Event Description

Committee Meeting

Online Access: Join ZoomGov Meeting

https://www.zoomgov.com/j/1605701173?pwd=TDcwRkQxSWliWXNUa3FvbU9wUjV0Zz09

Meeting ID: 160 570 1173

Passcode: Housing

One tap mobile

+16692545252,,1605701173#,,,,,,0#,,3532816# US (San Jose)

+16468287666,,1605701173#,,,,,,0#,,3532816# US (New York)

Dial by your location

+1 669 254 5252 US (San Jose)

+1 646 828 7666 US (New York)

Meeting ID: 160 570 1173

Passcode: 3532816

Find your local number: https://www.zoomgov.com/u/aebbl4aGYl

Event Description

The OPSA QA/QoL Subcommittee will continue the discussion of person-centeredness during this hour, with special emphasis on implications for quality assurance and quality of life frameworks.

When and Where: Tuesday, December 8, 2020 @ 12 – 1pm

Online Access: ZoomGov Meeting

Join Zoom Meeting: https://zoom.us/j/96940726234?pwd=UTRvYkhubVdrbGJwaXQwdGNaQVFIZz09

Meeting ID: 969 4072 6234

Passcode: 601878

One tap mobile

+19294362866,,96940726234#,,,,,,0#,,601878# US (New York)

+13017158592,,96940726234#,,,,,,0#,,601878# US (Washington D.C)

Dial by your location

+1 929 436 2866 US (New York)

+1 301 715 8592 US (Washington D.C)

+1 312 626 6799 US (Chicago)

+1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose)

+1 253 215 8782 US (Tacoma)

+1 346 248 7799 US (Houston)

Meeting ID: 969 4072 6234

Passcode: 601878

Find your local number: https://zoom.us/u/abIJpdPWu

Event Description

OPSA Special Presentation with Guest Speaker Leigh Ann Kingsbury on Person-Centeredness

The Office of the Senior Director on the ADA, home to the NC Department of Health and Human Services’ Olmstead Plan Development Initiative, is pleased to present an OPSA Holiday Special, Person-Centeredness: The Foundation and Firmament of Olmstead Plan Development and Implementation. Co-hosted by OPSA’s Committee on Quality Assurance and Quality of Life (QA/QOL), the December 8, 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM EST online event features Leigh Ann Kingsbury, MPA. Leigh Ann is a Managing Consultant for The Lewin Group where, among many other roles, she has served as the Lead for Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) and Care for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) Cross-Model Learning Network (CMLN). Previously, as Senior Associate Consultant for Support Development Associates, LLC, she served as a national consultant for behavioral health, intellectual/developmental disability (IDD), substance use disorder, and long-term care services organizations and state systems. Her work has long focused on the implementation of quality management and person-centered and recovery-focused practices, including the proprietary process, “Building a Person-Centered Organization and System.”

Leigh Ann’s 25-year career bridges the diverse service sectors. Her portfolio includes many years of planning and implementing services with and for, people with IDD; physical disabilities; behavioral health diagnoses and disabilities; older adults and families; and others with complex health needs, including people with dementia, rare diagnoses, acquired disability, and those at the end of life. Leigh Ann has also assisted hundreds of people with disabilities and/or older adults transitioning from institutional and congregate settings to community-based services, highlighting people’s gifts, talents, interests, abilities and needs, and implementing clinical supports, follow through and oversight. Her training in gerontology gives her significant expertise in developing services and supports for people with disabilities who have critical, chronic and/or life-ending illnesses. She is a Board Member Emeritus of The International Learning Community for Person-Centered Practices and the author of the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities’ People Planning Ahead: A Guide to Communicating Healthcare and End of Life Wishes.

When and Where: Tuesday, December 8, 2020 @ 11am – 12pm

Online Access: ZoomGov Meeting

Join Zoom Meeting: https://zoom.us/j/96940726234?pwd=UTRvYkhubVdrbGJwaXQwdGNaQVFIZz09

Meeting ID: 969 4072 6234

Passcode: 601878

One tap mobile

+19294362866,,96940726234#,,,,,,0#,,601878# US (New York)

+13017158592,,96940726234#,,,,,,0#,,601878# US (Washington D.C)

Dial by your location

+1 929 436 2866 US (New York)

+1 301 715 8592 US (Washington D.C)

+1 312 626 6799 US (Chicago)

+1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose)

+1 253 215 8782 US (Tacoma)

+1 346 248 7799 US (Houston)

Meeting ID: 969 4072 6234

Passcode: 601878

Find your local number: https://zoom.us/u/abIJpdPWu

Event Description

Committee Meeting – Marti Knisley will speak during the meeting about integrated community housing definitions, strengths/gaps of NC’s housing continuum, and experience of other states.

Online Access: Join ZoomGov Meeting

https://www.zoomgov.com/j/1605701173?pwd=TDcwRkQxSWliWXNUa3FvbU9wUjV0Zz09

Meeting ID: 160 570 1173

Passcode: Housing

One tap mobile

+16692545252,,1605701173#,,,,,,0#,,3532816# US (San Jose)

+16468287666,,1605701173#,,,,,,0#,,3532816# US (New York)

Dial by your location

+1 669 254 5252 US (San Jose)

+1 646 828 7666 US (New York)

Meeting ID: 160 570 1173

Passcode: 3532816

Find your local number: https://www.zoomgov.com/u/aebbl4aGYl

There are 200 deaths a day related to the opiate crisis in the USA. In Scotland we have the highest number of drug-related deaths in Europe, perhaps in the world. A task force set up by the Scottish Government has recommended six interventions to tackle our crisis which we hope will make a difference. I am increasingly convinced though that something is missing – something which could make a significant impact.

Getting plugged in

The concept I’m contemplating is simple and it’s not my idea by any means. It’s this: healthy social networks (the people we connect with) are protective. Improving them brings gains in physical and mental health. People suffering with addiction frequently have damaged or unhealthy social networks. They are often dislocated and estranged or excluded from being active community members. As I say, there is existing evidence on this, though there are serious questions about how far it has penetrated into the practice of treatment providers or commissioners.

If we look at existing research, there’s no better place to start than examining the impact of social networks on longevity and wellbeing. In 2010, Julianne Holt-Lunstad and her colleagues undertook an impressive meta-analysis (massive review of the evidence available) to see how social relationships influenced mortality. They found a protective effect for those with stronger social relationships. In fact, for this group there was a 50% increased likelihood of survival. In medical terms, this is a very large effect – similar to stopping smoking. You want to live longer? Get lots of friends.

Mark Litt and his colleagues explored this concept in alcohol-dependent men and women in 2009. In a high-quality trial, they tested out linking individuals into new pro-abstinence networks vs. other established treatments and found that those who formed new connections (in mutual aid) did better than established treatments. A stunning finding was that:

the addition of just one abstinent person to a social network increased the probability of abstinence for the next year by 27%.

Litt found that drinkers’ social networks can be changed by a treatment that is specifically designed to do so, and that these changes contribute to improved drinking outcomes.

So how are we doing on this front?

If we could get this sort of impact from medication in alcohol treatment settings, we’d be very happy, and if you are like me, you’ll be thinking, ‘lets go for it!’ Yet when commissioners asked 250 addiction treatment service users in Edinburgh in 2010 how many of them had ever been to a mutual aid group, the answer was less than 1%.

This is pretty dismal. In 2010, we weren’t doing very well in the city of Edinburgh. My hope is that if this was repeated today, we’d see an improvement. But would it be enough?

Getting equipped for recovery

The two papers that caught my eye this week which are relevant to this topic are worth a read. I’m not going to analyse them here, but I will pick out some key points. In the first ‘Are members of mutual aid groups better equipped for addiction recovery?’, Thomas Martinelli and colleagues interviewed 367 people in recovery from drug addiction and looked at how membership of mutual aid groups related to things like social networks, recovery capital and commitment to sobriety.

They recruited the participants in Belgium, the Netherlands and the UK by a variety of methods including social media, newsletters, conferences, posters, flyers, magazines and by contacting prevention and treatment organisations. Participants self-identified as being in recovery for at least three months and completed a questionnaire.

Findings

Interestingly, 69% reported membership of mutual aid groups at some point. When lifetime mutual aid members were compared with non-mutual aid members, some differences appeared with significant benefits to the mutual aid group members. These were identified in things like: paid employment (64% vs. 45%); abstinence from drugs (94% vs. 75%) and abstinence from alcohol (81% vs. 52%).

For those who were using drugs or alcohol, using days and drinking days were 3 times higher in the non-mutual aid group. There were strong associations with improved social networks, increased recovery capital (and ability to sustain recovery) and commitment to recovery for mutual aid group members. Those who were current members of mutual aid groups consistently reported more resources than those who had been members in the past. The benefits were greatest for members of 12-step groups, but positive outcomes did extend to non 12-step groups too.

Bottom line?

the expanding evidence on the benefits of mutual aid group participation should justify further exploration of its inclusion into system-wide practice of addiction services and to encourage services to refer to mutual aid groups

Getting a dose of recovery

In the other paper which focuses on the negative issues associated with social networks – ‘Social network theory—an underutilized opportunity to align innovative methods with the demands of the opioid epidemic’, Christina Cutter and colleagues point out that demand for opioid use arising from social networks and environment is an important contributing factor to the current opioid crisis.

Previous research on behaviours shows cluster effects (e.g. around obesity, suggesting that if you want to lose weight, you should hang around with thin friends). They recommend that we explore the ‘social contagion model’, an approach which puts forward that behaviours develop through role modelling and spread as if they are infective.

Their argument focusses on the problem (how opiate addiction spreads) and they express how understanding and exploration of this could help develop new strategies. They powerfully describe the issue of ‘social networks of despair’ arising from overdoses and deaths, but they also shine a light, turning things around and presenting the opportunity for the social contagion model to operate as a catalyst for recovery. I often paraphrase this as ‘if you hang around people in recovery long enough, you are likely to catch a dose of it.’

Indeed, the authors give mutual aid (AA) as an example of how this is done. After all, AA has now been shown to be as effective, if not more effective, than other evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Fittingly for these times, Cutter et al extend the contagion model and highlight the process for a cure:

the expanding evidence on the benefits of mutual aid group participation should justify further exploration of its inclusion into system-wide practice of addiction services and to encourage services to refer to mutual aid groups

The recent announcement of a vaccine against covid-19 has generated phenomenal interest and jubilation. Hope now flows where hopelessness lingered. Perhaps, as with covid-19, we need more than one vaccine against drug and alcohol problems to be researched, but hang on a minute! A cheap, tested, evidence-based vaccine already exists – assertively connecting people to mutual aid! This would appear to have a very significant impact on outcomes compared to most interventions.

Now, I’m not claiming this approach as an answer to our opiate (and alcohol) deaths. There is no single answer. What I am saying is that we ought to vigorously test out the social contagion/social networking model as part of the range of interventions we are currently adopting – the evidence is already strong and accumulating.

I’d like to see this approach at the heart of all of our interventions and have services held to account on how effectively they link service users into new social networks. Then I think we would really see change.

The is a post was initially published in 2018. Please note that abstinence can mean abstinence from illicit drugs, or abstinence from all drugs that produce euphoria or are commonly misused (including agonist medications, benzodiazepines, etc.). For the purposes of this post, this distinction is irrelevant because the arguments in the second article really apply to either definition of abstinence.

I was perusing past year articles in Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly and came across these two:

Achieving a 15% relapse rate

Article one, as the title suggests, examines Collegiate Recovery Programs (CRPs) and Physician Health Programs (PHPs), their outstanding outcomes, their common elements, and discusses their potential for application to other populations. The abstract introduces them this way [Emphasis mine. The reason will be obvious later.]:

The CRP and PHP models involve long-term, comprehensive components of care and ancillary services oriented toward highly transformative abstinence-based recovery.

The text of the article adds this:

Both models hold the maintenance of long-term abstinence as the general outcome of choice.

The closing discussion opens this way:

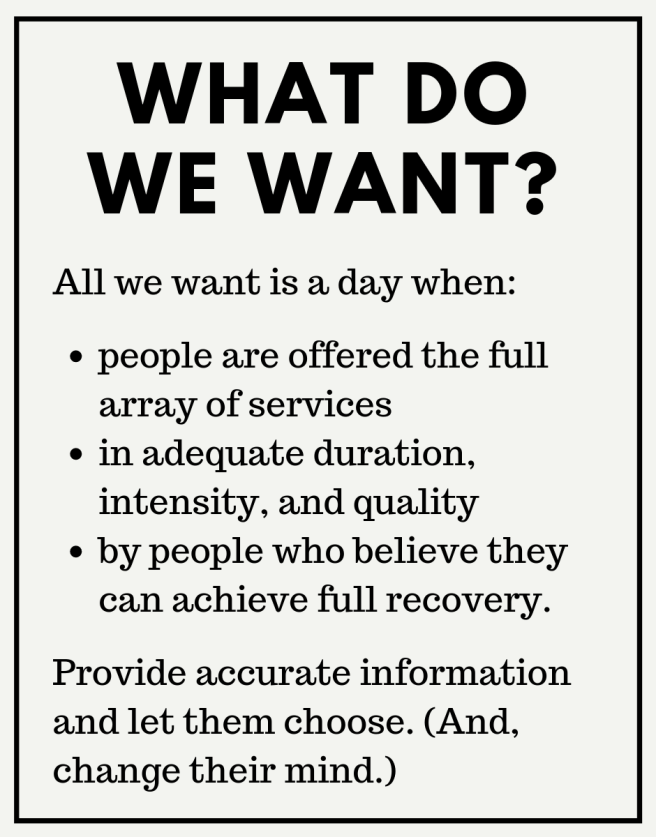

Is a 15% relapse rate attainable? Evidence would suggest that common factors among pockets of highly successful recovery may hold the ingredients needed to ensure low relapse rates for all addiction treatment. CRPs in particular provide an example of recovery supports that facilitate long-term recovery through addressing recovery and quality of life concerns concurrently, while the individual works to achieve greater social capital through education.

Expanding services and support to include broader depth and coverage of socioeconomic, ethnic, and other disparities that exist in the current system is of paramount importance if we are to see real societal change and test the efficacy of the PHP and CRP models. PHP clients, consisting of licensed professionals, obviously garner esteem, social credibility, and seem “worthy” of saving from addiction. In the same way, so do young people who have the wherewithal to engage in treatment and be successful in higher education.

“Motivational Interviewing cannot be used in its fidelity in abstinence-based treatment”

Article two makes the following argument:

A major underpinning of motivation interviewing is to “meet clients where they are at,” and tailor interventions to their specific stage of change. In abstinence-based programs, however, clients are immediately placed in the action stage of change, even skipping the preparation stage of change that is essential to maintain recovery. Furthermore, this choice is made for them, not only evidencing the inability to do MI, but also the lack of individualized treatment. Despite this disconnect, the abstinence-only approach is still used in many treatment facilities in the United States, with 72% of facilities providing 12 Step-based programs (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2017), which are abstinence based and noted as what someone must achieve it to attain recovery, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; 2016). It is important to highlight, however, that our position is not that 12-Step programs are not useful or ineffective. Conversely, 12-Step programs have withstood the test of time and are a valuable resource for many. What we are suggesting is that 12-Step programs are not for every client and, therefore, should not be the core of treatment programming. Rather, we propose individualized treatment consistent with the underpinnings of MI, which includes assessments, treatment planning, and counseling sessions based on harm reduction, not abstinence. Although abstinence is an excellent goal for recovery, the culture of a treatment agency cannot determine the goals for clients, which obviously is the opposite of individualized treatment. The clients themselves must determine their own treatment goals. MI continues to gain popularity and was reportedly being used in 90% of treatment programs (SAMHSA, 2017). Based on these findings, it seems that many facilities are employing an abstinence-based philosophy while also attempting to use MI. The following sections discuss how MI cannot be used in its fidelity in abstinence- based programs, despite many claiming to do so.

I’d argue that the framing here leaves a lot to be desired.

First, they cite that 90% percent of programs report using MI, but argue that most cannot be implementing MI with fidelity to MI principles because 72% report “providing 12 step-based programs.” IF these are incompatible, who’s to say that the infidelity is on the MI side? Couldn’t it be on either side?

Second, it’s worth noting that the SAMHSA report does not report on programs “providing 12 step-based programs.” Rather, the report tells us how many programs report using “12 step facilitation” (TSF). That distinction is important. The difference between a program that reports “providing 12 step-based programs” and one whose toolbox includes TSF is significant. The former implies that the 12 steps are the foundation for the entire program and are used with 100% of patients. The latter implies that TSF may (or, may not) be used with patients. In fact, the report indicates that 47% of programs report using TSF “always or often.” The survey provides no definition or guidance for “often”, leaving it pretty subjective.

Why would the authors characterize the data in this way? IDK

Further, earlier in the article they present the Minnesota model as representative of contemporary treatment services. However, the same report indicates that residential/inpatient treatment represented only 9% of all admissions in the report, and who knows what portion of that 9% received services resembling the Minnesota model? Another confusing, rather than clarifying, representation.

Treatment goals

So, article two appears to say that services with a goal of abstinence cannot be faithful to MI.

Is abstinence an appropriate goal in treatment? And, how should providers determine what goal(s) they want to organize their programs around?

A lot of this comes down to the nature of the problem you are treating, whether the problem is a behavior or a disease.

If we’re treating addiction (whose hallmark is impaired control), then abstinence is the goal that’s going to provide quality of life. AND, as the first article demonstrates, we have approaches that can deliver high rates of success.

If you’re addressing a lower severity problem, harm reduction or moderation are often good endpoints to focus on. These kinds of users can probably reduce harm and maintain a good quality of life.

Imagine we were discussing some other illness with severe physical, psychological, social, familial, occupational, and spiritual consequences. Further, imagine there are treatments what deliver relapse rates as low as 15%. Imagine there are barriers to engagement and retention in these treatments, and you wanted to use MI to improve engagement. Would it be inappropriate to have services organized around the goal of engaging and supporting patients in these effective treatments?

Which goals should take priority? Engagement rates in these successful treatments, or fidelity to the MI model?

What would we think about a cancer treatment program that takes no position on treatment options, and prioritizes symptom reduction and patient choice over remission?

To me, the authors of the MI article seem to be focused on AOD use as a behavior rather than a symptom of a disease.

It’s possible that they are focused on lower severity SUDs, or they don’t believe addiction is a disease, or they don’t believe there are meaningful differences in good care for addiction and lower severity SUDs.

It’s worth noting that the word “disease” appears only once in the article, and only when describing the Minnesota model.

I have no quarrel with their high-fidelity version MI model for lower severity SUDs, and I have no problem with it as a model to engage high severity SUDs (addiction) into other effective treatment models. (See posts about gradualism and recovery-oriented harm reduction.)

What are we treating? What are we seeking recovery from?

I imagine, maybe incorrectly, that the authors and I disagree on addiction as a disease.

I believe that addiction is a brain disease, and I like the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s definition:

Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors.

Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death.

Within the field, however, there once again seem to be growing doubts about addiction as a disease.

Some see it as an outdated metaphor or useful fiction, while others see it as an artifact of stigma, and others see it as a social ill. (It’s paywalled, but the NEJM just published an argument that addiction is a learning disorder and not a disease.)

Many of these models of understanding started outside of the field, but are being brought into the field, knowingly or unknowingly, by new professionals and advocates.

The problem is made worse by the DSM 5’s movement toward a continuum model which puts all AOD problems on one continuum/category. No longer are low severity problems and high severity problems categorized as different kinds of problems. Rather, they are now one kind of problem with different severities.

Fuzzy thinking?

I’m not an expert in MI, but I’m not sure I buy the argument that fidelity to MI demands that practitioners and programs be agnostic on abstinence as the ideal outcome for addiction. And, if it does, I wouldn’t want my loved one in a program that is neutral on the outcome associated with the highest quality of life.

So . . . what’s going on then?

Dirk Hanson offered a helpful observation a few years ago about the relationship between harm reduction advocacy and the disease model.

For harm reductionists, addiction is sometimes viewed as a learning disorder. This semantic construction seems to hold out the possibility of learning to drink or use drugs moderately after using them addictively. The fact that some non-alcoholics drink too much and ought to cut back, just as some recreational drug users need to ease up, is certainly a public health issue—but one that is distinct in almost every way from the issue of biochemical addiction. By concentrating on the fuzziest part of the spectrum, where problem drinking merges into alcoholism, we’ve introduced fuzzy thinking with regard to at least some of the existing addiction research base. And that doesn’t help anybody find common ground.

UPDATE: I suppose it comes down to whether one sees MI as a complete treatment.

No one would ever consider MI a treatment for cancer, but we might think of it as good practice to engage patients into treatment.

If you see your patient’s SUD as a behavioral issue, MI is the complete package.

If you see it as a disease, for which there are effective treatments, it’s a treatment engagement model.

Provided by Michael Hooper, Veteran and SMART Recovery State Outreach Director for Ohio

Through my journey with SMART Recovery, I have seen certain tools hold immediate weight with the participants of the Veteran and First Responder communities frequenting my meetings. One of the defining reasons why these particular tools ring true to so many of them right away, I believe, is the fact that these tools have the ability to be used in a practical manner almost immediately. Many of the SMART Recovery tools, such as the ABC tool, need time and focus to be properly applied. Based heavily off of CBA techniques, tools such ABC are meant to be utilized in a manner where the participant has time to analyze and deconstruct certain life situations in order to break down the root of a problem. Though highly effective and indeed practical, a tool such as this takes time to master before it can be used in an expeditious manner.

The tools I am including have been proven to not only be useful in a number of different life scenarios (not just addiction related) but can also be used with little to no experience in recovery. Veterans and First Responders adhere quickly to this type of methodology due to our training being similar in many regards. They are expected to comprehend many different training aspects with minimal instruction as these techniques are meant to be used in strenuous situations where cognitive thinking may be impaired. As a result, participants are forced to rely on instinctual reaction or “muscle memory”, so to speak. The following tools can be regarded as the “muscle memory” tools of SMART Recovery as they are easily learned and can be utilized and practiced almost immediately upon assimilation.

Hierarchy of Values (HOV)

A tool asking the participant to identify what is most important to them within their lives. This tool is helpful to aid the participant in focusing on what is most valuable to them and their motivation to create change in their lives, thus contributing to Point 1 of SMART: Building and Maintaining Motivation.

Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA)

This tool outlines the pros and cons of the participant’s addictive behavior, and the same for practicing abstinence from that particular behavior in their life. What is unique about this method for SMART Recovery is that it also defines whether or not these traits have short or long-term effects on their lives. The immediate usage of this particular tool is obvious and, therefore, has been held in high regard by participants.

Disputing Irrational Beliefs (DIBS)

Thoughts can affect our emotions, and our emotional states can influence our actions. Learning to identify unhelpful thoughts and defusing them before they become problematic, is one of the first skills we value in the SMART Recovery Program. Learning how to identify whether a thought is logical, based in fact, and/or is helpful to our current state of being in recovery, can be an essential tool for combating urges, cravings, and triggers; this is Point 2 in our Program.

Deny/Delay, Escape, Avoid/Attack/Accept, Distract, Substitute (DEADS)

One of the most effective tools in the SMART Recovery arsenal for coping with urges and cravings, in my opinion, is the DEADS tool. The DEADS tool is helpful because it is what I like to classify as a “Crisis Management Tool.” This tool can be used with little experience in recovery, and offers multiple pathways to combat an occurring urge or craving.

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Although we often talk about individual drugs and drug use disorders in isolation, the reality is that many people use drugs in combination and also die from them in combination. Although deaths from opioids continue to command the public’s attention, an alarming increase in deaths involving the stimulant drugs methamphetamine and cocaine are a stark illustration that we no longer face just an opioid crisis. We face a complex and ever-evolving addiction and overdose crisis characterized by shifting use and availability of different substances and use of multiple drugs (and drug classes) together.

Overdose deaths specifically from opioids began escalating two decades ago, after the introduction of potent new opioid pain relievers like OxyContin. But actually, drug overdose deaths have been increasing exponentially since at least 1980, with different substances (e.g., cocaine) driving this upward trend at different times. Overdose deaths involving methamphetamine started rising steeply in 2009, and provisional numbers from the CDC show they had increased 10-fold by 2019, to over 16,500. A similar number of people die every year from overdoses involving cocaine (16,196), which has increased nearly as precipitously over the same period.

Although stimulant use and use disorders fluctuate year to year, national surveys have suggested that use had not risen considerably over the period that overdoses from these drugs escalated, which means that the increases in mortality are likely due to people using these drugs in combination with opioids like heroin or fentanyl or using products that have been laced with fentanyl without their knowledge. Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid (80 times more potent than morphine) that since 2013 has driven the steep rise in opioid overdoses.

During the last half of the 1980s, when cocaine surged in popularity, many overdoses occurred in people combining this drug with heroin. The recent rise in deaths from co-use of stimulants and opioids seems to reflect a similar phenomenon. According to a recent examination of barriers to syringe services programs published in the International Journal of Drug Policy, staff at some programs report that increasing numbers of individuals are injecting methamphetamine and opioids together. Some also report that individuals are switching from opioids to methamphetamine because they fear the unpredictability of opioid products that may contain fentanyl (even though methamphetamine may be laced with fentanyl too).

A 2018 study by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and published in Drug and Alcohol Dependence found that methamphetamine use has increased significantly among people with an existing opioid use disorder (OUD). People with OUD in their study reported substituting methamphetamine for opioids when the latter are hard to obtain or are perceived as unsafe, or that they sought a synergistic high by combining them. People who purposefully combine heroin and cocaine or methamphetamine report that the stimulant helps to balance out the soporific effect of opioids, enabling them to function “normally.” However, the combination can enhance the drugs’ toxicity and lethality, by exacerbating their individual cardiovascular and pulmonary effects.

Much more research is needed on the co-use of stimulants and opioids as well as how their combination affects overdose risk. Unfortunately, death certificates do not always list the drugs involved, and when they do, they may not always be accurate about which drugs principally contributed to mortality, making it difficult to know exactly the role opioids and stimulants play in mortality when people deliberately or unknowingly take the two together.

Overdose is not the only danger. Persistent stimulant use can lead to cognitive problems as well as many other health issues (such as cardiac and pulmonary diseases). Injecting cocaine or methamphetamine using shared equipment can transmit infectious diseases like HIV or hepatitis B and C. Cocaine has been shown to suppress immune-cell function and promote replication of the HIV virus and its use may make individuals with HIV more susceptible to contracting hepatitis C. Similarly methamphetamine may worsen HIV progression and exacerbate cognitive problems from HIV.

The use of methamphetamine by men who have sex with men has been found to be an important factor in the transmission of HIV in that population. According to a new study in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes by researchers at the City University of New York and the University of Miami, more than a third of the gay and bisexual men in their sample who acquired HIV in a 12-month study period reported that they used methamphetamine both before and during that period. Among the variables examined, methamphetamine use was the single biggest risk factor for becoming HIV positive, pointing to use of this drug as an important target for intervention in this group. Another NIH-funded study by a team at the University of California San Francisco School of Nursing published in the Journal of Urban Health in 2014 found that delivering cognitive-behavioral therapy for SUD as a harm reduction measure reduced stimulant use and sexual risk-taking behavior in a sample of men who have sex with men.

For now, the best available treatments for stimulant use disorders are behavioral interventions. Contingency management, which uses motivational incentives and tangible rewards to help a person attain their treatment goals, is the most effective therapy, particularly when used in conjunction with a community reinforcement approach. Despite its effectiveness for treating both methamphetamine and cocaine use disorders, contingency management is not widely used, stemming in part from a policy limiting the monetary value of incentives allowable as part of treatment.

Currently, there are no approved medications for the treatment of stimulant use disorders, but hopefully that will change in the not-too-distant future. Multiple NIDA-funded research teams have been hard at work, in some cases for many years already, testing new medication targets as well as immunotherapies for methamphetamine addiction, such as vaccines.

Linda Dwoskin, a NIDA-funded researcher at the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy, is developing compounds that will alter the function of molecules called vesicular monoamine transporters that affect how neurons recycle dopamine and that are targets for methamphetamine’s activity, in order to reduce craving and relapse in people addicted to the drug. (Her two-decade quest to develop a medication for methamphetamine addiction is chronicled in a multi-part series in NIDA Notes—the most recent installment is here.)

Apart from medications, another novel approach being tested to treat several substance use disorders is compounds that recruit the body’s own immune system against specific types of drugs, or the direct delivery of antibodies to neutralize a drug’s effects. A team at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and the biotech company InterveXion Therapeutics is currently conducting Phase 2 trials of a monoclonal antibody capable of holding methamphetamine in the bloodstream and disabling its entry into the brain. (A recent NIDA Notes series also details this research program.)

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated stresses have made the need for new prevention and treatment approaches more urgent. Researchers at the Department of Health and Human Services and Millennium Health recently published in JAMA that since the beginning of the national emergency in March there has been a 23 percent increase in urine samples taken from various healthcare and clinical settings testing positive for methamphetamine nationwide, a 19 percent increase in samples testing positive for cocaine, and a 67 percent increase in samples testing positive for fentanyl. Another recent study of urine samples by researchers at Quest Diagnostics, published in Population Health Management, found significant increases in fentanyl in combination with methamphetamine and with cocaine during the pandemic.

Efforts to address stimulant use should be integrated with the initiatives already underway to address opioid addiction and opioid mortality. The complex reality of polysubstance use is already a research area that NIDA funds, but much more work is needed. The recognition that we face a drug addiction and overdose crisis, not just an opioid crisis, should guide research, prevention, and treatment efforts going forward.

Background

David McCartney wrote a great post about the PHP model of care that addicted physicians receive and its outstanding outcomes.

David framed the PHP model as the gold standard treatment. I also frequently call PHPs the gold standard.

I recently shared an interview with Robert DuPont discussing his discovery that his methadone patients were dying of alcoholism. This prompted David to look more closely at the relationship between opioid use disorder and alcohol use disorder.

All of this raises questions about the nature of the problem and the target for the treatment. In the case of addictions, should we think about substance use problems as discrete disorders characterized by problems with a particular substance? For example, does someone addicted to alcohol, opioids, and cocaine have 3 disorders (AUD, OUD, CUD)? Or, do they have one disorder (drug addiction)?

Brian Coon responded with a great and provocative post asking whether it’s accurate to describe any current treatment as a gold standard.

In his post, Brian points out that advocates, researchers, physicians, and public health professionals often call opioid agonist treatments the gold standard for Opioid Use Disorder.

Brian wonders whether anything should be called the gold standard when the norm in addiction treatment is failure to adequately address smoking. He zeroes in one 2 big concerns about this failure. First, the illness and death caused by smoking. Second, can we say we’re effectively treating their addiction while we’re not adequately addressing their addiction to tobacco?

(Check these out for previous posts from David and Brian on tobacco/nicotine.)

Gold standard?

Should PHPs be called the gold standard? Let’s look at the definition.

The best or most successful diagnostic or therapeutic modality for a condition, against which new tests or results and protocols are compared.

McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine

This definition suggests that the designation is relative to other treatments, rather than an indication that it’s the best treatment possible, so use of the term seems appropriate.

The label has been applied to both PHPs and opioid agonists. Which should be called the gold standard?

Well . . . the definition has 2 parts: being the most successful treatment, and being the benchmark against which other treatments are compared.

Most successful treatment? – I’d say that PHPs could make the case for being the most successful treatment.

Benchmark? – In practice, it’s very clear that agonist treatments are the benchmark for opioid use disorders.

Availability? – Other definitions describe the gold standard as the “best available” treatment. The PHP model is not widely available, but agonists are.

Now, I don’t believe Brian was focused on technical application of the definition of gold standard. Rather, he was focused on our blind spot with smoking while more people die of tobacco related illness than from opioids or COVID-19.

The problem of tobacco

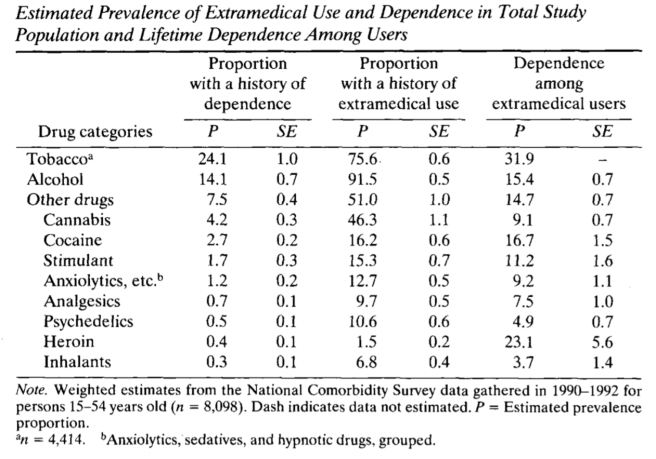

Tobacco and nicotine addiction has interested and confused me for as long as I’ve been interested in addiction.

The case for aggressive treatment of tobacco dependence among SUD treatment recipients is clear and compelling. Consider the following:

- It contributes to more illness and death than alcohol and all other drugs combined.

- Rates of tobacco use among addiction treatment seekers is more than 5 times the general population.

- People with other substance use problems have greater difficulty quitting tobacco.

- Most smokers in addiction treatment would like to quit.

- Quitting smoking during treatment is associated with better treatment outcomes.

- Research has identified tobacco related illness as the leading cause of death for people who had been treated for alcoholism.

Despite all of this, we’ve failed to impact tobacco use in ways that correspond with its threat to recovery and health. Why?

Further, when systems respond in ways that treat tobacco as a serious threat to health and recovery, it evokes intense resistance.

Nicotine addiction is weird

Why do we fail to impact tobacco use in ways that correspond with its threat to recovery and health?

There are some obvious potential explanations–indifference, denial, avoidance, etc. These all undoubtedly contain some truth. And, I think we treat tobacco differently because there are noteworthy ways in which it is different.

- Tobacco does not cause the kind of euphoria we associate with other addictive drugs.

- Yet, it has a higher “capture rate” than cocaine, heroin, and alcohol. (capture rate = the % of users that will become chronic users of the substance)

- It isn’t associated with the kind of short term impairment in cognitive or motor function that we see with other substance use.

- It isn’t associated with the kind of role impairment we see in other addictions.

- Its most serious consequences are delayed by decades and have a very gradual onset.

- It’s a legal substance and, while use may be restricted in certain places, its use isn’t generally prohibited before or during work hours or while driving.

- Its legal status and its widespread use in the recovering community complicate efforts to simultaneously facilitate involvement in the recovering community and abstinence from tobacco.

- While there is growing empirical knowledge about the adverse effects of smoking on addiction treatment outcomes, this appears to be outside of the awareness of the user and those around them. Almost no one attributes their relapse to tobacco use.

- While there is growing empirical knowledge about the adverse effects of smoking on addiction treatment outcomes, the recovering community’s experience is people achieving decades of recovery while continuing to smoke.

- We’ve gotten millions of people to quit with tools like taxation and social control around where and when people can consume tobacco.

- I haven’t seen evidence that these people moved on to other substances.

- Strategies like taxation and social control seem inadequate to impact other drugs in the same way.

- People in recovery often report that the strategies that helped them stop using other drugs are not very helpful with tobacco.

What, exactly, do we really care about?

Much of Brian’s attention is on the deaths and illness associated with tobacco use. What if we were able to minimize deaths and illness? Would we still care? How much?

It’s not difficult to imagine a future where vaping completely replaces tobacco and is regulated in such a way that the risks to physical health are minimal.

I know a handful of people who quit smoking with nicotine gum and have never stopped using nicotine gum, continuing to use it for years.

Would we still question treatment that doesn’t center nicotine? Would we raise questions about the quality or completeness of individual recovery?

We also know that heavy caffeine consumption is common in the recovering community–enough to result in a withdrawal syndrome. Should we consider centering this in addiction treatment and recovery?

Wrapping up

I’m not, in any way, dismissing these concerns about our failures to address tobacco in treatment and communities of recovery. (I’ve preached about this for more than a decade.)

We’ve put a lot of energy into the argument that tobacco is no different from other drugs, but I think that part of the reason we’ve made so little progress is because nicotine is different in some important ways.

I wonder if exploring, identifying, and acknowledging the ways nicotine is weird and different will help us improve our efforts.

Les Waite is a veteran and a clinical psychologist at the Albany Stratton VA Medical Center in Albany, New York. His struggles with addiction lead him to SMART Recovery. Now, he uses the SMART tools daily in his practice for veterans.

In this podcast, Les talks about:

- His educational resume that includes learning the teachings of Alfred Adler

- Serving in the military during the first Gulf War

- Seeing his comrades come back from deployment with trauma issues and finding limited professional resources to help them

- How trauma and substance use disorders are linked

- His owns struggles with addiction

- Being introduced to SMART and why he fell in love with the program

- Why the VA hospitals’ programs dovetail beautifully with SMART’s teachings

- His “been there, done that” connection with patients

- Why the structure and order of the SMART program is effective for veterans

- Playing Jonny Appleseed in the VA hospitals by starting SMART meetings everywhere he goes

- Motivational interviewing and the stages of change model

- Having honest, genuine dialog with his patients about the reasons they are seeing him

- Reconnecting a veteran to their own values using the hierarchy of values tool

- His post-COVID goals of launching more SMART meetings for veterans and in his community

Additional references:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.