I was recently on a panel about the future of the field for an APNC event and thought a couple of questions and the notes I prepared might be worth sharing in a post.

What and how has the COVID-19 pandemic shown us about the importance of a multi-year perspective with individuals and inclusion of recovery management services, rather than medicalized care merely focused on initial disease management and symptom suppression?

A couple of things come to mind as a preface to my thoughts about this.

First, a quote from Robert DuPont, “The most striking thing about substance abuse treatment is the mismatch between the duration of treatment and the duration of the illness.”

Second, the conceptualization of addiction as a chronic disease with bio-psycho-social-spiritual dimensions. A recovery plan should address each of these dimensions if we expect it to be successful.

Biological medical models tend to emphasize the role of the medical provider, often at the expense of the agency of the patient. Often, the role of the patient is passive — a good patient is one that lets the doctor and their medications or procedures heal them.

The pandemic has been a psycho-social-spiritual crisis for many of us. And, with all we’ve learned about the effects of chronic stress, we know that biology can’t be isolated from psychology, spirituality, and the social context.

Successful management of chronic diseases typically requires behavior changes that are sustained over time to manage symptoms and prevent relapse. This is much more complex than it might first seem

- These behavioral strategies often include things like changes in eating habits, physical activity, sleep habits, and stress management.

- In many cases, these behavioral strategies involve changing habits that are practiced daily, often multiple times a day, for years and decades.

- These habits are often deeply enmeshed in the patient’s psychology, spirituality, and social context.

- The behavioral strategies involve extinguishing some habits and establishing others

What do we know about maintaining these changes over the lifespan, for years and decades? Unfortunately, very little.

It would be very helpful to know how the trajectory of chronic disease management is affected by important events over the lifespan. For example, how do life events like dating, marriage, divorce, geographic moves, new jobs/careers, job terminations, having children, loss of family members, natural disasters, health crises, retirement, etc affect the course of the patient’s illness/recovery?

Several years back, I looked for research on weight loss and diabetes management over the lifespan and found very little that was helpful.

All of this is to say that understanding the impact of the pandemic on people with SUDs will require:

- a lot of attention to matters that are typically considered outside of the scope of medicine; and

- for us to be present in the lives of people engaged in management of their recovery. We can’t know if we’re not there.

Finally, I’d add that, while we know too little about the long-term multi-dimensional dynamics of recovery management, there are important ways in which addiction treatment has been ahead of the curve. Many of the interventions we’ve been doing for decades aligns well with emerging concepts like social determinants of health.

Many of these interventions extend the duration of recovery support and monitoring, but we need to go further.

What do you see as the next phase of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement? Has the shift to a medical model of addiction helped or hindered this movement’s growth?

- Next phase? I don’t know.

- As the opioid crisis emerged and accelerated year after year, advocacy focused on access to medication, agonists in particular.

- This brought in a lot of medical and harm reduction advocates, and shifted the focus, goals, and values of recovery advocacy.

- The medical advocates often focused narrowly on medication and challenged its framing as a tool to assist treatment and recovery, often framing it simply as treatment and/or recovery.

- Harm reductionists brought in not just a toolkit of interventions like needle exchange and naloxone distribution, but also a philosophy of practice.

- This philosophy often adopts a neutral stance toward drug use, including addictive drug use.

- This neutral stance toward drug use in the context of addiction is complicated for people in recovery.

- Preventing harm, particularly death and chronic disease are unambiguously good.

- And, people in recovery view their addictive drug use as a symptom of a life-threatening illness with severe bio-psycho-social-spiritual consequences.

- A neutral stance toward AOD use by people with addiction is generally incompatible with their experience.

- The scope of advocacy has expanded from advocacy on behalf of people in recovery, to people in active addiction who we want to see get into recovery, and then to people who use drugs.

- All of these advocacy activities often get lumped together into “recovery advocacy.”

- There’s a Venn diagram in there, with significant overlap, but advocacy for people who use drugs and people in recovery are also going to diverge in important areas.

- Both are important, but they are not the same thing.

- I think sorting this out is an important task in the coming years.

- There’s a lot to overcome. For example:

- Most people in recovery from addiction will describe it as an experience of loss of control or impaired control–a loss of agency to the illness, the addicted self. Many advocates focused on people who use drugs reject the notion of a true-self and an addicted-self.

- People in recovery see recovery and change at the individual level as a critical outcomes while other advocates see focusing on individual behavior as blaming the victims for social/cultural failures.

- The lowest hanging fruit might be developing better ways to differentiate addiction from other drug use, and tailor approaches to the type of use. (Maybe recovery-oriented harm reduction?)

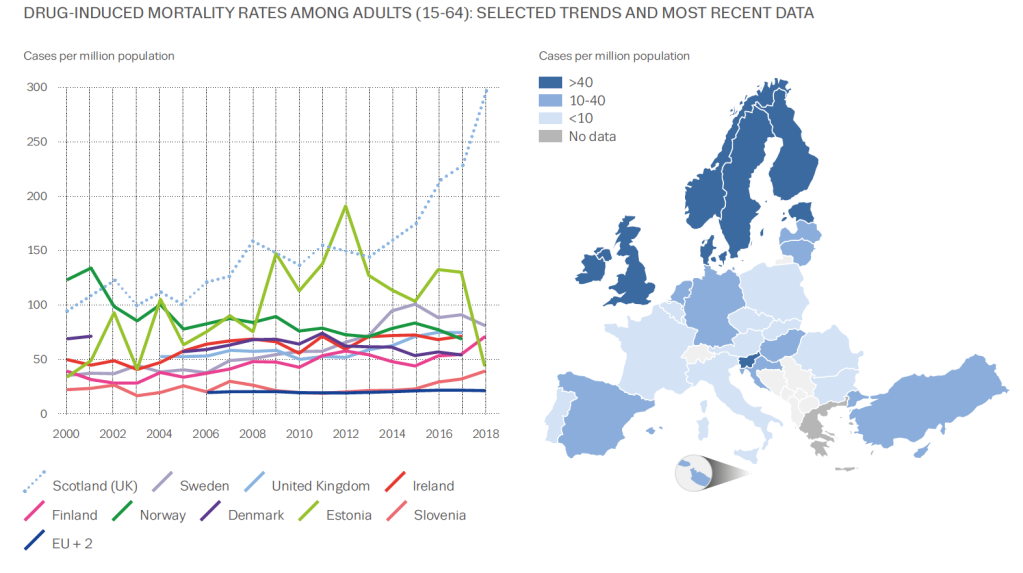

Graphic from European Drug Report 2020: Trends and Developments

Graphic from European Drug Report 2020: Trends and Developments

It’s not often graphs elicit an emotional response, but this one did for me. It’s from the EMCDDA’s recent report on drugs in Europe. The map shows that the UK has high levels of drug-induced mortality compared to most of Europe. But look at the dotted blue line on the graph. That’s Scotland. Worst in Europe and possibly the world.

It’s not a new phenomenon, our high drug-related deaths. The Scottish Drugs Forum makes the point: ‘Drug overdose deaths are preventable. We know how to prevent these deaths and yet they still happen.’

Kindness Compassion and Hope

So what’s being done about it? One of the highest-hit cities is Dundee. A commission set up to look at drug-related deaths took evidence from over 1000 people and made recommendations which included changing the system and culture, having holistic and integrated care and addressing the root causes of drug problems. The report title was Kindness, Compassion and Hope, which feels inspiring.

The Scottish Government has invested in treatment services with a particular emphasis on reaching more at-risk people and retaining them in treatment. Last summer it set up the Drugs Death Task Force, a group chaired by Dr Catriona Mathieson which has highlighted the need for wide distribution of naloxone, an immediate response pathway on non-fatal overdoses, medication assisted treatment (MAT), the targeting of those most at risk, public health surveillance and provision of equity of support for those in the criminal justice system. The Scottish Government has put £1M into research and £4M towards the task force’s six recommendations.

Standards for MAT have been developed, the country has a three week target from referral to treatment, ready access to prescribing, treatment free at the point of delivery, routine overdose prevention training, widespread naloxone distribution, generally accessible injecting equipment provision, low threshold clinics in many places and a high public awareness of the problem. In addition, there is investment in research which looks to find solutions to the problem. But is it enough? – the causes of our drug deaths are complex and rooted in poverty, exclusion, trauma and hopelessness.

A public health emergency

“What we are facing in Scotland is a public health emergency,” Joe Fitzpatrick, Scotland’s Public Health minister stated recently. “I am prepared to consider any course of action that is evidence based to save lives, whether its controversial or unpopular.”

Too controversial for the UK government are drug consumption rooms which Glasgow in particular wants to trial. Drugs policy is not devolved to the Scottish Government and Westminster won’t consider changing the law to allow this to happen, though one crusader is flouting the rules to deliver this currently.

One area in Scotland where consensus is growing is around the likely benefits of shifting to a public health approach. A cross-party parliamentary group, The Scottish Affairs Committee, held an enquiry into the subject and reported at the end of last year. It asked the UK government to declare a public health emergency making the point that the criminal justice approach has failed. It highlighted how current legislation on drugs stands in the way of tackling the issue from a public health slant.

And the UK government’s response? Pete Wishart, the group’s chair described this as ‘the almost wholesale rejection of recommendations.’ The Guardian has suggested this rejection of what multiple experts think is best for Scotland can only fuel calls for independence. When you consider that the UK government hosted a summit in Glasgow last February without consulting the Scottish Government or asking people with lived experience to attend, you begin to grasp the depth of the gulf that separates the two approaches.

The role of visible recovery

I wonder in all of this what the role is for recovering people, recovery communities and the powerful protective effects of developing strong social networks for those most at risk. What if we studied whether developing new social networks had a significant effect on Scottish drug deaths? What if we developed drug consumption rooms which were strongly recovery-orientated with visible recovery present? I suspect, that at the very least, this would boost hope. Hope is often in short supply in addiction, and anything that augments it is welcome.

Perhaps if every outreach service, every injecting equipment outlet and every treatment setting had people with lived experience prioritising the connection of those at most risk not just into treatment but also into a variety of supportive recovery-oriented settings, there could be a positive impact on drug deaths. Perhaps this would help people begin a cultural journey, moving from the culture of addiction to a culture of recovery as Bill White sets out. Not the only thing to be done certainly, our approaches need to be multiple, but something that doesn’t require the permission of the UK Government and which may augment the other interventions.

The Drug Deaths statistics for Scotland for 2019 have been delayed due to COVID, but will be published soon. I’d like to see that dotted blue line on the graph reducing, but that is by no means certain and much remains to be done.

The True, The Good, and the Beautiful

In his lecture titled, “The True, The Good, and The Beautiful” Roger Scruton asks what these three things embrace and what they have to do with each other. Overall, the subject matter of that lecture is aesthetics: the philosophy of art and beauty.

Scruton states that pleasure says, “Come again” and knowledge says “Thanks”. And therein lies a problem. How so? He elaborates that some experiences that are pleasurable are harmful, and that putting aesthetic values first in a hierarchy of values is a kind of “immoralizing”.

He asks what we learn from art, and if what we learn from art is a kind of truth not available from any other human activity.

He states by extension, in life, one may live a moralizing existence or find moral qualities within the experience of living. Is it even possible to not?

Ugly Truths?

In his blog post concerning children living with an addicted parent during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, William White wrestles with the topic of that truth, the bad side of that experience, and its ugliness.

(Incidentally, for many years one of my fantasy projects for our field has been that researchers would meet with large numbers of those with the lived experience of being raised with and by an addicted parent, and meet with other family members – to obtain information about what addiction illness consists of, and what recovery could hopefully look like. After all, only asking the one with the addiction illness is an information retrieval endeavor problematized by various features of the illness.)

Further, some involved in thinking about addiction, addiction treatment, and addiction recovery, have touched on or struggled with the possible inclusion or exclusion of a moral dimension in their considerations.

Anesthetic and Feeling

Interestingly, Scruton notes the word “anesthetic” contains the root word for “feeling”. That is interesting to me because many substances diminish naturally occurring feelings and diminish subjective experiences. And this causes me to wonder if either the philosophy of aesthetics or study of anesthetic functions can serve as a window into the moral dimension of addiction disease and its progression. As an example of that line of inquiry, I have spent a number of years studying the research literature concerning the simple harms that result from simple use.

Within that study, the information I have found most fascinating describes acetaminophen reducing both pain and pleasure, with unexpected effects:

- Diminishing the pain of decision making, reducing the positive value of feeling pain while weighing possible options (DeWall, C. N., Chester, D. S., et al 2015)

- Diminishing social pain, such as pain felt when socially excluded (DeWall, C. N., MacDonald, G.M., et al 2010)

- Reduced meaning threats, such as discomfort in considering existential meaning (Randles,,D., Heine, S. J., et al 2013)

- Diminished psychic pleasure and pain (Durso, G. R. O., Luttrell, A., et al 2015).

Acetaminophen dampens neuronal activity and thus both pain and pleasure. And as these researchers show, acetaminophen dampens the neuronal activity underlying pain and pleasure, not just the feeling of pain.

I also find it interesting that naltrexone produces anhedonia to music (Mallik, A, et. al., 2017).

Substance use, then, can be viewed as simply as access to various indigenous forms of anesthesia, like acetaminophen. What can be said of the functional life impacts resulting from the blocking of pleasure and pain by use of alcohol, opioids, cannabinoids, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, and cigarettes? For example, what does life look like aesthetically for the user? And what does life look like aesthetically for the witness? As Scruton states, there is the kind of art that is like sadness in a frame, or the kind of art that produces the kind of sadness that hurts you.

Factual Information vs. The Purpose of Art

In describing the value of the philosophy of art and the study of aesthetics, Scruton differentiates the mere instrumentality of factual information and the kind of thinking and judging that is done for someone on the one hand, from the purpose of art on the other hand. And within art he differentiates art that is blatantly moralizing from moral qualities that might be present within art.

Scruton states one does not go to art for factual information as the primary aim, but one goes to art for the experience. He extends that notion by stating not all truth is at the level of factual information, but that in some experiences of life, or of art, we may find a different kind of truth in the form of trust, support, or genuine spirit. “From the heart, to the heart”, as he says. He goes further and applies this to the emotional dimension. He defines “false emotion” as when the “I” eclipses the “you” – deriving from a certain kind of self-involvement that is harmful to others.

Thus, the aesthetic aim of the artist and aesthetic experience of the one experiencing the art may be similar or differ, but they will connect regardless – for better or worse, pleasurably or painfully, authentically or insincerely. After all, as Scruton explains, arguments about taste differences in aesthetic judgment “concern the matters of the soul”. And art puts us in a position of rendering our own judgment, not just receiving facts or judgments others make for us.

Does Addiction Have A Moral Dimension?

Scruton states that in matters of philosophy the greatest value is often in the clarity of asking a certain question and in carrying certain questions, but that often no further clarity is obtained in answering them. Is the possible inclusion or exclusion of a moral dimension in matters of understanding addiction, addiction treatment, and addiction recovery a question best asked and not answered, or a question that is best answered rather than only asked?

He gives us a hint toward a solution of that puzzle.

Scruton differentiates the kind of “truth” that is merely straightforward and literal, from the kind that is personal, subjective, and rescued from mere functionality or sentimental pretense. I apply that from two perspectives and for me they are not in tension:

- From the standpoint of mere information and sheer facts of a medical-scientific perspective, addiction disease and progression are not a moral matter per se.

- Concerning the aesthetic dimension of lived experience, to tell a child or adult child to eliminate or diminish the moral dimension would perhaps seem immoral or amoral, hurt or seem hollow, or simply seem silly and wrong.

Back to The True, The Good, and the Beautiful

Which leaves us with the topic of addiction recovery. If recovery is true, good, and beautiful, is it not a moral endeavor? Many children and adult children know that it is.

References

DeWall, C. N., Chester, D. S. & White, D. S. (2015). Can Acetaminophen Reduce the Pain of Decision-Making? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 56:117–120.

DeWall, C. N., MacDonald, G. M., Webster, G. D., Masten, C. L., Baumeister, R. F., Powell, C., Combs, D., Schurtz, D. R., Stillman, T. F., Tice, D. M. & Eisenberger, N. I. (2010). Acetaminophen Reduces Social Pain: Behavioral and neural evidence. Psychological Science. 21(7):931-937. DOI: 10.1177/0956797610374741

Durso, G. R. O., Luttrell, A. & Way, B. M. (2015). Over-the-Counter Relief From Pains and Pleasures Alike: Acetaminophen blunts evaluation sensitivity to both negative and positive stimuli. Psychological Science. 26(6):750–758. doi:10.1177/0956797615570366.

Mallik, A., Chanda, M. L. & Levitin, D. J. (2017). Anhedonia to Music and Mu-Opioids: Evidence from the administration of naltrexone. Scientific Reports. 7, 41952; doi: 10.1038/srep41952.

Randles, D., Heine, S. J. & Santos, N. (2013). The Common Pain of Surrealism and Death: Acetaminophen reduces compensatory affirmation following meaning threats. Psychological Science. 24(6) 966 –973.

Suggested Reading

Solomon, R. L. (1980). The Opponent-Process Theory of Acquired Motivation: The Costs of Pleasure and the Benefits of Pain. American Psychologist. 35(8), 691-712. doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.35.8.691

WHAT: National Institutes of Health and other federal leaders outlined their vision for a groundbreaking study that will aim to address gaps in reaching communities most heavily affected by the opioid epidemic with proven, evidence-based interventions for opioid use disorder (OUD). This approach is detailed in a paper published in a special issue of Drug and Alcohol Dependence, and also describes the early impact of COVID-19 on its goals, and the potential for uncovering insights at the intersection of COVID-19 and the opioid epidemic.

An estimated 1.6 million people had OUD in 2019; of these, only 18.1% received medication treatment for opioid misuse. To address this gap, in May 2019, the NIH announced plans to invest more than $350 million to support the multi-year HEALing Communities Study, a multi-site research study that will test the impact of an integrated set of evidence-based practices on reducing opioid-related overdose deaths by 40% in three years in communities hard-hit by the opioid crisis.

The largest study of its kind, the HEALing Communities Study is funded by the NIH Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM Initiative, or NIH HEAL InitiativeSM, a bold trans-agency effort to speed scientific solutions to stem the national opioid crisis. The HEALing Communities Study is administered in partnership by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of NIH, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The HEALing Communities Study findings will establish best practices tailored to the needs of local communities for increasing the number of people receiving medication to treat OUD, preventing opioid overdose deaths, and reducing high-risk opioid prescribing, creating a model to curb the nation’s opioid crisis.

The HEALing Communities Study is testing the impact of a community-based, data-driven approach in 67 communities across four states to facilitate the implementation of evidence-based practices in a variety of settings, such as primary care clinics, hospital emergency departments, community health centers, addiction treatment centers, and correctional institutions. An integral feature of the study’s design is to test the impact of engaging state and local governments, as well as community groups such as police departments, faith-based organizations, and schools.

Study research sites include the University of Kentucky, Lexington; Boston Medical Center; Columbia University, New York City; and Ohio State University, Columbus. The study will track communities as they work to increase the number of individuals receiving medication-based treatment for OUD, increase treatment retention beyond six months, provide recovery support services, expand the distribution of naloxone, a medication to reverse opioid overdose, and reduce high-risk opioid prescribing.

State and national (PDF, 786KB) reports indicate a concerning rise in opioid overdoses and deaths since the onset of COVID-19. The HEALing Communities Study provides a unique opportunity to understand the consequences of the intersection of COVID-19 and opioid epidemic in rural and urban communities.

Article

WHO: Nora D. Volkow, M.D., Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, is available for comment.

To learn more, go to: HEALing Communities Study.

Read the NIH Research Spotlights on the HEALing Communities Study: HEALing Communities Across America and Voices from the HEALing Communities Study.

For more information, contact the NIDA press office at media@nida.nih.gov or 301-443-6245. Follow NIDA on Twitter and Facebook.

NIDA Press Office

301-443-6245

media@nida.nih.gov

About the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA): NIDA is a component of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIDA supports most of the world’s research on the health aspects of drug use and addiction. The Institute carries out a large variety of programs to inform policy, improve practice, and advance addiction science. For more information about NIDA and its programs, visit www.drugabuse.gov.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health®

Stigma is commanded by a deep irony: where peer pressure is what likely keeps us quiet, peer support is what enables us to speak up.

Paul E Terry

One of the ways to counter stigma is for people with lived experience of addiction and recovery to share their stories. Indeed, Pat Corrigan, a respected stigma researcher, says that of the three approaches to tackling stigma – protest, education and contact – it is contact between members of stigmatised groups and ‘normal’ people that can increase understanding and dispel myths.

Mutual aid groups offer forums where this can happen. Sadly, there is also evidence of prejudice towards such groups. In Jonathan Avery’s book, The Stigma of Addiction: An Essential Guide, which has plenty to recommend it, there is, ironically, one toe-curling section about mutual aid groups where it seems myths are not dispelled but reinforced.

Avery argues that 12-step mutual aid groups ‘perpetuate the stigma associated with’ addiction. He argues that they do this by having features which ‘run counter to a science-based understanding of the disease of addiction’. These features are:

- Peer-based care

- Complete abstinence

- A paramount goal of anonymity.

He argues against these features saying:

- Best practice for addiction care calls for treatment to be delivered by a qualified health care professional

- 12-step groups generally frown on medication; they hold abstinence up ‘as a primary goal of treatment’

- And he says that anonymity gives the impression that being in a mutual support programme is embarrassing or shameful.

Where to begin?

It’s a challenge to know where to begin with this. Ignoring the fact that, according to Kurtz, AA members had a large role in spreading and popularising the disease concept of addiction, it’s an almost laughable irony that mutual aid groups get stigmatised in a book tackling stigma in addictions. Addiction stigma is bad enough, but recovery stigma? So, what’s the deal?

Firstly, mutual aid is not treatment, nor does it set treatment goals. The clue is in the title, it’s peer to peer aid or support. It is however true that 12-step facilitation (TSF) is a structured intervention used in treatment settings that is designed to encourage uptake of community-based mutual aid groups.

As it happens and while we’re on the theme of irony, getting people to engage with AA via an intervention like 12-step facilitation has been found to be as effective, if not more effective than accepted treatment interventions like motivational enhancement therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy. So, the idea that helping people into recovery should sit entirely in the domain of the expert is not only anachronistic, paternalistic and condescending; it’s wrong. Members of mutual aid groups may not be experts on addiction treatment per se, but they are experts in community recovery.

On medication

Secondly, AA’s stance (on which they sought advice from doctors) on medication is clear – it’s wrong to deprive anyone of medication that can help, although AA rightly highlights risks of cross addiction with some medications. It’s fair to say that, as in any diverse group, individual members will have their own opinions which could differ from AA’s and be harmful, but the organisation does not condone this.

For NA, I think it’s a bit more complex. I see it as an organisation for those seeking abstinent recovery – who don’t want to be dependent on either illicit or prescribed drugs, and there is a legitimate debate to be had about the role of MAT, but nevertheless, NA literature states: “the choice to take prescribed medication is a personal decision between a member, his or her sponsor, physician, and a higher power. It is a decision many members struggle through. It is not an issue for groups to enforce.” Hardly frowning on medication.

On anonymity

Thirdly, while the 12-step emphasis on anonymity grew in part out of the shame and social stigmatisation associated with alcohol dependence at the time AA was set up, this was only part of the story. It was felt that people would not be likely to attend meetings where there was not the safety of remaining anonymous. That was a pragmatic approach back in the middle of the last century and it many will feel its validity stands today.

It’s not only about this though. We expect our doctors to keep our anonymity and confidentiality secure, not because we are ashamed of our health issues, but because it is an important principle that it should be up to us what we say about our medical history.

According to AA literature, the organisation had another reason to promote anonymity. They wanted to keep all members on the same level – they aimed to maintain anonymity in the media, to avoid a cult of personality and have a goal of maintaining a degree of personal humility.

Deep irony

However, this approach does not mean members cannot share about their recovery. As AnneMarie Ward, CEO of FAVOR UK says: “I’m an advocate because I know anonymity doesn’t mean invisibility’. Indeed, many people who do go public are members of mutual aid groups. Around the world, recovery communities are actively tackling stigma by being visible and sharing their stories.

Mutual aid groups and their members are not perfect and there are legitimate debates to be had around legitimate criticisms, but the weight of evidence for good vastly outweighs the sort of accusations Avery levels against them, even if these assertions were robust. However, the accusations are not robust, they reinforce myths about mutual aid groups and risk stigmatising them.

Now to find this in a book about addiction stigma – that’s what I call a deep irony…

Who are you?

That is a loaded question!

My name is Kristal Reyes, and I am a person in long-term recovery.

I am also a wife, I’m a mother, I’m the Director of Crisis Services for Neighborhood Services Organization [NSO] in Detroit. I’m also the Clinical Director for First Step Referral Services, and I’m a lecturer for the University of Michigan-Dearborn.

Tell us a little bit more about what you do professionally.

I work within the realm of severe and persistent mental illness and behavioral health, more specifically substance abuse. With NSO, my work there is to do assessments and to get people into the proper level of care. So, if you are suffering with a severe, persistent mental illness, then I wanna get you into the right level of care for treatment. If you come to me in my private practice and you are suffering with some form of alcohol or drug abuse or dependency. I also wanna get you into the right level of care.

Okay, so I work primarily in Wayne County in Washtenaw County. In Washtenaw, I provide services for folks that suffer with severe and persistent mental illness as well as those folks that have drug addiction or abuse.

In the city of Detroit, I serve the most vulnerable population. I serve the folks who come into the emergency room, most of my patients are actively psychotic, and my job is to send a team in to do a bedside assessment and try to get them in the least restrictive care possible and to get them to the best care that they can get.

You mentioned that you’re a person in long-term recovery, do you have any other personal interest in addiction and recovery that you like to share?

So, you know, it’s so funny you asked me that… I was talking to my 11-year-old son the other day and, ironically, we were talking about death. I told them that I wanted to be cremated, and he asked me, where did I want my ashes sprinkled? I told them I wanted them sprinkled at Dawn Farm, and he thought that that was so odd. I explained to him that prior to August 30th, 2011, I didn’t have a life worth living, and so being a person in long-term recovery for me is the greatest gift that I’ve ever had, it was like my second birth. My recovery day is more important to me than my birthday. It was the day that I had the opportunity to become a mother… I was already a mother, but I was allowed to become a mother to my children. Recovery has allowed me to get married, to have children, and to help other people just like myself.

Tell us a little bit more about your professional experience in the area of addiction and recovery.

So I got my undergrad at Eastern Michigan University, I stayed there and got my graduate degree in social work with a concentration in mental illness and addiction. I started off and Dawn Farm. So you gotta know I went through the Farm in August of 2011, and literally the day that I reached that two year mark, where I could work, I began working at Spera, their detox. [Dawn Farm requires a waiting period of 2 years before hiring alumni.] And I’ll tell you, it was the best ever. I probably worked 40 to 60 hours a week. I worked so much they told me I needed to stop working. I worked there until I completed my master’s program. Dawn Farm has always had a special place in my heart [obviously! ] because I went through there. I still keep in contact with former Farmers, I still keep in contact with the team that works over there, I share clients with them on a regular basis.

Following Dawn Farm, I had a short stint with outpatient services at Hegira. I left there and came over to NSO where I started with the COPE team [Community Outreach for Psychiatric Emergencies]. From there, I went from working as a COPE clinician to the program manager, to the director, and now just recently, I am now director of our substance abuse programs that we are implementing, which is an evidence-based MAT [medication-assisted treatment] program.

Professionally, what are you most proud of?

I’ll have to say the work I do at First Step Referral Services. Lots of our clients come from the court, and having the ability to see someone walk in… and to see them walk out, as this kind of changed person is such a gift. I knew it from a personal level– what recovery can do–but watching some of these folks come in and the light bulb goes on. Being a person in recovery and working at Spera… I’ve seen some of the sickest people that you can see, right? But sometimes those people that are kinda in the middle, before they have to get to go into Spera… So, a first DUI or a minor in possession… I had a client come in the other day, and he tried to bullshit me with his using history. I pulled my mask down and I was like, “Dude! I’m with you. I’ve been there.” And, I told him that smoked weed I drank, and I was a felon. He was like, “What?”

What we had was that ability of one addict relating to another, but it was on a totally different level. You could tell that his guard went down, and he was able to share his experience with me.

I think that one of the biggest pieces of the work I do right now is from a few years back when I got the ACEs training. After that, I was able to put into perspective the adverse childhood experiences and actually find… not necessarily that reason… but being able to help somebody with the why. Why do I keep using? Why am I like this? Why am I an addict?

We’ve been getting a lot of calls from these young folks that are getting tickets for driving under the influence of marijuana and for them to come in here and for us to have an opportunity to share with them… not my position on weed or not my story of my marijuana abuse. But, to share with them like, “Hey, I understand why you smoke weed… this is what it does for you… this is why you smoke it. When you’re ready… when you’re willing to look at some of these things and find some different coping mechanisms, call me because I’m here to help. Then, when the phone rings a week, or two weeks, or a month later, and that same 21-year-old kid is like, “Hey man, maybe I don’t need to smoke weed.”

I think that that has been the most rewarding of all the accolades that I’ve had. It’s just kind of seeing the light bulb go off.

What keeps you working in addiction and recovery?

That’s part of it. But in all honesty, those four little boys that I have. I am the first person in my family that has been able to have children that don’t have to have parents that are using addicts. I can’t take back the trouble and the trauma that I caused my oldest son… being the child of an active addict. I cannot change that, I cannot fix that. But this year marked my ninth year clean, which was the exact timeframe that I was using. So for me, that was a huge gift. I get to be clean the same number of years that I used. So now, those three little boys that I had after him, never have to see me high.

So I get to help those mothers and fathers, those first generation people to have the understanding of recovery. When I got here, I had no idea that people live without drugs. NONE! I’ll never forget this, when I had my intake at treatment, he asked, “So what do you want?” I said, “I just wanna drink and smoke weed like everybody else without getting in trouble.” And he was like, “You know what kid? You belong here.”

I never ever had a goal of never using. I just wanted to feel human. I just wanted to work a regular job and stop getting arrested. I didn’t know that I could have a life worth living that didn’t include any mood or mind altering substances. For that, I’m so grateful, and I just wanna give that to everyone else. I just wanna offer it. I wanna wear recovery on my forehead. Like, “Hey! If you want this thing, you get to have it. It’s free. I’ll tell you all about it. It doesn’t cost anything.”

How has the pandemic affected your work?

So I think a pandemic has probably affected me personally more than professionally. I’ve seen a lot of people that I’ve been really close to that just simply couldn’t handle the pandemic, they couldn’t handle not going the meetings, they couldn’t handle the change that came. I’ve seen a lot of people go out with days, and weeks, and months, and years, and decades clean, and that’s been a really hard thing to handle.

The other piece to that is knowing that there’s no access to treatment. If you work in this field, and you know that when someone calls you when they want treatment, you’ve got about five minutes to get them in and to get them a bed. When the pandemic hit, things just stopped. Meetings stopped. Recovery stopped. Access to treatment stopped. For the first time in my entire professional and personal life, recovery as I knew it was on hold.

So that meant the newcomer didn’t have a safe place to go. No one was brewing coffee, and most importantly, Spera closed its doors. For that was traumatic in itself… where do these addicts go? What are they supposed to do?

So I left my phone on at night. I stay as close to work as possible. We found that a lot more people were calling us… they were just Googling trying to find somewhere to go. We got a lot of cost for methadone and Suboxone, and I don’t provide that here. So I spent a lot of time on the phone with sick and suffering addicts who were looking for help, and I just simply couldn’t provide it. for the first time, I didn’t have a number to give them.

As far as my work with NSO… I think that’s the part that hit us the hardest, because COPE shut down. We were no longer able to go into the hospitals to see our patients. And the other side to that is the folks that were in recovery with severe system mental illness… their lives changed, they were afraid. If you already suffer with schizophrenia or paranoia or anxiety… in the pandemic, that is tri-fold now. These folks were afraid to leave their homes.

I lost a really good co-worker of mine during the pandemic, not to COVID, but to untreated mental illness because he was afraid to leave his house. So he stopped reaching out, he stopped going to work, he stopped taking his medication because he ran out and his paranoia got the best of him. He committed suicide after 20 years in recovery with severe and persistent mental illness.

You’ve already spoken to this, but do you have any more to say about the effects of the pandemic on the people you serve?

I think one of the unintended consequences is the increase in [AOD] use, people are using more.

People that didn’t ordinarily use… or the people that were… I hate to use this term… but I’m gonna use it ’cause I can’t think of anything better… people that were functioning alcoholics… people that drink after work, but could get up and go to work every day, never had a DUI, folks that smoke weed at the end of their shift but got up and went to work every day and didn’t really have any hard consequences of their use… all of a sudden their job was gone. So those folks that would wait until 5:30 or 6 PM to drink, all of a study started drinking at noon. And, as you know, their body can develop dependence to alcohol without permission.

So we started seeing an increase in younger people coming in that were smoking more marijuana than they had before. On top of the fact that they had been working, but now you have an increase in unemployment benefits. They’re already living check-to-check, but now they’re getting on employment benefits, they have no requirements as far as getting up and going to work, so they’re starting to drink earlier in the day and drinking later on in the evening.

The other piece that I think really got a hold of me are the children. I don’t think that people really understand and that a lot of the families that we service have kids at home, and those kids to look for their parents to go to work and keep stable. Those kids look forward to going to school every day. Without school, parents are now more stressed out, they’re home with their children, they’re using, they’re smoking and drinking at home now on a much higher level than they were before. Kids aren’t in schools where they’re staying up later. The unintended consequences of seeing their parents drinking and smoking more often. And now that school’s online, we’re seeing the same thing. You’re seeing parents that are like, “it’s legal to smoke weed.” So, they’re smoking weed and the kids “classrooms.” Before, at least kids would be able to get that eight hours a day away from their traumatic homes, and away from their parents were smoking and drinking at home, to go to this place where they felt safe and secure, and now they don’t have that.

So you have stressed out parents who already have risk factors, that are now increasing their use, and these kids that are stuck at home since March of last year without any outlet at all, without any safe space. It seems like these kids are on this heightened sense of awareness… they’re on a 10… an emotional level of a ten, consistently. From our work in crisis, we know that that’s not good for their brains, it’s not good for their living, it’s not good for their sleeping, and it’s also a predisposition to them using drugs and alcohol at an earlier age. I’m really concerned about the long-term effects of this pandemic on these youth… their life has just been completely disrupted.

What, if any, long-term effects do you anticipate for the field?

Well… in 2018, when I got a promotion at NSO, I sat at a table and I discovered that clinically, I was good at what I did with individuals and small groups, but I started to learn that I needed a different piece to this puzzle in order to be as effective as I really wanted to be.

So I went back to school and I will graduate with a Masters of Public Health in December from Purdue. What that education has taught me is a population view, so I think one of the long-term effects that we’ll see on this is the effect that it’s having on the kids.

I think that that’s going to have a huge impact–the effect that it’s having on the youth… the youth that didn’t have access to high-speed internet at home, the youth that were not able to go to school to kinda get that reprieve, the youth whose ACEs [Adverse Childhood Experiences] scores just jumped from a 4 to 7 over the term of this pandemic. That’s gonna be, I think, the biggest consequence, at least in my field right now.

The other piece to that, I think, is going to be once things loosen up a little bit, because the pandemic is one thing, but there’s a whole other health crisis out here that we’re fighting along with the pandemic, and that’s the systemic racism. Because of this, you’ve got this inequality as far as getting into treatment and having access to beds. I think we’re just gonna see that multiply.

We see that here. I see clients right now that I don’t charge because the Ypsilanti Transit Center has decided to transition some of their routes, and so some of these people who could normally go to another treatment provider under their Medicaid coverage can’t get it. Or, because of COVID, they can’t get there with their children… it’s an hour and a half bus ride or there’s no bus ride at all. So they come to us because we’re right in their neighborhood. So I take them in, and provide treatment, and give them resources to the best of our ability. I think we’re already seeing some of those effects, and those effects are just going to increase.

Do you see any new opportunities in the pandemic?

Absolutely. One of the best things that’s happened in the pandemic is the increase in telehealth. Telehealth was one of the most underutilized interventions known. You had to have really great insurance for it to be covered and even then, it was touch and go.

One of the benefits that I think I had in my private practice was the fact that because we were so small, it was easy to change, like there was no red tape, there was no bureaucracy. It was like, “Hey, we gotta do this. This is what we’re gonna do.” Now, my husband is taking a little longer to transition over. [laughter] He was really skeptical. But for me, it was like, we just need to do this now.

So, there was not really a time that we had a lapse in treatment for folks. But that was for us. For these larger entities, this is a huge undertaking to offer complete telehealth under the HIPAA guidelines. For us, it was just super simple, refer these larger entities, not so much. One of the things that we’ve seen with our outpatient groups is the difficulty in keeping folks connected, so to speak.

So before you’re coming in… if you know anything about addiction, that the number one treatment modality for addiction is connection, right? We know that upfront, whether it’s connection in AA or NA, or connection in treatment, it’s connection. Connection with other addicts in recovery. So, when you take that platform away and you put it all on the screen… I don’t know about you all, but there’s been a myriad of meetings that I’m in that I’m supposed to be paying attention and I’m doing 10 other things. So we find in outpatient that it is a little bit harder to keep people engaged than it was when everything was in person.

So I think that taking that extra step and making those phone calls and connecting with people that way. I run a woman’s group for trauma survivors, and I find that we’ve been text messaging. That was under-utilized on my end. So, being able to meet with them on Zoom and then text messaging them here and there, or allowing them to text message me if necessary, has been super helpful.

For sure, Telehealth. Let me just say this, we talk as social workers a lot about meeting people where they are, but not leaving them there. This pandemic has allowed us to literally do it. I’m literally gonna meet you in your living room, right now! If you want treatment, here I am, I’m gonna meet you in your living room with your scarf on, your doo-rag on, your kids running around the background. If you tell me that you want services and you tell me that you want treatment, I’m gonna give it to you right in your living room you don’t have to leave. I find that when I tell people that… when folks coming here that have been sent by the court, or they just walking in, I can say, “I can meet you where ever you’re at. I can meet you in your living room. Send me your email address, and I’m gonna literally meet you in your living room.” And they say, “I don’t have a laptop.” I say, “Do you have a phone? So here we go.”

So I think that that this was definitely underutilized. I’m so helpful that when the pandemic and the consequences of it begin to kind of lessen and die down, we will still have the opportunity to continue to use this platform. I think that we have the capability of reaching so many more people this way. Not everybody’s ready to walk out into the world, but if you can meet them and their living room… that’s a good start.

Last question, if you were able to devote yourself to a fantasy project to improve treatment and recovery support, what would it be?

I would like to say it’s a tough question, but it’s not… it’s really easy. For me, it would be universal health care. Because, if there was universal healthcare, if there was universal access, then there would be no wrong point of entry. Right now, I have to turn people away because I can’t take everyone for free. Right now, I have to do an assessment with someone and hope that they follow up with the recommendation that I’m giving them.

For people that don’t know, I got to Dawn Farm literally by the grace of God. I didn’t live in Washtenaw County. I hadn’t been to treatment before, they literally gave me a $10,000 bed.

I’d like to think that at this point, I’ve paid that $10,000 back by staying clean and giving back. So I try my best to take in as many clients as I can that don’t have the ability to pay. But, to be someone in recovery and to see that sick and suffering addict, to see that mom that needs help, and that I can’t give them help, when I have the resources, I got a door, I got a table, and I got a degree. But to not be able to service them simply because they can’t pay or because they don’t have the right insurance is really hard for me. So if I had it anyway, it would definitely be universal healthcare, because then it wouldn’t matter. Then, whatever door they came in… if they came in because they needed childcare, I could help them with their substance abuse. If they came in because they had a severe and persistent mental illness or they had depression, I could help them with their substance abuse. This way right now, there is so much red tape, it’s so hard to get treatment to the people that need it and want it the most.

I think the other project to go along with that would be… I’m a firm believer in the ACEs study… that these experiences… this trauma that we have as a society. I’m a firm believer that our alcohol and drug use and addiction are directly correlated to the life that we all have to live. So… I remember someone sharing with me, I wanna say it was William White, about plucking the tree out of the woods. You pluck this dying tree, and you stick it into this recovery area and it gets bold and beautiful, and then you take it out and you put it back in that same environment, it dies.

But what if we put recovery in the community?

So one of the goals that I have… my five-year plan… is a building down here… I don’t know how far that’s gonna go, and I’m gonna tell you a secret. There’s a building out here… down the role from us… near Eastern [Michigan University] that’s been empty for years. Every time Rhett and I drive by it, our goal is to purchase this building so that it can be like the epicenter of recovery… where no one that walks in that door is turned away. If you want services, you come in and we help you figure it out. Almost like the Ozone House [a local youth shelter and support program] is for kids, but this is for anyone that wants treatment… anyone that wants services.

So my ultimate goal is to open that building and have it open and brighten up the Ypsilanti community where I live, work, and play.

So the recovery is possible for anyone that wants it.

Juvenile Drug Treatment Courts: Your Questions Answered

Schedule your one-on-one video conference October 26 or 27

NADCP’s National Drug Court Institute Drug Court U is hosting virtual office hours to answer your questions on juvenile drug treatment courts! Schedule a one-on-one virtual appointment with Dr. Jacqueline van Wormer, NDCI’s director of juvenile training and technical assistance.

Whether you have an established juvenile drug treatment court program or are looking to start one, Dr. van Wormer can help!

Reserve your appointment now! Times are limited.

Just like office hours in college, Drug Court U offers treatment court practitioners the opportunity to schedule one-on-one discussion time with experts and receive individualized, confidential instruction via video chat or conference call.

About Dr. van Wormer

Jacqueline van Wormer is the director of juvenile training and technical assistance at NADCP. Before this appointment, she was an assistant professor at Whitworth University and Washington State University. She has held various positions in the criminal justice field, including serving as the Spokane regional criminal justice administrator and as the coordinator for both the adult and juvenile drug programs in Benton and Franklin counties.

Dr. van Wormer has trained and lectured extensively on issues related to treatment courts and pretrial reform. She has worked with hundreds of planning and operational therapeutic court teams to offer technical assistance, facilitation, and training. She has also written extensively on juvenile drug treatment courts, risk/need tool development, detention alternatives, effective treatment options for offenders, and collaboration among social service agencies. Dr. van Wormer received her Ph.D. in 2010 from Washington State University.

The post Juvenile Drug Treatment Courts: Your Questions Answered appeared first on NADCP.org.

Boo! How to Overcome the Fears of Sobriety

October is notorious for ghouls, goblins, and ghosts galore—all things that scare us and can make sleeping at night a daunting task. In terms of “spookiness,” Hollywood-esque images of creepy dolls and terrifying clowns may come to mind. When it comes to your recovery, you may be facing some fears and scary night-time images of your own.

If you’re new to recovery, this huge overhaul and journey that you’re embarking on is probably quite scary! Even if you have time in recovery, the day to day struggles can be equally as terrifying. The fear of returning to use, being the most obvious, can be all-consuming at times, but there are countless other anxieties associated specifically with early recovery.

Who will I hang out with? Where will I find new friends? Will people still like me when I am sober? How will I cope with stressful situations? What will I do to fill my free time? Will I ever have fun again? Whatever your fears may be, they’re valid, and can be addressed and managed in healthy ways.

How to Understand and Overcome the Fear of Being Sober

Address the fear of change

The root of many common anxieties is the discomfort that is associated with change. Humans are creatures of habit, and have evolved to elevate awareness and senses when change is present. These mechanisms occur to protect individuals—almost like the way in which you might sense someone walking behind you.

To overcome this, you can practice acceptance and turn your worries over to your higher power or the collective wisdom of a higher counsel such as your sponsor or an AA or NA group. By practicing acceptance, you can find peace in knowing that you are powerless over drugs and alcohol, they have no place in your life, and beginning your recovery and sobriety is exactly what you are supposed to be doing, or rather, what you must do to make your life manageable again.

Embrace the opportunities

During early recovery, you may lose old friends that you were actively using with. You may be unable to patron the same places you once spent time in to have “fun”, and your idea of “fun” and leisure time will completely change. That’s okay and can be a beautiful thing.

Your recovery network, if utilized properly, can give you access to many individuals from all walks of life who genuinely understand your ailments and your accomplishments in sobriety. Find a group of individuals that uplift you and make you feel good about your recovery. The people you surround yourself with and reach out to can be an incredible support to you during this journey and the opportunities for new friendships and new fun is limitless.

Step out of your own way

The shame and guilt associated with active use probably held you back more than it helped you move forward in your life. During your early recovery, it can be tempting to return to ways of thinking that can put yourself directly in the way of your own growth. Don’t get in your own way. Take a deep breath and remind yourself of the serenity prayer each day:

Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change

The courage to change the things I can

and the wisdom to know the difference, just for today.

When you find yourself blocking your own path—reach out to someone in your support network. Talk through the things you are facing or the worries you have with someone who has experience or can provide you with insight.

Your recovery has the potential to help you be a better friend, partner, sister or brother, professional, volunteer, and more. As long as you allow yourself to take the necessary steps forward, you can take this growing opportunity and newly found free-time to improve your life in all areas. You may find that to grow, you have to take inventory and release unhealthy habits from your past. That is expected, and a sponsor or close friend in your program is a great source of support for you in doing so.

Find yourself

During active use, excitement and joy in your life probably came predominantly from your drug of choice. It’s time now to find what makes you feel alive again, because that’s where your passions exist. This might be reading, painting, exercising, playing with your kids, or learning new things. You may have to try out a few new things before you find your “aha!” feeling. That’s okay too! Rediscovering your personality in sobriety can be scary—but it can equally be a beautiful and exciting thing. Utilize your journal as you try out new things to reflect on how the experiences made you feel. Once you find something that you enjoy, make special time for it and do it to the best of your ability.

Learn to laugh

Finally, even in moments of fear, learn to laugh whenever you can, as often as you can. When you find yourself in the midst of your own anxiety, it can be overwhelming and all-consuming. You may tell yourself that dwelling on the things you can’t control, obsessing over the fears and the unknown—that’s easier than addressing them and finding a reason to laugh or smile. That’s simply not the case. Focusing exclusively on the negatives of your recovery can lead to extreme mental and physical discomfort, and may eventually lead you back to the feelings that drove you to use substances in the first place.

Find reasons to laugh and smile through gratitude each hour of your day. Though your journey through recovery is absolutely serious, try not to always take yourself so seriously. On your hardest days, you might try writing down two or three reasons you had to smile. When you imagine your reservations and fears, remember that they are feelings. You cannot always control how you feel, or when you feel fear, but you don’t have to let the feelings or fear control you. You CAN do this.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, ‘like’ the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The SMART Recovery USA Board of Directors is pleased to announce the appointment of seven new members. In their ongoing effort to grow and diversify, this brings the total to seventeen members.

Board President, Bill Greer says,

Not since SMART was founded more than a quarter-century ago, have we assembled a more talented and dedicated group of people to help lead our organization. They have the diverse skills and vision we need to innovate our services and extend SMART’s reach to every individual and family who needs our help.

The need for SMART Recovery has never been greater as the COVID pandemic has made an already daunting addiction epidemic even worse. Our community will meet these challenges more quickly and more effectively with this infusion of new leadership.

Welcome To:

Bobbe Baggio, PhD

Bobbe Baggio, PhD, has been involved with SMART Recovery since 2011 and has worked with SMART to develop training solutions globally. She has been the Chairperson of the General Training Committee for SMART Recovery International since 2017.

Since 2002, Bobbe has been CEO of Advantage Learning Technologies, Inc. She has held academic positions as the Associate Dean of Graduate Programs and Online Learning, Adjunct Faculty, Associate Provost and Graduate Program Director of the MS program in Instructional Technology Management.

Bobbe is an author, public speaker, strategic advisor, educator in instructional technologies and learning, and a learning and talent development consultant for a global and virtually connected workforce. Her expertise draws upon her experience as a Fortune 100 IT manager, 20 years of consulting experience, and her doctoral studies in instructional design for online learning. She believes in designing training based on research in instructional principles and that technologies are here to help everyone and enhance human performance. Her most recent article is AI and the Agile Workforce, published in Workplace Solutions Magazine, 2nd Quarter Ed., 2019.

DeSean Duncan, BA, CPRAS, LADC

DeSean Duncan has been in the recovery field for seven years. In long-term recovery, he was a peer and then became an assistant director at a recovery center in Roxbury, Massachusetts. He has shared his story with the Boston Herald and has had many speaking engagements.

DeSean was honored to work with the addictions medicine consultation team at Rhode Island Hospital, where he was the only non-clinical team member. He has served on the opioid task force for Beth Israel Hospital and has worked on Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker’s opioid workshop.

With his passion for recovery and offering recovery to underserved populations, DeSean has launched SMART Recovery meetings in inner cities.

Barry Grant

Barry A. Grant is the Outpatient Programs and Services Director at Hope House Treatment Centers in Crownsville, Maryland. Over the past 20 years, he has shared his knowledge of addiction recovery and reentry strategies with others based upon empirical knowledge and the early developmental stages of SMART’s program for correctional facilities InsideOut®.

Barry is an international facilitator of self-empowerment through natural recovery. His work has been recognized by the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, along with U.S. and state Senators. His speaking engagements include the 2020 World Congress Opioid Management Summit and an introduction to SMART Recovery on Capitol Hill on behalf of the Secular Coalition of America.

Barry has previously served on the SMART Recovery Board of Directors and is a SMART facilitator/trainer and REBT in rehabilitation institutions, correctional facilities, and universities. He served as Program Manager with the New Jersey State Parole Board and the Parolee Aftercare Transitional Housing program.

Barry has a Master’s degree in Human Services, is a Maryland Board Approved Drug & Alcohol Supervisor, holding various certifications in addictions and chemical dependency counseling.

Dan Hostetler

Daniel Hostetler comes to us from the West Side of Chicago, where he directs Above and Beyond Family Recovery Center. This free outpatient behavioral harm-reduction addiction treatment center features SMART Recovery and SMART Family and Friends alongside six other self-help process groups.

Before this chapter in his life, Dan served as president of an international change management consulting firm and has resolved thousands of business dilemmas during his 24-year consulting career. With a master’s degree in Nonprofit Management, a Diplomate in Logotherapy (Viktor Frankl), a CADC, and a CODP I, Dan’s passion for lessening the impact of, up to and including the eradication of, harmful and unwanted addictions is unbounded.

David Koss, JD

David Koss, JD, earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor and his law degree from Georgetown University. He began his career as Legislative Director to a Michigan Congressman who served on the House Banking and Science & Technology Committees. In 1983-1984, he served on the staff of the Governor of Michigan in Lansing and Washington.

An attorney in private practice (and a member of the District of Columbia Bar), David has represented banks, investment companies, builders of affordable housing, and tenant advocates. His work has included securities filings, corporate mergers and acquisitions, and government affairs. More recently, serving as the SMART Recovery Director of Government Relations, he has educated numerous Congress members and their staff about SMART Recovery and our need to launch more meetings to help end the opioid and broader addiction epidemic.

David’s association with SMART Recovery began in 2015 when he became a meeting facilitator. He has served as Regional Coordinator for our Delaware-District of Columbia-Maryland region since 2017. David has led the growth of the SMART Recovery East Coast into a premier annual event bringing together participants, volunteers, professionals, addiction scientists, and public health officials.

David received the Joe Gerstein Award in 2019, recognizing his extensive volunteer work benefiting the SMART Recover community.

Ron Lott

Ron Lott majored in economics at the University of Houston after serving as a medic in the US Army. He spent the next 40 years as CEO of Lott Marketing, a sales and marketing agency in the foodservice industry. Ron has served on numerous boards of Fortune 500 food manufacturers, industry organizations, and private companies. After retiring in 2015, he began volunteering in the prison system for Bridges To Life. A year later, Ron found SMART Recovery and introduced our InsideOut® program to the Texas prison system, which has authorized this program’s use at all of its correction facilities. He co-authored, along with Charles True, Successful Life Skills, and has generously donated all proceeds from the book’s sales to SMART Recovery.

Ana Troncoso

Ana Troncoso attended Macalester College, where she majored in English and creative writing. Since then, she has gained 25 years of administrative and operational experience across the private and public sectors, and has maintained a strong focus on client service, policy development, and technology implementation.

Ana came to SMART Recovery in 2010, first as a participant and later as a volunteer, and has facilitated approximately 1,500 hours of SMART Recovery meetings. In 2011, she served a term as Arizona’s Regional Coordinator; more recently, she was named the greater Phoenix area’s Local Coordinator.

In 2012 Ana founded a small consulting practice, which shares REBT strategies with a broader audience, and in 2014 she became certified as an REBT coach. She also maintains a certification in Mental Health First Aid.

Ana’s pronouns are she/hers and ella/suya.

Click here to find the complete list of Board of Directors.

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

- Who are you?

I’m Chrissy Smith. I’m a licensed clinical social worker, and I’m a mom, and a wife, and that about sums it up. I have a Bachelor’s in Social Work from Bradley University with a minor in Psychology. I have a Master’s in Social Work with a focus on Community Behavioral Health from the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana.

- What do you do professionally?

I work for UnityPoint Health – Unity Place and I’m the manager of all substance use outpatient programs for UnityPlace. That includes specialty courts, and medication addiction treatments – opioid methadone program, buprenorphine clinics, and naltrexone. We also have a naloxone distribution grant that covers about 40 counties in the state of Illinois for drug prevention and overdose prevention. We have trained and distributed thousands of naloxone kits. It’s been a cool thing. We have some leave-behind programs with some jails and prisons and fire departments and police. It’s pretty cool. They’re doing some good stuff.

- Do you have any personal interest in addiction and recovery that you’d like to share?

I think if you would have asked me this question 17 years ago when I first got in the field I would have said, “No, I don’t think I have any kind of personal relationship with substance use. I just am drawn to it.” As I’ve kind of matured as an individual, and as a professional in the field, I think like many other people, of course I have personal experience with substance use and people who I love that have struggled with substance use. And people who I love that are caught up in the opioid epidemic, and that you would have never guess would have used opiates, but did. At this point in my life, yeah sure, I have people that I love and care about that struggle with addiction and are looking to figure out recovery. But I wouldn’t have probably said that when I first started.

- Tell us about your professional experience in the area of addiction and recovery.

So, I started in the area of addiction and recovery 17 years ago as a Bachelor’s-level intern at a women’s long-term addiction treatment facility. From there I did some outpatient programming, ran some groups, did some individual sessions and then worked my way into leadership of those programs, including justice programs as they apply to substance use, and some of our contracts around that. I did some private practice for a handful of years specializing in substance use. And then about 7 years ago I began my work with the opioid epidemic, and did primarily that until just recently when I took over all of the outpatient programming for UnityPlace. But my experience and my specialty for the last 10 or so years has been the opioid epidemic.

- What are you most proud of?

You know, what I think I’m most proud of, probably, is my work in the community around awareness and stigma. It’s been some of the most challenging work that I’ve done. When I took over a methadone program – there are a lot of people who have a lot of different beliefs about the use of medications for the treatment of addiction. And so, when the opioid epidemic happened, we got a lot of push-back and a lot of misunderstanding about what that was. And I think I’m most proud of all the community events I’ve attended, speeches I’ve given on awareness, challenges I’ve had discouraging the stigma around it with professionals and families. I get super passionate about being a voice for people who haven’t been heard. And so I think that’s the thing I’m probably most proud of.

- What keeps you working in addiction and recovery?

Until there is a day where people don’t need me to be a voice for them, then I still need to be working. Right? Because I think that there still needs to be advocates in this field and advocates for the people we serve, and people that can be a voice for addiction and recovery. And you know there’s nothing like seeing some of the change that happens in this field. It’s very rewarding. Not everybody says, when they go to work, they saved a life. But there are definitely days where I know for sure I went to work and because of that a life was saved. And that’s super rewarding. And not only that, but I feel obligated to the people that I love. We know that addiction and recovery can impact all kinds of people. And so, my family and my friends aren’t immune to that. And so by staying in the field I think that I am making an impact on my direct life as well as my community.

- How has the pandemic affected your work?

I think the number one thing is safety. We work for a program where working from home was not an option. Where a lot of people had the opportunity to shelter in place, and work from home, , we didn’t have that luxury, because methadone clinics run 365 days a year no matter what. A virus didn’t stop people’s need for treatment, right? So, we have been working full time and are sometimes very nervous and fearful about what that means for not only us but for the people we’re serving. Because when the pandemic first happened everyone was told to shelter in place. Well, that wasn’t really what we could do. So, we had to work really closely with UnityPoint Health and with our clients so we could do so safely. And what I found was that takes a lot more education than you would think, right? You and I probably watch the news and have a sense of what’s going on and in the nation, and what kinds of things we can do to keep ourselves safe. We’ll read articles to do that. It took a lot of education and still takes a lot of education with the people we’re serving just on how to keep them and ourselves safe. As a clinician I’ve had to learn how to practice with a mask on, and a face shield, and other protective barriers. You know, facial expressions and non-verbals are a thing that we cherish in our field. And when you can’t see someone’s facial expressions that’s a challenge. I think that’s probably the biggest thing.

- What effects of the pandemic are you observing in the people you serve?

You know, I think there’s probably been some good and bad. So you may or may not know this – that the DEA, when this all happened, in an effort to kind of minimize the amount of movement people had to do, the DEA and Federal government modified some of the guidelines that are in place for medication addiction treatment. And so that has been good for some people. So what we have found is that some people when given a little more freedom with their medication have actually done really well. They have learned to manage their medication. Sometimes the environment – the clinic – has been stressful during the pandemic, and so not having to come to that has given them the opportunity to keep themselves safe and shelter in place more. And so that’s been good. The flip side of that is some people are really struggling.

- What, if any, long term effects do you anticipate on the field?

We have seen increased rates of substance use through toxicology testing. According to data collected from our local coroner, our rates of overdose have increased again even with the amount of naloxone we have in this area and overdose prevention education. I think that people are experiencing repeated trauma dealing with this pandemic and all the stressors that come with it. So I think we’ll see an increased need in people to process all of that. According to an article written by SAMHSA titled “Intimate Partner Violence and Child Abuse Considerations During COVID19” there is an increase in violence and abuse. We know mental health symptoms and suicide are both things that have been increasing and those are all things that directly impact our field*.

* Czeisler MÉ , Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1049–1057.

- Have you seen any benefits or new opportunities in the pandemic?

I think it’s been a good opportunity for us to review some of those Federal guidelines in methadone, especially around take-home privileges. For people that aren’t familiar, there are Federal guidelines around how we do methadone and how much methadone a person can have with them at certain parts of their treatment. And those guidelines haven’t really been adjusted in a long time. And as they loosened on some of those guidelines for individuals, with still some discretion, we’ve seen some success. You know, one of the barriers with methadone is that you have to come every day. And there’s not a lot of people who can drop everything that they’re doing and come to a clinic every single day without some repercussions. So I really think that’s an opportunity and there’s a benefit in that, and something we can look at in allowing folks to have a little more privilege with their medication. I think really we’ve had a good opportunity to connect with people, too, during the pandemic. So, because of the need for education we were forced, or given the opportunity, to take more time with people. Just spend more time talking with and helping people – just in that area. And it’s been cool. We’ve really built kind of a community and a connection around that because we’re all going through it together.

- If you were able to work on a fantasy project to improve treatment and recovery support, what would it be?