Markita Renee had a drug addiction, battled homelessness, and legal problems, but triumphed over all thanks to perseverance and a commitment to her recovery. She made SMART part of that successful commitment. She took the facilitator training and now runs her own meetings.

Find Markita’s meeting information.

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Looking for something fun to do on New Year’s Eve? Then join the SMART Recovery Online community for the virtual, annual New Year’s Eve Around the World! This 24-hour long event rings in 2022 in every time zone.

This nonstop meeting with hourly start times begins at 5:30 a.m. ET on December 31, 2021, and ends at 3:30 a.m. ET on January 1, 2022. Online meetings are laid back and fun with themes selected by that meeting’s host.

What People are Saying

“It is a great resource and support for our participants on an especially vulnerable holiday.”

“Having a place to go at any moment of the day is awesome.”

“You can enjoy SMART meetings and benefit from positive, growth oriented conversation with peers vs other toxic alternatives”

Special Guest Hosts

- Dr. Joe Gerstein – Motivation, Motivation, Motivation!

- Dr. Tom Horvath – Most Helpful Ideas We Have Learned From Our Connection With SMART

- Mike Hooper – What Does Lifestyle Balance Look Like to You?

- Ted Perkins – SMART en Español

How to Participate

This event is free-of-charge. To participate, use your SMART Recovery Online (SROL) login credentials. You can create SROL credentials for free at www.smartrecovery.org/community/join.php, and get access to the event schedule and meeting link(s). *Verifications will NOT be provided*

RSVP on Facebook

Help us spread the news of our free, virtual event with your connections. RSVP to this event on Facebook and share it with friends and family.

You don’t want to miss out on this fun day of community, celebration, and cheer. We look forward to seeing you and ringing in the new year together!

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

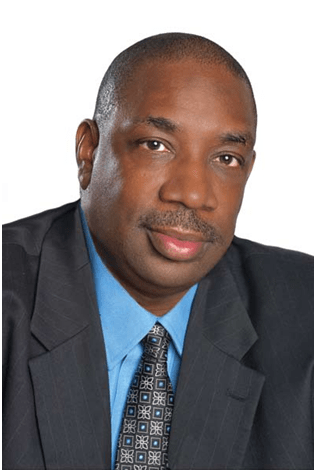

Forward – The first time I had heard about Mark Sanders was when I was preparing for Black History month in early 2013. I wanted to highlight the history of recovery within African American communities in our quarterly recovery newsletter. After initiating an internet search, I quickly found the Online Museum of African American Addictions, Treatment and Recovery which is curated by Mark Sanders. It is a fascinating site with what is easily the most comprehensive history of African American recovery and the contributions of African Americans to recovery efforts ever put together. A resource for historians interested in these topics. What I soon realized is that he was the only person to have compiled and preserve this history to this extent.

I have often written in recent years about the importance of preserving our history and likened efforts to record and preserve our history to a seed bank. A place we store vital seeds to nurture future generations in case something happens to our current harvest. Mark Sanders has created this vault. The entire and most complete record of African American recovery history is in one place and available to the public. What he has done is remarkable and worthy of high praise. We have far too few historians who have undertaken this vital work to preserve, protect and use such information to inform more effective strategies into the future. A whole lot of history is getting lost forever with each passing year.

I have referred to Mark’s online museum over the years to learn about the rich history of recovery in African American communities. I also wonder what would happen if the lights went out in his online museum. What would happen to his life’s work? Would we lose this history? We should heed the adage that one should never put all of one’s eggs in a single basket. I have asked myself similar questions about the life work of Bill White. We need more such historians establishing additional repositories for our recovery history, in all its rich diversity.

On a personal note, every interaction I have had with Mark has underscored a common bond we have in respect to how important our history is and understanding it as invaluable for our efforts moving forward. I am honored that he took the time out of his clearly very busy schedule to talk with me and to participate in this project.

Returning to the seed bank analogy. Seed banks are most effective when there are many of them. If you are reading this and feel inspired, take action. If you see recovery history worth recording and nobody is, it just may be something you are called to do. Learn about and record your own community recovery history and seek ways to preserve that information for the future. I hope you read this interview and check out Mark’s Museum and his written works. Take up the challenge, learn your own community history and use it to inform what you do, how you do it and help mentor the next generation!

- Who are you?

My name is Mark Sanders. I am a licensed clinical social worker and a person in long term recovery for the last 40 years. Recovery is my life work. I have focused on developing policies and process to help people like me get into and to sustain long term recovery in many different roles. I have had a particular focus on recovery efforts within African American communities. I serve on the Great Lakes (region 5) Mental Health Technology Transfer Center Network and on the Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center (Great Lakes ATTC) which is located within the University of Wisconsin. I live in Chicago. I am an international speaker, trainer, and consultant in the behavioral health field and have been honored to have my efforts reach thousands of people across the United States, Europe, Canada, Caribbean, and British Islands.

As a writer, I have authored a number of books, which focus on behavioral health. These include Slipping through the Cracks: Intervention Strategies for Clients Multiple Addictions and Disorders (2011) and Substance Use Disorders in African American Communities: Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery (2013). I have also had two of my stories published in the New York Times bestselling book series Chicken Soup for the Soul. Readers interested in my writings can find a list of all of my publications here.

Among other awards, I have received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Illinois Addiction Counselor Certification Board and the Barbara Bacon Award for outstanding contributions to the Social Work profession as a Loyola University of Chicago Alumni. Recently I was the 2021 recipient of The Community Behavioral Healthcare Association of Illinois, Frank Anselmo Lifetime Achievement Award.

I co-founder of Serenity Academy of Chicago, the first recovery high school in Illinois and was the past president of the board of the Illinois Chapter of NAADAC. I have been a university educator for many decades, having taught at the University of Chicago, Illinois State University, Illinois School of Professional Psychology, and Loyola University of Chicago, School of Social Work.

Perhaps the thing that means the most to me in my efforts to strengthen recovery efforts in the United States and beyond is my work to record and preserve the recovery history within African American Recovery. I am the sole curator of the Online Museum of African American Addictions, Treatment and Recovery, to the best of my knowledge it holds the most comprehensive record of recovery within the African American community ever compiled.

- What would you like people to know about the history of the recovery movement In African American Communities from your perspective as a historian?

There are four distinct eras of our history I would like to emphasis. The first one was right after the American Revolution. There was a temperance movement in America that started at that time because alcohol misuse was pervasive. Martha Washington, the first, first lady of the United States was involved in these efforts that later become known as the Martha Washingtonian or also as the Ladies Washington Society. Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), who played a pivotal role in the abolition of slavery in the United States, was also a leading temperance advocate. Douglass viewed ritualized drunkenness (drinking contests for slaves hosted by slave masters) as part of the machinery of slavery and viewed sobriety as a key strategy in the emancipation and full citizenship of African Americans. In one of his writings, he talked about how alcohol was used to keep slaves in servitude:

“One plan is, to make bets on their slaves, as to who can drink the most whisky without getting drunk; and in this way they succeed in getting whole multitudes to drink to excess. Thus, when the slave asks for virtuous freedom, the cunning slaveholder, knowing his ignorance, cheats him with a dose of vicious dissipation, artfully labelled with the name of liberty. The most of us used to drink it down, and the result was just what might be supposed; many of us were led to think that there was little to choose between liberty and slavery. We felt, and very properly too, that we had almost as well be slaves to man as to rum. So, when the holidays ended, we staggered up from the filth of our wallowing, took a long breath, and marched to the field,—feeling, upon the whole, rather glad to go, from what our master had deceived us into a belief was freedom, back to the arms of slavery.”

Douglass believed that temperance was key to liberation, and he became the first prominent African American in US History to embrace and promote abstinence from alcohol. He used his own story so that others within the African American community would consider abstinence from alcohol.

The second period I would highlight is the 1940s and what happened in Cleveland Ohio at that time. An African American woman who was seeking help for her drinking went to the Akron area for help shortly after AA was formed. Because of segregation, she was not allowed to participate in the meetings, but they gave her a copy of the 12 steps. She went home to Cleveland and started what were known as the Cleveland Friends Clubs. These became gathering places for African Americans in recovery. Our earliest example of African American recovery communities. They held AA fish fries, and AA BBQs, and AA poker nights where people gathered and supported each other into and to sustain recovery. I have met and spoken to people who were around in that era, and they told me that in that era before they understood the 12 steps, recovery was about 90% fellowship and 10% based on the 12 steps.

Chicago also played an important role in our early history. One facet of our local recovery history is the Evans Avenue Club which originated in 1945 and it still is in existence today. Its first anniversary dinner was held at the historic Hull House in March 1946, with 18 people present. The nine Evans Avenue members and nine from other groups. In late 1946, the first meeting outside the homes was held at Friendship House, 43rd and Indiana Avenue. The group met at Friendship House for about three months, then moved to Parkway Community House. Seventy-six years later, the Evans Avenue club is still serving the community.

One of the myths I would most like to dispel is that African Americans do not do well in 12 step recovery. The history above illustrates that fact. I also knew people in our community who were involved in these 12-step based early recovery communities. I am aware of one sponsorship family that came out of this era that still meets for an annual picnic in Lake Geneva with over 200 people attending. 12 step recovery is certainly one of the many pathways of recovery that supports recovery for African Americans.

The third era I would like to focus on is the 1960s. This was a time in American History in which we saw an increase in heroin use across the United States. We also saw an increase in incarceration in comparison to earlier times. You may be aware that Malcolm X was a person in open recovery. His recovery started while he was incarcerated. He was influenced by a man named John Elton Bembry, who Malcolm knew as Bimbi and converted Malcolm to Islam through prayer. Malcolm had a conversion experience similar to Bill W where he saw a bright white light. He then embarked on a practice he referred to as “fishing for the dead.” The goal of this program was outreach to incarcerated African Americans to help them with recovery, employment, and to avoid future incarcerations. I wrote about the parallels that he had with Frederick Douglass and the lessons we can learn from their legacies in a piece I published on the Great Lakes ATTC site titled “Lessons from the Recovery Legacies of Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X” that may be of interest to readers.

Also, in this era we saw the formation of the Black Panthers Party, which was founded in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale to challenge police brutality against the African American community. They saw the prevalence of substance misuse and addiction as a form of genocide. They encouraged people to stop drinking and using drugs. They even later pioneered the use of acupuncture to be used to support detoxification efforts. One of the untold stories in American History is that when the Black Panthers formed chapters in communities, those communities saw a decrease in prostitution, they saw a decrease in drug use, and they saw a decrease in incarceration. When those chapters were forced out of communities all of these problems increased again. I had a brother-in-law who was active in the Black Panthers, and the only time I ever saw him cry was when one of those efforts to eliminate a local chapter worked and they saw a lot of their community strengthening strategies dashed.

The final era was in the mid-1980s, particularly events in 1986. While in 1986 Betty Ford was raising awareness about alcoholism and improving public sentiment about seeing alcoholism as a medical condition a different story was unfolding in respect to crack cocaine. Stimulant use had been on the increase in the early 80s during the era that cocaine was glamorized as a high-end drug. Richard Pryor nearly died while freebasing cocaine. In the years after that, crack cocaine was formulated, with the ether that was used in earlier smoking methods being replaced with baking soda, which made a crackling sound when heated. Cocaine use was increasing at that time across all demographics. Then came the death of Len Bias. He was the second pick on the NBA draft that year. On June 19th, 1986, two days after being selected by the Boston Celtics with the second overall pick, Bias died from cardiac arrhythmia induced by a cocaine overdose. It was a tragedy for such a gifted young man with a promising future.

While this raised national awareness about risks associated with cocaine use. Tragically, that awareness was used to criminalize addiction in ways that had a disparate impact on African Americans who were using cocaine. This occurred through the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 also known as the Len Bias Law, which was signed by President Reagan on October 27th, 1986. The act mandated a minimum sentence of 5 years without parole for possession of 5 grams of crack cocaine while it mandated the same for possession of 500 grams of powder cocaine.

Crack use was more widely prevalent in African American communities than white communities. This 100:1 disparity was one of the drivers of the incarceration of black Americans in America skyrocketed starting in this era. In 1985, there was around 400,000 African Americans incarcerated, in 1995, it has risen to over a million and in 2005 it was over 2 million and in 2015 over 2.5 million. It is hard to overstate for readers who may not know what the consequences are of a felony arrest. You can recover from addiction, but not from a felony, it follows you around for the rest of your life and carries with it huge barriers to living to your full capacity, even decades after people turn their lives around and recover from addiction.

- What influenced efforts to bring together the African American community to support recovery efforts?

There were three factors I want to talk about that related to what brought are communities together. The first was the impact that mass incarceration had on our African American communities. We saw large numbers of people being incarcerated for long sentences – 5 or even 30-year terms. It broke up families and impacted whole communities. Incarceration instead of help, barriers to getting our lives back together rather than support for wellness. The inability to secure safe housing and viable employment post release as a direct result of laws that made it nearly impossible for felons to take care of their basic human needs. The second factor was the violence in our communities and a desire to change what was happening. The 1980s and 1990s were a period in which we did see an increase of killings in our communities related to gang violence. People selling crack on street corners and turf wars. One encouraging note on this is that horrible trend peaked in the period between 1986 and 1996 with black on black homicides being cut in half since that era. My sense is that the third factor in what brought our African American recovery communities together is that there are more of us in recovery. Despite all the barriers, a lot of African Americans in America have found their way into long term recovery. We all saw what was happening and had a desire to do something about what we saw. We wanted to pay it forward.

- What has been accomplished through these efforts that has had the most benefit?

We have accomplished so very much. There are grassroots, community based African American run recovery community organizations all across the United States. These organizations are visible and viable evidence of recovery in our communities and the impact that recovery can have to restore our lives, reunite families, and heal communities. There are more 12 step and other recovery fellowship meetings and supports available in our communities than ever. We organize more rallies and public events that raise awareness about the power of recovery than at any point in history. We have policy people and researchers like Dr. Carl Hart, a researcher from Columbia University working on harm reduction and Dr. William Cloud who have worked to dispel myths about addiction and explore recovery capital in our communities.

The expansion of recovery community and the resultant development of recovery capital in those communities are one of the greatest untold stories of the what has happened in the era of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement. Projects like the Detroit Recovery Project, the Northern Ohio Recovery Association and the Association of People Affected by Addiction in Dallas Texas are examples of what can be accomplished. We now have evidence of what happens when recovery communities are organized and provided opportunities and infrastructure to address their own needs in their own communities. We are seeing groups come together and work to address housing, employment and recovery support needs in these communities that have served to heal individuals, families, and whole neighborhoods. They have helped to move us towards a continuum of services and supports that more fully address our needs. Developed by these communities, supported by these communities and for these communities.

- In hindsight, what was missed in efforts to forward these efforts?

We may have underestimated the impact of the unraveling of our SUD service system over this same period we were bringing our communities together. As an example, in 1986 and in the immediately following years, managed care was on the increase in the private insurance market in America. It was hoped that cost management would save money and improve efficiency in medical care. One of the things that happened is that there were mass closures of inpatient SUD and residential SUD programing across the United States. Access to treatment was reduced and lengths of stays shortened. This occurred across all of America and it also in care for African American communities. Long term treatment, that supported wellness across multiple life areas all but disappeared, leaving largely acute care programs that did not meet our needs even as we were coming together to support longer term care and support services.

Dr. Silkworth talked about in the famous Doctors Opinion letter how alcoholics were sick body mind and spirit and that given opportunities to heal, have can be transformative. Longer term services incorporated into a continuum of care that provides support and healing across multiple life areas vital are elements of healing from addiction. Acute stabilization is simply not enough. The gradual elimination of care that met our needs resulted in a growing awareness that we needed to come together and start advocating for ourselves. These are some of things created the environment together and began to shift the tide. We have come along way, we have still farther to go. We need to revitalize a full continuum of care that include harm reduction efforts, long term treatment options and community-based recovery support services.

- Values that helped with the work to unite the community and forward these goals?

I think that some of our African Cultural norms have had a significant positive impact on the efforts within our communities and to support recovery in our communities. One of the pillars of these values is collectivism. It has been expressed as the concept of “Ubuntu” – I am because we are. Who we are as people is shaped by our elders and our relationships with our whole community. We are all connected. That our common bonds within a group are more important than any individual arguments and divisions within it. It fits well with the core values of the new recovery advocacy movement.

The second value relates to our extended family orientation. We have a value of interdependence and communal support. It is a huge strength to tap into for improving wellness and support within our communities. Thinking of a personal example. In the family I am thinking about addiction was prevalent, the father died in 1986. One of the sons went into treatment in 1987. When it came time for family sessions, and the son reached out to connect, at first efforts were not successful. Harms had occurred to the family and there was some estrangement due to his use and the impact his addiction had on the family. When the lens was shifted and the counselor working with him reached out to recruit the extended family members and to focusing on the extended family and their collective wellness, the response was very different. Food was included as sharing of meals is an essential ritual when family comes together. Everyone showed up and rallied together. 39 members of the family, aunts, uncles, nieces, and nephews came together to support not just him, but each other. It was a beautiful thing. This individual was the first member of that family to get into recovery, but now that entire extended family is in recovery. This really highlights the need to focus on extended family work to support recovery in African American communities.

- What message would you want to pass on to the next generation about what has been learned and what remains to be done?

A quote from Carter G. Woodson come to mind. “When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions.” It is vital that we study and understand our own recovery history. It is a rich history. It can inform us of effective ways to harness our resources to strengthen our communities and it can inform us about potential pitfalls and barriers. If you are new to this work or a young person wanting to get involved and support effective change, start with becoming a student of our history and what has been accomplished and how it was done. This is so very important.

The other thing we need to do is focus on mentoring. Wherever you are, establish mentoring processes in which older generations mentor younger generations. These need to be set up as permanent structures within our treatment and recovery support infrastructure. Thinking back to what I was saying in respect to the values and strengths of our extended family focus and the critical importance of supporting each other. What I am thinking of is similar to that. Multigenerational mentoring circles where we invest in the development and the support of our younger leaders. They are our future; it is through them that we will accomplish even greater things. Start these processes now and our younger leaders will see their work extend into the next generation beyond them and into the future.

The 2021 Year-in-Review Community Townhall was an informative talk to thank the community for their contributions to making 2021 such a success, and for sharing in SMART’s excitement for another great year ahead. Please enjoy the presentation.

Watch the presentation on our YouTube channel.

Click here to view the presentation slides.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Stay Strong in Your Recovery During the Holidays

The holiday season presents particular challenges to those suffering from substance use disorder. While it would be ideal for the holidays to be a time of unfettered enjoyment, relaxation, and downtime from the work and stresses of life, it is not always so. For many people, the holidays may also represent a great deal of stress. Not only is now the time for travel and shopping for friends and family, but holiday times can be a reminder of family wounds, fresh or old – especially if there remains any kind of dysfunction in the immediate or extended family.

Those who have never suffered from addiction or mental illness can often overcome these stresses, or suppress their emotions for the sake of peace and quiet. But for those suffering from addiction, and especially those with co-occurring mental illness, may find that the holiday times actually act as a trigger for their disease. Times of high stress can set the stage for potential relapse, as well as depression, anxiety and self-defeating behaviors.

It is for that reason that recovering addicts and those suffering from mental illness should surround themselves with positive forces in their support system. The friends, family members and sponsors that are attuned to their particular circumstances, can be the ones best suited to assist an individual through a potentially difficult time.

This time of year may also be an ideal moment to refresh the relapse prevention techniques learned in recovery and even attend an unscheduled therapy session or two to reinforce the principles of long-term recovery and sobriety. An individual can also use this time to reach out to their treatment center, confirming that their sobriety is on track and revisiting an environment that they know is both welcoming and supportive.

While families and friends may see the holiday time as a reminder of the difficulties and pain they experienced during the time that their loved one was abusing substances, it can also be a time of healing and letting bygones be bygones. Everyone can benefit from happy and healthy holidays without anger or judgment.

Tips to remember:

- Make the time for meetings.

- Keep in touch with your sponsor and friends in the program.

- Try to keep your routine to give each day structure.

- Remember, it is OK to say no if something does not serve or support your recovery.

Additional Resources:

Investing time to prepare for self–care allows you to think of the holiday season in a different way and marks the start of a new tradition in your life of recovery. Don’t succumb to feelings of stress, or even isolation. Here are some additional resources for those in recovery this holiday season:

- For AA meetings near you, by state: https://www.aa.org/pages/en_US/find-aa-resources

- For NA meetings near you, by state: https://www.na.org/meetingsearch/

- Sober podcasts for long drives or to combat feelings of boredom: https://sobercast.com/Home

- NA Speakers on Youtube https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=na+speakers

- AA Speakers on Youtube https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=aa+speaker

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

When a person goes to prison, they are given derogatory labels, considered dysfunctional, and somehow seen as “less than” others in society. Often, they are ignored by the outside world and basically put out of mind. And even though the vast majority of these individuals return to society, little is done to prepare them for the challenges they will face. If they are struggling with a substance-use disorder, this lack of preparation can contribute to negative behaviors continuing.

For SMART Regional Coordinator Chuck Novak, the use of labels is counterproductive (consistent with SMART’s strong stance), and the lack of attention and preparation just doesn’t make sense. Besides facilitating meetings for SMART, he works at Reentry Resource Counseling in New Hampshire, using SMART Recovery tools and principles to counsel those he calls “returning citizens” (rather than ex-offender or similar label).

Novak himself was once a returning citizen, having served five years for behavior that stemmed in part from his own addiction and negative choices. When he was released, he was certain of one thing.

“I knew I needed to do a different job; I knew selling drugs was going to be out…I wanted a new life.“

He started college and chose to pursue a path where he could help others, specifically those who had been incarcerated. While he himself was behind bars he heard about SMART in passing, it was mentioned in a book about Rational Recovery and Albert Ellis, the founder of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

It made enough of an impression to choose to do a research paper for a college class. He titled his paper “Get SMART” and it turns out he was the one who has ended up getting professionally and personally gotten by SMART since then. Now he incorporates CBT and many other tools in his work with individuals who are reentering society. He has a passion for making sure SMART is well known, and a unique name for his strategy.

“I implemented something I called operation bed bug, [deciding that] everybody who came into the detox where I was working in Manchester New Hampshire was going to get “infested” with SMART Recovery, so in the detox program they were going to learn [SMART tools like] the hierarchy of value, cost-benefit analysis, disputing irrational beliefs, and then they were going to go off into other rehabs and they were going to tell the counselors about SMART”

Besides his colorfully named initiative, Novak credits other powerful resources, such as SMART’s InsideOut: A SMART Recovery Correctional Program®. He notes that InsideOut contextualizes “criminal thinking errors” which are an extension of irrational thinking. This aligns with the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ perspective, making his work in drug courts well received.

“At Reentry Resource Counseling we coordinate and offer services for the Federal drug court of New Hampshire. So, I do individual counseling, and I do another cognitive behavioral group specifically for the drug court.“

Novak also notes the value of SMART’s Successful Life Skills because it covers things like budgeting, anger management and other practical matters–not just stopping substance misuse. As a probation officer put it to him, it’s great that they aren’t doing drugs, but they now have to learn how to do life.

Currently, Novak makes presentations about SMART as often as he can, stressing that success comes from keeping your goals and values in the forefront of your mind. In this way, Novak says, participants can not only discover life beyond addiction, they can fully engage in it. Just like he has done for 20 years and counting.

Help Us Reach More Returning Citizens in Need

As demonstrated in Chuck’s story, the ripple effect of impacting one life impacts others. It is because of individuals like Chuck, who experience SMART and then decide to use their time, energy, and resources to spread its self-empowering messages, that we are able to reach more and more people who need support.

Unfortunately, there are communities – and returning citizens– across the country who still desperately need increased access to free, self-empowering, science-based mutual help groups. We are working to meet that need.

Your year-end gift to our Growth Fund will be put to work immediately, to help more people like Chuck and the participants in his meetings find the self-empowering recovery tools and peer support they need to overcome addiction and go on to live fulfilling and meaningful lives.

Additional Resources:

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Guest blog by Tom Horvath, Ph.D.

The harm reduction approach to addressing addictive problems has until recently been highly controversial, at least in the U.S. Treatment and other change efforts in the U.S. have been primarily guided by the views that addiction is a disease and that the 12-steps are the primary (or only) method for change. Harm reduction accepts and encourages small steps toward change. The U.S. approach has typically required an immediate and large change, often involving a completely new perspective: “I’m an addict, I have a disease, I will abstain from everything forever.” The small steps approach of harm reduction, even though it describes how most human change occurs, has often been considered unacceptable and dangerous.

However, opiate overdose deaths have skyrocketed in recent years. It has been increasingly clear that the U.S. approach to supporting change is far too ineffective. Alternatively, the most effective approach to treating opiate use disorders involves using medications that parallel, to a significant degree, the effects of opiates. From an abstinence-only perspective these medications are unacceptable. But the number of deaths has been even more unacceptable to the public and governments at all levels. Traditional U.S. treatment is increasingly being over-ruled. For the first time, a U.S. president’s drug policy specifically mentions harm reduction as a primary principle.

Harm reduction involves a wide range of efforts and approaches. They support “any positive change.” Unlike the traditional prediction (that such changes provide a false hope of “real change”), harm reduction typically results in changes that are stable. Harm reduction is much more likely to place someone on a positive path and keep them there. When there is insistence that major change must happen immediately, the drop-out rates (or unwillingness to attend treatment at all) are substantial.

Undoing Drugs describes harmful ideas and methods that need to be “undone” in order for the U.S. to move forward with a harm reduction approach. In particular we need to update our understanding of “drugs.” In discussing one of the academic pioneers of harm reduction she writes:

[Alan] Marlatt knew that “undoing drugs” was essential to the mission: if alcohol isn’t seen as the drug that it is, its many users can easily dismiss “druggies” as some alien group whose experience is completely unlike their own. The spectrum of substance use must be seen in its entirety, so that we can recognize that it is indeed universal, across cultures and time (pg. 192).

As Szalavitz carefully documents, harm reduction got a substantial boost in the mid 1980s with the recognition that HIV and needle sharing went together. If an HIV user shares a needle with another drug user who also injects, the chances of transferring the infection are substantial. Of course, if we could persuade all drug users to stop using drugs, there would be no need for needle sharing. Also, of course, in any one moment we have not thus far been sufficiently successful with that kind of persuasive effort, and probably never will be.

Early harm reduction advocates focused on teaching drug users how to disinfect their needles, or better, provided them with clean needles, or even better, provided users clean needles and a safe place to inject (where medical staff were available in case of overdose). Each of these actions keeps users alive, setting up the possibility for change later. As some have said “dead addicts can’t recover.” The traditional treatment community, and many citizens and legislators, initially rejected this approach, preferring that drug users “hit bottom” even if it meant many of them died. The controversy was fierce, until the rise in opiate overdose deaths compelled us to seek new solutions.

Szalavitz documents the persistence of the individuals and organizations in the U.S. (supported by leaders in other countries) as they made the harm reduction activities available. Many got arrested or denounced. Many were themselves drug users who were able to change (as Szalavitz did, in the personal story she relates in the book). She states, “since I’d been spared, I wanted to learn everything I could about HIV prevention for IV drug users (pg. 31).” Many others were not so fortunate and died from overdose or HIV. For supporters of harm reduction this book provides the history, and the rationale, you might be only dimly acquainted with: “The history of harm reduction shows us that there is a better way—and it lies in undoing and dismantling all of our mistaken concepts about the nature of drugs and the people who take them (p. 12).”

Szalavitz has been a leading author and journalist about addiction, science, and public policy. She has diligently built her body of work and her career over three decades. In an interview I conducted with her (for the SMART Recovery National Conference, October, 2021; available on the SMART Recovery YouTube channel) she talks about these subjects in such depth and detail that it was clear she could probably dictate another book (it would be her 9th) in just a few days. Nevertheless, she conducted extensive research for this book specifically, including interviewing many of the leaders of the harm reduction movement. The harm reduction movement has been so massive that her book could present only U.S.-centric highlights: “Many additional specialized works need to be written, particularly to encompass the story of harm reduction outside of the United States and within specific communities (pg. xi).” To that end she is creating an archive of interviews and other material, soon to be available at www.maiasz.com.

This book has sections that focus on HIV and how it spurred harm reduction, leaders and activists, cities (e.g., New York, San Francisco), countries (e.g., the UK, the Netherlands), positive actions (like needle disinfection), legal issues and court cases, harm reduction definitions, public policy debates, racism (which is a major theme), overdose prevention, pain management, how to include drug users in decisions about them, housing for drug users, the problems with traditional treatment and “tough love,” the scientific evidence that supports harm reduction (that evidence is substantial), and where we need to go from here (in brief, to emulate Portugal, which has 20 years of substantial success with drug use decriminalization). Her focus on creating a sensible, equitable, and realistic future is crucial, because it would appear that we are not even halfway “there.”

If you have had any doubts about the value of harm reduction, this book is for you.

Other books by Maia Szalvaitz

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

In the most recent 10 years especially, I’ve been noticing some activity in our field concerning advancement of public health measures (e.g. cigarettes) and harm reduction strategies (e.g. opioids). Some of these efforts seem to include the notion that widespread harms would be reduced, and widespread health would be advanced, if use of drugs was:

- Culturally accepted

- Low cost

- Widely available

- Natural, not a tainted supply

- Low or lower potency

Backing up a bit, I’ll say this. I grew up in Southeast Asia and moved to the USA in the late 1970’s, just before my teenage years. I experienced culture shock upon moving to the USA, and have many, many stories about it that remain quite clear to me. Some of those stories pertain to drugs and drug use, but most of them pertain to the basics of everyday life.

In SE Asia, I saw the use of betel nut all the time. After moving to the USA, I never saw betel nut or the use of betel nut, ever again.

Effects of the use of betel nut (as quoted below) include: addiction, various cancers, neuronal injury, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmia, hepatotoxicity, asthma, obesity, type II diabetes, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, hypothyroidism, prostate hyperplasia, infertility, suppression of T-cell activity, and harmful fetal effects if used during pregnancy.

In Southeast Asia, betel nut has traditionally been low-cost, culturally accepted, widely available, natural and not from a tainted supply, and of low potency. And despite those factors, betel nut has long been a public health nightmare.

I often think of betel nut while I listen to arguments in favor of heroin that could be:

- low-cost

- widely available

- pharmaceutically pure

- culturally accepted, and

- not tainted with high potency but pure opioid additives like fentanyl.

I encourage the reader to read on through some recent findings below, and a question at the end.

Some Recent Findings

Garg, A., Chaturvedi, P. & Gupta, P. C. (2014). A Review of the Systemic Adverse Effects of Areca Nut or Betel Nut. Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. 35(1):3-9.

Areca nut is widely consumed by all ages groups in many parts of the world, especially south-east Asia.

There is substantial evidence for carcinogenicity of areca nut in cancers of the mouth and esophagus. Areca nut affects almost all organs of the human body, including the brain, heart, lungs, gastrointestinal tract and reproductive organs. It causes or aggravates pre-existing conditions such as neuronal injury, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, hepatotoxicity, asthma, central obesity, type II diabetes, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, etc. Areca nut affects the endocrine system, leading to hypothyroidism, prostate hyperplasia and infertility. It affects the immune system leading to suppression of T-cell activity and decreased release of cytokines. It has harmful effects on the fetus when used during pregnancy.

Little, M. A. & Papke, R. L. (2015). Betel, the Orphan Addiction. Journal of Addiction Research and Therapy. 6:e130. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000e130.

…there is virtually no public awareness or concern in Western nations about the fourth most widely used addictive substance, commonly known as “betel nut”, even though 300 to 600 million people worldwide are potentially addicted and at increased risk for oral disease and cancer. Of course, for much of the Western world, the ignorance and indifference to this widespread addiction can be attributed to what Douglas Adams identified in his Hitchhiker novels as the closest thing to invisibility, the SEP (somebody else’s problem) field. For thousands of years the use of areca nut (betel) has been endemic throughout South Asia and the Pacific Islands.

The main psychoactive ingredient of the areca nut is arecoline, which is known to be a muscarinic cholinergic agonist. Since arecoline is a weak base, another important ingredient in the betel quid that is required to alkalinize the saliva and permit absorption is some form of slaked lime, often from burnt sea shells or coral.

Historically, betel use cut through all levels of Asian society and was very common amongst the nobility.

The global health burden associated with areca use worldwide necessitates attention towards this addictive behavior. Given that it has been demonstrated that users do indeed become dependent, and that a substantial portion of the areca users have the desire to quit, it seems to be an addressable problem.

Papke, R. L., Hatsukami, D. K. & Herzog, T. A. (2020). Betel Quid, Health, and Addiction. Substance Use and Misuse. 55(9): 1528–1532. doi:10.1080/10826084.2019.1666147.

Areca addiction. Betel quid use (areca with or without tobacco) is an orphan addiction (Little and Papke, 2015), little studied and poorly understood. But there is an ever-growing appreciation for the global health impact of this form of drug addiction (Mehrtash et al., 2017; Niaz, et al., 2017). The majority of the betel quid users are stuck in a cycle of use and dependence while aware that they put their health at risk

Tungare, S. & Myers, A. L. (2021). Retail Availability and Characteristics of Addictive Areca Nut Products in a US Metropolis. Journal Of Psychoactive Drugs. 53(3):256-271. doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1860272.

In this field observational study, we found that areca products were relatively inexpensive, readily available, and easily purchased in grocery stores visited in Houston, TX.

Sumithrarachchi, S. R., Jayasinghe, R. & Warnakulasuriya, S. (2021). Betel Quid Addiction: A Review of Its Addiction Mechanisms and Pharmacological Management as an Emerging Modality for Habit Cessation. Substance Use and Misuse. 56(13):2017-2025.

Even though literature reveals a few cessation programs through behavioral support for (betel quid) addiction, its success has been limited in certain instances mainly due to addictive properties of (areca nut), resulting in withdrawal and relapse.

Consider the research side of the question.

I wonder if there would be interest in conducting a naturalistic study, with as many subjects as the size of a whole population, and carried out prospectively over thousands of years – to see if culturally accepted drug use, at low cost, with wide availability, natural and not from a tainted supply, and of low or lower potency, is sufficient?

Before we finalize our public health policy and harm reduction measures, we can study betel nut for lessons.

One of the reasons that I am so focused on our history as a recovery movement is that our past can tell us a great deal about the types of challenges we have faced, which strategies have been most successful, and the themes that occurred over time that influenced these processes. It helps us see our path forward.

The short version of our history is that everything in our entire SUD care system originated with the recovery community. Yet, those same systems then move away from the needs of the recovery community over time. We shift towards polices to punish people out of addiction. We put up care access barriers and expand administrative burdens as a direct result of our societies deep biases against persons who experience substance use disorders. Our best recovery community efforts then whither on the vine. A decade or two later, the recovery community rises again and rebuilds for the next cycle. Far too much energy gets lost as we are forced to reinvent the wheel each time.

As I spoke about recently in this piece, PAINFULLY OBVIOUS, there is deep discriminatory processes baked into our institutions. Partially by design. One of our authentic recovery community organizations (RCOs) compared what is being done with our current competitive grant process is that of a piece of meat being thrown into a pack of starving dogs and then watching them fight and hurt each other for basic sustenance. You can’t take grassroots community organizations who have never had stable funding and expect them to fight each other (and longer established treatment and other human service organizations) for a few dollars and expect to end up with a cohesive and inclusive care system.

One of the focuses of the new advocacy recovery movement was to nurture RCOs across America, in every community. It is a worthy vision. It starts with acknowledging that RCOs, run for and by people in recovery focused on supporting their own communities is valuable enough a resource to develop in its own right. Local organizations to support recovery in their communities and statewide recovery community organizations to provide technical assistance, training, and support. We are not there yet, not even close. This is in large part because we have set up a Conflict Model that pits communities who want to build community against each other to fight for table scraps of funding.

We are at a critical moment in history. Substance misuse is dramatically increasing in our society, in part as a result of the pandemic and a lot of underlying social strife and turmoil. Drug use is clearly shifting to multiple substance use patterns that make single substance treatment strategies less impactful for persons with severe substance use disorders. Our public SUD care system, underfunded and overburdened with demands and a decades long workforce crisis is crumbling even as we see more challenging times ahead. What we are doing is not working.

We are at that all hands-on deck; it takes the whole village moment. Our family members and neighbors are dying. It is a horrific process it is costing us vast treasures in lost lives and broken communities. Addiction and the consequences of it is the primary driver of human service and correctional costs in America. Yet, we pit our new, fledgling grassroots recovery community organizations against our established system of care and each other to sustain conflict. It is the antithesis of what is needed at this moment in time. We need the recovery set aside – a ten percent federal block grant for recovery, and then at the state levels, we must ensure such resources are allocated in ways that support the development of authentic RCOs instead of setting them up for conflict with each other and the rest of our care system.

We are in the early phases of a syndemic, with the addiction epidemic and the pandemic coming together in ways that will create a decade with even more challenge than we faced in the last decade. It is time to:

- Dedicate resources to developing Recovery Capital inside of our states and at the local and regional levels. Not in a competitive dog eat dog model, but one that honors and supports authentic recovery communities. Not divide and conquer nontransparent funding processes, but inclusive and recovery community oriented.

- Ensue that the recovery community is meaningfully engaged in how funding is allocated and what it builds – systems that embrace a recovery model, which understands and acknowledges that communities in recovery are the experts in what they need and how to build effective care models focused from the ground up, not from the top down.

- Use our SUD resources inside of our states instead of bringing in vendors from outside of the state to provide some training or technical assistance. We need to build recovery service and recovery community technical assistance capacity nested within recovery community organizations in every state, not send our monies elsewhere.

- We need to invest in long term recovery focused on the five-year recovery paradigm. We know that addiction is a long-term condition, yet all our models and research is all focused on narrow, short-term goals. It needs to change. We need to think bigger and build a care system that supports long term recovery.

- We need to take a hard look at discriminatory practices that set up barriers for persons in recovery from getting into and staying in our workforce. It is discrimination. Persons in recovery have always been the backbone of our SUD workforce. We need to create on ramps for persons in recovery to get into our field and then grow them.

We face a collapsing workforce and burgeoning needs on one hand and long term, recovery-oriented community building opportunities we are not using to even a fraction of their potential on the other. We know we will see a dramatic need for behavioral health needs created by the pandemic and social strife. We need to reinvent our systems to focus on strengthening grassroots community resources and expand recovery capacity across all of our communities, in partnership with those communities. We need to move beyond our low expectations for persons in recovery caused by discriminatory views about us and towards a long term recovery model.

What is true is that we know that 85% of persons with an SUD who reach five years of recovery stay in recovery for the rest of their lives – let’s build a system that focuses on these needs together. It has never been needed more than it is needed right now. Let’s move forward inclusively instead of starving our recovery community organizations of resources as we watch our friends and family members die. To sustain such a conflict-oriented model at this point must be called what it is, which is overt discrimination.

It is time for change, lives depend on it. We need to actually embrace recovery community organizations for what they are, one of the best options we have on the table to develop and support.

It takes a (recovery) village.

In a recent conversation, a colleague in the field told me they are attempting to “Catalog the biases at work among many of the scientific and medical experts in the field.” And they said to me, “I’d like to hear what biases you observe.”

This blog post serves as my attempt to respond to that request. What biases do you observe?

My current list of those biases is as follows:

- The idea that knowing the list of diagnostic criteria is the same as understanding the disorder

- Ignoring signs and symptoms of the illness that come from non-research sources

- Transforming each of the diagnostic criteria into a simple yes/no question

- Not including psychological struggles or improvements when determining remission

- Forgetting the complexity of real-world clinical implementation

- Conducting research with simple and compliant subjects, then doing clinical reasoning based on results of that work

- Understanding the illness by emphasizing the clinical discipline they were trained in

- Working to suppress symptoms and then conflating that with sufficient improvement

I’ll say more about each one of those in order, below.

Biases At Work

- In my experience, scientific experts in the field tend to use the criteria that are meant to be used to diagnose the presence of a substance use disorder as their main way of understanding the illness.

One trend inside the doing of that error is setting aside the phenomenological characteristics of addiction illness that are not found in the diagnostic criteria.

But people with addiction illness, those in recovery, and their family members – if they read over that diagnostic criteria list – would know that the simple list of diagnostic criteria falls far short of a sufficient quantitative and qualitative description of any one person’s addiction illness. Further, people who are maintaining recovery know all too well the signs and symptoms of their illness that are not found on the list of diagnostic criteria, and that tend to re-emerge at times over the years.

There are a variety of documented sources of that kind of information. My two favorite sources are older ones:

- The “Jellinek Chart” shows common signs of alcoholic disease progression.

- Gorski lists relapse warning signs that show up before going to back to using (during the early, middle, and later stages of regression out of recovery).

Both of those sources describe what it is like to have or to witness the illness. Lists like these can help someone understand addiction illness in its various forms and stages.

Here’s my favorite example of limiting one’s understanding of an illness to the list of its diagnostic signs and symptoms or objective research targets:

- Someone I know was present when a neurological bench scientist working in Parkinson’s research met a person with Parkinson’s for the first time. They were delighted to meet each other. But when the scientist explained what they were working on (movement problems, naturally) the person with Parkinson’s asked if they ever worked on gut motility. The person with Parkinson’s had to explain to the researcher that there are whole sets of problems not visible to others. The bench scientist was very grateful to hear of a whole new array of research targets – from a person who knew in a whole different way.

2. The bias listed as #1 above leads naturally into this next one. In my experience, empirical scientists/researchers are largely unaware of, or are quick to ignore or dismiss, objective signs that are universally accepted by clinicians and the people that experience the illness.

- But meanwhile, clinicians are expected by research scientists and medical experts to work with and not set aside the objective signs that are identified by researchers.

3. When they use the list of diagnostic criteria, they tend to turn each of the diagnostic criteria into a simple and straightforward question and ask the person if they ever experienced that or not. They generally do not first immerse themselves in the case history, then obtain information from data sources other than the person’s self-report, and last of all make a judgement from all the information gathered as compared to the diagnostic criteria.

4. In my experience they view the illness as being in remission if use of the substance stops or if the countable number of diagnostic criteria that are currently present shrinks to a small enough number.

- But quitting is diagnostic, not prognostic. And a simple elimination or reversal of the facts or information needed to identify the illness is not the same as the person healing or the same as full recovery. Or that the illness is not still in operation in other ways not listed in the diagnostic criteria.

5. In my experience research scientists or medical experts far from clinical work tend to make flawed assumptions (based on the logic of their training) about clinical implementation. For example, clinicians know we provide treatment based on practice guidelines. And clinicians tend to ask about adjusting the use of a guideline based on the facts or circumstances of the individual patient. And in my experience, most academics or researchers would answer such a question by saying something like, “Take a closer look at the guideline”. They believe most of the important individual differences from one patient to another are covered in the practice guideline for that disorder.

- But working clinicians know that patients have multiple disorders or divergent needs. And therapists might need to commonly use multiple practice guidelines simultaneously or have to attempt to blend them.

At that point, if that was explained to the research scientist or medical expert, their response would be to say something like, “Oh”, and the topic of the real world would be discussed.

6. Survivorship bias. Studies evaluate those that enter a study. They do not study those who can’t or won’t enter the study. And they study those that complete the study, not those that can’t or won’t complete the study. And studies only let in those who are healthy enough and uncomplicated enough to be studied in the first place (such as having only one disorder, and having no cognitive impairment, etc.).

- Should we only study the survivors of our protocol? Shouldn’t we also study the drop-outs, no-shows, and those that didn’t make it? Clinicians generally see complicated and ambivalent real-world patients in real-world clinical and community settings.

7. In my experience, their understanding comes right from their individual clinical discipline. They limit themselves to looking for things their specific tools are geared to find and tend to have little recognition of this as a self-limiting process.

- For example, physicians generally see addiction as a brain illness with bio-psycho-social manifestations. They do not tend to see addiction as a bio-psycho-social-spiritual illness.

In my experience this error becomes more rare or smaller when they are working as a member of a team. For example, when such a person is one member of a team (composed of staff from clinical psychology, primary health, nursing, spiritual care, addiction counseling, marital and family therapy, wellness/recreation therapy, and psychiatry) their information is added to that from the other disciplines, is contextualized, and in that way their understanding improves.

8. In my experience, they view improvement in a person as nothing more or less than suppressing symptoms (reducing the number or intensity of problem indicators). Working to suppress symptoms is the focus.

- They work toward obtaining statistically significant differences and lose focus on clinically significant differences.

- Working toward health and wellbeing is forgotten. That is to say, the focus is on the course of illness, not the course of recovery.

I’ll close with a quote to consider from Thomas Payte, MD:

The majority of the population prefer the certainty of illogical conviction to the uncertainty of logical doubt.

It seems to me this applies to all of us as people, including we professionals, and not to our patients only.

Recommended Reading

Haun, N., Hooper-Lane, C. & Safdar, N. (2016). Healthcare Personnel Attire and Devices as Fomites: A Systematic Review. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 37:1367–1373.

Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2005). Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. PLOS Medicine. 2(8): e124. 696-701. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

James L. (2016). Carl Jung and Alcoholics Anonymous: is a Theistic Psychopathology Feasible? Acta Psychopathol. 2:1.

Petrilli, C.M., Saint, S., Jennings, J.J., Caruso, A., Kuhn, L., Snyder, A., & 2 Vineet Chopra, V. (2018). Understanding Patient Preference for Physician Attire: A cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2017-021239.

Twerski, A. (1997). Addictive Thinking: Understanding Self-Deception. Hazelden.

Weiss, D., Tilin, F. & Morgan, M. (2018). The Interprofessional Health Care Team: Leadership and Development, Second Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA.