Chuck Novak’s life hasn’t always been easy. A substance use problem led to five years in prison. While incarcerated, Chuck decided to use his time to change his life for the better. He earned a paralegal certificate and started on a path to recovery. Today, Chuck is a Master Licensed Drug and Alcohol Counselor and a SMART Recovery Regional Coordinator in New Hampshire.

In the podcast, Chuck talks about:

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Barry Grant’s experiences being incarcerated over 20 years ago changed and shaped his future forever. Today, Barry is the owner of S.A.F.E Counseling Services, Director of Outpatient Services at Hope House, and SMART board member. His tireless championing of the SMART program has helped countless people in their recovery journey.

In this podcast, Barry talks about:

- His history of being incarcerated and finding SMART while in prison

- Using his time in prison as an opportunity to grow and share experiences with others

- SMART being in the here and now, not the past

- Examining and evaluating the human experience

- His meaning of recovery

- Choosing your behavior means choosing your consequences

- Becoming an autodidactic counselor

- The difference between being ready and being prepared

- Changing the vocabulary for incarcerated people

- How SMART principles are applicable to life situations

- Asking “Who Are You?”

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Forward: I first met Dona as she got PRO-A off the ground in those early years of the recovery movement here in Pennsylvania. PRO-A was one of the first statewide Recovery Community Organizations (RCOs) in the nation. I don’t even think I had heard of an RCO before I met Dona. She has had a huge influence on the recovery movement, both here in Pennsylvania and across the US. I think she would be the first to acknowledge that the things she has accomplished in her recovery are remarkable. She would also agree that such amazing stories are unremarkable in the recovery community. Recovery is the contagion of hope that saves and transforms lives.

Through her efforts in those early days, we had the first recovery rally in the rotunda of the Pennsylvania state capitol. I was there and it was empowering. We did not have to keep our recovery cloaked in darkness, we could talk about it in the seat of our own state government. It was organized by PRO-A along with other organizations. I recall those early years and efforts to get people to understand that anonymity was important, but it was not something that should limit our ability to stand up and advocate for people to get what we have had an opportunity to have, a life.

She has changed jobs and has held many titles over her career, but she has always placed the needs of our community in the center of her efforts. That has been inspirational to me. Dona has led by example by staying true to those same values. My life has been greatly enriched through her work as a recovery pioneer, as have the lives of so many other people across America. She made the time to do this interview with me late on a Monday night, after a long day, and I am certain she did so as she was putting the values of service first, something that has personified her efforts over the years. She walks the talk.

- Who are you and what brought you to St Paul at that time?

My name is Dona Dmitrovic. I am a family member impacted by addiction, a mother of one and a grandmother of four. I am a woman in long term recovery for over 35 years. Currently I serve as the Director of the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention for SAMHSA to support federal efforts to improve the nation’s behavioral health through evidence-based prevention approaches. Prior to SAMHSA, I lead the Foundation for Recovery in Las Vegas, NV. I assisted with the growth of FFR into a statewide recovery community organization offering peer services, education and training and advocacy for those in and seeking recovery. I served in several roles prior to that, including the Director of the National Office of Consumer Affairs for Optum Behavioral Health in Minnesota and COO of the RASE Project with the (Recovery – Advocacy – Service –Empowerment) project. It started as one of the regional groups associated with the PRO-A office. There I assisted the CEO and maintained relationships with policy makers, physicians, providers, and other community-based programs and helped launch the Buprenorphine Coordinator program. This program served opioid dependent individuals with recovery support services in Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT)- one of the first in the country offering this type of support and was recognized with two national awards for innovation.

Thinking back to the 2001 recovery summit in Saint Paul. At the time of the summit, I was the first Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Recovery Organizations – Alliance (PRO-A). PRO-A was founded in 1998. We learned of the 2001 summit during our connection to the Recovery Community Support Program (first grantee cohort) funded through SAMHSA. As part of that grant, we had regular meetings with all of the recipients from across the nation. It was the first time we had such a space for all of us to support each other along with federal representatives. Rick Sampson and June Gertig were two people that I remember as supporting our efforts. I think it was empowering for all of us. Cathy Nugent was our grant officer and through these meetings we learned about the recovery summit. We were encouraged to go. There were people from all around the country who attended. I recall a number of people who attended, including people from PRO-ACT in Philadelphia and Easy Does It in Berks County. It was the first-time people in the recovery movement from around the country had come together as one. There were people who had funded recovery community organizations as well as people who were just volunteering in their communities to support recovery efforts. That we all had an opportunity to meet and unite was historic. It was unprecedented, it had never happened before that moment.

- Is there a particular moment or memory that stands out to you from that summit?

I have a similar memory to Carol McDaid from her interview with you. It was when US Congressman Jim Ramstad and US Senator Paul Wellstone addressed the attendees. Here were two members of Congress standing up and talking about the importance of advocating for recovery. They got up to the podium and openly talked about the legitimacy of recovery and about the need for parity in care for persons with substance use disorders. We had never seen anything like that before. They gave us a sense of dignity and worth, a sense that our voices mattered. It made it okay for us to speak out too. If they could advocate for us, we could advocate for ourselves and our communities. It was a wow moment. It had an impact on me, I think it had an impact on all of us.

- What did you see as the motivating factors that brought you all together for that historic summit twenty years ago?

I think it is important to recognize the role that SAMHSA had in it, they helped connect us through those RCSP grants. It is also important to realize that many of us had advocated for the creation of those grants as well. It was a time when a lot of forces that ultimately culminated in the summit. There was a lot of support coming out of DC that helped make the vision a reality. The Legal Action Center helped, as did the Johnson Institute. They committed time and energy to the summit. The timing was right. We were all coming together, and we were starting to realize we had to speak in one voice. I don’t think I can overstate the importance of bringing us all together in that moment. We knew we needed a national advocacy organization that was run by us and for us. We needed a way to represent ourselves and protect persons from discrimination and to give voice to the needs of our community.

There is history here. While there were organizations like the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, which was founded by Marty Mann in 1944, there is a tendency over time for organizations to move more into a service focus and become less oriented on advocating for the larger needs of persons in recovery and against the discrimination we face. It was doing good work, but we knew we needed an organization that was centrally focused on bring our recovery voices together in ways that centered our efforts and made sure our interests were being represented. We had seen what happened to the Society of Americans for Recovery (SOAR). We became really motivated to make it a reality and I think there was widespread recognition that developing a constituency of consequence around recovery was vitally important.

Bill White was integral to our efforts; he was like our glue. I am not sure where he came from, but he had wonderful ideas, and we coalesced around them. I think it is important to understand how important he was in what happened. He was not exactly our leader, but he had ideas and he shared them in ways that really highlighted the values of recovery. We listened to him because what he had to say resonated with us. He avoided ego and spoke of all the pitfalls we have faced when recovery movements have historically become centered on a single leader. When he spoke, everyone felt motivated and there was a sense of being part of something larger than each of us on our own. He helped instill those values and the leadership from a place of humility that is vital to our efforts. I think that you and Bill recently wrote about being recovery custodians and not falling victim to ego and ambition. It is what has killed every prior recovery movement. He helped us stay centered and focused on building something bigger than any of us on our own could individually accomplish.

- How have we done in accomplishing those early goals?

We have come a long way since that summit in 2001. We still have a long way to go. As Bill White recalled in his 2013, State of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement presentation, we developed goals and worked hard on them. Bill rightfully called attention to the risks that our efforts get derailed, either as a result of our own actions or external forces. But we have done a lot of positive things. One area that comes to mind is the development of recovery focused research. We are seeing this emerge, but it takes a long time for systems and institutions to reorient and focus on new ways of thinking about, measuring recovery services in ways that demonstrate the value they offer. We are seeing recovery focused research, but we have a long way to go before we move recovery as an orientation fully grounded in evidence. It takes time to develop this body of literature. It was a focus from those early days, we knew we needed it, efforts to measure it are coming together.

I think that another one of the major accomplishments was the focus on many pathways to recovery. We emphasized that we should not dismiss any other person’s pathway to recovery. We included family in our focus, which was also revolutionary. Huge gains have been made in this area. We now value all pathways and uphold the importance of individuals, families, and communities to pursue their fullest capacity to live and be the most they can through their own recovery processes.

We also have learned along the way that we need to be careful. There are times we stood people up too soon and put them in the limelight to share their messages publicly. Sometimes we did this before they had done work on all of the underlying trauma and before they had gone through the process of healing they needed to undergo. We did not mean to harm them, but we lost sight of their needs in the pursuit of some gain we saw as important at that moment in time. We must remember not to do this. It can be very damaging. We need to keep this lesson always at the forefront that we must focus on recovery and tak care of ourselves first. We must resist the temptation to put others in positions where their recovery is at risk for some goal or objective. When we do this, we undermine our own movement.

I think we have done a good job at educating policymakers by sharing our stories with them. This may be the most important thing we accomplished. It also helped policy makers to share their own stories, something that was not possible for them to do before our efforts to legitimize recovery. They also have personal and family experiences with addiction, and our efforts allowed them to be open about their own life experiences as well. It put us all on equal ground as it has really become apparent that everyone in America has been impacted by addiction. “Those people” are really “our people.” We no longer had to hide in the shadows in guilt and shame. The summit brought us together. It helped us see our commonality and to understand how we had so very much more in common than any minor differences we have.

- What do you see our greatest successes to date are?

It is impossible to overstate the value that came out of bringing us all together to form a unified community. We honored all pathways of recovery in ways that people saw each other’s value. We emphasized that whatever pathway any one of us used was not the only way, it was only our way. All of the pathways are to be valued. By listening to each other, we learned about each other in ways that helped us all see and appreciate the legitimacy of all pathways. We developed mutual regard and respect. This was a result of us coming together and spending time with each other and working towards common goals. It is true at least in the recovery advocacy realm that all pathways are embraced, and this came out of that process of being together. Similar dynamics have occurred in respect to the commonality with the mental health community. We have come a long way, we have a long way to go, but we must understand and celebrate what this first summit set in motion, it brought us all together, focused on common purpose.

- What did we miss if anything looking back at those goals?

We need to learn from our own history. It is important that our message stays unified. That message may change over time, but history shows us how important it is that we do not become divided up in factions. This is destructive to our common purpose. Recovery is life saving and life defining process for persons, and when we get our lives together, we can do amazing things. Recovery is life affirming. We have shared values. We have a shared identity. Recovery has many pathways and forms, but the inclusion of all of these facets are central to our common welfare. I am not sure we have focused enough on bringing people together in ways that magnifies our common cause as well as we should have. It is in the coming together and listening to each other that are common identity is strengthened. I think we have missed opportunities to do this along the way. It takes time and energy to create space for people to listen to each other, but it is vital that we always do so.

What can happen is we get focused on a particular service or on furthering individual ideologies and we fracture and lose ground over time. It is not too late to change any of those dynamics. When we come together in a unified way and put our individual agendas and our differences aside, we all do better. History is clear on this. People like Bill White have kept reminding us of these dynamics, we have not always listened. We do better when we pay attention to these repeated patterns that are so evident from our own history.

- What are you most concerned about in respect to the future?

We have to heed own history. If you want to understand the things we want to accomplish moving forward, we have to understand our own history. We have to consider what has happened to recovery movements that have come before us and look at what has happened to institutions focused on our issues over the long term.

How do we learn from our own history to ensure we get to where we want to go? How do we stay focused on a common mission that does not get redirected by individual agendas or mission creep? How do ensure inclusion so that our foundational institutions continually reflect the needs of our own community? There is a pendulum of history we need to pay attention to. It becomes a matter of dispensing with individual agendas and understanding that if you are doing this work, people are watching you. People look up to us, and we must always model recovery values in everything we do. That can be hard, but when we do so we achieve great things. And at the end of the day, we are all working towards this common goal … making recovery possible for individuals and families and ensuring that death is not the outcome for those with substance use disorders.

- What would you say to future generations of recovery advocates about what we did and what to be cautious of / your wishes for them moving forward?

I would tell young recovery leaders to stay in touch with their passion, it is the thing that sustains us. I know this is what has kept me going. I suspect that this is true for others as well. The truth is that if you are a recovery advocate, you are going to get knocked down a whole lot more times than you will be lifted up. I would tell future leaders that they should stay in touch with why they do this work. I think for many of us, we want to make sure that others who come after us have the opportunities we have had in our own lives. We are working towards something greater than each of us as individuals, increasing access to help, supporting an individual’s pathway to recovery and developing the resources to sustain recovery for all of our communities, in all of their respective diversity. We can only do so when we take care of ourselves and nurture our own recovery and stay true to recovery values and keep moving forward. If the next generation builds the foundation on recovery values like service, integrity, empathy and inclusion, they will accomplish great things and I see that happening right now. They will make history.

Last week a book I had ordered dropped through the letterbox. It’s Adam Hill’s ‘Long Walk Out of the Woods’. He’s a doctor who developed an alcohol use disorder and recovered from it. The book about his journey is next on my reading list.

The arrival of Adam’s book triggered thoughts of my own story and then of the colleagues in recovery I’ve got to know over the years. I have also been thinking of some who have died from their addiction. There is no doubt about it: doctors get addicted to alcohol and other drugs. We also get different treatment and better outcomes from that treatment compared to our patients. But what about nurses?

If you are a nurse or a doctor with a substance problem and it comes to the attention of your employer, then what happens to you in the UK really depends to a large extent on varying policies but also geographical and local political considerations, not to mention the approach of your regulatory body.

My impression is that doctors and nurses with substance use disorders often have different experiences in the UK when it comes to getting help and, although this is not scientific, I believe that, in general, doctors get a better deal here from employers than nurses.

Physicians & Nurses

I was reminded of a paper published a while back in the Journal of Advanced Nursing[1]. Matthew Shaw and his colleagues looked at this subject. Incidentally, one of the authors is Daniel Angres. I recommend his excellent book: Healing the Healer: the Addicted Physician.

The researchers wanted to compare the experiences of doctors and nurses when they first sought help, when they went through treatment and how well they got on after treatment was complete. They hoped that such interdisciplinary comparisons in healthcare would help to “identify the distinctive risks for the development and perpetuation of these [addictive] disorders, and the obstacles to successful recovery.”

The authors make the point that the literature suggests doctors and nurses are not any more at risk of addiction than the general population. What does mark us out is the nature of our addictions (after alcohol, prescription drug dependence is most common) and where we procure our drugs (the workplace). The implications of this for patients, themselves and their families are potentially great.

Theories

Some theories to be tested were set out:

- Doctors, often working alone rather than in teams, will present later and with more severe problems

- Nurses will participate in treatment better due to their working in more collaborative environments

- Nurses will experience harsher professional sanctions due to less empowerment and advocacy

How did they go about testing these? One hundred and ninety-two people enrolled in a treatment programme dedicated to healthcare professionals in the US between 1995 and 1997 were involved. There was no control group as it would have been unethical to deny treatment to any group (though it might have been interesting to have a control group of non-healthcare professionals going through similar treatment). Data were gathered from records retrospectively and from prospective interviews.

Questionnaires were sent out to potential participants and just over half were returned. The researchers tested for the possibility of selection bias by comparing the demographics of the non-responders and the responders. They seemed to have pretty similar characteristics. Of the 105 people agreeing to participate, there were 73 physicians and 17 nurses. These made up the study sample.

Differences

There were some differences between the groups at baseline. The proportion of females was higher in the nursing group. A higher percentage of nurses were divorced or gay. Relatively more doctors than nurses had personality problems, but the doctors were functioning slightly less well. Doctors tended to be referred to treatment by physician health programmes and nurses by their employers.

Substance use pattern differed significantly. For doctors, 30% used only alcohol, 28% used only opiates and 30% used alcohol and prescription opiates, whilst 65% of nurses relied on prescription opiates only. Nurses did not go for poly-drug use, with only three using more than one substance.

Recovery

There are plenty of interesting findings in the paper. What pushed the doctors and nurses to seek help? Was it breakdown of health or relationships? Was it legal issues or social disintegration? No, it was primarily because of work. Nurses and doctors rank their work over just about everything else, including emotional distress.

Both groups identified their participation in 12 step programmes as being important to their recovery, but nurses reported a greater reliance on fellowship with other people in recovery. At follow up, almost three quarters of both groups had active licenses to practise and nurses were working more hours than before recovery started and doctors less.

The rate at which nurses were placed on probation was not only higher than physicians prior to treatment, but was also disproportionately higher than doctors after treatment. Similarly, although nurses and physicians were equally likely to experience professional sanctions prior to treatment, nurses (53%) were more likely to be sanctioned after treatment than doctors (35%). In addition, nurses tended to be more distressed on multiple measures than doctors at follow up and the authors say that nurses work in situations with more triggers to relapse, though I didn’t see convincing evidence for this.

There are some obvious limitations to this paper, which the authors do acknowledge. The number and proportion of nurses makes robust comparisons difficult. Only fourteen percent of the doctors were female, but 82% of the nurses were meaning gender issues could be confounding. There was no control group of any kind and the data were all collected at a single site. These all limit generalisability though should not stifle debate.

Findings

And their hypotheses – do doctors have more problems at presentation? That supposition was supported by the data.

Do nurses engage more fully in treatment? Well in this study, doctors used more intensive support than nurses. The authors speculate that may be because doctors can afford to. Doctors reduced their working hours in recovery, but nurses increased them and there was this association with greater psychological distress. Again this may be explained by income differences.

And what about the third hypothesis: nurses will experience harsher professional sanctions due to less empowerment and advocacy? Sadly, this did seem to be supported with nurses getting a raw deal:

“Therefore, the group who can least afford to miss work appears to be most likely to be reprimanded and may be least likely to seek costly legal representation.”

An incidental finding came onto the radar. In this sample, 7% of doctors committed “sexual boundary violations” and 18% of the nurses were victims of violence. We need to view that with the lens of gender differences between the samples. This was worrying.

Of particular interest is that substance use outcomes were the same across doctors and nurses: all participants reported abstinence, although the doctors had higher average duration of abstinence than the nurses, which for me raises the question: can we expect better outcomes from the general population if they get access to the same sort of treatment that doctors normally get?

Imperatives

In concluding, the authors hope that these findings and others to follow: “can inform programmes developed to prevent substance use in medical environments, treat health care professionals once they become symptomatic, guide the advocacy work of professional organisations, and modify professional sanctions so as to be effective means of accountability, deterrence, and most importantly, recovery.”

Julie Worley, writing in the Journal of Psychosocial Nursing[2], reported that there are barriers to nurses getting substance use disorder treatment including ‘wide variability in Alternative to Discipline programmes, inconsistent funding for treatment, and lack of policies and support for nursing students.’ These same challenges face doctors, but overall I still think pathways to treatment, recovery and return to work are often easier for us.

The skills that become impaired in addicted healthcare professionals can flourish again in recovery and it is important that we are aware of the issue, can help identify it and support colleagues to seek treatment and recovery support. Stigma of course prevents many coming forward. There are more and more doctors opening up about their addiction stories in recent times which I think is immensely helpful in defeating stigma. I’m not so aware of the public narratives of nurses, but if you know of any, please post links below.

(This is an updated version of a blog from a while back.)

Continue the discussion @DocDavidM

[1] Shaw MF, McGovern MP, Angres DH, Rawal P. Physicians and nurses with substance use disorders. J Adv Nurs. 2004 Sep;47(5):561-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03133.x. PMID: 15312119.

[2] Worley J. Nurses With Substance Use Disorders: Where We Are and What Needs To Be Done. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2017 Dec 1;55(12):11-14. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20171113-02. PMID: 29194558.

This post was originally published January 1, 2020.

I’m not sure why, but I’ve been missing Roger Ebert recently. I’ve posted about him a few times before and commented on my appreciation that he was a film lover first and a film critic second.

I think it’s safe to say that social media has multiplied and elevated critics. I’ve been thinking about the role of critics in addiction treatment and recovery advocacy. I wondered this morning whether Ebert has anything to teach us.

We see an abundance of criticism of mutual aid groups, treatment providers, treatments, advocates, language, policy, media coverage, etc.

So, what should we make of criticism?

Ebert described the criticism of criticism this way:

Criticism is a destructive activity. … They think they know better than creators. They praise what they would have done, instead of what an artist has done.

He goes on to quote Anton Ego, the food critic from the film Ratatouille. Anton offers an important insight about the role of the critic. [emphasis mine]

“In many ways, the work of a critic is easy. We risk very little yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgment. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face, is that in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is more meaningful than our criticism designating it so. But there are times when a critic truly risks something, and that is in the discovery and defense of the new.

Of course, Ebert’s observations can only take us so far—art criticism is about the subjective. In addiction treatment and recovery, we all seek to occupy a much more objective space.

We seek to put everything in objective terms—policies, pathways and treatments, as well as the impact of things like language and media coverage. This is good. We all should want policies and practices that are fact-based.

However, I tend to think most critics in our field overestimate what we know (or can know) objectively. These critiques and arguments don’t feel subjective, but they are much less objective than often make them seem.

So … if we’re frequently operating outside of the objective, maybe Ebert has something to teach us about criticism worth doing.

Ebert meditates on the meaning of Anton’s statement and doesn’t agree completely. He questions whether the creation of “junk” is actually more meaningful than criticism of the junk.

He adds the following about criticism worth doing:

[the artist] discovered the new. A critic can defend it, publicize it, encourage it. Those are worth doing. … you must know why you like a film, and be able to explain why, so that others can learn from an opinion not their own. It is not important to be “right” or “wrong.” It is important to know why you hold an opinion, understand how it emerged from the universe of all your opinions, and help others to form their own opinions.

He seems to be saying that good criticism emanates not from interrogation of the subject (or target), but from interrogation of oneself. Further, good criticism encourages others to think for themselves rather than telling them what to think.

If you were asked to physically point to the location of a person’s addiction illness, where would you point?

My answer might surprise you.

- Where would you point if you were asked?

- Have you ever thought of that question?

I’ll share my answer to that question a little later in this essay.

But first, try to think of some ways someone could go about answering that question.

- One way to find or build an answer to that question would be to look at the addiction definition from the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). The current language from ASAM1 includes the idea ASAM has used elsewhere that “the public understanding and acceptance of addiction as a chronic brain disease and the possibility of remission and recovery have increased.” Based on that, one might naturally conclude that addiction is located inside the skull.

- Another way to build an answer would be to look at research from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). NIDA prioritized brain research in the 1990’s and called the 90’s the “Decade of the Brain”2. The results of that research and the resulting information campaign might leave one to think that addiction is located inside the skull.

A different way of knowing would be look, see, and say what you see.3

- Here’s an example of “look, see, say what you see”. In the history of scientific inquiries some things have been named how they simply looked.

- In the history of the study of human anatomy and physiology we learn that a that portion of the brain, when it was found and seen, looked blue.

- In Latin, “locus” means “place” or “location”. And “coeruleus” is a word that contains the root for the word blue (like “cerulean blue”).

- You might have heard of the brain structure we call the “locus coeruleus”; they named that portion of the brain the Latin for “blue place”.

Where would you look to see addiction illness? And if you looked, what would you say you saw?

After you looked and told us what you saw, what you said would have been based on where you looked.

This is a puzzle or a paradox. How so?

- You will already lead yourself to a certain answer simply by deciding where to look. Looking in a certain place or in a certain way naturally results in certain conclusions. ASAM and NIDA decided where they were going to look. And they found brain function.

I have previously covered the question “What IS Addiction?” here at Recovery Review. Two posts of mine discuss what addiction illness IS.

- One of those two posts centers on work Norm Hoffmann did in determining the relative weight that each of the DSM-5 SUD criteria separately contribute to the potential identification of addiction illness.

- The other post examines definitional expressions from ASAM and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)4 about “addiction”.

But in this current post, I do not ask what addiction is. Rather, I ask where addiction sits.

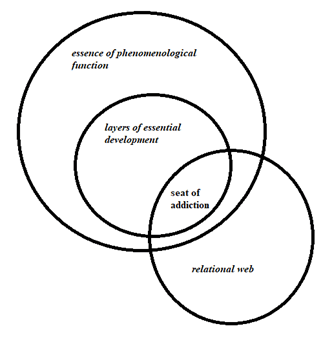

After 3 decades of looking at clinical work, if I was asked to point at where addiction illness is physically located, I would point to the nexus of the individual person’s social network (family, friend, neighbor, etc.).

That is to say, the seat of addiction illness is not merely inside the physical person of the one using substances, but is located in the centrality of their relevant relational web.

When I presented that idea in a recent conversation, I was challenged to locate the seat of addiction illness in the person5. Admittedly, I must say that the seat of addiction illness being inside the individual person is a real possibility. And thus, I need not unnecessarily complicate the matter with an irrelevancy. However, in my thinking, the example of such a phenomenon would be something like a castaway on a deserted island, out of human contact for decades, initiating substance use and developing addiction illness under those conditions. Possible? Yes. Commonly the case? No.

To be thorough and cover that contingency, I will add my perspective of what a person is. And overall that perspective includes two basic ideas:

- Bio-psycho-social-spiritual

- Developmental layers across the lifespan

What follows is my treatment of each.

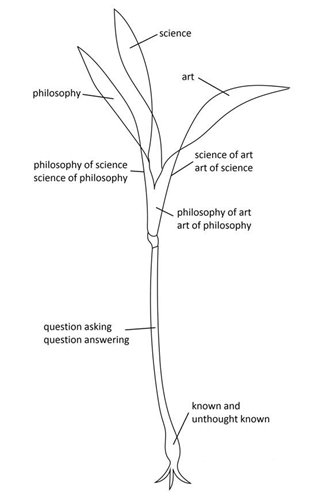

One of my favorite ways of thinking about a person as a total person is to use the phrase “bio, psycho, social, spiritual” as a reminder and starting place. And then, I often use either or both of two images to provide some details.

Here is the first image. After years of meditation, I decided that I could represent the essence of the phenomenological function of a person in the form of this diagram6:

For clarity and thoroughness I’ll say that I mean the words shown in that diagram in their simplest sense. For example:

- “science” could include any rational information gathering (e.g. a child turning over rocks in a tidal pool, or someone tracking the movement of stars), and

- “art” could include any craft on any level (e.g. a child using paint, or an adult practicing advanced metal work).

On the one hand, philosophy, science and art are products of considering; so in that way they could be thought of as petals produced by a flower. And on the other hand, philosophy, science and art are ways we take-in from the world around us; so in that way they could be thought of as the green leaves of the plant.

Generating questions, hypotheses, and answers to questions in life all seem central to the human experience. Meanwhile, much of what we know (that is either immediately accessible or even relatively out of access) seems to be stored below our level of conscious considering. And it seems that we take-in from the environment around us (e.g. soil, or other or deeper material, etc.) at this level too.7

In these ways, even though the plant does stand in a certain way relative to top/down or bottom/up as a whole, the parts of the plant are without superiority of being (is) or function (does) in terms of top or bottom. Both top and bottom result from the function of the other, and sustain the function of the other. And both result from and sustain the whole.

Is addiction located merely in the essence of the phenomenological function of a person? I don’t think so.

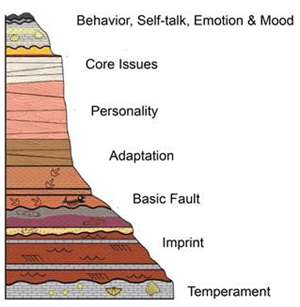

Here is the second image. After years of meditation, I decided that I could represent the layers of essential development of a person over their lifespan in the form of this diagram8:

Temperament is the closest to genetics. For example, shyness is irrespective of introversion and extraversion, and can be reliably identified in neonates just minutes out of the womb.

Imprint refers to life events from birth to around age 18.

Adaptations are the more primitive reflex patterns we regularly rely on to avoid or manage pain or stressors – either external or internal. They start showing up early in life and personality formation rests on the preceding adaptations.

Alas, the image is simplified and cannot properly show how some of these layers or their effects are more continuous across developmental stages. For example, our temperament never really leaves us.

Is addiction located merely in the layers of essential development of a person? I don’t think so.

Regardless of the bio-psycho-social-spiritual model, and of developmental layers and stages, when I look back out the rear windshield of my addiction career, I see that addiction illness is located in the nexus of interpersonal relations, differently, for each person.

Examples include the:

- seat of the family system

- relational web of street associates

- network of colleagues and work partners

It seems to me that addiction illness has its nexus or epicenter in the space of relationships, nested inside our developmental heritage, and the essence of what it is like to be ourselves.

I might change my mind or develop other ideas down the road, but right now this is how it looks to me.

And to the extent the idea of addiction illness being nested at the level of relationships is accurate, that makes me think about the word “connection” as it pertains to addiction. And it makes me wonder (in terms of actual location), “WHERE is recovery?”

Endnotes

1 ASAM definition of addiction; accessed 07/07/2021.

2 NIDA decade of the brain

3 Look, see, say what you see (cf. “Scout mindset” ala Julia Galef)

4 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. (DSM-5)

5 Personal communication with April Martin

6 “Unthought known” is borrowed from Christopher Bollas

7 “Facilitating environment” from Donald Winnicott was one muse for this image

8 “Basic fault” is borrowed from Michael Balint.

Suggested Reading

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945/1978/2014). Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge.

Hamilton, N. G. (1977/1999). Self and Others: Object Relations Theory in Practice. Jason Aronson, Inc.

Addiction doesn’t discriminate. Jamie Lee Curtis shares her recovery story.

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

It doesn’t come up much here, but I am a social worker. Both of my degrees are in social work, I’ve taught social work for the last 17 years, I’ve served on NASW’s Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drug Section, as well as NASW-Michigan’s Legislative and Social Policy Committee and Ethics Committee. This blog focuses on my work and thinking as an addiction professional, but social work is an important part of my professional life and identity.

I recently became aware of efforts to reduce NASW’s Code of Ethics’ emphasis on the value of service.

Here’s the relevant portion of the NASW Code of Ethics:

Value: Service

Ethical Principle: Social workers’ primary goal is to help people in need and to address social problems

Social workers elevate service to others above self-interest. Social workers draw on their knowledge, values, and skills to help people in need and to address social problems. Social workers are encouraged to volunteer some portion of their professional skills with no expectation of significant financial return (pro bono service).

The criticism of the value is as follows:

I had a strong reflexive reaction to this argument. I’ve always believed that the centrality this value is something that sets social work apart from other helping professions. (I could be wrong about that, but I checked the APA and ACA codes of ethics and couldn’t find any similar statement.)

As I reflected on this and asked myself why service is an important value that should be defended, I had a difficult time coming up with logical arguments. My reaction was more emotional than rational, but also still deeply held. (DBT has taught me not to dismiss my emotional mind, rather to seek synthesis with my rational mind to find wise mind.)

I vaguely recalled something entitled “In Praise of Service” but couldn’t find it. I did a little research and wasn’t finding anything that hit the spot, so I asked for help. It turns out “In Praise of Service” was a speech by Bill White in 1993.

In this speech he maps out the threats he sees facing the field — “rapid and turbulent change, competition and isolation, obsession with profit and regulatory compliance, technology over-extension”. The final threat he identifies is the profession’s pathologization of service as a value.

The final building block in this crisis of values within our field involves changing judgements about the role of service within the field. This has involved two related processes: narcissistic inversion and the pathologization of commitment to service.

The narcissistic inversion he refers to is a tendency among clinicians to make themselves and their peers a primary object of their therapeutic attention by analyzing themselves and each other.

The pathologization he refers to is a tendency to frame commitment to service as “codependent.”

Though I don’t sense that those particular manifestations of narcissism and pathologization accurately describe the contemporary threats to social work, but I believe narcissism and pathologization are threats nonetheless.

Bill sees a rekindling of service and sacrifice as an essential remedy:

If there is a challenge for our culture and our field in the 1990s, it is the rediscovery of the nobility of service to others. It is the rekindling of the kind of service and sacrifice that springs not from masochism or self-hatred but from the recognition of our connectedness to each other and from the recognition that the self is enriched through acts of service.

While Bill is focused on addiction professionals, this helped illuminate what makes social work special–that we are a profession that explicitly centers the people and communities we serve. We do not center ourselves, our methods, or even other elements of the Code of Ethics. “Social workers’ primary goal is to help people in need and to address social problems. Social workers elevate service to others above self-interest.” The word “primary” communicates this and it’s made more explicit with, “social workers elevate service to others above self-interest.”

This is a feature, not a bug.

Bill was troubled by the changing attitudes toward service among addiction professionals and issued a warning and a call for self-inventory:

Many social commentators have suggested that individuals and countries should choose their enemies carefully because they are destined to become like them. Professional disciplines reflect this same process.

Social workers are underpaid and it’s probably true that we’ve been poor advocates for ourselves. It’s common for people to blame capitalism or neoliberalism for the poor pay and working conditions that are common in the profession. Even defenders of capitalism will often cede that there are sectors where capitalism is not the solution.

If one accepts that the poor pay for social workers is a failure (or feature) of capitalism, it seems strange to attempt to solve that by abandoning or weakening our commitment service as a value. That would appear to be the adoption of the very features of capitalism we reject.

What we need is more effective advocacy, and service can be a central part of that argument. The truth is that it’s hard to serve well if we can’t attract and retain experienced and competent staff because of low wages and poor working conditions.

Effective advocacy requires that we select our targets wisely. The problem is worst in small to medium sized nonprofits. In most cases, these organizations exist in a state of organizational poverty. For workers to target these agencies and their leadership amounts to something akin to lateral violence. In most cases, they are not the problem. The real problem is upstream with funding and reimbursement systems that don’t place appropriate value on the people we serve and the services we provide. Those systems seem to be a more appropriate target for advocacy efforts. Successful advocacy on wages for those smaller agencies without successful advocacy upstream would result in significant erosion of services or closure, leaving government and more corporate agencies as the employers and service providers.

Bill closes with this reflection on the crisis he observed and what he believed was important:

I have tried to define what I consider to be a spiritual crisis spawned by many forces which have worked to divert us from our primary task. Our ability to confront such diversions and get refocused on our primary service mission is crucial for the renewal of the field. In the lexicon of the civil rights movement, we must keep our eyes on the prize. When you strip away all the buildings and budgets, the policies and procedures, and the administrative and supervisory supports, the impact of the whole field comes down to the point of interaction between front line workers and our service consumers-whether they be citizens or clients. It is the transforming power of that point of contact that must be our perpetual focus. That’s where the action’s at. Everything else is secondary.

“Nope. Not today. Maybe tomorrow. Maybe you’ll matter enough tomorrow.”

A friend posted this on Facebook today, regarding something she’s going through—something she’s been going through, and it hit me hard. People commented, poured out love, and told her she matters right now. She matters so much, and I’m sure she knows that, but to someone else in her life—who may hold a key to new beginnings she’s been denied for so long—it doesn’t seem like she matters.

I get that.

My current situation is different, but I’m dealing with my own heartache. I had a huge hand in creating mine, but I still understand how she feels.

For the past two years, I’ve broken my own heart time and again by attempting to make a relationship work that’s just not meant to be. It was my very first “sober relationship,” and I stupidly assumed it would be different (read: healthier) than those I’ve had in the past, because I’m sober.

It was not, and is not. This relationship seems harder, and so do the break-ups (read: multiple).

It’s the same every time we try to make it work, but somehow harder every time it inevitably fails again. We love each other, but we also destroy each other. We can’t seem to leave each other alone, even though we know we should. Even though we have both admitted that our very lives could possibly depend upon it.

IT IS ADDICTION PERSONIFIED. We know this; yet we return.

I’ve been sitting here all morning trying to figure out a way to make this pain go away. All by myself. I know better than that by now. I know I can’t do any of this by myself, but it’s so damn hard to reach out sometimes. It’s almost too exhausting to consider…until I see a post like my friend’s.

She’s hurting, vulnerable, and scared. She’s pissed, and doubting herself. I’m sure she’s experiencing a million conflicting emotions, but she’s not remaining silent, or sitting in secret, agonizing pity. My friend is speaking up, letting us in. She’s letting us know this sucks for her and needs help dealing with it.

No one is going to have magic words or perfect advice to fix this for her. She knows that. But she also knows how powerful sharing her pain can be, and that vocalizing it is the only way she will get relief—some freedom from her mind and weary heart.

My friend has no idea what she’s done for me by expressing this out loud. She will when she reads this.

Thank you for speaking up, and reminding me why I need to. I don’t have magic words for you. Just thank you. For giving me the insight and push I needed to be as brave as you are, and to do what I need to do for me.

Writing this is my first step.

Next, I pick up the phone. I talk to people who love me and understand. I stop hiding and hurting alone, and I take my vulnerable ass to the one place I know I’ll be ok, and spill my messy guts.

I don’t need anyone else to clean up my mess or put me back together again. I just need to allow people to love me where I’m at, help prevent me from going backwards, and stand by me as I get myself to where I need to be.

Lastly, to my friend:

You matter. You make a difference. You save lives. And I really, really hope that they take advantage of the chance you are offering them to have someone as amazing as you in their lives.

This post was submitted by Reagan Post.

Forward: Few people have had as much impact on the way we think about recovery advocacy in America as has Tom Hill. He has been generous of his time with so very many of us in our efforts to strengthen recovery community organizations across the nation. Tom mentored me in his prior role as Senior Associate at Altarum Institute and his efforts to support RCSP grant holders. He helped PRO-A, our statewide RCO here in Pennsylvania to adopt our current organizational framework. Tom has also used his role in the policy realm to develop recovery-oriented systems of care and support efforts to get more people into long term recovery. He is humble and hardworking. Tom is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Johnson Institute America Honors Recovery Award, the NALGAP Advocacy Award and a Robert Wood Johnson Fellowship in the Developing Leadership in Reducing Substance Abuse initiative.

At one point in the interview, he choked up and became emotional, his voice cracking over the phone. It was when he was reflecting on what we have achieved over the last two decades. He was speaking about being able to be open about recovery. He emphasized that just a few years ago, the common public response to a person being open about recovery was revulsion. People like Tom were instrumental in starting us down the path we are on so that we can one day fully normalize recovery and be seen as the key, collaborative stakeholders in matters that impact us.

- Who are you and what brought you to St Paul at that time?

My name is Tom Hill, and I am a person in long term recovery. I came of age in the early days of the HIV movement as a member of the LGBTQ community which a decade earlier organized against stigma and discrimination within our community. We were dying and we needed to stand up or perish. My orientation within the gay rights movement included a framework of social activism and analysis of oppression that informed me as I moved into recovery. Also, as background, I received my MSW in community organizing from Hunter College at City University of New York. Through these experiences and my training, I see myself as a recovery advocate and sometimes a recovery activist. My work in the recovery space was not a planned path, it happened organically.

Prior to my current position, I was Vice President of Practice Improvement for the National Council and a Presidential Appointee in the position of Senior Advisor on Addiction and Recovery to the SAMHSA Administrator and at one point served as Acting Director of the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. I did not strive for a career in government, but at some point, I realized I had a skill set that would be useful in this area of service and so I became involved in Government. As an aside, we need more young people in recovery to consider getting involved in this way, it is an important role.

- Is there a particular moment or memory that stands out to you from that summit?

There were a few moments that stand out. There were two concurrent half day workshops. The first was on organizing and that was facilitated by RAP from Portland, Oregon. Recovery Action Project. The second was a review and analysis of a recovery survey that had been conducted by Peter Hart Associates. It was the Peter Hart session that Gloria Cabrera a member of our group, SpeakOut: LGBT Voices for Recovery spoke up about family as seen through a LGBT lens: about family of origin issues and what was considered safe or unsafe family space.

Another thing that stuck out to me is that the summit was pretty much comprised of older white men. I remember when Gloria stood up and started talking about how the definition of family used in her community was different than how a lot of others in the room defined theirs. I looked around and I realized that most of the people in the room had no idea what she was talking about. In that moment, I was able to see that there was a lot of work that would need to occur to bring diverse perspectives to the table. It is one area I think we could have done a better job. I think we still have a lot of progress to make in respect to diversity.

- What did you see as the motivating factors that brought you all together for that historic summit twenty years ago?

There was a pretty strong desire to develop a national recovery movement and to ensure we are at the table and have a voice in matters that impact us. The kernels of this were in part sewn with work that came out of the original RCSP grants. The statewide network grants came along later (they were dropped into the pre-existing RCSP slots). We are talking about the Recovery Community Support Program, a precursor to the Recovery Community Services Program (same acronym). I was part of one of those first grants as I started Speak Out: LGBT Voices for Recovery. We all came together during that era and started to talk about develop something on the national level. We ended up making some connections with leaders in Minnesota like Jeff Blodgett from the Alliance Project and William Cope Meyers from Hazeldon and the momentum built. It was initially thought by almost everyone that the effort would focus on improving treatment access and strengthening care, but it soon became clear that the communities we were organizing wanted to focus on recovery issues, so this became our focus.

- How have we done in accomplishing those early goals?

We have done so very much over the last 20 years! We developed Recovery Oriented Systems of Care (ROSC) – it came from the recovery community, and we must be involved moving forward for it to evolve in meaningful ways. We have begun to build the community infrastructure that can help encapsulate the recovery experience and support people as they heal. None of those things existed for those of us who needed community support who were coming out of jails, prisons, and treatment centers prior to our efforts. These systems were not even aware of these needs. Our work has led to their consciousness about the need for recovery community support. The very idea of recovery capital and its relation to social determinants of health are things that came out of our efforts, as has the increased focus on trauma, at least to some degree.

There is also lot we have not addressed; we were both in Texas in 2013 when Bill White shared his concerns in his State of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement address. He cautioned us at that time that we should not develop recovery support services along the lines that treatment has been developed. If we allow that to happen we risk failure. I had a sinking feeling at that time that it was probably already happening – the truth is that it did happen, and we need to think differently about how we develop recovery capital in communities. You know this well from your perspective as a statewide RCO leader. We need to address reimbursement and sustainability in ways that reflect our needs rather than rebuild the old system that was not designed to meet those needs.

One of the things we really need to watch out for is the tendency to for government to overregulate, especially states. This is an ever-present risk and there seems to be a particular emphasis on such oversight for those of us in recovery. This may well be reflective of implicit bias within our institutions. The recovery community must remain in control of training and certifying processes like CAPRSS, so we don’t end up going backwards. We need to claim ownership of the recovery supports that we have built and be vigilant that they are reflective of the values and principles that have bubbled up in grassroots recovery communities. We still have not reached a point where people in recovery our seen as capable and equal partners. It reflects the stigmatizing moral lens of addiction: that we are not as trustworthy and need to be watched more closely than people who do not have SUD histories.

- What do you see our greatest successes to date are?

We have profoundly changed how people see SUD care. There was nothing beyond the acute care approach and infrastructure before we started our work. It was always needed and now people wonder why we have not always thought about recovery supports. A decade ago most treatment providers had not even thought about these services or thought of them as “aftercare” which, in most cases, barely existed.

I want to add to this, it is important: We made it okay for people to come out and live openly in recovery. Before this time, people were afraid or too ashamed to come out. When people did share their recovery status, we were looked at with horror. It was a powerful step towards normalizing recovery – to make it so people do not have to be afraid to be who they are or to seek help. It is now easier to live openly in recovery and not be afraid or ashamed or feel like there is something wrong with you. What people looking back need to realize is the very sharing of recovery in public ways was revolutionary, just a handful of years ago. It brings me hope. Our stories have power – we must stay vigilant that our stories are not exploited, sanitized, or cherry-picked in efforts to make us palatable to the larger society and then our stories no longer reflect our authentic and diverse recovery experiences.

- What did we miss if anything looking back at those goals?

I think we have missed self-vigilance in staying on a narrow course – many of us have developed service provider mentalities and become grant focused on ways that are taking us away from the kinds of work we envisioned was needed. We risk losing our way. We also do not have a very politically oriented movement. There is no broad plank in which all of us support and provides a solid political agenda to deliver recovery-oriented care to the next generation. One way for this to happen would be to have all the national recovery organizations come together and agree on things beyond their own focus areas and agree to work on together. There would need to be a focus on developing common goals and develop a political agenda that is widely supported in a nonpartisan way without the infighting that always end up harming all of us.

- What are you most concerned about in respect to the future?

I would refer back to my answer in question six. We have to remain grounded in recovery principles like honesty, integrity and common purpose. If we lose sight of our recovery principles, the work will not be possible.

- What would you say to future generations of recovery advocates about what we did and what to be cautious of / your wishes for them moving forward?

I would tell newer people to the recovery advocacy space to spend some time learning your own recovery history and history of the recovery movement. People must know where they came from and the struggles that have come before their time. There is a long hard road that got us to where we are today. Someone fought extremely hard for the seat you are sitting in. Acknowledging that can be a humbling experience and understanding that you are standing on the shoulders of many of came before you. One final thing is that advocacy does not have to be a career choice and that it is never a substitute for your recovery program, whatever that is. Don’t neglect your self-alignment work, keep your ego at bay, and stay focused on pushing our accomplishments further ahead.