Across our nation, far too often patients are treated rudely or provided inferior care when their healthcare provider learns that they use drugs, have a history of using drugs or are in recovery. Stigma is often the primary barrier for people seeking help. To shift these negative perceptions and improve care within our healthcare systems, we first must develop insight into the scope of the problem. Then we must commit to changing it.

In April 2022, Elveyst and PRO-A released a report highlighting a large-scale survey of Americans’ opinions regarding perceived social stigma against People Who Use Drugs or are In Recovery (PWUD/IR). How Bad Is It, Really? Stigma Against Drug Use and Recovery in the United States examined differences in perceived societal stigma across a vast range of demographic factors, including age, race, and socioeconomic status. The key learning from that research endeavor was that, despite major efforts by governmental bodies and the nonprofit sector to combat stigma against PWUD/IR, perceived societal stigma remains highly prevalent. Consequently, it is a significant obstacle to improving the policies and practices that can reduce stigma, save lives, and help people thrive in recovery.

We just released a new report earlier this week, Opportunities for Change, An analysis of drug use and recovery stigma in the U.S. healthcare system. It is the largest research survey to date assessing endorsed and perceived substance use and recovery stigma expressed by U.S. healthcare workers, as compared to non-healthcare workers. The report includes key findings from health care workers from across the country, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, paramedics, and healthcare systems support staff.

We decided to examine stigma in medical care settings because improving care for PWUD/IR cannot effectively occur unless we understand the breath and scope of negative perceptions that exist in our healing institutions. The attitudes, perceptions, and biases that healthcare workers have in respect to drug use negatively impact patient care. This is a topic I have explored here many times, including in the May 2022 post on Algorithms of Medical Care Discrimination.

The totality of negativity surrounding drug use and recovery in the healthcare setting is vast, impacting views within the professional practice of many healthcare workers who care for PWUD/IR. It results in fewer people seeking help.

It is a case of “physician heal thyself” as the attitudes are killing those who hold them. 40% of healthcare professionals we surveyed use drugs, have an SUD, or are in recovery. The Ohio PHP Executive Report Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on the Health and Well-being of Ohio’s Healthcare Workers, notes that substance use increased 25% during the pandemic. There was also a 375% increase in healthcare workers who report feeling hopeless and overwhelmed. Just like the rest of us, many used drugs to cope with the pain that came with the pandemic. When their use becomes problematic, healthcare workers don’t seek help because of the very attitudes held across their own professions.

There is no time to change like the urgency created in a crisis. This crisis provides us an opportunity to change our attitudes about one of our biggest public health crisis. It is our hope that are work here contributes to changing the attitudes about substance misuse and addiction within our healthcare system. Changing these attitudes is paramount to improving SUD and other healthcare for PWUD/IR across our nation. In respect to our newest report, Opportunities for Change, our findings include:

- Healthcare workers are slightly more positive than the public about the possibility that a person can maintain recovery, yet 38%, (nearly four out of ten), believe a person has a low or no chance of maintaining recovery.

- The PWUD/IR cohort reported the most favorability toward harm reduction, followed by the healthcare provider cohort, followed by all participants.

- Healthcare workers who answered that they are “definitely not willing” to have a PWUD/IR neighbor also answered that PWUD/IR receive worse care (28%), rather than the same care (21%) or better care (22 %).

We conducted this groundbreaking survey in order to improve the care of PWUD/IR receive within our healthcare systems. We cannot properly help people who experience issues with their substance use within a system of care with these pervasive attitudes. This is our opportunity for change and millions of Americans are depending on us to improve these attitudes and by extension the care provided to PWUD/IR.

Substance misuse and addiction and the corresponding stigma are complex issues which will require broad systemic changes to resolve. Addressing these issues will require leadership that brings together our healthcare systems and the communities impacted by the pervasive negative perceptions that exist within these systems. There is cause for hope, as we note that there are segments of care within these facets of this survey which suggest more open attitudes about us, but much more needs to be done. We envision processes that support dialogue to improve these perceptions and as a result, improve the healthcare of millions of Americans who use drugs or are in recovery.

Please feel free to circulate this report. Please also share your thoughts on our findings and on ways to improve the attitudes about substance use or to continue this much needed conversation.

Markita Renee is thriving. Now four-plus years in recovery, she runs OOAK Services LLC where she is a recovery coach, motivational speaker, and facilitator. In addition to that, Markita works part-time as an employment specialist for the state of Connecticut’s Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, facilitates two SMART Recovery meetings, and loves being a great mom to her daughter Si’miaya. And how all of this came together still amazes her.

It was just a few years ago that Markita’s life was a swirl of chaos and longing. In 2014 she lost all contact with her son after he was taken by his father, in 2015 she and her daughter became homeless, and during this time she was under court supervision for a felony charge. All these circumstances fueled her opioid use disorder and compounded alcohol misuse going back to her college days. She managed to get a job, but continued to struggle with substances. At one point everything crystallized into a gut-wrenching realization, followed by a single question, “Either I’m going to kill myself from overdose…or am I going to face what is in front of me and fight?”

This brutally honest insight seemed to trigger positive motion. Markita seized an opportunity to relocate from Oklahoma after her legal issues were resolved and joined a family member in Connecticut. She was working but it wasn’t a good situation. Markita took a deep breath and decided to believe in herself enough to leave and look for something better, and that was when she started OOAK Services. Right after that the March 2020 pandemic lockdown happened.

At this critical point Markita’s resolve to face any and all circumstances and fight for a better life was fully in effect. She chose to go back to school and study psychology, “I decided that the pandemic was a blessing in disguise, took that energy, and applied it to my education.” Then, in what she sees as a sort of destiny, she found SMART Recovery.

The class assignment was to research an organization in the recovery field. Markita doesn’t know exactly how it happened, but SMART popped up on her computer and it was an instant, heart-felt connection. SMART’s focus on self-empowerment and practical tools resonated mightily. She liked that it wasn’t about being told what to do—something Markita had always resisted while growing up. She wanted to know more and go beyond that class assignment.

Markita decided to learn everything she could about SMART and that led her to take the meeting facilitator training. It felt natural and right, “With SMART [you have] so many tools, so many resources, but you create your own path, it’s up to you.” That is the primary message she reinforces for participants in her meetings, but there are other aspects of being involved in SMART that are important to her.

Markita agreed to join a SMART committee that is focused on increasing diversity and inclusion for the BIPOC community, and was a panelist at a recent webinar examining diversity issues. For her, it’s a matter of BIPOC individuals being able to see that there is a place in SMART for them, and that people who look like them are part of the organization.

Markita’s next goal is to get a master’s degree and become a therapist. She sees this as her calling, a way to, “Grow and elevate and serve my purpose of why I’m here as a human being.” From SMART’s perspective, Markita is already serving a great purpose by bringing her gifts and positive attitude to those in her meetings and the larger SMART community.

This blog was also published in STAT on February 8, 2023.

Though it may be hard for many to fathom, even pregnant people and new parents can have active substance use disorders. They need support, not criminalization.

The addiction and overdose crisis, which now claims more than 100,000 lives a year, shows little sign of abating, and emerging data highlight its startling impact on pregnant people: Overdose is now a leading cause of death during or shortly after pregnancy.

Columbia University researchers recently reported that drug overdose deaths among pregnant and postpartum people increased by 81% between 2017 and 2020. In September 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released data showing that deaths related to mental health conditions, including substance use disorders (SUDs), account for 23% of deaths during pregnancy or in the year following it. This outstrips excessive bleeding, cardiovascular conditions, or other well-known complications of pregnancy.

These stunning data highlight just how important it is to ensure access to substance use disorder treatment for pregnant and postpartum people, including the need to eliminate barriers that interfere with this treatment.

In the United States, quality addiction treatment is notoriously hard to come by, especially in rural areas and especially for people from some racial and ethnic groups. Even for those with health insurance, addiction treatment is not covered equitably, so getting care may be expensive. And fewer than half of addiction treatment programs prescribe effective medications like buprenorphine for opioid use disorder.

People seeking treatment for addictions face additional obstacles, especially if they have children. Only a small minority of treatment facilities provide child care, creating yet another obstacle on top of securing transportation, housing, food, and other necessities, all of which can be more difficult for people who are also supporting children.

The barriers get even higher for pregnant people. In one recent study using a “secret shopper” approach, callers to addiction treatment providers in 10 states were 17% less likely to receive an appointment if they said they were pregnant. Pregnant Black and Hispanic people experience even greater challenges accessing addiction treatment, including being less likely to receive medication for opioid use disorder, a proven and cost-effective treatment.

Fear of criminal punishment deters many pregnant people from seeking help for drug or alcohol problems. Many U.S. states have punitive policies in place related to substance use in pregnancy, which may include regarding it as potential child abuse, or grounds for commitment or being charged with a criminal act. Penalties for substance use in pregnancy can include fines, loss of custody, involuntary commitment, or incarceration.

Between 2011 and 2017, the number of infants placed in foster care grew by 10,000 each year; at least half of those placements were associated with parental substance use. Children in states with punitive policies are less likely to be reunited with their parents than those in other states. Moreover, there are considerable inequalities within the child welfare system. Pregnant Black people are more likely to be referred to child welfare and less likely to be reunited with their infants than pregnant white people, and Black and American Indian/Alaska Native children are overrepresented in this system.

It’s no surprise that punitive policies cause pregnant people to fear disclosing their substance use to their health care providers or to avoid seeking treatment for a substance use disorder. These policies may also cause them to avoid or delay getting obstetric care.

Decades of research show that addiction is a chronic but treatable condition that drives people to use substances even if it harms their health, careers, and relationships. Punitive policies are not effective at addressing substance use disorder and, if anything, only exacerbate its societal risk factors, including worsening of racial health disparities. Punitive approaches also lead to more negative outcomes for parents and their children.

In states more likely to criminalize pregnant people with opioid use disorder, fewer receive medications for it. A 2022 analysis found that women living in states with punitive policies for substance use in pregnancy had a lower likelihood of receiving timely or quality care, both before and after pregnancy. In states with such policies, or which require doctors to report their patients’ substance use, prenatal care tends to be sought later in pregnancy. States with punitive policies toward pregnant people with substance use disorders have higher rates of infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome.

In addition to increasing a mother’s risk of overdose, untreated opioid use disorder during pregnancy can cause fetal growth restriction, placental abruption (separation of the placenta from the uterus), preterm labor, and other problems, and sometimes even the death of the fetus. Treatment with methadone or buprenorphine reduces the rates of preterm delivery, low birth weight, and placental abruption. Treatment also helps people with substance use disorders stay employed, take care of their children, and engage with their families and communities.

Like other medical conditions, substance use disorders require effective treatment. Science is poised to help as ongoing research develops more safe and effective interventions, as well as better implementation models tailored to the needs of those seeking substance use disorder treatment during pregnancy.

Punitive policies toward substance use reflect the entrenched attitude that addiction is a deviant choice rather than a medical disorder. A shift away from criminalization will require a shift of societal understanding of addiction as a chronic, treatable condition from which people recover, underscoring the urgency to treat and not punish it.

Having a substance use disorder during pregnancy is not itself child abuse or neglect. Pregnant people with substance use disorders should be encouraged to get the care and support they need — and be able to access it — without fear of going to jail or losing their children. Anything short of that is harmful to individuals living with these disorders and to the health of their future babies. It is also detrimental to their families and communities, and contributes to the high rates of deaths from drug overdose in our country.

Nora D. Volkow is a psychiatrist, scientist, and director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which is part of the National Institutes of Health.

Around this time of year, love is in the air and people everywhere are ready to celebrate that love with the ones closest to them. Sounds perfect, right? Well, if you don’t have that special someone to share the holiday with this year, you may not be feeling like celebrating. On the other hand, maybe you do have a loved one you’d like to enjoy Valentine’s Day with, but you’re early in your recovery and worried that not being able to indulge in your past V-Day traditions – champagne, wine, cocktails – will prove to be too triggering or difficult and lead to relapse. Either way, February 14th may not seem like the stress-free day of love that it used to be.

Around this time of year, love is in the air and people everywhere are ready to celebrate that love with the ones closest to them. Sounds perfect, right? Well, if you don’t have that special someone to share the holiday with this year, you may not be feeling like celebrating. On the other hand, maybe you do have a loved one you’d like to enjoy Valentine’s Day with, but you’re early in your recovery and worried that not being able to indulge in your past V-Day traditions – champagne, wine, cocktails – will prove to be too triggering or difficult and lead to relapse. Either way, February 14th may not seem like the stress-free day of love that it used to be.

Here are a few ideas to help you get out of your head and be able to enjoy the holiday of love with your partner, your family, or with your own company – which can be the best company there is!

- Enjoy a mini-vacation weekend. Drive out to the beach, to the mountains – anywhere you (and/or your partner) can go clear your head and leave behind the hustle and bustle of everyday life. Use the holiday as a chance to rest up and spend quality time alone or with your partner around beautiful scenery.

- Write a love letter to your Higher Power. Give yourself a reason to show gratitude for your recovery on Valentine’s Day. List out ways in which finding your Higher Power has improved your life, and ways in which you plan to strengthen your relationship with your Higher Power as you continue navigating your recovery.

- Spend time with family. Valentine’s Day isn’t solely concerned with romantic love. Show the people in your family that you love and appreciate them by giving them a kind gift or going out to a nice meal together. Keep your family bonds strong so that they can continue being there for you in your recovery.

- Attend a meeting. If you’re alone and struggling with your recovery on Valentine’s Day, you’re absolutely not alone. Find a nearby meeting to attend so that you can connect with others and receive encouragement and support to keep going. If you have a partner, perhaps spend time with them looking for local Al-Anon or Nar-Anon meetings that they can start attending.

- Stream a favorite movie or show. If all else fails, Netflix will always be waiting for you. Grab some chocolates or some cake and snuggle in with your favorite film or TV series – nothing heals the heart like comfort and familiarity (and sugar).

However you end up spending your Valentine’s Day, remember: You are not alone. One of the most important recovery messages rings even truer on a holiday centered around love and deep, meaningful social interactions. No matter what your situation is, there are people out there who support you and are ready to show you and your recovery love whenever you are ready to receive it. Enjoy your holiday, and more importantly, enjoy those chocolates!

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The post Keeping Love Alive: Navigating Valentine’s Day in Recovery appeared first on Fellowship Hall.

Aaron Adkins loves everything about being in recovery. He lists the support he gets from his SMART Recovery peers, the practical tools he uses to address negative thinking, the understanding and insight he gains from being a meeting facilitator, and, perhaps most especially, being able to give back as a mentor to other facilitators. “It’s been a wonderful way for me to understand how I do what I do…being able to teach something just kind of takes me to the next level.”

Certainly, the level Aaron exists on today is much higher than when he was struggling with his addictions. There were two arrests for driving under the influence, job losses, financial ruin, visits to the emergency room and multiple mental health crises. It didn’t matter whether he lived in California or moved his troubles to Washington D.C.: what finally helped end the chaos was the discovery of SMART.

Aaron embraced SMART’s principles and practices starting in 2017, and began making better decisions about how he interacted with the world. He overcame his fear of making changes, and now celebrates developing new skills to confront distorted thinking using SMART’s ABC tool and others. He treasured the help he got from his meeting facilitator, and eventually took a suggestion to become a facilitator himself. From there, it was a natural choice to want to share his experience through SMART’s Facilitator Mentoring Program.

“Recovery is not going to be successful for me if I just take my sack of gold and walk away,” says Aaron. Instead, he finds teaching the tools to new facilitators not only helps them find their own strengths but energizes him. He says the essence of being a mentor is, “Being able to partner with someone on their journey, help them find their path, hold up that lantern…” In other words, he says, “Nobody has to go it alone when it comes to being a SMART facilitator.”

Aaron says the time and energy he devotes to mentoring is not a burden; instead, “It’s the gift I didn’t know I wanted.” And it’s safe to say that those whom Aaron mentors and interacts with feel they are receiving a great gift themselves.

For more information about the Facilitator Mentoring Program, visit here

Today is the 10 year anniversary of my organizational workplace making the switch to a tobacco-free campus.

Prior to the change I was involved in organizing and leading our attempts to address tobacco smoking. After we made the switch to a tobacco-free campus, I looked back and realized those earlier efforts were like our organization going through the stages of change.

Making the switch to a tobacco free campus was a total team effort and involved leadership from every part of the organization. It required input and support from every department. Here’s an article we published in 2014 about our change process. It’s a quick and accessible read that covers a lot of ground from rationale, to policy and procedures, obtaining staff buy-in, and more.

Looking back across the ten years, what are some main takeaways or points of learning? A few come to mind.

Sustaining a change is different from making a change.

- About two years after our change we realized new staff did not have a shared understanding with existing staff. We added staff training on the topic as a routine matter. This helped all staff have a shared understanding.

- We encountered some difficulties after the first year related to long-term maintenance of the change. These were simple stuck points but we did not anticipate them. We re-formed the steering committee that led the initial change in order to help identify difficulties and build structures to support the project for the long-haul.

- After a year or two, with the process going well, we figured out we had to help some staff re-solidify their commitment and improve their intentional effort. The success of the effort over time had led to some diminishment of commitment and focus for some staff. This was easily rectified with some intentional effort and support in clinical supervision.

I’ll close with a word of encouragement related to community. During the early years of our process I learned that other organizations were also making this change, or preparing to. And I learned there are people with career-length expertise on this topic working in academia, public health, policy, and diverse community settings. And I came to realize, as is so common in our work, that the vast majority of them are very ready, willing, and able to share what they know, give away what they have, and help others succeed. I learned, at the organizational-leadership level, we don’t have to do this alone and that allowing others to help us is a very good thing.

Related Reading

Our Unconscious Relationship with Tobacco. This challenging article encourages the reader to reflect on the topic from a relatively uncommon perspective.

Appearance and performance enhancing drugs (APEDs) are most often used by males to improve appearance by building muscle mass or to enhance athletic performance. Although they may directly and indirectly have effects on a user’s mood, they do not produce a euphoric high, which makes APEDs distinct from other drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and marijuana. However, users may develop a substance use disorder, defined as continued use despite adverse consequences.

Anabolic-androgenic steroids, the best-studied class of APEDs (and the main subject of this report) can boost a user’s confidence and strength, leading users to overlook the severe, long-lasting, and in some cases, irreversible damage they can cause. They can lead to early heart attacks, strokes, liver tumors, kidney failure, and psychiatric problems. In addition, stopping use can cause depression, often leading to resumption of use.

Because steroids are often injected, users who share needles or use nonsterile injecting techniques are also at risk for contracting dangerous infections such as viral hepatitis and HIV.

Steroids are popularly associated with doping by elite athletes, but since the 1980s, their use by male non-athlete weightlifters has exceeded their use by competitive athletes.1 Their use is closely associated with disordered male body image—most specifically, muscle dysmorphia.

Hands holding binoculars on green background, looking through binoculars, journey, find and search concept.

Protecting your recovery at all costs must be emphasized at all stages of recovery. Relapse starts well before a person picks up using a drink or a drug, so developing insight into your relapse triggers is a concept that needs continual assessment and evaluation during and after treatment. You may ask, “What the heck is a trigger?” A trigger can be best described as a person, place, thing, feeling, or situation that leads to a thought that taking a drink or using a drug would be a good idea.

As a person in recovery, it is your responsibility to identify and be aware of your own triggers. A trigger prompts a thought, which if it is romanced, can become a craving. Smash that thought, play the tape to the end, and remember the pain you felt in active addiction. Remember the H.A.L.T concept. When you become restless, irritable, and discontent, continually ask yourself, “Am I hungry, angry, lonely, or tired?” If so, these feelings could increase the risk of relapse. Only you have the power to address these feelings with the recovery tools you now possess.

We encourage people new to recovery to focus on developing healthy communication skills and learning to be emotionally intimate with peers before diving head first into a relationship rooted in physical attraction. In early recovery, the newcomer is still early in developing healthy emotional coping skills. Romantic relationships and sexual acting out can detract a person from focusing on sobriety and often leads to a quick relapse. Most addicts and alcoholics have used alcohol or drugs to cope with emotions. The newcomer is an infant in emotional sobriety. Talk about feelings openly in meetings and with a sponsor. Most people will never heal what they do not feel.

Living in recovery will give you a life worth living. Be aware of complacency, euphoric recall (thinking back to your drinking or using with happiness or nostalgia), and forgetting the pain that addiction has caused. Be conscious not to drift away from recovery. Regular AA and NA attendance is extremely important. It’s an easy and common mistake for people to reduce meeting attendance, stop calling a sponsor, or just stop going to AA/NA altogether! Again, recovery gives people a great life that can end up taking them right back out of recovery when life improves. Remember, the brain chemistry has been changed. You will be triggered at some point in time. Tell on your disease before a trigger is romanced into a craving. Remember to continually assess your motives for being around certain people or going certain places. Think before you drink or use. The time to call your sponsor is before, not after! One Day at a Time.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The post Staying on the Lookout for Relapse Triggers appeared first on Fellowship Hall.

Ok… let’s talk.

A company called Ophelia Health has launched a new marketing campaign focusing on the message “F*CK REHAB”.

On the one hand, there’s A LOT to criticize in the addiction treatment world. At the provider level, there is a long history of really bad, predatory, poor quality, and abusive treatment springing from ineffective models, stigma, profiteering and exploitation. At the system level, we’ve never had real parity with care for other diseases, adequate funding, and cohesive systems of care.

Examples include tonic cures, cults (see also here), patient brokering, lobotomies, exorbitant lab fees, abusive teen programs, and cash-only office-based treatment. Some examples include treatment models or delivery methods that are inherently flawed and unethical, or ineffective under any circumstances. Other examples involve issues with quality, intensity, duration, or the integrity of the provider.

Bill White described 1980s treatment providers losing their way as they shifted from mission-oriented organizations to profit-oriented.

In the 1980s, addiction treatment programs shifted their identities from those of service agencies to those of businesses. A growing number of for-profit companies that measured success in terms of profits and quarterly dividends–rather than treatment outcomes–entered the field….

…Their self-images shifted from those of public servants to those of health-care entrepreneurs. For a time, a predatory mentality became so pervasive that it affected even some of the most service-oriented institutions. In this climate, alcoholics and addicts became less people in need of treatment more a crop to be harvested for their financial value. This evolving shift in in the character of the field left in its wake innumerable excesses that tarnished the public image of the field and set in motion a financial backlash that would lead to fundamental changes in the primary treatment modalities available to addicts and their families.

William White in Slaying the Dragon

I assume that Ophelia’s use of “rehab” refers to inpatient and residential programs, which dominated the industry in the 1980s. Over the last couple of decades, many residential programs have been among the worst offenders, with exorbitant rates, misleading marketing, inadequate duration of care, poor quality monitoring, and, in some cases, fraud. That there have been serious problems in residential programs does not mean that residential programs are universally problematic.

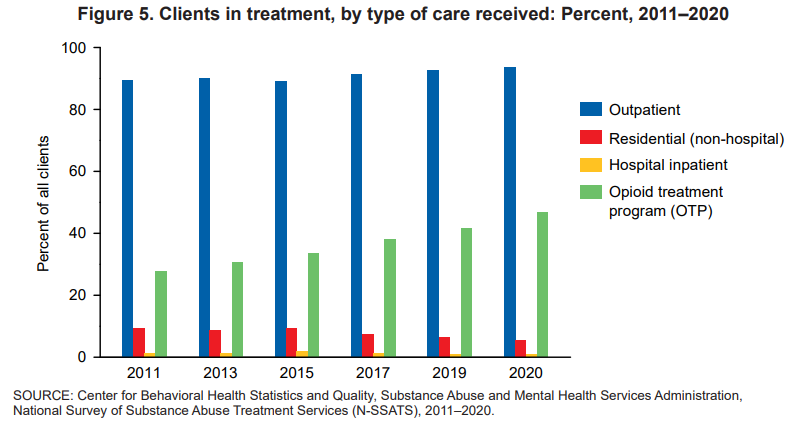

It’s important to note that residential and inpatient make up a relatively small and shrinking fraction of the treatment provided in the US today. (Note that this graph represents ALL clients, not just clients with opioid use disorders.)

Between 2011 and 2020, the proportions of clients in treatment for the major types of care—outpatient, residential (non-hospital), and hospital inpatient— shifted. Clients in outpatient treatment increased from 90 to 94 percent while clients in residential (non-hospital) treatment declined from 9 to 5 percent. The proportion of clients in inpatient hospital treatment ranged between 1 percent and 2 percent from 2011 to 2020

National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2020

I spent 25 years as part of a program that included outreach, outpatient, peer support, detox, residential, housing, and linkage to primary care that would help monitor recovery. We also took informed consent very seriously, with repeated discussions about the treatments we offered and didn’t offer and active linkage to treatments we didn’t provide. More recently, I spent 3 years as part of an inpatient unit that inducted a lot of high severity and high chronicity patients on agonist treatments. Programs like those — that provide rigorous informed consent and a continuum of long term care, or routinely initiate agonists — may represent a minority of inpatient and residential providers, but they were not alone.

Is “rehab” bad and telehealth good?

Ironically, digital behavioral health providers (Ophelia’s business category) have gotten some attention lately.

First, the Wall Street Journal reported on quality problems and prioritizing profits and the next round of venture capital over ethics and standards.

“When you put venture capital money into this mixture, it really pushes people to take risks,” Ms. Moore said. “It’s one thing to be a disruptive innovator, but there’s a reason medicine is encumbered by so many regulations — we’re dealing with people’s lives.”

Winkler, R. (2022, December 19). The failed promise of online mental-health treatment. via TheAustralian.com.au; The Oz.

A few months ago, a JAMA study was published and lauded as evidence for the effectiveness of MOUD (medication for opioid use disorder) treatment delivered via telehealth.

In a post about that study, I framed its findings as follows:

I want to make it clear that I harbor no skepticism about the importance of telehealth services as part of an effective system of care. With the explosion of telehealth during the pandemic, I’ve seen the benefits of telehealth in the engagement and retention of patients who might never try in-person services or stay engaged with in-person services for reasons as varied as transportation, scheduling, temperament, and medical or psychiatric comorbidities.

The study looked at medication retention and medically treated overdoses before and during the pandemic, with the before-pandemic group representing office-based care and the during-pandemic group representing telehealth care. They found good news and bad news.

The good news was that shifting to telehealth did not adversely impact either of these outcomes.

The bad news was that I found the outcomes to be very disappointing.

Retention rates for buprenorphine (defined as use over 80% of days) over 6 months were 31% for the office-based group and 33% for the telehealth group.

Retention rates for extended-release naltrexone (defined as use over 80% of days) over 6 months were 8% for the office-based group and 12% for the telehealth group.

18% of each group experienced a medically treated overdose during the study period.

The subjects were all Medicare patients. They had to meet age or disability requirements to enroll. However, the retention rate is not inconsistent with what I’ve seen in other studies with other populations.

I imagine most patients and families are looking for treatments that offer better than a 1 in 5 chance of an overdose, and 2 in 3 chance (or 9 in 10 for extended-release naltrexone) of discontinuing treatment within 6 months.

Are those outcomes explained to patients? Are they offered other options?

This criticism isn’t about the treatment being offered (in this case, medication) or the method of delivery (telehealth or in-person). My criticism is about the system of care that doesn’t offer treatment and recovery support of adequate duration, intensity, quality, and scope. (This is the norm whether you’re entering residential, outpatient, or office-based MOUD.) Further, it’s representative of an evidence-base that tends to speak only to outcomes like medication retention and overdose.

Treatment as usual isn’t cutting it (same for research as usual)

Ophelia’s “F*CK REHAB” evidence

Ophelia offers limited evidence for their marketing campaign. The screen capture above provides 2 bullets that speak directly to “rehab.”

- The first states that 2/3 of “rehabs” don’t prescribe medication.

- The second reports that “Once released from rehab, 90% of people who do not receive medication relapse within 3 months.”

Both points cite the same source: Bailey, G. L., Herman, D. S., & Stein, M. D. (2013). Perceived relapse risk and desire for medication assisted treatment among persons seeking inpatient opiate detoxification. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 45(3), 302–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.04.002

So, what does this article actually say?

The article is a strange choice to support this marketing message and their characterization of it is equally strange.

- It’s 10 years old, based on 12 year old surveys.

- I don’t see where it reports anything about the number of rehabs that prescribe or don’t prescribe medications.

- I don’t see where it reports 90% relapse rates within 3 months for people who don’t receive medication, but it does say that 90% of subjects reported relapsing within 12 months of their last detox episode. It doesn’t say whether they received medication in that previous detox experience.

- However, these subjects were current detox patients, therefore 100% of them have relapsed since their last detox episode.

- This study was done with patients currently in a detox program (average stay of 5.9 days) to evaluate their desire for MAT and to investigate the factors that influence this desire.

- This detox program provided methadone tapers, educated patients about MAT, and offered MAT to all patients. They asked about previous detox experiences to evaluate the influence of previous detox experiences on their perception of relapse risk and how that perceived risk influences their preferences for or against MAT.

- Even after a discussion of their relapse history and education about MAT, 37% of patients did not want medication.

- This was not a medication-naive group, many of them had previously received MAT: 43% methadone maintenance, 42% prescribed buprenorphine, and 6% Vivitrol.

So… the article doesn’t say what Ophelia said it said and it really doesn’t even seem to speak directly to their argument.

Ok. So, what about “rehab”?

They never really define rehab, but the study they direct us to focused on a 6 day detox program that tried to connect patients to ongoing care, including medications. (It’s worth noting that this was in 2011 and use of MAT has only increased in the years since.)

I think it’s fair to criticize many residential and inpatient programs, and the opioid crisis has increased the stakes for inadequate and shoddy treatment. I’d agree that detox that is not tied to long term care is unethical. I’d say the same thing about a 30 day destination programs that don’t include assertive long-term care.

However, the model with the best outcomes often includes residential treatment as part of the episode.

Further, our colleague David McCartney reviewed a recent Scottish report on residential rehab that found:

Rehab is linked to improvements in mental health, offending, social engagement, employment, reduction in substance use and abstinence. There is little research that compares rehab with other treatments delivered in the community, but where there is, the evidence suggests that “residential treatment produces more positive outcomes in relation to substance use than other treatment modalities.” The review also suggests that rehab can be more cost-effective over time than other treatments.

Where does this leave us?

The study Ophelia directs us to found a significant minority of patients do not want medication, despite considerable experience with medication among the subjects.

The JAMA evaluation of telehealth MOUD treatment found 67% dropped out by month 6, and 18% overdosed.

A Wall Street Journal investigation demonstrated that deficiencies in quality and ethics are a significant problem in digital behavioral health. (As has been the case in other treatment approaches.)

Years ago, having reached the conclusion that there is no silver bullet in addiction treatment, I came to believe that the only responsible systemic approach is to:

- offer a complete array of services;

- of adequate quality, intensity, and duration;

- by people who believe patients can achieve full sustained recovery (or flourishing);

- provide accurate information on their options (and the options not offered);

- let them choose the treatment approach that best fits their preferences and goals; and

- allow them to change their mind as they experience successes and setbacks, and their preferences and goals change.

I’ll leave you with a couple of thoughts from colleague David McCartney.

First, some of his thoughts on polarization in the field of addiction treatment and recovery support:

When those new to the addiction field question how unhealthy it seems, we all ought to sit up and take notice. We are responsible for the culture we have created. If that is a culture of conflict, we need to attend to it. Leaders have a particular responsibility here – we ought to be held to a high standard of behaviour and professionalism. That need not make us impotent, but rather be mindful of the power that we hold and how we use it. Change starts with ourselves.

There’s one more thing – another value – that is missing when there is turmoil. That value is humility. It’s not reasonable to expect that we all agree on everything all the time. This would be a disaster – we need to feel discomfort, disagreement and passion; these can be potent drivers for positive change, but perhaps a little bit of ‘I could be wrong and others right’ would go a long way to pour oil on troubled waters.

Polarisation, tension and hostility: just another day in the field of addictions.

Finally, from his post examining the effectiveness of residential rehab:

We don’t need to say one thing is better than another, but we do need choice and through shared decision making we can try to help patients align themselves to a treatment option that helps them meet their goals. And we need to be humble too. Evidence suggests that over a lifetime, most people resolve their problematic use of substances. When they look back, they may be grateful for the part that treatment played in their recovery, but it is likely that it will be only one of many factors that helped.

For the moment though, we can certainly challenge the voices that say ‘there’s no evidence that rehab works’, for there is ample evidence that it does. I’m not unrealistic about this though. As I’ve been writing, I have been mulling over the wisdom of Ahmed Kathrada’s observation: ‘the hardest thing to open is a closed mind’. That shouldn’t stop us trying.

Over the course of my decades of work in the SUD field and as a person in recovery, I can honestly say that I have tried as hard as I can to do my very best to serve people in need of help with a substance use condition. I suspect most others in this field share this same ethic. I would also tell you that despite this level of dedication, over the years I have occasionally found that I harbored deep-seated, hard to spot, negative views about people with addictions. They came out in ways that I was not always able to recognize at the time. I suspect I am not alone in this either.

Recently, I worked with a group of researchers in a focus group examining barriers and strains on addiction treatment at the national level. There were other people from across the United States on the call with truly horrific experiences in our service system. An unfortunate yet far too common experience. For readers, please know that there are a lot of caring people who do their best with all the limitations faced to serve people. However, it is also true that one does not have to dig very far to hear horror stories of poor care and punitive treatment posing as help. As the discussion ensued, we agreed that if we ended up getting rid of our entire SUD workforce and care system and rebuilding it, we would likely end up in the very same place. The changes we need to make are more foundational.

There are bodies of research on how even people in recovery look down on ourselves and each other as a result of the all-encompassing stigma in our society. These hidden attitudes are known as implicit biases, and they are everywhere. We really do not know what we don’t know, and they influence everything we do. We must do a better job of identifying it and addressing them to move forward. Anything less simply will not work.

Over the course of my decades of work, I have consistently found that the root cause of most of our challenges is the deep negative perceptions in America about addiction and recovery. The widely held and far too often verbalized belief that we are “those people who did this to themselves” and that people like me ultimately do not deserve help. It is why we provide care at shorter durations and lower intensity than needed and fail to invest in authentic recovery supports in our communities. As a result, fewer people than should find recovery. This is a negative feedback loop that validates to a relatively hostile society that we do not actually get better, leading to even more suboptimal care.

The unblemished truth is that many people in our society openly look down on us. As I have noted in past writings, my organization, PRO-A did a large survey on perceived stigma nationally with RIWI and Elevyst. Our report, HOW BAD IS IT, REALLY? Stigma Against Drug Use and Recovery in the United States examined perceived stigma and found that 71% of Americans believed that society sees people who use drugs problematically to be outcasts or non-community members.

Three out of four respondents perceived that society sees us as outcasts. I see it with my own eyes. I have heard people around me say horrific things about people like me. Consider “take the drug addicts out to the hospital parking lot and shoot them.” People die every day from these attitudes. We found somewhat lower rates of endorsed stigma on a more recent study of medical stigma in the US, but much higher than we would like to find. These attitudes are everywhere.

They can be very subtle or in your face. It was what Kristen Johnston spoke about when reading the epilogue of GUTS ten years ago when a friend told her to stay silent about her recovery because it made people uncomfortable. It can look like punishing a person for not responding to the limited services offered. Medical staff who call someone who has experienced multiple overdose reversals a “frequent flyer” and families told to practice “tough love.”

To see implicit bias in action we need to look no farther than a service system that offers less care than the evidence has shown time and time again people need to get better. As Nick Hayes notes in his recent STAT News piece, For addiction treatment, longer is better. But insurance companies usually cut it short. These same systems hammer providers to offer evidence-based care and then, despite the evidence fund services in such a limited fashion that they can’t help. This results in poorer outcomes, which validates the belief that people like me do not heal, resulting in more of the same.

While it is clearly our biggest barrier, the pathway forward is murky. As psychologist Anthony Greenwald explains in making people aware of their implicit biases doesn’t usually change minds. We really don’t have much in the way of evidence-based practice to effectively address implicit bias. He suggests that leaders of organizations need to care enough to track their data to identify where disparities are occurring. Then they need to make changes and examine the next cycle of data to see if things improve. Practices that take commitment and long-term effort.

It is vital that all of us, and all of our institutions, particularly those dedicated to helping us examine how their internal negative perceptions about people who struggle with substances influence policy and practice. Subtle or not so subtle beliefs rooted in moralism, racism and a host of other “isms.” We make it hard for people to get well because of these deeply seated and pervasive negative attitudes. We are often not even aware of these subtle beliefs influences everything we do. These are the foundations are whole SUD care system is built on and it is why over time we tend to set up the same punitive processes over and over across history.

This article, Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. found that healthcare professionals exhibit the same levels of implicit bias as the wider population. We are increasingly focusing resources on integrating SUD services into institutions that harbor deeply held negative views about us. It is clear it will fail unless we reduce the underlying biases and change the culture.

Work is being done within the National Institute of Health to explore effective efforts to address implicit bias. We have a long way to go as noted in this 2021 NIH document, Scientific Workforce Diversity Seminar Series (SWDSS) Seminar Proceedings – Is Implicit Bias Training Effective? It suggest comprehensive approaches must be used and that compulsory single episode trainings are largely ineffective. This may seem prohibitive until we consider that it is virtually certain that if we do not do so, nothing will change.

We must commit to over the long-term to getting rid of the negative perceptions that exist nearly everywhere about addiction and recovery. An example of a place to focus such efforts is the work towards developing recovery-oriented systems of care. Legitimate work in this arena would dedicate resources to finding and addressing implicit bias against persons who experience substance misuse and those of us in recovery at all levels. This would include how such programs are designed and implemented or they will invariably become tools of oppression, because that is how powerful these forces play out across every corner and crevice of our society.

As Wellbriety elder Don Coyhis noted, “all organizations are perfectly designed to get the results they get.” if we want different results, we must redesign the system. This is profoundly challenging. Even systems that do not work offer benefits to those vested in keeping it just the way it is.

To build a system of care that gets more people into wellness, we must dig down deeper and put our institutions on foundations firmly anchored on the bedrock of positive regard. To build a system with recovery at the center. To set up checks and balances to ameliorate the profound impact of these negative views within us all. Not a new concept, just one we have never implemented perhaps because it seems hard thing to do. Instead, we keep trying to build programming on the shifting sands of implicit bias that then erode our capacity to heal.

Processes that perpetuate the system we have:

- Ignoring disparate and discriminatory processes within our systems.

- Lack of transparency in system design, implementation, awarded funding and evaluation.

- Only including impacted recovery communities as proforma participants or not at all.

- Developing programming that ignores feedback from negatively impacted groups.

To move things forward we would need to have:

- System leaders who openly look for blind spots and seek feedback on remediation.

- Disparities in system design and implementation openly acknowledged.

- Systems that develop and fund services transparently.

- Processes in place to identify and address biases within every institution.

- Impacted groups invited and engaged in resolving disparate policies.

- Open cultures dedicated to reducing negative perceptions about persons who misuse substances.

- Diverse communities engaged at all stages of care system development, deployment, facilitation, and evaluation.

Millions of Americans have found recovery. Recovery has profoundly improved our lives and helped us to be better family and community members. All of this has occurred within a system of care that is built on a foundation of stigma. It speaks to the power of recovery that people heal, often despite the system of care rather than because of it.

Imagine what we could accomplish if we addressed the underlying biases in our society that make it hard for people to heal. They are present everywhere, but it is most likely that if we started to address them in our systems of care, we can start to effect change and build a better care system.

The stakes are high. The hard to argue truth is that unless we do so we will keep rebuilding flawed care systems. It may be hard, but not nearly as hard on our society as not doing so.