“…legitimacy is based on three things. First of all, the people who are asked to obey authority have to feel like they have a voice–that if they speak up, they will be heard. Second, the law has to be predictable. There has to be a reasonable expectation that the rules tomorrow are going to be roughly the same as the rules today. And third, the authority has to be fair. It can’t treat one group differently from another.” – Malcolm Gladwell

I found this quote above last April and half wrote this piece. One year later, it still nails what happens when systems under stress move away from their focus and only pursue narrow agendas. They get insular, reactive and autocratic. Ever shifting rules and favoritism erodes everything. They maintain the illusion of inclusion by only involving people when all the important work is done by a few favored groups. Institutions who value authentic inclusion don’t do this. Refocusing institutions who have strayed from legitimacy requires commitment to transparency and openness.

Authentic inclusion occurs without a predetermined outcome in mind. They lead to solutions founded in consensus building that could not occur in any other way. They also are more effective. Anything less reduces the legitimacy of both the process and the outcome. This leads to a system in a perpetual crisis state unable to achieve big things.

Our SUD service system is fraught with inequity. As an analogy, Walmart and local neighborhood groups do not have equal power when in disputes. Walmart ends up being treated more favorably than everyone else. They have nearly unlimited resources. They can outmaneuver all the singular voices. Individuals only have power in these dynamics when they coalesce around solutions. This also plays out in the SUD care systems across our states in resources allocation and policy development. The golden rule of “he who has the gold makes the rules” is in play. The recovery community is left out or coopted. The recovery community has no gold; our currency is community, valued when it comes together. It is the fundamental truth of our own history that outside groups profit from our division at the expense of our collective well-being. Inequity is the standard of our system and is only overcome when we stand together. We must.

These same dynamics play out on the international scale as well. This Brookings Institute article notes that economic prosperity (in terms of GDP) can become decoupled from social prosperity (in terms of well-being in thriving societies). People are getting wealthy as societies fail. Economic prosperity without social prosperity erodes nations. The recoupling dashboard, is an attempt to measure well-being beyond the GDP. Change the measure, change the outcome. Think recovery capital here. We can’t fix the SUD system without strengthening our recovery communities. This is a function of the five-year recovery paradigm, a long term wellness orientation. Not a short-term pathology focus.

Getting there is complicated for our whole system. One big barrier is our language. So much of our language around addiction and recovery is inoperable. The SUD harm reduction, treatment and recovery communities find ourselves in a situation similar to what playwright George Bernard Shaw once noted as Britain and the US as “nations separated by a common language.” We talk past each other using the same words even as those terms mean different things to each of us! We have not invested the time to develop consensus on what our common terms mean. This lack of common language also creates a barrier to thinking and acting systematically to address the common challenges we face. As a consequence, we talk past each other with little hope of deeper understanding. Our own tower of babel.

In seeking solutions, I looked towards our history. Last year, I interviewed key figures in the New Recovery Advocacy Movement (NRAM). Those interviews are HERE. It was an amazing experience, I gained a lot of insight about the movement, and I am grateful for opportunities I have to share what I have learned. The biggest takeaway for me was that several interviewers emphasized the need for broad, ongoing dialogue to develop common objectives. Not strictly facilitated groups focused on obtaining discrete goals managed by the conveners, but an authentically open process.

I am both equally encouraged and discouraged in respect to dialogue across our communities. It runs the gamut from productive conversations on difficult issues to the tired old dynamic of people waiting to pounce when their confirmation bias lights up and they move to cancel out the offender, shutting down all discourse. Creating wounds instead of healing them. Dollars are dangled to divide, more often than used in ways to bring people together. We need a system that treats all groups equally to find consensus. Strong bridges can only be built on this bedrock of legitimacy.

I see parallels to our current times and where we were 20 years ago. Things are undeniably broken. Addiction and recovery are complex issues. The power of the moment we are in is the opportunity for consensus building. It must be fixed if we are to develop and effective and cohesive care system. Such solutions take time and commitment. But as NRAM shows us, such efforts are well worth it.

What we do, or do not do will be how history remembers us.

When it comes to trying to improve access to residential rehabilitation in Scotland, one thing I’ve heard too often from doubters is: ‘there’s no evidence that rehab works’. Ten years ago I was hearing the same thing about mutual aid, which was recently (at least in terms of Alcoholics Anonymous) found to be as effective, if not more effective, than commonly delivered psychological interventions.

There are a some problems with the ‘there’s no evidence that it works’ line. The first is that even if we accept the faulty premise that there is a poor evidence base, this is often taken as evidence that rehab doesn’t work, which is illogical. The second problem is that while there is evidence, some people don’t know about it or, for a variety of reasons, choose to dismiss it. What we can say is that the evidence base is weighted towards some areas (e.g., medical interventions) at the expense of others. The third issue for me is that while we need to find ways to balance the evidence base, we will not find more evidence if we’re not looking for it.

In order to add to the evidence base, we published a paper in 2017[1], evidencing one-year outcomes following therapeutic community (TC) residential rehab in Scotland. In a review of recent literature it was good to see that our study was rated to be methodologically strong, Those patients going through TC rehab saw improvements across a range of domains. This was in keeping with previously published research.

Therapeutic community (TC) treatment is a particular type of rehab. In a TC, the community of patients itself is the main agent of change. In a highly structured programme, residents live together, share meals, participate in groups, undertake tasks within the service and share leisure activities. Lived experience in the staff team and in peer volunteers is an important component and a variety of interventions and scheduled activities offer opportunities to identify and change unhelpful thinking and behaviours, but more importantly, help to reduce psychological problems, improve social functioning and help individuals reach their goals.

Australia is producing research on residential treatment. Petra Staiger and her colleagues down under followed up 166 individuals going through TC treatment at two sites[2] and took stock of where they were nine months after discharge. They scoped out wellbeing, substance use, dependence, mental health, physical health and social functioning.

The commonest problematic substances were alcohol, cannabis, heroin and amphetamines. At baseline, participants had high levels of dependence, compared to treatment-seeking population norms. (Incidentally, we found the same in our study, in keeping with the observation that those referred to TCs have high problem severity). At baseline, individuals had very low levels of wellbeing and substantial socio-economic disadvantages.

It is critical when examining TC outcome research to understand that people accessing TC treatment tend to have more complex psychosocial concerns than people attending outpatient treatments and other shorter-term residential treatment

Petra Staiger & Colleagues,

The researchers followed up 90% of the original sample – an extremely high follow up rate for a study of this kind. At nine months post-treatment they found that 68% of individuals reported complete drug abstinence in the prior ninety days and 32% reported complete alcohol abstinence. Alcohol quantity and frequency of drinking was reduced by more than 50% and both alcohol and drug dependence scores were reduced by over 60%. Wellbeing scores doubled and psychiatric severity scores halved. Longer stays in the TC had better outcomes.

This study chimes with what we found in our outcome study from TC treatment in Scotland – high baseline problem severity but significant improvements in a range of measures one year after treatment. There are good reasons to be positive about the impact of rehab and plenty of evidence with which to challenge the naysayers.

Having said that, and while very welcome, such findings need to be seen in the context of a wider treatment system where a full menu of options is available. Not only that, but the components of the treatment system need to be linked in a way that makes navigation between them simple and as safe as possible. When rehab is seen as separate from mainstream treatment – a remote silo – then the chances of individuals getting there easily is reduced and the risks are likely to be higher. We need an integrated system of care and I hope we are moving towards that here. As we can see, according to the evidence, there are good reasons to make rehab an integral part of treatment systems.

Based on their methodology, high follow-up rates and outcomes, the authors conclude:

The findings reported can be viewed with confidence and are likely to generalise to the TCs within Australia and beyond.

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

Main photo credit: Nazarkru@istockphoto under license

[1] Rome AM, McCartney D, Best D & Rush R (2017) Changes in Substance Use and Risk Behaviors One Year After Treatment: Outcomes Associated with a Quasi-Residential Rehabilitation Service for Alcohol and Drug Users in Edinburgh, Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 12:2-3, 86-98,

[2] Staiger PK, Liknaitzky P, Lake AJ, Gruenert S. Longitudinal Substance Use and Biopsychosocial Outcomes Following Therapeutic Community Treatment for Substance Dependence. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(1):118.

Peer-to-peer fundraising has proven to be a fun, engaging, and effective way for nonprofits to raise funds for the vital work they do in service of their communities. Now SMART Recovery is proud to roll out its very own TAKE ON ADDICTION campaign starting April 1st!

This is a first-of-its-kind global initiative to Smash the Stigma associated with addiction and inspire people everywhere to confidently step forward, access SMART Recovery’s free tools and mutual support meetings, and truly get the help they need.

As a vital member of the SMART Recovery community, YOU understand more than anyone how important these efforts are. We invite you to take part. Simply sign up here to set up your personalized online profile, then set daily or weekly goals to walk, run, cycle, or choose your own activity to raise funds for the campaign.

Create a team! Invite your friends and colleagues to join it or invite them to start their own teams!

Your fundraising efforts this April will not only help you get really fit, but also push SMART Recovery ever closer to its ultimate goal of having everyone, everywhere, live Life Beyond Addiction.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

In the first part of this article, I’ll note one particular barrier I have heard expressed about the idea of changing an addiction treatment campus to “tobacco-free” or to the idea of a tobacco-free model of care. And then I’ll discuss a few responses to that barrier.

In the second part of the article, I’ll provide a list of some possible reasons why 480,000 deaths1 a year due to smoking don’t get our attention and don’t cause us to adopt a smoke-free model of addiction treatment.

PART 1: One particular barrier, and some responses to that barrier.

One Particular Barrier

The organization where I work made the switch2 to a tobacco-free campus back in 2013. From time to time after we made that change, I’ve been asked an interesting question. The question comes in a few different versions, and it points to one particular barrier against making the change to a tobacco-free addiction treatment method and campus.

Here are the two most common versions of the question:

- “Isn’t it the person’s right to smoke cigarettes?”

- “But isn’t smoking cigarettes a human right?”

Interestingly, every time I have been asked any version of this question it has been asked of me by people with clinical careers in community agencies providing addiction treatment and mental health counseling services or related human service help.

On the topic of tobacco, it seems as if the professional part of our field knows the right answer but keeps walking in the wrong direction.

I wanted to share a few of my responses to that question, in no particular order.

Response #1: Treating One Addiction While Ignoring Another

In this reply I ask what it even means to claim to provide “addiction treatment” and yet treat one addiction while ignoring another.

One question of my own that I’ve used as a probe of our intent as addiction professionals is:

“If a person we treated for alcoholism dies of emphysema due to continuing smoking cigarettes, did we really treat their disease, or just an alcohol use disorder?”

We all know the standard response to that challenge is, “We don’t ignore cigarette smoking”. And in this context the other response that “…addiction isn’t really a disease…” is outside the meaning of the question.

Rather than contend with the point of my probe, some will state their…

- use of motivational interviewing, NRT’s, patient education, and a tobacco-specific group; or

- inclusion of tobacco as a part of the patient’s clinical assignments or homework.

But I’d like to state that if it was cocaine or methamphetamine the patient was smoking instead of cigarettes, we would likely not be so lackadaisical or cavalier.

Response #2: Do No Harm

Another response I give at times is one concerning “Do no harm.”

Addiction professionals with clinical credentials have a clinical duty to those we serve. Among those duties we are to:

- Not do harm to those we serve

- Provide an atmosphere or environment of care that does not harm any patient

Even if it was the human right of one person to smoke cigarettes, would that one person’s right within their personal space and life remove our responsibility to anyone else or everyone else we serve in our clinical setting? Would we be willing to harm all within our setting for the sake of the freedom of one?

My current view of this challenge is that it pits the personal freedom of a smoker against the patient rights of someone else who is seeking services. That is, a smoker does have a personal freedom to smoke. But a different person seeking services in the same setting has a patient right to a smoke-free environment. My view is that at an SUD treatment providing organization, the freedom of one person to smoke ends at the line of the rights of others to access care in a smoke-free environment.

Response #3: The Right to Slowly Die

I usually don’t include any part of this third possible reply, but I’ll present it here regardless.

When I include this, I start by acknowledging the value of the question concerning the individual and their human right to smoke cigarettes. I state that the question is simple, good, and powerful – at the surface level. And I affirm that yes, it is the person’s human right to smoke cigarettes.

And then I introduce the idea that there are potentially complicating matters of law, ethics, and morals. And that similarly, these matters can be phrased as questions as well.

Examples within each category follow.

- Law: Is the person legally permitted to purchase, possess, and smoke cigarettes, or are they under-age?

- Ethics: Has the patient been asked to sign a “Do Not Resuscitate” order in case of heart attack or stroke while they continue to smoke under our care? Have we offered transfer to an “Addiction Hospice” type of SUD care if such a program exists nearby, where dying slowly is the pre-determined plan? Do we realize the implications of the care we do provide and do not provide, and discuss those plainly in our informed consent?

- Morals: Do we offer our staff the standard “Exception From Care” option on smoking-related tasks, and make the related reasonable accommodations? I remind them that “exception from care” is a standard in place so that staff are not required to violate their conscience or personal sense of morality. And I link this standard to the topic of tobacco-free treatment by asking if staff have the Exception From Care option on tasks that require them to actively support or under-treat tobacco smoking as a job function while they are working in addiction treatment?

More to the point, does the patient have a right to die slowly while we watch?

- If it was any other disease, we would do a wellness check, or call an ambulance, or have the person who is allowing themselves to die involuntarily committed as a danger to themselves.

Response #4: Choosing a Human Right or Enacting a Loss of Control?

In this response I note that while picking up their first cigarette ever, the person might have been exercising a choice to smoke.

But to the extent the person now:

- has a persistent desire or inability to cut down or quit smoking

- experiences cravings and urges to smoke

- is losing role function or areas of life due to use

- experiences withdrawal when they don’t smoke…

…it might be that they are not choosing freely but are experiencing a loss of control. And personally, I differentiate loss of control from the notion of a personal freedom.

PART 2: Some possible reasons 480,000 deaths per year due to smoking don’t get our attention or lead to change.

To develop a partial list of some possible reasons our field does not adopt a smoke-free model of treatment, I’ve borrowed some notions from an article3 and applied them to this topic. Below is a list the reader could review toward identifying barriers to this change.

Possibilities might include:

- Allowing smoking is a “residue of the somatic process” still present in organizational leaders, who are current or former smokers.

- Leaders in addiction treatment providing organizations are relatively unaware of how they look on this topic from the outside.

- Leaders in addiction treatment organizations do not discuss their lack of change on this topic in a meaningful way with those outside their organization and prefer to keep it unacknowledged on the social dimension.

- Leaders in addiction treatment organizations take their cues from other leaders in the field; they see other leaders are doing nothing, assume those leaders are thoughtful and intentional, and thus also do nothing.

- Workers and leaders in addiction treatment organizations have a special hindrance that if not present would allow them to obtain a true knowledge of this topic.

- Workers and leaders in addiction treatment organizations, seeking to remain comfortable, enact the process of addiction by allowing it in others, disavow that fact, and attend only to their work tasks.

- When the voice that emanates from within shines light on this matter, that voice is censored, serving to keep the thing out of awareness.

- The charge for personal wellbeing, within organizational leaders, is neither held at the whole person level nor allowed to work progressively over time – but is merely localized within them; thus, their leadership in their own organization is localized by topic.

- Fear of the smoke-free idea, based on fear of the image others would see if the idea was adopted, based on fear of presenting that new and different way of operating to the world at large – and doing passionate self-preservation instead.

- Understanding the smoke-free idea, but not feeling the idea.

- Maintaining the topic at the border between acknowledgment and unawareness.

- The choice to not acknowledge smoking and to take on the problems associated with that choice is preferred over the problems associated with the choice of addressing smoking.

- Maintaining treatment as usual – in its service as a phobic outer structure for an unacknowledged worry.

- The deep knowing that the smoke free approach is the best in reality – but that knowledge is exempted from consideration given the timeless lessons that have taught us avoidance.

- A certain inherited view of making this change, and long ago leaving the idea of this change discarded and unserviceable.

- Adhering to the precious approach with a stilted explanation that does not permit this change.

- Isolation from those that discuss this change with words rather than with emotions and the ideas related to those emotions.

Conclusion: Raising Doubts About Not Changing

We learn in motivational interviewing that raising doubts about the lack of change can help tip the decisional balance. And we learn that providing information can help accomplish that some of the time. Thus, I’ll conclude by providing some information and related resources.

“Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States”.4

“Cigarette smoking causes about one of every five deaths in the United States each year.”4

Smoking is associated with 5 times the risk of relapse 3 years later.5

Severity of nicotine dependence is associated with higher craving in alcohol-dependent patients. This suggests shared pathophysiological mechanisms in alcohol craving and nicotine dependence.6

Tobacco use is correlated with relapse. Addressing tobacco in treatment improves outcomes.7

So, what are some reasons to address tobacco use in addiction treatment settings? And why change to a tobacco-free model of addiction treatment?

- High rates of tobacco use in individuals being treated for other substance use disorders

- Greater morbidity and mortality in individuals who use tobacco and other substances

- Higher relapse rates in patients who do not stop using tobacco

- Patient and staff exposure to second-hand smoke

- Increased risk of new tobacco use, in non-tobacco using patients

In our organizational change process, we went through stages of change over a series of years as an organization. Eventually, we made the decision, including a decision at the emotional level, to get in alignment with both our own values and the evidence – to treat the core disease.

And in so doing, we recognized that cessation might be little more than an attempt to control one’s tobacco use disorder (and that quitting would be diagnostic, not prognostic). And so, we decided to not use a cessation framework, but to use a wellbeing or recovery framework instead.

References

The references are provided in a clickable format for your convenience.

3 Freud, S. (1915). The Unconscious. SE14: 159-215.

4 CDC Tobacco-Related Mortality

7 Stuyt, E. B. (2015). Enforced Abstinence from Tobacco During In-Patient Dual-Diagnosis Treatment Improves Substance Abuse Treatment Outcomes in Smokers. The American Journal on Addictions. 24(3): 252-257.

Recommended Reading

Fiore, M. C., Jaén, C. R., Baker, T. B., et al. (2008). Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, Md.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

Goodheart, C. D. & Lansing, M. H. (1997). Treating People With Chronic Disease: A Psychological Guide. American Psychological Association.

Hilton T. F. & White W. L. (2013). Why Does the Addiction Treatment Field Continue to Tolerate Smoking Instead of Treating It? Counselor. 14:34-7.

Knudsen, H. K. & White W. L. (2012). Smoking Cessation Services in Addiction Treatment: Challenges for Organizations and the Counseling Workforce. Counselor. 13:10-4.

McKelvey, K., Thrul, J. & Ramo, D. (2017). Impact of Quitting Smoking and Smoking Cessation Treatment on Substance Use Outcomes: An updated and narrative review. Addictive Behaviors. 65:161-170.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Alex received his first video game station at the age of two. His love and eventual addiction to video gaming continued throughout his life. It wasn’t until recently that Alex found SMART Recovery, and has made positive changes to his life and began managing his problematic behavior.

In this interview, Alex talks about:

- His dad buying him a VecTrexat two years old

- The progression of gaming systems and how the technology over time

- The “water cooler” conversations around new video games

- First realizing that there was an issue with gaming when he didn’t “grow out of it”

- The “Just Say No to Drugs” PSAs being counterproductive in video games

- The opportunity cost of continuing to play video games

- Video gaming addiction characteristics

- Trying other recovery programs, then finding SMART

- The ways SMART talks about addiction and the nuances for helping each person differently

- How the pandemic affected his addiction

- Knowing he can’t keep throwing his life away

Additional resources:

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Forward – Robin Horston Spencer, MHS, MS, MBA, OWDS, RCAT is in long term recovery since 1991. She has done so very much for her community. She is well known for her collaborative efforts with churches, agencies, 12 Step communities and even ballroom dancing! Presently, she sits on several advisory boards locally, statewide, and nationally. She is the proud mother of a son, Leigh James, daughter-in-law, Malika, and two beautiful granddaughters, Jazmin and Jordan Horston, all of Columbus, Ohio.

With over twenty years in human services, Ms. Horston Spencer worked for 16 years exclusively in SUD recovery support services. She received her master’s degree of Science in Human Service (MHS) from Lincoln University, the United States’ first degree-granting historically black college and university (HBCU) where she was inducted into the Pi Gamma Mu, International Honor Society in Social Science and was awarded the Rose B. Pinky Award for Outstanding Contribution in the Human Service Field. While attending Lincoln University she wrote “Training Recovering Individuals with Criminal Histories to Become Advocates and Mentors.” Ms. Horston Spencer was one of the first in Pennsylvania to become a Certified Offenders Workforce Development Specialist (OWDS) and is a certified Recovery Coach Trainer (RCAT). In addition, she has a MBA and MS both from Carlow University. Ms. Horston Spencer helped form one of the first recovery community organization in Pennsylvania. She served as Executive Director of Message Carriers of Pennsylvania until it turned the lights out in July 2021.

I have known Robin for over twenty years. I recall first seeing her at meetings twenty years ago that the state supported to design a recovery-oriented system of care. Robin has long been a passionate and vocal recovery advocate in Pennsylvania. She loves our system so much; she says what is on her mind and the truths of her experiences. Year in and year out, over the years I watched her get marginalized by our system. Her name would come off of workgroups, her organization left in the margins. The things she had to say made some people uncomfortable. She asked difficult questions. She got excluded and sidelined for being candid. Her funding evaporated. It happens to others, and it leads to a system in which people learn only praise is acceptable. Such systems become profoundly impaired. We can’t heal our people until we address these issues, even as raising them makes a person unpopular. We cannot fix the things we hide in the dark.

We should never have lost the first African American run Recovery Community Organization in Pennsylvania. How did this occur in a time when funding and support for other things in our field are so bountiful? By removing the voices of persons and organizations who express constructive criticism, we only guarantee that nothing will change. It will take real courage and self-examination for leaders to fix this. The first step in changing something is acknowledging it, the second step is genuinely supporting its healing. There is a lot to be done if we are to heal these wounds.

During our interview, Robin shared with me a story of how in the early 1960’s, she had a brother who was killed by a drunk driver. The insurance company compensated her family for the loss of this young boy’s life with a $12 check. $12 for the loss of a human being across an entire life span. I have no idea what that kind of pain feels like. I listened and shared with her that I had learned about this kind of anger and hurt by often being the only white person in a room of African American men coming out of our jails and prisons. They did what I had done to get drugs but served sentences for crimes I never even got charged with. They were treated differently because of the color of their skin. Not something I have ever faced. As Robin noted in our conversation, “I wake up black every day, I don’t get a break from this.” This is of course, was not my life experience, but I can listen and support her voice. I can interview her. I can have the courage to also tell the truth about a system I am dedicated to helping fix. We hope our systems have the courage to listen with an open heart nd to work with us collaboratively to fix it.

I cannot fully understand what Robin feels like having experienced being discounted and excluded, but I have had the experience of being removed from the table. As a person in recovery with hundreds of thousands of hours of professional and decades of lived experience, I have found myself openly discounted or ignored when the things I had to say made people uncomfortable and promised opportunities that shift like a pea under those cups as those cups are moved around on the table. It can be debilitatingly painful. It makes me very angry. It also helps me understand to a small extent what Robin and members of our African American recovery community experience in a myriad of ways that I have never had to face. These voices must be heard. It is the first, but not the final step in healing.

- Tell us about yourself, your recovery, and your work to support recovery over your lifetime?

In 1989, my journey into recovery started for me by a “nudge from a judge.” I got caught transporting drugs across state lines between New York and New Jersey. I spent four nights and five days in a jail in Hackensack NJ. I had never been in prison before, it felt like a lifetime sentence. I had no prior conviction record. My father was there to support me. I really had no idea what was going on or even the chance I was being afforded by this judge. He handed me the brass ring of a pretrial intervention and he sent me to an outpatient in Pittsburgh near where I lived. I had no idea what an outpatient was. I didn’t figure out what a gift I was handed by that judge until a very long time later.

Readers who do not have lived experience with addiction and recovery may not entirely understand, but I was focused on doing what I was doing. Addiction works like that. I did not want any part of recovery. As we often do, I just rolled with what I was asked to do and started figuring out how to get around the obstacles to using, which was my focus. I had to come in for urine testing and ended up handing in samples that would show negative. I attended the services they offered and the recovery fellowship they sent me to, but I wanted no part of those people. I just sat in the back. Eventually, a counselor did an observed UT and I got caught. I then stopped using cocaine and shifted to drinking, as we often do.

This went on for about two years. I did not see myself as “one of those people.” I was not that bad. I had a car. I had a house. I had a job. My family loved me. I would listen to what people said and pick out the differences and not what we had in common. I was just doing what I need to do to stay out of jail. For a long time, it seemed to work.

Then one day, on June 10th, 1991, I was sitting in a 12-step fellowship meeting, and someone said that alcohol was a drug. It had probably been said a few hundred times before that, but in that moment, I heard it. I had a sponsor (in name only). I made the move and called this woman up and asked if she remembered me. Of course, she did. I talked to her about my drinking and my drug history. I had a bottle of E & J brandy in the house, and she suggested I pour it out. Pouring out a full bottle of booze was not in my head at all. She offered to stay on the phone as I did it. I poured that E & J down the sink drain on that day. We talked for hours. This stranger showed me love. She was so happy! I had always been so guarded. She got through my armor. She was an amazing person. She helped me save my life.

I stated to hope a little. I kept going to these meetings and to that outpatient and listening more. I moved my chair further up towards the front of the room. I had not really figured out that I was in treatment. I just liked hanging out with these people and the activities that were offered, like card playing, dances, and picnics. I started to have fun and let my guard down a little more.

Right around this time, I met another woman in recovery. She invited me out to Wexford to hang out and see a movie. It was like an hour away by bus. I still did not fully trust, and I wondered if she was going to kidnap me or something. Her and her recovering friends took me to a movie and bought me popcorn. They would not let me pay for anything. I had the best time ever!

Things started to click. Two years later, I completed that pretrial intervention. A lot of difficult things happened in those next few years, but I stayed on track. My relationship, which had gravitated around using, ended. I lost a few of my family members who stood next to me through my using days. Many of the people who helped me so much in that era are gone now. Six years ago, I lost that sponsor who stayed on the phone as the booze went down that drain. So many people had loved me into recovery. I am so grateful for all they did for me. I have tried hard to pay that debt forward.

- You had an instrumental role in forming and running Message Carriers of Western PA. Looking back what would you want people to know about what brought Message Carriers together?

Keith Giles and Reverend David Else had been involved with Message Carriers before I got there. It was essentially a volunteer organization closely associated with the Center for Spirituality in 12-step Recovery. I ended up getting invited to Virginia as the work with the Recovery Community Support Program (RCSP) grant was getting in gear. Dona Dmitrovic, Denise Holden, Mike Harle, Keith, David, Bev Haberle and Allen McQuarrie were all there from Pennsylvania as well. It was before the focus on recovery really took hold and the slogan, I recall was “Treatment Works,” which was the early slogan of recovery month. It was actually around that time I realized that I had been in treatment. I had not really thought of outpatient in that way. It was more like getting connected to community for me. The slogan became “nothing about us without us” as we all began to come together and focus on recovery.

We were looking at how to establish recovery community affiliates, and Message Carriers became the western affiliate. There were some other people at the time running Message Carriers, one was not in recovery, another one struggled with his recovery. We started organizing rallies and events. One of those events was at city island in Harrisburg. We organized a bus from Pittsburgh and the guy who was supposed to lead it from Message Carriers failed to show up. Dona looked at me and suggested I lead it. At first, I was not sure I could. I was in school and had a lot to juggle. Dona convinced me. She also said she would help. When I had to come out to Harrisburg, she let me sleep at her place. There was a lot of support from within our community and things started to take shape.

- What did Message Carriers accomplish during its operation?

We organized the first recovery rally in Pittsburgh. It was around 2003 and is now known as Pittsburgh Recovery Walks. PRO-A would support ours; we would support theirs. We started to organize the recovery community of Pittsburgh. Over time, we found that our event became a county event and we found ourselves on the outside looking in. That happened more often than not over the years.

Another major success was our prison reentry program. We connected people coming out of the prison system with the recovery community. Nobody else was doing this back then. It took the recovery community to step up and serve our own people. We even had Jan Pringle of PITT PERU independently evaluate the program. She found what we were reducing recidivism by around 80%. The program we put together was successful, yet over time it too ended up moving away from our RCO. Others were funded to run it and we were not. It seems like we came up with many great ideas. When those ideas took shape, the money to do those things went elsewhere. At one point, someone in a position of authority openly acknowledged that our ideas were being used, but as implemented by others.

Message Carriers would put together events, like our Tree of Life event. When treatment organizations would put similar events together, their events got shared across the region. They were supported, but not our RCO. We were always told we needed to get more people involved, or some other excuse. We got lip service, not support.

We all came together in that era and put together the CRS training at PRO-A. It was PRO-A, PRO-ACT, RASE Project and Message Carriers who came together in the offices of PRO-A to set up the credential. It was one of the first in the nation and we began to train people, a major goal of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement. That was taken away too.

You helped me with one of those DDAP grant applications last year. We got a letter saying our submission was rejected. It was the last straw. Every door was shut in our face, time in and time out. That is how Message Carriers closed during a time when our state has more resources than at any other time in history. It was not a lack of resources that closed us. Not one dime got to us. How does that happen, exactly? In my heart, I think they really don’t want recovery community organizations to be supported, it scares them. One run by black people scares them even more.

So many meetings that we were asked to be involved in, but never a penny of support for our involvement. Actions speak louder than words. We were not valued. If we had been valued, they would have found a way to fund us. Since we did not fit in their little box we were consistently left out. It is no accident that that our Recovery Community Organization, Pennsylvania first and for a very long time the only African American run RCO was never really supported and struggled for years until it closed. It is happening to other groups as well. Not one single penny of government support for their work either. What do you think that looks look like to our community?

I became known as that angry black woman. It is true, I am angry about what I saw was being done to us, year in and year out. It was like we would pull things together and then a roadblock would appear. We would submit for a project and then be told we did not have a promise number, so we ended up out in the cold. Maybe next year it would be different we were told. It seemed like monies went to programs who were better politically connected in ways we were not.

They talk about stigma, but then marginalize us because they don’t want more than a media campaign by outside groups. They keep us at arm’s length and under control for a reason. What it looks like is that they only want to acknowledge things on the surface, they do not want to actually dig in deep and deal with it. That makes people uncomfortable. It should, but that does not mean we should not look at it. Message Carriers was killed off because that is what the system wants. It looks like they do not want a strong recovery community, they want control. Being in control of an outcome keeps our system comfortable even as our community members die. That is not okay.

It is like Critical Race Theory. We teach kids that there was slavery in this country, but the lite version. We don’t teach kids about how 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered by a group of white men because his presence in a grocery store upset a white woman. They lynched a 14-year-old boy, and those men ended up with no consequences from our justice system. That was 1955, and it still is happening now. We do not teach this because it makes people really uncomfortable. We know that in recovery, being uncomfortable is part of change. Meaningful inclusion can be uncomfortable for the system. Business as usual is killing our community members. That is an uncomfortable truth. We can’t heal in comfort.

Like Don Coyhis of White Bison once said, the system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets. It is designed for disparate funding and support for recovery community organizations because they do not really want “those people at the table.” Of course, I am an angry black woman. I am angry about what I have seen happen to us. I am angry that my community gets incarceration instead of treatment and we do not fund recovery support provided through recovery community organizations. I am angry that the deck is stacked against us. I am angry that Message Carriers was killed off, death by a thousand cuts. The question is not why I am angry, the question is who would not be if this is what was done to them?

- You have been a major contributor to the recovery movement in your region and beyond over your lifetime. What are you most proud of?

Day in and day out, we showed up to help heal our community, despite the barriers put in our path. Message Carriers was good at supporting multiple pathways of recovery. We have a strong faith-based recovery community in Allegheny County, and we pulled them together. We embraced MAT and the use of medication as a pathway to recovery. We embraced and included the 12 step communities. We brought in harm reduction strategies to keep our community members alive until they could find recovery. We helped our community find their way out of the criminal justice system. In the years I kept Message Carriers going, it touched a whole lot of lives. We helped people find hope and connection, and quite often that led to recovery. Despite our sad ending, Message Carriers has left a huge legacy of restored lives in our community. I want people to know that. I am proud of what we did.

- What would you want young people to know about what you have learned along the way?

It is really important for young people in recovery to study our history. What we have gone through and what we have had to do to accomplish what we have. They need to learn about what happens when we get divided up by those who want to diminish us. They need to learn that we need to focus our systems more on recovery if we want to heal our communities. I want young people to know that we can and do get better, and that the recovery community is vital to that process for so many people.

When one studies our history, there are many difficult times, but we keep moving until things get better. Despite all the barriers, we do get better and then things get better. I would want young people to know that we have to sustain hope for a brighter future. I would want them to know that our systems can and must do better, but for that to happen, we must be at the table in meaningful ways. Anything less is unacceptable.

- What feedback would you have for policy makers on supporting recovery moving forward?

Policy makers need to take a hard look at the system, acknowledge how broken it is and include us in redesigning that system. It must be acknowledged that not funding us is a form of discrimination, and then it must be fixed. The recovery community must have a meaningful role in where the money goes and what is done to heal our communities. We need to pay attention to where the money goes, because it is not supporting things that we need to heal our communities. And we should not have to do “go fund me” campaigns on social media to sit in rooms and participate by sitting at the end of a process once all the decisions are made on where millions of our tax dollars get allocated.

It feels like a bitter pill to me that we fought so hard to create and elevate recovery, believing that this would mean we would get more focus on healing our communities and then experience what I have experienced. Those kinds of things have to be acknowledged and fixed, and not in the way that it has been historically. They say millions of dollars are being spent on recovery, but we can’t see it.

Far too often these kinds of things get wallpapered over and they just move on, pretending there is not an elephant sitting in the middle of the living room. If I did not care, I would sit down, shut up and go about my life. I do care, and I cannot do that. To do so would be a betrayal of all those who came before me. We have come a long way, but we have a long way to go.

- What are your hopes for the next generation of recovery advocates?

It is my hope that they are going to be able to find ways to collaborate together and to not be pitted to fight each other for scraps of funding left on the floor once all the powerful groups get to carve up the lion share of the resources. I would hope that they realize we are being pitted against each other so that we can be kept weak. I want them to know that they have to support each other, or we all lose in the end. It is important for them to understand that we must be united, or we end up with nothing. We must stand together. If the next generation learns that and acts on it, they will accomplish a whole lot.

1. Hope matters in recovery

I’ve been musing a bit recently on the place of hope in addiction treatment and in recovery journeys. Researchers from the USA[1] identified that hope, although recognised as essential for recovery, was not well researched in terms of how it helps recovery progress. They used validated tools (questionnaires) to assess hope and recovery in 412 people. They found that progressing in recovery reduced relapse risk and that hope had a positive mediating effect.

Behavioural change or life transformation?

The researchers suggest that professionals “Consider adopting a holistic approach to addiction recovery that includes factors associated with wellbeing and human flourishing, as opposed to focusing solely on the managing of behaviours. By helping individuals develop a sense of self efficacy (i.e. mastering my illness), clarifying their values, and fostering feelings of connection and belonging, treatment professionals help individuals reduce the likelihood of relapse.”

They go on to stress how important these elements (self efficacy, values, connectedness) are to people who are new to recovery and how by highlighting these, professionals can strengthen their clients’ journeys toward recovery. Key to this is helping to frame recovery as a whole life transformation and not just a behavioural change. (My emphasis)

That feels like a quantum shift from how we come at things currently.

2. Abstinence goals may be more reliable than moderation goals

People asking for help for their drinking problems have a range of problem severities and a range of goals. Both things can be dynamic. Some folk want to reduce their drinking and others want to stop. Some, with severe physical or mental health consequences related to drinking will die if they continue to drink. When we research outcomes from treatment, we tend to look at outcomes that clinicians think are important and less at whether individuals reach their own goals.

In health terms, there’s a consensus emerging that no level of alcohol intake is completely safe, but for most modest drinkers, the risks are felt to be minimal. However, this is evidently not true for people with severe alcohol use disorders. Research has shown that the best treatment outcomes are achieved when people have set abstinence as an end goal, even if moderating drinking was the goal at the start of treatment. My experience from general practice for those with the most severe alcohol use disorders was that initially some – perhaps most – set moderation as a goal, but over a long period, even with maximum support, they moved towards believing abstinence would be safer.

For the kinds of patients I see seeking residential rehab who are at the far end of the severity scale, all have come to the conclusion that stopping drinking represents the best kind of reduction of harms. Many have tried to reduce or control their drinking over years and found that they could not do it in a sustained fashion.

In research[2] from the United States involving 153 people with alcohol use disorder, researchers explored what was going on in terms of the drinking goals the subjects set themselves daily – whether these varied and whether they were able to reach them. They found that complete abstinence was the commonest goal and the one most likely to be reached compared to those aiming for moderation. Paradoxically, they also found that when a daily goal of not drinking couldn’t be reached, those individuals drank more than those setting moderation goals. Nevertheless, the researchers point out:

Abstinence-based daily goals appear to lead to the greatest reduction in at-risk drinking and quantity of alcohol consumption overall.

Pavadano et al, 2022

They say their findings ‘support the clinical benefit of mapping daily goal setting and strategising for specific circumstances’. Of course, this is something mutual aid groups have been practising for decades.

3. Recovery – pulling is better than pushing

Recently I was asked whether getting bad test results (e.g. evidence of poor liver function from blood tests) could act as a motivator to help cut down drinking in someone with alcohol use disorder. I had to be honest and say that in the patient group I see, almost all of whom have biochemical evidence of livers under attack, this was not the case. I said that motivation for recovery generally has to come from hope that things can get better rather than fears that they will get worse.

It was interesting then to have my own observations bolstered by qualitative research[3] from Derby. David Patton, David Best and Lorna Brown explored the part the pains of recovery (push factors) and the gains of recovery (pull factors) play in recovery progress in 30 people with lived experience. Painful things identified included discovering unresolved trauma, difficult housing transitions, moving away from using friends, navigating a new self/world, hopelessness, family difficulties, relapse and stigma.

Pull factors in early recovery related to making new friends in recovery and gaining tools for recovery – mostly in the settings of mutual aid groups. In sustained recovery those ‘pull factors’ were things like: exceeding expectation of what life might be like, supportive romantic relationships, social networks, stable housing, family reconciliation, finding purpose and making progress in employment.

The researchers found that ‘the pains of recovery rarely led to positive changes’ and that those changes were promoted instead by ‘pull factors’.

Their bottom line:

As recovery is neither a linear pathway nor a journey without residual challenges for many people, there is much to be learned about effective ongoing management strategies in preventing a return to problematic use that utilize a push and pull framework

This confirms my impression that when it come to positive change that carrots are generally better than sticks.

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

References

[1] Gutierrez D, Dorais S, Goshorn JR. Recovery as Life Transformation: Examining the Relationships between Recovery, Hope, and Relapse. Substance Use & Misuse. 2020;55(12):1949-1957.

[2] Hayley Treloar Padovano, Svetlana Levak, Nehal P. Vadhan, Alexis Kuerbis, Jon Morgenstern, The Role of Daily Goal Setting Among Individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder, Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports, 2022,

[3] David Patton, David Best & Lorna Brown (2022) Overcoming the pains of recovery: the management of negative recovery capital during addiction recovery pathways, Addiction Research & Theory,

SMART Recovery is excited to partner with iConnectHealth to conduct a robust study determining the relationship between personality type and addiction problems, and to identify which factors may mediate that relationship. The research will also explore the potential benefit of matching mutual help groups and/or treatment orientation with personality types.

The practical benefits we see resulting from this study are an improved understanding of which personality types are attracted to and may benefit most from SMART Recovery, and a way to enhance facilitators’ ability to engage very different types of group participants.

As a thank you for participating, you will receive your individualized De-Stress Rx report which identifies your most powerful stress triggers, symptoms, and strategies for reducing stress.

We are looking to recruit as large a number of SMART Recovery members as possible.

Study participants:

- Must be 18+

- Take the online survey in English

- Have attended (or led) a SMART meeting in the last 30 days

We recently had the opportunity to interview Paul Tieger, Lead Researcher, about the study. He shared the goals and impact they want to make with this study. Click here to listen to the podcast. Click here to watch the webinar.

For questions, please contact: Lead Researcher, Paul Tieger, [email protected]

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Preface: I see a lot of change going on. Sometimes I like to take notes and get things down on paper in an organized way so I can clear my mind and try to make better sense of what I am noticing. This article is that. I share this writing for the sake of the idea that someone else might also be trying to make better sense of things as well.

My starting place is to back up to the idea of a helping relationship. A helping relationship consists of a helper and the one being helped. And that’s no different in the substance use arena.

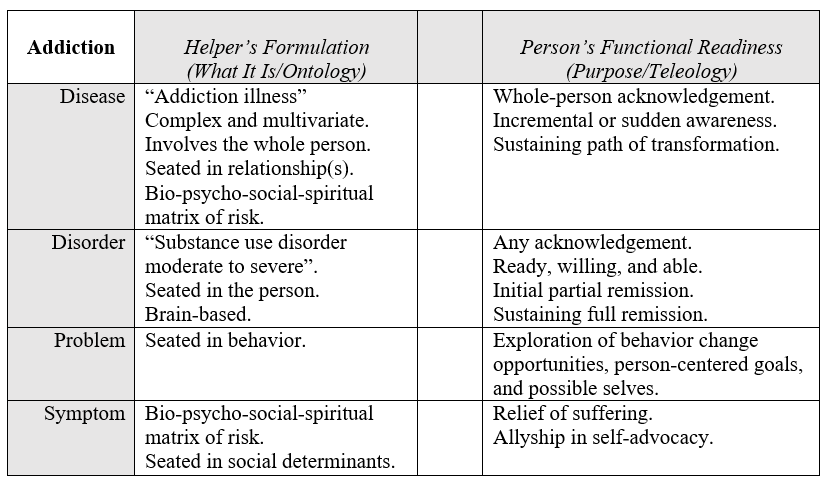

A helper in the addiction arena might view addiction as either a disease, a disorder, a problem, or a symptom.

Meanwhile, the one seeking help might be on a path of whole-person long-term transformation, or seeking total diminishment of their disorder, or exploring options concerning mitigating use, or wanting an ally in their struggles.

When the helper and the one seeking help meet, I wonder if their individual understandings and purposes are a relative match?

And I wonder if we as addiction professionals steer those seeking help and our colleagues accordingly?

Changes in Understanding and Purpose

During the last few decades I have seen an expansion of research and clinical commentary about the nature of substance use problems and their associated helping methods. One result of this expanding effort I have noticed is the development and clarification of differences in how substance use problems are viewed among and between helpers and those seeking help.

And in more recent years, I have seen a rather vastly expanded discourse in academic, research, clinical, public health, policy and other arenas concerning the formulation of what moderate to severe substance use disorders are. What is especially interesting to me is that this development and clarification of differences is within the distinct category of moderate-to-severe substance use disorders – what would otherwise be called “addiction”. That is to say, within the category or concept of addiction, large differences have come to exist in how that more severe and specific problem is generally understood.

Likewise, I have seen a rather vastly expanded discourse in the same literature (and other sources as well) about the purpose of help as expected by and for those who are seeking help.

These differences in understanding addiction, the help being offered, and the help being sought, exist among helpers/helping systems on the one hand, and among those seeking help on the on the other hand. And so naturally there may be a relative match or mismatch of understanding and help between the helper and the one seeking help.

Differences in Understanding and Purpose

Addiction may be understood in vastly different ways. And those seeking help may be ready in very different ways. What are some possible identifiers within these differences? And what recent examples have you noticed?

Below I lay out a framework that shows addiction understood as a disease, or a disorder, or a problem, or a symptom. And for each of those I organize the clinical formulation of the helper and the functional readiness of the one seeking help.

Although working on this was somewhat of an academic exercise, working out this kind of thing helps me at times to organize and clarify what I am aware of.

I’ll say a few things about some of the contents of that grid.

First of all, the open center column is supposed to hold the idea of “matching” like on a test in school. And it’s also meant to show the space within which the relationship happens. Really, what I have in mind is also “mismatching”, of course.

Another thing I wanted to clarify is that in my experience the clinicians that hold the disease model and those helpers more centered in social liberation are the most alike in one key way: the thoroughness of their general awareness.

Thus, I put “bio-psycho-social-spiritual matrix of risk” down for both of those views.

I say that as someone who was academically trained in hardline scientist-practitioner thinking, radical behaviorism, and cognitive-behavioral psychology. That is to say, I know all too well the comparative narrowness underneath the world view that sees addiction as a “disorder” or a “problem”. I will also say that as a result it is hard for me to be sure just how dispassionate I am in what I have included and not included in the grid, especially for the helper side of the “disorder” and “problem” categories.

The column on the right is about purpose, and I decided to add content in that column from the perspective of the person seeking help, rather than from the one providing help. I decided to do that in order to amplify the way a possible mismatch with the helper might manifest. And I decided to limit the content of that column to words centered in what that person might be seeking as well as their functional readiness. Far from complete, these are simple notes to help me clarify my own thinking.

Discontinuity

It occurs to me there may be a relative match or mismatch between the helper’s notion of what addiction is understood to be, and the purpose of the help as defined by the person seeking help. The space within the relationship of helper and person served may be improved or eroded by the fundamental assumptions each of them hold in this regard.

Further, the path or type of help sought by the one looking for help might shift, and this might improve or degrade the match over time.

Even more recently, COVID, various societal forces, and a significant increase in the USA of opioid overdose deaths seem to have collectively brought about a level of considering and reconsidering among many in our profession. And this has resulted overall in a relative stop, break, or discontinuity from the longstanding lineage, understanding, and historical context of our field.

I see the basic content, context, and lineage of understanding in our profession (as it has been seated in our historical continuity and shared in oral tradition, writings, and story) is eroding, And so, in the broader context of the professional part of our field, the former collective understanding of addiction and related helping is now relatively de-emphasized or removed.

And rather, at this moment in time, we are forming new ways of understanding and of helping that began and sit comparatively free-standing in time. It’s almost as if they were brought about and born in a space of discontinuity.

For example, the post-overdose response teams, needle exchange services, and overdose prevention efforts of today (as innovated in the current context) seem quite different to me from the needle exchange and prevention strategies I saw when I stated clinical work in 1988. And they have arisen very recently.

Forming Connections

I’ll leave the reader with some action items to consider that are framed as opportunities.

Rather than attempt to be all things to all people, we could remember to…

- …be more aware of emerging systems of help that are different or new.

- …be professionally and actively linked to newly emerging systems.

- …link helpers from other frameworks to those people they don’t know yet that work elsewhere within those kinds of spaces and kinds of help (so they can meet their peers).

Aside from the readings below, I’ll conclude by linking to an article summary; the reader might be introduced to a leadership style helpful in this context and worth investigating.

Suggested Reading

de Saussure, F. (1916, 1998). Course in General Linguistics. Open Court Classics: Chicago.

Levi-Strauss, C. (1958, 1974). Structural Anthropology. Basic Books.

Denial is a powerful thing. It can make us believe whatever we choose to believe, even though the fac ts stating otherwise may be right in our faces. Denial is an extremely common defense mechanism that our brain produces to help us cope with and rationalize stressful, traumatic, or unpleasant events and experiences in our lives.

ts stating otherwise may be right in our faces. Denial is an extremely common defense mechanism that our brain produces to help us cope with and rationalize stressful, traumatic, or unpleasant events and experiences in our lives.

Although everyone experiences the process of denial multiple times throughout their lives, it is even more common among those struggling with substance use disorder. Think back on times when you were in denial about your use, such as telling yourself that “just a little bit is okay” or “at least I’m doing better than that person.” Often, hiding behind denial was a way to falsely convince yourself and others that things were going well and there were no issues.

Denial can be displayed in multiple ways. Look at some of the most common denial methods and ask yourself if you remember utilizing them when you were in active use:

- Rationalizing: The “just a little bit is okay” mentality. When rationalizing, you tell yourself that you deserve a treat for completing particularly hard or stressful tasks. You believe that using is a justified and deserved reward to yourself.

- Minimizing: The “it’s no big deal” mindset. Making your struggle seem less difficult or intimidating and attempting to brush off fears and concerns. You may realize just how serious your problem is, but simultaneously deny its importance to yourself and others. “I’m only hurting myself.”

- Projecting: The “it’s not my fault” mentality. You project your issues onto other people, blaming them and focusing on what they’re doing wrong instead of what you’re doing right. An example could be placing blame on family or friends for causing you to use.

Now that you have seen and identified with common denial methods, you don’t have to feel bad or guilty. As stated previously, everyone is in denial at multiple points in their lives – and there are many ways to overcome denial, be honest with yourself, and process your emotions and reactions in a healthier way.

- Journaling: Writing down all your thoughts can provide a useful tool for soul-searching and emotional confrontation within yourself. It gives you a chance to let everything out, even your most private thoughts, so that you can be more honest with yourself, and the process of healing can begin.

- Expressing yourself: Don’t keep everything bottled up – speak your mind to others, tell your truth, and be willing to have difficult conversations as a result. Keeping all your feelings hidden can lead to resentment, guilt, or anger, and these negative emotions usually result in denial.

- Attending meetings: By regularly going to AA or NA meetings and keeping in touch with a sponsor, you will be surrounded by a support group of people who are dealing with the same problems as you. You can be completely truthful with them, and they will be able to hold you accountable.

Denial can be tricky and scary but overcoming it can be as simple as surrounding yourself with trustworthy, supportive people and opening up. Living an honest life and dealing with your emotions head-on is a path to successful, sustained recovery.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.