Addiction is normally framed as a chronically relapsing disorder, but a recent research paper from John Kelly and colleagues challenges us to think again. We actually don’t know as much as we might about recovery trajectories and, in terms of the number of attempts needed, there may be grounds for greater hope.

Previous research

Kelly and his colleagues point to groundwork done by other researchers which fits in with the chronic relapsing description. More than 50% of those starting addiction treatment in the USA do not complete it, 58% have had at least one previous treatment episode and more than 50% of those leaving treatment for alcohol or other drug problems relapse within 90 days.

Smoking cessation attempts have been much better studied – the number of quit attempts before successfully stopping long term is reported to be between 6 and 30 depending on the research method. Kelly and his colleagues point out that it would be good know the equivalent number of recovery attempts for alcohol and other drugs. If it takes 30 attempts to get into stable recovery, that could well act as a disincentive to trying.

Previous research has been limited because it’s pretty much focused on treatment populations. A 2005 study by Dennis and colleagues following up 1,200 patients going through publicly funded treatment found that for those achieving a year or more of abstinence, the median time from first use to last use was 27 years and from first treatment episode to last use was nine years. Feels a bit gloomy.

This research

Kelly and colleagues set out to pin down how many recovery attempts people have on average before successfully resolving an alcohol or other drug problem. They also wanted to identify the things that predicted the number of attempts and look at the relationship between the number of attempts and quality of life in recovery.

They identified 2000 people from a survey database who identified as having resolved an alcohol or other drug problem and asked them how many prior serious recovery attempts they had made. The answers were illuminating.

One of the main findings was how skewed the data were. Attempts could be as low as one or as high as one hundred. It looks like a relatively small group of people had very high numbers of attempts which means that the average number of attempts identified (5.35) is misleading. The median (bang in the middle) number was 2. The modal (most common) number of serious recovery attempts was 1.

There was no association between number of recovery attempts and age, sex, education, or household income. Those who had been diagnosed with depressive or anxiety disorders or who had received treatment or recovery support services including inpatient, outpatient mutual help, or any support service, reported a greater number of recovery attempts.

The researchers suggest that a higher number of recovery attempts needed before alcohol and other drug problems are resolved is ‘independently related to greater psychological distress, but not other indices (e.g., quality of life, happiness; self-esteem), regardless of how long one has been in recovery, prior service use, or the presence of other psychiatric comorbidity.’

The authors theorise that there could be a group of individuals who have ‘suffered from either a greater burden of or sensitivity to stress.’ This group could have found that recovery-related changes were more challenging or ‘perhaps represents those who have found a way to stay in recovery despite a greater burden of sensitivity to stress.’

For most people, the number of serious recovery attempts needed is actually quite low, but with certain subgroups (i.e., likely those with higher severity/ chronicity/comorbidity and lower recovery capital), requiring more attempts to achieve success. Yet, it is these more severe subgroups that are perceived as the norm, when the opposite is in fact true.

The authors point out some limitations in their methodology – the cross sectional nature, the reliance on self-reporting and the non-specific term ‘serious attempts’.

What does it mean?

It’s clear that those who identify as having resolved their problems with alcohol and other drugs are a diverse group – some not having to go to treatment or access mutual aid at all, some managing to resolve their problems with few attempts and some having to have multiple attempts.

Targeting our highest intensity interventions (e.g. structured psychological therapies or residential rehabilitation) to the most vulnerable may short circuit the number of attempts needed and help them achieve their goals faster. For this we need a staged series of treatment interventions that are highly individualised (as the authors point out) and that are joined up – a recovery-oriented system of care in other words. And resources to deliver this.

Here’s the authors’ hopeful bottom line:

The median number of recovery attempts, however, was surprisingly low and may offer hope to those struggling with alcohol and other drug problems.

How Many Recovery Attempts Does it Take to Successfully Resolve an Alcohol or Drug Problem? Estimates and Correlates From a National Study of Recovering U.S. Adults John F. Kelly, Martha Claire Greene, Brandon G. Bergman, William L. White, Bettina B. HoeppnerAlcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019 Jul; 43(7): 1533–1544. Published online 2019 May 15. doi: 10.1111/acer.14067

Photo credit: istockphoto.com/lovethewind (under licence)

Nick Goodwin was a Marine Corps Infantry Officer with an attitude of invincibility. Then he ran into a wall of self-doubt. One question kept coming up, morning after morning.

“On the one hand I’m telling myself I’m the strongest person alive—you’re a Marine Corps Infantry Officer, you’ve led 300 people—and then the other part of it is saying what the heck, why do I wake up in the morning convinced that I’m never going to drink again and by 7 p.m. I’m drinking again?!”

Nick decided that the reason was a combination of factors. Here’s the short version.

Nick joined the Marines two days after his high school graduation, then spent almost nine years staying in top shape, travelling throughout the Pacific theater, becoming an officer, and being responsible for hundreds of men and women serving their country. Important, high stakes stuff. He speaks of valuable lifetime experiences in the military, including the chance to see so many different countries and shape lives. Plus, some of the fun to be had by hanging out with Australian Commandos.

Near the end of his service, the last year or so, Nick started struggling with over-indulgence of alcohol. He now sees the slide as a reaction to his pending discharge. Nick knew, without a doubt, that life was going to change dramatically, and knowledge that revved up his anxiety, which led to more drinking, which caused its own anxiety. Around and around he went, like many others struggling with alcohol addiction. But in Nick’s case, the party was just getting darker.

Upon leaving the service, Nick’s marriage fell apart. Divorce is rarely easy, and in this case, it was quite harsh. All the issues of finance, custody, living arrangements, etc. packed a punch. What made it a knockout, Nick later reflected, was the complete loss of a goal orientation for his life, something he has always had in the military.

Nick was in trouble and he knew it. He tried AA and SMART, but didn’t stick with either. He kept drinking. The rest of the details don’t really matter. What matters is what happened next.

Isolated and disconnected from others during COVID, Nick turned to the Veteran’s Addiction Recovery Center and asked for help. He wanted inpatient treatment, believing it was the only way he would succeed in what had so far been a losing battle. The VA informed him that it was not an option but suggested he try SMART Recovery again, this time online. Nick dove in and found the tools and resources he needed. The best part is that they were right for him—a hard driving, goal oriented, cocky ex-Marine with a nagging sense of self-doubt. Nick explains the connection.

“I don’t like being told what to do, which is [what you get] in a lot of the programs I found. It’s kind of somewhat of a method they use. But SMART Recovery, they view it as a choice.”

Nick believes this focus on choice is consistent with addiction itself, in that his addiction was self-managed, so his recovery should be too. He also appreciates that meeting facilitators don’t control meetings. Instead, participants share ideas and experiences with one another and use SMART materials that are practical and science-based. Whatever the substance or activity that a person struggles with, Nick explains, changing negative thinking is one of the keys.

“When they talk about leading a balanced life, to me, if you do that, addiction becomes a kind of a symptom. It has been very effective in my life dealing with depression and anxiety…without this program I wouldn’t have cured those things.”

Nick decided that he wanted to use what he knew about his own recovery as a way of serving others, so he became a trained SMART facilitator. Naturally, he directed his attention toward what he knew best helping to guide and provide opportunities for veterans. With the help of another SMART facilitator who was also ex-military, a meeting for Veterans and First Responders was started. Bringing the circle around again, this time in a positive direction.

Today, the combination of positive self-talk and a renewed goal orientation has brought Nick to a good place. The kind of place that includes purpose.

“[SMART] not only keeps me sober but keeps me enjoying life. SMART Recovery, really helping people recover, is my purpose now.”

There is a strong ripple effect when a person embraces SMART Recovery. Nick relies on SMART’s tools for himself and has chosen to pay it forward by becoming a SMART facilitator and working with veterans and First Responders. This ripple is possible because mutual support group meetings and science-based materials are available to those who desire a self-empowered, stigma-free Life Beyond Addiction, where meaning, purpose, and positive growth are the norm.

Your year-end gift to SMART Recovery will be used to launch our important work in the best possible way. Our goal is to make 2021 a less isolated and difficult year for individuals and families that are battling addictions. SMART Recovery is poised to make a significant impact and help individuals live fulfilling and meaningful lives.

Additional resources:

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

What’s more harmful? Blame or pessimism?

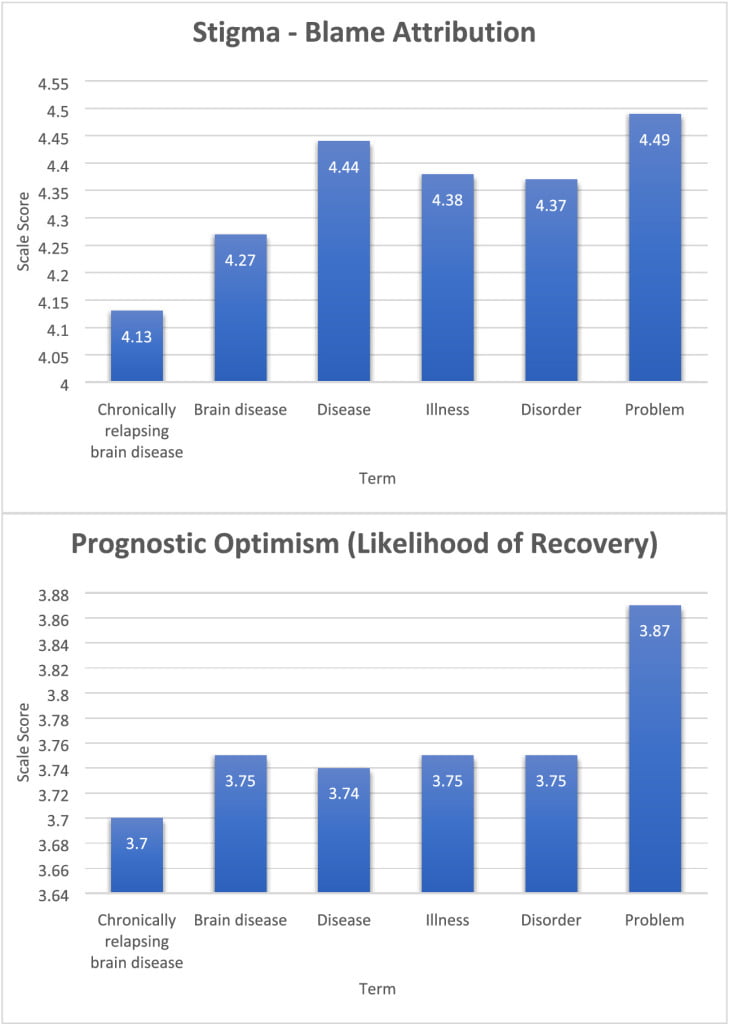

Kelly et al. find that ‘chronically relapsing brain disease‘ was associated less stigmatizing blame and more pessimism about their capacity to recover, while ‘problem‘ was associated with more stigmatizing blame and more optimism for their capacity to recover.

…exposure to the ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’ term was associated with the lowest levels of stigmatizing blame attributions; in fact, exposure to any other term was associated with a significant increase in stigmatizing blame although, intriguingly, the blame effect was related in a linear ordinal fashion with ‘problem’, resulting in the greatest stigmatizing blame attribution. In contrast, study participants who were exposed to the person described as having an opioid ‘problem’ compared to ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’ exhibited the strongest beliefs that the person could recover (Fig. 1), were less dangerous and less likely to require continuing care. These findings support the use of the ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’ term to reduce stigmatizing blame, but simultaneously suggest that this may not be the best term to use to convey the more positive notion that someone with opioid‐related impairment is approachable and can recover; in that case, the less medical and more generic, ‘problem’ term may be optimal.

Kelly, J. F., Greene, M. C., and Abry, A. (2020) A US national randomized study to guide how best to reduce stigma when describing drug‐related impairment in practice and policy. Addiction, https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15333.

It seems noteworthy that the currently favored term, disorder, didn’t fare well. For me, this illustrates the tail-chasing we inflict on ourselves when we let the attitudes of others determine what language is acceptable or unacceptable. We shouldn’t surprised that their attitudes are irrational and inconsistent. Can we yoke our language to their attitudes without tying ourselves in knots and surrendering a little of our agency? I’m skeptical.

We do this with hopes of benefits like greater acceptance and reduced stigma, and there’s reason to believe those benefits can be real in some situations.

Are there also consequences to this approach? I don’t know.

Could this attention to changing our language distract us from the real problem (other people’s attitudes and the real world manifestations of those attitudes)? Could it divide us because we start policing/managing each other in an attempt to reduce the negative attitudes of others? Could it create new stratifications within our communities?

Shawn Fisk is an addiction treatment counselor in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. His lived personal and professional experiences have led him to challenge cognitive discrepancies and chart a new path for his and his clients’ lives.

In this podcast, Shawn talks about:

- The privilege of working at Serenity House, an intensive, in-house men’s recovery home

- Giving the residents the opportunity to model and practice new skills to replace old behaviors

- His life as a competitive athlete and sports psychology coach

- Getting the opportunity to hit the reset button

- Taking Carl Young’s advice to find the courage to look at the dark things and find freedom

- Learning to value himself enough to take care of himself

- Applying SMART tools to behaviors like over-eating or spending

- Understanding labels

- Freedom from judgement

- His perspective on Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT)

- Helping people see their value

- Finding a new hobby every year

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

“The only way to support a revolution is to make your own” – Abbie Hoffman

The title of the post is a thinly veiled reference to the late social activist Abbie Hoffman. It has been said that the best way to get stuff done is to not have to take credit for it. The intent in posting this is to ask readers to review the ideas, take them to add to efforts to get ideas out there into the world for consideration in a spirit of contribution.

Readers may really like the ideas, readers may like some and not all, or some may not even like any of them. To all I say wonderful! Use what you like and dispense with the rest. Take in whole, modify, or even delete and move on. Feedback welcomed – I am genuinely interested in your thoughts.

So below and ATTACHED are ideas for improving our substance use care system. As Abbie said, start your own revolution, but perhaps we may all also listen to each other and seek the common ground that will benefit all of us and avoid the toxic ego centered debates that result in a quagmire of conflict that ultimately harms us all.

While largely mine in authorship, the ideas are the culmination of a whole lot of conversations with people here in PA and beyond and influenced by some of our community’s deepest thinkers.

Guiding Principles of Consideration on Treatment & Recovery for the Biden Administration

Scope of the Problem – Addiction and its consequences are arguable our greatest domestic challenges, costing lives, breaking up families with devastating community and economic consequences across our entire society.

- The COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating the dynamics of deaths of despair and will eventually eclipse it.

- Historically, our treatment & recovery has been acute focused and fragmented. Stigma against persons experiencing addiction has resulted in a care system built on low expectations of recovery. Even the concept of abstinence as defined as not use addictive drugs in ways not prescribed has been stigmatized by some.

- Despite the reality that 85% of persons who sustain recovery over five years remain in recovery for the rest of their lives, our care system is not designed around this overarching goal.

The Goal – Our entire social service and behavioral health system should be aligned towards a long-term recovery orientation to focus on restoring individuals, families and communities to full functioning and freedom from addiction.

Treatment and Recovery Support Services – Addiction is a bio-psycho-social-spiritual disorder impacting diverse communities. We need to equitably address all aspects of it and not solely focus on biological and medical dimensions.[1]

- We believe in and support the NIDA Principles of Effective Treatment[2]. Federal funding should follow these principles and guide who and what is funded in an equitable manner that meets actual needs.

- The five-year recovery model currently only used in professional monitoring programs, should be scaled and modified to be available to everyone with an addiction, to replicate these remarkable recovery rates for persons using MAT and non-MAT pathways in order to expand recovery opportunities for millions of Americans.[3]

- Care must address polysubstance use and not be single drug focused as this is how addiction occurs in real life.

- Study and implement Cascade of Care for OUD as a framework to bridge the divide between harm reduction, prevention, treatment, and recovery and effectively build out a comprehensive continuum of care for everyone.[4]

- Full implementation and enforcement of parity for addiction treatment with other chronic conditions is essential.

Many Paths to Recovery – Recovery is a voluntarily maintained lifestyle characterized by sobriety, personal health and citizenship[5].

- People should receive individualized care. No single pathway is best for everyone.

- There is robust evidence to support Twelve Step Facilitation[6] and federal funding should be available to programs that utilize this as their treatment modality as well as other effective strategies including and beyond medication.

- Recovery builds resiliency to overcome trauma and as a result, we get better than well7.

Recovery in Criminal Justice While we must work towards getting people help prior to involvement with the criminal justice system, we recognize that this doesn’t always happen. As a result, addiction care should be provided before, during and after involvement with the criminal justice system, including pre-arrest diversion programs.8 9

Education & Workforce – All helping professionals must receive mandatory education on addiction care and recovery.

- The addiction professional workforce has a special skill set that needs to be recognized as a specialty with compensation to match10

- National credentialing standards need to be created by and for the addiction professionals they will guide.

Research – Published research should consider “real world” conditions such as polysubstance use and longer-term outcome measures focused on the bio-psycho-social-spiritual aspects of addiction and recovery.

Payment Reform – We need to incentivize long-term recovery and move away from our historically acute, fragmented care that yields poor outcomes such as continuum of care models such as the Addiction Recovery Medical Home Alternative Payment Model (ARMH-APM)11

[1] https://www.asam.org/asam-criteria/about

[2] NIDA. 2020, September 18. Principles of Effective Treatment. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition/principles-effective-treatment on 2020, December 3

[3] Dupont, R. L., Compton, W. M., & McLellan, A. T. (2015). Five-year recovery: A new standard for assessing the effectiveness of substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 58, 1-5.

[4] https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/news-releases/2019/01/cascade-of-care-model-recommended-for-opioid-crisis

[5] Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel. What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007 Oct;33(3):221-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001. PMID: 17889294.

6 Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD012880Hibbert LJ,

7 Best DW. Assessing recovery and functioning in former problem drinkers at different stages of their recovery journeys. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011 Jan;30(1):12-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00190.x. PMID: 21219492.

8 Butzin CA, Martin SS, Inciardi JA. Evaluating component effects of a prison-based treatment continuum. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002 Mar;22(2):63-9. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00216-1. PMID: 11932131.

9 https://ptaccollaborative.org/about/

10 https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/substance-use-disorder-workforce-issue-brief

11 https://www.incentivizerecovery.org/

When the subject of residential treatment comes up in the addiction treatment field, there is a response I hear often (but not always). It’s a frustrating refrain. It goes like this: ‘there’s no evidence that rehab works.’

This view can and should be challenged, but what is true is that complex interventions like residential rehabilitation for drug and alcohol problems are difficult to study, say in comparison to a medication intervention. The evidence base needs to grow.

Commentators have been calling for more research for at least a decade and a half. While it’s fair to say we could do with knowing more about residential treatment, there is evidence around already. It could do with having a higher profile.

Effective Interventions

The Scottish Government have looked at this three times over the last sixteen or so years. Firstly, in 2004 the Effective Interventions Unit (EIU, now disbanded) published a paper reviewing detoxification and rehab services. Residential detoxification and rehabilitation services for drug users: A review.

The EIU found that the elements influencing effectiveness were – time in treatment, retention in treatment, client characteristics, and the provision of community aftercare. They said treatment should be at least three months long.

The authors made a recommendation: ‘Further research in this area may focus on undertaking a more detailed mapping of residential services in Scotland, improving retention rates and investigating models of good pathways of care between community and residential services.’ That mapping, it turns out, would be a long time coming.

Research for Recovery

In 2010, the Scottish Government published a paper ‘Research for Recovery’ which reviewed the evidence base. What did the researchers have to say?

‘Residential rehabilitation programmes are one of the longest established forms of treatment for drug addiction. Studies from the UK and the USA have shown improved outcomes after treatment in residential rehabilitation programmes. In DATOS, drug use outcomes after one year were good for clients who were treated in long-term residential and short-term inpatient treatment modalities in the USA.’

They also found that: ‘Regular cocaine use…was reduced to about one-third of intake levels among clients from both the long-term and short-term residential programmes, as was regular use of heroin.

In terms of opiates and harm reduction: ‘Rates of abstinence from illicit drugs have also been found to improve after residential treatment. In the UK, NTORS found that 51% of the drug misusers from residential rehabilitation programmes had been abstinent from heroin and other opiates throughout the three months prior to 2-year follow-up: rates of drug injection were also halved, and rates of needle sharing were reduced to less than a third of intake levels.’

Treatment in Scotland

In the Scottish treatment outcome study, DORIS, undertaken between 2001 and 2004, low rates of sustained abstinence were reported from stabilisation-focused community treatment. While abstinence is not necessarily the goal of medication assisted treatment, it is the goal of some seeking help for opiate problems.

What the DORIS researchers did find was that ‘residential rehabilitation treatment is more effective in promoting abstinence thirty-three months on [from the start of treatment] than other treatments outside prison. Ex-residential rehab clients were twice as likely as those who had undergone different treatments at baseline to be abstinent – apart from cannabis.’

Therapeutic communities

In our mapping of residential treatment services in Scotland, the majority of those responding reported using a therapeutic community model of treatment. A review of the published literature (from 2000) on therapeutic communities (TCs) in 2014 found: ‘TCs are generally effective as a treatment intervention, with reductions in substance-use and criminal activity, and increased improvement in mental health and social engagement evident in a number of studies reviewed.

The researchers also commented that the research ‘suggests individuals with severe substance-use disorders, mental health issues, forensic involvement and trauma histories, will benefit from TC treatment.’

2017 Review

Sheffield Hallam University published a review of Residential Treatment services in 2017. They found:

‘There is a strong and consistent evidence base supportive of the benefits of residential treatment that derives both from treatment outcome studies and randomised trials. Although more expensive, there is evidence that the initial costs of residential treatment are to a large extent offset by reductions in subsequent healthcare and criminal justice costs.

There is a clear dose effect for residential treatment with longer duration of treatment and treatment completion both strong predictors of better outcomes. A much stronger evidence base exists around attaining employment, stable housing, and ongoing support and aftercare as predictors of success.’

But treatment doesn’t stand alone:

‘There is a strong supportive evidence base around continuity of care, whether this takes the form of recovery housing or ongoing involvement in mutual aid groups.’

Their bottom line:

Overall, it is clear that an effective and recovery-oriented treatment system must include ready access to residential treatment for alcohol and drug users both to manage the needs of more complex populations and for those who are committed to an abstinence-based recovery journey

Residential Treatment Services Evidence Review 2017

2019 Review

A review of recent studies on residential treatment found that research was limited, but they did identify 23 studies of which 8 were rated as methodologically strong (including our study of a cohort of patients from Scotland). They found that the results of their research provided moderate quality evidence for the effectiveness of residential treatment in improving outcomes across a number of substance use and life domains.

They also said there is also some evidence that treatment may have a positive effect on social and offending outcomes, concluding with caution, that results suggest that best practice rehabilitation treatment integrates mental health treatment and provides continuity of care post-discharge.

2020 Working Group

Following in the footsteps of the 2004 EIU report on residential services and the 2020 review of the evidence for recovery, new work commissioned by the Scottish Government has just been completed. It was already clear that access to rehab was patchy and funding complex. The principle that residential rehab should be available to those Scots who need it was the starting point set by government. It may have taken 14 years for Scotland to answer that EIU call to map residential treatment services, but we’ve just done it and you can find a summary of what we found here. Our group also found evidence for the effectiveness of residential treatment.

Research please

As I’ve indicated, everybody who has looked at this has said the same thing – we need more research! Getting methodologically rigorous studies up and running to improve our knowledge is important. Indeed, the Residential Rehabilitation Working Group called for more research earlier this month in our recommendations.

In the service I work in, although we published one year outcomes, we now have data to five years after treatment in a cohort of patients we have been following up. Five years follow up in addiction treatment is not common!

It’s been a challenge to get resources to get the data published though I am hopeful this might change this coming year. We need long term outcome data particularly to evidence economic impacts and value for money.

Moving forward

Although we have questions about residential treatment that remain unanswered, there is already a body of evidence for its effectiveness and a commitment from the Scottish Government to make rehab more accessible. The recommendations of our group have been welcomed which is good news and we are currently developing a good practice guide. There are signs that more work may be commissioned.

Despite all I’ve written, it is important for us to remember that in terms of recovery journeys, rehab if accessed, will play a relatively small part. There is a lot of truth in the observation, that if recovery is the journey from Edinburgh to London on the train, detox is equivalent to calling the taxi and rehab is the taxi ride to the station. While there is much focus on the telephone call and that taxi journey, the largest part of recovery takes place in communities with support of mutual aid, families and community recovery resources.

That said, a significant number of people in Scotland in recovery today will acknowledge the key role rehab has played in their journey and will support efforts to make it more accessible – not in opposition to other interventions, but as well as other interventions.

I hope in 2021 that there will be more of an appetite to explore what part residential treatment should play in Scotland and that the response, ‘there’s no evidence that it works’ will be heard less and less – because it is simply not true.

Photo credit: allesandrobiascioli/istockphoto.com (under license)

This week in Scotland we’ve been reeling from the impact of the publication of the 2019 drug-related death statistics. The awful graphs are everywhere, their bright colours standing in sharp contrast to the horror they relate. Our feelings clamour for attention, a powerful mixture of anger, grief, bewilderment and shame.

The newspapers are full of reaction to the statistics; front page bold headlines shout in outrage, editorials call for action. The stories lead on TV news broadcasts. Every morning and evening this week on my commute I’ve listened to radio broadcasters on BBC Scotland debate the issues and heard people, some of whom I know – experts and those with lived experience – interviewed for their reactions. Conversations with colleagues are dominated by the subject.

It’s been an affecting experience, but it’s reminiscent of something – something that disturbs me. It’s reminiscent of the reaction to last year’s drug death statistics publication. The worry I have is that after a fortnight of clamour, the dust settles, the feelings are emolliated, and other issues take the lead in the newspapers and on the TV. Then, if nothing changes, we go through the Groundhog Day again in the autumn of 2021. That would be heart-breaking.

Something changing?

Despite these fears, there are grounds to be a bit more optimistic. I do think the response this year is different. There is an urgency, a collective outrage, a widespread determination to make things different. There is an edge to this that is making us put our shoulders back, grit our teeth and hold our heads determinedly high in spite of the shame.

Journalists, broadcasters and national bodies have given a voice to those not normally heard – the families of victims, those suffering from addiction and those in recovery. This has happened to some extent before, but this year the voices are louder, clearer, more stirring. Out of this I can see a resolve developing that is different to what’s gone before. It’s encouraging.

There’s more though: a potential gamechanger – something I don’t think we’ve seen or heard before. Our First Minister (FM), Nicola Sturgeon, has said with frankness that what’s happening is ‘indefensible’ and that she would take criticism ‘squarely on the chin’.

Every person who dies an avoidable death because of drug abuse has been let down.

Nicola Sturgeon

She also said

We have much to do to sort this out – and sorting it out is our responsibility.

Alan Massie, commenting in the Times, describes this response as ‘unprecedented’ and ‘unusually candid’.

Action

Ms Sturgeon is going to attend the next meeting of the Drugs Deaths Task Force and will report back to parliament by the end of January. When pressed in parliament about poor rehab access, she said she was ‘not satisfied” that the number of rehab beds available was “necessarily sufficient or that they are being used sufficiently”. I hope she’s saying that because she’s been briefed on the Residential Rehabilitation Working Group’s report, published a couple of weeks ago.

Scotland’s had a historical blind spot with regard to residential rehabilitation, but here’s further evidence that things are changing. The Residential Rehabilitation Working Group was set up by Public Health Minister, Joe Fitzpatrick at the end of the summer this year. We were told to start from the underlying principle that everyone who needs rehab should have access to it – a clear commitment to improving things.

The rehab group was allowed to be independent and experienced no interference or even influence by government. Our recommendations were entirely our own and the report was published in full. These recommendations have been welcomed and some resource already allocated to take them forward. Rehab is not the solution to drug-related deaths, but it will have a part to play.

Shared responsibility

While Nicola Sturgeon has taken responsibility for our drug deaths crisis, I don’t think the responsibility is hers alone to shoulder. We all have a part to play. The causes of drug (and alcohol) related deaths are complex and manifold. The solutions need to be diverse.

Harm reduction interventions need to be widely available, accessible, delivered efficiently and proactively and evaluated and improved. Harm reduction services also need to have porous borders with treatment and recovery services and have hope embedded in the form of peers in recovery working within teams. A recovery-oriented system of care sees interventions not in silos, but in a continuum with the individual’s needs at the centre and the person on a journey. The person’s goals, not the professional’s goals (which can be at odds) should be paramount.

Treatment needs to be a full menu of evidence-based, joined-up interventions, accessible when needed, which is funded according to the need of the nation. If we have more than three times the drug death rate of England, the first step needs to be to increase the resource to meet our need. When the last round of cuts came, in my service we were asked to work harder with less resource, which we did for the sake of our patients, but we need so much more than the expectation of workers knuckling down with goodwill.

Research

The part that communities of recovery and those with lived experience can play in alleviating the crisis needs to be better recognised. So much of our research is focussed on the problem and interventions to try to ameliorate the problem. I have no beef about the importance of that. But are we missing a trick?

We have thousands of people in Scotland in long term recovery from substance use disorders. What worked for them? What barriers did they face? Why did they not die from addiction? Why don’t we know the answers to these questions? Those answers will help us. Perhaps some resource needs to be focussed on solutions already experienced. Perhaps then the solutions will grow for others.

Hope instead of despair

Finally, I think that we as citizens and communities need to take responsibility too. It’s our nation’s problem. The risk factors for addiction – trauma, stigma, poverty, lack of opportunity, intergenerational substance dependence, lack of hope etc. – these are not just the responsibility of government. Each of us who feels sorrow and shame over the current emergency can play a part in addressing these. Many already are.

The best way to not feel hopeless is to get up and do something. Don’t wait for good things to happen to you. If you go out and make some good things happen, you will fill the world with hope, you will fill yourself with hope

Barack Obama

Photo credit: istockphoto.com/ZargonDesign (under license)

December 17th, 2020

He who shows himself at every place will someday look for a place to hide. –African Proverb

Earlier blogs in this series explored the benefits and limitations of public recovery disclosure, the potential risks to multiple parties involved in such disclosure, and the ethics of recovery disclosure. In this final blog in the series, we explore guidelines for individuals and organizations aimed at minimizing risks related to public recovery disclosure.

The Decision to Disclose

Before disclosing our recovery status or details of our addiction/recovery experiences at a public level, we suggest giving careful thought to such questions as:

- Is this the right time in my recovery to share my recovery story at a public level? Will this strengthen my recovery or would it be a diversion from more critically needed recovery activities?

- Are there any negative effects for myself, my family, my community, and organizations within whom I am associated that could result from sharing my story in public or professional settings?

- Could such story sharing subject me to discrimination in housing, education, employment, health care, or social and business opportunities? Could it have any legal ramifications?

- Do I have a support system that could help me manage any such effects if they should arise?

- Will I be sharing my story alone or alongside other people in recovery?

- Do the potential benefits of public disclosure as a community service outweigh the potential personal risks?

- Who is controlling how my disclosure will be used and is there an explicit right for me to have the final edit on what elements of my disclosure are presented?

Purpose of Public Disclosure

Many people in recovery will have shared their recovery story with family and friends, with medical and treatment professionals, and with other people in recovery before the opportunity for public recovery disclosure arises. Public disclosure is different from any of these preceding situations and involves a different purpose and style of storytelling.

Public recovery storytelling is about service to a larger cause than self. It is the use of self and one’s own story as a catalyst for personal and social change. With each story sharing opportunity, we prepare ourselves by asking key questions. What do I want members of this audience to understand, feel, and do? How can I present my story in a way that will achieve those goals? How can what I do today contribute to the larger goals of the recovery advocacy movement?

It is important that addiction treatment and recovery community organizations provide a process of informed consent when inviting individuals to share their stories in public and professional contexts. This involves a clear statement of the potential benefits and risks of public disclosure and screening out individuals for whom such disclosures present an unacceptable level of risk. Asking individuals currently receiving services to participate in public story sharing or marketing activities is coercive and exploitive.

Disclosure Preparation

Many of the risks involved in public recovery story sharing can be avoided with adequate orientation and training. Messaging training has been an effective tool used by Faces and Voices of Recovery and other recovery advocacy organizations to prepare people for this unique service ministry. Messaging training spans both the intent and content of public story sharing and the mechanics of effective story sharing (e.g., language, tone, adaptation for different cultural contexts and audiences, etc.). Pursuing these activities within an established recovery community organization helps assure peer and supervisory support for the “ups and downs” of such sharing experiences.

Public Self-disclosure and 12-Step Anonymity

AA, the precursor of all 12-Step programs, promulgated a tradition of personal anonymity at the level of press as both a protective device for AA and as a spiritual principle. Public disclosure of recovery status and sharing one’s recovery story without reference to affiliation with a particular 12-Step program complies with the letter of 12-Step traditions (See Advocacy with Anonymity), but it may not always meet the spirit of the Traditions. This could occur when advocacy is used as a stage for assertion of self (flowing from ego / narcissism / pride and the desire for personal recognition) rather than as a platform for acts of service flowing from remorse, gratitude, humility, and a commitment to service. For members of 12-Step fellowships, adhering to anonymity traditions (in letter AND spirit) in public recovery story sharing is recommended as a protection both for 12-Step programs and for the protection of the recovery advocate.

Timing of Disclosure

Our capacities (energy, abilities, competing needs and demands) for recovery advocacy ebb and flow over time. It is appropriate to ask ourselves if this is the optimal time for public recovery story sharing, whether this is the first time we have such opportunity or whether we need to take a break from such activities during times of personal distress or competing demands that require our focused attention. Warning signs indicating the latter include losing emotional control over the content of our story sharing (via unplanned expressions of frustration, resentment, anger, sorrow) or experiencing boredom or a loss of energy in our public story sharing. Difficult experiences and emotions can be referenced strategically within our talks (once we have emotional control over them), but public and professional meetings are not the appropriate venues to work out unresolved traumas of the past or present. When we drift across that line, it is time to take a break from this public service role.

Scope and Focus of Disclosure

People in addiction recovery have many stories they can share. There is the life preceding the onset of drug use, one’s addiction career, the turning point of recovery initiation, and the story of one’s personal and family life in and beyond recovery. All of these may be touched on in public recovery story sharing, but the emphasis of this story must be on the recovery story and the lessons drawn from it. Great care is required with the media to maintain this focus. There are dangers that others hijack a recovery story intended to lower stigma in a way that fuels stigma, social marginalization, and the criminalization of addiction. We best serve the advocacy movement and protect ourselves by maintaining a focus on the recovery side of our stories and how we escaped the chaos and drama of addiction.

Depth of Disclosure

There exists a continuum of intimacy defining the degree of risk in public recovery story sharing. There are experiences, feelings, and thoughts known only to ourselves that we have not shared with anyone else. There are experiences, feelings, and thoughts we have shared with only within our most trusted relationships. There are the communications we have expressed only within the context of professional counseling, within a sponsorship relationship, or recovery mutual aid meetings. And there are things about ourselves we have shared widely with those we encounter in our daily lives. Such communications range from high emotional risk to low emotional risk. The question is: Where does sharing our recovery story in professional or public meetings, in media interviews, or on social media fit in this continuum?

All recovery story sharing at a public level involves potential risks to ourselves and other parties, but those risks increase in tandem with the level of detail about our experiences contained within those stories. The category “people in recovery” includes highly armored people who are unable to trust others enough to share their real experiences, feelings, and thoughts. Others in this category enter recovery with no armor and no boundaries to facilitate the nuances of self-disclosure and self-protection in different settings and relationships. People existing on the extremes of this continuum from overly guarded to completely unguarded may need greater time in recovery prior to recovery story sharing at a public level. All people on this continuum need guidance and discipline to manage the depth of public recovery disclosure and the discipline to maintain this boundary over time.

Training and supervision related to public recovery disclosure can provide a safe setting in which we can address such questions as the following:

What is the level of risks (who could experience harm and to what degree?) in the following story sharing venues: a social media post; a radio, television or newspaper interview; speaking at a recovery celebration event; speaking to a professional audience; or speaking to a public audience; writing an article or memoir about our recovery experience?

What parts of my story are not appropriate to share publicly? (We want to break no-talk rules related to addiction/recovery, but we want to avoid disclosures that are so intimate in detail that they pose threats to our own emotional health or repel those who hear our story.)

What aspects of my past or present experience remain too emotionally intense to include in my public recovery story? (These are the boundaries we need to define BEFORE we stand before an audience or sit for an interview! Message training and peer supervision can assist this process.)

Have I avoided referencing other people’s stories who might experience harm or discomfort resulting from my disclosure? (It is best to get permission for inclusion of others within our stories, e.g., spouse, family members.)

Have I fully explored why I am sharing my story and sought feedback from other people who know me to understand the nuances and potential unintended consequences of disclosure?

Facing Criticism of Public Disclosure

As a final note, it is not unusual for individuals disclosing their recovery story at a public level to draw criticism for such activities from expected and unexpected quarters. You may be accused of “grandstanding,” “ripping off the program,” violating program traditions,” or be caught in the crossfires of various ideological debates. Some will comment on what you should have or shouldn’t have included in what you shared. Our advice is to have one or more people you are close to who can help you sort such feedback. And to positively use what you can and disregard the rest. Do know that such criticism is inevitable and can help us refine our message and its delivery—even when the criticism is unfounded and prompted by spurious motives.

Closing

We have tried in this series of blogs to explore the purpose, contexts, and risks of sharing our recovery stories at a public level and to explore some of the ethical issues involved in recovery story sharing. It is our hope that these discussions and suggested guidelines will serve as a catalyst for discussion and a tool for the training of recovery advocates who choose to join the vanguard of people who are putting a face and voice to the recovery experience.

Our stories have the power to achieve many things, but we must not embrace total responsibility for eliminating addiction/recovery-related stigma. Those individuals and institutions who spawned and perpetuated stigma and discrimination bear that responsibility. What we can do is offer our stories and our larger advocacy activities to offer hope to wounded individuals, families, and communities and do so in a way that protects our own health and safety.

Link to Blog Post HERE

Event Description

Committee Meeting for Olmstead Planning

Microsoft Teams meeting

Join on your computer or mobile app

Click here to join the meeting

Learn More | Meeting options

Event Description

Committee Meeting for Olmstead Planning

Microsoft Teams meeting

Join on your computer or mobile app

Click here to join the meeting

Learn More | Meeting options