This post will consist of an overview of one particular research report, and some of my thoughts about it. Here is the citation of the paper I’ll be discussing:

Yovell, Y., Bar, G., Mashiah, M., Baruch, Y., Briskman, I., Asherov, J., Lotan, A., Rigbi, A. & Panksepp, J. (2016). Ultra-Low-Dose Buprenorphine as a Time-Limited Treatment for Severe Suicidal Ideation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 173:5.

Numerous things in this article concern me. I’ve been meditating on it since around 2017. At this point I’ve decided to share the citation for the paper, quotations from the article that draw my particular attention, and some of my thoughts about those quotations.

Here’s the study objective from the top of the first page.

Objective: Suicidal ideation and behavior currently have no quick-acting pharmacological treatments that are suitable for independent outpatient use. Suicidality is linked to mental pain, which is modulated by the separation distress system through endogenous opioids. The authors tested the efficacy and safety of very low dosages of sublingual buprenorphine as a time-limited treatment for severe suicidal ideation.

Here’s the study population

The study was performed on “Severely suicidal patients without substance abuse…”

Here’s the study intervention

The study examined “…ultra-low-dose buprenorphine (initial dosage, 0.1 mg once or twice daily)…”

The results

Participants in the experimental group receiving buprenorphine “…had a greater reduction in Beck Suicide Ideation Scale scores than patients who received placebo (N=22), both after 2 weeks (mean difference 24.3, 95% CI=28.5, 20.2) and after 4 weeks (mean difference=27.1, 95% CI=212.0, 22.3).”

Statements about history, rationale, and safety

Opioids were widely used to treat depression from about 1850 to 1956. Because of their addictive potential and lethality in overdose, opioids were replaced by standard antidepressants once these became available. However, several studies since then have found them to be effective for treating depression.

Read those sentences again. I find that passage particularly odd.

Opioids are involved in more deaths than any other drug class in fatal pharmaceutical overdoses in the United States. Thus, the lower lethality of buprenorphine and the very low dosages employed in this study were crucial for enabling its independent, home-based use. However, buprenorphine is potentially addictive and possibly lethal. We therefore designed this study as a time-limited trial for severely suicidal patients without substance abuse.

Exclusion criteria were a lifetime history of opioid abuse…substance or alcohol abuse within the past 2 years, and benzodiazepine dependence within the past 2 years.

Adherence to the protocol

“Outpatients received the study medication for the following week during their weekly visits, and took it independently at home. Average adherence, measured by pill counts, was 92%.”

- I wonder if the medication was not taken.

- And I wonder what happened with the unused opioids.

Comorbidities

“More than half (56.8%) met criteria for borderline personality disorder…”

- What characterological or environmental context must be present for this buprenorphine protocol to be declared unsafe in a community setting?

Clinical history vs. follow-up

“All participants denied withdrawal symptoms during their follow-up appointment 1 week later. It is possible that in this opioid-naive population, the short duration and low dosages protected against dependence.”

The bottom line

“In this study, the time-limited use of very low dosages of buprenorphine was associated with a decrease in severe suicidal ideation.”

- Beyond a measurable decrease, I am curious what kind and level of suicidal ideation is clinically relevant regardless of a measurable decrease.

Required disclosure

“Dr. Yovell reports being listed as an inventor on a patent application for the use of low-dose buprenorphine for suicidality; he has assigned his rights in the patent to the University of Haifa but will share a percentage of any royalties that may be received by the university.”

- Why not simply remove this person from the research project due to conflict of interest or the potential appearance of a conflict of interest?

The following points have also occurred to me over my years of considering this study:

- The authors discuss neural processing leading to psychic pain as the medication target. The thinking and behavior they are attempting to change are merely downstream from the medication target. Thus, acetaminophen could also have been tried at 3 doses beyond the inclusion of a placebo group – it dampens the neural processing that produces psychic pain, just as it does with physical pain.

- We know opioids blunt awareness of pain, and do not diminish the neural activity that produces pain (as acetaminophen does, while leaving the mind clear). I wonder what an imaging study would show?

- Linking of opioids, mental pain, and suicidality seems to indicate that pain management is the goal. Should we reify psychic pain as another vital sign? What were the unintended consequences of establishing physical pain as the fifth vital sign?

- Thousands of years of human history were enough to already show us that opioids decrease the experience and report of pain. Were we in doubt of this?

- We already know that some people find that taking some drugs makes them feel less bad, temporarily. Were we in doubt of this?

- You cannot prove the null hypothesis (prove a negative). Concerning their selection criteria, rather than say “without substance abuse” they could have said, “Presenting no evidence of a current and active SUD”.

- Was this a first exposure to prescription opioids for some in the study? If so, might it flip the genetic switch for atypical responders (not just atypical metabolizers)? Was that possibility screened for? How long should atypical responders in such a study be followed after the study is concluded?

- Is “ultra-low-dose” a standard and recognized term, or used here as a descriptive label for other purposes? They could simply name the compound and dose.

- Is the reduction in the Beck score clinically significant or an arbitrary metric – one that is reliable, valid, and irrelevant (Hart & Jaccard, 2006)?

- Generally speaking, any score that is initially extreme will, over time, tend to regress to the mean. That is, extreme scores don’t last long and tend to become less extreme over time. So, did they obtain a treatment result, or was this treatment superimposed over an already improving picture?

- How would we know if the change they report is clinically significant?

- Did the suicide rate in the treatment group and the placebo group differ after the study?

- What is the base rate of suicide among individuals matched to those in this study (with no treatment and on the same array of psychotropic medicines)? If we don’t know the base rate, to what do we compare the results of this study – just their scores at the beginning of the study?

- How was it decided to place opioids among a suicidally depressed patient group located in the community (outside an institutional setting) during an opioid epidemic?

- The researchers screened against “lifetime history of opioid abuse” and excluded participants accordingly. But non-problematic use of opioids (aka successful use) was not mentioned as an exclusion criterion.

- “Exclusion criteria were a lifetime history of opioid abuse…substance or alcohol abuse within the past 2 years, and benzodiazepine dependence within the past 2 years.” But addiction illness is one illness, even if multiple substance classes are involved.

- I wonder how many of the study participants had 2 or more of the Big 5 SUD criteria (desire or efforts to control, craving, diminished role function, loss of activities, and withdrawal) as part of their “abuse” diagnosis at the time that diagnosis was active? That is to say, I wonder if some of the participants with no “substance abuse” within the past 2 years were actually in the course of illness for developing SUD moderate-to-severe at the time their problematic substance use was active. And if so, could the presence of Big 5 SUD criteria be considered as possible exclusion criteria for participation in such a study?

- The authors declare their participants were opioid naïve. But lack of a clinical diagnosis of a use disorder is not the same as naïve to use of the drug.

In conclusion I’ll say that this paper was one of the research reports that developed my focus some years ago on what I simply call “Harms of Use”. That focus led to me gather such papers (and related papers) over a series of a few years, read and study them, and prepare materials for education, training, etc. based on their content.

References

Hart, B. & Jaccard, J. (2006). Arbitrary Metrics in Psychology. American Psychologist. 61(1): 27-41.

Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2006). Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. PLoS Medicine. 2(8) e: 124. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

Suggested Reading

DeWall, C. N., Chester, D. S. & White, D. S. (2015). Can Acetaminophen Reduce the Pain of Decision-Making? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 56:117–120.

DeWall, C. N., MacDonald, G. M., Webster, G. D., Masten, C. L., Baumeister, R. F., Powell, C., Combs, D., Schurtz, D. R., Stillman, T. F., Tice, D. M. & Eisenberger, N. I. (2010). Acetaminophen Reduces Social Pain: Behavioral and neural evidence. Psychological Science. 21(7):931-937. DOI: 10.1177/0956797610374741

Durso, G. R. O., Luttrell, A. & Way, B. M. (2015). Over-the-Counter Relief From Pains and Pleasures Alike: Acetaminophen blunts evaluation sensitivity to both negative and positive stimuli. Psychological Science. 26(6):750–758. doi:10.1177/0956797615570366.

Maughan, B. C., Hersh, E. V., Shofer, F. S., Wanner, K. J., Archer, E., Carrasco, L. R. & Rhodes, K. V. (2016). Unused Opioid Analgesics and Drug Disposal Following Outpatient Dental Surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 168(1): 328-334.

Randles, D., Heine, S. J. & Santos, N. (2013). The Common Pain of Surrealism and Death: Acetaminophen reduces compensatory affirmation following meaning threats. Psychological Science. 24(6) 966 –973.

Can the presence of recovery, or the level of recovery function, be somehow detectable when it is unspoken and not overtly displayed?

Can recovery be intuitively recognized or somehow felt in another person?

Can recovery be intuitively recognized within an interpersonal space?

Can recovery be present and sensed in the atmosphere?

Sixth-sense, Spidey-sense, Radar

When you walk into a room, do you ever pick up on any unspoken content, themes, trends, or the basic agenda of those in the room?

What is felt? What is perceived? What is apprehended?

In life it seems that sometimes, somehow, we can latch upon and perceive the unspoken content of others. Somehow, in the room we enter, we sometimes register the collective assumptions, world view, goals, or direction of those assembled in the room.

Our human heritage and social epigenetics have seemingly equipped us by developing within us such radar and radar capacity.

With 32 years of service in residential addiction treatment programs now behind me, I think I can say that I have at times experienced the sensing of the dormant agenda in a group of people – when I come into the room.

Likewise, some with long-time recovery can sense the:

1. presence and level of health/vitality of recovery, or

2. presence and depths of the collective mental relapse process,

that is latently present, yet unspoken, in the collective gathered for a meeting.

I’ll go ever further and say that sometimes the basic content in the room (of recovery, or of relapse process) can be sensed – even when those in the room that are holding the agenda are seemingly unaware of their own content.

Objects, Background, and Open Space.

In life, objects influence us.

The physical objects around us, the content we consider in our minds (objects of thinking), and our deep assumptions about life that we do not consciously consider (buried mental objects) exude their influence.

Do these objects and the processes related to them effect the atmosphere around us? (And therefor others around us as well?)

I described the importance of the background within a work of visual art in an essay titled Negative space. What is shown other than the main object represented in the art?

A simple solid color, a blue sky, or a complex crosshatch weave of various colors might serve as a background that the object in the art sits on, or sits in front of. These are examples of visually representing “negative space”.

In that essay I also highlighted both the concrete content and the aesthetic quality of the background – even of a seemingly plain background.

Paradoxically, the content of the negative space in art – while represented concretely – is itself without an overt object.

The Feel of the Negative Space

Does the group room, meeting room, or counseling office have a negative space? Yes. The negative space is the open atmosphere, in the background. What forms its quality?

Suppose someone experiencing active addiction illness has family members living with them. Do those family members experience the second problem of a toxic negative space within the home?

If the object of the drug itself and the object of the process of active using are removed – a toxic negative space might form. Unless, perhaps, recovery fills the void in the person, the family members, the atmosphere, and the negative space within the home.

Where is the invisible man?

Can we sense addiction illness, or relapse process, or recovery, when we enter a room?

Are there objects deposited by addiction? Are there objects deposited by recovery?

Does a mental relapse process unearth objects prior to use resuming?

What objects does recovery raise?

Toward making these discoveries we can explore locations such as:

- What is non-observable (not visible)

- What is non-discursive (not in shared words)

- What is not symbolized or represented by symbols

- The social system

- The unconscious

- Multi-generational structures

What do the family members and the one with addiction illness experience in the atmosphere during:

- active addiction illness

- periods of unwanted abstinence

- recovery?

For the sake of others, I wish our recovery science was sufficient such that we could “throw flour on the invisible man”, locate recovery function, and assess recovery quality.

Suggested Reading

Aristizabal, M. J., Anreiter, I., Halldorsdottir, T., Odgers, C. L., McDade, T. W., Goldenberg, W., Mostafavi, S., Kobor, M. S., Binder, E. B., Sokolowski, M. B. & O’Donnell, K. J. (2020). Biological Embedding of Experience: A Primer on Epigenetics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117(38) 23261-23269. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1820838116

Buber, M. (1923/1937/2010). I and Thou. Martino Publishing.

Cole, S. W. (2009). Social Regulation of Human Gene Expression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 18(3): 132-137.

Hollis, J. (2015). Hauntings: Dispelling the Ghosts Who Run Our Lives. Chiron: Asheville, NC.

Lewis, J. & D’Orso, M. (1999). Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement. Harvest Books.

Mello, C.V., Vicario, D. S. & Clayton, D. F. (1992). Song Presentation Induces Gene Expression in the Songbird Forebrain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 89: 6818-6822.

Roberts, R. (2011). Psychology at the End of the World. The Psychologist. 24(1): 22-25.

Sänger J., Müller, V. & Lindenberger, U. (2012). Intra- and Interbrain Synchronization and Network Properties When Playing Guitar In Duets. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 6:312. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00312

Wall, H. (2011). From Healing to Hell. NewSouth Books.

When discussing the goal of abstinence for opioid use disorder, it sometimes comes up that it’s much safer to stay in medication assisted treatment (most often methadone or buprenorphine) than to detox. I agree, but I would never advise a patient just to detox. Detox is a procedure, not a treatment as such. If all you do is offer detox, or it’s the only part of the package the client will take, then the outcomes are not only bound to be poor, they are also bound to be fraught with danger. Detox is not enough.

We need to exercise caution with such requests – relapse rates are very high after detox. Loss of tolerance to opioids occurs quickly and relapse then leads to risk of overdose and death. There can be a reluctance or even refusal to look at supporting people to move on from MAT. But here are some considerations for clinicians:

- In the UK there are thousands of people in long term recovery from opiate dependence, so clearly some people have managed this safely

- There are people on MAT who want to try to move on

- In some areas of Scotland this option is already well established

In my experience, some (if not many) patients want a stand-alone detox and have unrealistic expectations of the outcome and discount the risks. Detox may be part of a process that leads to healing, but detox itself does not heal. Thinking of detox in isolation from the other factors that promote recovery, and simultaneously reduce risk of relapse, is not a good idea.

So what are the outcomes from detox?

A study from Geneva of 73[i] patients with dependent opioid use followed up at one and then six months after detox found 35% abstinent at one month and 37% abstinent at six months. Residential treatment following detox was associated with increased likelihood of abstinence. Not all the lapsers/relapsers were using dependently again, but the relapse group was clearly significant in numbers. Using cocaine after detox was a risk factor for relapse.

In a 14-month follow-up study from Ireland[2] involving 143 patients detoxed from opiates, the participants were divided into three treatment types: no formal aftercare; outpatient aftercare and residential rehabilitation. The average methadone dose prior to detox was around 77mg in the aftercare groups and 69mg in the no formal aftercare group. The patient group were found to be representative of opiate replacement patients generally in Ireland. All engaged in prior preparatory work. The primary outcome was abstinence. They had a good follow-up rate of 75%.

The residential group had the lowest relapse rate. Those participants who chose outpatient aftercare relapsed at a 52% higher rate than the residential patients. The no formal aftercare group relapsed most and fastest. Interestingly, the intention to attend residential treatment post-detox had a statistically significant effect on abstinence. In the longer term the differences between the outpatient aftercare group relapse rate and the residential treatment aftercare group relapse rate began to close raising questions about cost effectiveness for the authors

The authors make the point that even with aftercare, patients were more likely to lapse/relapse than stay abstinent which raises concerns for safety. No deaths or overdoses were reported in the paper, though not everyone was followed up. The authors call for risks for lapsers and relapsers to be managed with appropriate supports.

This study both supports the proposition that achieving abstinence following opiate detox is an achievable goal for some and at the same time represents a risk for others. More than half of those in the group had undergone detox before, suggesting for some that several attempts may have to be made – again seemingly increasing the risk.

I believe there are ways to decrease the risk. Longer times in residential treatment are associated with better outcomes (some of the sample completed only 8 weeks, which is probably an insufficient ‘dose’). There is no mention in the paper of mutual aid which can have significant mitigating effects through social networking using assertive linkage to mutual aid groups like NA, CA and SMART Recovery. Nor was there reference to family therapy or even simply involving families in planning and support.

It’s also not clear what harm reduction advice was given at the outset, and again during treatment and on discharge (overdose prevention, resuscitation training, take home naloxone etc.). Nor is it clear what pathways were available for early re-entry into MAT for those who had relapsed or what was the availability of re-titration for those who wanted to leave early from treatment. The quality, intensity and duration of aftercare, and whether mental health and psychological issues are addressed in treatment and in aftercare, are likely to be important variables which could reduce risk.

I think that harm reduction interventions like overdose prevention, take-home naloxone and early MAT re-entry on relapse are crucial in reducing risk, but that the aforementioned psychosocial elements of recovery management may well be as important in risk mitigation. We have a lot of knowledge and faith in the former, but need to really work on the latter.

Detox from opioids should only normally be offered in the context of a robust treatment and aftercare package and not as a stand-alone intervention. We would not offer chemotherapy to patients on the basis of removing some of the elements that promote success and then offering no follow-up, nor would we neglect the important psychosocial factors that reduce risk of recurrence. Treatment of opioid use disorder deserves at least the same level of care.

Continue the discussion on Twitter: DocDavidM

[i] Broers B, Giner F, Dumont P, Mino A. Inpatient opiate detoxification in Geneva: follow-up at 1 and 6 months. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000 Feb 1;58(1-2):85-92. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00063-0. PMID: 10669058.

[2] Ivers JH, Zgaga L, Sweeney B, Keenan E, Darker C, Smyth BP, Barry J., 2018. A naturalistic longitudinal analysis of post-detoxification outcomes in opioid-dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018 Apr;37 Suppl 1:S339-S347.

SMART is excited to premier its new YouTube series Life Beyond Addiction. The monthly series captures inspirational stories of hope, determination, and perseverance about people who succeeded at recovery and are living a Life Beyond Addiction.

Kicking off the series is Edward Howard. He found SMART through Above & Beyond Family Recovery Center in Chicago, Illinois. There he learned and implemented the SMART Recovery tools that allowed him to build a new and meaningful Life Beyond Addiction.

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Dr. Henry Steinberger, of Madison, Wisconsin, is a long-time, trusted advisor and facilitator for SMART. His extensive educational credentials and background have been invaluable in shaping SMART Recovery into the organization it is today.

In this podcast, Henry talks about:

Additional Resources

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Hotline @ 800-273-8255, https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

On Las Meninas by Velasqez, Foucault writes, “In appearance, this locus is a simple one; a matter of pure reciprocity: we are looking at a picture in which the painter is in turn looking out at us. A mere confrontation, eyes catching one another’s glance, direct looks superimposing themselves upon one another as they cross. And yet this slender line of reciprocal visibility embraces a whole complex network of uncertainties, exchanges, and feints. The painter is turning his eyes towards us only in so far as we happen to occupy the same position as his subject. We, the spectators, are an additional factor. Though greeted by that gaze, we are also dismissed by it, replaced by that which was always there before we were: the model itself. But, inversely, the painter’s gaze, addressed to the void confronting him outside the picture, accepts as many models as there are spectators; in this precise but neutral place, the observer and the observed take part in a ceaseless exchange. No gaze is stable, or rather in the neutral furrow of the gaze piercing at a right angle through the canvas, subject and object, the spectator and the model, reverse their roles to infinity. (Foucault, 2005 [1966]: pg.5) Highlights by Acervado: https://beatrizacevedoart.wordpress.com/2014/08/08/foucault-and-painting-las-meninas-by-velazquez/

On Las Meninas by Velasqez, Foucault writes, “In appearance, this locus is a simple one; a matter of pure reciprocity: we are looking at a picture in which the painter is in turn looking out at us. A mere confrontation, eyes catching one another’s glance, direct looks superimposing themselves upon one another as they cross. And yet this slender line of reciprocal visibility embraces a whole complex network of uncertainties, exchanges, and feints. The painter is turning his eyes towards us only in so far as we happen to occupy the same position as his subject. We, the spectators, are an additional factor. Though greeted by that gaze, we are also dismissed by it, replaced by that which was always there before we were: the model itself. But, inversely, the painter’s gaze, addressed to the void confronting him outside the picture, accepts as many models as there are spectators; in this precise but neutral place, the observer and the observed take part in a ceaseless exchange. No gaze is stable, or rather in the neutral furrow of the gaze piercing at a right angle through the canvas, subject and object, the spectator and the model, reverse their roles to infinity. (Foucault, 2005 [1966]: pg.5) Highlights by Acervado: https://beatrizacevedoart.wordpress.com/2014/08/08/foucault-and-painting-las-meninas-by-velazquez/

Introduction

Why begin with Foucault’s opening on Las Meninas in The Order of Things? Quite simply because this article is both a reflection of myself, and perhaps one of you as well. This piece is also a moment of pause where I (and maybe you too), can consider where we are, how we came here, and where we are going. We are both the subject and object of our field in many ways, particularly those of us in recovery who find a situated form of knowledge embodied not just in ourselves but in those we study. We relate, strike an accord, hum an affinity, between our lives, experiences, and the work we do. We exist in multiplicity, historically, though free-floating at times in lofty balloons of “objectivity” we can instantly return duplicitously into the skin, heart, and mind of our subjects. We can possess them as we possess ourselves in ways that are not possible for many scientists in other fields. Our humanity give our brushstrokes a certain technique that is unassailable, while at the same time the colors we use may be dangerously close to real life, risking all claims to the empirical. We can reverse the roles to infinity, and this offers us insights we should share, as I will do now.

In recent years, I have expanded my education beyond the clinical and human services field into more extensive areas of social sciences such as geography, history, economics, and philosophy. Stepping outside of the SUD and recovery field has allowed me to rearticulate and renegotiate my thoughts, hopes, and ideas regarding the state of the art.

Nationally, as new money in the forms of grants and funding has flowed in to the science of recovery, along with a whole host of new faces, names, and ideas, a tremendous amount of ground has been covered in a short time. Driven by the opioid crisis, the renewed money and interest have spurred innovations, new organizations, data collection, and an avalanche of research. In 2014, I decided to pursue and promote a vision for a new science of recovery. At the time, it took me only a few months to read all the existing research on recovery (something that today would take far, far longer). In 2014, the stock of research on addiction far outweighed any discussion of recovery, hope, or community. I committed myself to changing what I saw as a gross imbalance in the science regarding the field.

A handful of legendary researchers whose names we all know had carried the entire recovery science vision between themselves, often with little money, no lab space, or awkwardly positioned within medical and clinical departments and programs. To me, these scientists were the real heroes of the field. It was so much easier to get millions of dollars to drug rats and dissect their brains than to get money to study how real people recovered from addiction en vivo.

If nothing else, the years since the mid-2010s have demonstrated a rapid and appreciable shift toward a focus on recovery dynamics as a distinct and worthy scientific endeavor. Recovery science requires a stand-alone research space, ethos, and focus. The study of recovery necessitates unique instruments, theory, definitions, models, and scientific training.

But the most crucial advancement has been the recognition and promotion of lived experience as an intractable ingredient to science, clinical design, and advocacy overtures. We must never lose our reliance on survivors as our most trusted and reliable source of knowledge.

Despite the advancements, I still have vast amounts of trepidation. Knowledge production is funded through institutional forms of political and ideological control. These forms of power are not always in our interests. We are not unlike robotics researchers who take defense money to study things that may have future military applications. In particular, federal funding has a way of pushing the field toward “acceptable” (profitable) forms of knowledge production. As we see with the COVID-19 vaccine– decades of publicly funded research, powered by idealistic scientists, grad students, and basic researchers are often just handed over, lock, stock, and barrel to private interests. I think of all the insights, late nights, coffee, donuts, failed experiments, frustrations, and ultimately that glorious feeling of laboratory success that brought us mRNA technology. I imagine the quiet egghead celebrations in cramped breakrooms of biology labs that each of those breakthroughs must have brought! Cake, drinks in paper cups, and cheers to the dedication, late nights, and good work of the team.

The story of mRNA technology and the vaccine’s evolution is quite beautiful, as is the scientific discovery process in general. In many ways, the story of mRNA vaccines reflects why most of us got into research and science. All of us working in human science research are fueled by a genuine belief in the goodness of science and the fundamental premise that persistence, applied knowledge, technique, and synthesis, can yield discoveries that can save lives, facilitate social connection, heal broken bodies, and soothe inflamed minds. To be sure, the private sector is working hard in manufacturing these vaccines, breaking through boundaries of their own, and smashing speed records in bringing COVID vaccines to market. Still, I wonder what is lost in this complete handover to the private sector. What do we lose when well-intentioned science becomes a commodity?

Any of us who have worked in the field long enough know the struggle—the balance and the challenge that exist when seeking funding and mainstream intellectual acceptance of our ideas. We risk losing control of those ideas, and we risk losing control of how these ideas are applied to the world. Sometimes, the intent is lost altogether. It is so easy for a good idea to be co-opted, stripped of its purpose, and sold as a market product enriching many except the people who thought it up, believed it to be fair and who proved such an idea was worthy of being called scientific. Sometimes good ideas are commodified in such a way that they never even reach the people they were designed to help.

As a field, we are somewhere between the days of pioneering legacy, radical experimentation, and mainstream establishment. This moment calls for a more “hack and slash” mentality—distribution, collection, analysis: deployment, incremental adjustment, redeployment— in short, a time of trial and error– one that will require significant resources and endurance.

This time is also where we begin to see the fundamental flaws of systemic knowledge production and the challenging translational application of such ideas in the real world, from funding to politics: we are beginning to see how the limitations wrought by institutions, biases, class, race, culture, methods, history, power, money, and the boundaries of established fields can delimit and negate one another. We see how forms of knowledge and power conflict, disrupt, occlude, merge, and neutralize with one another. We see the diffusion of both ideas and intentions, and we see the dispersion of will and force. We open the hood of society and see the complex machinations churning away beneath. We also witness how sometimes only parts of ideas are mainstreamed, while more comprehensive, humane, and otherwise, better parts of our concepts are discarded without a second glance by the world and its systems. We see how some ideas and specific findings have a covalent bonding potential that attracts similar ideas while repelling others. Different ideas come to rest in different places and under myriad guises, applications, and operations. We see the kinetics of social science come alive and in full detail.

We see the rise of well-intentioned medical experts and clinicians claiming territory and decrying the historical absence of their tools and expertise. And we see cultures and communities that do not necessarily need or want scientists and doctors, well-intentioned or not, treading on their space. We see the death grip of insurance companies, profiteers, and shady business promoters who have fed themselves on the blood of desperate families struggling with addiction for decades. Under the slightest scrutiny, they bare their fangs when we come promoting science and dignity as they shame their clients into submission. We lurch back in disgust and wonder how such creatures have escaped the light of day.

Most importantly, we see how the historical abandonment of all people with addiction issues has painfully and dangerously given birth to some of the most beautiful, potent, and vibrant forms of mutual-aid and community outreach that have ever existed in human history, all driven by forms of spiritual altruism, humanistic compassion, and the search for basic human dignity, rights, and the promotion of health.

And finally, we see a whole generation of newly minted researchers eager to step into freshly formed departments of recovery science popping up at institutions across the country. Recovery has in many ways moved from a social novelty into a scientific focus.

The Future:Tense

As challenges, limitations, and tensions arise, we see the age-old philosophical questions emerge about ethics, knowledge, empiricism, evidence, and morality. We cannot and should not shy away from these contradictions, disputes, and limits. There is no perfect world where money will be limitless, where all lives are saved, everyone with previous addiction issues flourishes, and everyone gets a pat on the back for collectively ending the problem of addiction in society. If you haven’t already accepted this fact, you should. Our political economy alone forbids such utopias, even if they are possible in some ways. This acceptance, however, should spur you towards something else, something more extensive and more urgent. Personally, these small challenges we face as scientists have pushed me well beyond my “own lane” into concerns about the state of science, ecology, and the future of humanity.

If you work in this field long enough, you will notice there is an invisible wall or ceiling you can’t quite seem to grasp that begins to hamper your every move. Like a mime, you feel along the invisible surface, hand over hand, seeking some edge, some way around, or through this hidden field. And hand over hand, you begin to realize the enormity of this barrier. You begin to sense how this invisible barrier isn’t just your problem. You notice that virtually everyone bumps into it and staggers away, dazed and confused, wondering what happened. As a scientist, you feel the pull of curiosity. What is this force that is holding us all back? Why can’t we seem to get the stuff that people need into their outstretched hands, even when we have proof that this is the answer?

Versions of that question can and should plague every moment of your career. And if your eyes are open, you will seek an explanation and a solution. Particularly as we move forward as a country, as one slow-rolling crisis bleeds into the next, you will begin to see that your frustration regarding the field of recovery is not unique– your frustration is part of a connected set of larger systems of power. These prompt larger questions we should all be asking.

What is state of the art today? Recovery science is taking its rightful place within the annals of science. But with that emerging development, recovery science faces the same dangers, temptations, ambiguities, and contradictions that all humanitarian endeavors face. Once desperate for funding, we see that we might be pushed in directions we did not intend now that we are flushed with cash. We see corruption abounds in equal measure to good intentions. We see tools that may help can also restrain and injure. We see our scientific jargon and beliefs can be just as dogmatic and equally misunderstood as folk knowledge and tradition. We see politicians who appear friendly, who shake our hands and congratulates us, only to cut funding the minute budgets are tight. We see institutions, organizations, and departments that are in an equal measure responsible for, and to, the forces that oppress and subjugate the populations for whom we toil. Whole areas of western thought, we realize, can be historically problematic and inhumane. We watch colleagues take up causes for the sheer profit of self-promotion. Books are written, and careers heralded in ways that make a simplistic mockery of the complexity we see growing day by day in our research.

We see and feel resistance to what we do in various ways, but we are beginning to recognize that the resistance we feel isn’t just because of what we do or who we are seeking to help. We are beginning to see how reductive our awareness has been. It isn’t just stigma. It isn’t just puritanism. It isn’t limited resources or poor management, and it isn’t just racism, sexism, or inequality that holds back the forces we are seeking to elucidate and expand in the name of good.

In short, we are beginning to outgrow our ignorance of the larger social forces that delineate what we do, how we do it, and what use is made of the things we discover, like a social worker who suddenly realizes that poverty can’t be counseled out their client, that neither mental health nor poor choices are responsible for this kind of poverty. The troubles their client is facing are instead part of a vast system of forces of which poverty is but one outcome.

We should embrace and welcome this new and growing sense of enormity and challenge. Our burgeoning awareness should be a source of strength, wisdom, curiosity, and hope. As scientists, we are some of the most powerful minds on the planet. Those of us in recovery are some of the greatest humanitarians to walk the earth presently. We should question all that holds back the efforts to alleviate pain and suffering in this world– Systematically, methodologically, forcefully, and definitively– we will advance, not just for the sake of facilitating recovery, but for the sake of society itself. And this brings us full circle folks.

A few weeks back, fellow writer and colleague Jason Schwartz posted a piece titled Meaning and purpose in the context of opioid overdose deaths. It and the related article of the same title written by outgoing Editor in Chief, Dr. Eric Strain of Drug and Alcohol Dependence deeply resonated with me. Dr Strain lists some critical questions delineated in Jason’s blog post linked above. Dr Strain also writes:

“If we are committed to helping people fully address their SUD, then we need to do more than prescribe a medication or to prevent them from an overdose. We need to help them find meaning and purpose, to grow, as we all need to grow. We should not wither or stagnate in our lives, but continue to grow in our relationships, our health, in our view of the meaning and purpose we have that gets us out of bed in the morning and engages us in enterprises that are bigger than us. We should strive for the same for those who suffer from a SUD.”

This is worth reading again. The truth of our care systems is that we do not provide the same care as we would wish for our own loved ones. We all know this. People in recovery have been advocating to change this for several decades. Those of us we who have successfully navigated our limited, flawed and fragmented care systems know that if we actually did these things – focused on assisting persons with addictions to find proper meaning, support and hope in their own lives, we would radically change our care systems for the better while saving lives and resources.

None of this is new information. Nor is the fact that substance use disorders are complex conditions. Reflective of this fact, the current definition of addiction by the American Psychological Association is:

Addiction is a chronic disorder with biological, psychological, social and environmental factors influencing its development and maintenance. About half the risk for addiction is genetic. Genes affect the degree of reward that individuals experience when initially using a substance (e.g., drugs) or engaging in certain behaviors (e.g., gambling), as well as the way the body processes alcohol or other drugs. Heightened desire to re-experience use of the substance or behavior, potentially influenced by psychological (e.g., stress, history of trauma), social (e.g., family or friends’ use of a substance), and environmental factors (e.g., accessibility of a substance, low cost) can lead to regular use/exposure, with chronic use/exposure leading to brain changes.

Despite its complexity, we treat SUDs like single substance issues with narrowly focused, short-term strategies. I have written about this at length. To provide some analogy here, if we treated complex fractures of the femur in this way, we would pin the bones and send people on their way without a cast and hope it sets itself straight. We may even suggest that the healing of the bone properly would be the patient’s choice and hope they made good decisions on bracing it. If we did that, we would have a lot of people who could no longer walk or who were limping around on bowed legs. We may even blame them for not healing their own leg properly. We have more compassion for people with broken bones than to consider such barbaric care and attitudes. In respect to substance use care this is unfortunately not the case.

People in recovery started a movement 20 years ago to fix our SUD care system and design care that met our needs. It is called the New Recovery Advocacy Movement (NRAM). Suffice it to say we still have a very long way to go. That we have made rather limited progress is instructive on the breadth and depth reflective of implicit bias against persons with substance use disorders. Essentially, our care systems do not see the persons served as having the same value as we see ourselves or our own family members. It is hard to swallow and undeniably true in the same breath.

We appreciate Dr Strain for stating what we all know. A reflective care system would consider our needs and commit to radical change. Yet what we see is like a form of cognitive inertia within our behavioral health care systems. We even experience instances where those of calling for such change are ostracized or called uneducated, the pejorative “drug addict” label silent but ever present. This is how the voices of lived (and formally educated) experience are dismissed.

Having spent my entire adult life through age 55 immersed in work to support recovery, I can tell you that very often I would get calls from people seeking more comprehensive care for their loved ones than the average person gets. The conversation invariably turns to their perception that their loved one started down an innocent path the led to addiction and their loved one is not like those others and deserved to be treated better. Their person is not like “those people.” Having treated thousands of people seeking public funded care, I know this to be entirely false. Mahatma Ghandi once said “A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.” If we want better care for our own family members, we must concentrate efforts to dramatically improve care for those who have the least. Perhaps we start with Dr Strain’s point and change care to reflect what we would want in our own lives.

Beyond one’s personal recovery, what could the general idea of recovery be good for?

To explore what the idea of recovery could be good for, I would like to separate the word “recovery” from its normal use (about people making personal changes in the face of addiction illness), and highlight some other benefits that could be found in the idea of what recovery is.

In this article I would like to turn from recovery as a personal matter and look at some other uses of the word and of the idea of recovery.

About three years ago it started to seem to me that the word “recovery” in its use as a technical term in clinical, research, public health, and policy circles had lost its window of opportunity, was no longer viable, and had probably become outmoded.

Why?

We were seeing so much public criticism from academics, professional clinicians, and various advocates aimed against:

- Twelve step recovery (as found in all its forms including A.A., N.A., Al-Anon, CoDA, O.A., etc.),

- Twelve Step Facilitation as a clinical practice, and

- both abstinence and sobriety themselves,

that I had reached an internal tipping point.

A Well-Known Name

The area of depth psychology I have drawn from for this article has an especially well-known name. That very well-known name is so well known, that the name could easily get in the way of some readers taking in my idea. So, I’ll share that name later in the article. For me, until the most recent few years, the name would serve as a major block and if I saw it I would probably stop reading. That’s how strict my education and training were, and how I was taught to think.

For now I will say that this area of depth psychology has been described as a larger meta-topic than it is commonly known to be. And in that way, it is said to be comprised of four separate, but interdependent, endeavors. It is further said that each of those four endeavors is really a separate discipline, or field of study – each in their own right.

Many people who are aware of this area of depth psychology because of its well known name are unaware of its separate application in these four areas.

To me, these four areas also apply to the idea of recovery. And to me these four areas show us some additional potential of the idea of recovery – beyond its application to one’s own personal change.

A Four-Part Framework

I suggest that we can also consider Recovery a meta-topic that comprises the same four areas, and we can borrow the same four-part framework. Each area could serve as a target of study or as a lens through which one conducts their work.

What are the four areas we would borrow?

- A method of understanding personality (its formation, development, and function, etc);

- A way of understanding the mind (its components, topography, functions, etc.);

- A method of psychotherapy (arranging and providing it);

- A topic and tool for conducting research.

With very little effort we can transfer those four areas of interest from depth psychology and apply them as four parallel areas of potential content and value within the construct of Recovery.

Four Potential Areas of Study

First of all, Addiction Recovery can be thought of as a Personality theory

- It has occurred to me that insofar as the Steps and Traditions can apply to any person (as anyone is eligible to potentially develop addiction illness) that the progenitor of 12 step recovery (A.A.) has accidentally built a personality theory.

- For example, the steps (commonly described as relation to self) and traditions (commonly described as relation to others) point to personality facets and ranges of function common to all people generally.

- Similarly, the Spiritual principles of both the Steps (as found in A.A.) and of the Traditions (as found in O.A.) point to common personal and collective values.

What could the world gain from a full inquiry into the character and personality of Recovery?

Second, we can consider Addiction Recovery as informing the topography and components of the mind: the Study of Cognition and Metacognition

- The book titled Addictive Thinking (Twerski) outlines the content and style of cognition commonly present in later-stage moderate to severe SUD’s (addiction illness). These include problematic patterns in attempts to resolve cognitive dissonance and problematic end-point cognitive schema that end up serving as barriers to recovery.

- The article titled A.A. and 12 Step Recovery: A Model Based on Social and Cognitive Neuroscience (Galanter) outlines the cognitive elements of a program of Addiction Recovery from a 12 step perspective, redefines them in operationalized terms from general psychology, and identifies the associated brain region for each.

- The book titled RecoveryMind Training (Earley) provides an outline and overview of cognitive and cognitive-behavioral changes during the earlier and later phases of recovery.

What could the world gain from a full inquiry into the mind of, and that is, Recovery?

Third, we can consider Recovery as a Method of therapy

- In his article about Recovery Carriers Bill White describes those people who function as sources of positive contagion. This contagion seems to derive merely from recovery itself, within and through their person. He describes the content, process, and “lift” provided to others, that is brought about by recovery.

- Culture has been examined not as a helpful context or frame, but as the treatment itself. It is axiomatic that the majority of people with lifetime substance use disorder recover without formal treatment. Recovery culture is an active therapeutic ingredient, and can be found across people groups.

- Carl Jung and Bill W. corresponded and some of those letters are available for us to study. In one letter, Jung outlined what is tantamount to a cultural framework as his curative suggestion to Bill W. If you read those letters, Jung’s ingredients will probably be surprisingly familiar.

For clarity I will say that evidence-based counseling methods like Twelve Step Facilitation and Motivational Interviewing are excluded from what I am aiming at here. Rather, I mean to focus on recovery itself (recovery that is modeled, caught, and practiced) as the therapeutic agent.

What could the world gain from a full inquiry into Recovery as the therapy?

Fourth, we can apply Recovery as a Research method

- The value of experiential knowledge as data has been outlined by various researchers (Borkman’s 1976 paper comes to mind).

- Styles, pathways and varieties of the recovery experience have been outlined, (Bill White’s book and papers on this topic come to mind).

- In the book Recovery Rising we are told the story of Bill White’s “epiphany in Dallas” as an A.A. old-timer encouraged him to study recovery itself, and not just treatment, and not just treatment outcomes.

- One dream project I have longed for over several years would be to have Artificial Intelligence read the entire approved recovery literature and aggregate the indicators it contains within and across all the Stages of Healing.

- The NA text titled Living Clean: The Journey Continues serves to me as information obtained during recovery, but from the perspective of traveling in recovery over time. It is as if the writing provides a view from the point of view a time voyager. It opens us to the notion of potential content that could be gained only from the continuity of data, and the continuity of data collection.

What could the world gain from a full inquiry using Recovery as a research method, not just a research target?

A word too common to understand?

What was the area within depth psychology whose name might have gotten in the way if I had revealed it? That word is Psychoanalysis. Within its complete scope, psychoanalysis as a field of study is properly understood to function separately and together as a:

- theory of personality,

- way of understanding the mind,

- method of therapy,

- and tool of research.

To me, Recovery is like that, and also has potential in those same four areas.

Like “psychoanalysis” (when understood within its complete scope) “Recovery” could be considered to include a theory of personality, a way of understanding the mind, a method of therapy, and a tool of research.

Thus, Recovery could be understood to include far more than only the personal matter of one’s wellbeing that the word “recovery” commonly conveys.

My Wish List

Personality.

Do we have a text examining the domains and function of human character and personality – through the lens of recovery? What is the collective and potential constellation of the personality of recovery?

- Currently my favorite more modern texts on the topic of Personality formation and function are Character Styles (Stephen Johnson) and The New Personality Self Portrait (Oldham & Morris).

Mind.

Do we have a text describing the topography and function of the mind as seated in recovery?

- My favorite classic article about the operation of the mind is Negation (Freud).

- My favorite more modern text on the topic of the topography and function of the mind is The Unthought Known (Bollas).

- To me, the clearest overview of the value of this area of the topography and function of the mind is Freud’s writing on the topic of metacognition.

Therapy

Do we have a text describing the arrangements before and during the provision or transmission of healing found in recovery?

- Pertaining to analytically-oriented therapy, my favorites articles include Winnicott’s work titled Fear of Breakdown and Bion’s piece titled Notes on Memory and Desire.

Research

Do we have a text informing us of recovery itself as a research method?

- As for research in the analytic tradition my favorite classic texts are Kohut’s book “How Does Analysis Cure?”, and one by Freedman and others titled “Another Kind of Evidence.”

A Recurring Worry

In spite of the latent potential in these four areas/methods of inquiry, I remain uncertain as to the future of the word Recovery.

In a compelling study from Dublin, Paula Maycock and Shane Butler (Trinity College) make the point that little is known about the stigma experienced by individuals attending drug treatment services over prolonged periods. They explored this through the lived-experience narratives of 25 people prescribed long-term methadone. Their findings ‘reveal the intersection of stigma with age as profoundly shaping methadone patients’ perspectives on their lives’.

I like qualitative research because it is often affecting – stories bring to vibrant life important things we need to consider. You remember stories. You remember the feelings they engender. I connect with qualitative research in a way I never can with tables, graphs and statistics. I connected emotionally with this study.

In this study, 16 men and 9 women were interviewed. Two thirds were over the age of 40 and 16 of them had been on methadone for 20 years or more. Two were now long-term abstinent from all drugs including methadone. Nine people were attending a clinic for daily supervised consumption. Only three of the 20 were employed full-time.

The findings of this paper did not make for an easy read. You can sense something beyond detached academic curiosity here. Butler and Maycock reflect:

An intensity permeated these narratives in the sense that interviewees frequently – and, at times, emotionally – recounted treatment-specific experiences that engendered a sense of ‘otherness’ and shame.

Maycock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 2021

Methadone was seen as an instrument of punishment, ‘reflecting and amplifying’ public stereotypes around drug use and addiction:

It’s so demoralizing to go into the clinic and you’re just, you’re pissing [urinating] in bottles and grovelling to your doctor and grovelling to the chemists and that was your life, that was my life, you know.”

Rachel, service user

The research participants describe feeling ‘not normal’, having to ‘duck and dive’ and being treated ‘like dirt’. The absence of connection with the professionals they had contact with seems astonishing to me and the perception of being controlled or punished by the ‘techniques’ of treatment – e.g. threats of removal of takeaway doses for ‘dirty urines’ – was upsetting. Bad experiences reportedly extended to pharmacies where ‘public shaming’ took place.

The relationship with age and time on MMT (methadone maintenance treatment) was explored – there was a particular shame around being on methadone at an older age or for a longer period of time, such that individuals wanted to hide this, in a way that did not apply to other prescribed medications for other conditions.

The most harrowing theme in the paper is what Mayock and Butler call the private burden of stigma – the pernicious inner voices suffered by the participants, instilled powerfully and cemented down by years of reinforcement. The result is diminished spirit, low self-esteem and an erosion of humanity .

That’s what you do as a drug addict – you let people down, you’re unreliable, you’re of fucking no use to nobody.

Cormac, service user

The authors’ conclusion is hard hitting:

The lived experience of long- term MMT in Ireland is one characterized by relentless stigmatization, reflecting the marginal position of addiction treatment within the wider healthcare system and a failure to normalize methadone treatment.

Maycock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2021

It’s impossible not to have a strong reaction to this paper – it made me angry and sad and frustrated, but we do need to be a little careful here. The numbers are small, this is only one area of Ireland, and we are not hearing the other side of the story – how providers might see the situation and what limitations and duress they are working under, but that said, this is powerful stuff which merits consideration and further research.

So, what’s to be done?

The authors identify some issues specific to Ireland relating to the introduction of MMT which may be partly responsible, and they welcomed a policy shift away from criminal justice approaches towards a health approach, accepting that the tensions between the two are difficult to erase. They question the impact of a public campaign to tackle stigma, instead calling for organisational change in clinics and social structural change outside of treatment settings. Perhaps the most profound challenge they give us though is what we do with the upsetting legacy of what we’ve read in this paper.

I come back to a concern that bothers me here: the tension between what’s good for public health and what individuals want from treatment. The subjects in this research can’t have entered into treatment because they were seeking public health benefits from MMT – they would have wanted to see their lives getting better. The authors acknowledge this explicitly:

The well-documented public health benefits of MMT were not matched by a perceived improved quality of life among this study’s methadone patients

Maycock and Butler, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2021

Maycock and Butler have looked at this in more depth in a separate paper (which I’m planning to come back to a different time) where people (the same ones I suspect) on MMT report being ‘passive recipients of a clinical regime that offered no opportunity to exercise agency’. This observation fits in with studies from elsewhere prompting the development of a large scale study looking into quality of life of those patients in treatment on MAT recently announced in the British Medical Journal.

While methadone and other examples of MAT have strongly evidenced benefits, medication does not offer meaningful healing for hurts. Methadone is not the problem here, nor is this only about stigmatisation. If we give methadone the blame we miss a trick.

I was struck by the absence of any meaningful interventions reported in the clinical settings where methadone was dispensed. Where was the compassionate approach to trauma? Where were the practical supports for housing, benefits, employment, families? Where was the mental and physical health support? Perhaps it was there but not reported, which says something in itself.

What would it have been like, I wonder, if the individuals had been offered meaningful support and interaction in each setting – primary care, clinic, pharmacy – by peers with lived experience? There is a call by the authors for involvement of stakeholder groups committed to harm reduction, but why not committed to harm reduction and recovery? Harm reduction is essential, but it’s not an end in itself. I have written recently about this quoting Eric Strain who talks about the importance of finding meaning and purpose and allowing people to ‘flourish’ in treatment.

So why not have peers on MAT, for instance, who had achieved their goals from treatment. Or peers who had moved on from MAT to abstinence? Or a mixture. What if clinics were perfused with hope and that hope was embodied in peer role models who had knowledge and experience of moving on and developing – of flourishing?

I have another concern. The word ‘recovery’ appears only twice in the text – once in a document title, and once as a point of tension where harm reduction approaches have to be defended from an attack by ‘the recovery model’. I might have picked this up wrongly, but the implication seems to be that recovery models are part of the problem, something I’ve also heard from some authorities here in Scotland.

The proposed solution – that stakeholders argue ‘overtly, explicitly and strongly for public support and acceptance of methadone as a legitimate and effective form of addiction treatment’ misses the point, in my view, that the prescription of methadone alone will never fulfil that goal, because it’s what goes alongside the prescription that brings positives into lives instead of simply reducing the harms.

I would argue that the introduction of recovery-oriented systems of care, (including medication-assisted recovery as an integrated component), rather than being a threat here, have the potential to transform the structures that have led to this degree of stigmatisation. The absence of hope in treatment systems is not only damaging to service users, but to those working in services. It’s easy to get burnt out. We need to set the bar high not just because we value those we work with, but because we also value ourselves.

I’ll leave you with something hopeful I quoted in a recent blog about stigma.

The most effective strategy for combating opioid use disorder stigma may be to avoid a rhetoric of hopelessness, and instead emphasize the recovery potential of affected individuals and communities.

Perry et al, Addiction, 2020

Continue the discussion on Twitter: @DocDavidM

Paula Mayock & Shane Butler (2021): “I’m always hiding and ducking and diving”: the stigma of growing older on methadone, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, DOI: 10.1080/09687637.2021.1886253

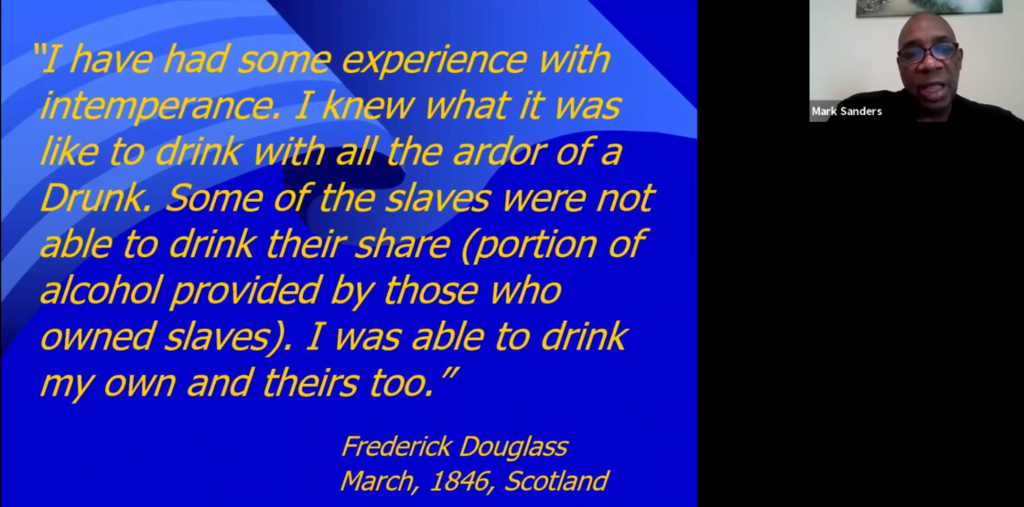

The Association of Recovery In Higher Education recently hosted a webinar on the The Recovery Legacies of Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X.

It was presented by Mark Sanders, an under-recognized treasure in the field.

I can’t embed it here, but please go check it out.