RISE21 Registration and Housing Open

The world’s preeminent conference on addiction, mental health, and justice reform will be held August 15-18, 2021 just outside Washington, D.C. at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Maryland.

Learn how to register for the conference and secure your housing here

The post RISE21 Registration and Housing Open appeared first on NADCP.org.

In a compelling study from Dublin, Paula Maycock and Shane Butler (Trinity College) make the point that little is known about the stigma experienced by individuals attending drug treatment services over prolonged periods. They explored this through the lived-experience narratives of 25 people prescribed long-term methadone. Their findings ‘reveal the intersection of stigma with age as profoundly shaping methadone patients’ perspectives on their lives’.

I like qualitative research because it is often affecting – stories bring to vibrant life important things we need to consider. You remember stories. You remember the feelings they engender. I connect with qualitative research in a way I never can with tables, graphs and statistics. I connected emotionally with this study.

In this study, 16 men and 9 women were interviewed. Two thirds were over the age of 40 and 16 of them had been on methadone for 20 years or more. Two were now long-term abstinent from all drugs including methadone. Nine people were attending a clinic for daily supervised consumption. Only three of the 20 were employed full-time.

The findings of this paper did not make for an easy read. You can sense something beyond detached academic curiosity here. Butler and Maycock reflect:

An intensity permeated these narratives in the sense that interviewees frequently – and, at times, emotionally – recounted treatment-specific experiences that engendered a sense of ‘otherness’ and shame.

Maycock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 2021

Methadone was seen as an instrument of punishment, ‘reflecting and amplifying’ public stereotypes around drug use and addiction:

It’s so demoralizing to go into the clinic and you’re just, you’re pissing [urinating] in bottles and grovelling to your doctor and grovelling to the chemists and that was your life, that was my life, you know.”

Rachel, service user

The research participants describe feeling ‘not normal’, having to ‘duck and dive’ and being treated ‘like dirt’. The absence of connection with the professionals they had contact with seems astonishing to me and the perception of being controlled or punished by the ‘techniques’ of treatment – e.g. threats of removal of takeaway doses for ‘dirty urines’ – was upsetting. Bad experiences reportedly extended to pharmacies where ‘public shaming’ took place.

The relationship with age and time on MMT (methadone maintenance treatment) was explored – there was a particular shame around being on methadone at an older age or for a longer period of time, such that individuals wanted to hide this, in a way that did not apply to other prescribed medications for other conditions.

The most harrowing theme in the paper is what Mayock and Butler call the private burden of stigma – the pernicious inner voices suffered by the participants, instilled powerfully and cemented down by years of reinforcement. The result is diminished spirit, low self-esteem and an erosion of humanity .

That’s what you do as a drug addict – you let people down, you’re unreliable, you’re of fucking no use to nobody.

Cormac, service user

The authors’ conclusion is hard hitting:

The lived experience of long- term MMT in Ireland is one characterized by relentless stigmatization, reflecting the marginal position of addiction treatment within the wider healthcare system and a failure to normalize methadone treatment.

Maycock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2021

It’s impossible not to have a strong reaction to this paper – it made me angry and sad and frustrated, but we do need to be a little careful here. The numbers are small, this is only one area of Ireland, and we are not hearing the other side of the story – how providers might see the situation and what limitations and duress they are working under, but that said, this is powerful stuff which merits consideration and further research.

So, what’s to be done?

The authors identify some issues specific to Ireland relating to the introduction of MMT which may be partly responsible, and they welcomed a policy shift away from criminal justice approaches towards a health approach, accepting that the tensions between the two are difficult to erase. They question the impact of a public campaign to tackle stigma, instead calling for organisational change in clinics and social structural change outside of treatment settings. Perhaps the most profound challenge they give us though is what we do with the upsetting legacy of what we’ve read in this paper.

I come back to a concern that bothers me here: the tension between what’s good for public health and what individuals want from treatment. The subjects in this research can’t have entered into treatment because they were seeking public health benefits from MMT – they would have wanted to see their lives getting better. The authors acknowledge this explicitly:

The well-documented public health benefits of MMT were not matched by a perceived improved quality of life among this study’s methadone patients

Maycock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2021

Maycock and Butler have looked at this in more depth in a separate paper (which I’m planning to come back to a different time) where people (the same ones I suspect) on MMT report being ‘passive recipients of a clinical regime that offered no opportunity to exercise agency’. This observation fits in with studies from elsewhere prompting the development of a large scale study looking into quality of life of those patients in treatment on MAT recently announced in the British Medical Journal.

While methadone and other examples of MAT have strongly evidenced benefits, medication does not offer meaningful healing for hurts. Methadone is not the problem here, nor is this only about stigmatisation. If we give methadone the blame we miss a trick.

I was struck by the absence of any meaningful interventions reported in the clinical settings where methadone was dispensed. Where was the compassionate approach to trauma? Where were the practical supports for housing, benefits, employment, families? Where was the mental and physical health support? Perhaps it was there but not reported, which says something in itself.

What would it have been like, I wonder, if the individuals had been offered meaningful support and interaction in each setting – primary care, clinic, pharmacy – by peers with lived experience? There is a call by the authors for involvement of stakeholder groups committed to harm reduction, but why not committed to harm reduction and recovery? Harm reduction is essential, but it’s not an end in itself. I have written recently about this quoting Eric Strain who talks about the importance of finding meaning and purpose and allowing people to ‘flourish’ in treatment.

So why not have peers on MAT, for instance, who had achieved their goals from treatment. Or peers who had moved on from MAT to abstinence? Or a mixture. What if clinics were perfused with hope and that hope was embodied in peer role models who had knowledge and experience of moving on and developing – of flourishing?

I have another concern. The word ‘recovery’ appears only twice in the text – once in a document title, and once as a point of tension where harm reduction approaches have to be defended from an attack by ‘the recovery model’. I might have picked this up wrongly, but the implication seems to be that recovery models are part of the problem, something I’ve also heard from some authorities here in Scotland.

The proposed solution – that stakeholders argue ‘overtly, explicitly and strongly for public support and acceptance of methadone as a legitimate and effective form of addiction treatment’ misses the point, in my view, that the prescription of methadone alone will never fulfil that goal, because it’s what goes alongside the prescription that brings positives into lives instead of simply reducing the harms.

I would argue that the introduction of recovery-oriented systems of care, (including medication-assisted recovery as an integrated component), rather than being a threat here, have the potential to transform the structures that have led to this degree of stigmatisation. The absence of hope in treatment systems is not only damaging to service users, but to those working in services. It’s easy to get burnt out. We need to set the bar high not just because we value those we work with, but because we also value ourselves.

I’ll leave you with something hopeful I quoted in a recent blog about stigma.

The most effective strategy for combating opioid use disorder stigma may be to avoid a rhetoric of hopelessness, and instead emphasize the recovery potential of affected individuals and communities.

Perry et al, Addiction, 2020

Continue the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

Paula Mayock & Shane Butler (2021): “I’m always hiding and ducking and diving”: the stigma of growing older on methadone, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, DOI: 10.1080/09687637.2021.1886253

Authors:

NINDS Director Walter J. Koroshetz, NIMH Director Joshua A. Gordon, NIA Director Richard Hodes, NIDA Director Nora D. Volkow, NCATS Director Christopher P. Austin, NICHD Director Diana W. Bianchi, NEI Director Michael F. Chiang, NIDCR Director Rena D'Souza, NIAAA Director George F. Koob, NCCIH Director Helene Langevin, NIH BRAIN Initiative Director John J. Ngai, OBSSR Director William T. Riley, NIBIB Director Bruce J. Tromberg, NIDCD Director Debara L. Tucci, NIEHS Director Rick Woychik, NINR Director Shannon N. Zenk

Inherent in the mission of NIH is that biomedical research and its application can and should benefit all people. Significant events across our nation over the past year and frank discussions in the research community have led to deep reflection at NIH about biases and disparities faced by underrepresented groups in the research enterprise. As we strive to recognize our own role in these challenges, we affirm our commitment to diversity and to positive change to eliminate racism in our community and in our organization.

As a step towards that change, the NIH Institutes, Centers, and Offices that are part of the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research and the NIH BRAIN Initiative, strongly encourage the neuroscience community to take advantage of the new NIH-wide Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation (FIRST) Program, supported by the NIH Common Fund. Although progress has been made to increase participation of historically underrepresented groups in biomedical training stages, members of these groups are still less likely to be hired into positions as independently funded faculty researchers. These populations include underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, individuals with disabilities, individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds, and women.

To help address this disparity, the FIRST program aims to enhance cultures of inclusive excellence through institutional support for recruitment of diverse “cohorts” of early-stage research faculty. Here, “inclusive excellence” describes the cultivation of scientific environments that can engage and benefit from a full range of talent. Neuroscience continues to be one of the fastest growing areas of biomedical research. We want the FIRST program to enable researchers to thrive, and we believe the broader neuroscience community has much to gain. Indeed, the growing field of the Science of Diversity shows the positive impacts that result when heterogeneous teams apply diverse perspectives and expertise to research challenges. We are hopeful that the cohort hiring model in FIRST will succeed in turning the culture in neuroscience departments and their institutions toward greater inclusion and diversity. We fully recognize that there are structural barriers perpetuated by gaps and that critical improvements must be made, because many groups are severely underrepresented in neuroscience. To our neuroscientists: we encourage you to take advantage of this opportunity as a path to meaningful change. We are committed to fostering a more inclusive, equitable, and diverse neuroscience community, and the FIRST program is a step in the right direction, with many, many more steps to come.

The objectives of the FIRST program are twofold: to support institutions in hiring diverse cohorts of early stage research faculty; and to transform culture at NIH-funded extramural institutions by building a community of scientists who are committed to diversity and inclusive excellence. In addition to funds for hiring, the program will support new and strengthened institution-wide approaches to facilitating the success of cohort members and future faculty from diverse backgrounds. For cohort members, this is likely to include mentoring, sponsorship, and networking opportunities. For institutions, this may include training faculty in approaches known to foster inclusive excellence and changing the rubric for interviewing processes. The FIRST program will also fund a coordination and evaluation center, which will develop and guide the collection of common data metrics to rigorously assess the effects of FIRST faculty cohorts and institutional activities on the research culture at funded institutions. Lessons learned by these institutions will be shared with the broader biomedical research community.

The FIRST program is expected to fund 12 awards over the next three years, plus the coordination and evaluation center, with an estimated budget of $241M over nine years, contingent upon the availability of funds. The first receipt date for the program’s funding opportunities is March 1, 2021. For more information, please also view the recent technical assistance webinar.

Related Resources:

Authors:

NINDS Director Walter J. Koroshetz, NIMH Director Joshua A. Gordon, NIA Director Richard Hodes, NIDA Director Nora D. Volkow, NCATS Director Christopher P. Austin, NICHD Director Diana W. Bianchi, NEI Director Michael F. Chiang, NIDCR Director Rena D'Souza, NIAAA Director George F. Koob, NCCIH Director Helene Langevin, NIH BRAIN Initiative Director John J. Ngai, OBSSR Director William T. Riley, NIBIB Director Bruce J. Tromberg, NIDCD Director Debara L. Tucci, NIEHS Director Rick Woychik, NINR Director Shannon N. Zenk

Inherent in the mission of NIH is that biomedical research and its application can and should benefit all people. Significant events across our nation over the past year and frank discussions in the research community have led to deep reflection at NIH about biases and disparities faced by underrepresented groups in the research enterprise. As we strive to recognize our own role in these challenges, we affirm our commitment to diversity and to positive change to eliminate racism in our community and in our organization.

As a step towards that change, the NIH Institutes, Centers, and Offices that are part of the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research and the NIH BRAIN Initiative, strongly encourage the neuroscience community to take advantage of the new NIH-wide Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation (FIRST) Program, supported by the NIH Common Fund. Although progress has been made to increase participation of historically underrepresented groups in biomedical training stages, members of these groups are still less likely to be hired into positions as independently funded faculty researchers. These populations include underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, individuals with disabilities, individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds, and women.

To help address this disparity, the FIRST program aims to enhance cultures of inclusive excellence through institutional support for recruitment of diverse “cohorts” of early-stage research faculty. Here, “inclusive excellence” describes the cultivation of scientific environments that can engage and benefit from a full range of talent. Neuroscience continues to be one of the fastest growing areas of biomedical research. We want the FIRST program to enable researchers to thrive, and we believe the broader neuroscience community has much to gain. Indeed, the growing field of the Science of Diversity shows the positive impacts that result when heterogeneous teams apply diverse perspectives and expertise to research challenges. We are hopeful that the cohort hiring model in FIRST will succeed in turning the culture in neuroscience departments and their institutions toward greater inclusion and diversity. We fully recognize that there are structural barriers perpetuated by gaps and that critical improvements must be made, because many groups are severely underrepresented in neuroscience. To our neuroscientists: we encourage you to take advantage of this opportunity as a path to meaningful change. We are committed to fostering a more inclusive, equitable, and diverse neuroscience community, and the FIRST program is a step in the right direction, with many, many more steps to come.

The objectives of the FIRST program are twofold: to support institutions in hiring diverse cohorts of early stage research faculty; and to transform culture at NIH-funded extramural institutions by building a community of scientists who are committed to diversity and inclusive excellence. In addition to funds for hiring, the program will support new and strengthened institution-wide approaches to facilitating the success of cohort members and future faculty from diverse backgrounds. For cohort members, this is likely to include mentoring, sponsorship, and networking opportunities. For institutions, this may include training faculty in approaches known to foster inclusive excellence and changing the rubric for interviewing processes. The FIRST program will also fund a coordination and evaluation center, which will develop and guide the collection of common data metrics to rigorously assess the effects of FIRST faculty cohorts and institutional activities on the research culture at funded institutions. Lessons learned by these institutions will be shared with the broader biomedical research community.

The FIRST program is expected to fund 12 awards over the next three years, plus the coordination and evaluation center, with an estimated budget of $241M over nine years, contingent upon the availability of funds. The first receipt date for the program’s funding opportunities is March 1, 2021. For more information, please also view the recent technical assistance webinar.

Related Resources:

Event Description

NC DMH/DD/SAS DEI Council Black History Lunch & Learn Series

Be sure to join us Wednesday, February 17th from 12 pm – 1:15 pm for our Black History Month Panel: A Historic Pandemic: Fireside Chat on Leadership Lessons and Reflections with Leaders. Few could have predicted how deeply COVID-19 would upend life and work. Leaders across the globe have had to lead at a time of uncertainty and complexity. We have also learned that a crisis is an opportune time to live one’s core values. Join us for a fireside chat with Black leaders to discuss personal leadership lessons, joy, resilience, advice, and reflections. Click here to join the discussion. American Sign Language (ASL) Interpreters will be present on screen during the webinar.

Event name: A Historic Pandemic: Fireside Chat on Leadership Lessons and Reflections with Leaders.

Event Description

NC DMH/DD/SAS DEI Council Black History Lunch & Learn Series

Learn from one of the leading demographers in the country about the major demographic shifts in NC and the US and their impact on public service systems.

YOU DON'T WANT TO MISS IT!

Event name: Beyond Tuskegee: Historical Medical Traumas as Triggers for African Americans’ Mistrust of Health and Public Service Systems

https://ncgov.webex.com/ncgov/onstage/g.php?MTID=e8e48e69fd631fe271b6026a8fe6f78aa

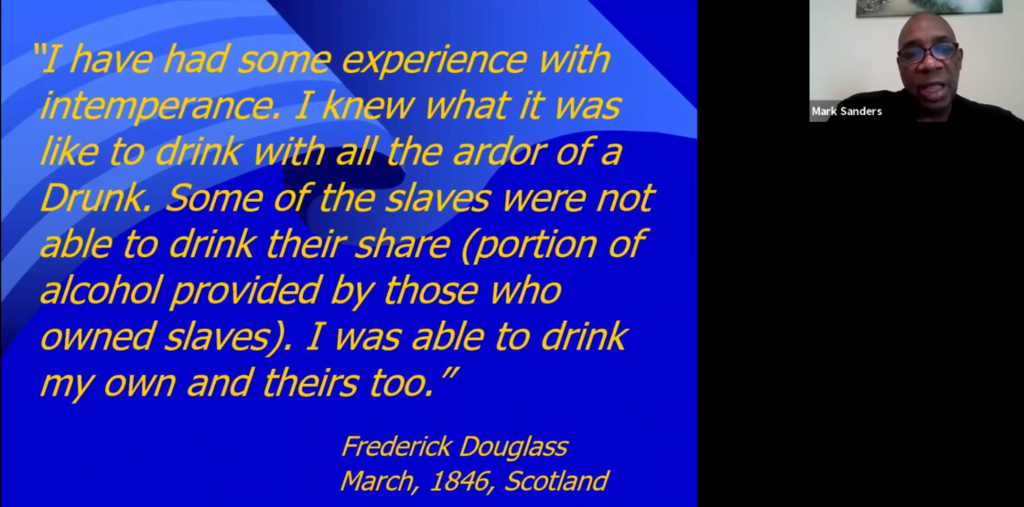

The Association of Recovery In Higher Education recently hosted a webinar on the The Recovery Legacies of Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X.

It was presented by Mark Sanders, an under-recognized treasure in the field.

I can’t embed it here, but please go check it out.

Although the signs are good that journeys to residential rehabilitation in Scotland are about to get a lot easier, there are still some challenges to face. We could quadruple capacity, but if the pathways are not there or blocks exist, more places will make little difference. Not everyone is a fan of rehab and in some areas, gatekeepers seem to hold the keys tightly to their chests, sometimes understandably because allocated resources are scanty, but for other reasons too.

It is unfortunate that because of the neglect of this treatment option and lack of understanding and experience of rehab, we can have people making decisions about individuals’ suitability for rehab who know little of the evidence base, the treatment models available and of the essential features for effective pathways, robust assessment, competent preparation and comprehensive aftercare. To be fair, we don’t have up to date guidance on many of these things, though we are working on that.

This week alone, I’ve heard two stories of anguished families, desperate to find a place in rehab for a loved one, who are facing blocks at every turn despite the release of significant funding for capacity building and placements. Their experiences are, sadly, not unique.

Every couple of years, Phoenix Futures survey service users on their experiences around rehab. Last year they made this public in their Footprints report. The 2020 publication captures the experiences of 70 service users. It makes for difficult reading.

Their clients have complex problems which merit intense and prolonged psychosocial interventions – for instance 70% had had A&E attendances in the previous year, many of them multiple times and more than half had experienced homelessness. Despite this pressing need, half of those surveyed had found it ‘difficult or very difficult’ to find information about rehab and to secure funding.

I had to literally beg for funding

Phoenix service user

A similar proportion found access difficult and almost half waited between 3 and 12 months from expressing an interest to having funding confirmed. All this despite a third assessing that their current health condition was ‘an immediate threat to their life’. And there was evidence that the process was so difficult that it caused a deterioration in their condition.

I found it stressful and humiliating. It led me to start using more heavily

Phoenix service user

As part of the work undertaken by the Scottish Government’s Residential Rehabilitation Working Group, we asked the Scottish Recovery Consortium (SRC) to invite a sample of those with experience of rehab to share their experiences. The summary of their discussions has just been posted on the SRC’s website. I recommend that you take a look at it.

What did we learn from the group? They identified their frustrations at the lack of choice, missed opportunities, late interventions and blocks to referral. They highlighted tortuous funding systems and long waits. They also exhorted us to understand the whole journey and to make everything joined up, instead of having to silo-hop.

We are asked to accept that some people may need more than one rehab treatment because of non-linear recovery journeys. The reference group call for longer stays, enhancements in aftercare and a better deal for families (including identifying issues with being treated too far away) as well as improved communication between stakeholders.

What makes this report particularly relevant is that the group’s appeals for improvement are based on their authentic experiences before, during and after residential rehabilitation. This is what currently happens in our systems. We need to do better.

There is good news too. Like Phoenix Futures, who found examples of good practice across the UK ‘that use psychologically informed processes and models of support that build motivation reduce stigma and facilitate fair access to services’, the Working Group also identified examples of good practice in Scotland, where access pathways were clear and funding straightforward, though these were the exception rather than the rule.

Due to the priority the Scottish Government is putting on improving access to rehab and on removing barriers and building capacity, backed up by significant investment, we can now tackle some of these issues. I hope that in the near future, instead of hindrance, those seeking rehab will find that blockages are removed and are replaced by wide and easy pathways. My hope is that rehab will find its place in an integrated treatment system instead of sitting alone its own silo.

Why is this important? Well, because there is no one-size-fits all answer to addiction – we need all the tools we can get in our toolbox. Rehab has the potential to transform lives and ought to be part of a comprehensive treatment and support system. Those who benefit from rehab (and, not only them but their families too) testify to this again and again.

The rehab saved three lives when they took my son into care; they saved my son’s life who had already been on the edge of death twice, due to drug overdoses. They also saved my wife’s life, and my own.

Father of a rehab client

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

Photo credit: http://www.istockphoto.com/johngomezpix under license

You might not be aware of a podcast called myRecoveryCast.

The episode titled, “NA in Iran Part 1: Visitors” is one of the most amazing things I’ve ever heard. It tells the story of the unprecedented growth of the NA fellowship there, and includes fascinating information and insights.

Aside from the information it contains, I’ve also listened to this when needing some encouragement or hope, or a bit of a lift. It’s truly amazing.

Event Description

Calling all Youth and Young Adults!

COVID-19 has been a roller-coaster ride of events and emotions, with lots of unexpected changes, twists, and turns. If this sounds like a familiar experience– you are NOT alone!

NC DHHS’ Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Substance Abuse Services wants to give teens and young adults like you a place to voice and share your experiences at the Teen Town Hall.

Things you may want to share:

- What has helped you cope?

- What can adults learn from teens and young adults in our community?

- How can we share our resiliency skills with others to help them through difficult times?

Join other teens and young adults, ages 13 to 19, for an open discussion about the impact of COVID-19 on teens, with Kody Kinsley, NC DHHS Deputy Secretary for Behavioral Health and Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Space is limited with preference given to youth and young adults.

Family members/caregivers, providers and professionals supporting youth are asked to take an active listening role during this event, while holding space for youth to engage with one another.

Register Here: https://tiny.one/TeenTownHall-2021

Join the Live Stream Event and chat on the Governor’s Institute’s Facebook Page: facebook.com/GovInst/

Follow the event on the Governor’s Institute on YouTube @GovInst in view-only.

Questions? Contact Kate Barrow, Community Engagement Specialist

Email: Katherine.Barrow@dhhs.nc.gov

Phone/Text: 919-621-1116