Two years ago, I started talking about the likelihood of the pandemic related isolation and turmoil leading to dramatic increases in substance misuse. I termed it an addiction tsunami, others made similar comparisons. The analogy is holding. COVID was the precipitating earthquake. The water is now beginning to rise and envelope a fragile service infrastructure teetering on collapse. It is probable that we are seeing only the initial ripples of this tidal surge.

We have been long vulnerable to the kinds of shocks and traumas we are now experiencing. The COVID-19 pandemic was like an extraordinarily powerful earthquake. Hundreds of thousands have died, and our behavioral health and medical care infrastructure has been severely damaged by the shocks. Our medical care professionals and first responders are particularly vulnerable to substance misuse as they are exposed to long term trauma. We are also ill prepared for this because of deep underlying stigma in these professions. All this before the water started to creep up.

We are woefully ill prepared for what is happening, and what we have focused on has generally been interventions not broadly focused enough to meet the needs of our diverse communities. We have a long-term addiction epidemic decades in the making. Unfortunately, in the last decade it has been narrowly framed as an opioid epidemic. This has had extremely negative and long-term consequences and hobbled our capacity to respond effectively.

We had largely ignored the steady increase in alcohol related deaths (which doubled between 1999 and 2017). A significant facet of the crisis. Instead, we have long focused on overdose deaths. Overdose deaths are a metric that policymakers find appealing because it is easily measurable. It is important to point out that such a narrow focus results in us failing to address the complexity of addiction. We end up ignoring the myriad of ways that addiction kills beyond overdose. We fail to address critical issues such as concomitant benzodiazepine use with opioids which according to NIDA is associated with one in three overdoses. We miss wider solutions by too narrowly conceptualizing the problem.

Consider how street drug use patterns are increasingly complex. As noted above, most persons addicted to opioids are using multiple drugs. This study published in Molecular Psychiatry found that more than 90% of individuals with OUD used more than two other substances within the same year, and over 25% had at least two other substance use disorders along with OUD. Addressing opioid addiction in isolation from other drug use is unhelpful at best, and like the concept of the war on drugs will ultimately be judged as a poor way to frame what actually is occurring. We put on horse blinders and fail to address the full scope of the problem we face, and the water continues to rise.

These complexities include drugs like xylazine, which “gives legs” to a high from any opioid through a synergistic effect. The combination of powerful opioids with this powerful non-opiate sedative is creating a medical and addiction care nightmare. We simply do not have the infrastructure available to effectively address these needs. These patients require intensive medical care provided in close coordination with intensive addiction treatment for extended periods of time. We do not have the capacity in our public service system for these patients. We have been caught flatfooted, dealing with a type of drug use adaptation that was entirely predictable. The water gets deeper.

Some of what we are seeing:

- The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use – Drug overdose deaths have sharply increased – largely due to fentanyl – and after a brief period of decline, suicide deaths are once again on the rise. These negative mental health and substance use outcomes have disproportionately affected communities of color and youth.

Alcohol-related deaths soared 25.5% in 2020. During the two decades prior to the pandemic, alcohol-related deaths increased around 2.2% per year. In 2021 alcohol related deaths saw an increase of 9.9% over 2020. Overall, alcohol played a role in 3 out of 100 (3.1%) deaths in the United States in 2021.

Like a tsunami, the longer we wait to respond, the more devastating the consequences will be and the harder it will become to get people into recovery. Like a tsunami, increases in drug and alcohol use across society will lead to a long-term surge in addiction. It will result in an increase in addiction for those most vulnerable to it as a result of things like genetics and exposure to trauma. Boredom, lack of purpose and loneliness may also be significant contributing issues. These upstream causative factors need to be addressed even as we try and pull people out of the water.

Surging water in a tsunami overruns the low ground and weak spots. Our public care SUD workforce and infrastructure in that low ground that is being inundated. It is particularly vulnerable because the type of long-term investment it requires to remain viable is not where resources have historically been invested. We have had a workforce crisis over the course of my decades in the field and we kept pushing off the solutions. Crisis fails to describe what we now face.

This will play out in time as measured in decades. It comes at a time when our service infrastructure and workforce were already in bad shape. It is highly probable that addiction related deaths over time will eclipse the direct loss of life from the pandemic by several multitudes. We are losing treatment and recovery support centers and care infrastructure at the very moment we need to be fortifying them and preparing for the increases in demand.

While significant amounts of new dollars from the opioid settlements will go to needed pharmaceutical treatments for opioids, people require comprehensive care and support beyond medication only remedies. Money had not flowed to the rest of the care infrastructure in similar ways as it has to MAT. Federal opioid crisis initiatives focused on infusing short term dollars to the states targeted on opioids that did little to address the long-term needs of the care system. These were “spend quickly or lose” dollars, not long-term investment. Money went to where it could be spent fast and far too often not to where it was needed most. In defense of our allocation systems, they are not really designed or resourced to do what we need done, so quick money was better than no money, which was the other door.

Single drug focused interventions and short-term harm reduction efforts that do not lead to comprehensive treatment and recovery will not get us to the safety of high ground. If we were serious as a nation in addressing SUDs, we would need to conceptualize addiction needs in America much like we do cancer, with a myriad of interventions, services and supports over the long term that can be individualized to the needs of the individuals, families and communities served. Long term remission is the standard of care for cancer. We do not think in those terms about addition. We should.

This would need to include:

- Building an SUD service infrastructure that is on the scale of the need for these services in America. The one we have typically does not even provide people with the minimum dose of effective care for patients with average needs.

- Developing a sustainable and properly resourced SUD service system workforce.

- Establishing a recovery-oriented system of care that meets the long-term needs of the diverse communities served. This would require the authentic representation of communities of recovery in the design, implementation, facilitation, and evaluation of programming at all strata, from federal, state, regional to the local community levels.

Recently, the Governor of California deployed the National Guard in the tenderloin district of San Francisco to address open air drug dealing. It is driving away business and making living in the city untenable. Those who can afford to leave it are heading for the hills. This is one major city in one major state, yet these dynamics are playing out across America. The truth is that “those people” are quite often “our people.” Our neighbors, our friends, our family members. We are not even close to taking this emerging crisis as seriously as we should. Considering just opioids and not the impact of other illegal drugs or alcohol, in 2022, the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee (JEC) found that the opioid epidemic cost the United States nearly $1.5 trillion in 2020, or 7 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), an increase of about one-third since the cost was last measured in 2017.

This is our leading domestic challenge in the United States, and conditions are worsening. What would we do if this was any other issue beyond the highly stigmatized condition that it is? When will we start doing those things?

The water is rising around us while we consider these questions.

By Stefan Neff, SMART Facilitator.

My therapist shared a great tool with me called an Urge Jar which is a simple yet effective technique that can help you break bad habits or form new ones. It works by creating a physical or virtual jar to hold your urges or cravings at bay. This technique has gotten me out of many sticky jams in the past.

The idea behind Urge Jar is that instead of giving in to your urge or craving, you acknowledge it and pull an activity from the jar even if you don’t feel like it. This allows you to take a moment to reflect on your actions and the reasons behind them. It also helps you to build self-control and discipline.

To create your Urge Jar, follow these steps:

1. Choose a container: You can use any container you like, such as a jar, a box, or a pouch. You can also create a virtual jar by using an app or a note-taking tool.

2. Label the container: Write “Urge Jar” or something similar on the container to remind yourself of its purpose.

3. Identify your triggers: Think about the situations or emotions that trigger your urges or cravings. This could be stress, anxiety, boredom, or social pressure.

4. Decide on a strategy: Determine how you will use the Urge Jar. For example, you could write down 30-50 activities and add them to your jar for every time you have an urge, and place it in the jar. Activity examples: clean the dishes, do your laundry, go for a walk or walk the dog, yes even clean the toilet, wash the windows, whatever you can do to distract yourself from your Urges and Cravings.

5. Use the jar: Whenever you feel an urge or craving, take a moment to acknowledge it and then pull at random one of your activities from the jar. You can also use the jar to track your progress and celebrate your successes.

Your Urge Jar can be used for a variety of habits, such as drinking, smoking, drugging, overeating, or procrastinating. It can also be used to form new habits, such as exercise or mindful meditation.

The key to the success of your Urge Jar is consistency. You need to use the jar every time you feel an urge or craving, even if you give in to it. Over time, you will build the self-control and discipline needed to break your bad habits and form healthy new ones.

In conclusion, your Urge Jar is a simple and effective technique that can help you break bad habits and form new ones. By acknowledging your urges and cravings and replacing them with a new activity from the jar, you can build self-control and discipline. Try it out for yourself and see how it can help you achieve your desired recovery goals.

Now it’s time to make your list of activities to fill your Urge Jar to the rim.

JAMA published new research on buprenorphine initiation and retention and the findings are disappointing.

The study looked at a database of retail pharmacy records from 2016 to 2022 that includes 92% of all retail pharmacies. (93, 713, 163 prescriptions)

If I understand correctly, this excludes buprenorphine dispensed in emergency settings. Those patients would only be included if they followed up and filled a prescription at a pharmacy. Medication dispensed in emergency settings is usually limited to a few days and would presumably have the lowest retention rates. The exclusion of those emergency prescriptions should tell us only about people who took the steps of going to a pharmacy and filling a prescription.

Initiating buprenorphine was defined as a prescription for a patient without a filled buprenorphine prescription in the last 180 days.

Retention was defined as continuous buprenorphine prescriptions filled over 180 days without any gaps of more than 7 days.

What did they find? [emphasis mine]

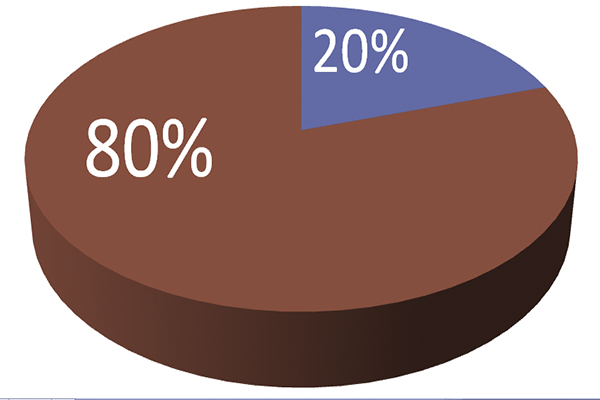

During January 2016 through October 2022, the monthly buprenorphine initiation rate increased, then flattened. This flattening occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting that factors other than the pandemic were involved. Throughout the study period, including in 2021-2022, only 1 in 5 patients who initiated buprenorphine were retained in therapy for at least 180 days, a rate similar to that found in a prior study examining data through the end of 2020.4,5

Chua K, Nguyen TD, Zhang J, Conti RM, Lagisetty P, Bohnert AS. Trends in Buprenorphine Initiation and Retention in the United States, 2016-2022. JAMA. 2023;329(16):1402–1404. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.1207

The stalled initiation rates are disappointing in the context of massive federal, state, and local efforts to increase buprenorphine treatment.

How do the authors explain these findings? [emphasis mine]

These findings suggest that recent clinical and policy efforts to increase buprenorphine use have been insufficient to meet the need for this medication. A comprehensive approach is needed to eliminate barriers to buprenorphine initiation and retention, such as stigma and uneven access to prescribers.

Chua K, Nguyen TD, Zhang J, Conti RM, Lagisetty P, Bohnert AS. Trends in Buprenorphine Initiation and Retention in the United States, 2016-2022. JAMA. 2023;329(16):1402–1404. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.1207

Other Explanations

I don’t doubt that stigma and barriers to access to prescribers play a role in these findings, but I imagine there are more important factors at play. After all, these were patients who received, accepted, and filled a prescription–they found a prescriber and stigma didn’t prevent them from starting treatment.

Is it possible the treatment isn’t delivering the outcomes these patients need or want? (It’s important to note that this could mean a lot of things. Some related to the medication, some not.)

For example, we know that polysubstance problems are the norm among people seeing treatment for opioid problems. If a patient presents with opioid use disorder, alcohol use disorder, stimulant use disorder, and cannabis use disorder, do they have 4 disorders? Or, do they have one disorder–addiction? If they have addiction, and we only treat opioid use, how successful is that likely to be? For someone with addiction, is “opioid recovery” an appropriate clinical endpoint?

For those patients with addiction, it is a uniquely complex bio-psycho-social-spiritual illness. Does the treatment these patients were provided address these complex and intersecting needs? Or, did it just target one of the biological factors?

Further along these lines, these findings may point to tensions in poorly developed and poorly aligned clinical, community, and individual models for recovery and wellness. Bill White explored this in a 2012 speech:

…historically the mental health field has had a very well-defined definition of partial recovery but literally no definition, until very recently, a full recovery from severe mental illness. We now have long-term studies of the course and trajectory of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, for example, that are really challenging that, and really beginning to signal the emergence of the concept of full recovery from some of the most severe complex psychiatric disorders.

On the addiction side, in contrast, we’ve had a very well-defined—a reified, if you will—concept of full recovery and no concept of partial recovery. In fact, it’s almost heresy to even begin to talk about a legitimized concept of partial recovery within the addictions field.

There’s a third concept within this framework that Ernie Kurtz and I ran into. We began to find scientific evidence in lots of anecdotal reports from therapists about people who got better than well. What I mean by better than well is that these are not people that we simply extracted the pathology out of their lives, but these are people who, not only went on to recover, but they went on to live incredibly rich lives, in terms of the quality of their life and service to their communities, and these are people who would later begin to talk about addiction and recovery was for them a blessing.

Experiencing Recovery, 2012 Norman E. Zinberg Memorial Lecture, William L. White

This “better than well” concept fits nicely with emerging models of post-traumatic growth.

In the context of the overdose crisis, more than ever, we need legitimized models and pathways for each to reduce harm, improve QoL, and achieve stable recovery for the greatest number of people. And, we need to avoid pitting them against each other.

Acknowledged or not, we have systems, resources, communities, and providers based on particular models. It might help to acknowledge this and address it much more explicitly. I imagine we’ll be stuck as long as we continue to have providers and systems that delegitimize and disavow responsibility for these pathways. This doesn’t mean providers need to be all things to all people, but validation and coordination would go a long way.

One of the major accomplishments of the earliest stages of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement was the founding of Faces & Voices of Recovery in 2001. Pat Taylor was its first Campaign Coordinator, heading the organization from 2003-2014. One of my early memories of her is watching her facilitate meetings of the Association of Recovery Community Organizations at Faces & Voices of Recovery (ARCO) where much of the early national recovery community gathered and worked to move forward, together.

For me, the most significant of these ARCO Executive Directors Leadership Academy meetings was on November 15, 2013, in Dallas, Texas. Bill White addressed the gathering with his thoughts on “The State of the Recovery Advocacy Movement.” It was an important time for me as I was learning about RCOs, and the work being done to strengthen recovery efforts across America. Pat was there, helping to hold the whole thing together in her own way.

One fact I want to highlight. Pat is not in recovery from an addiction. To the best I can determine, this did not matter in the least to any of us involved with Faces & Voices of Recovery. It certainly did not matter to me; it was something I soon forgot as I saw her in action embracing and supporting the needs of the fledgling national recovery community organization she led. She has lived most of her life working alongside us and her servant leadership style came through in everything she did. I have known a few other such recovery allies who take the time and energy to understand us and to listen and support our goals in ways that it matters little if their lived experience differs from ours. Her leadership personified that we embrace authentic allies who work with us in ways that resonate the “nothing about us without us” rallying cry that started at the very beginning of the new recovery advocacy movement and echoes through our current era.

Pat has over 50 years of experience developing and managing local and national public interest advocacy campaigns on a range of issues including healthcare, community development and philanthropy. While at Faces & Voices, she led the organization’s development into the national voice of the organized addiction recovery community, building a membership of over 40,000 individuals and organizations, creating ARCO and launching the Council on Accreditation of Peer Recovery Support Services. Today, Pat serves on the board of The Recovery Advocacy Project. She is a graduate of the University of Michigan and the author of numerous publications and recipient of numerous awards for her work.

- What brought about the formation of Faces & Voices of Recovery? How did you get connected to it? Is there a special memory you have about those early days?

Faces & Voices grew out of the efforts of many individuals and organizations focused on mobilizing and organizing the recovery community. Many were part of the National Forum, which met regularly in Washington, DC to advance addiction prevention, treatment, and recovery policies. Participants included Johnny Allem, Johnson Institute; Paul Samuels, Legal Action Center; Paul Wood, National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence; Sis Wenger, National Association for Children of Alcoholics; Bill Butinski, National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors; Claire Ricewasser, Al-Anon; William Cope Moyers, Hazelden Foundation; and many others. Jeff Blodgett organized the St. Paul Summit for the Alliance Project, bringing together local recovery advocacy groups, already strong and active at the local level, to develop a more organized constituency that would prioritize addiction recovery at the local, state and national levels.

Before coming to Faces & Voices, I ran the Alcohol Polices Project at the Center for Science in the Public Interest and worked at Ensuring Solutions to Alcohol Problems at George Washington University. It was people in recovery who showed up to testify for legislation to require warning labels on alcoholic beverage containers and to advocate for raising alcohol excise taxes. Through this work, I knew some of the people who organized the Summit and helped launch Faces & Voices. So, when I heard about the job opening for a Campaign Coordinator, I was familiar with some of the advocates. I was intrigued and excited by the opportunity after learning more about the campaign.

Faces & Voices took off after the Summit and did not become its own 501 (c)3 until 2004. As it was getting off the ground, Susan Rook, who was in recovery and had worked for CNN and Rick Sampson, who had been at SAMHSA, were its leaders. One of their early efforts included calling attention to the Christian Dior advertisement campaign for their product Dior Addict to highlight how the medium was being used to sensationalize, stigmatize and sell their perfume. Those early efforts led to some major stores pulling the product from the shelves, an early victory.

You asked me about my memories from the early days. One is learning about the importance of taking time and spending resources to understand the priorities of the recovery community. When I called to introduce myself to Faces & Voices board members, many brought up the Million Man March that had happened a few years earlier in Washington, DC. They wanted to organize a similar event to put a face and a voice on recovery, and stand up for recovery with family members, friends, and allies in the nation’s capitol.

As an organizer I was excited and kept this in mind as Faces & Voices developed programming. There hadn’t been many public recovery events since Operation Understanding in 1976. Faces & Voices worked with HBO on the release of its Addiction program, with A&E on its New York recovery rallies and helped organize Recovery Month marches and rallies that included voter registration, participation by elected officials, recovery entertainment and activities, fueling the building of a movement that operated in the public space.

When Bill White wrote that the central message of this new movement was that permanent recovery from alcohol and other drug-related problems is not only possible but a reality in the lives of hundreds of thousands of individuals and families, it was a dramatic turning point and spot on. He articulated what many people had been thinking individually — that the views and needs of people in recovery, family members, friends and allies could not be ignored if we wanted to make it possible for more people to recover from addiction to alcohol and other drugs. To shift from “treatment works,” and “addiction is a disease,” this new collective movement would need to work to make policies and practices recovery-focused and recovery-oriented. At the time, we didn’t even know how many people were in recovery in the U.S.!

Bill White has played a number of important roles in the New Recovery Advocacy Movement. One that probably no one anticipated is that his efforts to document recovery history through his work including Slaying the Dragon was and remains vital to the development of the movement. In all of his writings, presentations and consultations, he has helped us understand that people in recovery, family members, friends and allies have unique knowledge and skill sets that must be front and center if we are going to make it possible for even more people to find and sustain recovery.

His work contributed to the development of Faces & Voices’ mission to mobilize the addiction recovery community to seek and implement public policies that support recovery from addiction to alcohol and other drugs; break down barriers that preclude access to recovery; change public attitudes to prioritize addiction recovery and show the public and policymakers that recovery is a reality for over 23 million Americans and their families in communities across the country.

One thing we got right was working hard to make sure that the voice of the recovery community was front and center in all of our work. Early on, we wanted to develop recovery messaging, so that the public could understand the reality of recovery and so that advocates had language to talk about their recovery. We tested different messages using focus groups of people in recovery. They rejected words like “survivor” or “champion” used by other movements and embraced person-centered language. We started using the term “person in long-term recovery” after listening to people with lived experience.

Another is that at the Summit and throughout its history, Faces & Voices worked hard to embrace all pathways to recovery, including people using various pathways in its leadership as well as family members. We also learned to appreciate the power of the bipartisan nature of our work and the power of story. In St. Paul, Senator Paul Wellstone (D) and Representative Jim Ramstad (R) spoke out, transcending the partisan divide. Just as Republicans and Democrats alike are affected by addiction, recovery leaders emerged from both sides of the aisle. That started at the Summit and continued with the formation of the bipartisan Addiction and Recovery Caucus, passage of the Wellstone Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, among other efforts.

One thing that was missed, and there were others, was understanding and promoting harm reduction policies and practices.

- What was the relationship between Faces & Voices at the national level and recovery community groups across the country? Our history illuminates that inherent tensions can occur. This was true in the era of Marty Mann and the NCA and other eras in recovery movement history as well. Reflecting back, what helped pull groups together in the time you were involved with Faces & Voices?

We had a very close relationship, highlighting the work of those organizations and including recovery communities in all levels of decision making, formally and informally. We worked to develop programming and activities that would strengthen their ability to carry out their missions on the ground back home in their communities.

We also worked hard to have a board that represented the diversity of the recovery community – including recovery pathways, regions, race, gender, and recovery status. One important effort was to have At-large and regional representatives on our Board to ensure connection to local communities. Local groups could interact with regional Board representatives, who could bring local concerns to the national organization.

In those early years we worked to grow Recovery Month participation by local groups, as members of the Recovery Month Planning Partners at SAMHSA and through Faces & Voices networks. We developed programming like Rally for Recovery! National Hub Events that occurred in different communities across the country year to year. People organized runs, marches, marathons, rallies, concerts, and speaker events. And we made sure to use these opportunities where the recovery community gathered, to register voters and engage elected officials.

Over the years, we developed opportunities for individuals and organizations to be part of the movement. We developed Recovery Community Organization Toolkits that local grassroots communities could use to develop their own RCOs to strengthen recovery capital in their own communities. Groups could then get involved in the Association of Recovery Community Organizations (ARCO). We organized leadership academies that brought leaders from RCOs together from across the nation so they could share their experiences, learn together and help inform us on how to support their needs. We worked hard to use our national presence to strengthen the RCOs across the nation. Working with RCOs we developed CAPRSS to set accreditation standards for RCOs.

There was a tremendous void in recovery research. Working with Alexandre Laudet, we put out the very first national survey The Life In Recovery Survey to quantify and measure the effects of recovery over time. People across the country took the survey and it’s been widely shared, illuminating the power of recovery to transform lives and communities.

The talented and dedicated people who served as Board members and those who worked at Faces &Voices were critical to its growth and development. They were amazing and many went on to serve in key positions, influencing public policy and perceptions of recovery. People including Carol McDaid, Dona Dmitrovic, Tom Hill and Tom Coderre, helped build Faces & Voices from the ground up.

It was important. When Bill White made that presentation, we were in a period of transition in the recovery movement. Faces & Voices was over ten years old! Peer support was beginning to look more professional, and issues around the risks and benefits of professionalization of lived experience workers were surfacing as well as the role of advocacy in the movement. He raised the importance of keeping eyes on community building recovery capital and anti-discrimination efforts that were necessary to more fully realize opportunities for long-term recovery.

Here’s one example of the changes in the movement. The Association of Persons Affected by Addiction hosted the Leadership Academy at their recently opened Recovery Community Center. They were just getting off of the ground twelve years before. They had reached the level of operation that they were undergoing CAPRSS certification in 2013.

Recovery-oriented services were expanding rapidly across the country and recovery was coming out of the closet for many Americans. New organizations like Shatterproof were being formed and the Anonymous People, which at its core is the story of Faces & Voices of Recovery, had been recently released and was being aired across the country. There were so many new voices, interests, and ideas to think about. The movement was growing with all of the opportunities and challenges that came with it.

When I reflect back on that moment now, what we were working on was recovery representation across our whole system of care and support. We knew it had to be about more than peer services incorporated into the treatment system.

What do you see as the greatest accomplishment during the era you were at the helm of Faces & Voices of Recovery?

There was not just one thing. We were working on a number of fronts to advance recovery. We put together ARCO and the Leadership Academy to focus on and support recovery community organizations. We developed CAPRSS to support standards for peer recovery support services and keep the recovery community in the driver’s seat. We developed and released the Recovery Bill of Rights, a statement of the principle that all Americans have a right to recover. In many ways, that statement reflects what Faces & Voices accomplished, the recovery community coming together as an organized community and constituency, building its own agenda, and acting collectively to implement it with support from allied organizations.

- What insights do you have now looking back at the recovery movement and what it has accomplished?

I look back and realize that a lot has been accomplished. If you think back to what was happening at the first Recovery Summit in 2001 and what’s going on today, it’s truly inspiring. Hundreds of recovery community organizations and recovery-oriented policies developed out of our efforts. Hundreds of thousands of people have participated in public events celebrating recovery, with many of them registering to vote and participate in local, state and national elections. There were successful efforts to expand legal protections for care through the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) made possible because of the advocacy of the organized recovery community. We showed America that there is hope, that recovery is a reality and that recovery voices matter.

Even as I say this today, addiction is exacting a devastating toll on families and our communities. So much more needs to be done. To continue moving forward, we are going to have to work even harder to be inclusive of all the diverse recovery and other allied groups that have formed. There is going to need to be a concerted effort to figure out how to bring all of these groups together and work on issues of common concern.

What are you doing now?

One of my passions is gardening, so I’ve had a chance to build my small landscaping business. My daughter and her family moved from Austin, TX into our house in Maryland, so my husband Bill and I are now renters. We’ve been traveling a lot and during the pandemic, we were zoom school proctors for our grandson, quite the experience. I also still have my hand in recovery efforts and serve on the Board of Directors for the Recovery Advocacy Project, I’m really excited about the work they are doing.

- What would you tell future recovery community leaders to pay attention to in respect to risks and opportunities?

I’d suggest one way to move forward is to organize to address the way that discriminatory policies create barriers for so many people to get their lives back on track. We should actively work to eliminate discriminatory policies where they exist in healthcare, employment, housing, and quality of life issues. If these policies are ignored – or in some cases, strengthened, it will be a missed opportunity for building recovery-oriented communities.

I’d encourage them to pay close attention to what can happen if there is an overemphasis on peer services in their organization and community. It’s very important to keep a focus on advocacy and building strong communities of recovery.

There’s an untapped opportunity that has been well used by other social movements – running candidates for public office. A few people have already run and won as persons open about their recovery in the U.S. As a matter of fact, they used their recovery status to recruit supporters and build support for their campaigns.

And last, we need to build a dynamic movement that is creative and inspires others to join in.

- Is there a question I did not ask you would like to answer?

I think it’s important to highlight how and why it’s important for people to join us and get involved. While some people who were in the formative stage of the movement ended up with government appointments, there are so many opportunities to organize and act locally and engage a new generation of recovery advocates.

.

After screening for harmful alcohol use, researchers in a 2022 study1 examined differences based on age – with some interesting results.

The study examined…

…data from 17,399 respondents who reported any alcohol consumption in the last year and were aged 18 and over from the 2016 National Drug Strategy Household Survey…”

The authors said the aim of their study…

…was to measure age-based differences in quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and how this relates to the prediction of harmful or dependent drinking.”

The bottom-line finding was that:

- quantity mattered more for the older population, and

- frequency mattered more for the younger population.

The authors stated…

In older drinkers, quantity per occasion was a stronger predictor of dependence than frequency per occasion. In younger drinkers the reverse was true, with frequency a stronger predictor than quantity.”

Interestingly, based on their results, the authors wonder if…

- heavy episodic drinking among younger people is the kind of drinking from which most can “age out”, without intervention;

- the factor of consistent drinking among young people can eventually be developed and refined as a screening marker to help prevent serious clinical progression;

- and if screening problematic drinking among older adults should center on drinks per occasion.

The authors close by stating…

…it appears that clinicians…might wish to look out for young drinkers who are drinking like older people (frequently) and older drinkers who are drinking like young people (more per occasion).”

They note that common tools currently used to screen for alcohol problems do not function in this manner.

A simplified yet thorough overview and discussion of this research is available.

Reference

1Callinan, S., Livingston, M., Dietze, P., Gmel, G., & Room, R. (2022). Age-based differences in quantity and frequency of consumption when screening for harmful alcohol use. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 117(9), 2431–2437. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15904

Very recent original research has found initial evidence that the paternal use of alcohol prior to conception produces physical defects and abnormalities that resemble those caused by maternal drinking during pregnancy.1

What kinds of abnormalities were found to be associated with paternal drinking prior to conception? The study found alcohol-related fetal abnormalities of the brain and face.

But the researchers also found another impact. They found paternal alcohol use before conception also increases the impact of maternal drinking on development of the fetus.

Interestingly, rather than merely examining drinking as an all-or-nothing variable, the investigators found that the effects of pre-conception paternal drinking were correlated with alcohol dose.

A simplified overview and discussion2 of this research is available.

The authors discuss the relative lack of research in this area, stating that,

…due to the misconception that sperm do not transmit information beyond the genetic code, the influence of paternal drinking on the development of alcohol-related birth defects has not been rigorously examined.

One might wonder if this area of research holds relevance for public health promotion The researchers state that,

In 1981, the U.S. Surgeon General issued a public health advisory warning that alcohol use by women during pregnancy could cause birth defects.

and,

…our studies are the first to demonstrate that male drinking is a plausible yet completely unexamined factor in the development of alcohol related craniofacial abnormalities and growth deficiencies.

They go on to state that…

Our study demonstrates the critical need to target both parents in prepregnancy alcohol messaging and to expand epidemiological studies to measure the contributions of paternal alcohol use on children’s health.

References

1Thomas, K. N., Srikanth, N., Bhadsavle, S. S., Thomas, K. R., Zimmel, K. N., Basel, A., Roach, A. N., Mehta, N. A., Bedi, Y. S., & Golding, M. C. (2023). Preconception paternal ethanol exposures induce alcohol-related craniofacial growth deficiencies in fetal offspring. The Journal of clinical investigation, e167624. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI167624

2Knight, R. Father’s Alcohol Consumption Before Conception Linked To Brain and Facial Defects In Offspring. Texas A&M Today. April 12, 2023.

“Safe supply” is a promotional term, when what is needed is careful evaluation of the risk of such initiatives to increase addiction, toxicity, and overdose.

Roberts, E., Humpreys, K. (2023) “Safe Supply” initiatives: Are they a recipe for harm through reduced healthcare input and supply induced toxicity and overdose? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.23-00054

I’ve recently published a couple of posts on drug policy (here and here), trying to shine a light on how broad and complex the topic can be.

This is good news and bad news.

The bad news is that “simple” solutions are never as simple as they sound and that the devil will be in the details. Simple concepts get very complicated very

The good news is that we have a lot more levers than we typically associate with drug policy and that some of them ought to be fairly easy to implement — for example, things like marketing restrictions and zoning of outlets. These policy decisions typically won’t solve “the drug problem”, but they have the potential to influence it.

One of the questions raised was, if we legalize and regulate drugs and one of the goals of that decision is to improve the safety of the drug supply, how do we manage and prevent innovation in the drug supply?

The NY Times has a story on the xylazine’s veterinary use and the search for policy responses to its emergence in the drug supply.

Stories about the emergence of fentanyl and xylazine often frame them as examples of poisoning of the drug supply. However, their emergence could just as easily and maybe more accurately be framed as innovations that serve a purpose — to ensure higher potency, lower price, and extend the duration of the effects of the drug.

We demonstrated that preference for fentanyl was increasing between 2017 and 2018 among our cohorts of PWUD who used opioids. In a multivariable analysis, younger age and daily crystal methamphetamine injection remained independently associated with preference for fentanyl. Most commonly reported reasons for preferring fentanyl included more euphoria, longer effects, and development of high opioid tolerance.

Ickowicz, S., Kerr, T., Grant, C., Milloy, M. J., Wood, E., & Hayashi, K. (2022). Increasing preference for fentanyl among a cohort of people who use opioids in Vancouver, Canada, 2017-2018. Substance abuse, 43(1), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2021.1946892

Calls for “safe supply” often frame it as a simple process of ending prohibition (legalizing), getting law enforcement out of the picture, and regulating supply. However, what does that regulation look like? Does it allow innovations like fentanyl and xylazine? How are those regulations enforced and by who?

These calls also often elide the reality of the enormous public and private burdens associated with our regulated supplies of alcohol and tobacco.

All of this brings me back to the belief that we are very poorly served (harmed, actually) by sloganeering in drug policy discussions, whether those slogans are designed to promote a “war on drugs” or a “safe supply.” (It’s worth noting that harm reduction advocates used to avoid “safe” and preferred “safer” as an acknowledgment that PWUD who engage in harm reduction practices continue to face significant risks associated with their drug use.)

Mark Kleiman challenged us to confront drug problems and drug policy by facing the limitations of policy “solutions”, acknowledging the difficult decisions, and not being paralyzed by those limits and difficult choices.

Any set of policies will therefore leave us with some level of substance abuse—with attendant costs to the abusers themselves, their families, their neighbors, their co-workers and the public—and some level of damage from illicit markets and law enforcement efforts. Thus the “drug problem” cannot be abolished either by “winning the war on drugs” or by “ending prohibition.” In practice the choice among policies is a choice of which set of problems we want to have.

But the absence of a silver bullet to slay the drug werewolf does not mean we are helpless. Though perfection is beyond reach, improvement is not. Policies that pursued sensible ends with cost-effective means could vastly shrink the extent of drug abuse, the damage of that abuse, and the fiscal and human costs of enforcement efforts. More prudent policies would leave us with much less drug abuse, much less crime, and many fewer people in prison than we have today.

Dopey, Boozy, Smoky—and Stupid by Mark Kleiman

[Ed. Note: big thanks to SMART Volunteer Anne Devenport for writing this guest blog]

The DISARM tool is used in SMART Recovery to deal with urges – participants in recovery meetings imagine that an unpleasant salesperson is trying to push them into their addictive behavior, so they use the DISARM tool (Destructive Imagery and Self-Talk Awareness Method) to help them deal with the imaginary salesperson, and so deal with their urges.

A participant once asked during a Family and Friends meeting if it would be possible to make the DISARM tool relevant for Family and Friends. We might first start by identifying what the salesperson might be tempting us, as Family and Friends, to do.

We might feel strong urges to:

Nag our Loved One

Protect our Loved One

Clean up our Loved One’s messes

Call our Loved One’s boss to explain why they are late

Hide our Loved One’s behavior from others

Give our Loved One money for their addictive behavior

Fix our Loved One’s problems

….. and many other things

The DISARM tool suggests that we might call our salesperson a name (The Creep, The Sleazeball), and that we might tell the salesperson to get lost. In this way we are personifying our urge to fix/protect/nag, which might help us to recognize that the urge isn’t part of us, and that we have the power to refuse it – to refuse the salesperson.

There are a few questions we might ask ourselves when the salesperson turns up in our lives. Let’s examine the DISARM tool from the point of view of someone who wants to jump in and fix their Loved One’s problems – they want to buy them a new cell phone when their Loved One has broken theirs; they want to repair their Loved One’s fender bender; or they want to vigorously edit their college-aged son’s homework to prevent them from getting a bad grade. The questions of DISARM for Family and Friends might look like this:

- Do I have to fix my Loved One’s problems just because I strongly want to?

Our answer might be:

“No, it would be easy to give in, but I don’t have to. I have resisted

fixing in the past, despite the demands of the salesperson, so I

know that I can do it.”

- Will it be awful to stop myself from fixing my Loved One’s problems?

Here we might tell ourselves:

“No, it won’t be awful. It might be unpleasant to watch my Loved

One trying to fix their own problems, but it won’t be awful. If I

don’t give in to the salesperson this time, it will be easier to resist

in the future. I know that in the long-term my stepping back from

fixing everything might be helpful for my Loved One – it will send

them the message that I have confidence that they are capable of

fixing their own problems.”

- Am I somehow entitled to have an easy life when dealing with my Loved One?

We might answer this with:

“No, I am not entitled to an easy life with my Loved One. The

salesperson is going to keep on trying to tempt me, that’s just a

fact of life, and I can deal with it. Like everyone else, I encounter

difficulties in life, and I know that I can work through these.”

Additionally, whenever the salesperson rears their unwelcome head, and tempts us to jump in to fix our Loved One’s problems we can turn to section 10 of the Family and Friends Handbook, where we find the following questions:

Will changing my behaviors truly hurt my Loved One? Yes, they may get angry, but what is that in comparison to the long-term harm of addiction that I am working to avoid?

What will hurt me more: changing my behaviors, or knowing that I didn’t do anything to change my behaviors?

What can I expect to happen if I don’t change? Will things get better?

So, at the risk of sounding like a salesperson…consider buying into DISARM – another great SMART tool that we can add to the Family and Friends toolbox.

Resource links

DISARM the Addiction Salesman (article)

Working in the substance use service system has always been a challenge. This was true even from its early days. We help people in some of their most difficult moments with few resources to support what they need to get well. We operate under constant triage conditions. Yet despite this, we tend to oversell those shining moments of reward experienced helping a person on their recovery journey to get people interested in taking on the calling of serving people in our SUD care system workforce. Maybe we should instead tell recruitment prospects the truth.

Many of us love this work. We can play a part in people saving their own lives and redefining how they want to live. We witness the immense changes that can occur in ways that change the trajectory of whole families and at times large swaths of the community. Lives are changed in part because of the work we do. This is also essentially our workforce recruitment narrative.

It will be obvious to most that I lifted part of the title of this post from the US Marine Corps. It may seem overly dramatic, but there are parallels at least in one way. The Marines go to where they are needed, when they are needed, whether or not they have the resources to do the job. This is not an uncommon experience in the SUD service environment, particularly in the public sector. We serve because we are needed, often without the things we need to do the job because lives hang in the balance. Triage and improvision are the tools we far too often have to do our jobs. That is the truth for so many of us.

Despite this, we lead with the warm fuzzy good stuff despite the cold hard reality of the work. Perhaps it is not the right way to recruit people for our field. I have come to this conclusion following a lot of conversations with people in diverse settings across our system in recent weeks with a lot of common notes and themes. We need to tell the truth about the work to those who are considering a career in our field. Failure to do so is a set up as fresh-faced workers once they experience what it is really like in the trenches. Vital work that tests your skills and stamina.

Far too often in this era, our workforce is dealing with death in a close up and intimate way, perhaps in no greater frequency than within our peer workforce. In the age of Fentanyl and Xylazine, care is more complicated, recovery efforts more challenging and the risk of lethality dramatically increased. I was unable to find much in respect to SUD treatment protocols or recovery engagement strategies beyond withdrawal management for this new trend. Front line workers with direct experience have shared with me that persons using these drugs together are more challenging to engage in a change process. This is also historically the case as academic data lags practice as new drug use patterns unfold. But in this I am hopeful.

I know that history shows us that it is these same front-line workers who will find practice strategies that will help improve outcomes over time. Every prior emergent drug use patten has shown us that it is our frontline workforce who figure things out in ways not unsimilar to how Mobile Army Surgical Hospital workers learn to improvise in the moment and adapt to save lives. Grim, challenging, and imperative work that does not translate well to a feel-good recruitment campaign. Such work is not for everyone.

The work takes a toll on you. You see and experience traumatic things that will stay with you for the rest of your life. Resumption of use can be a risk, as can be experiencing high levels of stress, secondary trauma and even potentially the risk of physical harm. All far too often for less money and longer hours than slinging burgers.

It is a space ripe with snake oil sellers, hustlers and hucksters. Also not a new trend, they have been around well before the era of the “Keeley Cure” which included gold injections to cure alcoholism that became popular a millennia ago. All the resources to address our current crisis have brought out a host of these kinds of people promising solutions marketed in the most appealing ways. They often find their way to the front of the line because they offer compelling and simple solutions to situations that in truth defy such simplicity. It can take awhile to play out as they burn through resources. All of which can be quite disillusioning for people seeking to do this work for better reasons than to make a lot of money or to become a guru. We need recovery custodians dedicated to hard work, not rockstars who burn bright and far too often leave us with more devastation and fewer resources when the inevitably implode.

Other long-term challenges in our field are being exacerbated by our current circumstances. High quality, consistent supervision has always been a challenge perhaps in no small part to the triage dynamic of the work. Supervision while under fire often seems secondary even as it is critical. Supervision is getting even harder to find due to the increasing loss of experienced workers. Experienced workers are retiring, giving up on the work due to the mountains of paperwork and incessant bureaucracy or simply taking jobs that pay more, which includes most other types of work without regard to training, educational level, or experience. Often for more pay, fewer work hours and lower stress. I cannot recall a conversation with seasoned colleagues in the last year that did not include the myriad of reasons to just do something else, yet many of them carry on. Yet attrition is occurring, which leaves fewer mentors for less experienced workers who far too often are learning through trial and error.

It is important to understand that most everything in this piece was true 20 years ago but we kicked the ball forward. Over the decades policymakers struggle to prioritize needs without the capacity to meet the ones on the table. They have been constantly challenged with triaging the crisis of the moment with limited resources to address anything not on fire. Workforce development has consistently seemed to be the thing we will address tomorrow when the current crisis ends. There is always a new crisis.

Because of all of these dynamics, it is also true that recovery far too often occurs despite our care system and not because of it. Our systems have long been designed to deliver band aids instead of habilitation and long term support. We provide comfort care or short-term treatment in ways that deliver people back to our front doors or an early grave and not long-term recovery, which remains not much more than an afterthought. Our workers far too often find themselves working in systems of care that don’t work. Helping people heal in these kinds of environments takes a lot of courage, stamina and can at times feel like an act of defiance.

Pointing out these truths in our systems can be dangerous. Far too often truths are uncomfortable, and a lot of energy can be consumed across our systems of care avoiding them. Newcomers to our system often learn this the hard way. They point some things out that become evident to them doing the work on the ground and get swatted down by the system. This is perhaps no truer than for recovering people with the asset of lived experience being eclipsed and discounted due to the deep sense of unworthiness and distrust our society has for people who have experienced addiction so pervasive in our healthcare systems and beyond. There is also an inverse relationship between resources and proximity to the problem. The closer to the street you are the less resources and credibility you have, while the money and answer people are far removed from the reality of real-world conditions. This too is because of stigma.

So when all else fails, perhaps we should tell the truth. It is not a job; it is a calling, and not an easy one. We do this work because it is vital, not because it is easy or that everyone we work with has a fairy tale outcome. We are simply not working in that kind of environment, and even properly resourced the gravity of the work is life and death, not the thing of fairy tale endings, at least our modern versions of them. Despite it being hard and far too often done in the face of stiff headwinds and a sea anchor fastened to our stern, we push forward. We do so because we must.

The final irony is that when our efforts fall short because we are under resourced and meager resources are rationed out like thin gruel, it gets played as the clients are failing or our workforce is failing and not that we were never resourced to succeed but instead to triage. This is true for any highly stigmatized condition, but perhaps none more so than ours.

If we tell the truth about how difficult it really is, perhaps it will draw people in who are more intentional about why they want to serve our communities in need. And perhaps with such truth telling we may actually end up helping us address these systemic challenges in ways that things actually do change.

To those of you out there who get up and do the work knowing the above truths and do it anyway. I salute you.

And for those who think you can navigate all the above, the hardest job you will ever love, we welcome you. We need you!

|

The 2023 Richard Saitz Memorial Lecture registration is now open! We are pleased to welcome Dr. William Miller to present, “Going Upstream: Addiction Care for the Masses.” Description: Although the vast majority of people with diagnosable substance use disorders will never receive specialist addiction treatment, most will recover. Dr. Saitz was passionate about serving this at-risk population. Drawing on his 50 years of research, Dr. Miller will discuss various ways of “going upstream” to intercede at earlier stages of problem development including (1) teaching moderation skills, (2) brief opportunistic interventions such as SBIRT, (3) motivational interviewing and a person-centered clinical style, and (4) providing behavioral health services within mainstream healthcare. Join us on May 3 at 8 pm ET Register HERE Dr. William R. Miller is Emeritus Distinguished Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at the University of New Mexico having served as Director of Clinical Training and as a Founder and Co-Director of the Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions (CASAA). His publications include 65 books and over 400 articles and chapters. Fundamentally interested in the psychology of change, he introduced the method of motivational interviewing in 1983. The Institute for Scientific Information has listed him among the world’s most cited scientists. |

|

Richard Saitz, MD, MPH was a leader in the addiction treatment world and a friend of SMART Recovery. He was a keynote speaker at our 25th Anniversary Conference in 2019. You can read more about Dr. Saitz’s life and accomplishments here |