR fails to fully achieve all of its goals, what it will likely succeed at simply by trying to do so is to strengthen social capital across the nation. It is the case that focusing on developing resiliency in diverse communities increases the kind of capital that we have been spending down rather than building up. We need to focus on rebuilding social capital here in America. How do we get a similar effort off the ground here in the US, or create more synergy around these types of efforts where they have already formed?

The challenges we are facing in reversing the alarming trends of isolation and despair run in close parallel to the kinds of things we are trying to do to strengthen recovery efforts in our communities. Recovery communities would make ideal partners in developing strategies similar to what the NCSR is being set up to address in the UK.

There are lessons here that resonates with many of us in recovery. Good things take hard work and collaboration. The more people come together, the more we see we have in common, the more we can accomplish together and the stronger we are individually and collectively. Effort yields some benefit no matter what other outcome is achieved. There is some irony in that we are learning that avoiding pain tends to only forestall and intensify how unpleasant it is once experienced. The other lesson is that no one group can address these issues alone. More evidence of opportunity posing as a crisis.

Let’s seize the opportunity to improve our society. It is an effort that will yield a vital bounty no matter what. The alternative is to sooth ourselves and our communities into further decay. It is not a tenable option.

It seems like more is being said about drug policy than ever before. I’ve been posting thoughts about drug policy here for years. However, as I read comments from others, I often wonder whether we’re talking about the same things. To be honest, I haven’t given a lot of thought to the conceptual boundaries of “drug policy” when I use the term.

As I contemplated the term, it occurred to me that I’d never seen anyone unpack all that the term could encompass. If you’ve seen something that does so, please share it in the comments.

Off the top of my head, here are some of the things that might fall under the umbrella of “drug policy.” Feel free to point out things I missed in the comments.

- The criminal status of the substance

- If possession and/or use is illegal:

- Is it a felony, misdemeanor, or civil infraction?

- What are the penalties and/or interventions?

- If it’s legal:

- Is it regulated? If so, how?

- What’s the minimum age? What’s the penalty for selling to someone underage?

- Are sales of it legal? If so, by who? The state?

- If retail, do sellers need a license? Is there any management of outlet density?

- Is there minimum unit pricing?

- Are there any limits on quantities possessed?

- Are content and potency regulated?

- Are research and development regulated to manage innovation in drug creation, preparation, and consumption methods?

- Is marketing regulated? Is targeting minors prohibited? Are billboards allowed?

- Is there any effort to manage the influence of industry groups? (limiting size, restricting lobbying, etc.)

- Where can it be consumed?

- What’s the response to public intoxication?

- Are hours/days of sales limited?

- Is it medicalized?

- Does it require a prescription?

- Is it sold in pharmacies?

- Are active ingredients subject to approval from a body like the FDA?

- What’s the tax status?

- How is tax revenue used?

- Is the tax rate intended to impact consumption?

- How is it taxed (weight/volume, potency, price, etc.)?

- Is there any attention to tax revenue creating incentives for governments to protect the industry?

- How do we manage crime that is related to substance use? (property crimes, impaired driving, interpersonal violence, etc.)

- Is substance use considered in prosecution, sentencing, and monitoring?

- Is coerced treatment an acceptable alternative to incarceration or other penalties?

- Is it regulated? If so, how?

- If possession and/or use is illegal:

- Public health policy

- Primary prevention – what interventions are used to prevent substance misuse?

- Secondary prevention – what are the practices for screening and early intervention to identify and address misuse?

- Tertiary prevention – what interventions are used to prevent the progression of established substance abuse before health consequences emerge?

- Harm reduction – what interventions are used to reduce or prevent the negative effects of ongoing drug use?

- How do we address the medical and mental health problems associated with substance use?

- Research

- How is it funded?

- Who determines the research priorities?

- Who determines what gets published?

- How does research get translated into practice?

- Treatment policy

- What treatments are available?

- What treatments are funded?

- What treatments are prohibited?

- What treatments are favored?

- What endpoints are identified and prioritized?

- What’s required of funders? Parity? Required covered services?

- What’s required of treatment providers?

- Are social determinants of health the responsibility of the treatment system, other systems, or the individual?

- What’s it like to access treatment? What’s available on demand? What hoops need to be jumped through to access higher levels of care?

- Policies related to the cultural status of the drug

- What norms are communicated in schools and public education campaigns?

- How is substance use thought of? (As a good thing, a neutral thing, an unavoidable and unfortunate part of human communities, a sin?)

- How do we conceptualize misuse and addiction?

- Is it an individual problem? A personal responsibility?

- Is it an illness? Are some patterns an illness and others not?

- How do we communicate that?

- Where harm occurs, how do we think about the harms of use that may be experienced by children, other adults, or communities?

- Who’s responsible for addressing these harms?

- What strategies are used to mitigate these harms?

- What’s the response to public intoxication or disruptive behavior related to drug consumption?

- What goals, outcomes, and endpoints are selected for treatment and public health policies?

- Where can it be consumed?

- Where are outlets zoned, geographically? (Downtowns, neighborhoods, or more industrial areas?)

- Do we create settings for communal substance use?

- Are they commercial settings, like a bar, restaurant, or cigar bar?

- Are they medicalized settings, like drug consumption rooms?

- If the substance is medicalized:

- Is there consideration of how that, at the individual level, changes object attachment?

- If there isn’t gatekeeping by a prescriber and pharmacy, how does medicalization change the threshold for initiation?

Mark Kleiman was a thoughtful contributor to discussions on drug policy, with some of the most comprehensive and nuanced takes that I’ve encountered. In the paragraphs below, I think he does a good job managing expectations and explaining our obligations to do better. (Note: He published this when terms like substance abuse and substance abuser were the norm.)

Any set of policies will therefore leave us with some level of substance abuse—with attendant costs to the abusers themselves, their families, their neighbors, their co-workers and the public—and some level of damage from illicit markets and law enforcement efforts. Thus the “drug problem” cannot be abolished either by “winning the war on drugs” or by “ending prohibition.” In practice the choice among policies is a choice of which set of problems we want to have.

But the absence of a silver bullet to slay the drug werewolf does not mean we are helpless. Though perfection is beyond reach, improvement is not. Policies that pursued sensible ends with cost-effective means could vastly shrink the extent of drug abuse, the damage of that abuse, and the fiscal and human costs of enforcement efforts. More prudent policies would leave us with much less drug abuse, much less crime, and many fewer people in prison than we have today.

Dopey, Boozy, Smoky—and Stupid by Mark Kleiman

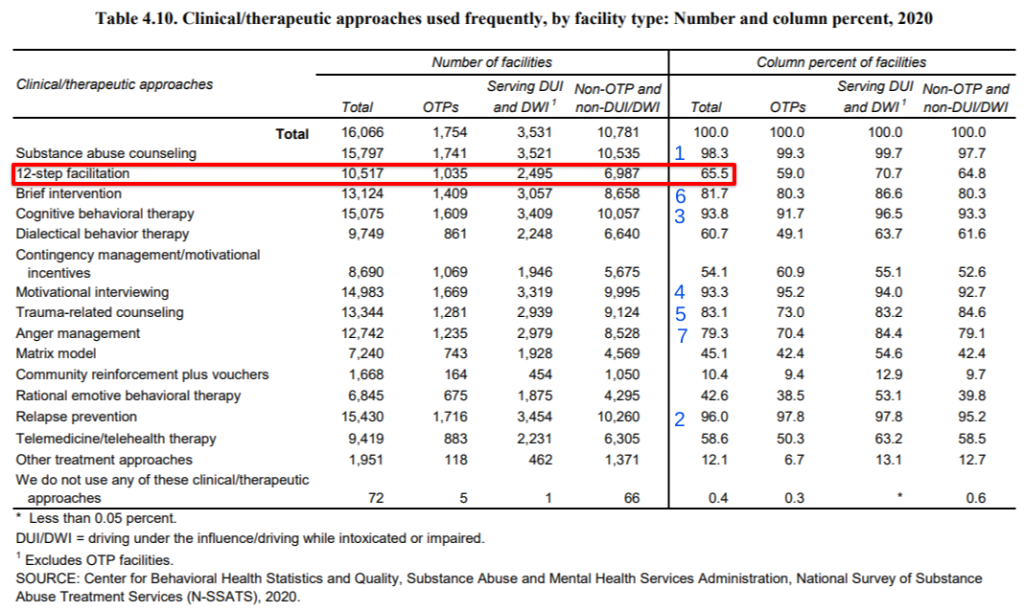

There are a lot of problems in addiction treatment, but 12-step hegemony is not the problem that advocates and media coverage would lead one to believe. (Keep in mind that 12-step facilitation is an evidence-based treatment.)

It’s worth asking why this is so frequently misrepresented.

Happiness can feel elusive, determined by what’s happening (or not happening) right now. Joy, on the other hand, is a sense of contentment one feels regardless of the current situation. It is not altered by external factors. You don’t have to wait until the trouble is over to be filled with joy. You may be wondering, “How can I be full of joy when things aren’t going well in my life?” Well, it takes a lot of effort, but the answer is simple. Are you ready? Experiencing a joy-filled life, no matter the circumstance, depends on where you choose to focus your attention. Here is a short list of things to focus on that can help bring more joy to your life:

Accept that the past is the past.

Understand that you cannot change things that happened in the past, but you can focus on the future and do what you can to make a positive impact on today and tomorrow. Joy comes in knowing that it’s not too late to turn things around. With every new day, you have the opportunity to make a better choice, to right a wrong or to encourage yourself and others to keep pushing.

Know that trouble does not always last.

Joy comes in knowing that whatever situation you are dealing with right now; it will not last forever. While going through a challenge in life, things can seem very dark. You can’t always see the light at the end of the tunnel. But, instead of focusing on the problem, focus your attention on solutions like working the 12 Steps, going to AA or NA meetings, and staying in contact with your support network.

See the good.

This is an old cliché, but it it’s true — “Things could always be worse.” Make the decision to focus on the good in every situation. It’s the old glass-half-full attitude that brings an unbridled sense of joy. Focus on the good things you have, not what you don’t have. Be grateful for what you can do, don’t harbor regret for what you cannot do.

Focusing your mind on the right thoughts can help you maintain a sense of joyfulness regardless of what is happening around you. When we realize that our perspective can shift our enjoyment of life and that at the end of the day, we are in charge of our feelings and our destiny, it becomes much easier to start finding joy in everyday life.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, like the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The post Choosing Joy: Tips to Achieve Happiness appeared first on Fellowship Hall.

Yesterday, I attended a memorial service for a former co-worker of many years. We worked together at Dawn Farm, an addiction treatment and recovery support program, where one of Robin’s roles was to teach GED classes. She was kind, warm, patient, and never harbored any doubt about our clients’ capacity to learn, grow, recover, and improve their lives. Everyone deserves someone like her in their life.

While we remembered her, some of us tried to estimate all of the people who obtained their GED with her help and encouragement. It was definitely in the hundreds.

For many of them, it was a milestone that enhanced their self-esteem, expanded their options, increased confidence in their ability to grow and recover, their expectations of themselves, and their range of possibilities. Many of them continued their education at the local community college and transferred to a university to obtain a bachelor’s or graduate degree. Of those, many played important roles in forming and sustaining collegiate recovery programs. These were not people who entered treatment with lots of recovery capital. Most of them were publicly funded, many were court-involved, and all of them had multiple prior treatment episodes. By almost any standard most of them would be considered to have high severity, high chronicity, and high complexity cases of SUD. Some of them started in low-threshold services and inched their way into the full continuum of care, while others jumped straight into high intensity services.

These conversations about her work and its place in treatment and recovery prompted me to reflect on some of the schisms in the field today.

As a starting point, I assume nearly everyone engaged in discussions about addiction and recovery has good motives. We may have different assumptions about the nature of the problem, the possibilities, or the best solutions. We may be focused on different harms, risks, and goals. Whatever the case, I assume most people want to improve the circumstances of people affected by addiction.

I think a lot of people would look at Robin’s students and assume that they are likely to spend the rest of their life struggling, and the most compassionate and pragmatic response is to seek to reduce the difficulty of their struggle. Programs that take that approach are important, we need services that meet people where they are.

Robin and Dawn Farm aren’t blind to the absence of recovery capital. However, they felt a responsibility to build recovery capital in tangible ways that addressed short and long-term needs, including long-term treatment, co-occurring disorder care, recovery-informed primary care, family support, treatments for trauma, employment support, recovery housing, social support, and, of course, GED classes.

There ought to be programs whose primary goals are to reduce suffering and harm. (To be sure, some of Robin’s students participated in some of those programs before they came to Dawn Farm and met her, and others may have struggled after their time with her and used those programs later.) While programs focused on reducing harms may feel more urgent, programs focused on building recovery capital and facilitating flourishing are just as essential to a just and equitable system. Those needs should not be pitted against each other.

I’m very concerned that the medicalization of the field will progressively eliminate roles like Robin’s–framing things like education and GEDs as extra-therapeutic issues that are the responsibility of some other system.

I can only hope there are many more Robins out there in agencies and systems that value their work.

“All systems are perfectly designed to get the results they get.” – Don Coyhis

What would happen if we treated substance use with comprehensive, individualized care and support over the long-term? We don’t entirely know; we have never fully tried that approach for the general population. We do know that the kind of care provided physicians and other impaired professionals but not the general public yield really encouraging long term outcomes, yet such care is unavailable for the rest of us. We must change this.

I have been thinking about this since listening to the Podcast The Mayor of Maple Ave written and produced by Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Sara Ganim about Shawn Sinisi, a young man from Altoona PA known in the neighborhood where he grew up as “The Mayor of Maple Avenue.” As a teen, Shawn was molested by Penn State Coach Jerry Sandusky. He then descended into trauma induced addiction. He was repeatedly failed by the SUD service system and died of an overdose on September 4, 2018, at 26 years old. I felt defeated by the end of the podcast, knowing so many people have worked tirelessly for decades in an attempt to fix the litany of staggering failures it so brutely highlighted.

There are far too many glaring flaws highlighted in this podcast in how people are served for substance use issues to delineate. It reveals a service system that is underfunded. A system in which people receive short duration care at lower intensity than needed provided by a mix of well-intended people and those seeking to profiteer off of highly vulnerable people. One developed in a world that largely defines them as unworthy of help. While listening to the episodes, I thought about all the people I know who have devoted their lives to improving care in these very systems. Candidly, I felt very demoralized by the end of the podcast that despite all their best efforts, this is what our system of care far too often yields. I have watched far too many people die in similar ways. This is the most significant motivator to carry on.

One area that our systems failed Shawn is by not providing integrated SUD and MH care, including services for trauma. My own experience on this came from when I ran a long term licensed long term treatment center for 14 years. There was a state effort to improve public SUD care by integrating MH services. We embraced it. We trained our staff, hired MH counselors, increased our medical and psychiatric services, expanded groups, and generally improved our care for our clients experiencing coexisting mental health conditions. While in some ways it worked, we never got a single extra penny to add all of this care despite all the promises it would come. Funding for care is anemic at best. People get rushed through the system of care, thinly doled out in daily increments justified with mountains of paperwork.

Eventually, all the things we added to serve these patients got cut because we did not receive a single dime to provide them. That backstory does not get told, so the public sees it as a treatment failure and blames providers as incompetent or uncaring rather than more properly viewing it as a funding infrastructure failure. Stigma affirms all the biases of un-helpable people who don’t deserve care served by incompetent providers. This is how the tape generally gets played.

The podcast also talks about the failures of Peer Support. Like most human services, they work better if we invest in supervision. We would never dream of sending workers in other professions out to work in such ways. If a student graduates from nursing school, we do not place them into a critical care setting on day one or ever without close supervision, yet this is exactly what we do in the SUD field, often because the field simply lacks the resources to do it any other way. On one of the episodes, the podcast talks about the wild west world of recovery housing. It suggests improving regulation for recovery housing, which sounds good until you consider that the costs of such oversight is saddled on the shoulders of destitute residents who live in these places. High costs push them out onto the street or a flop house if they are lucky. It calls for the integration of SUD treatment with Healthcare despite our recent survey, OPPORTUNITIES FOR CHANGE – An analysis of drug use and recovery stigma in the U.S. healthcare system showing high rates of stigma against people like me. We do not feel welcome in a healthcare system in which we experience horrible treatment and widespread discrimination.

I may sound critical of the podcast, I am not. It is top notch Journalism. The problems identified throughout it are glaring and very real. Yet, addiction is perhaps our most complex condition, and we continually want to frame it and its resolution in simple terms. I suspect for those who listen to it, it will be a sort of Rorschach test for what one sees as broken about our service system. But as a person who spends a lot of time considering how to fix things, I know that there are ten problems hiding behind every simple sounding solution.

There is no one right treatment or even one intervention we can deploy to fix everything. The easiest way I have found to highlight this is to consider cancer. When cancer is diagnosed, we know that what we consider success is five-year remission and we have a long term, varied interventional strategy entirely individualized for what works on a case-by-case basis informed by the best science we have. Cancer is a broad category of pathology that runs from ranges from slow moving cell division at the threshold of benign to aggressive, fast moving, life-threatening cellular mutation. We deploy a full range of treatments and supports when we discover cancer. We focus on long term resolution given the type of cancer a person has, the stage it is in, where it is found and how far it has spread. Complex considerations informed by science.

We know that, like cancer early intervention with an SUD is critical, the longer an addiction goes under treated or untreated the harder it becomes to resolve. At the same time this tragedy was unfolding, I was working to set up a hearing in the General Assembly on how we have lost most of our service infrastructure for young people here in Pennsylvania. Services most often don’t occur until these kids’ become adults and after they hit the criminal justice system. It is an epic failure. It took several years to set up the hearing and we have not moved the needle very far on care for young people since then, even as we are seeing trends of concern in respect to young people and drug misuse post pandemic.

I have talked about how societal low expectations that people get better set people up by establishing a system of care that provides far less than what people need to heal. We know that anything less than 90 days of care for a person with an SUD is ineffective, and yet we have built an entire care system that only provides a fraction of this to those in need in respect to treatment and nearly nothing beyond it for community support. Our treatment system is designed to provide less than the minimum effective dose of care for nearly all Americans! The analogy is knowing that one needs 10 days of antibiotics to clear an infection and only providing two days of antibiotics as treatment and then blaming the patient for not healing when their infection rages back.

Perhaps the only direction that makes sense is to examine the stability of long term recovery when it can be achieved and to work backwards from that point to better understand it and to provide more people the resources needed to get there. This is called the Five-year recovery paradigm and is based on the statistic that 85% of the people who stay in recovery for five years remain in recovery for the rest of their lives. To do so, we would need to retool our systems by:

Can we envision a system in which people can access residential care without delays or intricate authorization processes, stay there for the time they need, then return to the community to participate in age-appropriate treatment and education? If not, we should ask ourselves why such a vision eludes us. Drug overdoses cost one nation one trillion dollars annually, and alcohol and other drug related consequences eclipses those costs depending on how one measures them. We tend to see this as “those people” who did this to themselves. One of the things that Shawn’s story depicts so clearly is that it is not that simple. “Those people” are us.

No one group holds the solution, and there is tremendous inertia to keep things as they are. Our whole system is built to deliver exactly what we are getting right now. It is perhaps too large an ask to reform our whole system. What would happen if we would run a demonstration project in an average community somewhere in America and in that community, we provided everything people needed to get better over the long term? I suspect we would learn that doing so would save money and lives. Until then, it seems that the lives of those who suffer do not matter far beyond the families experiencing these tragic losses. It is time we change that, even if we only tried to do so on a small scale, perhaps it would show us that this would be worth doing in all communities across America.

The most important facet of the Mayor of Maple Ave to grasp and act on is that similar stories are unfolding all around us, and we need to act to ensure that the end of these stories include recovery and the kind of life we know can be the probable outcome for people like me when we are given the proper care, for the right duration with the requisite focus on long term support.

We owe as much to every single Shawn who seeks help from our systems of care.

As Black History Month concludes, we invited our grant writer Kenya Welch to weigh in on the immense and far-reaching impact of substance use disorders on communities of color, especially Black communities. Here’s what she had to say.

While the current overdose epidemic has been framed as a public health crisis, it has deeper, less sympathetic roots for Black Americans who were categorically criminalized during the “War on Drugs.” While attention to the crisis has focused primarily on White suburban and rural communities, communities of color, and especially Black communities, have experienced dramatic increases in substance use disorders and overdose deaths.

In fact, the rate of increase of Black overdose deaths between 2015-2016 was 40% compared to the overall population increase at 21%, exceeding all other racial and ethnic population groups in the U.S. From 2011-2016, compared to all other populations, Blacks had the highest increase in overdose death rate for opioid deaths involving synthetic opioids like fentanyl and fentanyl analogs. More recently, according to a report by the Boston Medical Center, “while white fatalities have decreased through 2019, opioid overdose deaths among Black Americans — particularly Black men — are accelerating.”

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) have traditionally fared poorly in American healthcare statistics, so the vast disparity in substance-related outcomes for Blacks in America is no surprise. In addition to historical racism in the healthcare system, there are many complex factors involved in treatment and recovery services in communities of color. Although one-size-fits all solutions would be ideal, their effectiveness is simply not reality. As SMART Recovery moves to intentionally increase our presence in diverse communities, how can we be more effective? Here are a few thoughts:

- Use local community members as trusted experts and partners. Local community members have unique insight into the needs of their neighbors. Their expertise and participation will be sought to become our partners and collaborators.

- Create holistic systems of treatment/care that can help those in recovery to access supportive services. Treatment and recovery do not exist in a vacuum, and support resources like mental health care, job training, and housing are often necessary. SMART recognizes the value of partnerships with community-based organizations that address the many intersecting issues that complicate success.

- Decrease obvious barriers that can stand between people and recovery services. For example, have in-person meetings at locations that are in diverse communities, accessible by public transportation, and at times that accommodate participant work schedules.

- Representation matters. Use training resources that include diverse communities’ voices, facilitators that practice respect for diverse cultures, and services that recognize and address complex elements like historical distrust, community stigmas, and the need for privacy and confidentiality.

- Approach services with humanity and grace. Recognize that no community is monolithic; each of us has a unique story and path leading us to where we are. Our job in the recovery space should be one grounded in respect, compassion, and grace. Our job is to open doors to spaces that are safe enough for all people to walk through.

We would love to hear your ideas on ways we can make SMART a safe space for ALL. Please feel free to add your thoughts in the comments.

Every one of us goes through times where we feel bogged down by negative emotions, triggered by traumatic or stressful events, and just generally at the end of our ropes. All this negativity can bounce around our heads all day long, serving as continual reinforcement that leads us to feel burnt out, depressed, or anxious. Luckily, we don’t have to live with these thoughts. We can choose to let go and move on. Of course, it’s easier than it sounds. Getting to a place of self-actualization and confidence doesn’t happen overnight. A great way to get started is to take a physical representation of your negative thoughts, like a scrap of paper with a few thoughts jotted down, and destroy it, by tossing it into a bonfire (s’mores optional but highly encouraged). This is freeing and incredibly cathartic as one embarks on their recovery journey. Several of the Twelve Steps touch on making amends and becoming a better version of ourselves. Consider having a releasing ceremony around a bonfire with your closest friends, family members, or even just by yourself.

What exactly is a releasing ceremony? It’s a lot simpler than it probably sounds.

- Write your most pressing resentments or negative thoughts down on a scrap of paper.

Journaling is already known as an excellent method for reflection and healing. Take that same principle of writing out what’s bothering you and apply it to a scrap of paper – just a shortened list of a few things that have been weighing especially heavy on your mind.

- Toss the paper into the bonfire.

Once you feel that you’ve gotten everything in your head onto your scrap of paper, go ahead and throw it into the bonfire. Watch as the paper, filled with resentments and negative thoughts, slowly begins to burn and crisp up, then quickly disappears among the flames. The smoke produced from burning the scraps of paper floats up high into the sky along with the stress and anxiety weighing you down.

- Toast up some s’mores and celebrate your new outlook!

Now that you’ve seen how easy it can be to let go and focus on positive things that truly matter, reward yourself (and your fellow friends around the fire) with some tasty s’mores. There’s nothing like some comfort food after an emotionally comforting experience. Who ever heard of a bonfire without s’mores anyway?!

Of course, your problems won’t just disappear after burning them up in a fire. However, you should now at least feel a bit less burdened. You confronted something that had been bothering you, looked it in the face, and tossed it away to disappear. Out of sight, out of mind. View this as the first step in a longer process of eventual healing and forgiveness, both to yourself and to those who have wronged you.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The post Tossing Negativity Into the Fire appeared first on Fellowship Hall.

You can call Steve Kind by his official title of National Support Team Administrative Assistant, and he’d be happy to answer, but it would be like calling a fully loaded Maserati just a way to get around. Steve’s role at SMART is multifaceted and extends in many directions, including outreach and marketing. And having a variety of responsibilities on a daily basis is just fine with him.

Steve has been with SMART since April of 2022, “Having used SMART Recovery on my own quest for sobriety, and later becoming a facilitator, I knew I wanted to be a part of the organization.” He now answers phones and emails, helps connect other organizations and individuals to training, represents SMART at sober events, and is helping figure out how to make SMART more prominent on the web.

Steve is especially suited for helping in the digital realm based on his previous experience as owner of a website design and internet marketing firm. But while increasing search visibility for SMART’s website gives Steve a kick, the real positive of his job is in being there for people, “The most rewarding thing is to have someone reach out to us in need of help and end our communication with them excited to have found a recovery path that works for them.” The excitement goes both ways.

Here are Steve’s responses to the Take 5 Spotlight questions:

- Are there tasks you perform regularly during your workday? I am the frontline for all incoming phone communication. I respond to all general email inquiries or route them to the appropriate team. I make outreach calls and track progress.

- What are a couple of the ways you interact and coordinate your job with national office staff? I interact with the national office staff on a daily basis by either connecting the appropriate staff with the incoming communication or by coordinating with them in outreach efforts.

- What is one of the ways that you think you personally make/want to make a difference at SMART? I don’t have an off button. Whatever is asked of me to help grow the organization I am happy to do. I want to see meetings available in every area of the countries we serve. Dogged determination, and a lack of fear in approaching those who could help with that effort, are what I bring to the table.

- What is your message to all those dedicated SMART volunteers across the country?

I find their passion for helping others inspiring! Our volunteers devote their time and skills to making a difference in people’s lives, and I applaud them all. - What kinds of things are you interested in outside of work? Any hobbies?

I love reading and writing. I have authored a book and enjoy reading books on a wide variety of topics. I enjoy traveling, trying new things (especially ones that scare me), and meeting new people. I can be happy with a crowd at a concert or sitting quietly with a good book. I also enjoy a good movie now and then…but they’re usually not as good as the book.

The bottom line for Steve, no matter what title he might be assigned, is that his work is a response to real human beings in need. And that makes individuals approaching SMART from any direction bound to hit their target of getting help.

Learn more about the Take 5 Spotlight series and see others who have been profiled.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline @ 988, https://988lifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

‘I notice you’re not drinking, David’, she said. It was more of a question than an observation, but I didn’t answer. We were in an upmarket restaurant having a meal with our professional peer group celebrating the successful delivery of a teaching course on addiction treatment. My colleague, a fellow addiction specialist (not a current or recent colleague), was sitting opposite me at the table, her wine glass full.

I’d been in this situation before, several times in my recovery, and, as it turned out, would be interrogated subsequently and recurrently by others on my choice not to drink. I could have said, ‘Well if I were to drink, I could end up losing my wellbeing, my good mental health, my job, my relationships, and my freedom to make healthy choices’, but I was two years into recovery – early days – and I didn’t want to disclose my history of alcohol dependence at that point.

Unsatisfied, she began to speculate on my alcohol-free status. ‘Are you driving?’

I said, ‘No Pamela,’ (not her real name) ‘I am not driving’.

Like a cat with an antagonistic mouse, she went on, ‘Are you up early tomorrow then?’

‘No, not particularly’, I responded.

‘Perhaps you had a heavy drinking session last night?’ she asked.

‘No, I didn’t.’

She fixed her gaze on me, determined to have an answer. ‘Well David, why are you not drinking’?

I gave in, not so much out of resignation as mischief. ‘As it happens Pamela, that’s because I’m a recovering alcoholic’.

She looked at me without expression for a second or two longer then turned her head abruptly to the side and said to her neighbour, ‘Hasn’t the weather been terrible recently?’ We didn’t return to the subject again.

Unlikely as it seems, I promise you that this is exactly the way the conversation went.

There were three things that I took away from that encounter. The first was that my not drinking disturbed her. The second was that my disclosure of being someone in recovery was not something she wanted to acknowledge. The third takeaway was that this indirect pressure for me to drink represented a tangible risk at this early stage in my own abstinent recovery.

Let’s be clear, most people are not bothered by someone who does not drink – after all more than 20% of the population in the UK is teetotal now (higher still for younger people), but where there is resistance, discomfort or challenge, there is usually something else going on.

I’ve been challenged several times at social gatherings about not drinking – ‘Surely you would take a drink if you had something amazing to celebrate? What if someone gave you a gift of a rare single malt whisky – you’d want to taste it – right?’ As it turns out, malt whisky was my drink of choice, so not ideal to be challenged in this way really.

I think such questions come from an often-unrecognised unease around the questioner’s own relationship with alcohol. I certainly had an unhealthy interest in friends’ drinking when amid my own alcohol problems. There is a culture around drinking and often a societal pressure to drink. Not to drink can make you ‘other’.

Early recovery is a challenging time. Relapse never feels very far away and although it’s fairly unlikely many others will experience risky encounters with addiction specialists in social settings, it would be foolish to ignore the very real crocodile-infested waters that can exist for those of us making the perilous passage to recovery. One of those risks relates to advertising.

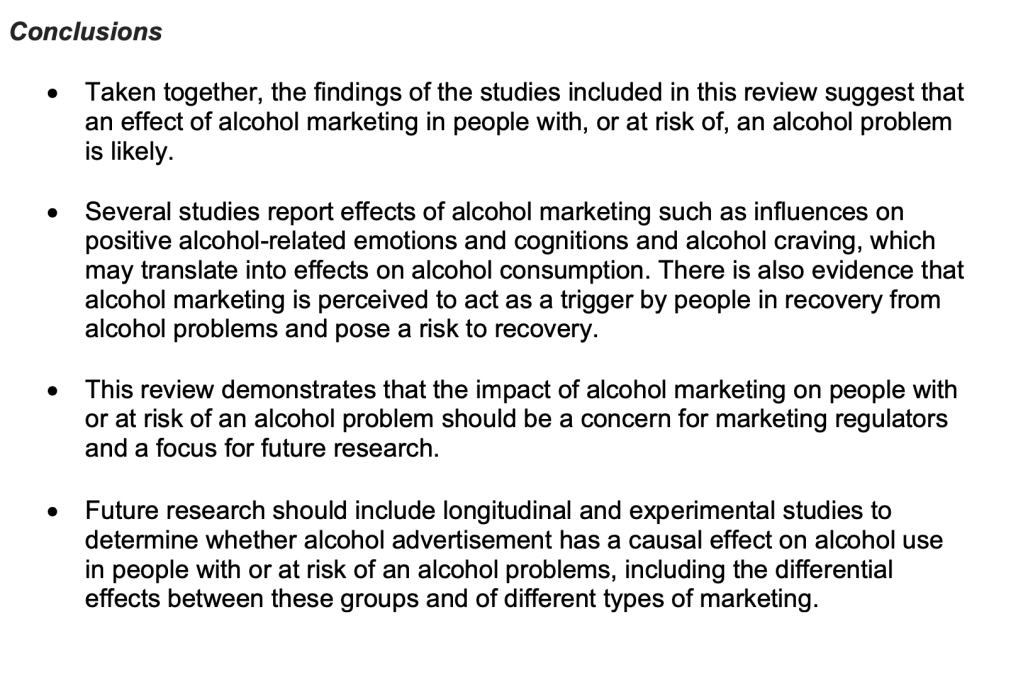

Although there is not a great deal of research on how alcohol advertising impacts those in recovery, the research which is available shows a high level of awareness of alcohol advertising in this population with concerns that such ads trigger craving. The Alcohol Health Alliance published a blog a couple of years ago where two people in recovery shared their challenging experiences of being exposed to alcohol advertising in an impossible-to-avoid way. The vulnerability is clear.

It is everywhere – the ads you see on the TV during commercial breaks and during football matches, to the cut price drink deals that follow you around the supermarket from the moment you walk in.

Peter

A rapid review of the literature from last year conducted by researchers at the University of Nottingham, reported by Alcohol Focus Scotland, found there was cause for concern (see box below).

When I joined Twitter a couple of years ago – tweeting about recovery, not drinking – I found myself inundated with adverts for alcohol and had to block them one by one. Interestingly, they were then replaced by adverts for gambling sites. I found the unwanted images frustrating, although not particularly risky, but in early recovery I would have been very reactive around these.

I generally avoid temptation unless I can’t resist it

Mae West

The Scottish Government is currently consulting on reducing alcohol marketing to reduce the appeal of alcohol to young people and reduce risk to higher level drinkers and those in recovery.

For many of us who have severe alcohol use disorders, early recovery is tough. We are vulnerable. While recovering people might want not to drink, the alcohol industry is pretty indiscriminate in its approach. Like the addiction specialist in that restaurant all those years ago, their question is also, ‘Why are you not drinking?’. They then add, ‘You ought to be.’

We need to be supporting people on their recovery journeys and trying to help to reduce triggers. Limiting marketing is one of those ways. If you have any thoughts on this, take some time to participate in the consultation.

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

Picture credit: Robert vt Hoenderdaal (istockphoto) under license