Paul Tieger is the Founder and CEO of Speed Reading People, LLC. He is also a principal of IConnect Health, an international expert on personality psychology, and the author of five bestselling books. Paul currently is the lead researcher for the SMART De-Stress RX Study, which seeks to determine the connection between personality type and addiction issues.

In this podcast, Paul talks about:

- His extensive background in personality psychology and trying to understand who people are

- His most famous case from when he was a jury consultant

- The new SMART study’s purpose is to determine genetic predisposition to addiction issues based on personality type and how SMART can tailor its approach to different people

- Why personality type trumps all other factors like age and gender

- How to prevent confirmation bias

- Dr. Tom Horvath’s enthusiasm for this groundbreaking study

- The three parts of the study the participants will take

- Developing the De-Stress RX personality test as an individualized approach to reducing stress based on the 16 personality types

- The value in receiving personal RX results

- How the COVID era stress has influenced personality types

- How SMART will be communicating how people can participate in the study in the coming weeks

- How to register for the webinar on Wednesday, March 2nd

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

There is and can be no ultimate solution for us to discover, but instead a permanent need for balancing contradictory claims, for careful trade-offs between conflicting values, toleration of difference, consideration of the specific factors at play when a choice is needed, not reliance on an abstract blueprint claimed to be applicable everywhere, always, to all people.

A recent Health Affairs article by Nora Volkow about non-abstinence endpoints for addiction treatments has received a lot of attention. Some are hailing it as a long-overdue change of course and others have expressed concern that it represents a step in the direction of abandoning recovery.

Personally, I don’t see this as an especially noteworthy event for a few reasons:

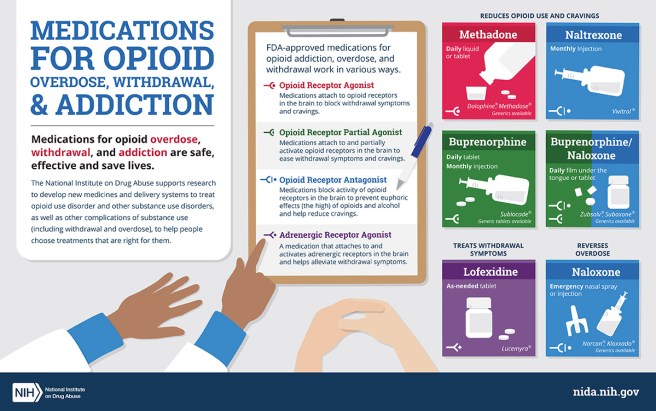

- As linked to in the article, Nora Volkow has called for alternative endpoints nearly 4 years and has advocated for broader use of medication to treat substance use disorders (SUDs) on the basis of non-abstinence outcomes for more than a decade.

- The FDA issued guidance with non-abstinence endpoints years ago.

- The idea that complete abstinence is the metric for medically-assisted treatment (MAT) effectiveness is just not true. I reviewed some of the most frequently cited evidence for MAT and most studies don’t even report information on abstinence.

Different in kind or severity?

The article commits one of my pet peeves by using both “addiction” and “use disorder” interchangeably, without distinguishing between the different kinds and severities of substance problems. This is always important but it seems particularly important when discussing treatment endpoints.

I’ve written at length about how important I believe it is to recognize different kinds of substance problems rather than just different severities and the implications of the DSM 5’s shift from a categorical model of alcohol problems to a continuum model. In short, I believe addiction (the most severe and chronic form) is not just a more severe version of other alcohol and other drug problems, I believe it’s a different category of problem.

However, DSM 5 put all substance problems were put on a single continuum, meaning low severity problems share the same diagnosis as high severity, high chronicity alcohol problems. I see this as akin to rolling all respiratory diseases into “respiratory disorder” as a diagnostic category. The different kinds and categories of respiratory diagnoses have profound implications for determining the prognosis and treatment plan.

For example, for high severity, high chronicity problems (addiction), abstinence has long been considered the most appropriate treatment goal, while moderation has been considered an appropriate goal for low to moderate severity problems. (See here, here, and here for examples.)

Non-abstinence endpoints?

As stated above, non-abstinence outcomes have long been widely accepted as reasons to adopt and expand the use of medications. In fact, those outcomes have become the basis for big federally and foundation funded projects, like expanding low-threshold buprenorphine prescribing in emergency departments.

So… where’s the controversy?

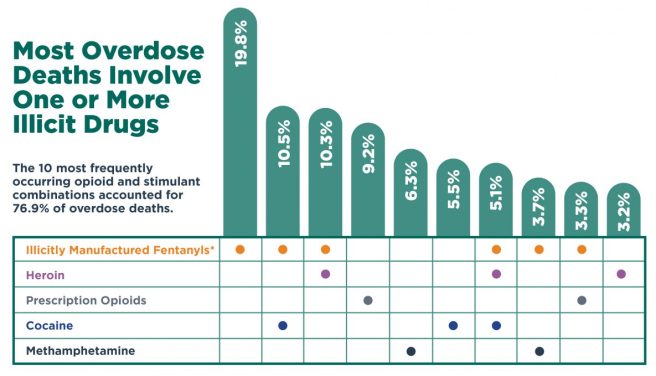

I’m not up on the details of the FDA approval process, but if there have been barriers to getting treatments approved to achieve these endpoints, clearing those barriers is a good thing, particularly in the context of the OD crisis.

First of all, non-abstinence endpoints will align well with the desired treatment outcomes and full functioning for most people with alcohol and other drug problems.

For others, for whom abstinence is necessary for sustained recovery, non-abstinence endpoints may: 1) be useful in the process of determining whether abstinence is necessary for sustained recovery; 2) represent an incremental step toward abstinence; 3) accomplish harm reduction goals; 4) represent one element of a much more comprehensive treatment plan; 5) represent deference to patient preferences.

The OD crisis has increased the stakes, making it clear that we can’t allow the best (for some) to be the enemy of the good. I suppose it’s also possible that an open embrace of these endpoints could result in better informed consent. Some of the tension around non-abstinence endpoints can be attributed to one-wayers who think everyone needs and should only be offered treatments focused on immediate abstinence. However, much more often, I think the tension is related a misalignment between the desired outcomes for patients and families dealing with the high severity/chronicity type, the demonstrated outcomes for the treatment, and the way that information is presented to patients and families.

Looking ahead

So… if non-abstinence endpoints are already well established in research and practice, we’re all set, right? Not quite.

Despite the establishment of these endpoints, there has been some resistance and ambivalence, which I think can be attributed to two factors.

The first is whether they lower expectations for full, sustained recovery. Here, Eric Strain questions whether the field has been ambitious enough on behalf of our patients.

This focus on opioid overdose deaths is overlooking the importance of doing more to help people than preventing a death. Not overdosing is an insufficient endpoint for treatment or for societal and medical interventions – it’s a starting point. We fool ourselves and do a disservice to patients if we allow this to be the measure that allows us to declare success. If a patient with a significant leg wound has the bleeding stopped with a compress, the medical field does not declare victory. Providers clean the wound, stitch it, arrange for physical therapy for the leg, and work to maximize the functioning of the person.

He goes on to call for flourishing as the goal for patients with alcohol and other drug problems.

We should fight to ensure our patients and this field does not accept anything less than flourishing – that should be the goal we bring to our work in research and clinical practice.

One of the major challenges we face is understanding and agreeing upon what’s required to achieve flourishing.

For people with low to moderate severity, eliminating binges or reducing heavy drinking days may be all that is required to make flourishing possible.

For others, like most with addiction, reduced use of opioids will not deliver the improvements in quality of life that they and their loved ones want. Bill White addresses why recovery from addiction can’t be achieved through subtraction of symptoms.

Recovery from opioid addiction is also more than remission, with remission defined as the sustained cessation or deceleration of opioid and other drug use/problems to a subclinical level—no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for opioid dependence or another substance use disorder. Remission is about the subtraction of pathology; recovery is ultimately about the achievement of global (physical, emotional, relational, spiritual) health, social functioning, and quality of life in the community.

Further, for most with addiction, their problem is not multiple distinct substance use disorders like, opioid use disorder, stimulant use disorder, and alcohol use disorder. Their problem is addiction. Treatments targeting individual use disorders too often miss the nature of the problem and set the stage for outcomes where the surgery might be deemed a success but the patient dies.

This brings us to the second factor, distinguishing between patients for whom abstinence is necessary for full, sustained recovery, and those who can achieve flourishing without abstinence.

Dirk Hanson describes how dynamics in the current drug policy and addiction space have made the differences between these types of alcohol and other drug problems fuzzier rather than clearer.

For harm reductionists, addiction is sometimes viewed as a learning disorder. This semantic construction seems to hold out the possibility of learning to drink or use drugs moderately after using them addictively. The fact that some non-alcoholics drink too much and ought to cut back, just as some recreational drug users need to ease up, is certainly a public health issue—but one that is distinct in almost every way from the issue of biochemical addiction. By concentrating on the fuzziest part of the spectrum, where problem drinking merges into alcoholism, we’ve introduced fuzzy thinking with regard to at least some of the existing addiction research base. And that doesn’t help anybody find common ground.

So… as I’ve said above and elsewhere, I think we’d do ourselves a big favor by returning to thinking about alcohol and other drug problems in terms of categories rather than a spectrum. Academics and researchers could do a valuable public service by not using abuse, dependence, SUD, and addiction interchangeably and explaining to readers what type of alcohol and other drug problem they are researching, treating, and discussing.

Why does anyone care about abstinence?

This brings me to another thought about how to move forward.

The spectrum approach has not only introduced fuzziness into understanding the types of alcohol and other drug problems, it’s also introduced fuzziness into our understanding of recovery.

I’m not aware of any historical movement of people with low to moderate severity alcohol and other drug problems identifying themselves as “in recovery”, but academics and advocates have expanded the category to anyone who identifies as once having had a substance problem and no longer does. This, of course, added millions who, for example, engaged in excessive use as a young adult and moderated or quit on their own. This didn’t just add numbers of people to the category of recovery, but changed how recovery had historically been understood.

Recovery had historically been limited to those with the most severe alcohol and other drug problems (addiction) characterized by impaired control over the quantity used, amount of time spent using, and/or whether or not they used. These people had tried moderation and/or eliminating some substances but not others. However, their addiction and it’s hallmark of impaired control made abstinence the only path to full sustained recovery.

This is not a moral decision, it’s a practical decision based on extensive experience and suffering.

This brings me to why I think Volkow’s article got so much attention.

Healthcare and society must move beyond this dichotomous, moralistic view of drug use and abstinence and the judgmental attitudes and practices that go with it.

“Making Addiction Treatment More Realistic And Pragmatic“,

Health Affairs Forefront, January 3, 2022.

The linking of abstinence to moralistic and judgmental attitudes and practices plays into culture war battles that consume too much energy and attention within the field. I don’t think this was her intention, but I think many read it as invalidating of abstinence as an important endpoint and understanding relapse as, not just a disappointing setback, but a serious safety event without any guarantee of restabilization.

I believe the fuzziness around the conceptual boundaries of recovery intensifies conflict around these issues. There was a time when I welcomed researchers and academics focusing recovery. My friend Brian Coon has argued that “recovery” ought to be left to mutual aid groups and proposed that professionals focus on “stages of healing.” I’ve been coming around to the notion that we might be better off focusing on quality of life.

Closing

I fear this has been a meandering and repetitive post, so I’ll summarize here:

- It’s important to recognize and distinguish between the types of alcohol and other drug problems in research, treatment, and professional communication.

- It’s important to recognize that some endpoints (abstinence) aren’t necessary for some SUDs (mild to moderate), AND some endpoints (non-abstinent) will not be compatible with high quality of life for many with high severity SUDs (addiction).

- Further, we can affirm that it is not moralistic to recognize that, for a minority, abstinence is the only endpoint that will allow maximal functioning. (We can also acknowledge that this isn’t grounds for coercion.)

- We might do better to focus on quality of life, flourishing, stages of healing, etc. than on recovery, due to its increasingly fuzzy conceptual boundaries.

- Non-abstinent endpoints can serve multiple purposes that don’t have to, and shouldn’t, replace abstinence as the optimal endpoint for a minority of people with alcohol and other drug problems.

Mindfulness, as described by Jon Kabat-Zinn, means to pay attention in the present moment, on purpose, and without judgement. That’s it.

What this means is that mindfulness is a broad category that includes all kinds of practices that can help you be more present. It is more than meditation, although meditation is a kind of mindfulness. You do not have to limit your practice to meditation, you have lots to choose from and it is uniquely your own. The practice that works best for you might not resonate with your coworker, so experiment. There are tons of apps and YouTube videos that you can explore to help you practice mindfulness.

Here are some suggestions to get you started:

- Focus on your breath.

When you do this practice, don’t try to change your breath pattern—just notice. Be curious about the way you breathe.

- Sit quietly and observe your thoughts.

Practice not attaching to them. Just notice what is coming up for you. If you notice that your mind has wondered and that you are entertaining a thought, return to focus on your breath for a minute or two.

- Eat in a mindful way.

Pick something you particularly love to eat. Pay attention to all of your senses as you eat. What does it smell, feel, look, sound, and taste like when you eat? Do this slowly and really savor each bite.

- Take a walk-mindfully.

Notice all the sights around you. What do you hear and smell? How does the air feel on your skin? Notice your foot touching down and the rate of your gait.

- Listen to your favorite song.

Pick a word of phrase that is repeated several times in the song. As you listen, count the number of times you hear that word or phrase sung.

The latest meditation research shows that while new practitioners can experience changes in their brains that are positive, the real change comes from consistent and longer practice. That’s when you will start to see permanent, and positive changes in the brain, like improved concentration and better emotion regulation.

Your practice can be as long or as short as you want it to be. If you only have five minutes, great, use it!! Most mindfulness experts say that 20 minutes a day is a good amount to shoot for, but make that your long-term goal, and start with realistic amounts of time. In fact, starting with a short practice is a good idea because you will have some early success and will be more likely to continue. Either way, find something you can do regularly and you will start to see the benefits.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

Lately I’ve been working out a practical structure1 for a 5-year model of clinical involvement for patients with addiction illness (not less severe presentations).

What I have in mind is quite concrete but would take a lot of words to say. I am often a visual or spatial thinker, and for this topic it’s true once again.

Suffice it to say the image below shows the starting point of formal clinical engagement (which could be an outpatient or residential program) on the far left, and a five-year path moving forward in time. The example shown is one individual person: the red dots are different problem indicators, and the green dots are different wellness indicators.2

Over the five years, as this example shows, the problem indicators are dropping, and the wellness indicators are rising.3

You’ll notice that even at the very start there are wellness indicators present (specific strengths, assets, resiliencies and so forth). And you’ll notice that out at five years there are also some problem indicators that are still present.4

I showed this to a colleague last week and was asked a couple of questions that helped me see some of my assumptions and blind spots.

One question they asked was, “Why do you have that short wall on the left side?”

I liked that question because it rattled me awake.

- My immediate answer was that it shows the time of admission to a formal primary addiction treatment service (like a residential program or an Intensive Outpatient Program).

- But I loved that question because it basically invokes the idea of the “Engagement/Persuasion” and “Stabilization” phases that I did not show5 and that come before the beginning of the “Active Treatment” phase.

The other question they asked was why I had the long wall there – like, “Why do you show any walls at all, instead of showing just the indicators?”

- The bottom line is that the shape of the two walls (without any other sides) is meant to carry the idea of a system that is both structured in some ways and open in other ways. My classic example of this is how no appointments are needed for some quick oil change shops, but for other work an appointment is made.

In the days ahead I’ll be working out and adding pre-planned service intervals, problem and wellness targets, and continuous personal processes.

And I’ll also be adding some clinical, coaching, and peer support methods to help fill out the function of the model – based on both the pre-planned intervals and the individualized presence/absence of the various indicators.

4https://recoveryreview.blog/2021/04/12/recovery-orphans/

5https://recoveryreview.blog/2020/02/01/peer-support-or-harm-reduction-or-recovery-coaching/

It is great to see this piece coauthored with Ryan Hampton Author of Unsettled published in STAT news

RCOs deserve better than bake sales

Funding for recovery community organizations is a patchwork affair. There has never been an established, stable funding mechanism to support them. Some are funded through time-limited grants, some through block grants to the states, and others rely on grassroots funding drives.

Recovery community organizations are the first groups to help individuals struggling with addiction, but the last to receive funding that translates into healthier communities. They are a huge part of the solution, but can accomplish only so much with self-funding.

Until these organizations are treated with the same respect as other mental health resources, and funded in proportion to their results, overdose deaths will continue to rise. Their reach will remain limited, as will their ability to hire peer workers with lived experience to help people sustain their recovery and enrich their communities.”

Link to Full Article in STAT NEWS

Guest blog by SMART Facilitator Ted Perkins

A new study, conducted in partnership with the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health, confirmed a troubling addiction trend among African Americans. Based on overdose data and death certificates from four states, it found that the rate of opioid deaths among Black people increased by 38% from 2018 to 2019, while rates for other racial and ethnic groups did not.

The recent highly-publicized overdose-related death of African American actor Michael K. Williams was a grim reminder of how drugs and alcohol can strike down even the most successful Black artists and entertainers in the prime of their life. This is not just a loss of life, but a loss to our culture and society. As we all know, addiction is not just a private concern; it robs all of us of our friends, family members, and beloved icons as well.

For Black History Month, SMART Recovery would like to honor and remember those African American artists and entertainers we’ve lost to addiction over the years in the hopes that their struggles can inspire anyone to seek out the help they need to overcome their own addictions.

BILLIE HOLIDAY – 1915 – 1959

“Lady Day” as she was lovingly called, was an iconic jazz and swing music singer with a voice as vibrant and unique as her personality. She got her start grabbing quick singing gigs in Harlem nightclubs in the 30s, and by the age of 20 had landed her first recording contract. She achieved widespread popularity and success in the two decades that followed. Sadly, Lady Day suffered from a heroin addiction possibly exacerbated by mounting legal and financial troubles. She served prison time, and was under arrest in her hospital bed when she passed away from cirrhosis of the liver in 1959. A film was made last year about her life called The United States vs. Billie Holiday available to stream on Hulu.

PRINCE – 1958 – 2016

Prince’s talents knew few bounds. A true polymath, he was able to play every instrument and record his own music. He had dozens of #1 hits, sold over 150 million records, directed and starred in films, created his own videos, and wrote and produced hit songs for Sinéad O’Connor, Chaka Khan and Sheena Easton. Prince was famous for his over-the-top stage performances, but unfortunately over time they caused physical injuries that required pain medications. Sadly, he died from a Fentanyly overdose in an effort to address his pain. Prince never stopped recording, and may have written well over 1,000 songs in his all-too-brief lifetime. There is no telling how many more top-ten hits, films and concert performances were cut short by his opioid addiction.

MICHAEL K. WILLIAMS 1966 – 2021

There are few better examples of an individual using grit, determination, and talent to rise to the heights of film and television fame and critical recognition. Raised in the projects in Brooklyn, he enrolled in theater classes to stay out of trouble. Poverty and intermittent homelessness never slowed him down, and after careers as a backup dancer and model, Williams scored his big break by landing the role of Omar Little in HBO’s The Wire. He went on to star on Netflix’s acclaimed series Boardwalk Empire and was also nominated for a Primetime Emmy for his work on the HBO Biopic Bessie. He transitioned easily to films and had supporting roles in Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave and Gone Baby Gone. Sadly, his is another promising career cut short by Fentanyl.

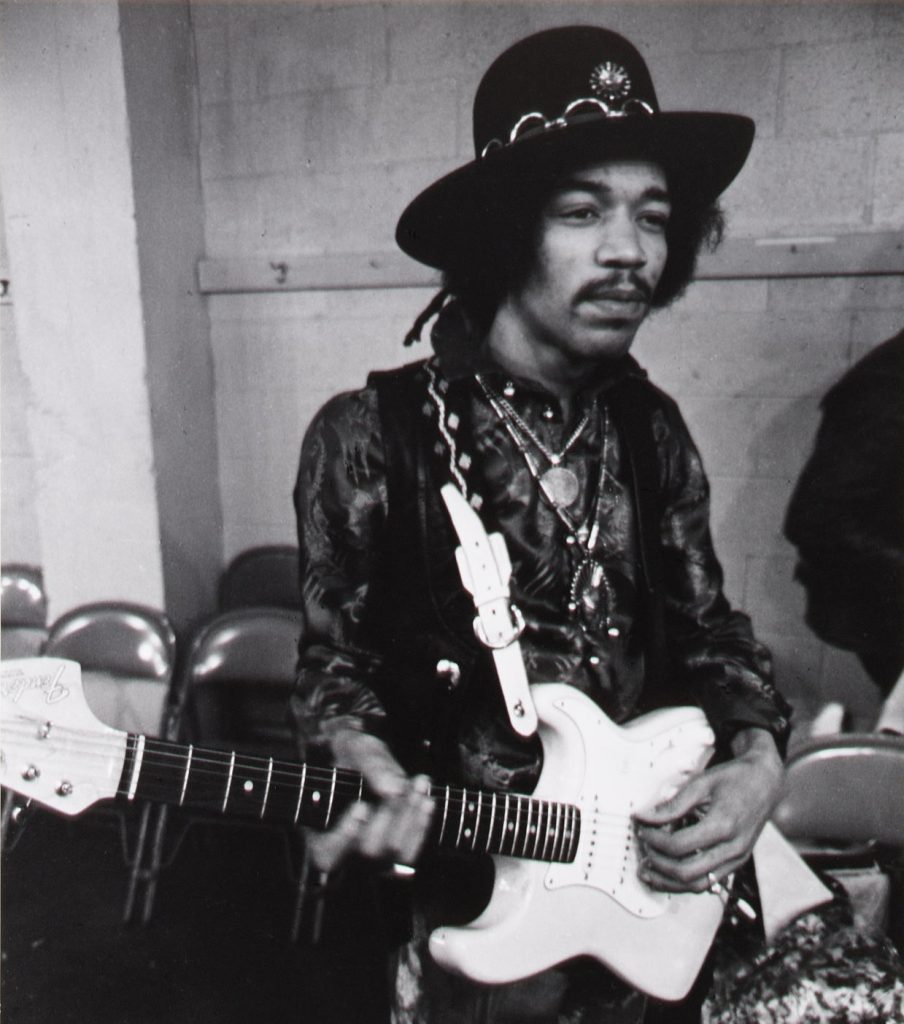

JIMI HENDRIX 1942 – 1970

Hendrix changed rock and roll forever and inspired countless rock guitarists from Jimmy Page to Prince to Eddie Van Halen. While his iconic concert performances and commercial recording success are well known, Hendrix was also a pioneer in the field of audio engineering and recording. He popularized sound effects few of us ever knew existed, like fuzz distortion, Octavia, wah-wah, and Uni-Vibe. While most other musicians turned down their amplifiers to eliminate gain, Hendrix used it to create rock music masterpieces. Hendrix’s life was cut short at the tender age of 27 due to barbiturates. Had he survived, there’s no telling how many more amazing songs and performances he would have given the world.

WHITNEY HOUSTON 1963 – 2012

Houston’s battle with addiction was widely reported in the years before her premature death in 2012 due to atherosclerotic heart disease exacerbated by cocaine use. Only 58 at the time of her death, she had already sold over 200 million records and recorded countless #1 hits. Dubbed “The Voice”, Houston also starred in blockbuster films including The Bodyguard, whose title song I Will Always Love You became the bestselling song by a female artist of all time. We could not possibly do justice to Houston’s amazing career and contributions to music and entertainment here, except to say that she is sorely missed.

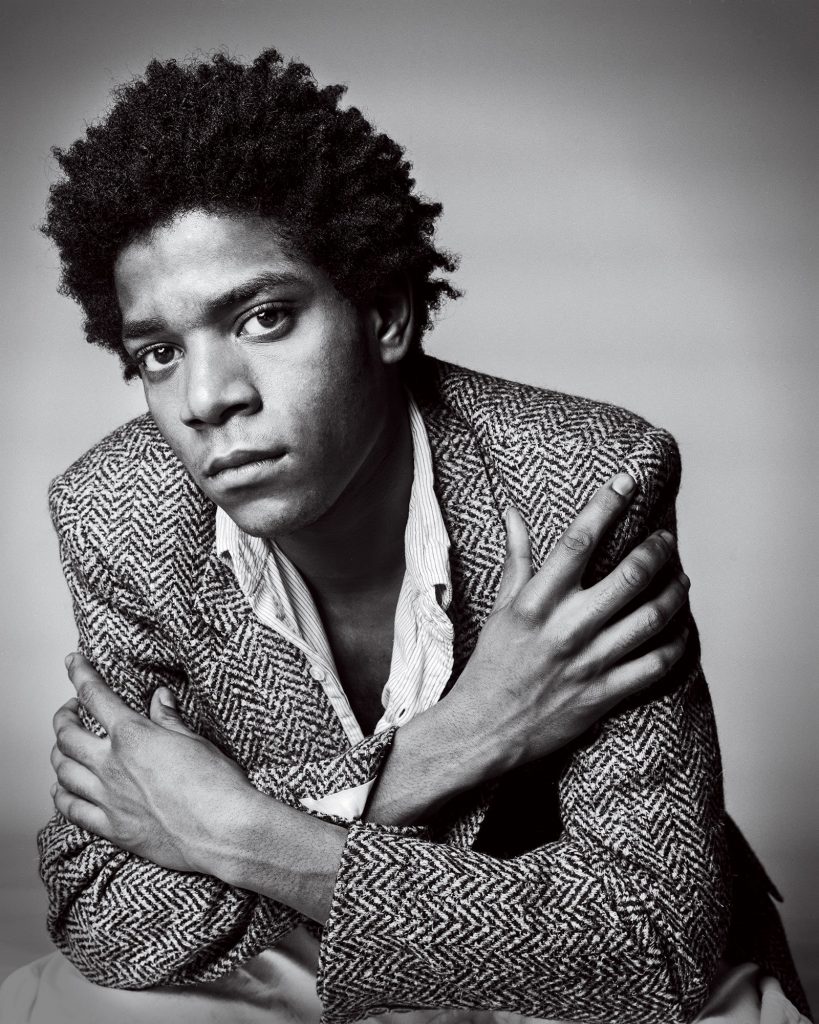

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT 1960 – 1988

A fresh, vibrant and transformative vision in the art world, Basquiat brought graffiti into the mainstream in the 70s, and helped pave the way for the rise of hip hop in the 80s and 90s. His paintings didn’t only show things, they said things about income inequality, segregation, even mindfulness. He was barely into his 20s when his works were on display in major museums around the world. Sudden fame and the death of his close friend Andy Warhol are cited as reasons for why he may have turned to heroin. Although he tried methadone treatments to achieve sobriety, he lost his life to a heroin overdose at 27.

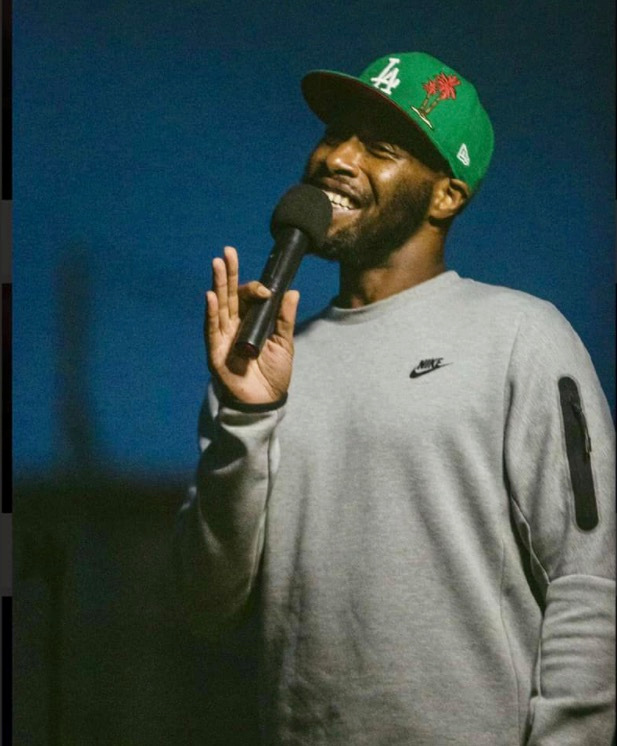

FUQUAN JOHNSON 1979 – 2020

A rising star in the comedy world, Johnson perished along with two other entertainers at the hands of a fentanyl-laced cocaine overdose at a Los Angeles party just a few months ago. Fellow comedians were quick to eulogize Johnson and pay tributes to an entertainer who had a blazing career ahead of him.

Sadly, there are many more Black artists and entertainers whose lives, careers, and positive contributions to the arts and humanities were cut short due to addiction. We’re all familiar with the tragic losses of Michael Jackson, but let’s not forget Franki Lymon, David Ruffin of The Temptations, Donnie Hathaway, and many, many more.

Celebrity or not, any death due to addiction is an avoidable tragedy, and SMART Recovery continues to work every day to motivate and inspire anyone who needs help to recover.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Recently here on Recovery Review Jason Schwartz has been posting some fairly interesting new material, as well as re-posting older material, about the idea of addiction as a disease.

The material he has shared has grown interesting enough and produced enough thoughtful conversation on various platforms, that I wanted to share a version of my very first post on Recovery Review (from 10/21/2019). It pertains to the topic. Over the next few days I might post one or two more that are relevant to this topic Jason has highlighted.

Earlier today, Bill Stauffer posted important and interesting content about the elimination of the classic diagnostic categories separating problematic use and addiction, their replacement with a simple list of criteria, and the relative uncertainties associated with the meaning (if any) concerning the number of criteria for SUD that may be met. That post can be found here.

That post reminded me of conversations I have had over the years with Norman Hoffmann concerning what Norm calls “The Big 5”.

“The Big 5”

Norm has both published, and presented at national conferences, his work concerning what he calls “The Big 5” substance use disorder (SUD) criteria from the DSM-5.

In short, Norm has examined the relative weight of each of the 11 DSM-5 SUD criteria, separately, as applied to the probability of having any one or more additional positive criteria for SUD (from data collected on thousands of consecutively incarcerated individuals).

The empirical questions and answers on The Big 5 as Norm has presented them are summarized here:

- Question: Which of the 11 DSM criteria for SUD are commonly found among individuals with no SUD diagnosis?

- Answer: Tolerance, and Use in dangerous situations.

- That is to say, in his sample, the presence of tolerance as a single factor did not make it more likely than not that any additional criteria were present – and the same was true of use in dangerous situations as a single factor.

- Question: Which of the 11 DSM criteria for SUD are commonly found among those with mild to moderate SUD?

- Answer: Unplanned use, Time spent, Interpersonal conflicts, and Use in spite of medical/psychological conditions.

- Question: Which DSM criteria for SUD are found primarily in severe SUD’s?

- Answer: Efforts to control/cut down but unable (rule setting), Craving with compulsion to use, Failure to fulfill role obligations, Activities given up or reduced, Withdrawal.

- That is to say, in his sample, the presence of any one of these 5 criteria, separately, was more likely than not to be present among 6 or more total positive SUD criteria for any one individual.

In presenting these results from his research, Norm has asked if perhaps the total constellation of The Big 5 is what is commonly called the disease of addiction. Interestingly, Norm has also noted the individual may fit mild or severe characteristics (aside from DSM scaling), based on The Big 5, and as a result he has expressed the following questions:

- Are those with mild to moderate DSM ratings without any of the Big 5 able to moderate use with less intense and briefer services?

- What are the implications of The Big 5 for etiology and course of illness of the individual?

- Specifically, do those that are positive on 2 or more of Big 5 in fact require initial residential placement and/or more intense and longer care, and require abstinence – even when not numerically “Severe” according to DSM-5?

Overall, Norm encourages the clinician to consider the pattern of positive criteria, in addition to the mere total number of criteria present.

Guest blog by Kareem Starkes – J #56138

My name is Kareem Starkes, I am 47 years old and have been incarcerated in California since 1998. My sentence is 60 years to life. This sentence is a result of California’s “Three Strikes and You’re Out” law.

I have a prior felony conviction history consisting of one prior juvenile adjudication at age 17 and one prior adult felony conviction at age 20. The present conviction is my second adult conviction. The juvenile adjudication counted as a strike, resulting in my being sentenced per the three-strikes law.

From 1998 until 2009, the atmosphere in California’s prisons was extremely violent. This violent prison culture was fostered by both the inmate population as well as correctional staff. California’s prison system was then the California Department of Corrections (CDC) without the “Rehabilitation,” which was added after the federal government intervened. It became the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) because the federal government cited CDCR’s overcrowding as constituting cruel and unusual punishment for its inmate population. As a result, rehabilitation programming began to become more prevalent within CDCR’s institutions.

Personally, I have been in the “precontemplation stage” of change from the very beginning of this present term of incarceration. Conditions within the state prisons where I was incarcerated were such that violence was a day-to-day reality, and it was extremely difficult to consider anything aside from daily survival and prevention of being assaulted and/or killed. I chose a mentality of “go along to get along” as a means of my own survival. It was a choice that I made and lived out for almost 17 years of this term until both time and circumstances brought me to a place where I could no longer deny the necessity of my having to change.

My process of positive growth and transformation began in 2012 at the age of 36. It was then that I began to seek help and to do so by availing myself of the rehabilitative programming being offered within the institutional settings. Through rehabilitative programming, coupled with seeking to strengthen my spiritual principles and values and relationship with God, I began the process of self-exploration and assessment.

I began to embark upon the journey of deeply reflecting upon my life, in order to identify the points and times where I found myself in desperate emotional states which had negatively influenced my thought process and perspective. I began to identify why I chose to ultimately adopt self-destructive thinking that led to many of the poor choices and decisions that I have made. These resulted in being engaged in criminality and criminal acts that have been harmful to innocent persons, communities, and to myself.

Rehabilitative programming has been my catalyst for the process of positive growth, change, and the transformation I am blessed to have undergone. It continues to be a lengthy process and journey, nevertheless it is a noble and good endeavor that I feel privileged to be experiencing. I am constantly seeking to be engaged with any form of rehabilitative program and/or organization that may provide the knowledge, tools, and life skills necessary for me to be living a responsible and productive life, one that is rooted in my making living amends for all the wrong and harm I have caused others.

I have reached the place in my life where my daily focus has become being in service to others while paying forward the care, support, consideration, and love that so many good people have invested in me throughout my journey of change.

As I continue to endeavor rehabilitative programming, I learned of new and different programs that are available. I came to learn of the SMART Recovery program as a result of a rehabilitative course I engaged in called “Hustle 2.0”. In this course a listing of addiction recovery programs was given, including SMART Recovery. I had never heard of SMART Recovery before seeing it listed in that book. I asked my wife to go online and find information about SMART Recovery. After some investigation my wife was able to send an email to SMART’s headquarters in Mentor, Ohio and they began to communicate with me.

From there I received all the information needed to begin a SMART Recovery meeting. I absolutely love the SMART Recovery program and all of its Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) tools. The CDCR has only one CBT program called Cognitive Behavioral Intervention (CBI), which consists of two in-person group meetings. This CBI programming being offered through CDCR is a very good program, however, it is extremely difficult for interested persons to be placed into the program.

The great thing about the SMART Recovery program is that it is a CBT based program consisting of similar CBT based tools to CBI. The difference between the two is that unlike the CBI program, the SMART Recovery program is designed in such a way that no licensed clinician is needed to facilitate the program. Also, the program structure is such that any interested person desiring to begin a SMART Recovery meeting group may do so by simply following the SMART Recovery format and getting it going.

In this way, more of the population within our institutional community may be given the opportunity to be exposed to and avail themselves of the CBT tools and life skills necessary to bring about positive change. This happens without having to be placed on any waiting list and having their journey and process of recovery put on hold due to administrative determinants and constraints.

I am thankful for having received the support of the SMART Recovery staff I am in contact with. I presently facilitate two voluntary men’s support groups that I have created here at my facility. I am currently in the process of starting an InsideOut: A SMART Recovery Correctional Program® meeting group here at my facility. The InsideOut program is designed for incarcerated individuals. The men here will greatly benefit from the InsideOut program as I already have. Support for the InsideOut group beginning has been phenomenal with our community here, so I’m excited about the journey ahead of beginning SMART Recovery InsideOut here at Ironwood State Prison.

It is said that where one door closes, another is opened. SMART Recovery should be in all of CDCR’s institutions, and I am committed to doing my part in making this a reality. As CDCR has become committed to rehabilitative programming, there is absolutely no reason why SMART Recovery meetings and InsideOut are not at the top of CDCR’s rehabilitative programming list! Let’s Go SMART Recovery!

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

“Let us use whatever power and influence we have, working

with whatever resources are already available, mobilizing the

people who are with us to work for what they care about.” – Margaret Wheatley

The title of this post comes is inspired by Margaret J. Wheatley, Who Do We Choose To Be?: Facing Reality, Claiming Leadership, Restoring Sanity (2017). The book came up in a recent conversations I had with Phil Valentine of CCAR when we were talking about influential readings. He told me about it and suggested to me it was to be digested slowly. I am an avid reader and sat down to read it from cover to cover. The truth of his words became clear to me after a few pages. Wheatley talks about how all things – even societies, have life cycles and that ours was in a period where large scale change is not often viable. Our institutions have decayed in the current stage of our society that they are largely ineffective at broad systemic change.

She suggests focusing locally and developing leaders to create space to support healthy community. I confess to not yet having finished her book. Having read books like Putnam’s Bowling Alone, The Fourth Turning by Strauss and Howe and Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed by Jared Diamond the topic is not new, but her focus (as far as I can see from about one halfway in) is to encourage leaders to develop and support community in ways that nurture people through difficult times. She calls these spaces “Islands of Sanity.” Quite a lot to digest. I will read it slowly.

Many of us have experienced and are building such Islands of sanity in the recovery community. Two weeks ago in Punta Gorda, Florida the CCAR Multiple Pathways of Recovery Conference was such a gathering of people from around the nation to nurture recovery community. I had a similar experience last Fall at the Mobilize Recovery convening in Las Vegas. The Association of Recovery Community Organizations through Faces & Voices of Recovery is another similar space. A theme of the conversations with people at these events is what do we do next to support additional recovery communities – I would call islands of healing around the nation. I think history has a few lessons for us on what works:

- Communities can and do best self-define their own manners of healing. One of the well-known stories I have heard Don Coyhis, founder of White Bison and the Wellbriety Movement talk about is a conversation he had with federal grant officers when his organization was initially awarded funding to support recovery for indigenous peoples over twenty years ago. He was told he had to use evidence-based practices in the grant. He noted that the Native American community had several thousands of years of evidence of what worked to heal their communities. Much to their credit, they listened not just to Don, but to other recovery community organizations in including their own expertise in strengthening their own communities. In this way, these grants helped form these islands of healing across America through the SAMHSA the initial Recovery Community Support Project grants. These are community up, not government down solutions that can greatly benefit from the support of the government but must be led by the recovery community. Look at what was accomplished, the approach worked. CCAR and many other RCOs who formed at that time are evidence of this very dynamic.

- If we want to build community-based services that meet the needs of our recovery community, we have to design funding around what works for these communities instead of trying to adapt healing processes to existing funding mechanisms. Recovery history shows us we tend to move away from community-oriented solutions as programming becomes institutionalized. We shift to fee for service funding models focused on individual units of care, following a clinical mentality. Instead of developing a deep understanding of what actually works, community-oriented programing is thus altered to meet existing funding mechanisms. These funding processes tend to favor large entities not grounded in recovery community. Community based recovery organizations try and use these funding mechanisms to serve their missions, but it often becomes a challenge as the focus becomes chasing these limited dollars and narrowing their missions to get paid for service units designed for clinical services.

- There is great interest in the national recovery community to build additional communities of healing. Many of my conversations with leaders nationally end up focusing on what we can do to advance efforts to heal communities using a recovery community up model. As I have mentioned in prior articles, I see a lot of room for consensus, but that the development of such consensus involves deep conversations, inclusivity and a lot of active listening. Readers of this post inside of government seeking ways to address our burgeoning addiction epidemic would do well to follow the wisdom of leaders like Dr. H. Westley Clark and the first grant officer of the SAMHSA RCSP grants Cathy Nugent who worked to bring these communities together and to start building these bridges of healing communities by listening to their experiential evidence of what works and helping to support them instead of redefining them to fit into some other model.

There are many of us across the county invested in building a care and support system that actually meets the needs of our respective communities. When I see the depth of interest in this issue, it brings me hope. Our mutual well-being will be largely dependent on how we can help nurture each other’s islands and support new islands built by people focused on healing their own communities. In a post titled Creating a Broad & Inclusive Recovery Plank I recently suggested that developing broad goals is a good place to start strengthening such bridge building efforts.

Perhaps we should form a recovery island bridge building coalition of similar minded communities that want to understand and develop common ground in between our islands and build bridges that span our differences. Here are three points to start such a conversation:

- Recovery communities are the experts on what is needed in their own communities. Recovery communities are diverse, and our efforts must be supported and funded equitably designed by us to serve our own communities.

- Discrimination and stigma against us must end. Systems that tokenize us are perpetuating discrimination. It is not acceptable to tokenize our voices. There has to be an accounting for how this has happened historically to marginalize us in order for healing to occur and for our society to reap the full benefits that a recovery orientated model of care can offer.

- How we do things matters. Our recovery communities are quite often vulnerable, and there are many groups, including some run by people in recovery that take advantage of our own people for material gain. We must establish a shared set of values and ethics and adhere to them to protect the most vulnerable among us.

So, to all the bridge builders of islands of recovery community – let’s find ways to develop consensus and understanding of each other and our experiential wisdom. If you disagree with my three points, I would love to hear yours, if those of us invested in bridge building listen to each other in this way, we will identify a common pathway forward!

It is true that when we come together, we are stronger. It is also true that the history shows us that we are most effective when we do so, even as there are so many forces that keep us arguing over small things. The truth is we do not need to have strong institutions to build consensus and community, we can do that with and for each other.

Please consider being a bridge builder between recovery communities, the island you strengthen may well be your own!

I watched an informational video about search patterns used by the Coast Guard and gained some thoughts I decided to share. The video was just under 30 minutes long and you can find it right here if you’re interested.

As you read this article, see what you notice from outside our field that could serve as hints to help improve our clinical work as addiction professionals.

What are we looking for and where is it heading?

The video I watched showed how Coast Guard search and rescue teams vary their search patterns and their use of search assets (ships, planes) according to:

- the type of object they are looking for;

- the size of object;

- the height and amount of visible surface area of the object above the surface of the sea;

- and “drift”.

As an example, they noted a person wearing a life jacket will float differently from a disabled flat-bottom boat.

Interestingly, they said that drift of the object will vary according to the total of the ocean current at the surface, the deeper current, and the wind. And they clarified that the different currents and wind might each be flowing in the same direction, or different directions.

To me all of that was fascinating and I started to consider possible areas of application for our work. Among other things, I asked myself things like: “As addiction professionals, what is it we are looking for and why? And where is the patient heading?”

Is our work complicated enough? Are we letting science help us?

The search crew stated that all the relevant data about the different currents and the wind are put into a computer. And the software then generates a tailored search pattern for that specific scenario. And the pattern is given to the air assets, ships, and personnel conducting the search.

- They stressed that different things float differently, and the atmospheric and ocean currents and conditions also differ.

- And they stressed the fact that all the relevant Coast Guard staff experience standardized training, so they will all understand the same things and follow the same procedures.

Again, I started to think about our work. Among other things, I wondered if we have made our work complicated enough, and if we as a field are really letting science help us like we could.

Best-practice, structured methodology? That also champions the patient?

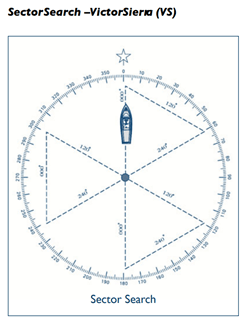

In the video, the “Victor Sierra” search pattern was featured.

The Victor Sierra search strategy is used to look for a small object in a relatively small location where the probability of the object being within that location is relatively high. The pattern is built from 3 isosceles triangles. It was initially odd to me, but rather interesting.

https://ccga-pacific.org/files/library/Chapter_9_Search.pdf. Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

During the use of the Victor Sierra search pattern, one of the crew is assigned to look out the left side of the vessel, one the right side, and one out the front – visually covering the entire search area in a thorough and reliable way.

But before the search begins the direction that the object is moving in is determined. And the direction is determined from the combination of the wind and both shallow and deeper currents.

That combination is used to understand the movement of the object being searched for, and also for a buoy they call the “datum”. The datum is placed in the water and left free to float and move on its own according to the wind and currents – just like the object being searched for.

The word “datum” is fascinating to me because it indicates a single reference point. The presenter noted that in engineering “datum” is the reference point from which one measures other things.

http://wow.uscgaux.info/Uploads_wowII/070/SEARCH_and_RESCUE-A_Guide_for_Coxswains_May_2020.pdf Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

But in this case the datum is literally a moving thing, not a fixed or stationery thing. And its motion (direction and speed) are the sum of the wind, shallow current, and deep current.

They went on to say that the search vessel’s initial motion is always in literal line with the movement of the datum.

Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

Interestingly, once the datum is deployed in the water, the ship backs away from it – in order to not effect it or its movement. The angles of the search pattern are then followed at a fixed rate of speed, at a set distance for each, and completed in a certain order.

As I watched the video, I saw many metaphors related to our work. And I asked myself many questions. For example, “Do we have a nationally-normed, universally applicable, best-practice structured methodology to guide us? One that champions the patient as the center?”

How person-centered are we?

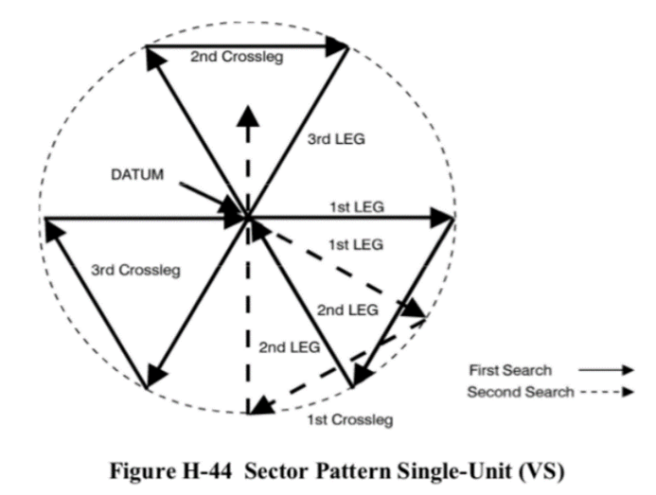

Interestingly, the order in which the segments of the search are completed is static, but that order does not complete one full triangle at a time.

How is the search pattern followed?

- The first leg of the search starts from the location of the datum and is in the direction of the wind/water as crew can best determine.

- Once that first leg of the search is completed, the next angle is calculated from the location of the end of the first leg.

- Following the completion of this second leg, the ship heads directly back to the datum, and this is not done on a preset or calculated heading. Rather, the crew visually locates the datum and drives straight to it.

- Once they physically reach the datum, the direction/degree/angle of the next leg of the search is then determined.

As the search proceeds in this way, the search pattern is kept integrous by repeatedly returning to the datum, rather than making successive calculations from calculated locations. And in this way each new search angle moves with the natural combined movement of the wind and water.

I personally found the level of structured methodology and intentional freedom in the planned work they describe greatly inspiring.

And I asked myself if it is realistic to anticipate in the future:

- a universally available set of best-practice structured methodologies;

- that champion the patient;

- created for us on a normed basis;

- and specifically tailored to the particulars of the current person and their situation.

I ask myself if we are willing to be guided in the most expert way possible?

Messy inconsistency or a combination of expertise and natural forces?

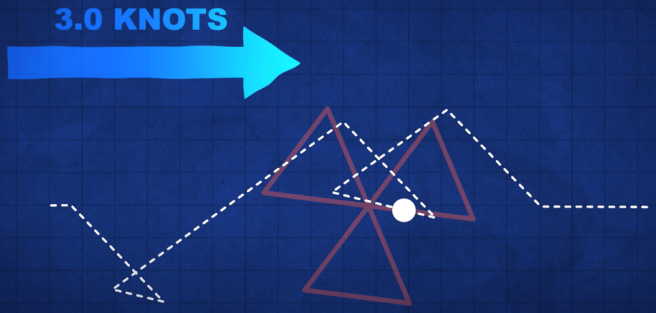

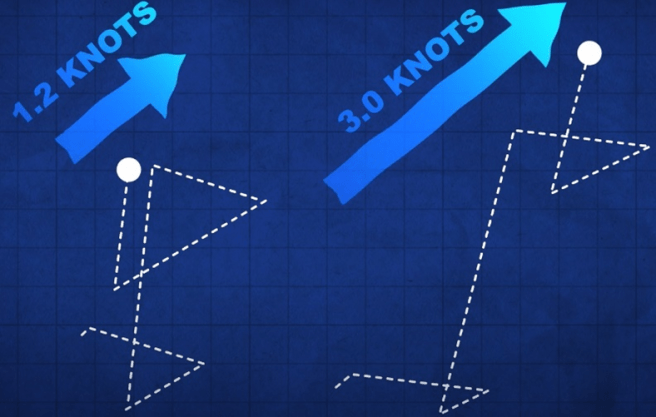

Given drift, the lines that are ultimately searched do not form triangles. This is because the search lines move in time, congruent with the buoy.

By contrast, if the buoy did not move, the course of the search craft would simply replicate the pre-set triangular pattern. But it never does. The actual final shape of the search pattern is non-intuitive and always reflects the actual current/wind.

The shape of the search pattern will differ with the rate of the drift. The search moves with the current.

- For me, the wind is the manifest content of the life of the patient.

- And the water current is the latent content of the life of the patient on both shallower (more accessible) and deeper (less accessible) levels.

- And for me, the buoy reminds me of the person we are searching to help – who is always moving and provides us our center of reference.

This portion of the video made me wonder if we should consider a return to that center each time we complete our immediate purpose, and before we chart our next clinical move.

And it made me think about how our work appears from the outside. For example, does such work reflect messy inconsistency when viewed from the outside? Or does our work trace the combination of expertise and natural forces when viewed from the inside?

Appreciating drift, rescue, and what comes after rescue

The Coast Guard staff informed the film maker that wind and water are often aligned differently or may even be in opposition. They noted that these may all differ from each other due to the differing forces that produce each of them separately. To me, that fact alone is interesting and informs our work.

And they added that the most important task is the first task – determining the “set” and “drift” of the buoy. They stated that “set” refers to the direction of the buoy and “drift” refers to the speed of the buoy.

Once the starting center point of the pattern is established, the direction for the first leg of the 3 triangles is determined by going with the elements, not against them. They also stated that once the speed of the craft is set, it is not changed. Rather they, “Let the current take us.”

- To me this shows us the value of person-centered methods.

And to me this illumines areas of possible struggle for professional workers in our field. For example, do we choose:

- the datum (strictly person-centered reality) as our only reference point;

- the lighthouse that we might need to move toward once the rescue has been accomplished as our reference point; or

- the north star of long-term improvement as our reference point?

Which reference location do we use in the current moment? Or should we combine reference locations? Or at times oscillate between them?

For our work, would we only and always choose the location of the datum as the imagined destination of “full recovery 5 years after the last clinical touch”? Or should we always and only place it and leave it at the epicenter of the person served?

Or could the location of the datum be different, at different times, for different or changing purposes?

- If the epicenter of our work is the person served, then the patient is the reference point.

- If the epicenter is an imagined and much-fuller quality of life, is our effort meaningfully sufficient using that and only that long distance improvement as our only reference?

- But even then, who should define the hoped-for final location, and when, and on what terms?

And speaking of location, what about wind, shallow currents, and deep currents – at the location of the patient’s home or newer waters once they arrive safe? Are we also building safe-harbor locations in our society and larger communities? Do we appreciate all three of: drift, rescue, and what comes after rescue?

Science and compassion?

To conclude I’ll say that I imagine clinical work that includes:

- inputs from the patient, family members, clinical workers, and research scientists;

- reference points including the current condition of the person we serve contextualized by environmental conditions as they are;

- incremental markers to a safe harbor; and

- much farther true-north type wellness goals.

And I imagine our work both moving toward, and rotating on or pivoting against, pairs or groups of these markers (rather than only using one passive reference point) in best-practice algorithms, as we proceed.

Bob Lynn has summarized his aim for our work as “science and compassion”.

Hopefully this article has presented a framework and some considerations inspiring addiction professionals toward that aim.

Suggested Reading

Behavioral Health Recovery Management: A Statement of Principles.

Hofmann, S. G. & Hayes, S. C. (2018). The Future of Intervention Science: Process-Based Therapy. Clinical Psychological Science. 7(1): 37-50. doi.org/10.1177/2167702618772296

Proctor, S.L, Llorca, G.M., Perez, P.K. & Hoffmann, N.G. (2016). Associations Between Craving, Trauma, and the DARNU Scale: Dissatisfied, anxious, restless, nervous, and uncomfortable. Journal of Substance Use. DOI:10.1080/14659891.2016.1246621