Recovery Capital and Treatment Courts: A New Approach to Improve Client Outcomes

September 17 | 2:00 p.m. EDT

Join us at 2:00 p.m. EDT on Thursday, September 17 to learn how you can incorporate recovery capital elements into your program to improve client outcomes. This session will:

- Introduce you to the concept of recovery capital, including how to assist clients in building strong personal, social, and community connections.

- Demonstrate how to apply the concepts in your court staffing and program.

Research shows individuals with strong concentrations of personal, social, and community capital (recovery capital) are more likely to sustain long-term recovery. Whether you work in probation, treatment, case management, or court administration, learning about recovery capital will strengthen your professional toolbox.

Dr. Jacqueline van Wormer, an NADCP training and technical assistance director, will lead this training

The post Recovery Capital and Treatment Courts: A New Approach to Improve Client Outcomes appeared first on NADCP.org.

SAMHSA released the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Annual National Report this week.

One of the sections that’s gotten a lot of attention on Twitter is Substance Use Treatment in the Past Year.

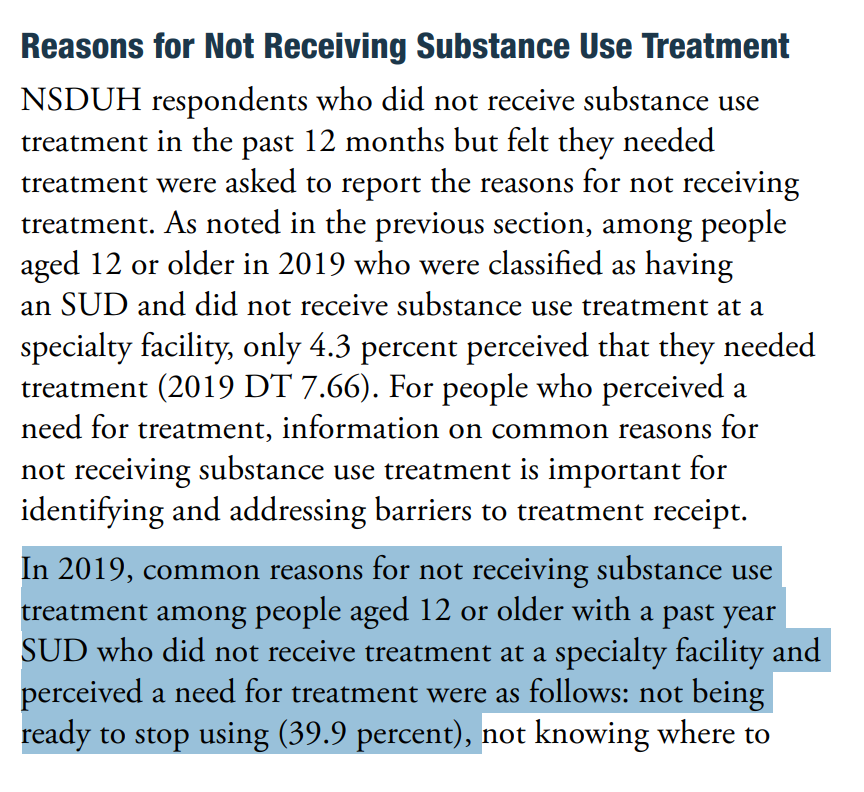

The item that seems to have received the most attention is Reasons for Not Receiving Substance Use Treatment.

In particular, that the most common for reason for “not receiving substance use treatment among people aged 12 or older with a past year Substance Use Disorder (SUD) who did not receive treatment at a specialty facility and perceived a need for treatment were as follows: not being ready to stop using (39.9 percent)” [emphasis mine]

The concern is that the emphasizing this as the top reason for not seeking treatment reinforces myths and stigma about people with substance use problems.

Let’s break it down

“not receiving substance use treatment” – This finding is based on people who did not receive treatment. People who did receive treatment are not included. So, this does not represent people with an SUD, just people with an SUD who did not receive treatment in the past year.

“among people aged 12 or older” – This finding includes a very large age range. Let’s look at the sub-ranges included:

- Among adolescents aged 12 to 17 in 2019, 4.6 percent (or 1.1 million people) needed substance use treatment in the past year.

- Among young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2019, 14.4 percent (or 4.8 million people) needed substance use treatment in the past year.

- Among adults aged 26 or older in 2019, 7.2 percent (or 15.6 million people) needed substance use treatment in the past year.

So, respondents aged 12 to 25 make up 37.5% of those included in this statistic. A couple of things come to mind about this group. First, we would expect lower levels of readiness to change among this group. In the case of addiction (the most severe form of substance use problems) the time between the first use and the first help-seeking is typically 4 to 5 years. We also know that earlier onset typically results in longer addiction careers. Second, we know that more than half of people under the age of 26 with alcohol dependence will “mature out” or experience “spontaneous recovery” without treatment.

“with a past year SUD” – This invites questions about how SUD is defined.

The report says the following, “The SUD questions classify people as having an SUD in the past 12 months based on criteria specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV).”

The DSM-IV had 2 categories of SUDs–Abuse and Dependence. The diagnosis is substance-specific (e.g. – Cannabis Abuse, Alcohol Abuse, Opioid Abuse, etc.) and Abuse is the less severe of the 2 categories of disorders. The diagnostic criteria are as follows:

A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one (or more) of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

- Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home (e.g., repeated absences or poor work performance related to substance use; substance-related absences, suspensions, or expulsions from school; neglect of children or household)

- Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous (e.g., driving an automobile or operating machinery when impaired by substance use)

- Recurrent substance-related legal problems (e.g., arrests for substance-related disorderly conduct)

- Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance (e.g., arguments with spouse about consequences of intoxication, physical fights)

One of the criticisms of DSM IV Abuse what that the threshold was too low for categorizing it as a disorder. For example, a college student who gets convicted of Minor in Possession of alcohol and is put on probation, and later discovered to be drinking again would meet diagnostic criteria for Alcohol Abuse.

The report does not break down the prevalence of Abuse vs. Dependence among the respondents.

It’s also noteworthy that most people meeting criteria for DSM Abuse will not need to abstain to resolve their problem–most of them will moderate their substance use without any help. The report also points out that many people who meet criteria for dependence will not need treatment and many of them will also be able to moderate.

I believe that the combining of these people with others who have chronic and severe substance use problems into the category Substance Use Disorders renders the category meaningless. This is an unpopular view in advocacy circles.

“and perceived a need for treatment” – This invited questions about how perceived need was determined. The NSDUH used the following question, “During the past 12 months, did you need treatment or counseling for your alcohol or drug use?”

I imagine that asking people if they needed counseling at some time in the past year for alcohol or drug use significantly lowers the threshold for inclusion into the group with a “perceived need” for treatment.

“not being ready to stop using” – The concerns raised in multiple tweets by multiple advocates centers on 40% of people with an SUD and a perceived need for counseling or treatment not receiving treatment because they reported “not being ready to stop using.” [emphasis mine]

That response indicates an assumption that counseling/treatment requires abstinence from use of (at least) the substance in question. As mentioned above, abstinence is probably not a necessary or appropriate goal for most people meeting criteria for DSM IV Abuse and many people meeting criteria for Dependence.

So … this option could capture any respondent with low problem severity, high insight, and ambivalence about abstinence.

What’s the problem?

Does this finding misrepresent people with SUDs?

Does it reinforce stigma?

I don’t know whether it reinforces stigma and I can’t say for sure whether it misrepresents people with SUDs. However, this highlights a problem I’ve posted about several times–SUDs is not a useful category. (Bill Stauffer also posted about it here.)

I’ll go further–the use of this category harms people with addiction and may increase stigma towards them.

- This category results in the conflation of people with lower severity problems who “mature out” and people who have chronic, severe, and treatment resistant addiction.

- This category results in arguments that moderation is an appropriate goal for the category. It also results in arguments that abstinence is the only appropriate goal for the category.

- This category too often turns “maturing out” into an argument against the need for treatment.

- This category contributes to the erosion of the conceptual boundaries of addiction and recovery.

Overshadowing stigma?

Among the complaints that this reinforced stigma was another complaint that the grouping of responses obscured stigma, which should have been listed as the largest reason for not seeking treatment among people who perceived a need for treatment.

This argument is based on 3 reasons that seek to quantify stigma adding up to 41.6%.

Stigma is a significant barrier to treatment, but I suspect that 41.6% overstates the role of stigma.

- It seems safe to assume that 100% of “might cause neighbors/community to have negative opinion” selections represent stigma.

- “Did not want others to find out” seems a little less clear. A lot of people don’t want others to know anything about their health or personal life. However, that desire for privacy typically doesn’t prevent people from seeking treatment. So, it’s probably safe to assume that most of these responses represent stigma.

- “Might have a negative effect on job” seems much less clear. This could represent fear of stigmatization or it could represent concern about required recurring appointments that might interfere with work attendance.

- Finally, respondents were able to select more than one reason. (The responses total 193.4%.) It’s probably safe to assume there’s some overlap with these three responses.

None of this suggests that stigma isn’t a barrier to treatment or that it’s unimportant. (This blog has 188 posts with the word “stigma” going back to 2006.) I just believe the facts are compelling enough without having to inflate the numbers of people suffering or recovering. I also worry that stigma is so frequently invoked as an explanation for nearly every “problem” in the field that we are eroding the meaning and impact of the term. I believe that doing so will eventually erode our credibility. (I put problem in quotes because many problems in the field are in the eye of the beholder.)

I believe the problem with the reports about the NHDUH is not the the way it’s presented, but the use of this category that includes people making unhealthy decisions about their alcohol and other drug consumption and people with chronic and severe forms of the disease addiction. Imagine a report on “respiratory disorders” that treats common colds and lung cancers as belonging to a single category.

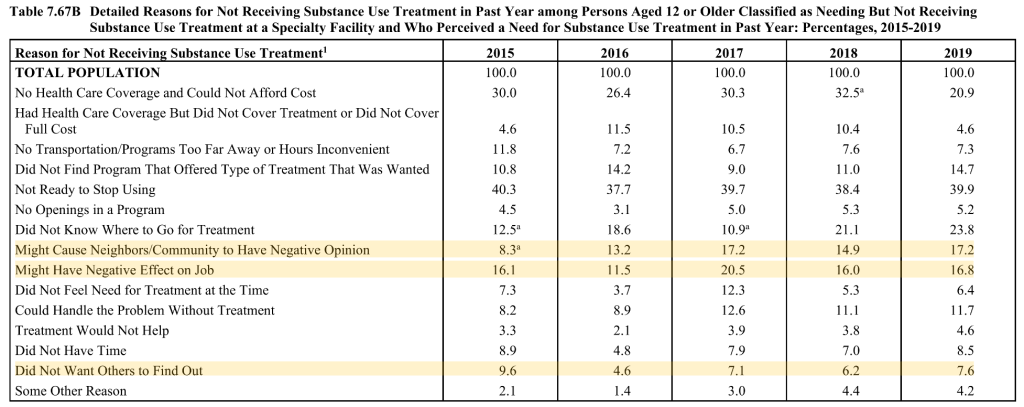

Action is in italics.

What one lacks is held in circles.

One asks for what one lacks.

September is Recovery Month, an occasion to focus on the needs of the millions of people in the U.S. living with a substance use disorder (SUD) as well as celebrate those who are trying or succeeding in putting drug use behind them. The stress and isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic are presenting enormous challenges for these individuals, but ultimately the altered realities of healthcare may create opportunities to reach more people with services and possibly even increase the reach of recovery support systems.

Significant increases in many kinds of drug use have been recorded since March, when a national emergency was declared and our lives radically changed due to lockdown and the closure of businesses and schools. In late April/early May, the Addiction Policy Forum (APF) conducted a survey of 1,079 people with SUDs nationwide, on how they were being impacted by the pandemic. Twenty percent of the respondents reported that their own or a family member’s substance use had increased since the start of the pandemic. And an analysis of a nationwide sample of 500,000 urine drug test results conducted by Millennium Health also showed steep increases following mid-March for cocaine (up 10 percent), heroin (up 13 percent), methamphetamine (up 20 percent) and non-prescribed fentanyl (up 32 percent).

Comprehensive national data are not yet available on overdoses, but data from some states such as Kentucky and Georgia as well as anecdotal reports suggest increases in overdose deaths and drug-related emergency room admissions in the first half of 2020 compared to last year. The Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program, a surveillance tool developed by the Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA), reported increases in overdose reports in 62 percent of participating counties nationwide, and that overall overdose report submissions increased by 18 percent after stay-at-home orders commenced in mid-March. Clusters of overdoses seemed to shift from urban centers to suburban and rural locations. (One state, Kentucky, subsequently experienced a decline in overdoses after the state reopened.) In the APF survey, 4 percent of respondents reported an overdose since the beginning of the pandemic.

There are many anecdotal reports that people with SUDs are having to wait longer to obtain treatment, and closures of treatment centers have also limited access. More than a third (34%) of the respondents in the survey by APF had experienced disruptions accessing treatment or recovery support since the start of the pandemic, and 14 percent said they were unable to obtain needed services. There are reasons to expect that lower-income people and minorities could be especially affected. Despite implementing widespread COVID-19 testing, community health centers, which predominantly serve disadvantaged populations, are seeing declines in patient visits and are experiencing staffing problems.

The good news is that policy changes facilitating telehealth and expanding access to medications for opioid use disorder may compensate somewhat for these problems. People with opioid use disorders can now begin treatment with buprenorphine without an initial in-person doctor visit, which used to be the rule. Methadone treatment previously required daily supervised dosing with tightly controlled take-home options, but patients deemed stable may now obtain 28 days of take-home doses; others may receive 14 days of doses. Changes to Medicare and Medicaid rules are also enabling telemedicine consultations for SUD to be reimbursed more easily. These developments may particularly benefit people who live in rural areas or who otherwise have had trouble accessing treatment in the past, and NIDA has provided supplemental funds to grantees to evaluate the impact of such changes. Inevitably, since many people with SUDs do not have computers or smartphones, other innovative methods, such as combining telemedicine with street outreach, will be critical to ensuring that all people receive the care they need.

The stresses of the pandemic and the social isolation resulting from distancing measures may take an especially great toll on people trying to achieve or in recovery from an SUD. Three quarters of the APF survey respondents reported emotional changes since the beginning of the pandemic, especially increased worry (62%), sadness (51%), fear (51%), and loneliness (42%). These emotions increase the risk for relapse, and unfortunately, circumstances since the pandemic have made peer support, for instance in 12-step meetings and similar groups, much more difficult.

While online recovery supports may not be an option for all and cannot fully capture the in-person experience, here, as in the realm of treatment, teleconferencing tools and smartphone apps are helping some people adapt to restrictions on physical gatherings. Several of the startups NIDA has helped through our Office of Translational initiatives and Program Innovations, for instance, have now adapted their tools to deliver counseling or facilitate peer connection during COVID-19.

COVID-19 continues to be an uncertain, ever-evolving reality, and its impacts are particularly being felt among those with addiction and those in recovery from substance use disorders. At this point, there is very sparse data on how SUDs are affecting COVID-19 susceptibility and outcomes, although findings are emerging and I will address them in a future blog. As we think about and support this community, this month and every month, we need to imagine and implement new ways of facilitating treatment delivery and needed recovery supports under these new circumstances.

Part of my job is teaching medical students about addiction and recovery, something I enjoy. Like others, I encourage future doctors to attend mutual aid meetings as part of their education. A couple of studies with this theme recently caught my eye.

In the first, 138 medical students attended an AA meeting and then wrote reflectively about the experience. The researchers found evidence that going to a meeting challenged students’ stigmatising attitudes and increased ‘flexibility of thinking’. They found younger students seemed to have fewer solidified biases.

In the second, medical students on a Family Medicine attachment attended a single AA meeting and again reflected on the experience. The researchers found that after being at a meeting, students were more likely to find AA a useful resource, were more likely to refer and felt more confident about explaining AA.

The researchers from both these studies state the value of the practice. In my experience, students rarely find mutual aid meetings dull. The power of the personal narrative can be compelling and evidence of altruism and mutual care is inspiring.

I suspect that such practices across the caring, support and therapeutic disciplines will have similar beneficial results and we should encourage all teaching settings in addiction treatment to embed this as part of their core delivery.

Event Description

Meeting Information

Meeting link:

https://ncgov.webex.com/ncgov/j.php?MTID=m744762fa0cc32d20dbb222102d8770f2

Meeting number:

171 166 3736

Password:

PHCNC

Agenda:

The Perinatal Health Committee of the North Carolina Child Fatality Task Force will meet virtually on Monday, September 14th from 10 am until 12 pm. The meeting agenda and meeting documents will be available on the Task Force website in the 2020-2021 folder in the Perinatal Health section of the site at the following link:

https://www.ncleg.gov/Documents/116#Perinatal%20Health

For more information about the Child Fatality Task Force, visit the Task Force website at:

https://www.ncleg.gov/DocumentSites/Committees/NCCFTF/Homepage/index.html

Since its inception in the late 1990s, a central goal of the new recovery advocacy movement has been assuring the representation of recovering individuals and families in the decision-making venues that affect their lives. As this movement matured, the complexities of achieving such representation became increasingly apparent. Dynamics within and beyond communities of recovery can threaten authentic recovery representation. Below are six critical dimensions of recovery representation and proposed benchmarks for each.

Authenticity of Representation is the assurance that those representing the recovery experience within decision-making venues are individuals and families with lived experience of recovery who are free from undue conflicts of interest. The problem that sometimes arises is that of double-agentry—persons who present themselves as representing the recovery community who, with or without conscious intent, represent instead personal, ideological, institutional, or financial interests. People with personal knowledge of the recovery process and the historical challenges faced by people seeking and in recovery free of such conflicted interests are the best suited for recovery advocacy leadership.

Guidelines: 1) Members of recovery communities are provided a voice in the selection of persons who represent their experiences and needs. 2) Those representing the recovery experience at public and policy levels possess rich experiential knowledge of personal and/or family recovery from addiction. 3) Persons representing the experiences and needs of people seeking and in recovery are free from ideological, political, or financial conflicts of interest that could unduly influence their advocacy efforts.

Depth of Representation assures a sufficient density of recovery representation within any decision-making group. The challenge is to avoid recovery tokenism, e.g., a single person asked to represent the broad range of recovery experiences and recovery support needs. Too many organizations exploit people in recovery to burnish their organizational image or superficially comply with an external recovery representation requirement, while affording little opportunity to affect policy decisions. Depth of representation also assures that people in recovery are at policy decision-making tables and not just involved in an advisory capacity, e.g., representation on governing boards as well as advisory committees.

Guidelines: 1) Recovery community organizations (RCOs) maintain authentic recovery representation greater than 50% at membership, board, and staff levels. 2) RCO leaders are drawn from individuals and family members in recovery or allies vetted by communities of recovery. 3) The RCO is committed to leadership development of its members. 4) Recovery representation in local organizational decision-making is commensurate with the degree to which recovery is central to the mission of an organization or project. The greater the focus on recovery, the greater the desired level of recovery representation.

Diversity of Representation assures the inclusion of people representing the growing varieties of recovery experiences and the diverse cultural contexts and community spaces in which recovery flourishes or flounders.

Guidelines: 1) The pool of available recovery representatives reflects secular, spiritual, and religious pathways of recovery as well as natural recovery and peer- and/or professionally-assisted recovery (including medication-assisted recovery). 2) Recovery representatives are knowledgeable about diverse communities of recovery and speak publicly not as individuals or representatives of one path of recovery, but on behalf of all people in recovery. (The fact that no one is fully qualified to do that helps us maintain a sense of humility, open-mindedness, and inclusiveness.) 3) Recovery representatives embody a spirit of anonymity—the suppression of self-centeredness—embracing and celebrating the wonderful varieties of recovery experience rather than competing for personal attention or pathway superiority. Falling short of these aspirational values is far too easy in the rarified air of public attention.

Stability of and Support for Recovery Representatives assures that people representing the recovery experience at the public level have sufficient recovery time and stability to offer a positive face and voice of recovery without threat to their continued recovery or their physical and psychological safety.

Guidelines: 1) Recovery representatives exemplify a recovery custodian orientation (rather than a celebrity orientation). 2) The custodian role properly places the focus on recovery messages and off the person or persons serving as messengers. 3) Recovery representatives exemplify servant leadership, affirming their role in serving the community. 4) Recovery representatives are not placed in roles involving physical or psychological risk without supervision and clear safety protocol.

Scope of Representation assures that people in recovery have a voice in shaping the full continuum of care related to alcohol- and other drug-related problems. Recovery representation is critical to effective AOD systems design, program implementation, service delivery, systems performance evaluation, and ongoing systems refinement.

Guidelines: 1) Recovery representation is included in policy and programming decisions related to primary prevention, harm reduction, early intervention, clinical treatment, community-based recovery support services, and the larger arena of alcohol and drug policy decisions. 2) Recovery representation is included in decision-making bodies charged with addressing common recovery challenges and resource needs, e.g., co-occurring health conditions, educational opportunity, employment opportunity, etc.

Public Enfranchisement assures that people in recovery are free from arbitrary restrictions on voting, holding public office, or exercising rights afforded other citizens.

Guidelines: 1) Local recovery community organizations exist and advocate for the full enfranchisement of people in recovery, including encouragement to vote and serve in public service roles. 2) People in recovery disenfranchised due to past addiction-related crimes have their full citizenship rights restored following release from prison or completion of probation or parole. 3) There are no state or local laws or regulations that otherwise suppress the voting, e.g., statutes requiring all fines be paid before voting rights are restored. 4) The addiction treatment and recovery support workforce fully reflects the diversity of the community, is provided a living wage, and is free of administrative burdens that interfere with service provision. 5) The treatment and recovery support system addresses barriers to employment and volunteer participation of people with lived experience of recovery.

Closing Reflection

Supporting and strengthening long-term recovery across multiple pathways of recovery and diverse cultural contexts must remain a central focus of our efforts. This is “the commons” of our movement for which we need deep, equitable, and inclusive representation in matters that effect our lives.

Nihil de nobis, sine nobis is Latin for NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT US and has been a rallying cry for democracy and disenfranchised groups for over 500 years. It means that no policy should be decided without the full and direct participation of those affected by that policy. We must ensure that our voices are included in all systems addressing alcohol- and other drug-related problems.

Link to Bill White Article HERE

Event Description

Where: Via Zoom https://www.zoomgov.com/j/1619096838?pwd=L3JORmFwaWEwcGN0NmxZS2pMMjJjdz09

Via phone:

+1 669 254 5252 US (San Jose)

+1 646 828 7666 US (New York)

Meeting ID: 161 909 6838

Passcode: 120530

Agenda is attached.

Why consider the change process, and what is the application of the ideas I will present?

- Clinical addiction professionals are trained in sequential change (Stages of Change, 12 Steps, etc.) rather than continuously wholistic, organic and dynamic change processes.

- Should we always assume and work within a staged approach?

- Clinical addiction professionals are trained in symptom reduction (drug use, craving management, managing triggers, drug refusal, etc.) and personal goal attainment (gaining employment, entering school, etc.).

- Should we only work in logical steps toward attainment of concrete goals?

- Clinical addiction professionals are trained in interviewing strategies that are targeted to bring about clinically-derived outcomes, goals, and changes.

- Should we overly-rely on questions, reflections and paraphrasing meant to bring about changes chosen by the counselor?

Could it be helpful to adopt a holistically-centered method with some individuals, rather than a method centered within fixed stages, concrete steps, and questions moving toward the counselor’s goals?

A 3-sided continuous process

In recent years I became interested in experiential and phenomenological topics. For me it was time for a change. My academic training in the 1980’s was rooted in models far from the experiential and phenomenological:

- radical behaviorism

- clinical behavior therapy

- cognitive therapy

- behavioral learning models of addiction (e.g. based on Pavlovian conditioning),

- and behavior modification methods for substance problems (e.g. controlled drinking).

And I had a resulting and rather limited range of clinical experiences over a fairly long period of time.

Exploring other sources, I found a body of academic and clinical research literature that was quite different, and focused on:

- themes and patterns of change

- dynamic change processes

- synergistic processes

- tension-release, both within a person and between a person and society, and

- critical thresholds that evoke change processes and movement.

Given my background in linear models (e.g. behaviorism, cognitive-behavioral psychology) and the length of time devoted to using my original training toward rather rigorous fidelity, I was ready for something new.

In this newer learning, I was especially intrigued by one article (Jorquez, 1983) in particular, because of two key factors related to change processes that were highlighted in that paper: extrication and accommodation.

- One factor Jorquez described as critical in the change process was extrication from addiction illness and the related context and lifestyle. Being extricated from the rubble of the past made sense to me. The idea of extrication seemed natural based on my clinical experience, and additional thoughts about change I was formulating.

- Jorquez identified a second key factor in the change process: accommodation of the new. After further reading on dynamic change, I found that the basic idea of accommodation is central to change overall. And it turned out that accommodation was natural for me to consider after all, given my academic familiarity with cognitive schema and social psychology.

After considering “extrication” and “accommodation”, I took the liberty of adding “shedding” to the ideas presented by Jorquez. I meant for “shedding” to hint at things like releasing and renouncing, especially as one moves through life seasons, and reconsiders life layers.

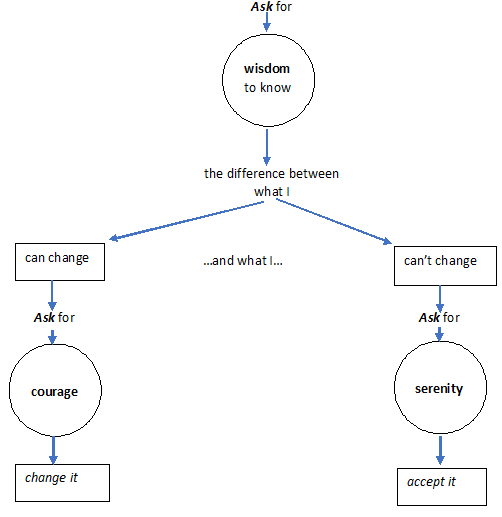

A Visual Diagram

I decided to represent the change process that happens during clinical work, as I had it in mind, with a four-sided gem (3 sides and a base).

Artwork: B. Schlosser

Artwork: B. Schlosser

The top 3 sides of the gem (as adapted from Jorquez) were:

- Extrication (from)

- Shedding (the old)

- Accommodation (the new)

And in my way of thinking about this, the top three sides rotate, shift, or move together. Or they are at least dynamically enacted concurrently in the moment (non-linear; see Resnicow & Page, 2008).

For me that made intuitive sense. And it fit over three decades of my clinical observations and two resulting conclusions:

- People often do not change in a linear or predictably-ordered fashion;

- People often do the work of multiple sub-processes of change (like extrication, accommodation, and shedding) simultaneously, over long periods of time1.

But what was the base of the object going to signify?

The base, or bottom, of the change process as I wanted to represent it would be the environment brought about by the clinician.

I was introduced to some articles related to the general idea of the therapeutic environment later in my career, and they hit me particularly hard – in a good way. So, my idea was of a very particular kind of clinical environment.

One article (Bion, 1967) discussed specific aspects of clinician memory and desire. The article described how a clinician could endeavor to have no memory of the patient or past sessions with the patient, intrude into the current moment. And it also described how the clinician could endeavor to have no clinically-imposed desire for the patient’s future over-ride the current moment.

- “No memory” of the patient was hard for me to accept. But the idea in the article was for the clinician to ask themselves if they are meeting with the person, or merely with their memory of the person? The point of the challenge was to direct one’s attention wholly to the person that is with the counselor in the now, rather than the remembered version of the same person as they were in previous meetings. That kind of push for deep empathic attunement held a lot of appeal to me.

I quickly added one more feature of the clinical space I was building: “no time”.

- That might sound strange. I’ll put it like this: since starting clinical work in 1988 I have never had a clock in my office. Why is that? When the patient sits down, I endeavor for time and the keeping track of time to go away. (Admittedly, working in residential settings my whole career and long-term residential for 19 of those years fed that freedom).

I also wanted “no question asking” to be included.

- During the Behavioral Health Recovery Management (BHRM) project our leadership team decided that the Achille’s Heel of addiction counseling is the over-reliance on asking questions. Across our entire agency at that time, we endeavored to mindfully eliminate as much question asking as possible, even while conducting assessments.

Thus, in my thinking on clinical environment, “no question answering” would also be a natural stretch-goal, in keeping with basic person-centered and motivational-enhancement methods.

Lastly, given my other recent reading in philosophy, I decided demands in science, philosophical assumptions, and forced applications of clinical art were all subject to “go away”.

Expanding on Bion with my additions, I developed my personal definition of what is otherwise called “the analytic stance”. And I decided to use my formulation of the analytic stance as the base:

- No time

- No art

- No science

- No philosophy

- No question asking

- No question answering

- No memory

- No desire

Adapted from: Bion, W. (1967)

A challenge

When I introduced my formulation of the analytic stance to a workplace colleague, and explained its use in this context, I was challenged to replace it with the therapeutic “common factors” (as they are called in clinical parlance). But I declined. Why did I decline?

I knew all too well from my relatively rigid fidelity-based past that the common factors of warmth, attunement, pacing and other behaviors that can be reliably observed and scored by trained 3rd party (rating) clinicians can be feigned while fidelity is met.

Using the “common factors” was not enough.

For my newer formulation of the change process the “analytic stance” as I defined it is my preferred operational mode. Why? To me it holds both the interior (less observable) and exterior (more observable) aspects of the whole person of the therapist with more validity related to purpose, compared to techniques that are easier to replicate or feign, are pre-packaged, and perhaps more shallow.

Looking back

This later-career self-study consisted of many articles concerning multiple models of recovery from addiction illness, 12 step facilitation as a clinical practice, the mechanisms of change in 12 step recovery (in both the treated population, and untreated population), and the history and development of the concept of addiction recovery as it applies to clinical therapy and related research. And it led to additional readings. It turned out that in doing that reading I came across some remarkably interesting notions about how some change happens for some people. And those notions were not of the kind I was accustomed to.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Katherine Mace and to Jason Schwartz for their comments on earlier drafts of this blog.

References

Bion, W. (1967). Notes on Memory and Desire. The Psychoanalytic Forum. 2:272-273, 279-280.

Jorquez, J. (1983). The Retirement Phase of Heroin Using Careers. Journal of Drug Issues. 13:343-365.

Resnicow, K. & Page, S. E. (2008). Embracing Chaos and Complexity: A Quantum Change for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health. 98(8):1382-1389.

Suggested Reading

1 Here we have a research observation that people undergoing addiction treatment might be simultaneously brainstorming hoped-for possible selves to pursue, feared possible-selves to avoid, refining and narrowing those choices over time, and developing and revising related action strategies – all while roughly progressing through Stages of Change relative to their SUD. Dunkle, C., Kelts, D. & Coon, B. (2006). Possible Selves as Mechanisms of Change in Therapy, in C. Dunkle & J. Kerpelman (Eds.) Possible Selves: Theory, Research and Application. (pp. 186-204). Nova Publishers.

Marquis, A., Douthit, K. Z. & Elliot, A. J. (2011). Best Practices: A Critical Yet Inclusive Vision for the Counseling Profession. Journal of Counseling & Development. 89: 397-405.

Thomas, C. (2013). Ten Lessons in Theory: An Introduction to Theoretical Writing. Bloomsbury Academic: New York.

White, W. L. (2007). Addiction Recovery: Its Definition and Conceptual Boundaries. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 33: 229-241.