A version of this post was originally published in 2018 and is part of an ongoing review of past posts about the conceptual boundaries of addiction, the disease model, and recovery.

The narrative that the opioid and overdose crisis is a product of despair has become very popular. The logic is that people in bad economic conditions are more likely to turn to opioids to cope with their circumstances and that their hopeless environmental conditions make them more likely to die of an overdose. This model frames addiction and overdose as diseases of despair.

This model fits nicely with other writers who have garnered a lot of attention on the internet.

- Johann Hari presents addiction as a product of a lack of connection to others.

- Carl Hart frames sociological factors as causative and argues that there’s a rationality to escaping terrible circumstances via drug use and that a form of learned helplessness eventually takes root.

- Bruce Alexander is frequently cited to support these theories. He did the “rat park” study that found rats deprived of stimulation and social interaction compulsively used drugs, while rats in enriched environments did not.

These understandings are so intuitive, but what if they are wrong?

These narratives make so much sense, and they support other beliefs and agendas many of us hold. Further, it feels like no one is going to harmed by efforts to improve economic, social, and environmental conditions, right?

Well, that’s not quite true. Bill White pointed out that how we define the problem determines who “owns” the problem, and that problem ownership has profound implications for addicts and their loved ones.

Whether we define alcoholism as a sin, a crime, a disease, a social problem, or a product of economic deprivation determines whether this society assigns that problem to the care of the priest, police officer, doctor, addiction counselor, social worker, urban planner, or community activist. The model chosen will determine the fate of untold numbers of alcoholics and addicts and untold numbers of social institutions and professional careers.

The existence of a “treatment industry” and its “ownership” of the problem of addiction should not be taken for granted. Sweeping shifts in values and changes in the alignment of major social institutions might pass ownership of this problem to another group.

White, W. L. (1998). Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, page 338

With so many bad actors in treatment right now, there is not a great rush to protect the treatment industry.

To be sure, we’d be better off of a significant portion of the industry disappeared. However, the disappearance of specialty addiction treatment would be tragic for addicts and alcoholics in need of help.

Further, it just so happens that there’s good reason to doubt the “diseases of despair” narrative.

New study casts doubt on “diseases of despair” narrative

A new study looked at county level data and examined the relationship between several economic hardship indicators and deaths by overdose, alcohol-related causes, and suicide.

Mother Jones describes the findings this way:

Economic conditions explained only 8 percent of the change in overdose deaths from all drugs and 7 percent of the change in deaths from opioid painkillers—and even that small effect probably goes away if you control for additional unobservable factors. It explained none of the change in deaths from heroin, fentanyl, and other illegal opioids.

Rising Opioid Deaths: Is the Cause Economic Despair Or Skyrocketing Supply? by Kevin Drum in Mother Jones

They quote the researcher as observing:

Such results probably should not be surprising since drug fatalities increased substantially – including a rapid acceleration of illicit opioid deaths – after the end of the Great Recession (i.e. subsequent to 2009), when economic performance considerably improved.

Rising Opioid Deaths: Is the Cause Economic Despair Or Skyrocketing Supply? by Kevin Drum in Mother Jones

If it’s not economic hardship, what is it?

Vox describes the study’s conclusions this way [emphasis mine]:

. . . the bigger driver of overdose deaths was “the broader drug environment” — meaning the expanded supply of opioid painkillers, heroin, and illicit fentanyl over the past decade and a half, which has made these drugs much more available and, therefore, easier to misuse and overdose on.

Why a better economy won’t stop the opioid epidemic by German Lopez in Vox

Leonid Bershidsky from Bloomberg noted the following:

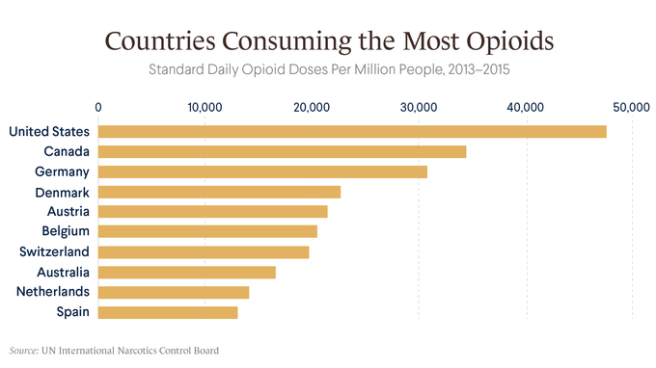

The absence of an opioid epidemic in Europe indirectly confirms Ruhm’s finding. European nations have experienced the same globalization-related transition as the U.S. In some of them — Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, even France — economic problems were more severe in recent years than in the U.S. Yet no explosion of overdose deaths has occurred.

. . .

There’s also a notable difference in what substances are causing overdose deaths. In the U.S., heroin accounted for 24 percent of last year’s overdose deaths. In Europe in 2018, its share of the death toll was 81 percent. That should say something about how supply affects the outcomes.

Supply, Not Despair, Caused the Opioid Epidemic by Leonid Bershidsky in Bloomberg

Piling on

Then, as if to drive the point home, BMJ posted a study examining the relationship between opioid exposure and misuse. They looked at post-surgical pain treatment,

Each refill and week of opioid prescription is associated with a large increase in opioid misuse among opioid naive patients. The data from this study suggest that duration of the prescription rather than dosage is more strongly associated with ultimate misuse in the early postsurgical period. The analysis quantifies the association of prescribing choices on opioid misuse and identifies levers for possible impact.

Brat G A, Agniel D, Beam A, Yorkgitis B, Bicket M, Homer M et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study BMJ 2018; 360 :j5790 doi:10.1136/bmj.j5790

The study “excluded patients with presurgical evidence of opioid or other non-specific forms of misuse in the six months before surgery.” (I would have liked more stringent exclusionary criteria, but it’s still instructive.)

Where does this leave us?

I’ll repeat (a modified version of) what I wrote in a post in response to Johann Hari’s TED talk that emphasized lack of purpose and connection as the cause of addiction and add economic factors to the mix.

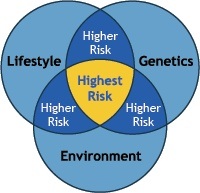

- Do economic/social/environmental factors cause addiction? No.

- Are they important? Yes.

- Do they influence the onset and course of addiction? Yes.

- Do they influence the access and responses to treatment? Yes.

- Is addressing those factors important in facilitating recovery for many addicts? Yes.

- Do economic/social/environmental factors cause addiction? No.

Ok, but what about policy?

This leaves us with some uncomfortable (but obvious, to anyone paying attention to this crisis) findings to consider.

Much of the policy discussion over the last several years has been dismissive of supply as a factor in addiction. This poses very serious concerns about that stance.

I’ve never been dismissive of supply as an important consideration, but I am coming to believe that I’ve underestimated its importance.

A lot of that dismissiveness is in response to the drug war and the moral horror of mass incarceration.

The problem demands more of us than we are typically capable of. We need to figure out how to address illicit and licit supply without resorting to mass incarceration AND assure treatment of adequate quality, duration, and intensity.

Update

A friend shared this Recovery Research Institute summary of epidemiological data on Substance Use Disorders. (I wish they wouldn’t use addiction and use disorders interchangibley.)

The provide data on SUDs by income, education, geography, age, gender, urban/rural, etc. I don’t see support for the disease of dispair narrative in their epidemiological data. Check it out here.

Holly Paulsen says the word SMARToon was coined by a participant in the specialized veterans and first responders (VFR) meetings created a little more than a year ago. It combines SMART and platoon to indicate a large group of individuals working together toward a common goal. And that is exactly what VFR is (with the name including military overtones): a group of individuals using SMART’s practical tools and mutual support to address their addictions–together.

Paulsen is a participant and facilitator in the meetings, and a US Army veteran who served for eight years. She says she started drinking in earnest at age 17 when a local bar near her duty station expressed the belief that “if you’re old enough to serve, you’re old enough to be served.” Real trouble began a few years later when her drinking became a way to self-medicate her untreated PTSD.

Although Paulsen jokes that because her sober date is April 1, 2013, she might advise others that making a major life change on April Fool’s Day is tricky because people might not believe you. But when it comes to helping herself and others through VFR meetings, she is altogether serious. Paulsen loves the meetings, believes in the cause, and, along with the other members of the SMARToon, thinks they’re only getting started when it comes to making a positive impact in the field of recovery.

Paulsen recently answered a few questions about her experience and thoughts about what she is doing.

How long have you been attending VFR meetings?

I’ve attended the VFR meetings since the very first one on November 10, 2020. I was early to a [different] 7:30 EST meeting and happened to see a VFR meeting that I hadn’t noticed before. I figured I’d give it a try—it just so happened to be the very first VFR meeting!

Did you have any concerns before you got started?

Honestly, the thought of having a room full of individuals who understood my unique experiences excited me more than anything. Like any group, I was reluctant to share at first, but the group quickly became my home and the participants, my family.

How have they grown since you’ve been involved?

What started out as one small discussion meeting has grown into three weekly discussion meetings—one of them women only—and a practical tool-time meeting as well. We have aspirations and are making preparations to expand our frequency and reach even further.

What is the most rewarding thing you get out of them?

As our meetings have grown, the number of volunteers that have been spawned from those meetings has skyrocketed. That’s important for SMART’s overall growth. When a member begins to express interest in helping with our meetings, we are always quick to reach out and support them in any way we can through their training. We work better when we work together and we thrive when our members thrive.

What kind of challenges have there been?

I think the biggest challenge for our participants—me included—is asking for and accepting help. Our participants have dedicated their lives to serving others. It’s second nature for us. Being the one in need of support is unfamiliar territory and can be a struggle.

What is an example that illustrates how valuable someone might find the meetings?

Early in the VFR meetings, I began to repeat a quote that I found significant. As a veteran who’s lost countless of my brothers, sisters, and others to suicide, I found the need to reach out to those who may be in crisis and looking for even the tiniest glimmer of hope to hang onto. So, I began stating, “If you’re looking for a sign not to do it, this is it,” on the off chance someone was truly looking for any sign not to end their life. The first time someone reached out to tell us that they had been looking for a sign that night and the words had stopped them, it was a lot to process. To know that someone is still with us today is overwhelming in the best possible way.

What do you hope will happen with the meetings?

In a perfect world, we would love to see a VFR meeting of some kind seven days a week. There is no doubt in my mind that the “SMARToon” will accomplish this. The men, women, and others in our meetings are the most selfless and dedicated individuals I have ever had the honor of meeting. I don’t foresee us stopping there, either. SMART Recovery is global. I see no reason the “SMARToon” won’t eventually be as well. It’s not a dream for us. It’s an eventuality!

With the momentum already established and the people in place to keep it moving, it’s a safe bet that Paulsen and her SMARToon will get it done. Double-time.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

A version of this post was originally published in 2016 and is part of an ongoing review of past posts about the conceptual boundaries of addiction and its relationship to the disease model and recovery.

I’ve had a lot requests to respond to this recent piece in the NY Times.

A Personal Narrative or Universal Model?

The piece is really interesting and engaging description of the author’s personal experience. I get the impression that she’s frustrated that most people would say that her experience with heroin means she has the disease of opioid addiction. She does not believe she has a disease and doesn’t want to be shoehorned into that model. So, she’s offering an alternative framework to explain her experience.

She believes her drug problems were a result of disordered learning, self-medication, and something akin to a love relationship with the relief that heroin provided.

I can imagine it’d be frustrating to be shoehorned into a model that doesn’t fit one’s experience. The problem is that she constructs a model of understanding addiction from her personal experience—an experience that seems fairly atypical—and then presents it as a model for understanding addiction in general.

Addiction as a Category

It’s important to point out that I don’t believe the author uses the same definition of addiction I do. I limit the term addiction to people with chronic and high severity substance use problems characterized by impaired control—most people with drug problems do not have addiction.

In a previous post, I took a long look the categorization of substance use problems. In that post, I made the case for addiction as a different kind of problem from less severe substance use problems rather than a more severe version of the same problem.

Dependence was far from perfect. This is not an argument for a return to the abuse/dependence model. (Though I will argue that we should return to conceptualizing as addiction as a different kind of problem from low to moderate SUDs, rather than a different severity.)

Let’s start by stating that addiction/alcoholism is the chronic form of the problem is primary and characterized by functional impairment, craving and loss of control over their use of the substance.

Problems with the categories of abuse and dependence include:

- Dependence has often been thought of as interchangeable with addiction/alcoholism, but this is not the case.

- Dependence criteria captured people who are not do not have the chronic form of the problem. We know that relatively large numbers of young adults will meet criteria for alcohol dependence but that something like 60% of them will mature out as they hit milestones like graduating from college, starting a career or starting a family.

- Dependence criteria captured people who are not experiencing loss of control of their use of the substance.

- The word dependence leads to overemphasis on physical dependence which, in the case of a pain patient, may not indicate a problem at all.

- The word abuse is morally laden.

- For me, there are serious questions about whether abuse should be considered a disorder at all.

Several of these problems are related to doing a poor job in distinguishing which kind of user the patient or subject is.

The abuse/dependence model fell short in distinguishing between kinds of users. Rather than taking a step forward in distinguishing between the kinds of users, the continuum approach implies that there is only one kind with different levels of severity.

In that post, I also pointed out that framing addiction as a more severe version of the same problem would undermine the disease model.

The continuum approach becomes especially troubling when you think about the idea of giving people with low severity SUDs and people with the disease of addiction the same diagnosis, only with different severity ratings.

There’s little doubt that large numbers of young people on college campuses meet diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder under the DSM 5. I doubt anyone would argue that all of these young people have a disease process? Even a mild one?

This seems likely to undermine the acceptance of addiction as a disease. Not just by the public, but also by insurers and policy makers.

So, it’s not surprising that she’s using the broader definition of addiction when questioning the disease model.

Addiction as a Learning Disorder

I don’t at all disagree that addiction involves disordered learning.

However, I would disagree that addiction is only (or primarily) disordered learning. Addiction is disordered learning AND much more.

The idea that learning plays a role in addiction is not new. The American Society of Addiction Medicine definition of addiction includes the following. (Keep in mind that references to memory speak to learning.)

Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors.

Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Addiction affects neurotransmission and interactions within reward structures of the brain, including the nucleus accumbens, anterior cingulate cortex, basal forebrain and amygdala, such that motivational hierarchies are altered and addictive behaviors, which may or may not include alcohol and other drug use, supplant healthy, self-care related behaviors. Addiction also affects neurotransmission and interactions between cortical and hippocampal circuits and brain reward structures, such that the memory of previous exposures to rewards (such as food, sex, alcohol and other drugs) leads to a biological and behavioral response to external cues, in turn triggering craving and/or engagement in addictive behaviors.

The neurobiology of addiction encompasses more than the neurochemistry of reward.1 The frontal cortex of the brain and underlying white matter connections between the frontal cortex and circuits of reward, motivation and memory are fundamental in the manifestations of altered impulse control, altered judgment, and the dysfunctional pursuit of rewards (which is often experienced by the affected person as a desire to “be normal”) seen in addiction–despite cumulative adverse consequences experienced from engagement in substance use and other addictive behaviors. The frontal lobes are important in inhibiting impulsivity and in assisting individuals to appropriately delay gratification. When persons with addiction manifest problems in deferring gratification, there is a neurological locus of these problems in the frontal cortex. Frontal lobe morphology, connectivity and functioning are still in the process of maturation during adolescence and young adulthood, and early exposure to substance use is another significant factor in the development of addiction. Many neuroscientists believe that developmental morphology is the basis that makes early-life exposure to substances such an important factor.

. . .

In addiction there is a significant impairment in executive functioning, which manifests in problems with perception, learning, impulse control, compulsivity, and judgment. People with addiction often manifest a lower readiness to change their dysfunctional behaviors despite mounting concerns expressed by significant others in their lives; and display an apparent lack of appreciation of the magnitude of cumulative problems and complications. The still developing frontal lobes of adolescents may both compound these deficits in executive functioning and predispose youngsters to engage in “high risk” behaviors, including engaging in alcohol or other drug use. The profound drive or craving to use substances or engage in apparently rewarding behaviors, which is seen in many patients with addiction, underscores the compulsive or avolitional aspect of this disease. This is the connection with “powerlessness” over addiction and “unmanageability” of life, as is described in Step 1 of 12 Steps programs.

Is addiction a disorder of learning? Yes. But, it’s also a disorder of genetics, motivation, reward and stress.

Dirk Hanson has written eloquently on the convergence of thinking of addiction as a learning disorder and muddying the distinctions between problem use and addiction.

For harm reductionists, addiction is sometimes viewed as a learning disorder. This semantic construction seems to hold out the possibility of learning to drink or use drugs moderately after using them addictively. The fact that some non-alcoholics drink too much and ought to cut back, just as some recreational drug users need to ease up, is certainly a public health issue—but one that is distinct in almost every way from the issue of biochemical addiction. By concentrating on the fuzziest part of the spectrum, where problem drinking merges into alcoholism, we’ve introduced fuzzy thinking with regard to at least some of the existing addiction research base. And that doesn’t help anybody find common ground.

Addiction as Love and Self-medication

Addiction as an unhealthy form of attachment or love is also not a new idea. Stanton Peele, a gadfly and long time critic of the disease model wrote the following:

An addiction may involve any attachment or sensation that grows to such proportions that it damages a person’s life. Addictions, no matter to what, follow certain common patterns. We first made clear in Love and Addiction [published in 1975] that addiction— the single-minded grasping of a magic-seeming object or involvement; the loss of control, perspective, and priorities—is not limited to drug and alcohol addictions. When a person becomes addicted, it is not to a chemical but to an experience. Anything that a person finds sufficiently consuming and that seems to remedy deficiencies in the person’s life can serve as an addiction. The addictive potential of a substance or other involvement lies primarily in the meaning it has for a person.

Theories of addiction as a form of self-medication have been about for decades. These theories frame addiction as secondary to another problem which may be social, psychological, environmental or physical in nature.

However, addiction is widely accepted as a primary disease among professional societies.

Further, addiction’s (I’m referring to severe and chronic substance use problems.) onset, course and response to treatment is often affected by social, environmental, psychological and physical problems, but it generally does not fade away when those problems are addressed.

Multiple Mechanisms

The more we learn about addiction, the more we find that there are multiple mechanisms involved. In a 2011 post, I wrote the following (keep in mind that this is abstract speculation rather than a concrete theory):

Or, maybe there are several neurological mechanisms (reward pathway, memory circuits, risk evaluation, self-regulation, stress responses, etc.) and some people may have 2, others may have 6. Some factors may be associated with a more chronic form, others may be associated with a more severe loss of control and overall severity may be associated with the number of factors the person has. (Some might be primary to addiction, others secondary.)

There are probably a lot more than 6 but, for the sake of argument, let’s stick with 6. So, is it possible that the author had 1, or 2 or 3 of these mechanisms (ones involving memory, attachment and learning) while most people with addiction (chronic and severe) suffer from 5 or 6?

Could this provide a way to view her model as true for her (and some others) and the disease model as true for most people with addiction? I think it might. And, maybe it could also shed some light on a portion of that segment of young, heavy users who mature out.

It’s not that she’s wrong. It’s just that she’s zooming in on one part of a larger story to the exclusion of the rest of what we know.

It was suggested to me to post my testimony at the state hearing here. There is a link to a PDF of it at the end of the document

Senate Democratic Policy Committee Hearing

Recovery Issues & Improvements

January 20, 2022, at 10 AM

Testimony on Recovery Funding

William Stauffer LSW, CCS, CADC

Recommendations and Overview of PRO-A & Recovery Community Organizations

I want to thank the Senate Democratic Policy Committee for including me here today. To start, the most underutilized resource we have to support addiction recovery are the thousands of Pennsylvanians in recovery and our grassroots Recovery Community Organizations (RCO)s which are authentic, independent, non-profit organization led and governed by representatives of communities of recovery, who understand and live recovery from addiction every day. Programs like Easy Does It in Berks County, or the PRO-ACT Montgomery County Recovery Community Center. Recovery is contagious – lets fund, support, strengthen, and spread it!

Overview:

- Having run the stakeholder group who made recommendations on recovery house standards, we are concerned that the new recovery house regulations have created conditions in which the thousands of marginalized people who use this housing in early recovery will not be able to afford to live in them.

- As a result of our recent efforts, we are pleased that our Department of Drug and Alcohol has identified through the Recovery Rising that the recovery community has not been funded or included in meaningful ways historically. This encompasses all recovery support services, including how recovery houses are funded and implemented. The Recovery Rising process can improve policy if conducted in truly inclusive ways open to addressing the disparate funding and exclusion of our voices in matters that impact our community.

- While addiction is one of our costliest social challenges in resources and lives, we also know that 85% of the people who reach five years of addiction recovery remain in recovery for the rest of their lives. We should focus on long term recovery as our functional system metric for severe substance use disorders (SUD).

- Policy has focused on short-term treatment and harm reduction strategies, critical, lifesaving elements of an effective care system, yet we have seen minimal investment in community-based recovery efforts. If we expanded investment in long term recovery in ways that meet the needs of the recovery community, we could save more lives, strengthen families, and heal communities.

- Strong, effective policy and interventional strategies are best developed by, and in true collaboratively partnerships with the recovery community organizations that focus on strengthen recovery capital, including recovery housing and other recovery services in these communities and expand our recovery capacity through our statewide recovery community organization.

Recommendations:

- We should independently examine the implementation of the recovery house regulatory standards and their impact on the working poor recovery community that depends on this form of housing.

- Similar to how we support veteran centers and senior citizen centers, we should fund 12 recovery community organizations across Pennsylvania with technical assistance funded and provided through our statewide recovery community organization to strengthen this neglected but critical resource.

- Statewide SUD peer training has been sole sourced by DDAP through a closed door, no bid process, shutting down the marketplace, setting up a gatekeeper model beyond stakeholder input. It has already increased workforce barriers for our whole SUD system and this sole sourced training process should be eliminated.

- Programming for SUDs tends to become punitive, over bureaucratized, and ineffective over time due to the subtle impact of implicit bias that influences how are systems address treatment and recovery needs. The recovery movement in America has focused on reestablishing our roles in these same systems. Our rallying cry, NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT means that no programming should be developed without the full and equitable participation of our recovery community. Elevating and funding RCOs to help develop policy, implement programming, and participate in evaluation would improve care and support for persons with SUDs in ways that reduce discrimination and increase the effectiveness of our entire care system.

Who am I

My name is William Stauffer, I have served in many capacities within our SUD treatment and service support system for well over 3 decades. I am a licensed social worker, certified clinical supervisor and certified alcohol and drug counselor, I teach at Misericordia University and train nationally, including for Faces & Voices of Recovery the national recovery community organization. I worked in and supervised a publicly funded outpatient treatment program for ten years; I ran a publicly funded longer term residential program for 14 years and have served as the Executive Director of PRO-A for 9 years. In 2018, I testified at the US Senate Hearing on Older Adults and the Opioid Epidemic in the Senate Committee on Aging at the invitation of ranking member Senator Bob Casey. In 2019 I assisted organizing and testified at a hearing on the lack of adolescent services in Pennsylvania for the House Human Services Committee and participated in a hearing on the impact of COVID-19 on our service system in 2020. I have written extensively on the recovery in America and how to strengthen our recovery efforts across the nation. In 2019, I was honored at the America Honors Recovery event in Arlington VA with the Vernon Johnson Award as the Recovery Advocate of the year award. I have experienced the loss of close family members to addiction, and I am also a person in long term recovery for over 35 years.

What is PRO-A – The Pennsylvania Recovery Community Organizations – Alliance (PRO-A)

We are the statewide RCO, a 501C3 started in 1998 with a mission to “mobilize, educate and advocate to eliminate the stigma and discrimination toward those affected by alcohol and other substance use conditions; to ensure hope, health and justice for individuals, families and those in recovery.” We have worked collaboratively to develop recovery initiatives across five PA administrations. We have over 5,000 members and membership has always been free. We provide education, training, and technical assistance across the state of Pennsylvania.

- The federal government modeled the very approach that led to the development of RCOs by acknowledging and supporting that people in recovery are the experts on recovery and honoring “community up” solutions.

- 24 states have statewide RCOs similar to PRO-A, many supported financially through state resources.

- We were born out of the national New Recovery Advocacy Movement, predicated on the belief that no policy or service should be developed without the full participation of the authentic recovery community.

- These concepts were historically embraced across our care systems and heavily influential in the development of Recovery Oriented Systems of Care (ROSC) in PA. It established collaborative efforts across several departments of government and with recovery community stakeholders over several decades.

- Peer recovery support services provided by authentic recovery community organizations remain a fundamental element of a recovery-oriented system of care vision in Pennsylvania and beyond.

- We had historically been modestly funded through our state Single County Authority the Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs but have not received any funding through DDAP since FY 2019.

Noted Work Conducted by PRO-A for the State of Pennsylvania

What is a Recovery Community Organization?

A recovery community organization (RCO) is an authentic, independent, non-profit organization led and governed by representatives of communities of recovery. These organizations organize recovery-focused policy activities, carry out recovery-focused community education and outreach programs, and/or provide recovery support services.

- There has never been an established, stable funding mechanism to support recovery community organizations in the state of Pennsylvania across all regions. Instead, funding is patchwork.

- People in recovery understand addiction and have lived experience of recovery. RCOs can support persons, families and communities struggling with addiction by fostering hope, purpose, and connection.

- Resources to fund technical assistance and anti-stigma efforts with state dollars are not being invested in our recovery organizations but instead are flowing out to national organizations or housed within academic institutions with no connection to or knowledge of our experience of recovery and facets of discrimination.

The History and Influence of Recovery Community Organizations

RCOs were funded by SAMHSA in the late 1990s. RCOs have changed the way America thinks of recovery. We introduced the notion of recovery focused care beyond traditional acute care treatment, developing peer support services and recovery messaging to help people move recovery out into the public’s eye. We want a care model to support long term recovery to heal individuals, families, and whole communities.

Until 2018, PRO-A’s collaborative work with our Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs (DDAP) had historically been central to its state plan (page 11):

“Recovery is the foundation of DDAP’s work on behalf of individuals and families experiencing drug and alcohol problems. With recovery as a cornerstone of DDAP’s work, it is essential that we support and promote the statewide recovery organization to ensure that we continually have representation of the faces and needs of the individuals and families that we exist to serve distinct from stakeholders in the direct service arena. It also provides a mechanism to engage and support individuals and groups across the Commonwealth concerned about the issues of addiction and recovery.

Fragmented Recovery Community Funding

Funding for recovery community organizations has historically been quite limited. RCOs that have been able to develop have done so by cobbling together patchwork grants and service initiatives to support their missions. To strengthen recovery efforts, we need sustainable ways to develop and fund these vital community programs

- SAMHSA had long offered grants RCSP on the federal level to support RCOs to develop these models, which have greatly improved how we conceive of recovery and provide SUD care and support in America.

- There has been investment in peer services provided by Certified Recovery Specialist and Certified Family Recovery Specialists through health choices reinvestment dollars and the Center Of Excellence programs.

- Some Single County Authorities (SCA)s have chosen to support recovery community organizations. In their respective communities, we are seeing the benefits of this investment in building recovery capital.

- DDAP has offered several time limited peer service grants offered competitively across Pennsylvania for services to recovery support services, but these grants have largely gone to established human service organizations. They have not been focused on the strengthening of recovery efforts at the community level developed and provided by recovery community organizations steeped in recovery.

- Even as funding has increased, one BIPOC (Black and Indigenous people of color) run RCO that operated for 2 decades closed in the last year for lack of funding and another receives zero support public dollars.

- Grassroot RCOs are often funded through bake sale and spaghetti dinner type funding drives supported by their local community and not within our established care system because funding has not been established for them in a cohesive and sustainable way at the state or regional levels.

- Peer training for Certified Recovery Specialists were initially developed with regional RCOs by PRO-A, our statewide RCO. Last year, DDAP awarded noncompetitive funding to a private organization to take over all peer training in both the public and private sectors. Training for peer workers can now only be done through this new gatekeeper model funded with public dollars. Training requirements can now be changed by this private entity with no input from SUD stakeholder groups creating a system wide workforce barrier.

- The requirements for SUD peer training are perhaps now the most arduous in the nation. They are subject to being changed in ways that impact our entire SUD care system workforce due to this closed-door process eliminating our training marketplace and awarding the facilitation of all public and private training for SUD peer workers to this single entity outside of a system of oversight, checks and balances.

Our Policies and System Orientation Have the Wrong Focus

There is some national recognition that we have failed to focus on flourishing for persons with addiction. In a February 2019 Op-ed for the Journal Alcohol & Drug Dependence, senior editor Dr. Eric Strain noted that “our failure to forcefully advocate that patients need to flourish is tacitly acknowledged through interventions such as low threshold opioid programs, provision of naloxone with no follow up services, and buprenorphine providers who only offer a prescription for the medication.” He suggests that we need to engage patients to support flourishing and provide meaning, a fundamental human need. This is a facet of a recovery-oriented system.

- Research and historic efforts to support wellness has focused on addiction, not on recovery. We need to shift our focus to recovery to heal our loved ones, families, and communities.

- In an Op-Ed for STAT news in early 2020, I noted that “few Americans get anywhere near 90 days of care. Within the confines of existing insurance networks, short-term treatment of 28 days or less is all that most Americans are offered — if they can get any help at all. This ultimately reflects the soft bigotry of low expectations: an inadequate care system designed to deliver less than what people need because we still moralize addiction and do not value people who have substance use disorders.”

- If we want to improve our outcomes, we need to change our measures to focus on recovery and not a single facet of addiction or a short-term outcome.

What is the Five-Year Recovery Paradigm?

The five-year recovery paradigm was started by Dr. Robert DuPont, former Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy and primary investigator of the first national study of the physician health programs (PHPs) which produced impressive long- term outcomes for individuals with severe SUDs. This has evolved into the conception of the “New Paradigm” for long-term recovery with goal of five-year recovery for all SUD treatments including all types of programming and recovery support services with a clear shared goal of long-term recovery. We should focus our efforts across harm reduction strategies, SUD treatment and recovery support services on their ability to produce sustained recovery for persons with severe SUDs.

Focus on Long Term Recovery Outcomes

We should change our lens to focus on long term recovery to strengthen our recovery community.

- “The National Institute on Drug Abuse Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment defines 90 days across levels of care as the minimum threshold of care below which recovery outcomes begin to deteriorate. Of all those discharged from addiction treatment who will resume drug use in the following year, most will do so in the first 90 days following discharge.” Article, Bill White Recovery, the first 90 days.

- An study on the relationship between the duration of abstinence and other aspects of recovery found:

- Only about a third of people who are abstinent less than a year will remain abstinent.

- For those who achieve a year of sobriety, less than half will relapse.

- If you can make it to 5 years of sobriety, your chance of relapse is less than 15 percent.

- What it includes: “The shift to a model of sustained recovery management includes changes in treatment practices related to the timing of service initiation, service access and engagement, assessment and service planning, service menu, service relationship, locus of service delivery, assertive linkage to indigenous recovery support resources, and the duration of posttreatment monitoring and support” From article Recovery management: What if we really believed that addiction was a chronic disorder?

Funding Models – Peer Services vs Funding Recovery Community

We should establish sustainable funding mechanism that nestle recovery in recovery community centers run by recovery community organizations by and for the recovery community.

Funding Recovery Community Centers as a community resource:

- The end goal we should focus on is the strengthening of recovery capital to support long term recovery, which is an effective strategy to strengthen recovery. Recovery capital is the development of all the internal and external resource to support recovery at the individual, family, and community level.

- The best way to strengthen recovery capital is to invest in grassroot recovery community organizations that are focused on the development of these facets at all three levels, individual, family and community.

- We fund community centers and senior centers as community resources and not within the traditional fee for service model because they are community oriented and not a narrowly focused individual service.

The limitations of funding peer services provided as individual or group sessions at the individual level:

- Peer services can support the development of recovery capital at the individual level through existing fee for service models, but these tend to focus only on the individual and not family and community level support.

- The trap of fee for service funding structures is that some grassroot community organizations are often locked out of these provider networks and communities are not able to benefit from what they can offer.

- Even those RCOs who can navigate the fee for service structures end up getting stuck in a funding structure that results in the chasing of low reimbursement rates to stay open while narrowing their effective work to the individual, resulting in an erosion of their capacity to strengthen recovery capital at the community level.

Retooling substance use care to support long term recovery

Addiction is our most pressing public health crisis. The science is showing us that five years of sustained substance use recovery is the benchmark for 85% of people with substance use disorder (SUD) to remain in recovery for life. So why are we not designing our care systems around this reality?

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) identifies that the minimum dose of effective treatment is 90 days, yet far too few people get even that. Negative public perception about people with SUDs underpins much of our system problems – we ration care, regarding persons with SUDs as undeserving. As a result, fewer achieve lasting recovery than could. As SUDs impact one in three families, it is time we recognize these are “our” people and not “those” people and deserve our help. It makes sense and it saves resources.

We have seen that the opioid crisis alone caused a 2.8% reduction in our Gross Domestic Product. Alcohol use disorders still surpass opioid use disorders in annual fatalities. We are talking about a lot of resources spent shoveling up after untreated or undertreated SUDs. Despite these hard facts, we have set arbitrary limits on service, long wait times to access care, insurance denials for care as a norm, and a byzantine process for persons needing help to navigate treatment. People are often served at lower levels and shorter durations of care needed. Ironically, the person often feels like they failed, rather than the system failing to help them.

When a person gets a diagnosis of cancer, our medical system orients care to support multiple interventions, procedures, supports and checkups over the long term. If one approach does not work, we move to another. It is a chronic care model. Such a system is flexible, properly resourced and offers multiple pathways to health. The system coordinates care in a supportive manner through the disease process to get them to the day that they can celebrate five years in remission. This model is the model we need to orient to for severe SUD recovery.

When a person achieves five years in full remission from a SUD, the likelihood of remaining in recovery for the rest of their lives is around 85%. Achieving this standard of care across our service system requires expanding peer services and reorienting care to a long-term service model. It involves treatment assisted by medication, peer support services, family support and case management to help people get back into care quickly in the event of a lapse. People could obtain multiple services based on individual need, typically reducing in intensity over time. In the event of resumption of active use, people can access care in real time with no barriers.

A recovery oriented five-point plan to strengthen and heal our communities:

1. A service system that supports long-term recovery: Establishing and funding SUD treatment and long-term recovery support services that address the needs of the person, including co-occurring conditions/ issues, generally with decreasing intensity – over a minimum of five years.

2. A system that meets the needs of our young people: Develop Recovery High Schools, Collegiate Recovery Programs, and Alternative Peer Groups (APGs). Provide local family education, professional referral, and support programs to assist each young person with a SUD to sustain and support recovery for a minimum of 5 years.

3. Build the 21st Century workforce to serve the next generation: Develop stable funding streams, reasonable compensation, administrative protocols, and peer recruitment and retention efforts.

4. Although there are many social, employment, legal, educational, and other important issues with the person with a SUD, there are a couple of exceptionally important areas. Employment, education, and self-sufficiency are fundamental to healthy recovery and functional communities. We envision a network of employers that provide work opportunities for persons in recovery. We must expand college and trade educational opportunities while reducing and eliminating barriers to employment, like those posed by criminal records, for persons in recovery. There must be simple processes for persons to clear their records from past criminal charges as they attain stable recovery and are ready to become fully productive citizens.

5. Recovery housing opportunities: People in recovery need stable, supportive, and affordable transitional and long-term housing. We must develop a system of quality recovery houses. This system needs to include adolescent and special population housing, infrastructure development, and training for house operators to support recovery from a SUD. The housing system needs to work collaboratively to support long-term treatment and recovery as part of a system of care with a five-year recovery goal.

Link to PDF of Testimony – https://pro-a.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/00-PROA-Senate-Hearing-Testimony-Recovery-Funding-1-20-22.pdf

This post was originally published in 2012 and is part of an ongoing review of past posts about the conceptual boundaries of addiction and its relationship to the disease model and recovery.

In a thoughtful post, Marc Lewis questions the disease model of addiction.

He doesn’t dismiss it out of hand. He seems to look for ways in which it’s right and useful.

It’s accurate in some ways. It accounts for the neurobiology of addiction better than the “choice” model and other contenders. It explains the helplessness addicts feel: they are in the grip of a disease, and so they can’t get better by themselves. It also helps alleviate guilt, shame, and blame, and it gets people on track to seek treatment. Moreover, addiction is indeed like a disease, and a good metaphor and a good model may not be so different.

He offers two objections.

Spontaneous Recovery

First the existence of spontaneous recovery:

What it doesn’t explain is spontaneous recovery. True, you get spontaneous recovery with medical diseases…but not very often, especially with serious ones. Yet many if not most addicts get better by themselves, without medically prescribed treatment, without going to AA or NA, and often after leaving inadequate treatment programs and getting more creative with their personal issues.

My first reaction is that we’re not very good at distinguishing misuse, dependence and addiction. These studies include people who met diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence in college and reduced their use as they moved into other stages of life. The other frequently cited group are heroin dependent Vietnam vets. Again, it’s important to distinguish between dependence and addiction.

So, I think, the problem is not the disease model, but rather, our diagnostic categories and their application. I suspect that if those studies finding high rates of natural recovery limited subjects to those with true loss of control (addiction), the prevalence of spontaneous remission would drop dramatically.

Further, I’m not sure this this is a strong argument at all. Wouldn’t this exclude hundreds of viral and bacterial diseases? These are generally acute illnesses, but don’t other diseases have acute and chronic forms?

Dopamine responses are normal

His second objection is that addiction uses natural brain mechanisms that are shared by many other life experiences.

According to a standard undergraduate text: “Although we tend to think of regions of the brain as having fixed functions, the brain is plastic: neural tissue has the capacity to adapt to the world by changing how its functions are organized…the connections among neurons in a given functional system are constantly changing in response to experience (Kolb, B., & Whishaw, I.Q. [2011] An introduction to brain and behaviour. New York: Worth). To get a bit more specific, every experience that has potent emotional content changes the NAC and its uptake of dopamine. Yet we wouldn’t want to call the excitement you get from the love of your life, or your fifth visit to Paris, a disease.

I have a couple of thoughts about this. First, lots of diseases are characterized by natural body processes turning against the body, many cancers for example. Second, when we’re talking about addiction, we’re not talking about one brain mechanism. (He focused on dopamine release.)

Several brain mechanisms have been identified and, I suspect, better understandings of these will lead to better typologies for AOD problems. Some people may have only one or two of these neurobiological factors, while others have ten. Some factors may be associated with a more chronic form, others may be associated with a more severe loss of control and overall severity may be associated with the number of factors the person has. (Also, some might be primary to addiction, others secondary.)

What is a disease, anyway?

I think the biggest barrier to responding is that the writer did not offer a definition or boundaries for understanding “disease.” Merriam-Webster offers this definition:

a condition of the living animal or plant body or of one of its parts that impairs normal functioning and is typically manifested by distinguishing signs and symptoms

WebMD offers Stedman’s Medical Dictionary’s definition as:

A morbid entity ordinarily characterized by two or more of the following criteria: recognized etiologic agent(s), identifiable group of signs and symptoms, or consistent anatomic alterations.

Is the writer arguing that addiction does not meet these definitions? I’m having a hard time seeing how. And, why does the idea of classifying addiction as a disease bother people so much?

Related articles

Why Mindfulness?

Everyone at one point or another feels weighed down with negative thoughts and internal or external stressors in our day-to-day lives. However, the practice of mindfulness aims to provide an opportunity to put our minds at ease and focus on being in the present moment.

But what are t he true benefits of practicing mindfulness – especially as it relates to recovery? The reality is that mindfulness and recovery can be very closely intertwined, and recovery can often be made more successful by including mindfulness as an active, daily effort.

he true benefits of practicing mindfulness – especially as it relates to recovery? The reality is that mindfulness and recovery can be very closely intertwined, and recovery can often be made more successful by including mindfulness as an active, daily effort.

What are some noticeable benefits of practicing mindfulness?

Mindfulness can improve impulse control by improving the function of the prefrontal cortex. Your ability to “pause,” as taught in the 11th step, will improve. These changes can even be immediate, but practice needs to be consistent if permanent changes are to be made.

Mindfulness can improve one’s ability to manage cravings and triggers by increasing present moment awareness so that you can practice relapse prevention in the moment rather than when you notice that you are really in trouble. If you are practicing loving kindness meditation, it can improve your relationships with others so that you are more helpful and supportive in your recovery relationships.

How does recovery from substance use disorder and mental health go together?

Most people either begin drinking or using to manage their emotions, and eventually keep doing it because it makes them feel better. This need to feel comfortable is a natural human drive that exists without our awareness most of the time. This means that recovery from substance use and mental health must happen together for the best possible chance at success.

Mindfulness is an important tool for regulating emotions, so it can ultimately assist with recovery from substance use. There are also specific practices that can help detoxify the body from both mental and physical effects of substances that will aid in overall recovery. Ultimately, recovery that does not include a focus on improving mental health will not be successful long term.

How can mindfulness connect us more to our bodies?

The body is a powerful tool that most of us are not using to its fullest potential. Mindfulness can improve the connection between your mind, body, and spirit. Cravings and emotions show up on the body before we are thinking about them. Most of us, however, are not aware of these body sensations, and realize we are triggered, craving, or emotional when it gets in our head and becomes harder to fight.

Spend some time thinking about what it feels like on your body when you have emotions, cravings, or triggers. You can train yourself to notice these sensations and then practice some mindfulness or relapse prevention before it becomes too difficult to talk yourself out of how you are feeling.

There are many more benefits that come from incorporating a bit of mindfulness into your daily routine – and it can become a great tool for success in your recovery by helping improve your mental health. Keeping your mental health in check and reconnecting with your mind daily can help yield long-lasting, life-improving results.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The SMART Global Research Advisory Committee (GRAC) invites you to join the first annual SMART Recovery Research webinar series. These webinars are being offered at different times to accommodate the time zones of our diverse Global Research Network. Each webinar will feature members of the SMART GRAC providing an overview of SMART Recovery research to date, updates on the latest research and explore the future of research on SMART Recovery. They are free with registration.

Tuesday, February 15, 2022

11am London | 6am New York | 10pm Sydney

Speakers:

- Dr. Charlie Orton: An introduction to SMART Recovery in the United Kingdom

- Dr. Alison Beck: An overview and update of evidence for SMART Recovery

- Dr. John Kelly: Who uses SMART Recovery? Preliminary findings from a US longitudinal investigation of recovery and health

- Dr. Ed Day: The opportunities for SMART Recovery in the United Kingdom, in treatment and research.

Thursday, March 10, 2022

3pm New York | 8pm London | 7am Sydney

Speakers:

- Dr. John Kelly: Who uses SMART Recovery? Preliminary findings from a US longitudinal investigation of recovery and health.

- Dr. Tom Horvath: Future directions for SMART Recovery research.

- Dr. Alison Beck: An overview and update of evidence for SMART Recovery.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Yesterday’s post and the discussion around it brought up a lot of good questions. Among them was the question, does it really matter whether we call it a disease?

It prompted me to look at some old posts. I’ll share versions of a few of them in the coming days.

A few variations of this have been posted over the years.

How we define addiction determines which helpers and which systems own the problem. The opioid crisis has been moving into medicine (both addiction specific and general medicine), but also into public health, mental health, criminal justice, etc.

Of course, the categorically segregated addiction treatment system has had serious problems with ethics, stewardship, and quality. There’s also no doubt that these debates can turn into turf issues. However, it’s worth considering how a categorically segregated system emerged to determine what should be protected and what can be modified or discarded. How problem definition fits into that history is an important element.

Here are a few thoughts from Bill White on the topic from Slaying the Dragon and some Counselor articles:

On problem ownership:

Whether we define alcoholism as a sin, a crime, a disease, a social problem, or a product of economic deprivation determines whether this society assigns that problem to the care of the priest, police officer, doctor, addiction counselor, social worker, urban planner, or community activist. The model chosen will determine the fate of untold numbers of alcoholics and addicts and untold numbers of social institutions and professional careers.

The existence of a “treatment industry” and its “ownership” of the problem of addiction should not be taken for granted. Sweeping shifts in values and changes in the alignment of major social institutions might pass ownership of this problem to another group.

White, W. L. (1998). Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, page 338

On the segregation-integration pendulum:

American history is replete with failed efforts to integrate the care of alcoholics and addicts into other helping systems. These failed experiments are followed by efforts to move such care into a categorically segregated system that, once achieved, is followed with renewed proposals for service integration. After fighting 40 years to be born as an autonomous field of service, addiction treatment is once again in the throes of service-integration mania. This cynical evolution in the organization of addiction treatment services seems to be part of two broader pendulum swings in the broader culture, between specialization and generalization and between centralization and decentralization. Once we have destroyed most of the categorically segregated addiction treatment institutions in America, a grassroots movement will likely arise again to recreate them.

White, W. L. (1998). Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, page 333

On the historical essence of addiction counseling:

If AOD problems could be solved by physically unraveling the person-drug relationship, only physicians and nurses trained in the mechanics of detoxification would be needed to address these problems. If AOD problems were simply a symptom of untreated psychiatric illness, more psychiatrists, not addiction counselors would be needed. If these problems were only a reflection of grief, trauma, family disturbance, economic distress, or cultural oppression, we would need psychologists, social workers, vocational counselors, and social activists rather than addiction counselors. Historically, other professions conveyed to the addict that other problems were the source of addiction and their resolution was the pathway to recovery. Addiction counseling was built on the failure of this premise. The addiction counselor offered a distinctly different view: “All that you have been and will be flows from the problem of addiction and how you respond or fail to respond to it.”

Addiction counseling as a profession rests on the proposition that AOD problems reach a point of self-contained independence from their initiating roots and that direct knowledge of addiction, its specialized treatment, and the processes of long-term recovery provide the most viable instrument for healing and wholeness. If these core understandings are ever lost, the essence of addiction counseling will have died even if the title and its institutional trappings survive. We must be cautious in our emulation of other helping professions. We must not forget that the failure of these professions to adequately understand and treat addiction constituted the germinating soil of addiction counseling as a specialized profession.

White, W. (2004). The historical essence of addiction counseling. Counselor, 5(3), 43-48

On the risks of diffusion and diversion:

Diffusion and diversion constitute two of the most pervasive threats in the history of addiction treatment institutions and mutual-aid societies. Diffusion is the dissipation of an organization’s core values and identity, most often as a result of rapid expansion and diversification. Diffusion creates a porous organization (or field) that is vulnerable to corruption and consumption by people and institutions in its operating environment. Diversion occurs when an organization follows what appears to be an opportunity, only to discover in retrospect that this venture propelled the organization away from its primary mission.

The current absorption of addiction treatment into the broader identity of behavioral health is an example of a diffusion process that might replicate two earlier periods – the absorption of inebriate asylums into insane asylums and the integration of alcoholism and drug-abuse counseling into community mental health centers in the 1960s. This diffusion-by-integration has generally led to two undesirable consequences: 1) the erosion of core addiction treatment technologies; and 2) the diversion of financial and human resources earmarked to support addiction treatment into other problem arenas.

White, W. L. (1998). Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, page 341

The complexity of addiction requires an equally complex notion of recovery. Holistically, recovery is generally conceptualized across three classes of variables- individual, social, and ecological. The biopsychosocial model of recovery fits well within this framework. Expanding recovery conceptually to include the environmental sphere of variables has allowed for new contextual and structural factors to be incorporated into the study of recovery trajectories. This has been the recent scientific trend. However, itemization of recovery factors across all three classes is ultimately incomplete without establishing what binds these variables together. This article proposes the relational nature of recovery as the theoretical connective tissue which binds together these multidimensional variables across individual, social, and ecological spheres.

Introduction

The working definition from the Recovery Science Research Collaborative (RSRC) states that recovery is an “intentional, dynamic, and relational process” focused on improving wellness (Ashford et al., 2018). The RSRC definition is a synthetic and consensual definition drawn from the leading definitions of the time to operationalize the notion of recovery for recovery scientists to use. As such, this definition is a valuable starting point to theorize aspects of recovery.

The current evolution of recovery science presents an opportunity to consider what makes a recovery successful and how healing can emancipate individuals from destructive patterns and lifestyles. Along with new definitions, new theories allow more inductive ways to consider recovery outside of clinical, medical, and pathological frameworks. Recovery-Informed Theory states that “recovery is self-evident, and is a fundamentally emancipatory set of processes” (Brown and Ashford, 2019). Hearteningly, this theory has promoted an emphasis on personal experiences as a primary source for conceptualizing and studying recovery and has helped relieve researchers of the burden of imposing artificial constructs that are contextually absent of meaning, systems critique, and/or intrusive or destructive to recovery communities.

Since recovery predominantly occurs over the course of years within the daily lives of individuals and is not reliant upon persistent clinical or medical support, recovery constitutes both a lifestyle and a culture. As such, recovery is a social, relational, and identity process, whereby thriving becomes the best predictor of outcomes (Best, et al., 2016; Gutierrez et. al, 2020).

Theories and metrics such as Recovery Capital and the Strengths and Barriers in Recovery Survey (SABRs) denote several life areas that account for the significant variance of recovery success, stability, and progress (Best, et. al. 2020: 2021). The Brief Recovery Capital Scale captures personal and social recovery capital in a unipolar instrument (Vilsaint et al., 2019). The SABRs identify life areas, such as taking care of one’s health and engaging in meaningful activities, that are associated with recovery stability (Best et. al 2021). Criticism regarding the measure of recovery capital involves the ecological or community dimension (Hennesey, 2021). While the SABRs instrument better identifies specific factors that serve as recovery strengths and barriers, such as criminal justice involvement and access to transportation (Best, et al., 2021). However, both of these concepts are missing a critical relational component that needs to be further explored. The reason has to do with assumptions we make about recovery- namely, that intrapersonal, interpersonal, and ecological accounting of recovery supportive resources are as far as scientists can get toward measuring recovery. This of course relates to the idea of observable data and the limits of existing recovery measures.

However, I would argue that while personal strengths, access to resources, and community support are critical for recovery, it is really the individual’s relationship to these features that genuinely tie them to recovery. While the difference may seem slight, adding the relational nuance to our scientific models is critical to understanding why those with access to resources still may not recover, or how those with no access might recover anyway, and why systems seeking to support recovery must go further than simply providing necessary forms of support. In short, we are missing the ties that bind recovery supports together. Let’s take a common example – consider the fact that no matter how helpful one’s surroundings may be, without the desire to recover, little can be done to help a person who is struggling with addiction to get into recovery. This is because the individual and their relationship to their environment have not gone through the necessary shift required to make use of the available resources. Yet it is also unhelpful and potentially harmful to assume the person “just doesn’t want it bad enough” – Something more is needed here, we can bean count recovery resources all day long, but without understanding the relational dimension between the individual and those supports, we will never achieve any true predictive power, scientifically speaking.

The Relational Impairment of Addiction

Any family member who has dealt with a loved one deeply affected by addiction knows the challenges of supporting them. Several models and theories related to the challenges of supporting a loved one struggling with addiction exist, ranging from so-called “tough love” to strategies that use “unconditional positive regard”. While this article is not concerned with debating the pros and cons of various strategies, it is essential to note what is absent but implicit within these interventions- having a relationship with someone in active addiction can be painful, and at times, damaging to the emotional health of family, co-workers, partners, and friends. Furthermore, long-term recovery from addiction requires a re-articulation of relational space, namely developing boundaries, healing relational trauma, and learning new ways to interact with intimate others. At the same time, all the parties involved are ideally focused on the recovery process, both at the personal and relational levels. The need for sustained recovery focus and improvement is integral for the individual who is overcoming problematic substance use and for those concerned about them. Thus, a two-step process occurs, those dealing with a loved one in recovery must heal, alongside, and in cooperation with the individual. Often an entirely new relational format is needed within families, and sitting in on any family treatment session will illustrate. Obdurate and negative relational patterns constitute a huge clinical obstacle, one that requires a lot of ongoing work by everyone involved. Though our treatment systems have yet to fully adapt to healing the whole family, most clinicians understand and even stress the relational component of recovery. Obviously, recovery is not, and cannot be solely about the person overcoming addiction.

“Ideas, emotions, and attitudes which were once the guiding forces of the lives of these men are suddenly cast to one side, and a completely new set of conceptions and motives begin to dominate them” (Alcoholics Anonymous, pg. 27)

The relational aspect within families clues us into the importance of the relational space in recovery. From this, we can expand the idea. If healing the relationships within families is so vital to recovery, what about other relationships? What about one’s general relationship to the world, to society, economy, work, and education? We know these factors are important to recovery, but we have yet to frame the relational space beyond family and friends as equally important to understanding recovery. Addiction negatively impacts virtually all relationships. Not just relationships to people and to themselves. Is not healing one’s relationship to their intimate partner, equally important as healing one’s negative relationship to steady employment, or negative relationship to the Child Support Office, or a negative relationship to the bank and credit card companies? Are not the dysfunctional ties to these institutions and systems a cause for poor emotional health as well? What about when one looks in the mirror? Should they not use the same means of rearticulating their relationship with themselves as they do with their spouse.

The relationship to the self (intrapersonal), to others (interpersonal), and to their ecological field (ideas, institutions, systems, and society), must all be considered of equal importance. On the one hand, we can account for these three areas with certain metrics, but can we account for the relationship between the individual and each of these areas?

Not Just Human Relationships

What other relationships change in recovery? One of the most interesting effects of recovery involves changing relationships to ideas and institutions. One cannot underestimate how much ameliorative potential is unlocked in the re-articulation of the self in relation to the world through the recovery process. Often recovery requires that one let go of their existing views of various social institutions. Take for example a person who is involved with the law. In this case, one’s relationship with the criminal justice system is almost entirely negative. Often there is tremendous resentment towards police, judges, and probation officers. Existing criticism of the criminal justice system in America notwithstanding, if one is to live with an ounce of peace, then they quickly realize that toxic forms of anger aimed at anonymous systems, ideas, and institutions (as flawed as they may be), is a futile waste of precious emotional energy, and to continue to harbor deep senses of anger, hatred, and cynicism set one at an emotional disadvantage in their recovery. Or take a person’s negative relationships with institutions such as marriage, school, political parties, or employers. Regardless of whether one has a justified reason to consider these things in a negative sense, those in early recovery understand relatively quickly that their view of the world must change. This essential shift sets up a new relational possibility – the person comes to understand that rather than taking up the role of Sisyphus, refusing to be happy, or satisfied until such institutions radically change to alleviate their negative emotions, that they might simply reposition themselves either to a position of neutrality, or alternatively, acquiring the skills, knowledge, and capacities to honestly challenge such things down the road. This subtle repositioning often makes all the difference between a life lived in futile exasperation or one of proactive peace and wisdom. Even the Serenity Prayer is explicit on this point.

Relation to Resources, Rather than Resources Alone