by Nena Butterfield, PhD, RN, BSN and Brian Coon, MA, LCAS, CCS, MAC

This post was originally published at the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers (NAATP) website Resources/Blog section on 01/12/2023. It is reposted here with permission.

Initiating and cultivating a participant registry with maximized participation of the persons served requires intentional methodology and consistent attention. For participant registries of people following treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs), the methodology must consider what we know about characteristics of the addiction disease process and effectiveness of the clinical treatment model. SUD treatment providing organizations can seat their participant registries in their treatment practices and embed data collection within a current treatment model. So what does this mean for collecting data, participating in research, and reacting to evidence based findings in the clinical sector?

SUD treatment centers keen to contribute to evidence-based treatment models can integrate data collection into the services they provide, with outcomes of treatment recursive to care, by first adopting a long term model in the form of continuing clinical care, recovery coaching, or alumni support services. These teams serve the recovery support of the person served by completing phone calls to them at specific time increments (e.g. months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 post-acute care) that are fundamentally formative in the person’s recovery trajectory. The service is promoted to the person served from the initial pre-admission pitch of the organization’s treatment model, throughout treatment, and during the exit process.

An organization’s participation in evidence-based research can be presented to potential patients at the admissions and marketing levels as an important asset in the organization’s commitment to informing and implementing evidence based-practices and innovative measures towards improving care. This is a practice and attitude that is widely adopted in primary healthcare and can be spread within the SUD services arena.

The admissions process is an opportunity to discuss with the patient how the organization measures each individual’s progress and treatment outcomes, and how these data are analyzed and used. Organizations can reiterate that this process does not involve any change to the normal treatment plan, but simply allows the organization to make meaning of data that is collected during treatment and continuing care. Clients can be introduced to relevant staff who will be implementing the calls while the person is still participating in treatment. The caller can be introduced to the client as their personal liaison and source of support following completion of the acute-care treatment phase. During the pre-exit process, the participant can be reminded that they will receive calls from their liaison as a normal part of the continuing care model that is committed to the support of the person in their recovery process. The final of the initial touch points occurs when the first call is made by the liaison.

A recipe for success employs fundamental principles of behavioral psychology that reinforce the participant to continue answering the calls and discourages the client from wanting to discontinue the service. Callers should open the call with warmth, a genuine intention to serve, and a sense of authenticity and integrity to gain nothing from the call of personal or organizational benefit. In practice, some aspects of the call should include a friendly and casual tone that inquires after the well-being of the client following listening, and is removed from asking the person formal questions in a rote manner directly from the survey sheet. The caller should prioritize listening, rather, and encourage the client to speak freely and liberally. While listening the caller can glean many of the desired points of information needed to assemble meaningful data. The caller can take notes on unique points of conversation to utilize in future calls to create an environment where the person feels heard, remembered, and prioritized. Notes can be taken on events that arise and are perceived to be problematic and those that are especially effective. Points should be discussed in routine team meetings and incorporated into a flexible and evolving model of data collection and continuing care. Calls should be long enough to gather the necessary information and create a relaxed energy, but not so long the person called feels overwhelmed or fatigued with the process. Research has demonstrated that a call time of 20 minutes or less is generally ideal for achieving those goals.

Creating and maintaining a participant registry that is valuable to informed care can be a simple process with a clear path to success. Leaders can measure incremental impacts of successive changes toward reaching the numeric goal of the desired reach and response rate. Fundamentally, however, if the organization commits to an authentic purpose to serve and improve, to collaborate on a higher level for the greater good of recovery treatment, and tends the garden of participants diligently and with warmth, there will be growth in the field and improvement for the future.

A recorded lecture by the authors of this blog, entitled ‘Using Recovery Management Practices and Principles to Improve Your SUD Outcome Call Purpose and Method,’ is available at the following link.

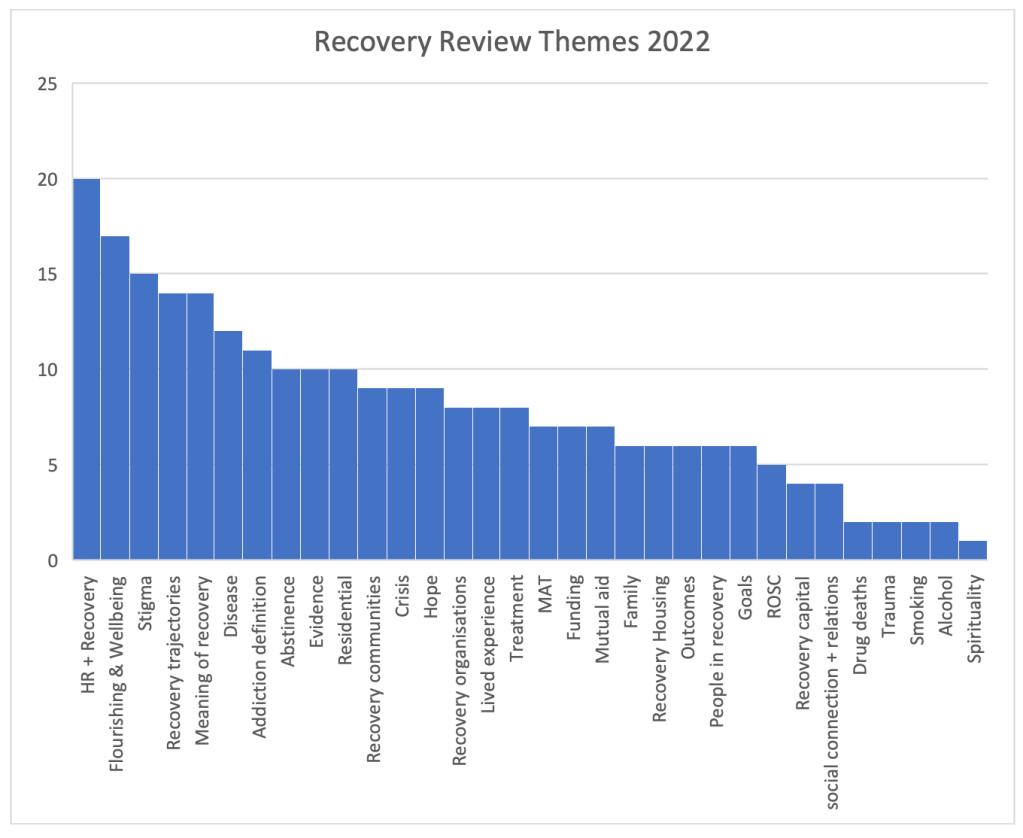

What were the hot topics, burning themes and searing subjects in addiction recovery in 2022? I thought it might be interesting to take a look at the talking points on Recovery Review in 2022.

Although the writers are very different people and we span the Atlantic, all of the contributors to Recovery Review have a keen interest in recovery from addiction and write passionately on relevant issues.

Each blog typically gets read scores of people reading it and often many hundreds – amplified when they are posted elsewhere. I hope that as well as passing on evidence, we also make people think.

So, what were we talking about in 2022 and does that tell us anything about what is really important in the field? More importantly, what’s the relevance to those seeking recovery and those supporting them to move on? I’ve done a not-very-scientific analysis of the most frequent themes across the blogs which is represented in the graph below.

Without doubt, the most commonly recurrent issues were around harm reduction and recovery. While Recovery Review consistently acknowledges the importance of harm reduction and emphasises that there is no need for polarisation, there remain tensions between the two. Many blogs pick this up and examine what those tensions are, how they hold us back and by what means they might be resolved.

Several of us were inspired by Eric Strain’s editorial which highlighted how we let people down when we leave them with “anything less than flourishing”. The concept and importance of flourishing and wellbeing as goals in treatment, support and recovery was the next most prevalent theme.

The issue of stigmatisation of those with addiction was woven through last year’s blogs but also how this can apply those in recovery and sometimes to those of us working in addiction treatment and support who self-identify as being in recovery. This can lead to voices being dismissed and perspectives being judged harshly and in a damaging way.

Although not a new theme, the big-picture perspective on recovery trajectories and longer-term journeys takes us away from categorising treatment as ineffective, abstinence as unobtainable and helps us to address therapeutic nihilism. Better research on long term outcomes for those with substance problems gives us even more hope for those we work with. This was mentioned many times on our blog pages.

Other key topics included the challenges of finding a meaningful and workable definition of recovery that suits recovery communities, treatment and support providers and academics. Recovery as a concept, arguably held most legitimately and strongly by recovery communities and those in mutual aid groups seems to be getting rebranded in ways that make it less meaningful. It could be it is losing its utility (hence the interest in the concept of flourishing).

Tied into this are the next three themes – whether or not addiction is a disease and why that matters, the often unhelpful blurred line between mild and severe substance use disorders and the value or otherwise of having abstinence as a goal.

The remainder of the topics are pretty evenly represented across the year – threads around hope and despair; the opioid crisis; MAT, residential treatment, evidence for recovery; recovery housing, recovery communities and organisations; lived experience; families and the tension between what individuals and families want vs. what’s on offer.

Quotes

Within 2022’s content are so many inspiring and challenging quotes. Some of these are from us and others are from people we are quoting. I’ve selected just a few that particularly caught my attention below.

Our failure to forcefully advocate that patients need to flourish is tacitly acknowledged through interventions such as low threshold opioid programs, provision of naloxone with no follow up services, and buprenorphine providers who only offer a prescription for the medication.

Eric Strain via Bill Stauffer

It seems to me that basing [the designation of addiction] on public reactions is the tail wagging the dog, and that unstable, conflicting messages probably contribute to pessimism and stigma. If that’s true, the best strategy is to just describe it accurately and focus on other targets for stigma reduction.

Jason Schwartz

Though our treatment systems have yet to fully adapt to healing the whole family, most clinicians understand and even stress the relational component of recovery. Obviously, recovery is not, and cannot be solely about the person overcoming addiction.

Austin Brown

Policy has focused on short-term treatment and harm reduction strategies, critical, lifesaving elements of an effective care system, yet we have seen minimal investment in community-based recovery efforts. If we expanded investment in long term recovery in ways that meet the needs of the recovery community, we could save more lives, strengthen families, and heal communities.

Bill Stauffer

If we want to build community-based services that meet the needs of our recovery community, we have to design funding around what works for these communities

Bill Stauffer

Recovery from opioid addiction is also more than remission, with remission defined as the sustained cessation or deceleration of opioid and other drug use/problems to a subclinical level—no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for opioid dependence or another substance use disorder. Remission is about the subtraction of pathology; recovery is ultimately about the achievement of global (physical, emotional, relational, spiritual) health, social functioning, and quality of life in the community.

William White via Jason Schwarz

The linking of abstinence to moralistic and judgmental attitudes and practices plays into culture war battles that consume too much energy and attention within the field.

Jason Schwartz

It occurs to me there may be a relative match or mismatch between the helper’s notion of what addiction is understood to be, and the purpose of the help as defined by the person seeking help.

Brian Coon

Perhaps the most important insight in recent recovery history is that recovery community, through collaborative effort leads to restoration not only in individual lives but supports healing across entire communities, in all their diversity.

Bill Stauffer

It isn’t mercy. If someone genuinely did not choose to do wrong then compassion for that person isn’t mercy—it’s justice. And conversely, if you can only have compassion on someone if you believe she did not choose her misdeeds, then you’ve defined mercy out of existence. You’re not forgiving—you’re saying there was never anything to forgive.

Eve Tushnet via Jason Schwartz

How easily compassionate and well-intentioned responses to addiction can devolve into something that resembles an addiction hospice. And, when we construct addiction hospices, we shouldn’t be surprised that people die.

Jason Schwartz

Here’s to a rich, thought-provoking, enlightening and inspiring 2023 on Recovery Review.

Continue the discussion: @DocDavidM

Photo Credit: d1sk@istockphoto under license

Why can’t they hear anything I say?

How to overcome the challenges of communicating with a loved one struggling with addiction

Communicating with someone you love is not always easy. Too often, conversations end with disagreements, misunderstandings and even broken relationships. If you are struggling to communicate with a loved one suffering from addiction, here are some helpful guidelines that may get your relationship back on track.

Always start with “I love you”

It’s true that “I love you” is one of the most powerful phrases one can say to another. Although it is not enough to cure a loved one of addiction, letting your loved one know that you are coming from a place of love is the best way to start any tough conversation. It assures them that what you are saying is not meant to cause hurt feelings but must be said because you care deeply about them and their well-being. Make your communication direct, honest and most importantly loving.

Acknowledge that you understand what they are going through

Empathy goes a long way when supporting someone struggling with addiction. They may want to quit, but find it’s not that simple. Many factors are at play when it comes to addiction. They may be on an emotional rollercoaster, working through feelings that range from happiness, anger, loneliness to shame and embarrassment. Your loved one may also be facing old friendships that are not conducive to their recovery, challenging their decision to remain clean and sober. Your loved one wants to know that you understand they are having a difficult time.

Set boundaries

It is healthy for your loved one to know your limits: how far they can go with you and how far you will go with them. Setting boundaries establishes that you are willing to support them in recovery but unwilling to engage in enabling behaviors. Participating in a treatment program for family recovery is a great way to discover your enabling behaviors and learn how to set boundaries for yourself and your loved one.

Make yourself available to listen without judgment

This step has two parts. The first is making yourself available to listen, not just to talk. When relationships are strained due to the erratic behaviors of addiction, it’s easy for both the family members and the addict to become dismissive of one another while telling their side of things. However, it is important to know that your loved one needs you to listen and pay attention to their thoughts and feelings. Part two of this step may be the hardest: listening without judgment. Judgement is when you impose your beliefs and values on someone else. It is an act that can shut down communications immediately with you. Remember, criticizing and judging only make someone hurt more and is counterproductive to helping your loved one.

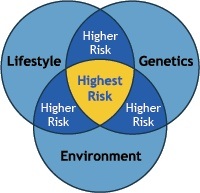

Understand that addiction is a disease

Educating yourself on the disease of addiction will help you keep the emotional or moral perspective out the conversation. Saying things to your loved one like, “Why don’t you just stop,” or having thoughts such as, “I need to fix this for them,” are removed once you understand that addiction is not a behavior problem, but a medical diagnosis just like heart disease or diabetes. It’s a chronic brain condition that causes compulsive drug and alcohol usage despite the harmful consequences it may cause to the user or others around them. Also, understand addiction needs proper treatment for recovery, just like any chronic disease.

Using these steps can help you hone your communication skills and build a stronger relationship with your loved one in a constructive and supportive way.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The post Overcoming Communication Challenges in Addiction appeared first on Fellowship Hall.

Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health were released this week. Here are a few of the highlights.

Substance Use Disorder Prevalence

46.3 million people aged 12 or older (or 16.5 percent of the population) met the applicable DSM-5 criteria for having a substance use disorder in the past year, including 29.5 million people who were classified as having an alcohol use disorder and 24 million people who were classified as having a drug use disorder.

SAMHSA Announces National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Results Detailing Mental Illness and Substance Use Levels in 2021. (2023, January 4).

That’s a startling number. One of every six Americans over 12 years old has had a substance use disorder in the past year?

Further:

The percentage of people who were classified as having a past year substance use disorder, including alcohol use and/or drug use disorder, was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 compared to youth and adults 26 and older.

SAMHSA Announces National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Results Detailing Mental Illness and Substance Use Levels in 2021. (2023, January 4).

So, the prevalence among young adults is worse than 16.5%?!

I found the relevant table and the past year SUD prevalence for Americans 18 to 25 is 18.5% — nearly one out of five. And that’s just past year. It makes one wonder about the lifetime prevalence.

So, what’s going on here?

Well, one factor is the category of SUD itself. It puts the following 2 people in the same category:

- Megan is a 21-year-old whose social life involves drinking with friends every weekend. When she first started drinking she would get very buzzed with 2 drinks but it now takes 4 drinks. On a couple of occasions, due to feeling tired and hungover, she’s called in sick to work and has skipped several morning classes.

- Mark is a 50-year-old man whose polysubstance use started at age 13. By his late teens, his drinking was causing serious problems and had made several attempts to moderate and quit, but was unable to do so successfully. In his early 20s, his drinking was the cause of several breakups with partners he really cared for and caused considerable strain between him and his family. This caused considerable distress — depression, anxiety, loneliness — and he knew his drinking was making all of it worse, but he was unable to stop or moderate. He became a daily drinker and found that he started to feel shaky if he didn’t have a drink or two in the morning. He was arrested for drunk driving 3 times and had difficulty maintaining employment. His 3rd drunk driving conviction resulted in a jail sentence of several months and an alcohol tether upon release. He snuck drinks from time to time and mostly got away with it, but did end up doing a few short stints in jail for probation violations. Around this time he started to develop a problem with opioid painkillers. This problem grew rapidly and replaced his drinking. Eventually, the cost of the pills made them unsustainable and he switched to heroin. He was unable to maintain housing and employment and would alternate between staying with family and staying in shelters. He’s overdosed multiple times, has acquired hepatitis C, and has tried several forms of treatment including residential, buprenorphine, and methadone. He’s now in a hospital for endocarditis associated with injection drug use.

So, SUDs include people like Megan, with very mild problems that many people “mature out” of without any treatment or intervention, and people like Mark, with chronic, severe, and debilitating addictions.

I believe that Megan and Mark do NOT represent differing severities of the same problem. They represent two different kinds of problems. Influenza and lung cancer are both disorders involving the respiratory system, but placing them in the same category would only create confusion. (I’ve written about the problems with SUDs as a category here.)

This isn’t to say that we should just shrug our shoulders about people like Megan, but it does help explain those eye-popping numbers.

Another headscratcher is the increase in the NSDUH’s prevalence estimates over the years. In 2014 they estimated that 8.1% of Americans 12 and older met criteria for a Substance Use Disorder (pg 23).

Recovery Prevalence

The finding that’s getting more attention is about the prevalence of recovery.

Before we look at that number, it’s worth considering what we might mean by recovery.

- Recovery from what? Traditionally “recovery” has been associated with addiction, but not with less severe and acute substance problems. The NSDUH does not make this distinction and, therefore, with cultural understandings of the term.

- Is recovery an identity adopted by survivors of a life-threatening illness that causes serious impairment in multiple life domains and signals connection to a community of others who share the identity?

- Does recovery indicate a way of life that involves healing from serious illness, repairing damage in multiple life domains, restoration of self in personal, familial, and community roles, and a process of becoming “better than well” (something akin to post-traumatic growth)?

- Does it refer to remission, or the reduction of symptoms to subclinical levels? (If so, why use the term recovery rather than remission?)

- Does it describe a clinical endpoint for an illness/disorder?

The report indicates that 7 in 10 (72.2 percent or 20.9 million) adults who ever had a substance use problem considered themselves to be recovering or in recovery.

Again, a stunning number. BUT, it’s worth reflecting on the meaning the key terms — “substance use problem” and “recovering/recovery.”

So, how does the study operationalize these terms? Here are the relevant questions from the survey.

Above, we discussed the problems with SUDs as a category. This question lowers the threshold for inclusion even further. Anyone who does not meet criteria for an SUD but thinks they once had a problem would be included. If the SUD diagnostic criteria are based on beliefs about what constitutes clinical significance, this question includes subclinical levels of use.

The question about recovery is also framed in a way that makes it hard to answer any way other than “yes, I am recovering or in recovery” unless the person is in the throes of a substance use problem.

Megan would answer yes. If Mark were to find his way to recovery and successfully rebuild his life with the help of a community of recovery, would it make sense to put him and Megan in the same category? Where might that be helpful? Where might that be misleading? If recovery is understood as an endpoint and Megan is using alcohol in moderation, could considering moderate alcohol use “recovery” constitute at dangerous goal for someone like Mark?

Imagine the questions asked about disorders affecting the respiratory system. Andrew responds “yes”, that he’s had bronchitis before. Angela responds “yes”, that she’s had lung cancer. For the question about recovery, of course Andrew says “yes” that he has recovered. Angela responds “yes”, that she went through chemo and had a lung removed.

Is Andrew likely to think of himself as “in recovery” or “recovering”? Probably not, but the only sensible answer to the question is “yes”. What do they share in common?

Imagine the question was about weight problems. Bill says yes because his BMI once put him in the overweight category and he shed 15 pounds. Robert says yes because he once weighed 450 pounds and has lost 250 pounds. If we put them together because we assume they share a common experience and identity, how is that likely to go?

It’s important to note that this use of the term recovery is considerably different from its cultural, medical, or research use.

Making sense of all this

So… what should we make of all this?

None of this is to suggest that this information is useless. It could be very helpful for understanding patterns of substance use and conceptualizing public health needs and interventions.

However, I’d urge caution about trying to infer much about the prevalence of serious substance problems and the prevalence of what our culture has understood as recovery.

I also wonder about the effects of this federal survey’s drift (a doubling of SUD prevalence over 7 years?) and repetition of its reconceptualization of “recovery.” How does that change cultural, professional, and personal concepts? Where might that be helpful and unhelpful? What discord does that create? When and where is it desirable and undesirable to create discord? When this kind of work stirs discord between communities, professionals, advocates, and researchers, how should that be navigated? Who decides?

I don’t know, but it’s worth discussing.

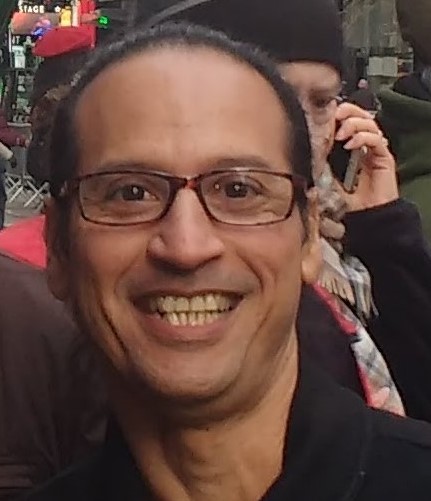

Gee Matamoros’ journey to recovery included some very dark passages. Now he travels a brighter road, and insists on enjoying life as much as possible. Fortunately for us, one of the things he enjoys most is spreading the word about SMART.

In this podcast, Gee talks about:

- How his substance misuse and poor choices landed him in a psychiatric ward

- Why his life was everything to the extreme

- Walking the tight rope of his identity and doing what he was told

- Using substances to cover and sooth impactful moments in his life

- Always running from his authentic self because it wasn’t acceptable

- Finding SMART in rehab, where he could explore other pathways to aid in his recovery

- Sleeping like a baby because of the changes he’s made in life

- How the COVID pandemic helped launch and grow the online Spanish meetings

- What he’s doing now to advocate for SMART and the Latinx community

- Recovery being a community effort – there is support everywhere

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline @ 988, https://988lifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Submit a Comment

Recovery journeys are dynamic, take time and for those who receive treatment, may need several episodes. For some, residential rehab is part of the journey, just as harm reduction interventions can also be part of the journey. However, residential rehabilitation is a complex intervention and complex interventions are difficult to study.

In Scotland, the government is making rehab easier to access and growing the number of beds. This development is not without its critics. Some feel the resource needs to ‘follow the evidence’ – in other words into harm reduction and MAT interventions. This all-the-eggs-in-one-basket position would reinforce the rigid barriers that make rehab the domain of the wealthy or the lucky.

‘Follow the evidence’ in this context is a refrain that implies that there is no evidence that rehab works to help people achieve their goals and improve their quality of life. That is simply not true. Last month saw the publication of a literature review on residential rehab by Scottish Government researchers. It’s a thorough piece of work. This summary of the research evidence provides verification that “that residential rehabilitation is associated with improvements across a variety of outcomes relating to substance use, health and quality of life”.

Rehab is linked to improvements in mental health, offending, social engagement, employment, reduction in substance use and abstinence. There is little research that compares rehab with other treatments delivered in the community, but where there is, the evidence suggests that “residential treatment produces more positive outcomes in relation to substance use than other treatment modalities.” The review also suggests that rehab can be more cost-effective over time than other treatments.

The report also highlights problems and gaps in the evidence base. What happens within the walls of rehabs is diverse and the models and delivery vary, so when we talk of rehab we are not talking about something uniform. We need to gain an understanding about the most effective interventions. Research suggests, for instance, that integrating mental health care into rehab treatment is associated with better outcomes.

The Scottish Government’s literature review highlights gaps that need to be plugged. I think it’s fair to say that there are no queues of Scottish academics curling round the block – researchers chomping at the bit to get their teeth into studies on the place of rehab in treatment and recovery. That we have unanswered questions is not a surprise. Further, it’s important for us to face up to the fact that rehab is not necessarily without risks to individuals, particularly for those with opioid dependence. Those need to be faced square on.

In terms of research, residential rehab, mutual aid, lived experience recovery organisations (LEROs) and community recovery programmes have been largely neglected.

Indeed, the perception of such risks may be one of the main reasons for resistance to rehab as an intervention. We don’t know if those going to rehab in Scotland have higher mortality than in other kinds of treatment, but there is evidence from elsewhere that this could be the case. However, it is plausible that people with higher problem severity (and higher risk of death as a result) end up in rehab. The mortality rate in intensive care units is higher than in general wards, but we don’t stop people going to intensive care because of that.

We also need to be aware that there are mitigations that can be employed to reduce risks. These may include things like comprehensive aftercare, re-titration of those who want to leave treatment early and rapid re-entry into prescribing services if individuals return to use.

Recovery housing, take-home naloxone, overdose prevention, assertive referral into recovery community resources, outreach and recovery check-ups may also reduce risks. Standards could be developed to encourage the adoption of such practices. The impact of these have not been tested in research, but they could be.

I don’t believe it is in the interests of those individuals (and their families) who struggle with dependence on substances for us to maintain treatment turf wars. We can have harm reduction and recovery. We can have MAT and abstinence. We can have outpatient treatment and residential rehab. Whatever we have, it needs to be plugged into supports across housing, criminal justice, benefits, education, training and employability and health. A joined-up, comprehensive treatment system with strong links between its component parts will serve individuals best.

We don’t need to say one thing is better than another, but we do need choice and through shared decision making we can try to help patients align themselves to a treatment option that helps them meet their goals. And we need to be humble too. Evidence suggests that over a lifetime, most people resolve their problematic use of substances. When they look back, they may be grateful for the part that treatment played in their recovery, but it is likely that it will be only one of many factors that helped.

For the moment though, we can certainly challenge the voices that say ‘there’s no evidence that rehab works’, for there is ample evidence that it does. I’m not unrealistic about this though. As I’ve been writing, I have been mulling over the wisdom of Ahmed Kathrada’s observation: ‘the hardest thing to open is a closed mind’. That shouldn’t stop us trying.

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

I watched an informational video about search patterns used by the Coast Guard and gained some thoughts I decided to share. The video was just under 30 minutes long and you can find it right here if you’re interested.

As you read this article, see what you notice from outside our field that could serve as hints to help improve our clinical work as addiction professionals.

What are we looking for and where is it heading?

The video I watched showed how Coast Guard search and rescue teams vary their search patterns and their use of search assets (ships, planes) according to:

- the type of object they are looking for;

- the size of object;

- the height and amount of visible surface area of the object above the surface of the sea;

- and “drift”.

As an example, they noted a person wearing a life jacket will float differently from a disabled flat-bottom boat.

Interestingly, they said that drift of the object will vary according to the total of the ocean current at the surface, the deeper current, and the wind. And they clarified that the different currents and wind might each be flowing in the same direction, or different directions.

To me all of that was fascinating and I started to consider possible areas of application for our work. Among other things, I asked myself things like: “As addiction professionals, what is it we are looking for and why? And where is the patient heading?”

Is our work complicated enough? Are we letting science help us?

The search crew stated that all the relevant data about the different currents and the wind are put into a computer. And the software then generates a tailored search pattern for that specific scenario. And the pattern is given to the air assets, ships, and personnel conducting the search.

- They stressed that different things float differently, and the atmospheric and ocean currents and conditions also differ.

- And they stressed the fact that all the relevant Coast Guard staff experience standardized training, so they will all understand the same things and follow the same procedures.

Again, I started to think about our work. Among other things, I wondered if we have made our work complicated enough, and if we as a field are really letting science help us like we could.

Best-practice, structured methodology? That also champions the patient?

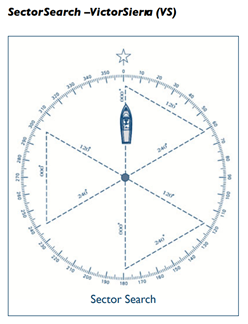

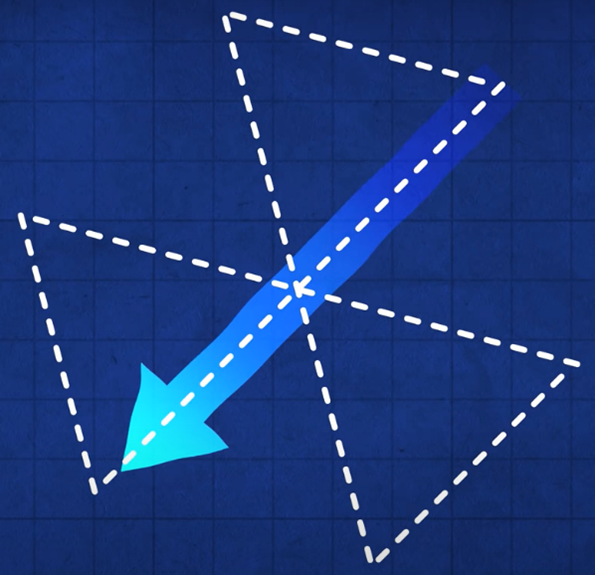

In the video, the “Victor Sierra” search pattern was featured.

The Victor Sierra search strategy is used to look for a small object in a relatively small location where the probability of the object being within that location is relatively high. The pattern is built from 3 isosceles triangles. It was initially odd to me, but rather interesting.

https://ccga-pacific.org/files/library/Chapter_9_Search.pdf. Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

During the use of the Victor Sierra search pattern, one of the crew is assigned to look out the left side of the vessel, one the right side, and one out the front – visually covering the entire search area in a thorough and reliable way.

But before the search begins the direction that the object is moving in is determined. And the direction is determined from the combination of the wind and both shallow and deeper currents.

That combination is used to understand the movement of the object being searched for, and also for a buoy they call the “datum”. The datum is placed in the water and left free to float and move on its own according to the wind and currents – just like the object being searched for.

The word “datum” is fascinating to me because it indicates a single reference point. The presenter noted that in engineering “datum” is the reference point from which one measures other things.

http://wow.uscgaux.info/Uploads_wowII/070/SEARCH_and_RESCUE-A_Guide_for_Coxswains_May_2020.pdf Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

But in this case the datum is literally a moving thing, not a fixed or stationery thing. And its motion (direction and speed) are the sum of the wind, shallow current, and deep current.

They went on to say that the search vessel’s initial motion is always in literal line with the movement of the datum.

Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

Interestingly, once the datum is deployed in the water, the ship backs away from it – in order to not effect it or its movement. The angles of the search pattern are then followed at a fixed rate of speed, at a set distance for each, and completed in a certain order.

As I watched the video, I saw many metaphors related to our work. And I asked myself many questions. For example, “Do we have a nationally-normed, universally applicable, best-practice structured methodology to guide us? One that champions the patient as the center?”

How person-centered are we?

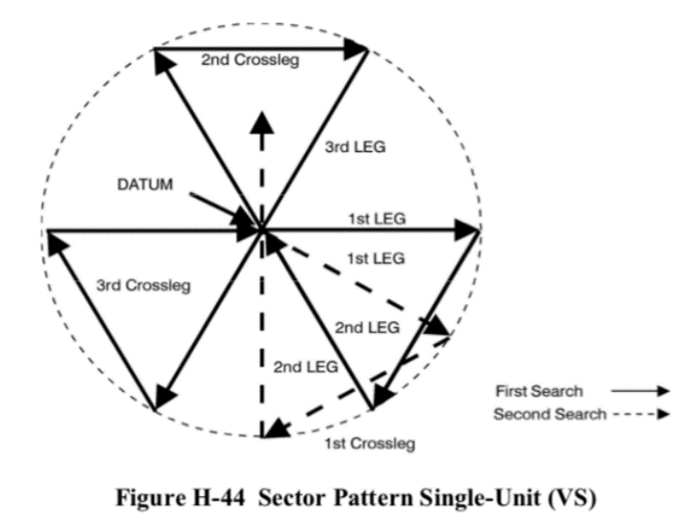

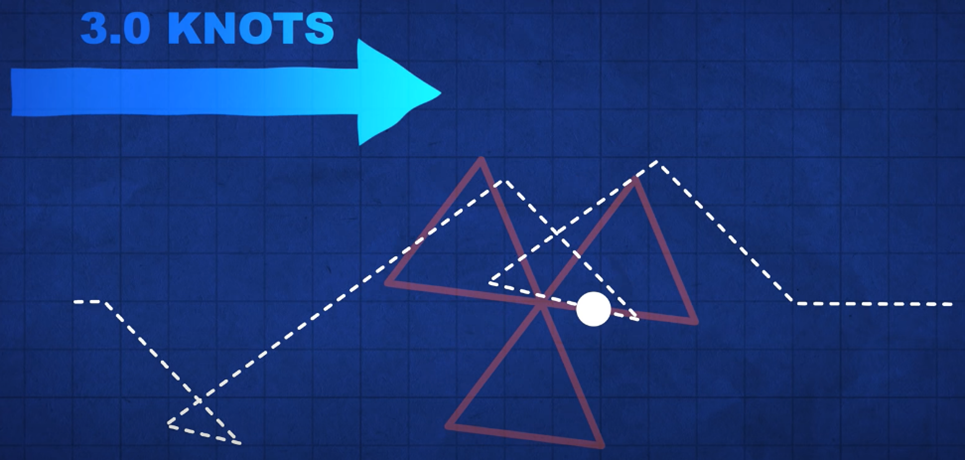

Interestingly, the order in which the segments of the search are completed is static, but that order does not complete one full triangle at a time.

How is the search pattern followed?

- The first leg of the search starts from the location of the datum and is in the direction of the wind/water as crew can best determine.

- Once that first leg of the search is completed, the next angle is calculated from the location of the end of the first leg.

- Following the completion of this second leg, the ship heads directly back to the datum, and this is not done on a preset or calculated heading. Rather, the crew visually locates the datum and drives straight to it.

- Once they physically reach the datum, the direction/degree/angle of the next leg of the search is then determined.

As the search proceeds in this way, the search pattern is kept integrous by repeatedly returning to the datum, rather than making successive calculations from calculated locations. And in this way each new search angle moves with the natural combined movement of the wind and water.

I personally found the level of structured methodology and intentional freedom in the planned work they describe greatly inspiring.

And I asked myself if it is realistic to anticipate in the future:

- a universally available set of best-practice structured methodologies;

- that champion the patient;

- created for us on a normed basis;

- and specifically tailored to the particulars of the current person and their situation.

I ask myself if we are willing to be guided in the most expert way possible?

Messy inconsistency or a combination of expertise and natural forces?

Given drift, the lines that are ultimately searched do not form triangles. This is because the search lines move in time, congruent with the buoy.

By contrast, if the buoy did not move, the course of the search craft would simply replicate the pre-set triangular pattern. But it never does. The actual final shape of the search pattern is non-intuitive and always reflects the actual current/wind.

The shape of the search pattern will differ with the rate of the drift. The search moves with the current.

- For me, the wind is the manifest content of the life of the patient.

- And the water current is the latent content of the life of the patient on both shallower (more accessible) and deeper (less accessible) levels.

- And for me, the buoy reminds me of the person we are searching to help – who is always moving and provides us our center of reference.

This portion of the video made me wonder if we should consider a return to that center each time we complete our immediate purpose, and before we chart our next clinical move.

And it made me think about how our work appears from the outside. For example, does such work reflect messy inconsistency when viewed from the outside? Or does our work trace the combination of expertise and natural forces when viewed from the inside?

Appreciating drift, rescue, and what comes after rescue

The Coast Guard staff informed the film maker that wind and water are often aligned differently or may even be in opposition. They noted that these may all differ from each other due to the differing forces that produce each of them separately. To me, that fact alone is interesting and informs our work.

And they added that the most important task is the first task – determining the “set” and “drift” of the buoy. They stated that “set” refers to the direction of the buoy and “drift” refers to the speed of the buoy.

Once the starting center point of the pattern is established, the direction for the first leg of the 3 triangles is determined by going with the elements, not against them. They also stated that once the speed of the craft is set, it is not changed. Rather they, “Let the current take us.”

- To me this shows us the value of person-centered methods.

And to me this illumines areas of possible struggle for professional workers in our field. For example, do we choose:

- the datum (strictly person-centered reality) as our only reference point;

- the lighthouse that we might need to move toward once the rescue has been accomplished as our reference point; or

- the north star of long-term improvement as our reference point?

Which reference location do we use in the current moment? Or should we combine reference locations? Or at times oscillate between them?

For our work, would we only and always choose the location of the datum as the imagined destination of “full recovery 5 years after the last clinical touch”? Or should we always and only place it and leave it at the epicenter of the person served?

Or could the location of the datum be different, at different times, for different or changing purposes?

- If the epicenter of our work is the person served, then the patient is the reference point.

- If the epicenter is an imagined and much-fuller quality of life, is our effort meaningfully sufficient using that and only that long distance improvement as our only reference?

- But even then, who should define the hoped-for final location, and when, and on what terms?

And speaking of location, what about wind, shallow currents, and deep currents – at the location of the patient’s home or newer waters once they arrive safe? Are we also building safe-harbor locations in our society and larger communities? Do we appreciate all three of: drift, rescue, and what comes after rescue?

Science and compassion?

To conclude I’ll say that I imagine clinical work that includes:

- inputs from the patient, family members, clinical workers, and research scientists;

- reference points including the current condition of the person we serve contextualized by environmental conditions as they are;

- incremental markers to a safe harbor; and

- much farther true-north type wellness goals.

And I imagine our work both moving toward, and rotating on or pivoting against, pairs or groups of these markers (rather than only using one passive reference point) in best-practice algorithms, as we proceed.

Bob Lynn has summarized his aim for our work as “science and compassion”.

Hopefully this article has presented a framework and some considerations inspiring addiction professionals toward that aim.

Suggested Reading

Behavioral Health Recovery Management: A Statement of Principles.

Hofmann, S. G. & Hayes, S. C. (2018). The Future of Intervention Science: Process-Based Therapy. Clinical Psychological Science. 7(1): 37-50. doi.org/10.1177/2167702618772296

Proctor, S.L, Llorca, G.M., Perez, P.K. & Hoffmann, N.G. (2016). Associations Between Craving, Trauma, and the DARNU Scale: Dissatisfied, anxious, restless, nervous, and uncomfortable. Journal of Substance Use. DOI:10.1080/14659891.2016.1246621

The first major effort to define recovery in America was in 2007, when the Betty Ford Foundation, now the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation published What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. The paper noted that “recovery is a voluntarily maintained lifestyle composed characterized by sobriety, personal health, and citizenship.” Our understanding of the continuum of substance use, from social use without consequence to addiction has improved significantly in the years since it was first published. A myriad of recovery definitions of recovery have been penned as our understanding of the dynamics in play have improved. As a house divided, none have achieved broad consensus.

Copious amounts of ink have been spilled in academia over the years on defining recovery. The defining of recovery has become a cottage industry, everyone seems to have a different one, none of which broadly resonates across our society. This is a matter of deep contention an increasingly a front in our larger culture war. It is a formidable barrier to forward progress. As Bill White noted in Addiction Recovery: Its Definition and Conceptual Boundaries has consistently failed to achieve consensus, is not just an academic question, but it has economic and political context as industries have formed around harm reduction, addiction prevention, treatment and recovery support. We are awash in definitions that have become increasingly broad and used to define any positive outcome for any person experiencing any form of substance misuse. How you define recovery is almost like a Rorschach test on where you stand in respect to your experience of substance misuse and your orientation to any of the related fields of interest.

Science is revealing that resolving a substance use condition is quite nuanced, even as we increasingly lump all of what can occur in respect to healing under the term recovery. This last point will inevitably create additional challenges in how the general public understands substance misuse and its spectrum of resolution. It may serve us well as this juncture to assigning the spectrum of resolution of varying severity or forms of substance misuse distinct terms in order to assist society in understanding the complex dynamics in play across the continuum of healing. A taxonomy of healing.

NIDA had taken an all-encompassing strategy to define all resolution under the term recovery. In its 2022 to 2026 Strategic Plan, NIDA notes that “Recovery from SUDs means different things to different people. Broadly speaking, it is a process of change through which people improve their health and well-being while abstaining from or lessening their substance use or by switching to less risky drug use. For some, this may mean complete abstinence; for others, recovery could be ceasing problematic drug use, developing effective coping strategies, improving physical and mental health, or experiencing some combination of those or other outcomes.”

The NIDA strategic plan is reflective of our current scientific understanding of the continuum of substance use from non-harmful use, through misuse to severe substance dependence. Severe SUD typically leads to loss of control. For those of us whom who experience it, refraining from all use is often indicated. It is not an uncommon experience for persons on the far end of the spectrum to die attempting to moderate their use in the way that a person with a less severe form or one in an earlier stage of progression can manage with moderation efforts. It is important to remember that point.

NIDAs approach is consistent with the most recent definition of recovery from NIAAA. “Recovery is a process through which an individual pursues both remission from AUD and cessation from heavy drinking. Recovery can also be considered an outcome such that an individual may be considered ‘recovered’ if both remission from AUD and cessation from heavy drinking are achieved and maintained over time. For those experiencing alcohol-related functional impairment and other adverse consequences, recovery is often marked by the fulfillment of basic needs, enhancements in social support and spirituality, and improvements in physical and mental health, quality of life, and other dimensions of well-being. Continued improvement in these domains may, in turn, promote sustained recovery.” It includes cessation of heavy drinking as characterized by drinking no more than 14 drinks a week as recovery if sustained over 90 days.

My own views on recovery have certainly evolved, although it also true that the first definition of recovery from Betty Ford is the one that resonates the most deeply with me. I am grateful for this space at Recovery Review for those sharing views and challenging our collective thinking. In Mid-December, Brian Coon posted How Helpful is the 2022 Definition of Recovery from the NIAAA? His overall perspective is favorable. He noted that he liked it for several reasons including that it seems to hold space for harm reduction approaches, incrementalism of long/slow change, and addressing people at different stages of change, and of treatment, on a per-problem basis.

A few days later, Jason Schwartz posted More on the NIAAA definition of recovery. His post links this NIAAA Webinar: Using New Definitions and Tools to Support Alcohol Recovery. Jason notes that he has some dissonance with it and describes how recovery has cultural and well as scientific connotations and that people in recovery can and do develop a recovery identity. He asks if it make sense to develop research definitions that create discord with cultural understandings (even if their boundaries are poorly defined). He explores the discord and considers how research and cultural understandings interact and influence each other when there are such rifts.

This dissonance plays out with vitriol in the harm reduction, treatment, and recovery support space. People calling those who have pursued full abstinence in order to not die from addiction as elitists. On another “side” there are still far too many people in abstinence-based recovery who continue to view any properly taken medication as inconsistent with recovery despite all the evidence to the contrary. Our lack of consensus-based terms to describe the resolution of substance use conditions across a continuum of severity and type are at the heart of much of the conflict.

Drug policy, including the defining of recovery is now a front in our larger culture wars. Jason highlights this in his recent piece Liberalism? Or libertarianism? There has been public backlash to these approaches. Under the NIDA definition, a person using a clean needle to use drugs may be considered to be in recovery as they are reducing the risk of infection. While polices that seek to keep people alive and improve their overall health are certainly evidenced based and a good thing to be embraced, I don’t think our society is at the point in which using a clean needle is equivalent to the types of systemic changes people in more recognizable recovery undergo. Low threshold engagement and harm reduction efforts make sense and should be expanded but lumping it all under the term recovery is a bridge to far.

From a 50,000-foot level, this is causing our collective interests a great deal of harm. We can ill afford the polarization of the stakeholder groups interested in saving more lives from the impact of substance use across our communities. We need broad consensus that bridge the gap between the scientific and society. We must bridge science and culture to move forward with a nuanced taxonomy that describe reduced risk stages and forms of substance use resolution.

Lumping all change under the term recovery obscures our capacity to understand the continuum of SUD resolution. The term was historically embraced to express the experience of persons with the most severe forms of substance use. A term indelibly linked to the kind of lifestyle that hundreds of thousands of people like me with the most severe form of substance use experience, which includes no recreational or misuse of substances as a life sustaining imperative.

How does this differ from an interventional or process of changes people undergo from a less severe form of the condition? What we call things matters and improves our capacity to positively affect change.

From a science perspective:

- How would a more nuanced model of substance misuse resolution inform work done in the field?

- Can we develop more granular understanding of resolving a substance use condition in order to provide better weatherproofing for recovery remission?

- What course of strategies would recommend to a person based on the severity of their presenting condition if we could articulate it better and work to understand individual risk factors and level of recovery capital?

From a cultural perspective:

- What value would a consensus definition of the continuum of substance use and the resolution of a substance use condition have for our whole society?

- How can improved insight and more concise definitions of resolving a substance use condition support better targeting of interventions earlier in problem resolution?

- What can we learn from the past about the collective outcome of all of our infighting?

We should stay consistent with the historic use the term recovery to describe those who have found resolution of a severe form of the condition requires cessation of use and systemic life changes. We can then describe the resolution of less severe forms consistent with both our scientific and broader cultural understanding of what this looks like and under which conditions and for whom moderation or other interventions may be an effective healing strategy.

It is an imperative to develop a conceptual SUD healing framework with broad consensus. To assign the resolution of a substance problems of varying severity and type distinct terms within a taxonomy of healing. It would help us understand the complex dynamics involved in resolving a substance use condition. For policymakers and researchers out there for whom this resonates, perhaps it is time to convene a focus here and take action.

For those of you who may disagree, I hope you continue the dialogue in respectful in open ways in order to assist all of us in developing a conceptual framework that fosters broad consensus and greater public understanding of the complexity of substance use conditions and their resolution.

While challenging, the prize is well worth the effort.

The New York Times published a guest essay this weekend challenging the disease model of addiction.

I’ve read several similar pieces over the years and frequently have the same experience. I agree with most of the writer’s points, but disagree with his conclusions.

Let’s walk through it.

Annual U.S. overdose deaths recently topped 100,000, a record for a single year, and that milestone demonstrates the tragic insufficiency of our current “addiction as disease” paradigm.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

The drug death rate is very troubling and discouraging. If we were to add deaths associated with tobacco and alcohol, it’s much worse.

This strikes me as evidence for the insufficiency of our interventions to prevent and treat addiction, and/or the insufficiency of our systems to deliver those interventions. It does not strike me as evidence that it is not a disease. If COVID, type 2 diabetes, or asthma are associated with a large death toll, is that evidence that they are not diseases?

Thinking of addiction as a disease might simply imply that medicine can help, but disease language also oversimplifies the story and leads to the view that medical science is the single best framework for understanding addiction. Addiction becomes an individual problem, reduced to the level of biology alone. This narrows the view of a complex problem that requires community support and healing.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

This portion starts to illuminate the disagreement between me and the writer.

He’s concerned that too many people believe biology and medicine are the only frames we need. Further, he’s troubled that this might lead to interventions that target only individuals and omit social interventions.

I share those concerns.

However, I don’t see this as reason to doubt the disease model.

I believe asthma is a disease and environmental interventions are important. In the case of asthma, climate change might be a reasonable target for intervention. I believe type 2 diabetes is a disease and community-level interventions are critical. COVID is a disease and individually targeted interventions are clearly an insufficient response. I also believe depression is a disease and interventions targeting social support will be essential for many patients.

I also believe that behavioral interventions are essential for responding to all of these diseases and many others.

My experiences and those of my patients seem more in line with how 16th- and 17th-century writers described addiction: a disordered choice, decisions gone awry.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

If we view addiction as a brain disease, I don’t see how disordered choice is incompatible. Choice occurs in the brain. One could argue that other diseases involving the brain (depression, bipolar, schizophrenia, OCD, etc.) also result in disordered choice.

[Benjamin Rush] was famous for describing habitual drunkenness as a chronic and relapsing disease. However, Rush argued medicine could help only in part; he recognized that social and economic policies were central to the problem.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

This is a better understanding. It might be worth asking how to restore and protect that broader understanding.

The author points to a history of using the disease model (or beliefs associated with the disease model) in ways that are racist. All of this history is true and important, but it doesn’t really say anything about whether addiction is a disease. COVID was racialized, particularly early in the pandemic, but this is not grounds for reclassification of COVID.

The author continues addressing social justice issues in responses to the drug problem and raises another important consideration:

Not all drug problems are problems of addiction, and drug problems are strongly influenced by health inequities and injustice, like a lack of access to meaningful work, unstable housing and outright oppression. The disease notion, however, obscures those facts and narrows our view to counterproductive criminal responses, like harsh prohibitionist crackdowns.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

I see how a narrow medical/biological framing of disease can obscure the roles of inequities, injustices, and oppression. I also see how blindness to those factors could lead to criminalization. However, a disease model, at worst, cuts both ways. A deterministic view may contribute to prohibition and criminalization, but a model that locates addiction, not in the drug, but in the interaction between the brains of certain users and the drug, might push in the other direction.

The important point he raises here is that “not all drug problems are problems of addiction”. To be sure, addiction constitutes a relatively small fraction of all drug problems. It would be both incorrect and harmful to classify non-addiction drug problems as a disease. This is a critical point that, to me, reinforces the need to clarify the boundaries of addiction and distinguish it from other drug problems that are not a disease.

In contrast, today, descriptions of “brain disease” imply that people have no capacity for choice or self-control. This strategy is meant to evoke compassion, but it can backfire.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

No thoughtful expert would suggest that people with addiction have no capacity for choice or self-control. However, the author previously stated that a “disordered choice” model resonated with his experience, which fits well with the impaired control described in definitions of addiction that frame it as a disease.

The public responses that the chronic brain disease model evokes are complicated. (It may evoke less blame but more pessimism.) It seems to me that basing its designation on public reactions is the tail wagging the dog, and that unstable, conflicting messages probably contribute to pessimism and stigma. If that’s true, the best strategy is to just describe it accurately and focus on other targets for stigma reduction.

The author closes with reflections on the incompleteness of the disease model.

I am in full agreement that a narrow medical/biological disease model is incomplete, inadequate, and will lead us in the wrong direction with respect to prevention, treatment, and policy. The author is a physician and have a lot of respect for a professional that seems to be saying that his discipline can only hope to be a part of the solution to the problem.

However, I don’t believe the problem here is that “disease” is the wrong category for addiction. The problem is that too many people think of disease in narrow medical/biological terms. This was addressed in the landmark 2000 article, Drug Dependence, a Chronic Medical Illness, which argued that drug dependence is comparable to type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and asthma when considering the roles of genetic heritability, personal choice, and environmental factors, as well the etiology and course of all of these disorders. Chronic diseases are generally complex in their etiology and in what’s required to effectively treat and manage them. The kinds of complexity present in addiction are more the norm for chronic diseases rather than the exception.

Recent years have seen increased interest in social determinants of health (SDOH), which serve the purpose of filling in the rest of the picture in terms of etiology and treatments/interventions.

Surprisingly, even genetic counseling offers insight into social and environmental factors that influence the onset and course of heritable illnesses.

So… is it misleading to call addiction a disease? Only if your understanding of disease is too narrow to allow for the complexity of chronic diseases and social determinants of health.

I think the solution is that we get better at talking about diseases and their complexity, rather than reclassify addiction because it’s too complex.

Someone relatively new to the substance use disorder area asked me recently why I thought there was so much division and hostility in the addiction and recovery field, compared to other parts of health and social care. Do we really have more conflict than in some other healthcare areas? There are strongly held positions which seem impossible to reconcile in all areas of life. Is addiction policy, advocacy, treatment, support and recovery any different?

After nearly 20 years of working exclusively in this field, my conclusion is that it probably is different. This is certainly something to be curious about. At the outset I want to be clear: I also believe that there is plenty of harmony too – much that binds us together and some great examples of collaboration in the interests of the people and families we are trying to help.

Some of the division is between harm reduction and recovery or, more precisely, around harm reduction, medication assisted treatment, and abstinent recovery. A great number of people have called this out as a false division, urging us toward a broad range of responses centred on people’s needs in the here and now and guided both by evidence and individuals’ rights to choose the recovery path that is right for them. Sometimes those voices are drowned out by polarising dissent.

Every week I hear strongly held perspectives on one side or the other of these fissures. Sometimes the antagonism to a particular approach is more subtle and we see exclusion and attitudinal barriers rather than overt criticism. At times we can tell more about an organisation’s or individual’s approach by what they don’t say.

For instance, in some circles the words ‘recovery’ and ‘abstinence’ are rarely seen or mentioned despite being important to some people trying to resolve their substance use problems. Similarly, other people consider opioid substitution therapy to be simply replacing one addiction with another, despite compelling evidence of reduction of harms. Pressure can be put on people to detox without adequate preparation, supervision or supports in place creating avoidable risks.

The question about the vigorous level of debate and fiercely held opinion we experience in the domains of addiction, treatment and recovery is a good one without a simple answer. I’ve been thinking about this since and here is my tuppence worth.

We are passionate

Many of us who work in addiction treatment are impassioned about substance use disorders and the responses we have to them. This passion is driven by personal and professional experience, by hope and as a response to the grim drug and alcohol deaths we see. Such passion drives beliefs and actions and can lead to progress and improvement in the lives of individuals. However, sometimes passion can be enacted as anger or arrogance. It can spill over into wrath or rage. On occasion, it can disguise fear.

These experiences which drive passion can be self-defeating or limiting. If you have made an abstinent recovery aided by 12-step fellowships, you may come to believe that this is the only way to recover – though, to be fair, many people in mutual aid groups will readily acknowledge that there are multiple pathways to recovery. Similarly, if you are not seeing evidence of people moving on to abstinent recovery and of them leaving treatment settings, you may believe that people do not recover or that it is much too dangerous to support such a path.

Then there is the danger of zealotry, driven by passion or fear – a blinkered approach which will not, or cannot see that we need a broad and welcoming church – a place that celebrates diverse approaches and pathways. When contempt for others creeps in, often unbidden, we diminish our effectiveness and authenticity.

This week in a newspaper I read an article where one treatment service explicitly undermined others, using misleading words. The effect was to distance the reader from some of the other good points made. The unintended consequence was disconnection, further division and a lack of positive impact. While we don’t need uniformity and we need to have the capacity to call out wrongs, we also need mutual respect. It’s a good value to hold close.

You can have no influence over those for whom you have underlying contempt.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

My fellow blogger Bill Stauffer recently noted that social media may not help us here. We connect with others who hold the same views as us and end up with confirmation bias or we get swept up in the wave of righteous indignation and then write things that are disrespectful, rude, or even threatening.

As a relative newcomer to Twitter, I was naïve enough to be shocked initially by some responses to my early posts and to what I saw as the reasonable perspectives of others. I follow many whose views `I do not agree with, but read what they post with interest, however I don’t tolerate abuse. We behave differently online than we do in person and indeed, social media may actually harm our emotional health. I am grateful for the mute and block buttons – wonderful inventions.

We are concerned

If we see our clients/patients dying of drug and alcohol-related causes when they do move out of treatment, we may think that it is too risky for anyone ever to move on. For those of us who work in addiction treatment and support, hearing about overdose and death is a chilling, upsetting and unwelcome part of the job. But being excessively worried and anxious about the safety of those we are trying to support can lead to unhelpful consequences.

Without adequate supervision and support we can begin to live with unrelenting and harmful levels of concern. Then we can begin to get burnt out or develop dysfunctional thinking and behaviour.

Concerns about detox and abstinent recovery need to be addressed, as do those around MAT and harm reduction. Myths need to be put to bed though. Reassuringly, there are plenty of practitioners who have reconciled those concerns in a way that allows them to work passionately across all areas, mitigating risks but not in a way that stymies the capacity of people to achieve their goals. I am in awe of some of them.

We have limited resources.

When funding is tight and demand is high or services are threatened, we can reflexively respond in defensive ways, or even attack others’ services. I’ve certainly experienced that in the past – people who are normally supportive behave in ways that are difficult to understand and everybody feels hurt and upset.

When resources are limited, you get people fighting their corner, but this can spill over into arguments about which services should be limited, have resources removed or be shut down. Think residential rehab for instance – often cited as ‘not evidence based’ by those who put their faith wholly in medical models, they can be seen as low hanging fruit when money dries up. I’ve experienced this more than once.

We get disenfranchised.

The reason we have a surge in advocacy and support for people with alcohol and drug problems is that they have not felt represented by the services set up to help them and have not felt that those services have met their needs. They have not had a voice. Or just as bad, when that voice speaks up, it is ignored, dismissed or treated with contempt. Perhaps, worst of all, individuals can sometimes be given a tokenistic place at the table – present but powerless. While huge power disparities persist, it is always difficult for lived experience to have any impact on policy and the shape of services.

Now when voices are beginning to be heard – and in Scotland those voices are likely to become more powerful and influential through the forthcoming National Collaborative – they can feel threatening to the establishment. Yes, we have our evidence that we base our treatment offer on, but now we have new evidence of a bit of a mismatch between what we have on offer and what individuals and their families want from treatment. We have a distance to go to achieve balance.

There are those who would shut those voices down, but the likelihood is that, in terms of visibility and volume, in the future lived and living experience is not going anywhere but up.

I will ensure that local panels of people with lived and living experience are involved in all local decision making, and that a national forum or collaborative is in place to better inform our national mission.

Angela Constance, Drugs Policy Minister

We lack the breadth of experience

Years ago, a colleague who had worked in the field for years told me he’d never met anyone in long term recovery from heroin addiction. At that point, I’d met hundreds, so we could agree that we’d had very different experiences – poles apart. If professionals don’t get to see sustained abstinent recovery, instead seeing people remaining in treatment for many years or indeed experiencing too many deaths of clients or patients then of course it’s going to feel pretty risky to support people to the goal of moving out of services all together.

Equally, although I now work in residential rehab, working in harm reduction and medication assisted treatment settings in the community has helped me see the need for a broad spectrum of approaches to help individuals achieve their goals. Recovery is dynamic and non-linear and needs flexible and wide-ranging approaches to support it.

We are all a little prone to suffering from the Dunning Kruger effect, a cognitive bias where we think we have more knowledge and skills than we actually do on an issue. If all practitioners got to spend some time in different settings (from injecting equipment provision and wound care through to community and residential services and get a robust introduction to community recovery and support resources) then we’d perhaps seen more harmony and mutual respect.

We don’t always know ourselves

We go into caring roles for a variety of reasons and not all those reasons are apparent to us as individuals or to others. For some of us, growing up with addiction in our families can lead to a healthy desire to help other families. For others, unresolved wounds and conflicts from early life can hamper such efforts. We may not have tended to those early wounds or even be aware that they are still tender and are influencing our behaviour in the here and now. Other formative experiences can lead to a variety of motivations.

Some of us have a desire to rescue, we might be subject to countertransference, or we can collude. I have seen harm come to individuals on occasions, thankfully rare, where over-involved practitioners with poor boundaries conspire with their clients against the very services that are most likely to be able to help them.

When dealing with people, remember you are not dealing with creatures of logic, but with creatures of emotion, creatures bristling with prejudice, and motivated by pride and vanity.

Dale Carnegie

Some of us feel threatened when those who have depended on us for help want to become independent and move on. We may resist routes that can lead people to ‘abandon’ us. I have heard so much resistance to mutual aid, for instance, across my entire career in addictions – way beyond what is logical or reasonable – that it makes me wonder just what it is driving it. Could the lack of tolerance and acceptance be in part the fear of being divested of our charges, the pain of potential loss?

I’ve heard it said that without self-care we are prone to absorbing some of the disordered behaviours and thinking that can impair our clients – in a sense soaking up some of the pathology of addiction. Good supervision can increase insight and help to prevent this, but where supervision is not available or not utilised, disharmony and friction can develop and spread. Organisations and individuals who have a tendency to blanket-blame and shame others (others for the most part who are genuinely doing the best they can) may be suffering from this. Difficult people and difficult cultures exist, and we need to find ways to deal with them, exhausting though that may be.

Just because you’re dealing with difficult people, does not mean that you must become like them.

David Leddick

The work is challenging

Supporting people with substance use problems can be rewarding, but it can also be challenging. The high rates of death for those with alcohol and other drug problems are distressing. Disclosure of trauma and adverse childhood experiences can be difficult to hear and leave us lingering anxiety and disquiet. Sadness, anguish and grief can steal in and set up permanent home.

We can continue working but begin to detach or distance to the point where we become less empathic and compassionate. When we struggle like this, we may be less tolerant or even become cynical. Our relationships with others can then suffer and we take on a negative mantle but fail to recognise what’s happening. High sickness rates and excessive turnover in teams can be a reflection of this.

The way forward

And the solution to the bellicosity? You’ll need a smarter person than me to give a definitive answer to this.Addressing similar issues, Bill Stauffer quotes something that resonates with me ‘we no longer unite on things we agree on, we come together focused on things we hate’ – while this is not my whole experience, I am afraid that there is a kernel of truth here.

Love difficult people. You are one of them.

Bob Goff

A fundamental principle to moving forward is first taking a look at the part we play in this ourselves. What’s my thinking and behaviour like?.

We must examine our own flaws and blind spots in order to understand our common ground.

Bill Stauffer

Further, were we to focus on common ground, perhaps we could bring healing and consensus. On my best days I try to find that middle way, but as I say, I’m passionate too, my opinions are forged in a crucible of fire, I react to what I understand as others’ unreasonable positions, and I have my own blind spots. Sometimes I sit comfortably in my own echo chamber. There is a real risk that we lose sight of the people who we are trying to help as we pursue our own agendas.

The reason I’m mostly writing in first person plural (‘we’) is that I recognise many of these tendencies and vulnerabilities in myself. I get passionate, frustrated, angry and hurt, but when I take ownership of these reactions rather than blaming others, it gets easier for me to move forward. If I ever get good at this, I’ll let you know.

Show respect even to people that don’t deserve it; not as a reflection of their character, but as a reflection of yours.

Dave Willis