“. . . the individual, family and community are not separate; they are one. To injure one is to injure all; to heal one is to heal all. – from The Red Road to Wellbriety, 2002” – as quoted by William White, Recovery Rising

Perhaps the most important insight in recent recovery history is that recovery community, through collaborative effort leads to restoration not only in individual lives but supports healing across entire communities, in all their diversity. Recovery capital is a function of self and community agency. We saw that insight take form twenty years ago, highlighted in the writings of Bill White, Don Coyhis and many others. Bill wrote about recovery rising and community as the primary change agent of healing. Don wrote about incorporating native community methods into healing processes. Not narrowly defined peer service, but the capacity of community to heal itself. It works across America in modestly supported pockets. Developing recovery capital is fundamentally about resourcing and supporting diverse communities to address their own needs. This meets a lot of resistance.

We need to examine these headwinds if we are to keep moving forward. It is critical to take a hard look at how the recovery community gets sidelined and coopted in subtle or not so subtle ways. Head winds that create barriers to self and community agentry must be fixed if we are to get more Americans into wellness. These forces often stem from homeostasis, even as the state of things is woefully inadequate to the tasks at hand.

If we can reach a point where our voices are included in matters about us, our communities are strengthened, and we have real equity in the systems that serve us, headwinds can become tailwinds. To change, people and systems alike must come to terms with the impact of stigma on our recovery community. We must acknowledge that stigma of addiction and the discounting of persons with lived experiences is commonplace across all of our institutions. Stigma in the SUD realm often plays out across four interrelated dynamics:

- Cultural appropriation – The inappropriate or unacknowledged adoption of an element or elements of one culture or identity by members of another culture or identity. This is particularly true in respect to marginalized groups, which include the recovery community. Recovery initiatives not grounded in recovery are titled and run as such; treatment organizations rebrand services as recovery oriented for funding. Projects to collect our stories by outsiders are funded. Foundational elements of the recovery movement get appropriated when they become valuable. This extends to the very notion of recovery and all of its facets.

- Colonization – The action or process of settling among and establishing control over an indigenous people (in this case the recovery community). Control over what happens in the environment is delegated by entities in power to groups outside of the indigenous community to sustain control. This serves to undermine and inhibit the capacity of the inhabitants of recovery community to manage their own healing.

- – Healing methods and those permitted to provide such services shift away from the very recovery community who developed them. Barriers are erected to keep the marginalized group out in ways that the dominant group does not want or to prevent any shift of power to the marginalized group. Services become harder to provide. These barriers have the most severe and disparate impact on persons who are members of other marginalized groups, like BIPOC recovery communities.

- Cooptation – People from outside of recovery community organizations are placed in power over the role and function of recovery community groups to maintain the status quo. This serves to keep the recovery communities from developing a greater degree of agency over their own healing.

These are serious concerns not often spoken about in open dialogue out of very real risks of retribution but commonly discussed behind closed doors within the recovery community. Over the years, I have spoken to people around the nation in the recovery community who talk about how these dynamics play out. They include:

- Events or services initiated by the recovery community get taken over by treatment agencies or the government. We end up fighting to retain even window dressing levels of inclusion in our own projects.

- Pedagogy developed by us and for us get taken away and end up under the control of our bureaucracies, who then place barriers for us to access these very same methods of instruction. The process of learning and service provision begins to replicate the very challenges that they were developed to navigate around.

- Recovery communities are disparately resourced, instead academic, and large human service organizations get the lion share of resources. When funding is set up for us, recovery community groups are often pitted against each other for scraps. This creates further divisions that sustains an unhealthy homeostasis.

- Who has control over our stories matters! Our stories get clipped into other groups agendas. We get written out of our own history. Our stories must be handled in ethical ways. Communities who are written out of their own teachings cease to exist in a generation. Revisionist history replaces the authentic history.

Even the most well-intentioned policy makers often end up unintentionally reinforcing these dynamics. Stigma is that powerful and that entrenched. If you are in a position of authority over our communities and you see people asking a lot of hard questions or becoming upset by what you are doing, perhaps share some of the power and strive to understand it and seek remedy in collaborative ways to strengthen agentry. The more common reaction is to quash it. Shut it down and move the process forward to meet predetermined objectives.

Signs of affirming recovery community agentry:

- Systems that affirm our very right to define ourselves and keep in check ever-present tendencies to define and control us have a better opportunity to effectively strengthen recovery through collaborative action.

- Systems accountable to those of us they serve and open to this responsibility with a sensitivity to the most marginalized subgroups can augment our strengths, engender trust and lead to more effective outcomes.

- As Recovery Capital is a function of community and is not just and individual process, systems that ensure that resources get to the members of the community are telegraphing that they understand communities are best suited to affect their own healing. The opposite of paternalistic care, which is rooted in stigma.

Last year, I did a series of interviews with some of the pioneers of the New Advocacy Recovery Movement. One of the parts of the interview with Bev Haberle that resonated with me as fundamental in a recovery-oriented change processes is the centering of our efforts in community grounded ethics. During this interview with Bev, when I asked what she was most concerned about in respect to the future, she expressed a concern that we may end up falling backwards if not careful to pay attention to ethics grounded in the community served. She noted:

“I recall one of the Recovery Community Centers I was involved with and how much effort we put into building an authentic advisory group. People who served on this advisory group / vision team were charged with keeping us focused on the needs of the community and making sure everything we did was done with high ethical standards. They were charged with being stewards of quality recovery support services that meet the needs of the local Community being served. There was a lot of open discussion about what we were doing and we worked hard to make sure we stayed true to our community mission. They often spotted things the rest of us missed. People coming into our centers with what on the face of it looked like beneficial things but who had hidden agendas or self-dealing schemes. As a leader, I knew we needed them as our anchor to our mission.”

Well-functioning systems spend a lot of energy examining ethics and making sure that they run in adherence to good principles. Even the best-intentioned systems do unintentional harm, but the best of them actively work to minimize and fix those harms. In Pennsylvania, we have horrific examples of disparate treatment of the recovery community. It happens in other states as well. What harms one of us harms us all. I see recovering people leaving our field in droves because of the impact of moral injury, as I noted in this article in Treatment Magazine last May:

“Being in recovery makes many of us “those people” who end up getting disparate care. Every time I see it, I recognize it could be me getting disparate care and insurmountable barriers to accessing help. I could have ended up in a body bag instead of having a life. Every single day this very long week, I have spent time on the phone with people describing care denials of life-sustaining medical interventions under the lens of seeing addiction as a moral failing by licensed medical professionals, persons in long-term recovery who are being denied employment for decades-old legal charges and more. It is a normal week. It also hurts my soul.”

Disparate treatment creates systemic wounds that require healing. Healthy systems welcome tough dialogues and seek healing solutions to these wounds, dysfunctional systems shut down those discussions as too difficult and end up causing even deeper scars. What harms one of us harms us all. What heals one of us heals us all. These are tough subjects, but the work to heal these wounds can shift our headwinds to tailwinds and help heal whole communities. Ignoring these wounds deepen these harms and prevent collective healing. What kind of system of care do we want? The one I want to create deals with the tough stuff head on. If this was an easy process, we would have fixed it decades ago, it remains the challenge before us.

Many people have others in their lives that struggle with alcohol addiction – or struggle with addiction themselves. However, because of the stigma around addiction, help is often not received as those with addiction problems keep their struggles bottled up inside. They fear societal repercussions of admitting their problem and seeking help. They may not even know who they can confide in, or where they should begin looking for help.

Many people have others in their lives that struggle with alcohol addiction – or struggle with addiction themselves. However, because of the stigma around addiction, help is often not received as those with addiction problems keep their struggles bottled up inside. They fear societal repercussions of admitting their problem and seeking help. They may not even know who they can confide in, or where they should begin looking for help.

Alcohol Awareness Month, established by the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD), takes place every April with the goal of educating people about the dangers of alcohol abuse and reducing the stigma surrounding addiction and recovery, so that those most in need of help feel comfortable asking for it. If your loved one is struggling with alcohol abuse, or if you yourself have been struggling, Alcohol Awareness Month urges you to seek help, start important conversations, and be a support system for those around you who might be struggling.

If you find yourself asking “How can I participate in Alcohol Awareness Month?”, use these suggestions to get an idea of what the month is all about.

Have difficult conversations with loved ones who might be struggling with addiction.

If you’ve noticed that a loved one is relying on heavy drinking to cope with stress, sit them down and talk it out in a low-pressure, relaxed environment. Let them know you’re there for them without judgement or accusation. Offer to help them find treatment or Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings in their area. Be a steady, unwavering support system for your loved one when they need it most. This could be the conversation your loved one needs to serve as a catalyst for seeking help and treatment. Or, they may continue feeling like they’re not ready to get help. Persist in communicating with your loved one in a firm yet loving way, helping guide them to the right decision.

For a comprehensive list of nearby AA meetings by state and city, visit the official site at https://alcoholicsanonymous.com/

Change attitudes.

You might have certain preconceived notions related to alcohol use and those who suffer from addiction. Actively work to change these stereotypes and redirect your thinking in a more positive, helpful way.

There are countless books, essays, and online articles revolving around the subject of alcohol abuse and addiction. Put in the effort to help your loved one succeed and begin doing your own research – maybe even begin attending Al-Anon support groups, which are similar to AA meetings but held specifically for family members and loved ones close to those suffering from addiction.

For a comprehensive list of nearby Al-Anon meetings by state and city, visit https://findrecovery.com/alanon_meetings/

Work to change attitudes of those around you as well. For example, sit down with younger kids and talk openly about alcohol use in the hopes of changing their own attitudes and continuing to erase stigma. Discuss healthy coping mechanisms with them and emphasize that negative feelings and situations cannot be erased with alcohol use.

Throw a clean party!

Those dealing with alcohol addiction often feel pressured to drink in party settings with their peers, who may or may not also suffer from addiction. They might feel like it is impossible to have fun or be social without alcohol. As a support system to a loved one suffering from addiction, give them an opportunity to see how enjoyable an alcohol-free lifestyle can be. Host a gathering where drinking alcohol is explicitly prohibited. Serve other drinks like mocktails, club sodas, root beers, and any other fun concoctions.

Since beginning in 1987, Alcohol Awareness Month has made a concerted effort to save countless lives nationwide from alcohol-related deaths by making people more aware of alcohol abuse and encouraging them to spread the word and help others. Take the message of Alcohol Awareness Month and apply it throughout the entire year – be a light for others in need and spread hope!

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

SMART Recovery was proud to feature Dr. Nora Volkow, Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), as the inaugural presenter of the Jonathan Von Breton Memorial Lecture Series.

Her presentation was an eye-opening and informative Master Class in how NIDA-funded research programs and initiatives are yielding scientifically quantifiable results in addiction prevention, treatment, and after care. She touched on a broad range of topics including more progressive and pragmatic ways to help individuals with Opioid Use Disorders (OUDs) through adaptations in the judicial system, increased role of telemedicine, Naloxone overdose education kits, take-home Methadone protocols, safe injection sites, syringe service programs, and free Fentanyl test strips to combat the tens of millions of Fentanyl-laced street drugs flooding the United States every year. Dr. Volkow also shared data about the critical role that peer support programs play in intervention, addiction treatment and after-care, especially in the penal system, youth programs, and rural recovery settings.

SMART Recovery is proud to be a long-time supporter of these and similar strategies, reflected in our successful NIDA-Funded InsideOut Program: A SMART Recovery Correctional Program®, Teen & Young Adults Program, and the Fletcher Group Rural Centers of Excellence initiative to bring SMART Recovery mutual support meetings to rural recovery homes across America. Especially noteworthy was Dr. Volkow’s strongly-stated position on the need to overcome the stigma associated with addiction treatment so that more individuals feel empowered to get the help that they need, a position shared by SMART Recovery and reflected in our current Take on Addiction campaign.

Watch the presentation on our YouTube channel.

Click here to view the presentation slides.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

“I don’t even agree with myself 100% of the time” – me

It is a tongue in cheek self-quote. Cheap, but true and relevant to the piece. Perhaps you may even identify with it. Afterall, we all hold views that seem contrary or in conflict with each other. It is the essence of the human condition. What we understand evolves over time in a lifelong process.

Harnessing ways to improve our capacity to understand complex, multifaceted issues like addiction and recovery are vital to improving our outcomes. We need to evolve our thinking to do so. It would serve us well to bring people together to examine our assumptions in service of common goals. Strategies that move us forward and not pit us against each other as we also have a long history of enduring.

We have examples grounded in our own history of people come together to accomplish hard things. This is why it is vital to understand what has come before us, to examine strategies that worked, develop insight into why they worked and consider what may have been missed or done in ways we can learn from to effect improved strategies moving forward. We also have to consider how to use what we learn to overcome new challenges.

I have been reflecting on my own (evolving) views on the New Recovery Advocacy Movement. At the beginning of the era in the 90s, I was working in a publicly funded treatment program. The very same organization I found help at over a decade before in the mid 80’s. Filled with people who understood and lived within the culture of recovery. I place I felt understood and supported. Where I was greeted with a lot of positive regard and empathy by people who had walked similar paths to the one I was on. I had a lot of say over my own treatment, including duration, frequency of services and content of my sessions. The very things I later found myself trying to protect as administrative burden and staffing regulations that served as barriers to recovering people entering into the workforce multiplied. Reimbursement rates inconsistent with the tasks at hand that made it increasingly challenging to deliver the very services that saved my life years earlier.

By the late 90s, I was reading the writings of Bill White on recovery-oriented systems of care and running the program I had been served in years earlier. I liked a lot of what he said, but other things I did not appreciate at all. I thought he was unfair to treatment and the contributions that many of us in recovery were making. While I had mixed feelings about what he was saying, I applied the recovery principle of examining and exploring my own discomfort to see if I was missing something. Looking for and examining my own blind spots.

I recall reaching out to him during this era to explore what he was writing about. I was pleasantly surprised when he wrote back. We had several great conversations. I felt heard. I better understood what he was writing about. I started to see more clearly what he was saying about the erosion of recovery in our systems of care. I increasingly agreed with his views as I grew to understand them. I suspect that such gradual shifting views through his writings and polite and respectful dialogue about these concepts helped change a lot of views in that era. We overcame the forces of division by embracing our recovery values.

I gradually came to understand that he was most critical of acute treatment models that were not oriented towards long-term recovery. The subtle erosion of focus on recovery in our care systems. An SUD workforce that has fewer and fewer people in it who had lived experience with recovery. Too many workers who had no frame of reference of what the people they were serving experienced in their respective recovery journeys. A system that increasingly failed to deliver the care and support people needed to heal. Thoughts that resonated with a lot of our community nationally. People coalesced around the emerging concepts to address these concerns.

His writings influenced and helped shift my views, but I had also been open to understanding his perspectives where they challenged my own views. I was open to examining my own confirmation bias. It got me to thinking about writing as a medium to explore ideas. It is a vital medium. Is a written article intended to be something etched in stone so that every word is to be considered as unending truth? Do we use writing to evolve ideas, to develop deeper insights and to find common ground, or to cancel out seemingly oppositional views and those who hold those perspectives?

Few mediums allow us to explore ideas like the written word. I am also not sure anything else is as effective. But it takes time and energy to write and to read. One facet of how it is changing comes from social media, which has changed the way we write and think. Social media uses algorithms that feed into our own confirmation biases and allow us to avoid different ways of thinking or uncomfortable truths. It can magnify our worst traits. This article notes how rude behavior spreads like the flu on social media, a breeding ground for negative behavior. It can be used as a powerful bludgeon to shut down discourse and stifle thought and expression which unfolds in a Spiral of Silence. Dynamics toxic to positive change. How do we overcome these formidable barriers that make it harder to hold common ground? How do we make sure we spend enough time with not entirely likeminded people who are civil so we can examine our own views more deeply?

All communication is imperfect, every medium has flaws as do the sender and receiver. Yet most of our shining moments in world history center on times we overcame these challenges to champion greater truths. Our finest moments as a species relate to overcoming our differences. Yet, a lot of forces push against the dynamics of positive change. A good book on the topic is Them, Why We Hate Each Other–and How to Heal by Ben Sasse. My takeaway line from his book is that we no longer unite on things we agree on, we come together focused on things we hate. These two things have very different energies. Hate is a very destructive force. It seems far too often these days that hate and division are winning. We cannot let it. We cannot let darkness to prevail over light.

We also have to start by acknowledging the inherent flaws of our communication mediums and our own powers of perception. I did not fully appreciate what Bill White was saying in those early days because I was working as hard as I could to accomplish similar goals inside the system he was being critical of. I initially focused on his criticisms and what I thought they meant rather than what he was trying to say and our common ground. I could have reflexively rejected everything. To be lazy and reject his valid points where they challenged my beliefs. Instead, I chose to explore what he was saying with as open a mind as possible. Others did too.

We must examine our own flaws and blind spots in order to understand our common ground. Challenging our own flawed perception is a fundamental process in recovery. We do this to overcome addiction and can apply it in other ways as well. It is one of our superpowers.

Some thoughts emerge in respect to what we do next and things we should remain mindful of:

- All communicators are imperfect despite our best efforts.

- All communication mediums are imperfect. We need to factor this into how we receive information.

- All receivers of information are imperfect. We all have blind spots and biases.

When we consider those truths, we may:

- Question our own reactions to what we see and hear as we are imperfect receivers of information. Doing so can offer clues in our own biases and assumptions and help us see the truths in other perspectives.

- We collectively benefit when we evolve our ideas over time to identify our common ground.

- We cannot build anything up in the long run by diminishing each other.

- We have a lot to lose if we do not figure out ways to find and hold common ground. Not just in the recovery movement, but as a society in general.

Some open questions:

- How do we overcome the barriers created through social media and reduced social connection?

- What are our responsibilities to those who fought hard for us to get here and to those depending on us to carry this work to the next generation?

- What are our agreements on how we express and receive ideas across our ideological camps?

- What do we stand to lose if we simply maintain the status quo?

We have some decisions to make about what we do and how we do it. What we do will determine how we will:

- Strengthen long term recovery facilitated by our diverse communities for our diverse communities.

- Ensure that our voices are included in meaningful ways in all matters that impact us.

- Develop future leaders and expand recovery to every American with a substance use issue.

We have a big agenda. Are we going to be big enough to come together to serve it effectively? History shows us we can when we decide to do so, together. The question is will we?

The answer to how we do so starts with each one of us and the effort we take to understand and incorporate our varying views into a broad recovery plank.

If effectively addressing addiction was easy and straightforward, we would have done so already. In reality, it is a multifaceted condition that defies narrow solutions. There are complex genetic and environmental factors that lend themselves more to a continuum of use, problematic use and addiction that is not consistent with either / or check box definitions we tend to use. This is why we still grapple with how to define and address addiction over so many decades. Oversimplifying the continuum of substance use dependence and its consequences remain a significant factor in why we have not developed society wide support.

We have had our successes. Twenty years ago, the recovery community focused on long term, multiple pathway recovery strategies in order to expand recovery efforts across our entire society. Thank you, SAMHSA for spearheading it! We worked to shift efforts from acute care treatment to longer term community-based recovery-oriented efforts. It resonated because it was exactly what was needed at the time. Despite our diversity as a recovery community, we have often found common ground and goals in civil, solution focused discussions. This is an example of a strategy we did collaboratively with many groups working together. Our efforts paid dividends. Developing services that were widely supported by highlighting the value of recovery rather than focus on the pathology was key. But another facet of what worked is that we did so without sugar coating the devastation of addiction within our families and our communities.

We should not ignore that when a severe substance use disorder (SUD) remains unaddressed, it ravages our entire society. In Portugal they have what they call Dissuasion Commissions that can pressure people to seek help (which is on demand, another thing we do not have) for good reason. They got rid of open-air drug markets. Portugal decriminalizing drugs but did not de-penalize drug use, a distinction I often hear missed. We should pay attention, even as our society is very different than Portugal. We seem to be only focusing on part of their solution. It is what we seem to do best.

How do we provide more nuanced messaging to support helping persons who experience problematic drug use with dignity and respect, while balancing the unique risks of drug use and addiction to our society? I recently ran across an article that Dr Keith Humphreys wrote that seems relevant to how we frame and address addiction as a condition, “how to Deliver a More Persuasive Message Regarding Addiction as a Medical Disorder.” I think it holds some answers.

As Dr. Humphreys notes, while addiction shares many features with other medical conditions like diabetes and heart disease, unlike those conditions, addiction has a high level of negative externalities. This impacts how decent and reasonable people respond to persons with addictive disorders. Given the impact of addiction on our society, we should expect that people have very negative views about us. As he says, it is common decency to note that there are victims of our drug use and that focusing on helping people like me recover is by no means an attempt to minimize that damage.

Having observed and experienced abysmal attitudes even in our medical care communities as noted last year in “take the drug addicts out to the hospital parking lot and shoot them,” it is evident that as a society we still hold very high levels of stigma against the entire population of people with SUDs. My organizations collaborative work with Elevyst and RIWI on an initial survey of perceived stigma in the United States, shows this in stark relief. We also found a whole lot of common ground, significantly more than any differences of views we have. It is a very productive process. That stigma is our biggest barrier is a consensus statement. We must improve public perceptions about us.

But the negative perceptions about us are understandable on many levels. Addicted persons like me (not in recovery) drive while impaired and end up killing people as a result. We can cause severe trauma in families and even become violent under the influence of drugs like alcohol and methamphetamine. We can pose risks to society that require law enforcement interventions. We should focus on ways that reduce the chaos and danger on our streets, keep people alive, and address violence concerns associated with addiction without reflexively throwing people who use drugs into cages. We should keep our eye on the goals of long-term recovery, the only true way to reduce the number of addicted people in our communities. We seem to be losing that focus, and I am alarmed.

Our big problem is that we tend to view addiction as either a medical condition or one in which we simply incarcerate everybody who has it. The latter is clearly not the solution. The reality it is a medical condition but also a public safety issue. It erodes all of our institutions. Turning it into an either / or problem oversimplifies it. Dr Humphreys reminds us that it is important to acknowledge these harms to society even as we call for compassion and develop more effective ways to improve public perception about us. Addiction is not diabetes or heart disease in respect to what it does to our society. Nuanced policies here would make sense. To get there we need to figure out ways to message the value of helping people recovery and also acknowledge the risk to society if we do not support more people into recovery.

We must develop accurate messaging if we are to improve public perceptions related to substance use and addiction in America. We also need to acknowledge the devastation our society is experiencing, including a 24% increase in alcohol related fatalities on our highways, overdose deaths that continue to move in the wrong direction and a likelihood of an increase in violent crime due to the increased prevalence of methamphetamine use on our streets. We risk seeing the balance shift to law-and-order centered solutions in the near future that throws the most marginalized of our brothers and sisters in prison cells in a wholesale process as society tires of the damage we are capable of. The pendulum always swings. That would perhaps be an even more devastating than our climbing death rate.

My own experience with addiction, recovery, and work for decades highlights the dichotomy of addiction. The vast majority of people who become addicted are great people. We then do a lot of damage to ourselves and those around us. We can be really destructive. I would not now consider doing a lot of the things I did in active addiction. I know that I am not alone in this. This is because of the way that addiction impacts both executive function and the limbic system. We know that persons who are addicted are not fully in control of their faculties. This is why we cause such devastation in active addition. Properly framing addiction by acknowledging the damage that our communities experience as well as the cycle of trauma that a lot of addiction stems from while focusing on developing and sustaining public support for recovery is critically important to strengthening public support for our efforts. We should consider that:

- People who use drugs problematically deserve our compassion and empathy.

- Engaging persons who are using with the stance that they deserve respectful care will more likely lead to them seeking help and support and achieving wellness.

- People experiencing addiction can at times put their own lives and the lives of those around them at risk. There are very real public safety concerns associated with substance misuse.

- People with severe SUDs may also become involved in illegal or even violent behavior while in the throes of addiction. Such conduct is not indicative of who we are in recovery.

- Helping someone with a substance use disorder recover greatly reduces the risk of dangerous or inappropriate conduct and is ultimately the most effective way to reduce the number of addicted people across our nation.

- Given the proper care and support recovery leads to recovery, which is the probable outcome for persons with a substance use disorder. Focusing resources on this goal will expand the number of persons in recovery, improve the health and safety of our overall community and save a lot of resources in the long run.

Our own history of addiction treatment and recovery provides a note of caution. The history of recovery in America is not linear, just like all other facets of history. Bill White showed us that with his seminal work Slaying the Dragon. There is a “two steps” forward, one (two or even three) step(s) backward dance through the years. We tend to move from compassion and support to punitive responses to addiction over the long arc of time and then eventually back towards compassion and support. This occurs for a lot of reasons, one of which is how we oversimplify our messaging.

One thing that is illustrative of the problem is how we have disingenuously portrayed drug use. It has been devastating. Anyone who has watched reefer madness and has experience with cannabis would sense that the propaganda film dramatically overstates the risks of this drug. Like a lot of kids, I disregarded all the real risks as a result. I could tell what this film was showing was not true, so I ignored all the stated risks I heard in health class. I smoked pot and laughed through the movie. Now it is portrayed as having almost no risk, which is also not true. We will pay for that too.

In a similar way, normalizing destructive drug use on our streets will strike a large portion of our nation as an improper response they will ultimately not support. At least from my perspective. Understating the risks to society of normalizing problematic drug use may well lead to a backlash from the American public who suffer the collateral damage. Pretending that addiction is just like any other medical disorder and that persons who experience it may not pose additional negative externalities is disingenuous. Sugar coating the impact of people who use drugs on society is a very risky strategy. The truth is that people who are addicted deserve compassion and that we also present very real public safety risks. We do a lot of damage as a result of addiction. They should be considered hand in hand, not as either / or. We have to acknowledge the complexities of our challenges to develop effective strategies. Starting there may help us get to the point where we can provide more pervasive arguments for supporting both harm reduction and recovery efforts, which can and do work hand in hand to support the health and welfare of our communities.

Just my two cents on a medical condition not just like the other ones.

Just because Tim Burton had a previous career in the steel industry doesn’t mean he’s hard-headed. In fact, Tim is open-minded and willing to learn, which has led him to where he is today: a Volunteer Support Specialist (VSS) for SMART.

He felt a calling to work in the addiction and recovery field after working in a hospital, and it became a pursuit a couple of years ago. “I found a job with a Recovery organization working in KY counties where [Opioid] overdose rates were the highest. From there I discovered SMART and became a facilitator.”

As a VSS, Tim loves hearing from volunteers who are excited to be starting out as meeting facilitators as well as seasoned facilitators sharing their passion for SMART. He helps all those who need it.

Here are Tim’s responses to the Take 5 Spotlight questions:

- Are there tasks you perform regularly during your workday? Right now, it’s all about the audit we are doing to clarify meeting status across the US, but in my spare time it’s about learning all the other job functions—there is a lot to learn.

- What are a couple of the ways you interact and coordinate your job with other national office staff? The Volunteer Department touches everything else in SMART Recovery, it’s really the backbone of the whole organization.

- What is one of the ways that you think you personally make a difference at SMART? My background is so diverse that I hope to be a utility player that makes a difference. Put me in coach, I’m ready to play!

- What is your message to all those dedicated SMART volunteers across the country? Discouragement is your enemy and don’t try and shoulder it alone. Call me!

- What kinds of things are you interested in outside of work? Any hobbies? Just about any human power sport. I’ve backpacked over 200 miles of the Appalachian Trail since 2020, my wife and I love kayaking, and cycling is my lifelong passion. Sunday morning finds me in church somewhere.

Whether you find Tim on the trail, in the water, on wheels, or sitting reflectively, you’re sure to understand one thing: he loves SMART and helping people. A powerful combination and a great contribution to SMART’s Volunteer Support Department.

Learn more about the Take 5 Spotlight series and see others who have been profiled.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

For Alena Kuplinski, a SMART employee who splits her work responsibilities between the Call Center and Volunteer Headquarters (VHQ), her success at SMART came by way of Poland. As in the country of.

Alena lived in Poland for five years and says it set her up for success in dealing with all kinds of people, “I was lucky enough to meet and work with people from all around the world, [I learned] to communicate effectively across language barriers and cultural differences.” This meant she became a great listener & communicator, and that’s essential for the work she does.

Her VHQ activities include keeping track of new meetings, making necessary changes to existing ones, registering volunteers, and anything else that needs done. In the Call Center she handles the broad array of inquiries that flood the SMART phones.

One specific connection she has to SMART is through her father, who has been a participant in meetings trained facilitator, and is now Regional Coordinator for Nevada. This provided a close-up view of SMART’s value, “Seeing how much SMART helped him really made me have a lot of passion for the organization as I have witnessed firsthand just how much it can change lives.”

Here are Alena’s responses to the Take 5 Spotlight questions:

- Are there tasks you perform regularly during your workday? The first and foremost task is taking care of meeting changes to make sure our list is up to date and accurate, so that those wishing to attend a meeting are getting the correct information. Another task I do regularly is answering our Contact Us emails in our VolunteerHQ inbox. And of course, answering phones!

- What are a couple of the ways you interact and coordinate your job with other national office staff? Those of us in the National Office make effective communication a top priority. We keep in touch via Zoom both through messages and calls, as well as emails, to make sure that we are helping everyone that needs help.

- What is one of the ways that you think you personally make a difference at SMART? Between my work in the Call Center and VolunteerHQ I spend a lot of time interacting with the participants of our meetings as well as our facilitators. I feel like this gives me a special opportunity to help people in all aspects of their recovery and involvement with SMART.

- What is your message to all those dedicated SMART volunteers across the country? I am endlessly impressed by the dedication of our volunteers and without them SMART would not be what it is. Thank you for all of your hard work!

- What kinds of things are you interested in outside of work? Any hobbies? I’m a huge music lover and spend a lot of time listening to music, attending concerts, and practicing bass. I also enjoy reading, writing, playing video games, traveling, and cooking.

The music that SMART Recovery hears when it comes to Alena Kuplinski is a fluid melody of listening, responding, and helping. That’s the kind of song that makes SMART function like a well-tuned orchestra.

Learn more about the Take 5 Spotlight series and see others who have been profiled.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

The DrugWise Daily newsletter noted the passing of Sara McGrail.

I never met Ms. McGrail and I didn’t follow her work, but her name rang a bell. I knew I’d interacted with her years ago but couldn’t remember the details.

It turns out we interacted around some posts related to harm reduction in 2008.

I had posted a response to something she wrote, she respectfully and thoughtfully responded. A couple of months later, we had a similar exchange that resulted in my conceptualization of recovery-oriented harm reduction.

This was an outcome of her meaningful engagement in the face of our disagreements, and her challenging, vigorous, substantive, and good faith arguments.

We saw things differently, but her questions, assertions of her values, and her prodding challenged me to examine my convictions and made me more thoughtful.

As I said, my knowledge of her and interaction with her was limited, and I don’t know if it was typical of her. Whatever the case, I am grateful to her for challenging me to think more deeply about the intersection of harm reduction and recovery.

What is recovery-oriented harm reduction?

Recovery-oriented harm reduction (ROHR) seeks to address the historical failings of both abstinence-oriented treatment and harm reduction services. ROHR views recovery as the ideal outcome for any person with addiction and uses recovery (for addicts only) as an organizing and unifying construct for treatment and harm reduction services. Admittedly, these judgments of the historic failings are my own and represent the perspective of a Midwestern U.S. recovery-oriented treatment provider.

Addiction is an illness. The defining characteristic of the disease of addiction is diminished and/or loss of control related to their substance use.

Drug use in addiction is not freely chosen. Because the disease of addiction affects the ability to choose, drug use by people with addiction should not be viewed as a lifestyle choice or manifestation of free will to be protected. It is not an expression of personal liberty, it is a symptom of an illness and indicates compromised personal agency.

All drug use is not addiction. There is a broad spectrum of alcohol and other drug use. Addiction is at the extreme of the problematic end of that spectrum. We should not presume that the principles that apply to the problem of addiction are applicable to other AOD use.

ROHR is committed to improving the well-being of all people with addiction. ROHR services are not contingent on recovery status, current AOD use, motivation, or goals. Further, their dignity, respect, and concern for their rights are important are not contingent on any of these factors.

An emphasis on client choice—no coercion. While addiction indicates an impaired ability to make choices about AOD use, service providers should not engage in coercive tactics to engage clients in services. Service engagement should be voluntary. Where other systems (legal, professional, child protection, etc.) use coercive pressure, service providers should be cautious that they do not participate in the disenfranchisement or stigmatization of people with addiction.

For those with addiction, full recovery is the ideal outcome. People with addiction, the systems that work with them, and the people around them often begin to lower expectations for recovery. In some cases, this arises in the context of inadequate resources. In others, it stems from working in systems that never offer an opportunity to witness recovery. Whatever the reason, maintaining a vision of full recovery as the ideal outcome is critical. Just as we would for any other treatable chronic illness.

The concept of recovery can be inclusive — it can include partial, serial, etc. While this series argues for a distinction between recovery and harm reduction, Bill White has described paths that can be considered precursors (precovery) to full recovery.

Recovery is possible for any person with addiction. ROHR refuses cultural, institutional, or professional pressures to treat any sub-population as incapable of recovery. ROHR recognizes the humbling experiential wisdom that many recovering people once had an abysmal clinical prognosis.

All services should communicate hope for recovery. ROHR recognizes that hope-based interventions are essential for enhancing motivation to recover and for developing community-based recovery capital. Practitioners can maintain a nonjudgmental and warm approach with active AOD use while also conveying hope for recovery. All ROHR services should inventory the signals they send to individuals and the community. As Scott Kellogg says, “at some point, you need to help build a life after you’ve saved one.”

Incremental and radical change should be supported and affirmed. As the concepts of gradualism and precovery indicate, recovery often begins with small incremental steps. These steps should not be dismissed or judged as inadequate. They should be supported and possibly even celebrated and they should never be treated as an endpoint. Likewise, radical change should not be dismissed as unrealistic or unsustainable pathology.

ROHR looks beyond the individual and public health when attempting to reduce harm. ROHR wrestles with whether public health is being protected at the expense of people with addiction, whether harm is being sustained to families and communities, and whether an intervention has implications for recovery landscapes.

ROHR should aggressively address counter-transference. ROHR recognizes a history of providers imposing their own recovery path on clients while others enjoy vicarious nonconformity or transgression through clients. These tendencies should be openly discussed and addressed during training and ongoing supervision.

ROHR refuses to be a counterforce to recovery. ROHR seeks to be a bridge to recovery and lower thresholds to recovery rather than position itself as a counterforce to recovery. Recognizing that addiction/recovery has become a front in culture wars, ROHR seeks to address barriers while also being sensitive to the barriers that can be created in this context. When ROHR seeks to question the status quo, it is especially wary of attempts to differentiate from recovery that deploy strawmen, recognizing that this rhetoric is harmful to recovering communities and, therefore, to their clients’ chances of achieving stable recovery.

ROHR sees harm reduction as a means to an end. ROHR views harm reduction as strategies, interventions, and ideas to reduce harm. As such, it is wary of harm reduction as a philosophy or ideology, which sets the stage for seeing harm reduction as an end unto itself. Back to Scott Kellogg’s point, “at some point, you need to help build a life after you’ve saved one.” The end we seek is recovery, or restoration, or flourishing. Seeing harm reduction as a philosophy or ideology risks viewing it as “the thing” rather than “the thing that gets us to the thing.”

Codependent is a word that is thrown around rather loosely, but what does it really mean to be codependent? By definition a codependent person is one who has let another person’s behavior affect him or her and who is obsessed with controlling that person’s behavior. As you might imagine most people are not fond of this definition and do not want to see themselves as either controlling or obsessed. It can be helpful to substitute the words concerned for obsessed and helping for controlling, as those words tend to be more palatable to most.

Codependent is a word that is thrown around rather loosely, but what does it really mean to be codependent? By definition a codependent person is one who has let another person’s behavior affect him or her and who is obsessed with controlling that person’s behavior. As you might imagine most people are not fond of this definition and do not want to see themselves as either controlling or obsessed. It can be helpful to substitute the words concerned for obsessed and helping for controlling, as those words tend to be more palatable to most.

The reality is the only way someone suffering from substance use disorder can continue their addiction is if someone else is cleaning up the wreckage of it. In its truest form codependency is obsessive ‘helping”, doing things for another adult that they can and should be doing for themselves.

While it is healthy to feel concern for someone we love, codependency uses this concern to justify boundary violations as attempts to “help” the person we love. The only way we feel better is to make the substance user feel better by trying to fix their problems. We pay their bills, take care of their legal issues, cancel our plans in order to meet their needs, lie for them, and the list goes on. As long as we continue to rescue the substance user from the consequences of drinking and using, that person will use. It’s as simple as that.

Signs of codependency include:

- Offering advice to others whether it is asked for or not.

- Taking everything personally

- Lying or making excuses for another person’s behavior

- Using manipulation, shame, or guilt to control another person’s behavior

- Feeling responsible for other people’s problems

- Expecting other’s to respond a certain way

- Feeling like a victim

- Fearing rejection

- Feeling used and underappreciated

- Confusing being loved with being needed

In our society, codependency can be as deceptive as addiction. It hides behind the guise of helpfulness, “doing the right thing”, taking one for the team, or being a loving parent/spouse/child/partner/friend. It is a way of avoiding our true feelings by instead focusing on managing our external world. Codependent people often lose sight of where they end and other people begin. The boundaries are blurred or nonexistent.

If you are in a relationship with someone struggling with a substance use disorder, it is natural to experience a desire to help. It is tempting to believe your efforts to help your loved one will stop them from using. This is simply not true. The truth is focusing on your own recovery, finding peace and healing for yourself is the greatest gift you can give the people in your life. You’re worth it!

Written by:

Kelly S. Scaggs, LCSW, LCAS, CCS, MAC, ICAADC

CLINICAL DIRECTOR, Fellowship Hall

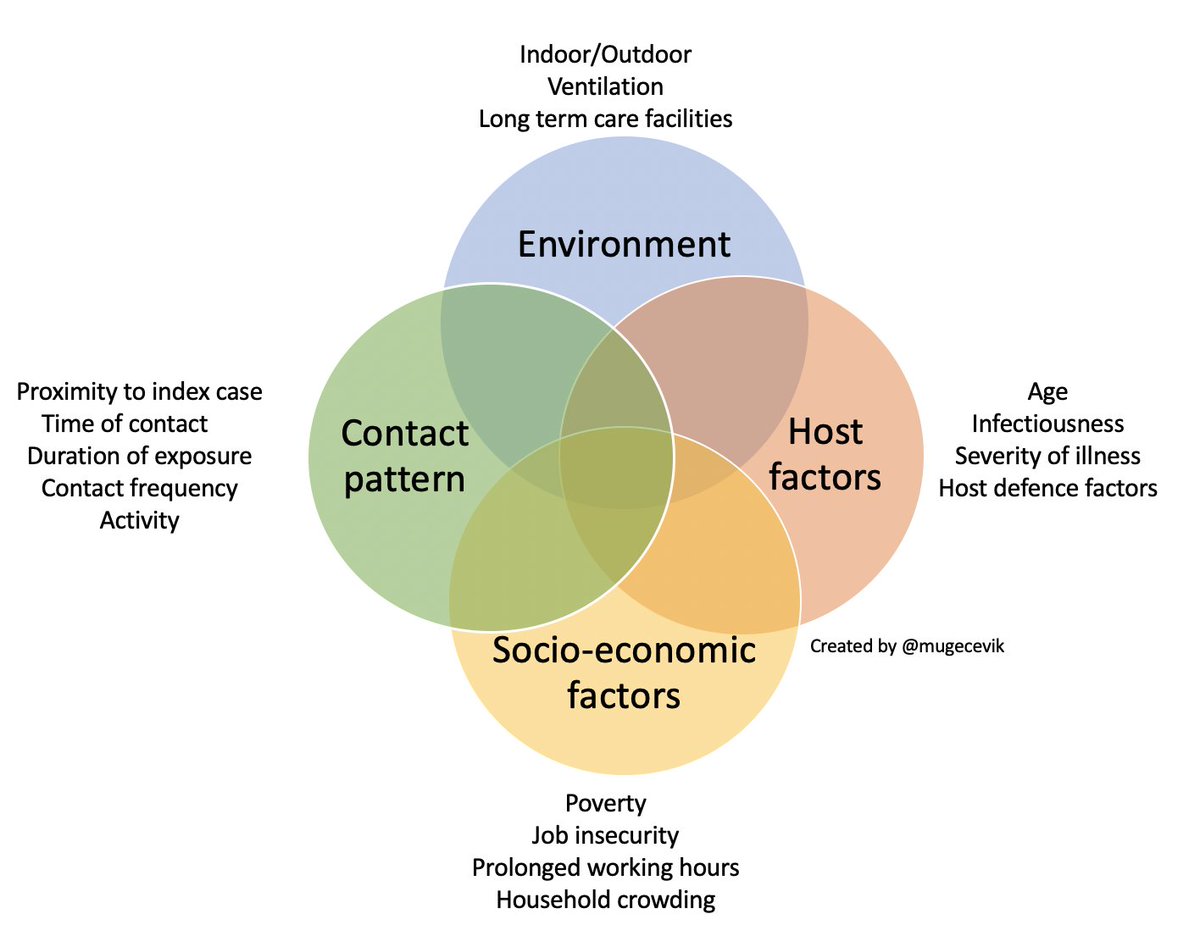

Tweeted by Muge Cevik on September 21, 2020

One argument against the disease model of addiction is that it advances a narrow medical model at the expense of recognizing social and environmental epidemiological considerations, as well as social and environmental interventions.

This image does a good job demonstrating that calling something a disease often should not necessitate a narrow medical approach. The graphic below focuses only on factors influencing transmission. Obviously, environmental and socio-economic factors don’t cause COVID, but they do influence risk, and that reality doesn’t make COVID any less of a disease.

I imagine a similar graphic could be made to represent the treatment and management of COVID that would include medical treatments as well as other factors and strategies (environmental, social, psychological, spiritual, etc) that influence access, engagement, compliance, response to treatment, and the pace stability of the patient’s recovery.

The import of those “nonmedical” dimensions only grows when we’re looking at chronic diseases that require management because there are no cures.