Forward: Johnny Allem has a long and honorable history in service to the recovery community. In the preparation for this interview, I learned of a connection between my organization, PRO-A and Johnny I had not known about. PRO-A was formed in 1998 to bring together the statewide recovery community of Pennsylvania. In those early days, as our board was being formed, they invited Johnny to come up to Harrisburg and to share the lessons learned during the years he led the Society of Americans for Recovery (SOAR). I learned that the very day the Board met with him, one of our board members left that meeting and ran into Dona Dmitrovic in the hallway. She was working in the same building for a human service organization, and he realized she was the perfect candidate for Executive Director. She took the job soon after and started her work in the recovery arena. Two weeks ago, when I was trying to set up this interview, I asked Dona if she could introduce me to Johnny and she did. She got to know him because of her work a few years after assuming leadership of PRO-A. Johnny responded almost immediately and he was gracious with his time in order for me to conduct this interview. To me, it feels like a loop closed, the connections have come full circle over two decades later.

Johnny Allem has been active as a leader in the national advocate for addiction recovery for all of his nearly four decades of recovery. A co-founder of Faces and Voices of Recovery, and former Deputy Commissioner of the DC Mental Health system, he currently leads Aquila Recovery Clinics, an outpatient recovery clinic he founded that features integrated mental health and substance use care. He was the 2016 recipient of the William L. White Lifetime Achievement Award of Faces and Voices of Recovery, a member of the 2004 Institute of Medicine’s historic panel on addiction health that produced Crossing the Quality Chasm – Adaption to Mental Health and Addiction Disorders and was featured in the ANONYMOUS PEOPLE, Greg William’s 2015 film celebrating the vitality and importance of the addiction recovery movement and its power to change minds. He is a former President of the Johnson Institute, featuring the pioneering work of Vernon Johnson, credited with “raising the bottom” for people entering recovery. His career includes five decades of civic, political, business and healthcare interests. As the President of the Johnson Institute, a policy organization, Mr. Allem developed and conducted training for more than 2,000 “Recovery Ambassadors.” Allem’s addiction recovery story is featured in Gary Stromberg’s book: “Second Chances: Top Executives Share Their Stories of Addiction and Recovery.”

- Who are you and what brought you to St Paul at that time?

Before getting involved with what became known as the recovery movement, I had done about a hundred things in my life. To name a few, I did sales, I was a news reporter, a sound engineering and eventually politics. From 1962 to 1982, I was a political consultant, representing over 125 campaigns. I also contracted with the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) union, where I developed the PEOPLE political action training program that ended up being provided to more than 90,000 union members. This experience helped shape our work later on when I traveled the country with Dona Dmitrovic and facilitated the Recovery Ambassadors project through the Johnson Institute.

I got into recovery in 1982 and relatively soon after got involved in recovery efforts, first working with the Mayor of DC starting around 1985 when he appointed me to the Mayor’s Advisory Commission on Alcoholism, and then with the formation of the SOAR that was started by Harold Hughes. Hughes had been governor of Iowa from 1963 to 1969 then and a US Senator from 1969 to 1975. I had done a lot of work in the political field and I had worked for him when he took a short run for the Presidency back in the 1970s and I knew he was the author of the Hughes Act, the first step the federal government took to recognize addiction as a disease. Back then, he was sober, and I was still drinking. Senator Hughes made quite an impression on me even then. A few years after I got into recovery, he asked me to run SOAR and I agreed to take the job. SOAR had a brief history; it ran about three or four years, but we set the groundwork for much of what came later. We had the right ideas, but the timing was wrong.

We were trying to SOAR off the ground in the early 90s, right around the time the war on drugs was heating up. It had a real chilling effect on people being willing to identify as being in recovery. The war on drugs campaign ended up demonizing drugs and people who have substance use conditions. This also made it very difficult to raise money for organizational efforts like ours. We ended up getting supported with the nickels and dimes individuals could give us and we did get some institutional support through a handful of treatment programs, but it was just not enough. SOAR folded despite our best efforts.

But Harold Hughes had the right vision, to engage and mobilize citizens in recovery. He was an amazing person. A real gem. He had this deep booming voice and he captured so much of the recovery experience so well. He was a gifted communicator. He believed to his core in the power or recovery to transform lives. He was a salesman and was able to capture the essence of what we needed to do. We traveled the country and did rallies in several cities including Baltimore St Louis and Santa Monica and our efforts were well received. We knew our direction was the right one. We had the right message but, unfortunately it was the wrong time. As an aside, Senator Hughes health declined fairly rapidly shortly after that time and he died in 1996. He was aware of what we were doing to organize that summit. I think he had the sense that all the work we did with SOAR and his early Senate hearings and other organizational efforts was moving forward. I wished he had lived long enough to see that summit; he played a pivotal role in laying the foundation for what came next.

It was not until the mid-90s when things started to change. At that time, there was a growing recognition within government that there needed to be an emphasis on including constituent groups that were represented and served by government. The Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) formed an advisory group at that time and I was the first person in recovery tapped to serve on that advisory panel. For a period of time, I was the only one, but they added more as the commitment for recovery representation increased. Outside of government, recovering people and our allies started to realize that the time was right to set our own table, to bring recovering people together and unify around efforts to get more Americans into recovery. We started to plan the summit. The Johnson Institute played a significant role in it, as did Hazeldon, the Legal Action Center and others. There were some key players like Bill Moyers and Jeff Blodgett and we started to plan the summit, which ended up being set for October, 2001 in Saint Paul as you know. That was an era well before zoom. We had our planning meetings face to face. I flew out to Minnesota a number of times as we prepared the summit. We worked hard on a unifying strategy. We emphasized many pathways to recovery and planned the event in ways that would emphasis the transformative power of recovery. We know this is how recovery works, but the public had no idea. Addiction was seen as a moral issue, not a medical issue or one in which recovery was even possible. The war on drugs had increased the stigma and demonization across America. We were seen as hopeless causes even as millions of us around the country were thriving.

- Is there a particular moment or memory that stands out to you from that summit?

I already knew most of the people in that room, but when I walked into it, I was stunned by the talent that was assembled. I could feel the energy and optimism. Most of my life, I have been a talker, I found myself in a deep listening mode as I took it all in. I could see that we had the right message, the right people to communicate that message and we had them all in the room together for the first time in history. I was an organizer, and I knew what we had the moment I walked into that room. It was a moment I will never forget. We had a story to tell that desperately needed to be told to a world that needed to hear about the power of recovery to transform lives.

For me personally, this was the moment that I bonded with many of the attendees in a much more significant way. We were moving from a collection of individuals into a unified group. I think that other people in the room felt it as well. There were 235 invitees to the summit, and I do not think I was able to spend time with them all, but I sure tried. We formed stronger bonds, which allowed us to do so very much after we left Saint Paul. I recall my conversations with Bill White during that summit and we talked about the energy of the group and the possibilities in front of us. I talked with Carol McDaid and I think she saw some of the same things. I knew them both, Bill through our work to organize the summit and Carol as our SOAR offices were in the same building in DC where her offices were. The summit created a deeper bond of common experience for so many of us.

- What did you see as the motivating factors that brought you all together for that historic summit twenty years ago?

Hazeldon gets a lot of credit for the support they provided us, as did the Johnson Institute, also Bill Moyers as well as Paul Samuels from the Legal Action Center. All the energy was there, and we were finally in the right moment to bring it all together. It was an opportunity to build some unity and heal our divisions. Historically, our whole field has been so very divided. The early 90s were a clear example of what happens when we have no unified voice. In that era, we lost about half of our residential SUD treatment system as the insurance industry squeezed out care. A lot of people died. This was in no small part because we had no unified voice. Everyone was divided up, family groups, persons in recovery, the research community, treatment providers. There was so much infighting. It decimated us all. No other area of healthcare has been and to some degree remains as divided as we are. Our primary motivation for the summit was to unify around recovery. We did so because we could all see that that division made us ineffective at getting resources to help people. This was killing our friends and family members. It is an important thing to remember that we are that proverbial house that divided cannot stand.

- How have we done in accomplishing those early goals?

One of the most important things we accomplished was that we showed we could stand together. That in itself is huge. Getting people to stand up and share the power of recovery to transform lives was a highly effective strategy to shift public perception about addiction and recovery. We showed that it is possible for people to talk about recovery openly. It was now possible to do this while still protecting individuals in early recovery who needed anonymity. It is important to recall now how that there was some hesitancy to stand up and be open about recovery. When I started to do so in the mid-1980s I actually got calls from people telling me I was going to relapse because I was openly acknowledging my recovery. Some people in 12 step recovery confused anonymity at the level of the group with personal anonymity. We showed that we can talk about the transformative power of recovery in ways that honored the need for anonymity at the level of the group. That was huge. Our efforts in that era on this facet of our goals is now visible all around us. Recovery is now elevated to the level of public awareness. It is now easier for people to seek help because of these efforts.

We established ourselves as a legitimate citizen constituency. We are not supplicants looking for a handout, we are respectable people who productively participate in all facets of society. We have earned every right to be seen as a constituency and to be respected and included in matters that impact our community. This focus on positive citizenship was a key facet of our messaging, we were determined to show we are part of the essential fabric of our vibrant society. People get into recovery and do great things. We thrive. We build businesses, we do civic service in our communities. We are not people to be ashamed of, far from it. We represent the very fabric of a resilient and healthy community. The time was right to come out of the shadows and be counted as respectable and civically engaged members of society.

- What do you see our greatest successes to date are?

I think there are two things I want to emphasis here. The first is the work we did to organize people in recovery. To show them how to message recovery in ways that challenged negative public perceptions about us. We showed America how recovery is about empowerment. We needed to focus on getting our message out in ways that it could capture the essence of who and what we are. No more hiding in church basements. The Johnson Institute saw the possibilities of what was coming together and three weeks after the summit, I was brought on as the President. I used the knowledge and experience I had gained in my earlier life work in politics and in organizational efforts through the Union to put together the Recovery Ambassadors Leadership Training Program. Dona Dmitrovic and I went around the country and worked with over two thousand people. We helped build a citizen force of people in recovery who could begin to talk about recovery in ways that fundamentally changed the narrative. We began to push back against the moralization and demonization of addiction that has shaped the war on drugs mentality that took hold in the 90s. We began to move conversations from a deficit and shame focus to a strengths and hope focus. The evidence that this worked is all around us today.

The second thing we did was begin to pull together all of the varied organizations working in the addiction and recovery space so we could develop common ground. The Johnson Institute would rent out the National Press Club in DC twice annually. We regularly brought in 42 organizations from around the country to focus on our common goals. It was transformative. Every session would start out with a focus on the science – we made sure we were including the most recent research on addiction and recovery at every single meeting we held. We all sat in a room and worked together to reduce the fragmentation of our field, then everyone went out and networked at lunch. Faces & Voices was there, Legal Action Center played a key role. Our ability to bring organizations together was really important and helped everyone understand that we needed to work together to build. A system of care that met our needs and to work together to pass laws and advocate for policies to end discriminatory insurance and funding practices. This effort we were involved in cannot be understated. It helped us pass the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 1996.

MHPAEA was a huge victory, even though we still have a long way to go yet with it. I don’t think many people know that it is the only federal law that pushes enforcement down to the state level. This is a huge barrier to implementation, and industry got it in there intentionally to make enforcement hard. All these years later, and we are still working to get this federal law enforced. It is a testament to the kinds of industry lobbying against it that we are still having to fight so hard even as our friends and families cannot get the care they need. Our people are still dying. But we stay at it. Look at the lessons of the past, we know to never give up. We keep at it, knowing that the right time will come, we will get insurance parity in this country despite all the market forces lobbying against it. We will do so because the facts are on our side. The reality is that recovery is the probable outcome when people get the services and supports they need. I know we will prevail, hopefully in my lifetime.

- What did we miss if anything looking back at those goals?

I would circle back to that discussion on disunity I mentioned in the answer above. What has historically happened in our field is this fragmentation has been used by groups who have vested interests in keeping us divided to further their own political agendas at the expense of our people. We are still fighting for its enforcement of the parity act a generation after it was passed into federal law. We have some ways to go in order to establish the kind of political unity and political platform to combat the forces that divide us. There is no time like the present to work on that. It all comes down to a focus on developing a citizen force and field unity. We must continue to work towards that. But what we did accomplish was to change public perception. We can see now that a large segment of the general public see addiction as a public health issue and not a criminal justice problem. We did that. Unfortunately, they still see it now as an illness we chose to have, like we went to the store and bought addiction. That is the next thing we need to change.

We have come a long way and we have a long way to go, but we are making some progress. Putting a public face on recovery and establishing an active citizen’s force was not possible in 1987, or even to the degree we have it now when I look back to 2007, but the multitude of individuals and organizations that are drawing attention to the benefits of recovery in recent years are changing public perception in ways we could only dream about back in 2001. We did that. What comes next?

- What are you most concerned about in respect to the future?

The only thing that really concerns me is the possibility that we may not put enough emphasis on getting a handle on public policy and on funding mechanisms. We must work towards getting our people a fair shake. We have had our best successes when we have seen bipartisan efforts to support recovery. Addiction is not a partisan issue; it kills Democrats and Republicans just the same. We live in hyper partisan times, so to ensure that recovery remains out of these hyper partisan fights will require a lot of carefully considered strategies.

We certainly have some difficult roads ahead to navigate, but we have every reason to remain optimistic. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr famously said that “we shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” The evidence of the truth of these words are visible to anyone that learns anything about the history of recovery in America. We have the right message and the right messengers. We just need to stay at it. We must never give up but sustain our efforts for as long as it may take. There are millions of Americans whose lives depend on us never giving up. The right wave will come along and carry us to shore. Such a day will come sooner rather than later if we can sustain a unified message of hope, recovery and positive citizenship that personifies recovery.

- What would you say to future generations of recovery advocates about what we did and what to be cautious of / your wishes for them moving forward?

The change began on our watch, but the change will more fully come to fruition in the next generation. When I speak with an audience of young people about how things were in our era, they find it hard to believe. So much has changed. It is now incomprehensible to them that there was a time, up until just a few years ago that people hid their recovery as if it were an embarrassment. It has moved from a place of shame to a place of worthiness. I tell them yes; you have an illness but you have an illness which the recovery from it makes you a stronger person.

We have also made progress in respect to seeing the connections between mental health and substance use issues. It was a ping pong ball of BS for so long. Which one came first, what caused what and which one we should treat? We still see some agencies embroiled in these internecine battles and downplaying the devastation of addiction and the promise of recovery. I would tell them to keep moving forward and build care that addresses all facets of mental health and substance use needs and not downplay the value of recovery. We must move forward and build a care system founded on good science that supports long term recovery for every American.

They are going to need to work hard and find ways to work together, but if they stay at it and keep their eye on the prize, I am an optimist of what they will accomplish. In 2008, Bill White did an interview with me. In that interview he asked me about what kind of recovery advocates will be needed in the future. I said at that time:

“The message we need to convey is, not “I am the solution,” but “We are the solution.” This is a movement expressing the will of a community of recovering people, not one relying on a few charismatic leaders. I think it’s important that we continually build this movement from within. We have to be committed, competent, and comfortable being an advocate and pass those traits onto others working alongside us.

Bill, I am not sure I could say it better today than I did back in 2008. What was true then remains true now. We are the solution, and we will prevail if we can carry the message of recovery and the vital role we play as a citizen force on to the next generation. This is my hope, this is what so many of us have worked hard to make a reality. I am hopeful of our long tradition of recovery service. It has carried us this far, I believe it will carry us forward for many generations, just as those before us worked for and hoped of us. We really are part of something bigger than ourselves. When we keep that perspective in our hearts and go forth and humbly serve others, we always prevail in the end. If that has not happened yet, the story is just not over yet!

By Paolo del Vecchio, MSW; SAMHSA Executive Officer

As a person with lived experience of mental illness, addictions, and trauma, I consider July 26 - the 31st anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) - to be our nation’s second Independence Day. For the millions of us with disabilities, it is a day to celebrate our freedom. Freedom from discrimination and the barriers that block our inclusion in community life. Freedom from unjustified segregation and institutionalization. Freedom to earn and to learn. Freedom to pursue recovery and receive services and supports – including mental health and addiction services – that help us participate fully in American life.

As an employee with SAMHSA for over 26 years, I am proud of our leadership in protecting the rights of people with mental illness and/or addictions including:

- Advocating for the Rights of People with Mental Illness. SAMHSA administers the Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness (PAIMI) program that supports agencies in all states and territories to investigate abuse and neglect, address civil rights violations, and enforce the U.S. Constitution, Federal laws and regulations, and state statutes. Many PAIMI agencies have helped enforce the ADA.

- Reducing and Ultimately Eliminating Seclusion and Restraint. SAMHSA works to prevent and end the use of seclusion and restraint given it can result in trauma, psychological harm, physical injuries and death to both people subjected to and the staff applying these techniques. In so doing, SAMHSA recognizes the need to develop alternatives to the use of such practices.

- Enforcing Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Parity. SAMHSA, along with the U.S. Department of Labor and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), provides oversight of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 that requires health insurers and group health plans to provide the same level of benefits for mental and/or substance use treatment and services that they do for medical/surgical care. Information on knowing your parity rights is available in SAMHSA’s publications.

- Guarding the Confidentiality of Substance Use Disorder Patient Records. SAMHSA establishes standards for the appropriate and allowable disclosure of addiction treatment records.

- Protecting the Civil Rights Protections for Individuals in Recovery from an Opioid Use Disorder. SAMHSA collaborates with the HHS Office of Civil Rights on civil rights protections for individuals receiving Medication Assisted Treatment.

- Helping People with Mental Illness and/or Addictions Involved in Criminal Justice Systems. SAMHSA’s GAINS Center for Behavioral Health and Justice Transformation expands access to services for people with behavioral health disorders in contact with the adult criminal justice system. This includes improving law enforcement response to people in mental health crises that too often results in tragic outcomes.

- Facilitating Community Living. SAMHSA collaborates with CMS and the Administration for Community Living in promoting Home and Community-Based Services, older adult mental health, and peer and family support. SAMHSA also encourages self-directed care approaches in behavioral health.

- Advancing Behavioral Health Equity. SAMHSA works to reduce disparities in mental health and/or substance use disorders across populations. This includes support of the National Network to Eliminate Disparities in Behavioral Health.

- Involving People with Lived Experience. SAMHSA is dedicated to involving people with mental illness and/or addictions in the planning, delivery, evaluation, and policy formulation of behavioral health services. This includes encouraging shared-decision making and psychiatric advance directives in clinical care.

- Promoting Recovery and Recovery Support. SAMHSA’s Working Definition of Recovery states that “protecting…rights and eliminating discrimination – are crucial in achieving recovery.” SAMHSA focuses on the four major dimensions that support a life in recovery: Health, Home, Purpose, and Community.

Over the past 31 years, America has made significant progress in protecting and enforcing the civil rights of people with disabilities – including those of us with mental illness and/or addictions. Despite this progress, we have much more work to do to realize the full promise of the ADA. Too many of us are still without the freedom that all Americans deserve.

Sitting next to President George H.W. Bush, on July 26, 1990, when he signed the ADA into law, was renowned disability advocate Justin Dart Jr. As we continue our pursuit of justice and freedom, let us remember and heed Dart’s call to action to “Lead On!” Happy 31st Anniversary of the ADA!

A version of this post was originally published in October 2019.

I like this twitter thread a lot.

Thread:

Clinician-professionals…

until the 1980s: We don’t want to treat addiction it's too hard and you're too difficult go to AA and these rehabs that'll link you to AA they can help. (1/5)

— Brandon Bergman, PhD (@brandonbphd) October 30, 2019

In the 80s and 90s: Ok so we are sorry about all that stigma now we got some good treatments and realize addiction is a medical condition and should be integrated into health care. (2/5)

— Brandon Bergman, PhD (@brandonbphd) October 30, 2019

In the 2000s: But wait didn't you hear us we said we have good treatments?! We get it we abdicated our responsibility and we are ready to help. (3/5)

— Brandon Bergman, PhD (@brandonbphd) October 30, 2019

Current: This is exasperating! Ok let's criticize as strong as we possibly can this system of care that we helped create by abdicating our responsibility -- maybe that will change things! (4/5)

— Brandon Bergman, PhD (@brandonbphd) October 30, 2019

Future (hopefully): Ok we are ready to listen. We really want to help. What can we do to understand your views on addiction and recovery? How can we make it so that you'll adopt all these treatments that we have seen are really helpful?! We are all in this together. (5/5)

— Brandon Bergman, PhD (@brandonbphd) October 30, 2019

I’d like it more if that last tweet was a little different.

I like the desire to understand patients’ and recovering people’s views on addiction and recovery.

What I like less is that it sounds like this understanding is not an end in itself. It is sought with another end in mind–to get recovering people to “adopt all these treatments” rather than achieving understanding and then deciding upon a course together.

What might be better?

Maybe we could learn something from mental health patient advocacy.

Pat Deegan works to support mental health patients’ self-determination and pursuit of the best possible quality of life.

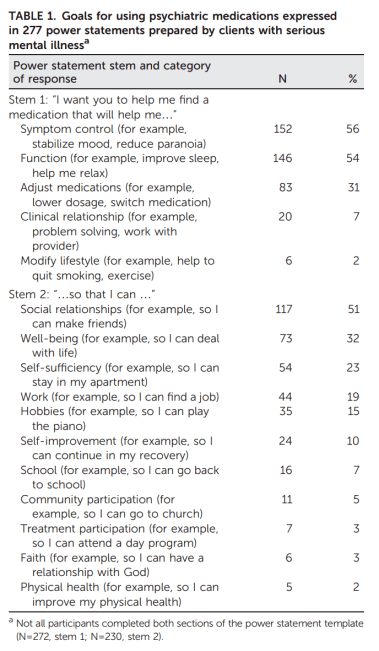

One of the strategies she uses is called Power Statements. What are Power Statements?

Peer staff, case managers, and therapists are trained to support clients in creating power statements in the waiting area of public mental health clinics by using a worksheet that guides users in filling out a two-part stem: “I want you to help me find a medication that will help me . . . so that I can. . . .”

Importantly, Power Statements are dynamic.

With support from peer staff, clients update their power statements prior to appointments as needed, for instance when clients’ goals for treatment have changed. Power statements—typically two or three sentences saying something about the client as a unique individual— state how she or he wants psychiatric medication to help and invite clinicians to help achieve these goals for medication treatment. These statements amplify the client’s voice and sense of control, while communicating concisely the client’s specific goals for using psychiatric medications. Toward the beginning of the appointment, psychiatric care providers often read the power statement aloud and ask, “Is this still the goal for our work together?” Clients and psychiatric care providers have reported that the process enhances communication

What do power statements sound like in real life? This table from her paper will give you a sense.

So . . . what would it be like if addiction treatment providers embraced Power Statements? What if there was real collaboration around choices about whether to use medication, to what end, how success is defined, and how to evaluate outcomes?

What would it be like if patients were encouraged to think about and share what they want from treatment? And, if providers listened to that?

What if providers and researchers started critically evaluating what goals each treatment (medication or otherwise) is effective, ineffective, or contraindicated for?

Maybe Power Statements are the way out of all these MAT battles? There are a lot of parallels. IDK. Just a thought.

A version of this post was originally published in January 2018.

[Cross-posted at williamwhitepapers.com]

Addiction counseling has become an increasingly professional and pristine affair, and service relationships reflect a more detached process than in years gone by. And yet one worries about the loss of something precious in our current fixation on the technical mastery of evidence-based counseling practices. We would suggest that this endangered precious quality is captured in a word rarely if ever written in the professional counseling journals or spoken in addiction counselor training programs. The word is LOVE.

Today, love in the context of addiction counseling is more likely to be thought of in terms of ethical violations than a quality of the most effective addiction counselors. But having trained and supervised addiction counselors for decades, we contend that the most effective of such counselors bring a deep, non-possessive love of those they serve. The importance of love as a foundation of addiction counseling is understandable only when one considers the historical disrespect, contempt, and even hatred those with the most severe, complex, and prolonged addictions have so often experienced in their encounters with helping professionals.

Few health conditions are so deforming of character that one’s humanity gets lost in what is sometimes a most unlovable veneer. No one can be expected to love traits so endemic to addiction. What distinguishes the best addiction counselors and recovery coaches is their recognition of such traits as an expression of the disorder and not the essence of the person. The guiding mantra of the best counselors is a very simple one: hate the disease, love the person. In our preoccupations with the technologies of effective addiction counseling, we must not lose a much more foundational requirement: the ability to not just accept and respect those with whom we work, but to love the person beneath this unlovable veneer.

Below are a few quotable observations that set the value of such love in perspective.

What is this attitude that I call the key to successful [alcoholism] treatment? First, it is accepting of the other person just as he is, for exactly what he is. Second, it accords him the dignity of his humanity quite apart from his illness which may have buried that humanity deep out of sight. He is regarded as a person, in great trouble to be sure, but not a non-person for all that. Third, it offers him understanding and, as a result of that, compassion, or as many recovered alcoholics flatly put it, love. Finally, and perhaps most important of all, it exhibits faith, a belief that he too, this alcoholic whoever he may be, can and will recover.….[Too many professionals are] condemning, and therefore often hostile. They are quick to blame the alcoholic for his condition and to see the horrors of the condition as the man. They unwittingly treat him as less than human because he is not as they are. They are contemptuous of his weakness, his failure to stand up to life. They are sometimes punitive, believing that what he really needs is to be taught a lesson. They do not understand him and so they do not really like him. And he knows it….The first requirement for successful counseling of the alcoholic is the correct attitude….If you don’t have this, then it doesn’t matter how many techniques you use, they aren’t going to work.

Marty Mann, 1973, Attitude: Key to successful treatment. In: Staub, G. and Kent, L., Eds. The Para-Professional in the Treatment of Alcoholism. Springfield: Illinois: Charles C. Thomas Publisher

I can remember in my own time some of the early NAAC and NAADAC awards going to people who were obviously not educated. You could tell from their choice of language when they stepped forward to receive the awards. But what they had was so much more important than that. They had love. They had a passion for helping within them that was so powerful that they were selected by their peers—many of whom had all kinds of degrees—to receive outstanding awards. They represented the soul of alcoholism counseling as it originally existed. They had the power to help somebody understand that he or she is a loveable human being and a child of God. This is a quality that is hard to transmit in a classroom.

What the addiction counselor knows that other service professionals do not is the very soul of the addicted—their terrifying fear of insanity, the shame of their wretchedness, their guilt over drug-induced sins of omission and commission, their desperate struggle to sustain their personhood, their need to avoid the psychological and social taint of addiction, and their hypervigilant search for the slightest trace of condescension, contempt or hostility in the posture, eyes or voice of the professed helper.

William White, The Essence of Addiction Counseling, 2004

Four things have allowed addiction treatment practitioners to shun the cultural contempt with which the addicted have long been held: 1) personal experiences of recovery and/or relationships with people in sustained recovery, 2) addiction-specific professional education, 3) the capacity to enter into relationships with people with severe AOD problems from a position of moral equality and emotional authenticity (willingness to experience a “kinship of common suffering” regardless of recovery status), and 4) clinical supervision by those possessing specialized knowledge about addiction, treatment, and the recovery process. We must make sure that these qualities and conditions are not lost in the rush to integrate addiction treatment and other service systems.

So let’s review. The experience of addicted people with professional helpers is often characterized by:

- condemnation and hostility,

- blame for their condition and circumstances,

- conflating the illness and the person,

- objectifying the person due to their illness;

- contempt for the person’s perceived “weakness” and failure at life, and

- a desire to punish and “teach a lesson.”

In short, traditional professionals don’t understand this person masked by addiction, they don’t like this person, and he/she knows it.

But such attitudes are not restricted to allied professions. They can be found within the addictions treatment and recovery support fields among those filling diverse roles–regardless of their personal recovery status. All of us are imperfect human beings. All of us have had thoughts and feelings within the helping process that we are not proud of. Encountering such thoughts and feelings is not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when. The key is to quickly notice when these attitudes creep in during periods of increased vulnerability or when we encounter a particular client or type of client that elicits such sentiments. And most importantly, it’s a matter of what we choose to do about it. Such experiences are ideally gut-check times and a call for supervisory guidance. It is in this process of self-inventory and professional guidance that we can rise above our own defensive reactions and authentically connect with and care for those we are pledged to serve.

The open wounds of the men and women seeking sanctuary within addiction treatment and recovery support settings offer the potential for life-transforming encounters. What the wounded need in such moments are not just our technologies, but our humanity–not just counseling technique, but the kind of empathy and compassion that transcend the roles of the helper and the helped. We call that love.

Reggie Warren woke up one day and decided he’d had it with using drugs. After years of addiction and the problems it caused in his life and his family, he went to treatment and found solutions. One of the solutions that made the most sense was SMART Recovery because it helped him take a good hard look at the things and people the he most valued in life and how important it was to keep them. Listen to Reggie’s amazing story now!

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

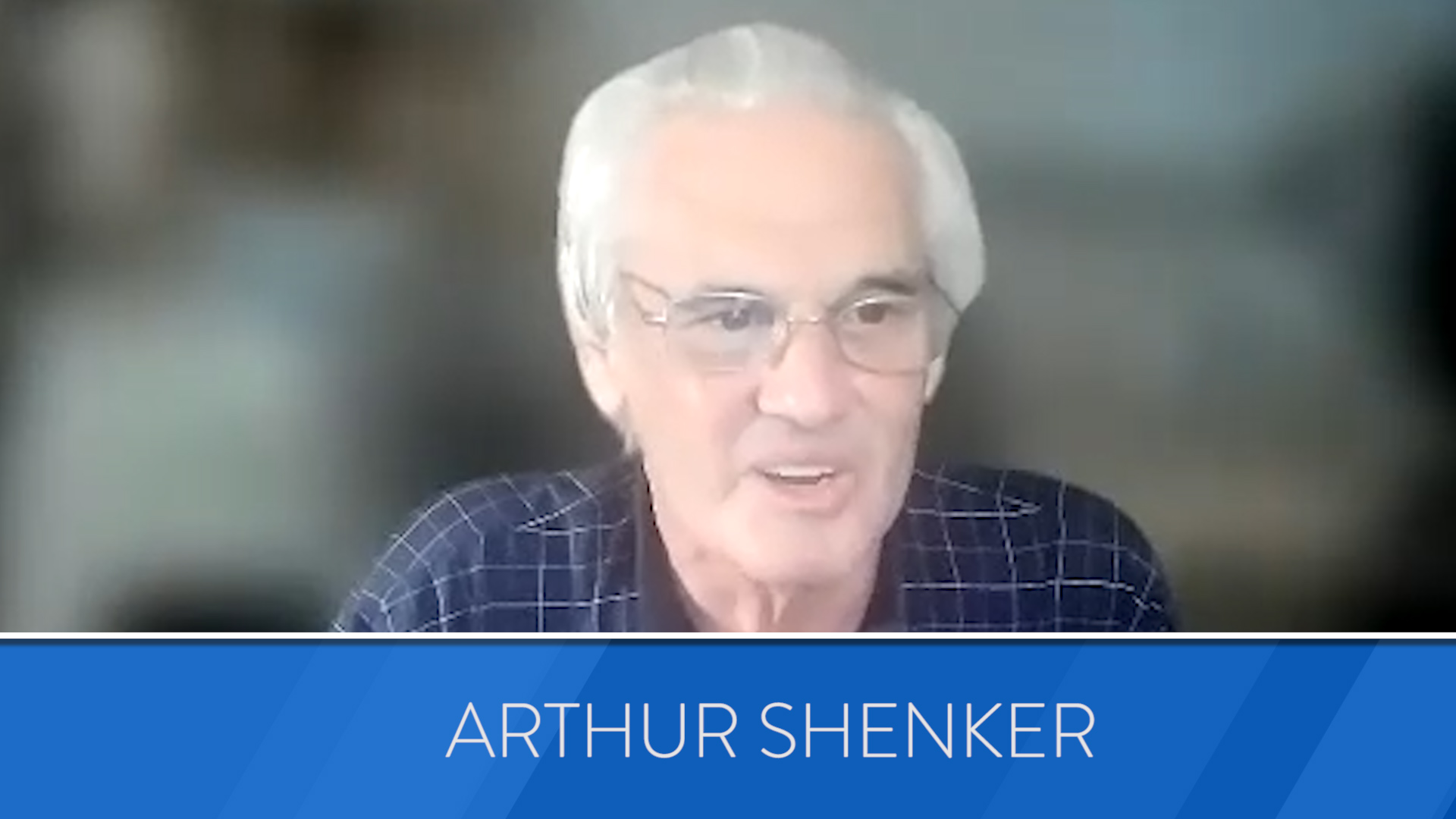

Arthur Shenker has used SMART Recovery in his own recovery journey and now facilitates several meetings to help countless others. He has proven to be an indispensable asset to SMART as he continues his successful to efforts to introduce the SMART Recovery program to more treatment facilities. THANK YOU, Arthur, for everything you do for SMART!

Learn more about becoming a SMART volunteer.

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Doug has been deeply involved with SMART Recovery for nine years. He applies SMART to his work in the Colorado Courts & Corrections environment, specifically the state’s drug courts. Doug is also a SMART Recovery regional coordinator who guides other SMART facilitators in their fine work. THANK YOU, Doug, for all that you do for the SMART Recovery community, and the help you give the people of Colorado to lead Life Beyond Addiction!

Learn more about becoming a SMART volunteer.

25 in 25 Volunteer Spotlight: Doug Hanshaw

InsideOut: A SMART Recovery Correctional Program® – For Prison Inmates

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Forward: I have met Phil Valentine a few times over the years. However, this was the first time I had a chance to sit down and have a direct conversation with him. Most of what I know about his work has come from hearing about how instrumental his ideas were to the development of peer services and reading his work. The thing that came through this interview for me most clearly is that Phil has a deep sense of what I see as the custodial nature of the work. He is not looking to be a rock star of recovery. He is following a path of purpose and the rich history of recovery bestowed on us in order to better serve the community.

There were themes that are emerging from this interview series for me; the importance of centering our work on recovery values, keeping recovery as the first priority, inclusion while maintaining a sense of humility and purpose. An observation I have made in life is that groups can have great influence over individual members, for better or worse. It is fairly clear that the group that formed out of this summit inspired each other to go out to do even greater things. This is the synergistic energy that can happen when recovering people come together and focus on principled action for a larger cause. Such dynamics can and often are replicated when such groups form and nurture each other.

An accomplished author, trainer and presenter, Phil has gained recognition as a strong leader in the recovery community; in 2006 the Johnson Institute recognized his efforts with an America Honors Recovery award. In 2008, Faces and Voices of Recovery honored CCAR with the first Joel Hernandez Voice of the Recovery Community Award as the outstanding recovery community organization in the country. In 2009, the Hartford Business Journal named him the Non-Profit Executive of the Year. He appears in the documentary “The Anonymous People,” a ground-breaking video that CCAR had the privilege of supporting. In 2015, Phil completed a thru hike of the Appalachian Trail, a journey of 2,189 miles, carrying the message of recovery the entire way (#AT4Recovery).

Other Recovery Community Organizations consistently seek Phil’s experience and expertise on a variety of topics – RCO development, Recovery Community Center development, peer recovery support services, recovery coaching, advocacy and others. Numerous authors have also sought his expertise including Bill White, Christopher Kennedy-Lawford, Dr. John Kelly, Bud Mikhitarian and Melissa Killeen.

- Who are you and what brought you to St Paul at that time?

My name is Phil Valentine, and I am the Executive Director of the Connecticut Community for Addiction Recovery (CCAR). I have been in recovery since December 28th, 1987. I had not been with CCAR very long before the 2001 Recovery Summit in Saint Paul. I came to CCAR in January 1999, about 2 ½ years prior to the summit. Before CCAR, I held a variety of jobs, including golf pro and insurance sales, but had not found purpose in these pursuits. The work of recovery support was where I found my purpose. I was just getting on my feet when we got an invitation to attend the recovery summit, and I went. We got the invite because we had one of the first Recovery Community Support Program (RCSP) grants awarded through SAMHSA. We were part of the vanguard, as Bill White says. I had not actually met many of the people in attendance. This was the first time we had all been face to face with each other in the same room.

- Is there a particular moment or memory that stands out to you from that summit?

I have a few memories. As I mentioned, this was the first time we had all been together. I heard someone else describe a powerful experience once by saying, “I do not remember what they said, but I know how they made me feel.” This describes my recollection of getting to the summit and meeting everyone. I felt included. I felt that we were all there for a common purpose. I had a deep awareness of a spiritual presence that is hard to convey in words. I remember talking with Bill White for the first time in person and a sense of being a part of something that had deep meaning. It was powerful. It stuck with me more as a feeling than any specific recollection.

I recall listening to Senator Wellstone and Congressman Ramstad for the first time. I had never heard anyone in positions like theirs being so supportive of recovery. They came out for us. Congressman Ramstad was open about his recovery. I had not really heard anyone do anything like that before. It was a wow moment. Up until then, recovery was pretty much in church basements, there was a chasm between those basements and the main congregation. This was my first glimpse that things could be different. I vaguely recall that Dick Van Dyke gave an interview on the Dick Cavett show in 1974, but mostly, such open dialogue about recovery just did not happen. This was a moment that resonated with me. I think many of us realized that something was happening, and we felt what the world might be like when people no longer had to live in the shadows. We experienced dignity, respect and embraced a deep belief that people who recovered from a substance use disorder would contribute in unforeseen, yet powerful, ways to the betterment of society.

- What did you see as the motivating factors that brought you all together for that historic summit twenty years ago?

I think we all felt in our hearts that there needed to be a coming together. We needed to connect and give voice to the healing power of recovery in our own lives, within the communities we live and build upon these experiences. I mentioned earlier that feeling of not being alone, of being a part of something, it was palpable. We wanted to put a face on recovery. We felt a conviction to work to normalize recovery. I think we recognized that it was vital for us to stand up and be out in the open and to live out loud in recovery. Without that, we would not be able to move out of a world where stigma kept us behind a cloak of shame. We did not want to live that way, recovery is beautiful, not shameful.

We had purpose in our lives and the summit crystalized this for many of us, I know that is what happened for me. There was a growing sense within me that I needed to focus on the development of recovery coaching and bringing the power of lived experience into focus as a way to save and restore lives. I recall one time a person close to me talked about the value in seeing gaps and needs around them and the things that needed to change in order to foster improvements. They told me it is one thing to see those gaps and recognize those needs, but it takes a lot of courage to walk through those doors and into the unknown. We were giving each other permission through our collective strength to open those doors and step through them.

A lot of our focus was on recovery support services and the need to develop services that would occur before, during, after and, at times, in lieu of formal treatment. I want to emphasis that we knew in 2001 that recovery support needed to be its own area of focus and not an appendage of treatment. The analogy I would make is this: A family member of mine suffered a knee injury while playing soccer and he needed care. It started with surgery – someone needed to go in and repair the damage inside his knee. He was not all healed up and ready to walk at that point, he also required physical therapy. He needed to exercise and develop the strength and practice movements in a way that would allow him to regain a full range of function. Addiction treatment is like surgery, and recovery support is like physical therapy. The recovery coach walks with you and helps you regain your feet and get on your path. The recovery coach is the physical therapist, not the surgeon. They are different specialties.

Recovery coaching is an area of specialty and one that came from us and must remain ours and not be appropriated or colonized by clinical care entities. What was true then is no less true today; that recovery support cannot become clinically based. The heart and soul of recovery support is lived recovery experience and the support provided to help others regain their lives through the establishment of hope, purpose, and connection. This has been my life’s work, as it has been the life work of others who have found similar purpose.

- How have we done in accomplishing those early goals?

This is a big question! It is hard for me to see back through the barrier of time. We had a notion of building a national grassroots organization. We knew we needed a place for us to get together and for the magic to happen. There is something special that can occur when recovering people get to together and really celebrate the deep connections we share. The summit brought us all together in some profoundly powerful ways. This was in itself an accomplishment. We all felt it. There was a spiritual ripple that emanated out of that gathering. Small waves at first, growing in concentric circles and gaining momentum, which then moved outward from that summit in the middle of the country, and out across the nation. There was excitement, enthusiasm and energy we gained from each other. Recovery community, in itself, is a power greater than ourselves when we come together in ways that affirm our values and allow us to see, hear and understand each other. This is powerful stuff, and I suspect many readers in recovery will recognize similar moments in their own lives when one encounters a group of people in recovery who accepts you, has similar experiences and who sees, respects and values individual difference.

- What do you see our greatest successes to date are?

I think our greatest success was the recognition of multiple pathways of recovery. I’m reminded of Bill White’s words “There are multiple pathways of recovery and all are cause for celebration”. We began to understand that then and I think history served to validate that concept. In that era, many people who followed 12-Step recovery had never met anyone who had on a different journey of recovery. The summit changed all of that. Intentionally, we built recovery connections and changed perceptions. As an example, I remember we talked about medication assisted recovery. We wanted people to no longer be ridiculed or feel that somehow, they were less than. That was so important.

12-Step pathways are still the most prevalent, but we now have a community that is much more diverse in recovery experience as a result of the effort put forth to validate other pathways. I’ve often heard in 12-Step meetings, “No one has ever come back and told us it’s better out there.” The inference is that people leave 12-Step meeting, return to use, then come back to meetings with their tail between their legs. I’ve always wondered about that; I’ve questioned authority for a long time. I reasoned if someone no longer attended meetings and their life remained good and/or improved, why would they come back to a meeting and tell us?

Through my work at CCAR, I entertained a growing recognition that my specific pathway was not the only way. And I found people who found recovery in different ways than mine. And as I have matured in my recovery, I have found that I no longer have to defend my pathway as the correct one. The coming together of the recovery community that started at the summit helped to create a space to intentionally listen for, recognize and value other pathways. That is a success we need to own and build upon moving forward.

- What did we miss if anything looking back at those goals?

I think we missed the opportunity to bring people together more fully and more regularly. We could have brought people together in ways that created a stronger foundation and common purpose on an even deeper level than what we accomplished. If somebody put me in charge for a day this would be something I would focus on – bringing people together more frequently and with intention to understand differences, seek common ground and build a solid organizational foundation on that ground, together. It’s not too late to start that now.

Concurrently, I believe deep benefits would result from creating a space for sharing what is working, comparing challenges and shifting perspectives. Innovative collaboration would mold our collective experiences and insights into something more than the individual pieces. We could move from conceptual framework into an operationalized, comprehensive model of recovery care and support. We have made progress in these areas, but we would have benefited then as we would now in creating such a space. I do not mean something like a standard conference. I am talking about more of an organic listening and mutual learning space where there are no agendas other than building out a model of recovery management for us, and by us, set up in ways that do not lead to the co-optation of our work and our practice space by outside interest groups.

In 2007, Pat Taylor, Bill White and I wrote “The Recovery Community Organization: Toward A Working Definition and Description.” People have used those concepts to frame out recovery community organizations, but even back then, there was movement to take this concept and dilute them into the treatment space as ancillary structures centered on treatment. I’ve also written about recovery community centers and I have found the effective recovery support is centered on community. Funding and focus will move away from our common purpose unless we define and build out services centered on the recovery community. We can only accomplish this by bringing us all together. Deeper connection builds this common identity, the development of recovery-oriented care and organizational structures centered around our common needs. When we do not collectively strive for this, we end up in a trap where we compete against each other and get redefined by outside interests. It harms us all.

- What are you most concerned about in respect to the future?

Frankly, I don’t worry. My sense is that the best is yet to come! My recovery is rooted in faith. Recovery is a whole lot like water in that it flows around obstacles. I think of a quote by Jeff Goldblum in Jurassic Park, he said “life always finds a way.” Recovery is like that. Recovery will always find a way despite any obstacle. It is not going away; it simply flows around the obstacle. Even though, I believe the spiritual nature of recovery is unstoppable, I do believe human beings have things to pay attention to. There is an ever-present temptation to make recovery support a clinical experience. I feel this is a mistake, and it will severely limit the potential of recovery support services if we allow things to continue to move in that direction.

Even if that happens, history shows us recovery will rise again. With that being said, my concern is that if we allow our work to be co-opted, a lot of lives will be destroyed. Many, many more lives will be redeemed if we stay on the path of building recovery support services nestled in community. There are always efforts to put limits on things, to create barriers, to professionalize peer services and to divide us up. For example, we now have family peer services. What is next? How many derivatives and variations of lived experience will we end up creating? They end up separating our focus. Good recovery coaching is good recovery coaching, and we need to just stop all the fragmentation and building bureaucracy…. I wish we could just stop it, but money always comes with restrictions, and temptation.

- What would you say to future generations of recovery advocates about what we did and what to be cautious of / your wishes for them moving forward?

I was just talking about this at a staff meeting. I am going to start to sound like Don Coyhis here, as I am about to make a tree analogy. I see a healthy recovery community organizational structure in the imagery of a healthy tree. A tree needs deep roots and that is the administration of an RCO; the administration is the foundation on which an RCO is built. This creates the stability needed and supplies vital nutrients to the rest of the tree. The soils (and Don talks a lot about the soil) is the organizational culture. A positive, nurturing, supportive, encouraging culture makes the best soil. The trunk of the tree is the leadership, and it is dependent on the support of the roots (administration) grounded in the soil (culture).. A strong trunk, tied to a deep root system supports the branches. In other words, bears the weight of the rest of the tree/organization. The branches are often recovery coaching and recovery support that help people obtain and sustain recovery. This is the fruit that grows on these branches. All parts of the tree have specific roles, none more important than another.

When we think about ambition, we often think about climbing a career ladder into management and administration. I know I have at times in my life. One can lose touch with one’s own roots when in pursuit of personal gain. There is a paradox here. I reached a point in my own recovery and in my own life when I realized all the material stuff, the car, the house the toys did not resonate with me in ways that kept me fulfilled. Very early in my recovery, a quote from Bill Wilson, founder of AA, changed my life; “True ambition is not what we thought it was. True ambition is the deep desire to live usefully and walk humbly under the grace of God.” When I pursued “living usefully”; I discovered meaning and purpose. I found I was to simply carry the message of recovery. Shortly after this discovery, CCAR found me. When I through hiked the Appalachian trail in 2015 and invested time in my own self-growth, my purpose became more refined. I now believe I am at my best when I “coach recovery”.

I would tell future leaders to walk humbly and to focus on recovery first. The services and roles we have are distant priorities to promoting recovery first. We must be cautious of self-promotion and pursuit of worldly stuff that ultimately carries less meaning and can be erosive and destructive. Focus on promoting recovery, growing in recovery and helping others.

This is critical; if we stay focused on recovery first, there are no limits to what we can and will do. I am looking forward to seeing what future advocates build. I am an optimist because recovery always leads us back to health and healing at all levels, individual, family, and community. We are part of a larger process, linked intergenerationally through history. When we center on recovery, everything else gets better too.

Finally, I would tell them to follow the light within themselves, it will illuminate the world.

A version of this post was originally published in November 2019.

In recent years it’s become more and more common to see advocates criticize treatment and mutual aid groups. These critics question the alleged orthodoxy and motives of treatment providers, but they do not engage in criticism of medication-assisted treatment (MAT). It appears that this would be perceived as punching down, despite the fact that it’s big business, aligned with powerful interests, and has benefited from massive federal investment.

A few weeks back, Bill White posted a new paper, From Bias to Balance: Further Reflections on Addiction Treatment Medications.

Bill’s been a forceful and effective MAT advocate for decades. He has worked hard to advocate for MAT providers and patients AND challenge providers to acknowledge and address their shortcomings. (It’s worth noting that he forcefully challenges other treatment providers in exactly the same way.)

He calls upon advocates to avoid “replacing a mindless anti-medication bias with an equally mindless pro-medication bias” and acknowledges that there are legitimate concerns behind resistance to MAT.

High treatment attrition, combined with the lack of psychosocial support during and following medication maintenance, contributes to the high addiction recurrence and mortality rates following medication cessation—death rates as high as four times that of patients remaining in treatment (Zanis & Woody, 1998; Sordo, et al., 2017). Public and professional perception of such high morbidity and mortality rates contribute to the negative perception of the long-term value of medication as a treatment for opioid addiction. The resulting bias against medication is not a product of public, professional, or patient ignorance, but results from fundamental design flaws in the pharmacotherapy of opioid addiction. If more positive attitudes toward medication support for recovery from opioid addiction are to be achieved, it will require enhanced strategies of treatment engagement and retention; amplified psychosocial supports to enhance medication adherence, global health, and social functioning (particularly for those with the most severe, complex and chronic disorders and for those choosing to taper off medication); and assertive monitoring and support following cessation of medication maintenance. (See White & Torres, 2010). It is important to disentangle one’s views about a medication from the clinical structures within which that medication is delivered.

From Bias to Balance: Further Reflections on Addiction Treatment Medications

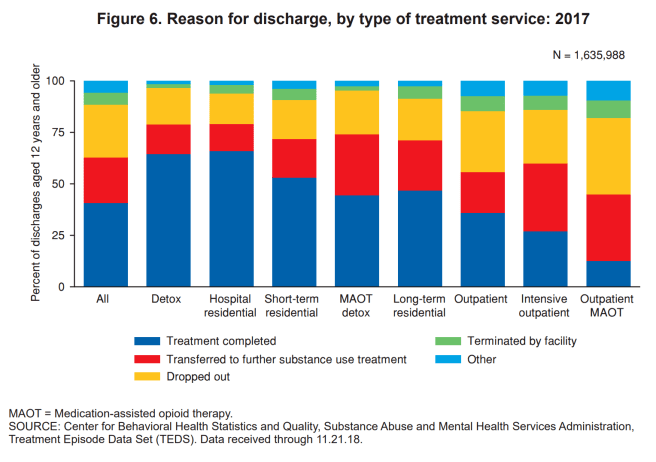

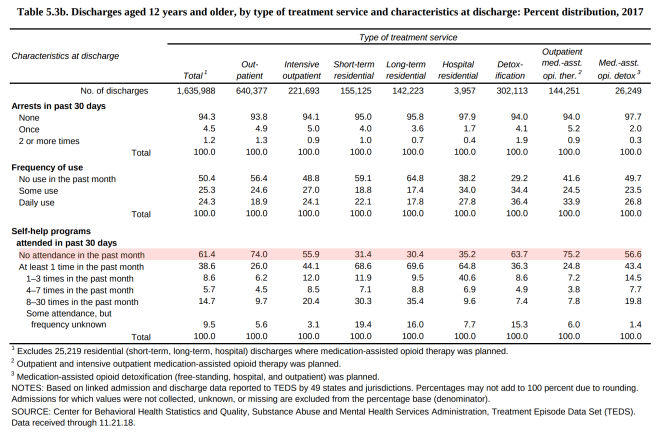

A recent SAMHSA report illustrates the retention problem Bill references.

The same report also illustrates the lack of psychosocial support at discharge.

Unfortunately the provider response to disappointing retention rates has been to strip away psycho-social-spiritual elements as though they interfere with access and retention to the real treatment—the medication.

Lowering the engagement threshold is a very worthy goal, but that should be a starting point rather than an end. It should be approached as an opportunity for the system to provide the kind of recovery-oriented amplified support that Bill describes above. He ends the paper with a call for better MAT that positions medication as one element of a comprehensive bio-psycho-social-spiritual treatment plan.

Medications are best viewed as an integral component of the recovery support menu rather than being THE menu, and their value will depend as much on the quality of the milieus in which they are delivered as any innate healing properties that they possess. If the effectiveness of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) programs is compromised by low retention rates, low rates of post-med. recovery support services, and high rates of post-medication addiction recurrence, as this review suggests, then why are we as recovery advocates not collaborating with MAT patients, their families, and MAT clinicians and program administrators to change these conditions?

People seeking recovery from opioid use disorders and their families are in desperate need of science-grounded, experience-informed, and balanced information on treatment and recovery support options—information free from the taint of ideological, institutional, or financial self-interest. In an ideal world, recovery advocates would be a trustworthy source of such information.

From Bias to Balance: Further Reflections on Addiction Treatment Medications

Probably the biggest gift Bill gives to the field is the willingness to model assuming positive intent and seeking to understand the point of view of others.

For example, there is a bill pending in Pennsylvania that would require counselling accompany treatment with medication. The reaction has been swift and strong. However, it is possible to maintain the conviction that the bill is a terrible idea AND hold space for it as a well-intentioned response to serious, neglected, legitimate problems. With that in mind, I’ll leave you with this.

There is limited long-term value in replacing a mindless anti-medication bias with an equally mindless pro-medication bias. The challenge for recovery advocates is to forge a source of reliable information between the extremes of “Never” among the rabid medication haters and “Always and Forever” among the most passionate medication advocates. In our efforts to promote the legitimacy of multiple pathways of recovery—including medication-supported recovery, we need far more nuanced discussions of the potential value, the limitations, and the possible contraindications of medications across the stages of recovery.

From Bias to Balance: Further Reflections on Addiction Treatment Medications

Take the time to read Bill’s entire paper and the post he uses to introduce it.