Early this morning I noticed that Mike Dennis, the researcher at Lighthouse Institute, posted the following on his LinkedIn account:

Researchers and practitioners who access Bill’s website, williamwhitepapers.com, will notice a new look effective May 24, 2022.

Mike said the new address for Bill’s content is: https://www.chestnut.org/william-white-papers/ and that users navigating to the previous web address will be re-directed to the new site.

Mike added:

As Bill embraces retirement, he has transferred his writings, interviews, and archival documents to Chestnut’s website. All previous content remains.

I just wanted this to go out on Recovery Review so more people would be aware.

Disclaimer: nothing in this post should be taken or held as clinical instruction, clinical supervision, or advisory concerning patient care.

In his 1916 article1 titled “Mourning and Melancholia” Sigmund Freud grappled with clarifying the differences between melancholy and mourning. In his usage melancholy refers to what we would loosely call “depression” and mourning refers to what we would loosely call “grief”.

In that article he also grappled with the practical implications that arise from clearly differentiating them.

I read Freud’s article with interest.

“But why?”, you might wonder.

To help identify some reasons that I read that article with interest, I ask rhetorically:

- Do some patients in addiction treatment settings report a history of depression?

- Do patients undergoing addiction treatment sometimes report grief as a barrier to, or a side effect of, their personal change process?

- And can addiction counselors benefit from carefully considering these topics?

Across the decades of my career addressing chronic, complex, and severe addiction illness I have noticed these phenomena and would say “Yes” to all three of those questions.

And I have noticed addiction counselors:

- Must sort out the real differences between similar symptoms as representative of depression or grief (such as differentiating major depression from an adjustment disorder with depressed mood, and from bereavement);

- Often need to help the patient navigate the change process while the patient is experiencing something like grief… …over what they now realize they lost due to their active illness, …as they acknowledge some of the positives of their substance use lifestyle they must depart from, …when they consider losing the chemical itself;

- Commonly face a history of underlying depression that might be active now.

But what, if anything, can we gain from considering this writing by Freud?

“Various clinical forms”

I found it interesting that over 100 years ago Freud voiced a difficulty that is still a caveat today. About “melancholia” he wrote,

…whose definition fluctuates even in descriptive psychiatry, takes on various clinical forms the grouping together of which into a single unity does not seem to be established with certainty; and some of these forms suggest somatic rather than psychogenic affectations.

- The same could be said of substance use disorders at least insofar as neither mere use nor mere problematic use are the same as alcoholism or addiction illness.

- Even addiction illness itself seems to take on various forms, like a syndrome, rather than always having the same nature in each person when it is present.

- He wonders if some cases are largely biologically based while others may have other origins; likewise there is a wide variability in factors driving the early course of what does eventually become addiction illness.

“The loss of some abstraction”

But he goes on to contrast that by saying “mourning”:

…is regularly the reaction to the loss of a loved person or to the loss of some abstraction that has taken the place of one, such as one’s country, liberty, an ideal, and so on.

- This shows us a range of possible emotional barriers to recovery – the losses that moving forward might represent.

- From this we can consider that the shift forward out of active addiction illness could include various kinds of losses and a resulting emotional price for becoming well.

“Useless or even harmful”

And he is also careful to identify grief experiences that should not be considered a clinical disorder, don’t require clinical help, and that pass on their own.

Although it involves grave departures from the normal attitude to life, it never occurs to us to refer to it as a pathological condition and to refer it to medical treatment. We rely on its being overcome after a certain lapse of time, and we look upon any interference with it as useless or even harmful.

- The same could be said of substance use; not all use is disordered use.

- What are the indicators of disordered use that are not a “use disorder”?

- But this raises an interesting point. With today’s ultra-high potency substances, the course of addiction illness might be more survivable than simple use.

- In this way the topic of “severity” becomes more complicated.

- Mere use might be more threatening to a person’s wellbeing than a longstanding pattern of addictive use, depending on the substance, even when they have no substance use disorder.

“Disturbance of self-regard”

Comparing mourning and melancholia, he states,

The disturbance of self-regard is absent in mourning; but otherwise the features are the same.

- Across my career, in settings and services helping those with high problem complexity, severity, and chronicity SUD’s, “self-regard” is often harder to address than addiction itself.

- Shame. Existential shame. The list goes on.

- Addiction illness often includes this complication of self-regard and it is often a needed focus in addiction counseling, especially in the context of a relational network or family system.

- Flipping the idea of “disturbance of self-regard” on its head, I wonder, “What is the ego-syntonic way out of addiction? What new team or new tribe is a natural and positive/supportive fit for the person?”

“The economics of pain”

Concerning mourning he writes:

We should regard it as an appropriate comparison, too, to call the mood of mourning a ‘painful’ one. We shall probably see the justification for this when we are in a position to give a characterization of the economics of pain.

- The economics of pain brings much to mind from psychology related to understanding the etiology and course of addiction illness: homeostatic regulation of emotion2, cognitive dissonance, attribution theory, possible selves (both hoped for and feared)3, and the lack of effectiveness in stopping use of what would normally be considered overwhelming punishers4.

- My first clinical supervisor and I used the term “Hedonic calculus” as a concept and as a probe to help us better understand.

- We collaborated to identify the raw circuitry within, and resulting logic model for, the movement from normal use, into problematic use, and into and across the course of addiction illness generally.4

- And in my clinical supervision I was required to build a unique logic model of the hedonic calculus for each case specifically.

“The loved object no longer exists”

Reality-testing has shown that the loved object no longer exists, and it proceeds to demand that all libido shall be withdrawn from its attachments to that object.

- Here addiction illness differs from mourning. In treating addiction illness, the object continues to exist. How so?

- One object is the chemical itself. It continues to exist in the world. It is viable and available.

- And that object (the chemical) is often internalized in the recollection of the person we help. In that way it can sometimes be difficult to identify a helpful empty space as a point of grounded primacy from which change can proceed and upon which change can continue. (In this regard the strengths model can be so helpful; “Tell me when the problem does not happen.”)

- Given the relative permanency of the object, the emotion of the relationship can remain and sit as a latent force. Even if it is well grieved.

“What he has lost in him”

This, indeed, might be so even if the patient is aware of the loss which has given rise to his melancholia, but only in the sense that he knows whom he has lost but not what he has lost in him.

- Believe it or not, this makes me think of the family system and building a genogram. A typical genogram of the family system might show who is in the system and perhaps their individual standing relative to chemical use.

- But this language shows us one could prepare a genogram of the family system noting “what” has been lost, not just the “whom” of the present.

- We could diagram the “what” that has been lost inside each family member, each in their own estimation, concerning themselves, the family, the patient, etc.

- We could diagram the patient’s estimation of each family system member’s related losses.

- Thus, the clinician would apprehend a fuller panorama of meaning5, rather than merely know “who” is present and who is important.

“Which has become poor and empty”

Comparing mourning and melancholia, he states,

The melancholic displays something else besides which is lacking in mourning – an extraordinary diminution in his self-regard, and impoverishment of his ego on a grand scale. In mourning it is the world which has become poor and empty; in melancholia it is the ego itself.

- Here we see a separation of the alcoholic for whom alcohol is a problem, and the one for whom self is a problem. And of course, some may tell us for them it is both.

- The alcoholic seeing alcohol as a problem may be making things simple enough and progress well with our without “recovery”.

- Alternatively, that person may slip, or even progress in the illness – for the lightness of the effect of their estimation of the problem.

- And my clinical experience has shown me that the patient seeing self as a problem may, in so doing, be intentionally arranging victory or unintentionally arranging their own defeat.

“A loss in regard to his ego”

And drawing out some results of those differences he states,

The analogy with mourning led us to conclude that he had suffered a loss in regard to an object; what he tells us points to a loss in regard to his ego.

- In this it is simple enough to say that in his formulation mourning comes from loss of the object, while melancholy involves loss concerning ego.

- Addiction professionals helping people move from severe and complex addiction illness to wellbeing may at times need to determine if either of these losses are present, and coach the person served accordingly in navigating the emotions inherent in the journey.

“An object-loss was transformed into an ego-loss”

He expounds libido (roughly equal to “psychic energy”), the ego (roughly equal to “self”), and object in the context of loss:

But the free libido was not displaced on to another object; it was withdrawn into the ego. There, however, it was not employed in any unspecified way, but served to establish an identification of the ego with the abandoned object. Thus the shadow of the object fell upon the ego, and the latter could henceforth be judged by a special agency, as though it were an object, the forsaken object. In this way an object-loss was transformed into an ego-loss and the conflict between the ego and the loved person into a cleavage between the critical activity of the ego and the ego as altered by identification.

- Does the lost bottle or drink, or lost role they serve, make a clean break? And is that loss well mourned if and as needed?

- Or does the shadow of the lost object fall upon the ego of the patient in such a way that is experienced as an ego loss and serve as a barrier to recovery, promoting a drink?

- Does the patient identify with the bottle and in that way prevent change (e.g. superficially stating “I am an alcoholic, what do you expect?”), or face the reality in such a way that promotes change (e.g. “I’ve stopped drinking so many times, please help me.”)?

Closing Synthesis

Substance use, misuse, and use disorders might each take “various clinical forms”. Grief might be present, and the patient may not be well served if the addiction counselor holds “the loss of some abstraction” as a category of consideration without relevance and efforts to overlook it. Addiction counseling may be “useless or even harmful” if applied in the wrong way to the wrong person. Some people with clinically significant substance use disorders might have a clinically relevant feature in the “disturbance of self-regard”. If so, that might be relatively more difficult to identify than the use disorder itself. “The economics of pain” may promote or confound personal progress. Thus, the addiction counselor might be best served in this regard to privilege the expertise of the patient and have the patient explain what the costs are – for their condition worsening, remaining the same, or getting better. Just because “the loved object no longer exists” does not mean it is not recalled with affection or longing, even by the family members. (The related and various positive affections for and negative affections about the object, as well as the object’s various functions in the system, might need to be considered). The naïve helper might assume the word, idea, or identity of “recovery” per se as a goal are important and that all improvements relative to that are prognostically positive. The naïve helper might also fail to consider that the patient arriving for services as a hopeful indicator might conceal what the patient “has lost in” self – that they have “become poor and empty” or experienced “a loss in regard to his ego”. In this way, the addiction counselor may do well to include the moral dimension in their work and consider if “an object-loss was transformed into an ego-loss” – with two practical extensions. If such a loss is present and not properly addressed, the possibility of fertile reward might be left on the table, making the return to active illness a relief. And if such a loss is present, holding the possible utility of a recovery identity (and various related personal pathways within such an identity) might serve as a practically helpful existential option.

References

1 Freud, S. (1916). Mourning and Melancholia.

2 Solomon, R.L. (1980). The Opponent-Process Theory of Acquired Motivation: The costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain. American Psychologist. 35(8): 691-712.

3 Dunkel, C., Kelts, D. & Coon, B. (2006). Possible Selves as Mechanisms of Change in Therapy, in C. Dunkel & J. Kerpelman (Eds.). Possible Selves: Theory, Research and Application. (pp. 186-204). Nova Publishers.

4 Kelts, D. & Coon, B. (1994). The Acquired Hedonic-Cost Habituation Syndrome: Conceptualizing the Process of Addictive Self-Destruction. Unpublished manuscript.

5 Coon, B. Rescorla is to Pavlov as Semiotics is to Freud. May 12, 2022. Recovery Review.

After a few stops and starts in his recovery, Rick Kuplinski is well into his recovery journey using the SMART Recovery tools and resources available. He has also created a few of his own tools that he uses during his meetings. Rick’s mantra of Head. Heart. Feet. keeps his participants engaged with meaningful thoughts and takeaways after each meeting.

Learn more about becoming a SMART volunteer

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Maia Szalavitz is an award-winning, best-selling author and opinion writer, whose focus is on changing the narrative of addiction and recovery. Two of her books Undoing Drugs: The Untold Story of Harm Reduction and the Future of Addiction and Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction, are among a long list of publications that address this issue.

In this podcast, Maia talks about:

- Her New York Times opinion piece about Oregon decriminalizing drug possession

- How external forces undermine internal motivation

- How the Black Lives Matter Movement shows the racial disparities in the justice system

- That criminal drug laws aren’t based on science and how emotions are decision algorithms

- The debate over decriminalization is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of what actually works

- Explaining the analogy of addiction to that of falling in love or having a baby; people do crazy things

- People with addiction are not lazy, they are hurting

- Trying to punish our way out of addiction is not the answer

- Why it’s important to meet people where they are and welcome them to treatment

- Not calling doctor prescribed medication Medically Assisted Treatment (MAT)

- Why we need more expansive definitions of recovery

- How chronic pain patients are being negatively affected by the opioid epidemic

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Our substance use care system workforce has long faced very high turnover rates. One of the studies from years ago that always stuck with me as framing out the challenges and value of working in our field, was from 2003, the toughest job you’ll ever love: A Pacific Northwest Treatment Workforce Survey. It identified turnover rates of around 25% annually. It was part of a systematic review of workforce challenges conducted through our Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) system funded by SAMHSA.

My organization, PRO-A did a similar survey here in PA in 2013. Similar results have been found year in and year out nationally. That perpetual churn was associated with high stress work, low pay, and high administrative burden. This 2021 New York report found that program administrators identified a 44% of their counseling staff and 38% of support staff turn over every 1 to 3 years. They believe it is consistent with current national rates. Our capacity to sustain and strengthen our SUD workforce remains a significant challenge. When a crisis is measured in decades, we norm it. This is our situational normal. It is not the standard of workforce we need to have to serve those in need of our help across the nation moving forward.

On the eve of COVID-19, in May of 2019, the Annapolis Coalition released a report commissioned by SAMHSA noting that we needed an additional 1,103,338 peer support workers and 1,436,228 behavioral health counselors, as part of the 4,486,865 behavioral health workers conservatively estimated as our workforce gap. Enter the Great Resignation of 2021 and 2022. Looking back, such estimates ring as optimistic. We now have a debilitating strain on our public sector SUD programs who struggle to keep their census rates high enough to sustain their narrow margins of operation.

Data from beyond the SUD service system suggests that US workforce resignation rates are highest among mid-career employees and is now being termed boss loss in some circles. It may have a link to a loss of a sense of wellbeing as a recent report found that one in four workers left their jobs for mental health reasons. I recently wrote about this dynamic through the lens of a moral wounding to our SUD field.

Our SUD workforce was in a decade’s long crisis before the “great resignation.” Those dynamics got much worse and were shouldered by fewer workers, increasing the strain on key staff. The challenges may not go away in the foreseeable future. Left unchecked, they may have a synergistic effect, a negative feedback loop where newer workers are hired into programs that have lost the capacity to prepare them to be effective as a result of the severe turnover. Programs unable to sustain a focus of helping people heal from an SUD.

SUD service programs find themselves in a perpetual state of orienting new staff while experiencing a dearth of seasoned staff who have the institutional knowledge to transfer critical knowledge and skills to these new staff members. This churn is being exacerbated by the aging out of our existing SUD workforce and the loss of mid and entry level staff who are leaving for other positions either inside our SUD care system at higher resourced programs focused on private insurance clients or outside of the field to pursue more lucrative work not related to the SUD field.

Additionally, the destabilization of our SUD workforce is leading to the cannibalization of our field, particularly in the public sector. Struggling public funded treatment programs either undermine their fiscal stability in bidding wars with other such wounded programs to recruit staff to avoid cutting patient census numbers. Or, choose not to increase pay because they do not have the resources to do so and reduce their program capacity. This sets up longer term program deficits as their economies of scale are reduced. Both options lead to death from a slow bleed. These dynamics may not be things we readily see. We do not monitor the fiscal health of our public SUD treatment programs. This last point may be a thing to begin to do to get ahead of these trends and understand the implications of what is happening.

Programs are left with a Hobson’s choice of going broke now as they cannot admit patients who need help because they lack staff or go broke later by paying staff more than they can sustain to keep the doors open right now. Join the boss loss and abandon the work, go broke now, or go broke later. These are the choices administrators of public funded SUD service system programs are faced with in our era. It is not a sustainable dilemma.

So, what do? Some thoughts for discussion:

Recruitment

- Flip our workforce crisis lens from a deficit focus to a strength focus. People with lived experience are deeply committed to the community served. Let’s make it easier for persons with lived experience to get into and to stay engaged in the SUD care system over an entire career.

- Prioritize workforce development strategies that focus on making our SUD workforce more representative of the population it serves based on race, gender and lived recovery experience.

- Build a bridge into the field. Remove barriers for recovering persons who are passionate about doing this work such as degree requirements for entry level positions, criminal justice history barriers and other formidable front-end career blocking polices so that we can get those eager to do this work into our field.

Workforce Development

- Support worker development at all stages of an SUD workforce career from entry level to CEO. Every public program in the nation should be funded to support tuition reimbursement for their staff to help them stick, stay and grow.

- Supervision is the cornerstone for our entire field, yet it is unfunded and only supported as a peripheral need. Fund it, support it. Develop supervisors over the long term to improve the effectiveness of our whole service system.

- Establish a system wide national mentoring infrastructure to nurture supervisors as the key to more effective care.

Workforce Retention

- Acknowledge and support SUD workforce wellness as a collective responsibility of our entire service system.

- Examine regulatory standards and all relevant policies to expand the ability for SUD workforce employers to be flexible around employee hours and functions to meet the needs of a workforce that expects such flexibility.

- Include all staff in decision making processes so they know they are part of the outcome! Ensure that workers are included in decision making across all of our organizations and across all of our government partners.

Is there a tipping point in respect to loss of institutional knowledge as a result of our workforce turnover? A point of no return? The thing about tipping points is far too often one does not know it has been reached until after it has occurred. What happens to those fresh faces if what they quickly learn is that the programs are ill prepared to help them meet those objectives? I hear reports of new staff, eager to help turn into jaded workers in a matter of a few weeks under such conditions. Building out a supportive infrastructure and healing these programs would take a lot of time, resources and commitment, and well as seasoned staff who know what to do to turn them around. All things in short supply.

We should also always remember that there is reservoir of implicit bias in the general public against persons with substance use disorders and the systems that serve them. It is our inconvenient truth as our recent collaborative report Between PRO-A, RIWI and Elevyst, How Bad is it Really, Stigma against Drug and Alcohol Use and Recovery in the United States discusses. The less effective we become at helping people heal, the more that some in our society see this as evidence we do not get better and so helping us is not worth it. Funding and support decrease and effectiveness spirals even further. History shows us fairly clearly that when this happens, we shift back towards a punitive model. “Lock em up.” This is the ultimate risk of the tipping point, the other side of that seesaw of history. Let’s not go in that direction.

There’s a popular Chinese proverb that says: “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is now.” Let’s plant (and nurture) these trees now.

Someone relatively new to the substance use disorder area asked me recently why I thought there was so much division and hostility in the addiction and recovery field, compared to other parts of health and social care. Do we really have more conflict than in some other healthcare areas? There are strongly held positions which seem impossible to reconcile in all areas of life. Is addiction policy, advocacy, treatment, support and recovery any different?

After nearly 20 years of working exclusively in this field, my conclusion is that it probably is different. This is certainly something to be curious about. At the outset I want to be clear: I also believe that there is plenty of harmony too – much that binds us together and some great examples of collaboration in the interests of the people and families we are trying to help.

Some of the division is between harm reduction and recovery or, more precisely, around harm reduction, medication assisted treatment, and abstinent recovery. A great number of people have called this out as a false division, urging us toward a broad range of responses centred on people’s needs in the here and now and guided both by evidence and individuals’ rights to choose the recovery path that is right for them. Sometimes those voices are drowned out by polarising dissent.

Every week I hear strongly held perspectives on one side or the other of these fissures. Sometimes the antagonism to a particular approach is more subtle and we see exclusion and attitudinal barriers rather than overt criticism. At times we can tell more about an organisation’s or individual’s approach by what they don’t say.

For instance, in some circles the words ‘recovery’ and ‘abstinence’ are rarely seen or mentioned despite being important to some people trying to resolve their substance use problems. Similarly, other people consider opioid substitution therapy to be simply replacing one addiction with another, despite compelling evidence of reduction of harms. Pressure can be put on people to detox without adequate preparation, supervision or supports in place creating avoidable risks.

The question about the vigorous level of debate and fiercely held opinion we experience in the domains of addiction, treatment and recovery is a good one without a simple answer. I’ve been thinking about this since and here is my tuppence worth.

We are passionate

Many of us who work in addiction treatment are impassioned about substance use disorders and the responses we have to them. This passion is driven by personal and professional experience, by hope and as a response to the grim drug and alcohol deaths we see. Such passion drives beliefs and actions and can lead to progress and improvement in the lives of individuals. However, sometimes passion can be enacted as anger or arrogance. It can spill over into wrath or rage. On occasion, it can disguise fear.

These experiences which drive passion can be self-defeating or limiting. If you have made an abstinent recovery aided by 12-step fellowships, you may come to believe that this is the only way to recover – though, to be fair, many people in mutual aid groups will readily acknowledge that there are multiple pathways to recovery. Similarly, if you are not seeing evidence of people moving on to abstinent recovery and of them leaving treatment settings, you may believe that people do not recover or that it is much too dangerous to support such a path.

Then there is the danger of zealotry, driven by passion or fear – a blinkered approach which will not, or cannot see that we need a broad and welcoming church – a place that celebrates diverse approaches and pathways. When contempt for others creeps in, often unbidden, we diminish our effectiveness and authenticity.

This week in a newspaper I read an article where one treatment service explicitly undermined others, using misleading words. The effect was to distance the reader from some of the other good points made. The unintended consequence was disconnection, further division and a lack of positive impact. While we don’t need uniformity and we need to have the capacity to call out wrongs, we also need mutual respect. It’s a good value to hold close.

You can have no influence over those for whom you have underlying contempt.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

My fellow blogger Bill Stauffer recently noted that social media may not help us here. We connect with others who hold the same views as us and end up with confirmation bias or we get swept up in the wave of righteous indignation and then write things that are disrespectful, rude, or even threatening.

As a relative newcomer to Twitter, I was naïve enough to be shocked initially by some responses to my early posts and to what I saw as the reasonable perspectives of others. I follow many whose views `I do not agree with, but read what they post with interest, however I don’t tolerate abuse. We behave differently online than we do in person and indeed, social media may actually harm our emotional health. I am grateful for the mute and block buttons – wonderful inventions.

We are concerned

If we see our clients/patients dying of drug and alcohol-related causes when they do move out of treatment, we may think that it is too risky for anyone ever to move on. For those of us who work in addiction treatment and support, hearing about overdose and death is a chilling, upsetting and unwelcome part of the job. But being excessively worried and anxious about the safety of those we are trying to support can lead to unhelpful consequences.

Without adequate supervision and support we can begin to live with unrelenting and harmful levels of concern. Then we can begin to get burnt out or develop dysfunctional thinking and behaviour.

Concerns about detox and abstinent recovery need to be addressed, as do those around MAT and harm reduction. Myths need to be put to bed though. Reassuringly, there are plenty of practitioners who have reconciled those concerns in a way that allows them to work passionately across all areas, mitigating risks but not in a way that stymies the capacity of people to achieve their goals. I am in awe of some of them.

We have limited resources.

When funding is tight and demand is high or services are threatened, we can reflexively respond in defensive ways, or even attack others’ services. I’ve certainly experienced that in the past – people who are normally supportive behave in ways that are difficult to understand and everybody feels hurt and upset.

When resources are limited, you get people fighting their corner, but this can spill over into arguments about which services should be limited, have resources removed or be shut down. Think residential rehab for instance – often cited as ‘not evidence based’ by those who put their faith wholly in medical models, they can be seen as low hanging fruit when money dries up. I’ve experienced this more than once.

We get disenfranchised.

The reason we have a surge in advocacy and support for people with alcohol and drug problems is that they have not felt represented by the services set up to help them and have not felt that those services have met their needs. They have not had a voice. Or just as bad, when that voice speaks up, it is ignored, dismissed or treated with contempt. Perhaps, worst of all, individuals can sometimes be given a tokenistic place at the table – present but powerless. While huge power disparities persist, it is always difficult for lived experience to have any impact on policy and the shape of services.

Now when voices are beginning to be heard – and in Scotland those voices are likely to become more powerful and influential through the forthcoming National Collaborative – they can feel threatening to the establishment. Yes, we have our evidence that we base our treatment offer on, but now we have new evidence of a bit of a mismatch between what we have on offer and what individuals and their families want from treatment. We have a distance to go to achieve balance.

There are those who would shut those voices down, but the likelihood is that, in terms of visibility and volume, in the future lived and living experience is not going anywhere but up.

I will ensure that local panels of people with lived and living experience are involved in all local decision making, and that a national forum or collaborative is in place to better inform our national mission.

Angela Constance, Drugs Policy Minister

We lack the breadth of experience

Years ago, a colleague who had worked in the field for years told me he’d never met anyone in long term recovery from heroin addiction. At that point, I’d met hundreds, so we could agree that we’d had very different experiences – poles apart. If professionals don’t get to see sustained abstinent recovery, instead seeing people remaining in treatment for many years or indeed experiencing too many deaths of clients or patients then of course it’s going to feel pretty risky to support people to the goal of moving out of services all together.

Equally, although I now work in residential rehab, working in harm reduction and medication assisted treatment settings in the community has helped me see the need for a broad spectrum of approaches to help individuals achieve their goals. Recovery is dynamic and non-linear and needs flexible and wide-ranging approaches to support it.

We are all a little prone to suffering from the Dunning Kruger effect, a cognitive bias where we think we have more knowledge and skills than we actually do on an issue. If all practitioners got to spend some time in different settings (from injecting equipment provision and wound care through to community and residential services and get a robust introduction to community recovery and support resources) then we’d perhaps seen more harmony and mutual respect.

We don’t always know ourselves

We go into caring roles for a variety of reasons and not all those reasons are apparent to us as individuals or to others. For some of us, growing up with addiction in our families can lead to a healthy desire to help other families. For others, unresolved wounds and conflicts from early life can hamper such efforts. We may not have tended to those early wounds or even be aware that they are still tender and are influencing our behaviour in the here and now. Other formative experiences can lead to a variety of motivations.

Some of us have a desire to rescue, we might be subject to countertransference, or we can collude. I have seen harm come to individuals on occasions, thankfully rare, where over-involved practitioners with poor boundaries conspire with their clients against the very services that are most likely to be able to help them.

When dealing with people, remember you are not dealing with creatures of logic, but with creatures of emotion, creatures bristling with prejudice, and motivated by pride and vanity.

Dale Carnegie

Some of us feel threatened when those who have depended on us for help want to become independent and move on. We may resist routes that can lead people to ‘abandon’ us. I have heard so much resistance to mutual aid, for instance, across my entire career in addictions – way beyond what is logical or reasonable – that it makes me wonder just what it is driving it. Could the lack of tolerance and acceptance be in part the fear of being divested of our charges, the pain of potential loss?

I’ve heard it said that without self-care we are prone to absorbing some of the disordered behaviours and thinking that can impair our clients – in a sense soaking up some of the pathology of addiction. Good supervision can increase insight and help to prevent this, but where supervision is not available or not utilised, disharmony and friction can develop and spread. Organisations and individuals who have a tendency to blanket-blame and shame others (others for the most part who are genuinely doing the best they can) may be suffering from this. Difficult people and difficult cultures exist, and we need to find ways to deal with them, exhausting though that may be.

Just because you’re dealing with difficult people, does not mean that you must become like them.

David Leddick

The work is challenging

Supporting people with substance use problems can be rewarding, but it can also be challenging. The high rates of death for those with alcohol and other drug problems are distressing. Disclosure of trauma and adverse childhood experiences can be difficult to hear and leave us lingering anxiety and disquiet. Sadness, anguish and grief can steal in and set up permanent home.

We can continue working but begin to detach or distance to the point where we become less empathic and compassionate. When we struggle like this, we may be less tolerant or even become cynical. Our relationships with others can then suffer and we take on a negative mantle but fail to recognise what’s happening. High sickness rates and excessive turnover in teams can be a reflection of this.

The way forward

And the solution to the bellicosity? You’ll need a smarter person than me to give a definitive answer to this.Addressing similar issues, Bill Stauffer quotes something that resonates with me ‘we no longer unite on things we agree on, we come together focused on things we hate’ – while this is not my whole experience, I am afraid that there is a kernel of truth here.

Love difficult people. You are one of them.

Bob Goff

A fundamental principle to moving forward is first taking a look at the part we play in this ourselves. What’s my thinking and behaviour like?.

We must examine our own flaws and blind spots in order to understand our common ground.

Bill Stauffer

Further, were we to focus on common ground, perhaps we could bring healing and consensus. On my best days I try to find that middle way, but as I say, I’m passionate too, my opinions are forged in a crucible of fire, I react to what I understand as others’ unreasonable positions, and I have my own blind spots. Sometimes I sit comfortably in my own echo chamber. There is a real risk that we lose sight of the people who we are trying to help as we pursue our own agendas.

The reason I’m mostly writing in first person plural (‘we’) is that I recognise many of these tendencies and vulnerabilities in myself. I get passionate, frustrated, angry and hurt, but when I take ownership of these reactions rather than blaming others, it gets easier for me to move forward. If I ever get good at this, I’ll let you know.

Show respect even to people that don’t deserve it; not as a reflection of their character, but as a reflection of yours.

Dave Willis

I have learned though that I don’t have to show up to every argument I’m invited to. More positively, I have found that when you bring people together, create connection and offer a safe space for dialogue, listening and exchange of ideas, you build bridges instead of barricades. There are values that need to underpin this approach – curiosity instead of condemnation, compassion instead of conceit, kindness, respect, willingness to learn, and a genuine desire to relate to one another.

You have brains in your head. You have feet in your shoes. You can steer yourself, any direction you choose.

Dr. Suess

When those new to the addiction field question how unhealthy it seems, we all ought to sit up and take notice. We are responsible for the culture we have created. If that is a culture of conflict, we need to attend to it. Leaders have a particular responsibility here – we ought to be held to a high standard of behaviour and professionalism. That need not make us impotent, but rather be mindful of the power that we hold and how we use it. Change starts with ourselves.

There’s one more thing – another value – that is missing when there is turmoil. That value is humility. It’s not reasonable to expect that we all agree on everything all the time. This would be a disaster – we need to feel discomfort, disagreement and passion; these can be potent drivers for positive change, but perhaps a little bit of ‘I could be wrong and others right’ would go a long way to pour oil on troubled waters.

Adam Grant, the organisational psychologist, nails it when he writes: ‘At the root of our polarisation problem is a deficit of intellectual humility’.

I’ll leave you with the same question that I’m holding on to. What can I/you do to heal division and help our field to be more effective and a healthier place to practise? How do we hold our convictions passionately, be authentic in challenging poor practice and behaviours, yet foster consensus and harmony? I’m really interested to hear your thoughts.

Continue the (respectful!) discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

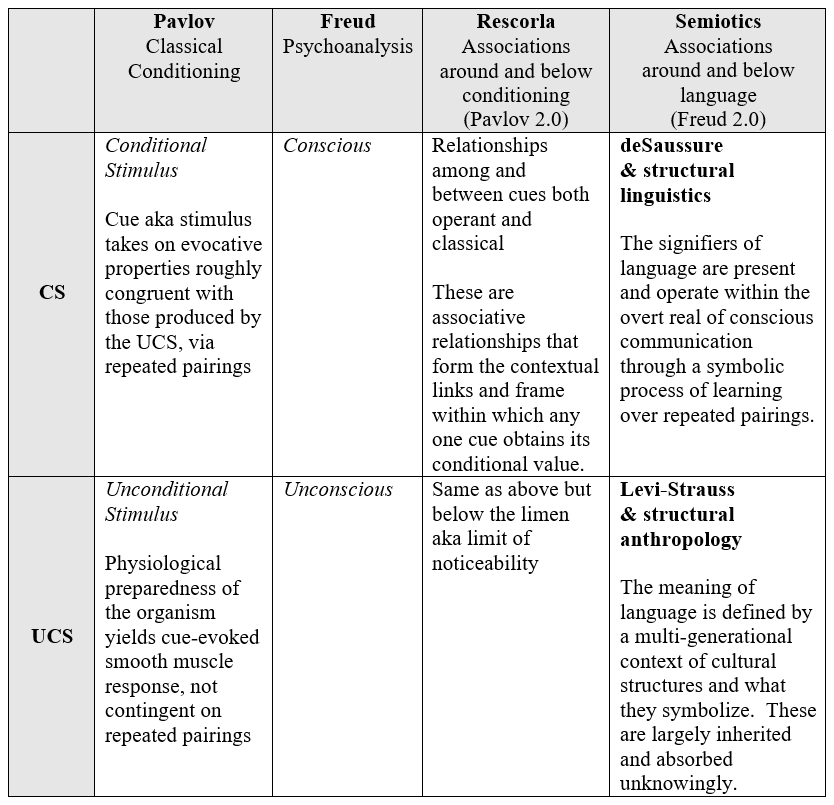

A few weeks ago, while I was reading in the psychoanalytic literature, I saw that Freud (1915) abbreviates the Conscious mind with the initials “CS” and the Unconscious mind with the initials “UCS”. To me this seemed like much too much of a coincidence.

Why did it seem like a coincidence? From my rather extensive background in behaviorism, I know all too well that in the classical conditioning literature CS means “conditional stimulus” and UCS means “unconditional stimulus”.

Many undergraduate students are familiar with Pavlov’s preparation involving presentation of meat to a dog, the dog salivating, and then repeated pairing of a bell just before presentation of the meat over a series of days. The bell eventually evokes salivation without the presence of the meat. In that arrangement, the unconditional stimulus (UCS) is the meat and the conditional stimulus (CS) is the bell. After repeated parings a conditional response of salivation to the bell is developed, and that response is nearly identical to the unconditional response of salivation to the meat. That is to say, after repeated parings the bell comes to evoke salivation and previously the bell was neutral concerning salivation.

Classical conditioning (ala Pavlov) and operant conditioning (based on rewards and punishers ala Skinner) are often derided as an intellectually dead-end area of psychology. But they are much more than most people know them to be. And when our internal book club this year (2022) initially focused on Semiotics (and later in the year focused on Jacques Lacan) I was struck by a very significant parallel I realized between Semiotics and a special area within conditioning theories.

The parallel I noticed had to do with work in conditioning by Robert Rescorla. His work was central to my master’s thesis and related research Eric Corty and I published in 1995. In short, Rescorla highlighted the elaborate cue context within which Pavlov’s simple conditioning paradigm sits. Rescorla emphasized the meaning between and among the numerous cues collectively (time of day, various physical signals such as positional balance, and the full array of overt environmental cues) that are always present in any context. He added these considerations to the much more narrow arrangement Pavlov studied. Rescorla showed that there is an elaborate interplay among all contextual cues, and the conditional response varies as it depends upon the interplay of these cues and signal differences of meaning for the organism. Under conditions x, y, and z, the CS might take on a very different meaning than it would under very different conditions a, b, and c. Thus, Pavlov’s dog seems to salivate or not depending on internal representations of the meaning of the cues, rather than simply transferring a conditional reflex from a cue the animal is born to appreciate to a single neutral one.

Early this year we studied Ferdinand deSaussure and his work on structural linguistics. In short his work included how a cue can take on representational meaning: a sound may be a word in a language or a shape may be a sign with culturally bound significance. For deSaussure the signifier (e.g. a red light) and the signified (e.g. “Stop!”) are connected arbitrarily and with culturally bound meaning. For deSaussure any one word is studied in its current context within the language system, and not for its etymological history. Later in the year we learned how Claude Levi-Strauss applied deSaussure’s structural linguistics to the study of anthropology. He argued that an archeological artifact is a sign within a temporally bound culture system and must be understood within the cultural context of its place and time. Freud’s work on the content and operation of the human mind can be held as contextualized and amplified by these two theorists.

After a few weeks of further reading per our normal schedule, and my continued meditation on the exact parallel between Semiotics and Rescorla, I formed the following grid.

Overall, I see congruence in Pavlov and Freud dealing with both the overt (signifier) and the covert (signified) as drivers of what is – via association. And I see congruence in both Rescorla and Semiotics dealing with advancing their respective models via a multiplicity of cues (the surrounding content and context) and the relationships those form on horizontal and vertical axes. As you can see from the grid below, Rescorla is to Pavlov as Semiotics is to Freud.

Chapter excerpted from the upcoming book:

ADDICTED IN FILM

Movies We Love About the Habits We Hate

(And How They Can Help Anyone Recover Successfully

and Lead a Happier Life)

by Ted Perkins, facilitator and “Tips & Tools Guy”

Reserve your copy today!

100% of all future proceeds, from any Bookshop sales, will be donated to support SMART Recovery.

Note: this review of Dopesick TV series expresses the opinion of Ted Perkins only, and is not intended to express the views of SMART Recovery as an organization.

I’m the first guy to tell you that movies and TV shows are a business first and foremost, which is why most screenwriters and producers like me strive to make them as provocative, romantic, comedic, horrifying, and/or thrilling as possible. Unfortunately, many media critics bemoan the negative impact of commercial imperatives on “quality” storytelling, and why Marvel superhero franchise films usually take the brunt of the criticism. But Hollywood is also known to take chances from time to time, and some of its greatest artistic and public-service accomplishments have occurred when it dramatizes important current events. Hulu’s original series DOPESICK is a prime example of how producers endeavored to take on a difficult and challenging issue like the opioid epidemic and hit it out of the park.

It must have been no small undertaking. The now well-documented and exhaustively researched story of how Purdue Pharma and the Sackler Family managed to flood the country with a highly addictive pain medication like OxyContin could fill volumes. For an in-depth look, I highly recommend Patrick Radden Keefe’s bestseller Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty. HBO also produced a powerful documentary on the subject called The Crime of The Century. These two dispassionate takes on the story are vital to the national discourse on the topic, but with DOPESICK the producers have managed to give this complex story a deeply human, very emotional dimension.

DOPESICK tells the OxyContin story from several different vantage points—from the coal mines of West Virginia to the Boardrooms of Purdue Pharma to the halls of the FDA. The story is anchored around no-nonsense country doctor Samuel Finnix, played by Michael Keaton, in a role for which he won the 2022 Golden Globe Award for Best Performance by an Actor in a Miniseries. If you haven’t seen his acceptance speech, I highly recommend you watch it on YouTube. The series itself is an emotional rollercoaster as it is; Keaton’s speech in real life takes it to a whole other level.

Finnix is an everyman good guy family practitioner who dotes over his low-income patients in a small West Virginia mining town. Many come in for help with the injuries and the associated chronic pain caused by hard physical labor in the mines. One of them is Betsy, played by Kaitlyn Dever, who suffered a back injury. Her physical pains are further compounded by the emotional stress of keeping her sexuality a secret from her Christian parents and community. Writer/Producer Danny Strong made a wonderful decision to humanize Betsy in such a way that her subsequent fictional addiction to OxyContin is caused by a multiplicity of factors (physical and emotional), just like addiction is in non-fictional real life.

Betsy’s injury just happens to (unfortunately) coincide with the rollout of a new “miracle drug” pain medication called OxyContin. Finnix learns about it when he receives a visit from a polished drug sales rep named Billy, played by Will Poulter. Billy’s the pride of the Purdue Pharma sales and marketing department, a boiler-room that thrusts young and eager 20-something overachievers into every doctor’s office in America to sell a lie: OxyContin isn’t addictive. While Finnix has enough common sense and medical knowledge to doubt this spurious claim, Billy’s sales pitch does sound pretty compelling. So, he writes Betsy a prescription for her pain. And to test OxyContin out for himself, he tries one (but just one) pill from the countless free samples Billy leaves behind as promotional freebees. You can guess where this is going.

The story then rewinds a few years to show the architect of all the ensuing misery, Richard Sackler, played with surreal creepiness by Michael Stuhlbarg. Somewhat miraculously, the writers have managed to humanize one of the most despicable characters in recent memory. Sackler comes off as a sad rich kid overshadowed by the achievements of his father and grandfather. OxyContin—a new “blockbuster drug” —is his desperate attempt to earn his family’s love and respect. So, what if, for him to earn his gold star, it’ll endanger and destroy the lives of hundreds of thousands of people? Ah, the banality of evil.

What is so striking about DOPESICK is the way the story goes on to portray the complexity of how Sackler and his Purdue Pharma foot soldiers cleverly managed to manipulate, dupe, and/or bribe seemingly respectable doctors and medical opinion leaders into endorsing a product that even a first-year medical student could have told you would be highly addictive. Purdue even put one over on the FDA to keep OxyContin off the list of heavily controlled substances. Equally fascinating (albeit horrifying) is how Purdue’s sales teams continually doubled down on the lies told by their sales reps every time anyone raised a red flag. And if that didn’t work, they just doubled and quadrupled the dosages per pill in order to combat “Breakthrough Pain,” a made-up medical condition that was really just users building up a tolerance to the drug and needing higher and higher dosages so they wouldn’t get dopesick. Talk about pouring gasoline on a fire.

With Sackler and Purdue firmly established as the ultimate Goliath, the story then introduces us to the Davids, no-nonsense country lawyers Richard Mountcastle (the always amazing Peter Sarsgaard) and Randy Ramseyer (John Hoogenakker). Their slow and methodical search for the truth, and their crusade to bring Purdue and the Sacklers to justice, plays out like an Agatha Christie mystery crossed with Erin Brockovich. To call these two guys “heroes” is an understatement, both in the series and in real life. Mountcastle gives up any semblance of a personal life during his decades- long investigation. Ramseyer even goes so far as to refuse to take OxyContin to relieve the pain of his prostate cancer surgery. Not because he thinks he’ll become addicted, but because it would put more blood money into Richard Sackler’s pocket.

Equally heroic is Bridget Meyer, a scrappy and ambitious DEA agent played by Rosario Dawson. Dawson does a superb job of looking calm and collected (albeit indignant) as the OxyContin catastrophe unfolds in plain sight all around her. Her sclerotic agency seems to be too afraid of intergovernmental red tape to do much about it, and she gets stonewalled at the FDA—an agency seemingly beset by an admixture of dark money influencers (mostly funded by Sackler) and unscrupulous regulators (many of whom went on to cushy six-figure jobs at—you guessed it— Purdue Pharma!).

As the conspiracy investigation unfolds, we eventually circle back around to Purdue’s primary victims in the story, Dr. Finnix and his patient Betsy. Her well-intentioned effort to use OxyContin “as prescribed” for pain quickly spirals out of control. She’s reduced to turning tricks in seedy back alleys after she loses her job for being high. Overly dramatic made-for-TV overkill? Not at all. Betsy’s fictional story is similar to that of many people swept up in the opioid crisis in real life. Most had jobs, were well-educated, had families, paid their taxes, walked their dogs. The farthest thing from their mind was to become addicted to drugs. Problem is, they had pain. Real physical pain. And for that they simply wanted help. But they got something else.

Finnix (Michael Keaton), the one guy you’d think would know better, quickly gets consumed by the drug as well. Desperate for money, he gets recruited into the Purdue Pharma “Speakers Series”—basically Ted Talk for OxyContin apologists and liars. All he has to do is step in front of the mike, say he’s an MD, and tell everyone the drug isn’t addictive. And all of this as he himself is addicted and high as a kite. Granted, Finnix is a fictional character, but his path to the “dark side” mirrors that taken by countless other once-respectable medical professionals who the Sacklers bought off to help them overcome critics and move more inventory.

What makes DOPESICK especially relevant to the overall conversation about recovery is just how difficult it was for treatment providers and mutual support groups to combat such an addictive drug. Betsy white-knuckles it at 12-Step meetings and attends group prayer at her church. But neither NA nor the Almighty seem to be any match for Purdue Pharma’s “miracle pain reliever.” While Narcotics Anonymous may have helped some individuals overcome their addiction, in Betsy’s case her meetings turn out to be secret OxyContin swap meets. (I have reached out to long-time SMART Recovery facilitators to see what their experiences were with meeting participants struggling with OxyContin addiction at the time.)

Finnix, meanwhile, loses everything, including his medical license. He goes to a rehab facility. However, like many people legally mandated into recovery, his initial (defensive) reaction is to feel like an outsider. He’s not addicted like “those people,” no sir. What’s worse, he realizes that many of the other patients at the facility have cycled through several times before. Whatever it is that’s supposed to be “working” in this rehab facility clearly isn’t. But that could be said about many rehab facilities at that time. When it came to the fight against OxyContin, literally everyone in the recovery universe seemed to be boxing outside of their weight class. Such was the power of this drug. Finnix eventually leaves the facility, relapses, then seeks recovery help at a methadone clinic.

DOPESICK culminates in Mountcastle and Randy Ramseyer’s successful prosecution of Purdue’s deceptive marketing and business practices. This eventually led to Purdue’s bankruptcy and multi-billion-dollar settlements (still in contention today). It’s a satisfying ending to a sad story, but in many ways it’s cold comfort. It took the U.S. judicial system more than a decade to put a halt to a tragedy that was blatantly obvious to anyone who cared to look. Thousands of people died needlessly. Entire communities were ravaged. All while the Sackler family made billions. So, was it just the Sacklers’ fault? Well, yes and no.

DOPESICK lets us peel back the curtain and see all the moving parts of this consumer product catastrophe. It was a perfect storm of contributory negligence. Purdue’s chemists knew the drug was highly addictive, so they bribed medical professionals to say it wasn’t. They submitted skewed data sets with sampling errors to regulators, whose job it was to know better. Purdue’s legal team knew they would never pass muster with the FDA, so they rewarded the FDA chief (Curtis Wright) with a $400,000 a year job at Purdue if he would help them create a loophole. Purdue’s marketing department knew the drug was addictive, so they paid users to say it wasn’t in promotional videos. Purdue’s sales department was under pressure to meet its targets, so they offered ridiculous commission structures to motivate its avaricious young sales teams. Yes, everyone at Purdue could say they were “just following orders.” But that didn’t work at Nuremberg, so why should it work here?

Not surprisingly, we see money at the root of this evil. A perverse amount of money. The financial incentives created by Purdue to market and sell the drug cascaded down the value chain. Small private pharmacies could mark up OxyContin and make higher margins on its sales (but in all fairness, they were also afraid that Purdue would sue them if they didn’t sell the pills). Medical and treatment professionals with prescription privileges stood to make a lot of money too. After all, they were helping people manage chronic pain, right? And thus, the infamous “Pill-Mills” formed around the country. Watchdog groups could reap millions in off-the-books “sponsorship” revenue from Purdue if they looked the other way. If all of this doesn’t smack of a criminal conspiracy, what does?

By revealing the interdependence of all these bad faith actors, DOPESICK does a wonderful (if maddening) public service. It illustrates how actual conspiracies work. How criminality is allowed to fester in plain sight because it seems too outlandish to believe it’s actually happening (I’m reminded of the quote attributed to Edmund Burke: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing”). This situation demonstrates how a lie told enough times eventually becomes the truth. And if that doesn’t work, just pay more people more money to parrot your talking points. These are painful lessons society seems to have to relearn over and over

again.

I also think DOPESICK is an important series to watch because it’s an unflinching look at addiction in general. Both what addiction is, and what people think and say it is. OxyContin is a case study in how real societal harm and death is caused by the language we use to describe and stigmatize individuals who suffer from addiction. We often hear in church, “Love the Sinner; Hate the Sin.” Well, the Sacklers made billions and avoided criminal prosecution by just flipping the sentence around: “Hate the addict, love the addiction.” OxyContin was harmless. The Sacklers were innocent victims of a vast left-wing anti-business conspiracy. It’s all the “pill-heads’” fault. Sound crazy? No, not at all. The Sacklers were just channeling the idea that addiction is a moral failing, completely unmoored from any physiological or mental health considerations. This idea is out of date, it’s wrong, and it’s killing people. SMART Recovery’s been saying this all along and will continue to say it as part of its support of Harm Reduction. Luckily, public views on addiction are slowly changing thanks to groundbreaking work by scientists like Dr. Nora Volkow (recently featured in a SMART Recovery webinar).

While DOPESICK spreads out culpability for the OxyContin Opioid Epidemic among many participants and institutions, I’m reminded of something my father once told me: “The fish rots from the head down.” And in my mind, that rotten head was Richard Sackler’s. He was the architect of the drug, the crimes, and the coverup. To date, he and his minions have avoided criminal prosecution in exchange for billions in civil settlement fines. As you read this, these settlements are still under review and appeal. On the one side, victims are demanding personal accountability from the Sacklers; on the other, states desperately need that settlement money to help clean up the mess they made. The Sacklers recently participated in a court proceeding where family members of OxyContin victims were allowed to confront their tormentors. Richard Sackler joined via Zoom, but only because he was forced to. His camera was turned off.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Avoiding Complacency

Whenever we accomplish something, we naturally feel excited and proud of ourselves. After leaving treatment, those in recovery are especially proud – they have just dedicated time and effort towards self-improvement and making lifestyle changes. However, recovery is not a “one and done” achievement – it is something to constantly work towards, which is why addiction is known as a chronic disease.

When first leaving treatment and during the e arly recovery period, people feel empowered and strong in their recovery, happy about all they have accomplished. They may feel they are at a point where they can take a break and remove recovery from the top of their mind. This leads to complacency. Complacency is defined as “self-satisfaction, especially when accompanied by unawareness of actual dangers or deficiencies.” Here are a few common reasons why people become complacent in their recovery – along with strategies on how to avoid complacency and focus on long-term recovery.

arly recovery period, people feel empowered and strong in their recovery, happy about all they have accomplished. They may feel they are at a point where they can take a break and remove recovery from the top of their mind. This leads to complacency. Complacency is defined as “self-satisfaction, especially when accompanied by unawareness of actual dangers or deficiencies.” Here are a few common reasons why people become complacent in their recovery – along with strategies on how to avoid complacency and focus on long-term recovery.

- Don’t ride the pink cloud – Most people in recovery have heard of, or experienced, the “pink cloud” – a period within early recovery where a person feels euphoric, proud, and excited. There’s nothing wrong with being positive and optimistic after achieving a goal, but the pink cloud can take over and make you avoid facing the reality of long-term recovery as you “float” above the world, forgetting about real challenges in recovery like navigating work, relationships, and aftercare. Use your early recovery period to build a plan for tackling these long-term issues instead of riding the pink cloud, and you’ll already be a step ahead.

- Don’t lose sight of the bigger picture – Early recovery is important, but it is only part of the journey. Focusing too heavily on early recovery can cause you to lose sight of your end goal, which is maintaining recovery over a long period of time and incorporating recovery into your everyday life.

- Keep up with the program – After 90 meetings in 90 days, you may feel like it’s time to relax. Many people return to use after 90 days because they feel like they have their addiction under control by that point. Attending meetings and keeping in touch with your sponsor are crucial to successful recovery. Without that constant support and reinforcement, it’s easy to trail off into relapse.

- Continue to be of service to those in your recovery network as well as your community. Giving back is a main tenet of the 12 Step Program because it allows you to feel good about yourself and help those around you, all while keeping recovery a priority. Again, keep long-term goals in mind, like becoming a volunteer or program speaker after a year of sobriety.

It is all too easy to fall into the trap of complacency once you have exited the early recovery period. As long as you continue to make recovery a priority, and stay connected with those in your support network – as you did while you were in treatment and early recovery – your chance of sustaining successful, long-term recovery greatly increases.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

Courts everywhere have mandated that secular, evidence-based addiction treatments, like SMART Recovery, must be offered to individuals as alternatives to 12-Step and other faith-based programs, if they so choose. Much of this is largely thanks to the tireless work of individuals like Sarah Levin.

Sarah is founder and principal of Secular Strategies, a firm specializing in defending the separation of church and state, advocating for religious freedom for all, and empowering nonreligious constituencies. A graduate of American University in Washington D.C., Sarah works on behalf of SMART Recovery on state government relations matters, under the direction of David Koss, SMART Recovery’s Director of Government Relations and current Board Member.

Check out this great interview by Luke Frazier, for our new show Insiders+ Access, made possible in part by the generous support of SMART Insiders+ participants.

Sarah Levin is featured in the podcast, Swimming Against the Legislative Tides

Additional information about the New York legislation bill

For more information on how you can join the SMART Insiders+ Program, go to: www.smartrecovery.org/insiders

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!