Image

Kevin Minnick is the SMART Recovery Regional Coordinator for Indiana. He is also a probation officer for Hancock County. In this podcast, Kevin talks about: How being a professional golfer paid for his master’s degree in counseling Seeing an ad for SMART Recovery in an underground newspaper in the 1990s How working in the chemical dependency unit was luck of the draw Recognizing that many […]

Kevin Minnick is the SMART Recovery Regional Coordinator for Indiana. He is also a probation officer for Hancock County. In this podcast, Kevin talks about: How being a professional golfer paid for his master’s degree in counseling Seeing an ad for SMART Recovery in an underground newspaper in the 1990s How working in the chemical dependency unit was luck of the draw Recognizing that many […]

Radical empathy is not about you and what you would do in a situation that you have never been in and perhaps never will. It is the generosity of spirit that opens your heart to the true experience and pain and perspective of another. . . . The work that goes into learning another person’s reality opens up new ways of seeing the world . . . You gain a greater comprehension of people and systems that may otherwise confound you . . . radical empathy does not necessarily mean that you agree but that you understand from a place of deep knowing. In fact, empathy may hold more power when tested against someone with whom you do not agree and may be the strongest path to connection with someone you might otherwise oppose.

There’s been a lot of attention devoted to Biden’s statements on drug policy and people who use drugs. I don’t know that these are representative, but this is how I’d describe the reactions in my inboxes and feeds:

For many, it is beyond comprehension how a smart and knowledgeable person could hold love for addicts, want to prevent addiction, believe no one should go to jail for a drug problem, and want to maintain criminal penalties for drug charges.

It is beyond comprehension if you have a certain world view and immerse yourself in certain subcultures.

However, if you attend meetings of community coalitions full of family members who have been affected by addiction, Biden’s statements will be be familiar and the logic will be obvious, even if you don’t share these views.

People who have suffered along with an addicted child or loved one often bring a different perspective than academics, libertarians, activists, etc. They often don’t see it as a choice, a civil liberties issue, or something secondary to social issues.

They see their loved one out of control, slipping away, in frequent danger, and engaged in a constant struggle with an illness that seems determined to destroy/steal/replace/disable the person they love. The behavior we see in their addiction is not their true self. They are desperate for something, anything, to interrupt this process.

Further, it’s often infuriating to them that so many experts have a lot to say, but look a lot like passive observers, often fail to acknowledge their loss, fault to see that person making these “choices” is not their true self, and don’t offer an path to bringing their loved one back to themselves and their families.

This post isn’t about Joe Biden or his drug policies past, present, or future, though those are topics worthy of exploration. This post is more about the head scratching and exasperation I read about his statements and positions. If you step outside of your own ways of knowing, your own perspective, and spend time around parents who feel helpless and scared for themselves, their children, and grandchildren, you can hear Joe Biden as a father struggling with the reality that there are no easy answers.

UPDATE: These are people who have to live with contradictions. Many of them simultaneously hold space for the following:

Are people drinking more or less in the UK since the pandemic started? The answer is ‘both’. While overall sales of alcohol are down (sales receipts from HMRC show a 2.4% drop Apr-July 2020), it looks like those who were drinking in the most hazardous fashion previously, are now drinking more. The British Medical Journal identifies a particular subsection of at-risk drinkers:

…those on the brink of dependence during lockdown and beyond. For them, dependence will be triggered by bereavement, job insecurity, or troubled relationships.

BMJ 2020 ; 369

This week, the journal Addiction published data on the impact of the Covid-19 lockdown on smoking, drinking and attempts to quit. What did they find?

Lockdown was associated with increases in high‐risk drinking but also alcohol reduction attempts by high‐risk drinkers. Among high‐risk drinkers who made a reduction attempt, use of evidence‐based support decreased and there was no significant change in use of remote support.

In other words, risky drinking got worse, people wanted to do something about it, but there was less treatment-seeking or treatment available. The authors also warn that increased consumption is likely to put people at risk of covid-19 and will put strain on already-stretched services. They call for increased public health messaging.

The Institute for Alcohol Studies (IAS) has also just published an excellent briefing which captures the most recent data from surveys and studies.

It also makes comment on treatment: ‘Changes in referrals for and uptake of alcohol treatment are concerning but are typical of a wider pattern across healthcare. For alcohol, it is important to consider this in the context of future demand in an already stretched system, particularly given that one study found high risk drinkers were over twice as likely to make a serious attempt to reduce drinking during lockdown compared with before.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists has estimated from PHE’s data that 8.4 million people are now drinking at higher risk levels. The College warned that addiction services are not equipped to cope with a post-pandemic surge in demand for alcohol treatment, following years of cuts.’

In Scotland, where there is a long history of negative consequences to communities, families and individuals from the nation’s heavy drinking, there are fears that the reduction in alcohol consumption associated with the hard-fought introduction of minimum unit pricing is being adversely affected by the pandemic. Concerns have also been raised about the impact on children of increased home drinking by parents during the pandemic’s restrictions and of increased domestic violence fuelled by alcohol.

Scotland on Sunday ran a feature last month which I recommend. Called ‘The coronavirus hangover and Scotland’s alcohol timebomb’, it captures some of the challenges and implications for the country. They summed up the situation:

It is, in short, a perfect storm; the kind feared by governments and public health experts. The signs are that in Scotland – a nation hardly revered throughout the world for its health outcomes – the crisis is exacerbating our long-standing problem relationship with alcohol.

Scotland on Sunday 27.9.20

What about treatment? Well, despite direction from the Public Health Minister that treatment services should remain open in the pandemic, closures did happen, and capacity continues to be affected. All of which adds to the ‘timebomb’.

Movendi, an international social movement for development through alcohol prevention published an alarming must-read policy report last month about the situation in Scotland which concluded:

Alcohol harm is rising across the country and the deficiency in alcohol services is adding fuel to the fire.

Movendi

We have a crisis, which seems likely to provoke yet further crises in terms of increased presentations of alcohol use disorders and all that means. The recurrent themes from multiple observers of increasing problems and a treatment system not prepared, need to be addressed.

A commendable amount of effort has gone into, and continues to go into, tackling Scotland’s drug deaths problem. While treatment resource has been increased, the focus has been on the opiate problem. It would be good to see similar elbow grease applied to tackling our almost-certain-to-grow alcohol morbidity and mortality – already higher than our drug deaths, but receiving only a fraction of the attention.

Ian Gilmore and Ilora Finlay, in an BMJ editorial sum up nicely:

Presentations of alcoholic liver disease, already increasing before the covid-19 crisis, will rise further. A similar surge will occur in the need for alcohol treatment services, which are traditionally an easy target for cuts when finances are tight. We know that investing £1 in alcohol treatment services will save £3, as well as directly helping affected individuals, often the most vulnerable in society

They conclude with an exhortation to look to national, and consequently personal, recovery:

This time, let’s be ready. Tackling alcohol harms is an integral part of the nation’s recovery.

“We are only as strong as we are united, as weak as we are divided.” ― J.K. Rowling

This is a political post; I hope readers give me a chance and hear me out. As I have said before, I am a student of history, and have spent some time learning about the history of addiction and recovery in America. History can teach us important and relevant lessons. Over the last sixty years or so, we have tended to take a few steps forward and then a few steps backwards in respect to supporting recovery efforts. One thing is true however, and that is when we have managed to move things forward, it was because of broad, bipartisan support.

This is true even now in our hyper partisan political climate. In 2018, HR 6 the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act passed the in the US Senate 99 – 1 and in the House of Representatives 396 – 14 before being signed into law by President Trump on October 24th, 2018. That is significant in our current political climate.

This is because addiction and recovery has long been seen as a nonpartisan issue. Addiction impacts everyone. There are great advocacy points that support expanding access to treatment and recovery support services that make sense from Conservative, Liberal and Libertarian perspectives.

When I reflect on this – I think that this is largely a factor of the lack of partisanship in recovery. In the culture of the recovery community, we all depend on each other, without regard to political beliefs. Thinking of a well-known member of Congress who had a very public arrest a number of years back. In reading back on his accounts of his journey in recovery, it was a member of Congress from the other party who quietly reached out to help him. They formed a deep connection based on their common purpose of recovery.

This is our recovery culture.

The one thing that I would want people to know about me is that political perspective are way in the back seat to recovery for me. I suspect that is true for the majority of us. If you have political views that are different than mine, I respect you, hold you in positive regard and want you to know that I am there for you in your recovery journey in any capacity that I can. We have a great deal of common ground, and I recognize that my own recovery is supported by people who have different political beliefs than my own. Said another way, my very life depends on people with different political views than my own. I think that this is true for the vast majority of the recovery community, and it makes me proud of us and what we stand for.

Recovery must always come before personal ideology.

It is also important to note in this hyper partisan environment, if we ever lost that, we would lose all the gains we have made in supporting treatment and recovery efforts over my lifetime. I see policymakers with vastly different ideologies coming together on common ground to support treatment and recovery efforts. We must acknowledge and protect that common ground at all costs.

We have a long way to go to create a world where recovery is seen as the probable outcome for people with substance use conditions if they are given the proper care and support. This is our common ground and it is important for us to maintain our singleness of purpose.

We cannot afford becoming a partisan football. We all have a roll in this. Think twice before posting things that may be seen as hyper partisan on social media that may reflect back on the recovery community. If you run a recovery organization and are asked to provide information to a candidate or a political group, make sure you reach out to the other candidates and groups from the other “side” and offer equal support. Pay attention to hyper partisanship in recovery circles and educate people about the risks of dividing our community and becoming viewed as partisan.

We are indeed standing on the shoulders of giants – we must not fumble in our efforts to expand recovery by getting mired down in hyper partisanship. We owe this to the next generation. We stand to lose everything if we fail to stay above partisan politics.

My name is David McCartney and I am a Scot. I live in the southern uplands of Scotland, but I work in the Central Lowlands, which is the middle part of the country.

I’m a doctor who specializes in addictions, and I work for the National Health Service, and part of the Health Service which is focused on mental health, so addictions come under that. I am the clinical lead in the service called LEAP, which stands for Lothians and Edinburgh Abstinence Program, and that is a quasi residential rehab. Normally, when it’s not COVID times, we take around 20 patients at a time. We treat about 100 people a year in a three-month quasi residential treatment program, which is based on the therapeutic community model of treatment.

Well, the patients that we treat don’t live on the premises where the treatment is delivered so the living accommodation is separate from the treatment accommodation. And it’s a partnership approach, so the city of Edinburgh council provide the staff team which looks after the patients in the evenings, and at the weekends, and overnight, and the NHS, National Health Service team, look after the patients during the day and Saturday morning.

Yeah. I’m in recovery myself, have been in recovery for many years now. I guess that’s probably the main reason that I’m working in addiction treatment because of that experience. When I was in my early 40s addiction had brought me to my knees, I was in inner-city GP, in Glasgow, in the west of Scotland, and couldn’t really get my head around why somebody from my background, with my training, and resources couldn’t stop drinking. I had two episodes of treatment, the first was very focused on medication, on getting off the alcohol, so it felt quite a medical approach. All that really happened was that alcohol was taken away, but life didn’t seem to get an awful lot better. It was a lonely kind of recovery, looking back. The second time around, I got introduced to other people who are in recovery, which was a revelation, especially other doctors, ’cause I was carrying a huge amount of professional shame associated with my drinking and not being able to stop.

I went to a residential treatment and I didn’t really know what residential treatment was, despite having looked after people with alcohol and drug problems, some of whom had gone to residential treatment, but I had no idea what they were going to. In a sense, I had no idea where I was going to either. I might have thought twice about it had I known, but it was a transformative experience. It really turned my life around. It’s such a big impact. That’s where the seeds were sewn to change career direction and to do something with the vulnerable population in Scotland, people with alcohol and drug problems, who maybe didn’t get the same privileges as me, as a middle-class doctor who got to go to a fancy residential treatment center. Most people in Scotland don’t get that opportunity, so I wanted to try and make that different. That’s the background to my personal experience and a bit about how it intertwines with my career, and my career choices.

When I got better from my own addiction, I retrained and went back to university and did a Master’s degree in alcohol and drug studies. I wanted to work in the field. So, first of all, I got a little bit of experience working in a residential treatment setting. In Scotland, most of these are either in the third sector, charitable, or non-government organization sector, or private, so I have to go outside of the NHS to get that experience. I did that for a while, and then I came back to work for NHS in addiction treatment. But the addiction treatment clinics I was working in were very focused on harm reduction, which is really important, I am a harm reductionist at heart, but there was precious little time to do any kind of meaningful work. Time with patients tended to be focused on the prescription, and on the medication, and on testing, and all of that kind of stuff, and I wanted to do something different from that in the longer term.

I had an idea… first of all, I had to look to see what the literature said about residential treatment and there wasn’t an awful lot of stuff published in the United Kingdom so I had look elsewhere, to the United States, of course, a little bit from Australia. Then I went to visit some treatment centers and that was really helpful because the people who were running these places were really good and generous at sharing what was working for them and they had done the legwork, if you like, in setting treatment systems up. I then started to write down some of these ideas based on the evidence that I could find, and I started to pitch it to people that were commissioning services. One person picked up the idea and pitched it to the Scottish government who funded a two-year pilot to set LEAP up, and I knew from my visits and talking to people that run other treatment centers that there was precious little around on outcomes. I couldn’t get my head around this to start with it, so much money was going into addiction treatment, but people were not measuring what was happening to their clients. From the offset I decided whether it was going to be a success or not, we would measure what we were doing, and we’d measure what was happening to the people who we’re trying to help. That evaluation turned into a study, which is still ongoing, we’ve still got data for about up to five years after treatment now.

Long story short, the service got funded. We only had two years of funding, so we really had to prove that we were worth the investment in that time, and we were able to demonstrate to government that we were worth continuing funding being given to us, and that’s what’s happened. Ever since we’ve done the same sort of thing with evidence of what we’re doing, and that evidence has helped with funding. So, unlike elsewhere, patients don’t have to seek funding. As you’ll be aware that the two systems of health in the United States and United Kingdom are very, very different, so patients don’t have to seek funding, there are no insurance companies paying for patients to come to LEAP. If you fulfill the criteria for treatment, you’re given a place, you don’t have to worry about the funding for it.

I’ve also done a bit of work for the Scottish government on drugs policy off and on over a few years. More recently, we’re working on looking at the lie of the land when it comes to residential treatment across the whole Scotland. So, our feeling is it’s quite patchy. Some people have reasonably smooth access to it and other people, unfortunately, don’t seem to have access at all. So the Scottish government have set up a working group, which I’m chairing at the moment, which is looking to see really the scope of what’s actually happening, and then to make some recommendations to government. We’re hoping those recommendations will be along the lines of trying to have equity of access across Scotland so that if it’s the right kind of treatment for someone, they’re able to get there. So I guess that’s the answer to the question.

Wow, that’s a good question. Professionally, our patients and their achievements. My team, and a lot of the people I work with they’re in recovery, and they bring something of that into the professional life… a passion I suppose, and the enthusiasm for recovery. And, our service… we’ve managed to achieve a lot to help our patients get where they want to go, and to help keep them there by putting aftercare in place and connecting people up to ongoing sources of support. So yeah, these things… That’s quite a lot of things to be proud of, but professionally, my team, our patients, and the service and what we do with our patients.

I think one of the things that I get to see is people doing well because we provide aftercare for up to two years. Everyone who comes to our treatment service is from the local area, so there is Edinburgh City and then there’s three Lothian counties around Edinburgh and it’s about 800,000 in population. So, people are treated in the area that they are already living in, so when they come back for aftercare, you’re seeing them over a period of time. You’re seeing them doing well, you’re seeing their families, they are coming to the family group, and that feedback is hugely powerful. There’s an excitement to that that comes. I’ve always enjoyed my job when I was a GP in Glasgow, there was a lot of fulfillment and pleasure from that, but this is something different.

I guess you get to see the fruit of our patient’s labors over a long period of time and that’s really encouraging. I remember there was a British researcher that was looking at drug workers in a part of the United Kingdom and he was asking them, “what percentage of your clients, the people you’re working with, what percentage of them do you think will get better over time?” Their estimation was something around 7%, they reckoned only 7% of the people who we’re working with would ever recover. Of course, the actual figure is much, much higher than that. So they had low expectations, not because they were poor practitioners, but because they never saw people getting better. All they saw was people who recycled back in, who relapsed and came back. The people who did well moved out of the treatment service and didn’t need to come back. They would be successes… but they didn’t get to see that. There was no reinforcement. So for me, the reinforcement of seeing the people achieving their goals and maintaining those goals is hugely satisfying–not just satisfying, it’s exciting. I suppose that’s what keeps driving me.

It has affected it profoundly. When the shutdown happened here in Scotland, it was quite dramatic and sudden and there wasn’t much opportunity to plan. Our service was closed very, very quickly at the beginning. We had to wind down people who were in treatments that we had to finish the treatment much sooner than it should have finished, which was really hard because we knew that was putting them at risk. Then there was a period where we weren’t able to operate at all for a few months, and during that time we lost the accommodation (housing) part of the service because it was put aside for public health to use as a kind of isolation center. We’ve been unable to get that back. So, we’ve had to find alternative premises, and we are working with a hugely reduced capacity. Instead of treating 20 people, we’re treating 8 people, which causes its own problems in a therapeutic community environment because you need a certain threshold, a number for it work effectively.

We are trying to increase capacity, we’ve got permission to do that but we don’t have accommodation to do that. So that’s been very, very hard. In addition, just recently, the city of Edinburgh council team who look after our patients after hours, they have been pulled to work in public health as well. So my team have had to move from working 9:00 til 5:00, to going to shifts which they’ve all agreed to do, amazingly. That has meant fewer people available during the day. So it’s been really chaotic. We have adapted, we’ve done our best. Our waiting list has gone up, we’re looking at ways of trying to support people on the waiting list just now. We’ve moved our aftercare program and our family program to digital platforms… amazingly, that’s actually been a success story. We’ve managed to retain most of people through Zoom and other platforms.

We’re now in a situation where we’re trying to prevent harms coming to people on the waiting list. Almost by definition, people who referred to residential treatment from our wider service – most of our referrals come from fellow treatment professionals who are working in the community with people. So doctors and community psychiatric nurses and voluntary sector agencies refer into us and they are referring the people that are probably trickiest and have the greatest burden of problems, and the least recovery capital. Maybe they’ve got co-morbid mental health and physical health issues. They’re sitting on a waiting list, and they are coming to harm. We’ve been monitoring a lot of them that had to be admitted to a hospital for emergency care, some of them been seen in accident and emergency departments, and emergency rooms for emergency treatments. We know some of that’s preventable had we been able to bring them into treatment. So, that’s been really, really hard as a doctor.

We’re doing our best to try to meet these needs but it is very difficult. In addition, of course, there is the other anxiety of trying to keep the patients safe, so we’ve put into provision a lot of things to try and do that. But of course, there is always still a risk when you’re bringing people together in a group when there’s a lot of COVID around in the environment. So we’re doing our best but it has been tough and I suppose it’s been tough emotionally as well as practically. Certainly, there’s a sustained effect over a long, long period of time and there’s no end in sight yet. So… just having to keep supporting each other and look to other ways of supporting ourselves. I’ve recently been getting into mindfulness meditation just to try and get myself a bit more grounded and not so distracted when I come home about what’s going on at work and that’s really helped.

I think the biggest thing – certainly for aftercare patients has been the disconnection. Then, of course, all of the mutual aid groups in Edinburgh and Lothian we have… We have so many mutual aid groups. We have Alcoholics Anonymous. We have got Cocaine Anonymous. We’ve Narcotics Anonymous. We’ve got Smart Recovery UK. We’ve got all of these… There is so much of a resource out there and all the meetings just had to stop suddenly. So, of course, they’ve moved to digital platforms as well which has been effective but some people don’t like digital platforms.

So that’s been hard. I know it’s been hard ’cause we’re hearing stories of how hard it’s been for people, sticking to the guidelines when they desperately need the contact of other people. The other thing is more societal. We have got some early… It’s mostly anecdotal, a little bit of hard evidence that people’s drinking has changed in the pandemic. If you think about people who are not yet patients, some of them have reduced their drinking, but some of the people who were probably problem drinking are now drinking in a more hazardous fashion. That, I suspect will result in more referrals coming into the system. Again, there’s a little bit of anecdotal evidence of that happening in clinics in the community. So I suspect what will happen is we’ll get an increase in referrals coming into treatment, not just to residential treatment but, across the board. And we’ll probably see increased demand on hospital emergency departments because of crisis presentations and such. It’s early days but I think it’s a case of watching the space.

That’s an interesting question. I guess other treatment settings where funding has got to be found before the person can come into treatment… Usually in the United Kingdom that would be through either through health funds or more likely through social work funds. I suspect those services which rely on that kind of funding, some of them will fold because of restrictions and numbers that they’re having to apply at the moment. I hope one of the things that’s happened is… this kind of crisis has forced us to look at our own values of what matters. I think looking after vulnerable people with alcohol and drug problems… I hope that we have a more compassionate approach because people can see that a lot of this is coming out of hurt and isolation, and people losing their jobs, and economic crisis, and so on. So it’s a back to the old thing… You know it’s not a moral thing if you suffer from an addiction, it’s an illness. And, like every illness, it’s affected by the environment people find themselves in. This is a really difficult environment. So I hope that compassion will come out of this. But again, it’s a case of watch this space… we’re in the middle of something we’ve never been in before, so it’s unpredictable.

I suppose it’s linked to what I’ve just said. It’s probably been one of the hardest times as a professional to try and keep that professional hat on, and not be reactive and emotional and so on. A part of me knows I’ve got to allow myself to feel, but it’s been tough. The last few months have been really tough.

I think self-care. As in the United States doctors are regulated, it’s called the Boards in the States, and we have the General Medical Council here. Part of what we have to do is have an annual appraisal, and to re-apply for our license to practice, and demonstrate that we’re able to do that. And, just recently, which I think is a really good thing, we have been advised to look to self-care and to demonstrate how we’re self-caring in our appraisal. I thought it was a really positive move, and it certainly made me sit up and take notice of how I have to care for myself. It’s like that thing when you’re on an aeroplan and you know they say that the masks will drop down, fit your own mask before you help others, you know. I need to self-care before I can really be giving my best to my patients. And, I was aware I wasn’t self-caring, I was fretting and feeling anxious, and struggling a bit, and I’m not feeling the same way now because I’m doing a bit more self-care. I mean for a lot of people who read this or listen to this, that’s probably a pretty obvious thing [chuckle] to do. But sometimes I just don’t bring myself back and think, “You need it to be caring and loving toward yourself as well as the people you’re looking after.”

If I think… What would have the biggest impact across a range of different treatment services? I think this is something that is beginning to happen here in the United Kingdom, is to involve people with lived experience embedded into those systems. It has to be done carefully so that you protect the individuals and don’t abuse the privilege. But, when we first started treating patients, we heard the same thing again, and again, and again when people were coming into treatment–they didn’t know anyone else in recovery. So they’ve never met anyone else who recovered.

Back in our early days most of our patients were heroin-addicted and they’d never seen anyone get better. Then one of my colleagues, who was a Community Psychiatric nurse, told me of someone that we treated who got into recovery, and then maintained that recovery, and is still in recovery today actually many, many years later. The impact that guy had on his community… because none of his peers had ever seen anyone get better from heroin addiction. That made such a profound… All of a sudden we had all these referrals coming [chuckle] in from the same town because people wanted something like what this guy had achieved. And that stuck with me and we developed a peer support program and then we got some funding to apply to someone who’d be our peer support coordinator and look-after the peer supporters, develop a training program, and so on. And I think that if we had people with lived experience, who were trained and supported in other services… at the places where needle exchange is happening, and we’re trying to get people engaged into opioid replacement treatment, and we’re trying to save lives essentially. If you had peer supporters there, people with experience, who’ve maybe been there a few years ago, and delivering the needles, and caring for them, and sharing a little bit of the story at the same time, that would generate hope. And, as you know, as we all know who work in addiction treatment, hope is not a thing, you can’t put it in a bottle and you can’t prescribe it, but you can influence it, you can demonstrate it with hopeful people and people whose lives have been changed.

I’d like to see that… it might be my fantasy to see that role across Scottish Addiction Treatment Services where you had role modeling and enthusiastic recovery of different sorts, and not necessarily one brand, but to give hope to the people that come into our services.

We are pleased to announce the release of our newest Tips & Tools for Recovery that Works! video Role Playing.

Role playing is a great way to prepare and practice overcoming urges in circumstances that maybe problematic (dates, weddings, etc.). This tool can help one envision future urge scenarios in their mind, and then play them out with a friend, in advance, to rehearse the urge situation and create the most desirable non-relapse outcome.

Click here to watch this video on our YouTube channel.

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

Image

Dr. Amy Hauck Newman

Amy Hauck Newman, Ph.D., has been appointed the Scientific Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s (NIDA) Intramural Research Program (IRP) in Baltimore. NIDA is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Dr. Newman has served as NIDA’s IRP Acting Scientific Director for the past two years. She is also Chief of NIDA’s Molecular Targets and Medications Discovery Branch, and Director of the NIDA IRP Medication Development Program. She has coauthored more than 300 original articles and reviews on the design, synthesis, and evaluation of central nervous system (CNS) active agents as potential treatment medications for substance use disorders, with an emphasis on selective ligands for the dopaminergic system. She is also an inventor on several licensed NIH patents.

"Dr. Newman will continue to bring tremendous strength to NIDA’s robust intramural research portfolio," said NIDA Director Nora D. Volkow, M.D. "She has served exceptionally as our Acting Scientific Director, and her valuable work on CNS agents is bringing us closer to new and better medicines for the treatment of addiction."

In 2019, Dr. Newman received the NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein Mentoring Award from the NIH Office of the Director. In 2018, she was honored as a "Remarkable Woman in Medicinal Chemistry" at the 255th American Chemical Society National Meeting. In 2016, she was the first woman to receive the Philip Portoghese Lectureship Award, awarded by the Division of Medicinal Chemistry and the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, American Chemical Society. In 2014, she received the Marian W. Fischman Lectureship Award from the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

Dr. Newman received her doctorate in medicinal chemistry from the Medical College of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University, under the mentorship of Richard Glennon, Ph.D. For her postdoctoral studies, she joined the laboratory of Kenner Rice, Ph.D., at NIH, where she conducted total opiate synthesis as a NIDA-funded NIH National Research Service Award fellow.

"As a career NIH scientist, it is indeed an honor and privilege to lead the NIDA IRP in cutting edge basic, preclinical and clinical addiction science to be translated into the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders," said Dr. Newman.

Dr. Newman officially began her new position at the NIDA IRP on November 22, 2020.

For more information, go to Dr. Amy Newman.

Contact: NIDA press office at media@nida.nih.gov or 301-443-6245. Follow NIDA on Twitter and Facebook.

NIDA Press Office

301-443-6245

media@nida.nih.gov

About the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA): NIDA is a component of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIDA supports most of the world’s research on the health aspects of drug use and addiction. The Institute carries out a large variety of programs to inform policy, improve practice, and advance addiction science. For more information about NIDA and its programs, visit www.drugabuse.gov.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health®

The mention of Philip Seymour Hoffman in Jason Schwartz’s blog post yesterday provoked a memory. Thomas McLellan, a prominent US addiction researcher and policy advisor, lost his son to an overdose in 2008. He wrote a piece in the Huffington Post a few years ago which has stuck with me. A journalist who had interviewed him referred to the late actor Philip Seymour Hoffman as ‘a weak piece of shit’.

Says McLellan:

“Even as I sit here several days later, I am dumbstruck by the callousness, the audacity, and most of all, the ignorance of this comment.”

He goes on to say:

“Overdosing on heroin doesn’t make you a scumbag. Having a drink after 20 years of sobriety doesn’t make you weak. Having an addiction is not a moral choice. In fact, I think it is accurate to say that having an addiction is not a choice at all.”

Thomas McLellan

He points to the research evidence around the disease of addiction and the effects on the parts of the brain governing judgement, inhibition, motivation and learning and points out that nobody has their first drink with the intention of going on to be an addict. He says:

“I wonder how the media or the public would have reacted if Mr. Hoffman had passed away as a result of another disease that he had been struggling against for 23 years? Say cancer? I think the young actor’s triumph over cancer likely would have been celebrated throughout his career as an example of his personal strength.”

He concludes:

“The science is… strong in the case of addictions and it is time that media and public perceptions about addiction catch up with the science about this disease. Until that happens, too many talented and extraordinary people will struggle in silence and die in the shadows of shame.”

(This is a version of a previously published post)

This post was originally published in 2014.

There’s a lot of commentary out there on Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death. Some of it’s good, some is bad and there’s a lot in between. Much of it has focused overdose prevention and some of it has focused on a need for evidence-based treatments.

Anna David puts her finger on something very important. [emphasis mine]

Let’s explain that this isn’t a problem that goes away once you get shipped off to rehab or even get a sponsor—that this is a lifelong affliction for many of us. There seems to be this misconception that people are hope-to-die addicts and then get hit by some sort of magical sunlight of the spirit and are transported into another existence where the problem goes away.

[NOTE – I know almost nothing of Hoffman or the treatment he received from his doctors or anyone else. My comments should be considered commentary on the issues involved rather than the specifics of Hoffman or the help he received.]

What I haven’t heard discussed much is his reported relapse a year or so ago. How could that have been prevented?

From what I understand, this is someone who had been in remission for 23 years. And, it sounds like his relapse began in a physician’s office when he was prescribed an opiate for pain.

Could the outcome have been different if some sort of recovery checkup had been performed by his primary care physician or the doctor who treated his pain?

Could the outcome have been different if some sort of recovery checkup had been performed by his primary care physician or the doctor who treated his pain?

If he had been in remission from some other life-threatening chronic disease, wouldn’t his doctors have watched for a symptoms of a recurrence? Or, given serious consideration to contraindications for the use of particular medications with a history of that chronic disease?

What if he had been asked questions like:

Also, if it’s determined that a high risk treatment (like prescribing opiates to someone with a history of opiate addiction) is needed, what kind of relapse prevention plan was put into place? What kind of monitoring and support?

There are two issues here. One is the lack of research, training and support that physicians get around treating addiction and supporting recovery.

The second issue is the role of the patient.

I listened to a talk by Dr. Kevin McCauley this morning in which he addressed objections to the disease model. One of the objections was that the disease model lets addicts off the hook. His response was that, given the cultural context, there were grounds for this concern. BUT, the contextual problem was with the treatment of diseases rather than classifying addiction as a disease. He pointed out that our medical model positions the patient as a passive recipient of medical intervention. As long as the role of the patient is to be passive, this concern has merit. He suggests we need to expect and facilitate patients playing an active role in their recovery and wellness.

So…this was someone who had been in remission for decades. He clearly had a responsibility to maintain his recovery. At the same time, the medical and/or treatment system has a responsibility to monitor and support his recovery.

I happen to have celebrated 23 years of recovery several months ago. I’m still actively engaged in behaviors to maintain my recovery. (Much like I’m actively engaged in behaviors to keep my cholesterol low.)

In 23 years, has a doctor or nurse EVER asked me how my recovery is going? No. Have they ever evaluated my recovery in ANY way? No.

Do they want to check my cholesterol every so often? Like clockwork.

This is a critical failure of the system and the evidence-base. And, we don’t just fail people with decades of recovery. Even more so, we fail people with 90 days, 6 months, a year, 5 years, etc. Then we blame the approach that helped them stabilize and initiate their recovery when the real problem was that we never helped them maintain their recovery. (Then, too often, our solution is to insist that they get into that passive patient role, just take their meds and let the experts do their work.)

via Another Senseless Overdose.

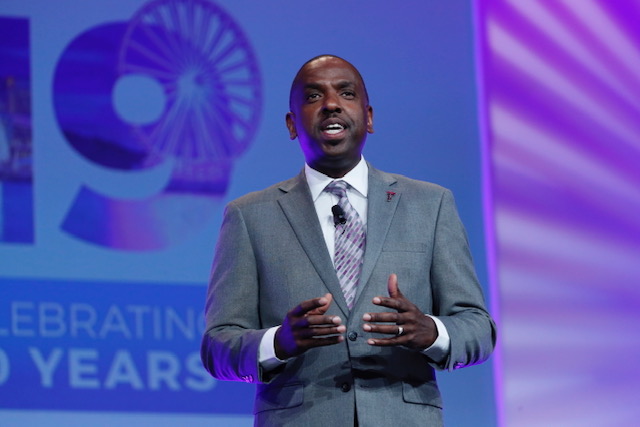

I’m Terrence Walton. I am a husband that just celebrated his 20th anniversary, a father of two small children, and a man who has dedicated his life to two big things. One is the well-being, in every sense of the word, of my family, and then secondly is to help free men and women from addiction – and that includes especially helping people who are helping people get free.

RISE19 Opening Ceremony on Sunday, July 14, 2019 in Oxon Hill, Md. (Paul Morigi/AP Images for National Association of Drug Court Professionals)

RISE19 Opening Ceremony on Sunday, July 14, 2019 in Oxon Hill, Md. (Paul Morigi/AP Images for National Association of Drug Court Professionals)

I’m a treatment and recovery management professional by training. That’s all I’ve ever done in my entire life as an adult. Right now, I am the Chief Operating Officer with the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP). I hope folks know what drug courts are. We call them treatment courts or recovery courts these days. They are actual courts either on criminal calendars or family calendars for men, women, and youth who are involved in the justice system – not because they are hardened criminals but because they are living with addiction or mental illness that is leading to arrests and/or criminal activity. Treatment courts are designed to help individuals get linked up with effective treatment and effective recovery management, instead of incarceration or just probation without the services they need to get and stay on the right track.

Yeah, I do. I’ve done this for a very long time, and I took a couple of years in the middle of my college career to really decide where I wanted to settle, and I settled here. I’ve often wondered what my personal tie-in to this really is. One is that it’s my calling. This is what I am here, here on Earth, to do. And where that calling came from – the personal basis of it – I think some of it is because I have a long history of addiction in my family, both sides of the family. I have a favorite uncle, my mother’s only brother, who struggled with alcoholism his entire life. I have very early memories of him being sort of lost in alcoholism. I remember one time the family was in the car driving around at night. My two brothers and I were very small and in the back seat. My parents were out looking for her brother and they found him. I didn’t know what was going on, Brian, but I remember seeing him. He was sweating, he was talking out of his head, and my father got out of the car and took him into a place and got him a drink – a beer. And I saw him get better. He was himself. I don’t remember if my parents explained to me what that was about, but I never forgot it. And I think that planted a seed. Also, while I’m not a person who is living with a substance use disorder, I’m an ally of men and women in recovery. And I walk my own recovery journey for my issues that I discovered while working professionally in the field. So, in addition to my alliance with men and women in addiction and in substance use disorder recovery, I discovered my own issue and work a daily recovery practice, a daily personal practice.

I’ve been doing this for as long as I’ve been doing anything professionally. For me that’s over 30 years. I worked for about 5 or 6 years, maybe a little more, doing direct services initially as a tech in a residential adolescent treatment center. And that’s a fancy word for “I observed urines, checked patients’ belongings at intake for contraband, and spent time with young people to keep them from getting into it.” It was there I discovered I really connected with the kids and the work I was doing. I was good at it. I didn’t have much training at that point – maybe two years of college – but I discovered that this is what I want to do. I want to run a place like this. After my direct service time, I soon had the opportunity to take over as director of an adolescent treatment program – earlier than I probably should have, based on how little experience I had. But things went well there. So, I spent the early part of my career directing community-based addiction treatment programs. And about 17 years ago, I became director of treatment for the pre-trial services agency for the District of Columbia. That’s a large pretrial services agency here in Washington, DC. It’s actually a Federal agency. And they had and have a drug treatment court. That’s how I became involved in the drug court world, and very soon I got connected with the organization where I am now – NADCP – as a senior consultant advising them on treatment and recovery matters, and training for them all over the country. I was eventually persuaded to leave my federal position to come on board here in this role. So I’ve had the pleasure of working with hundreds and hundreds of mostly young people and also their families, living with addiction, and probably thousands of professionals who are helping people receive and succeed in treatment and enter long-term recovery. So, I’m enjoying my career – it is what I’m here to do.

Well first of all, and this is for real, my wife and I started our family late, so we have two small kids— my son just turned four and my daughter just turned seven. I’m convinced that my children are very aware of how much they are loved and how much they and how amazing they are, and that matters to us. My wife and I both believe that this is critical to wellness. And it’s never too late to have a happy childhood, so people can always catch up later. But there’s damage done when children aren’t safe and secure and loved unconditionally. I know that my children feel that and I’m very proud of that. Professionally, when I think “proud”, it’s really gratitude. I’m very grateful that God has given me the ability to do the thing that matters to me and do it really well. And I’m grateful and proud of the influence I’ve been able to have broadly, but especially in the justice system as it relates to working with men and women who are in the middle of addiction and desperately in need of recovery whether they know it or not.

You know, I can’t imagine doing anything different. There are certainly opportunities that have arisen for me to do something other than work in the addiction and recovery field. I’ve always easily said “No” to those. Because it is very clear to me –there is no more important and critical work. I am so aware that there are men, women, and young people who are trapped in addiction – they are in bondage – and so much of their potential, what they could do for themselves, their families, our communities, this world, is hampered by the fact that they are trapped and can’t keep the promises they have made to themselves, let alone anyone else. And that bothers me. This world and especially this country we’re living in, Brian, is a mess. And there are people in recovery who will be a part of how we get better as a country. I am convinced of that because real recovery requires self-reflection, acceptance of those who are different, humility, and service. And that’s what this country is going to need to really recover, not just from this pandemic, but from the unrest over injustice and racism, and the resentment of people in certain communities feeling left behind and forgotten. We need people in recovery who possess the values required for us to do well, for this country to heal. So I keep doing this because I know that I’m making investments in our future, and making investments in people being able to at least get on the same journey that we’re all on – trying to live our purpose, find meaning, and make this a better world.

There’s no question I didn’t see this pandemic coming. No one did. I had never really given this possibility much thought. I suppose I wasn’t a good student of history – of the previous pandemics. I help lead this organization and we spend lots of time out, throughout the country and the world working directly with teams, court, states, and nations who are implementing treatment courts. Even though I am Chief Operating Officer and my job is based here in the Washington DC area, I spend probably a third of my time on the road: trainings, speaking, and working hand-in-hand with organizations and systems who are trying to help people enter in recovery in a lasting way. Other than webinars from time-to-time, we’ve been accustomed to doing business in-person. We have a significant on-line presence at allrise.org and at ndci.org. However, the bulk of our work is face-to-face and I really value that. I’m a face-to-face kind of guy. We’re that kind of operation. We had to adjust. We had to figure out and accept “This is what is. And this is going to be our new world for a while.” Our mission doesn’t change. My calling doesn’t change. People don’t stop needing help. Programs don’t stop struggling. And so we had to adjust. We closed our physical office for nearly all staff in mid-March. Our office is closed now and we’ll remain closed throughout 2020 at least. I still come in most days, as does one other person but everyone’s working hard from where they are. As the COO, I had to operationally reorganize to be sure the job could get done, and that our team had the resources they need. Only a third of us teleworked beforehand, and that went up to nearly 100 percent. I had to personally focus very heavily on my operational duties, to be sure that progress on our critical mission could continue. Personally, I just had to get used to training and assisting virtually. And fortunately, I remembered that I’m pretty comfortable on camera and found ways to connect that way too. I’m looking forward to a world where we can return to some in-person work. But even as it is, I don’t think we’re missing much.

I’m seeing significant impacts. And some of the impacts I don’t think we even know yet; we’ll know when we look back and analyze what’s happened to people. This situation has given me the opportunity to have more one-on-one conversations with treatment providers, and teams, regarding their struggles. Many of the people they serve, the clients they serve, the families they serve, are struggling. They had been doing well in treatment court because they have the structure of the court and all that provides, especially the accountability and the reinforcement they get from a judge saying, “Great job! Keep it up!” They’ve sometimes been able to benefit from the best treatment they’ve ever gotten. More than what they might have gotten if they just walked in off the street from somewhere. Perhaps they were finally able to integrate into the larger recovery community. And then, suddenly much of that dropped off. Some treatment courts had to suspend operations altogether for a little bit just to re-group, to figure out how they do court virtually, consistent with laws and regulations. Many treatment providers hadn’t previously delivered telehealth and so they had to figure out how to do that. Part of what sustains many who are early in their quest for abstinence and recovery is drug testing. Many programs understandably had to suspend that. So the suspension of these kinds of things or the lessening of them I think had some big impacts. I talked with a program a couple of weeks ago who has not yet resumed services. That’s unusual – most have. But they haven’t. I fear once that program is able to resume, those participants who they can find are going to needs lots of work to help them get back on track. Another program, during their very brief shut-down, lost three individuals. I mean three individuals died. With one, they are not certain if it was drug-related or not; they know the other two were. Those kinds of impacts are real for the people they serve. Finding ways to adjust and navigate this has been a real challenge. My organization’s job is to figure out how to help them. And we didn’t know, so we had to figure that out for ourselves first. They need resources. We provided a number of webinars and publications. We added a full page to our website, just about getting through the pandemic. Because as I mentioned earlier, pandemic or not, addiction continues. One more thing is this – I remember driving through some of the areas in DC where people who are struggling with addiction get their drugs. And I observed that the drug trade was alive and well. So that didn’t go away, and people still needed help. Yes, there have been significant challenges.

There are probably some good things that have come out of this, but let me first talk about some of the other kinds of effects. I am concerned there may be individuals who are just lost to us – I mean long-term. There are people who were doing well in treatment court and they’re just lost to us. I hope they find a path somewhere else, but for some that’s not going to happen. For some already that’s been clearly the case. I also recognize that the money that the state and Federal governments have had to spend to keep people surviving, and the economy, are going to have to be repaid. I suspect when things settle down, and it’s time to pay the bills, that this may result in cuts in areas that are critical for people’s lives, including funding for treatment and recovery management. I’m already thinking about how we advocate collectively to keep as many resources in treatment and recovery as possible. We also need to be prepared to seek more private sources to help pay for what I fear may be a reduction in public funding for this really important stuff.

I have. I’ve mentioned the fact that I’ve gotten better at this. Well, a lot of people have. There are a lot of courts that have, and treatment centers that have. Many treatment centers that have never done telehealth are doing it now. As a result of that, they are finding ways to reach people that they couldn’t reach before. Even in regular times, it has been challenging for some of our treatment court programs and recovery centers to connect with the people who need them because they are so spread out. Just getting to court, and having to get to treatment, and they have a job somewhere hopefully – it’s been really a struggle. Many drug treatment programs are seeing now that they can continue some of this so that a person who has a job can attend the virtual court hearing on their break and then get back to work. They don’t have to find a way to travel across the town or the state to get to services. I believe that by necessity the justice system, supervision offices, treatment centers, recovery peer support groups, have all been forced to go virtual and make that lasting. Peer support groups like Smart Recovery have always been largely online and so they were in much better shape. AA and NA, where most people get their peer support from, had some virtual meetings and phone meetings, but many of those fellowships have stepped it up so people can see each other. I believe these additions are lasting. They are enormously helpful for access and for people who really want and need to wrap around themselves a support network that is available almost any time. I believe that’s going to happen and is a really positive outcome of everything we’re going through right now.

Brian, here’s what I want to see happen one day and perhaps be a part of: I want to focus on two impoverished communities – one in a large urban center, and one in a rural area. Using a cross-systems approach, I want to focus on the people who live there, who have hopes and dreams like everyone else and where addiction is alive and well (because addiction is everywhere), and help to create recovery-supportive communities in an intentional way. Leveraging and building resources in those communities. Part of that effort to create a recovery-oriented community would mean ensuring that people’s basic survival needs are met (needs for shelter, sustenance, safety, and sustainable healthcare). That’s a part of a recovery-oriented community. Because if people’s basic survival needs are not met, it’s very difficult to focus on sobriety and other elements of wellness. Understandably! And as we work on that, we develop or build upon those kinds of services and programs and connections that can help people move from addiction, to remission, to recovery. That means embedding in those communities really good evidence-based treatment and various treatment interventions, including medications to help support recovery. It means recovery centers, and recovery barber shops and salons, and gyms focused and designed for people in recovery – recovery high schools. That’s what I want to see. Let’s start small and be deliberate and intentional in growing it. That’s what I would like to see happen one day soon.

This interview was conducted on 10/07/2020