Hands holding binoculars on green background, looking through binoculars, journey, find and search concept.

Protecting your recovery at all costs must be emphasized at all stages of recovery. Relapse starts well before a person picks up using a drink or a drug, so developing insight into your relapse triggers is a concept that needs continual assessment and evaluation during and after treatment. You may ask, “What the heck is a trigger?” A trigger can be best described as a person, place, thing, feeling, or situation that leads to a thought that taking a drink or using a drug would be a good idea.

As a person in recovery, it is your responsibility to identify and be aware of your own triggers. A trigger prompts a thought, which if it is romanced, can become a craving. Smash that thought, play the tape to the end, and remember the pain you felt in active addiction. Remember the H.A.L.T concept. When you become restless, irritable, and discontent, continually ask yourself, “Am I hungry, angry, lonely, or tired?” If so, these feelings could increase the risk of relapse. Only you have the power to address these feelings with the recovery tools you now possess.

We encourage people new to recovery to focus on developing healthy communication skills and learning to be emotionally intimate with peers before diving head first into a relationship rooted in physical attraction. In early recovery, the newcomer is still early in developing healthy emotional coping skills. Romantic relationships and sexual acting out can detract a person from focusing on sobriety and often leads to a quick relapse. Most addicts and alcoholics have used alcohol or drugs to cope with emotions. The newcomer is an infant in emotional sobriety. Talk about feelings openly in meetings and with a sponsor. Most people will never heal what they do not feel.

Living in recovery will give you a life worth living. Be aware of complacency, euphoric recall (thinking back to your drinking or using with happiness or nostalgia), and forgetting the pain that addiction has caused. Be conscious not to drift away from recovery. Regular AA and NA attendance is extremely important. It’s an easy and common mistake for people to reduce meeting attendance, stop calling a sponsor, or just stop going to AA/NA altogether! Again, recovery gives people a great life that can end up taking them right back out of recovery when life improves. Remember, the brain chemistry has been changed. You will be triggered at some point in time. Tell on your disease before a trigger is romanced into a craving. Remember to continually assess your motives for being around certain people or going certain places. Think before you drink or use. The time to call your sponsor is before, not after! One Day at a Time.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The post Staying on the Lookout for Relapse Triggers appeared first on Fellowship Hall.

Ok… let’s talk.

A company called Ophelia Health has launched a new marketing campaign focusing on the message “F*CK REHAB”.

On the one hand, there’s A LOT to criticize in the addiction treatment world. At the provider level, there is a long history of really bad, predatory, poor quality, and abusive treatment springing from ineffective models, stigma, profiteering and exploitation. At the system level, we’ve never had real parity with care for other diseases, adequate funding, and cohesive systems of care.

Examples include tonic cures, cults (see also here), patient brokering, lobotomies, exorbitant lab fees, abusive teen programs, and cash-only office-based treatment. Some examples include treatment models or delivery methods that are inherently flawed and unethical, or ineffective under any circumstances. Other examples involve issues with quality, intensity, duration, or the integrity of the provider.

Bill White described 1980s treatment providers losing their way as they shifted from mission-oriented organizations to profit-oriented.

In the 1980s, addiction treatment programs shifted their identities from those of service agencies to those of businesses. A growing number of for-profit companies that measured success in terms of profits and quarterly dividends–rather than treatment outcomes–entered the field….

…Their self-images shifted from those of public servants to those of health-care entrepreneurs. For a time, a predatory mentality became so pervasive that it affected even some of the most service-oriented institutions. In this climate, alcoholics and addicts became less people in need of treatment more a crop to be harvested for their financial value. This evolving shift in in the character of the field left in its wake innumerable excesses that tarnished the public image of the field and set in motion a financial backlash that would lead to fundamental changes in the primary treatment modalities available to addicts and their families.

William White in Slaying the Dragon

I assume that Ophelia’s use of “rehab” refers to inpatient and residential programs, which dominated the industry in the 1980s. Over the last couple of decades, many residential programs have been among the worst offenders, with exorbitant rates, misleading marketing, inadequate duration of care, poor quality monitoring, and, in some cases, fraud. That there have been serious problems in residential programs does not mean that residential programs are universally problematic.

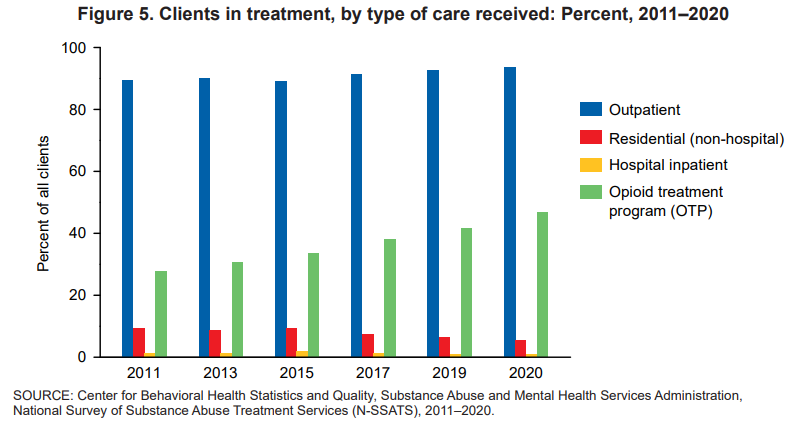

It’s important to note that residential and inpatient make up a relatively small and shrinking fraction of the treatment provided in the US today. (Note that this graph represents ALL clients, not just clients with opioid use disorders.)

Between 2011 and 2020, the proportions of clients in treatment for the major types of care—outpatient, residential (non-hospital), and hospital inpatient— shifted. Clients in outpatient treatment increased from 90 to 94 percent while clients in residential (non-hospital) treatment declined from 9 to 5 percent. The proportion of clients in inpatient hospital treatment ranged between 1 percent and 2 percent from 2011 to 2020

National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2020

I spent 25 years as part of a program that included outreach, outpatient, peer support, detox, residential, housing, and linkage to primary care that would help monitor recovery. We also took informed consent very seriously, with repeated discussions about the treatments we offered and didn’t offer and active linkage to treatments we didn’t provide. More recently, I spent 3 years as part of an inpatient unit that inducted a lot of high severity and high chronicity patients on agonist treatments. Programs like those — that provide rigorous informed consent and a continuum of long term care, or routinely initiate agonists — may represent a minority of inpatient and residential providers, but they were not alone.

Is “rehab” bad and telehealth good?

Ironically, digital behavioral health providers (Ophelia’s business category) have gotten some attention lately.

First, the Wall Street Journal reported on quality problems and prioritizing profits and the next round of venture capital over ethics and standards.

“When you put venture capital money into this mixture, it really pushes people to take risks,” Ms. Moore said. “It’s one thing to be a disruptive innovator, but there’s a reason medicine is encumbered by so many regulations — we’re dealing with people’s lives.”

Winkler, R. (2022, December 19). The failed promise of online mental-health treatment. via TheAustralian.com.au; The Oz.

A few months ago, a JAMA study was published and lauded as evidence for the effectiveness of MOUD (medication for opioid use disorder) treatment delivered via telehealth.

In a post about that study, I framed its findings as follows:

I want to make it clear that I harbor no skepticism about the importance of telehealth services as part of an effective system of care. With the explosion of telehealth during the pandemic, I’ve seen the benefits of telehealth in the engagement and retention of patients who might never try in-person services or stay engaged with in-person services for reasons as varied as transportation, scheduling, temperament, and medical or psychiatric comorbidities.

The study looked at medication retention and medically treated overdoses before and during the pandemic, with the before-pandemic group representing office-based care and the during-pandemic group representing telehealth care. They found good news and bad news.

The good news was that shifting to telehealth did not adversely impact either of these outcomes.

The bad news was that I found the outcomes to be very disappointing.

Retention rates for buprenorphine (defined as use over 80% of days) over 6 months were 31% for the office-based group and 33% for the telehealth group.

Retention rates for extended-release naltrexone (defined as use over 80% of days) over 6 months were 8% for the office-based group and 12% for the telehealth group.

18% of each group experienced a medically treated overdose during the study period.

The subjects were all Medicare patients. They had to meet age or disability requirements to enroll. However, the retention rate is not inconsistent with what I’ve seen in other studies with other populations.

I imagine most patients and families are looking for treatments that offer better than a 1 in 5 chance of an overdose, and 2 in 3 chance (or 9 in 10 for extended-release naltrexone) of discontinuing treatment within 6 months.

Are those outcomes explained to patients? Are they offered other options?

This criticism isn’t about the treatment being offered (in this case, medication) or the method of delivery (telehealth or in-person). My criticism is about the system of care that doesn’t offer treatment and recovery support of adequate duration, intensity, quality, and scope. (This is the norm whether you’re entering residential, outpatient, or office-based MOUD.) Further, it’s representative of an evidence-base that tends to speak only to outcomes like medication retention and overdose.

Treatment as usual isn’t cutting it (same for research as usual)

Ophelia’s “F*CK REHAB” evidence

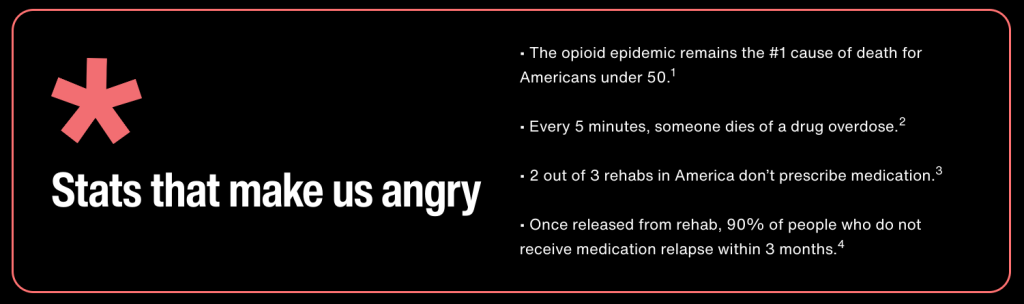

Ophelia offers limited evidence for their marketing campaign. The screen capture above provides 2 bullets that speak directly to “rehab.”

- The first states that 2/3 of “rehabs” don’t prescribe medication.

- The second reports that “Once released from rehab, 90% of people who do not receive medication relapse within 3 months.”

Both points cite the same source: Bailey, G. L., Herman, D. S., & Stein, M. D. (2013). Perceived relapse risk and desire for medication assisted treatment among persons seeking inpatient opiate detoxification. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 45(3), 302–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.04.002

So, what does this article actually say?

The article is a strange choice to support this marketing message and their characterization of it is equally strange.

- It’s 10 years old, based on 12 year old surveys.

- I don’t see where it reports anything about the number of rehabs that prescribe or don’t prescribe medications.

- I don’t see where it reports 90% relapse rates within 3 months for people who don’t receive medication, but it does say that 90% of subjects reported relapsing within 12 months of their last detox episode. It doesn’t say whether they received medication in that previous detox experience.

- However, these subjects were current detox patients, therefore 100% of them have relapsed since their last detox episode.

- This study was done with patients currently in a detox program (average stay of 5.9 days) to evaluate their desire for MAT and to investigate the factors that influence this desire.

- This detox program provided methadone tapers, educated patients about MAT, and offered MAT to all patients. They asked about previous detox experiences to evaluate the influence of previous detox experiences on their perception of relapse risk and how that perceived risk influences their preferences for or against MAT.

- Even after a discussion of their relapse history and education about MAT, 37% of patients did not want medication.

- This was not a medication-naive group, many of them had previously received MAT: 43% methadone maintenance, 42% prescribed buprenorphine, and 6% Vivitrol.

So… the article doesn’t say what Ophelia said it said and it really doesn’t even seem to speak directly to their argument.

Ok. So, what about “rehab”?

They never really define rehab, but the study they direct us to focused on a 6 day detox program that tried to connect patients to ongoing care, including medications. (It’s worth noting that this was in 2011 and use of MAT has only increased in the years since.)

I think it’s fair to criticize many residential and inpatient programs, and the opioid crisis has increased the stakes for inadequate and shoddy treatment. I’d agree that detox that is not tied to long term care is unethical. I’d say the same thing about a 30 day destination programs that don’t include assertive long-term care.

However, the model with the best outcomes often includes residential treatment as part of the episode.

Further, our colleague David McCartney reviewed a recent Scottish report on residential rehab that found:

Rehab is linked to improvements in mental health, offending, social engagement, employment, reduction in substance use and abstinence. There is little research that compares rehab with other treatments delivered in the community, but where there is, the evidence suggests that “residential treatment produces more positive outcomes in relation to substance use than other treatment modalities.” The review also suggests that rehab can be more cost-effective over time than other treatments.

Where does this leave us?

The study Ophelia directs us to found a significant minority of patients do not want medication, despite considerable experience with medication among the subjects.

The JAMA evaluation of telehealth MOUD treatment found 67% dropped out by month 6, and 18% overdosed.

A Wall Street Journal investigation demonstrated that deficiencies in quality and ethics are a significant problem in digital behavioral health. (As has been the case in other treatment approaches.)

Years ago, having reached the conclusion that there is no silver bullet in addiction treatment, I came to believe that the only responsible systemic approach is to:

- offer a complete array of services;

- of adequate quality, intensity, and duration;

- by people who believe patients can achieve full sustained recovery (or flourishing);

- provide accurate information on their options (and the options not offered);

- let them choose the treatment approach that best fits their preferences and goals; and

- allow them to change their mind as they experience successes and setbacks, and their preferences and goals change.

I’ll leave you with a couple of thoughts from colleague David McCartney.

First, some of his thoughts on polarization in the field of addiction treatment and recovery support:

When those new to the addiction field question how unhealthy it seems, we all ought to sit up and take notice. We are responsible for the culture we have created. If that is a culture of conflict, we need to attend to it. Leaders have a particular responsibility here – we ought to be held to a high standard of behaviour and professionalism. That need not make us impotent, but rather be mindful of the power that we hold and how we use it. Change starts with ourselves.

There’s one more thing – another value – that is missing when there is turmoil. That value is humility. It’s not reasonable to expect that we all agree on everything all the time. This would be a disaster – we need to feel discomfort, disagreement and passion; these can be potent drivers for positive change, but perhaps a little bit of ‘I could be wrong and others right’ would go a long way to pour oil on troubled waters.

Polarisation, tension and hostility: just another day in the field of addictions.

Finally, from his post examining the effectiveness of residential rehab:

We don’t need to say one thing is better than another, but we do need choice and through shared decision making we can try to help patients align themselves to a treatment option that helps them meet their goals. And we need to be humble too. Evidence suggests that over a lifetime, most people resolve their problematic use of substances. When they look back, they may be grateful for the part that treatment played in their recovery, but it is likely that it will be only one of many factors that helped.

For the moment though, we can certainly challenge the voices that say ‘there’s no evidence that rehab works’, for there is ample evidence that it does. I’m not unrealistic about this though. As I’ve been writing, I have been mulling over the wisdom of Ahmed Kathrada’s observation: ‘the hardest thing to open is a closed mind’. That shouldn’t stop us trying.

Over the course of my decades of work in the SUD field and as a person in recovery, I can honestly say that I have tried as hard as I can to do my very best to serve people in need of help with a substance use condition. I suspect most others in this field share this same ethic. I would also tell you that despite this level of dedication, over the years I have occasionally found that I harbored deep-seated, hard to spot, negative views about people with addictions. They came out in ways that I was not always able to recognize at the time. I suspect I am not alone in this either.

Recently, I worked with a group of researchers in a focus group examining barriers and strains on addiction treatment at the national level. There were other people from across the United States on the call with truly horrific experiences in our service system. An unfortunate yet far too common experience. For readers, please know that there are a lot of caring people who do their best with all the limitations faced to serve people. However, it is also true that one does not have to dig very far to hear horror stories of poor care and punitive treatment posing as help. As the discussion ensued, we agreed that if we ended up getting rid of our entire SUD workforce and care system and rebuilding it, we would likely end up in the very same place. The changes we need to make are more foundational.

There are bodies of research on how even people in recovery look down on ourselves and each other as a result of the all-encompassing stigma in our society. These hidden attitudes are known as implicit biases, and they are everywhere. We really do not know what we don’t know, and they influence everything we do. We must do a better job of identifying it and addressing them to move forward. Anything less simply will not work.

Over the course of my decades of work, I have consistently found that the root cause of most of our challenges is the deep negative perceptions in America about addiction and recovery. The widely held and far too often verbalized belief that we are “those people who did this to themselves” and that people like me ultimately do not deserve help. It is why we provide care at shorter durations and lower intensity than needed and fail to invest in authentic recovery supports in our communities. As a result, fewer people than should find recovery. This is a negative feedback loop that validates to a relatively hostile society that we do not actually get better, leading to even more suboptimal care.

The unblemished truth is that many people in our society openly look down on us. As I have noted in past writings, my organization, PRO-A did a large survey on perceived stigma nationally with RIWI and Elevyst. Our report, HOW BAD IS IT, REALLY? Stigma Against Drug Use and Recovery in the United States examined perceived stigma and found that 71% of Americans believed that society sees people who use drugs problematically to be outcasts or non-community members.

Three out of four respondents perceived that society sees us as outcasts. I see it with my own eyes. I have heard people around me say horrific things about people like me. Consider “take the drug addicts out to the hospital parking lot and shoot them.” People die every day from these attitudes. We found somewhat lower rates of endorsed stigma on a more recent study of medical stigma in the US, but much higher than we would like to find. These attitudes are everywhere.

They can be very subtle or in your face. It was what Kristen Johnston spoke about when reading the epilogue of GUTS ten years ago when a friend told her to stay silent about her recovery because it made people uncomfortable. It can look like punishing a person for not responding to the limited services offered. Medical staff who call someone who has experienced multiple overdose reversals a “frequent flyer” and families told to practice “tough love.”

To see implicit bias in action we need to look no farther than a service system that offers less care than the evidence has shown time and time again people need to get better. As Nick Hayes notes in his recent STAT News piece, For addiction treatment, longer is better. But insurance companies usually cut it short. These same systems hammer providers to offer evidence-based care and then, despite the evidence fund services in such a limited fashion that they can’t help. This results in poorer outcomes, which validates the belief that people like me do not heal, resulting in more of the same.

While it is clearly our biggest barrier, the pathway forward is murky. As psychologist Anthony Greenwald explains in making people aware of their implicit biases doesn’t usually change minds. We really don’t have much in the way of evidence-based practice to effectively address implicit bias. He suggests that leaders of organizations need to care enough to track their data to identify where disparities are occurring. Then they need to make changes and examine the next cycle of data to see if things improve. Practices that take commitment and long-term effort.

It is vital that all of us, and all of our institutions, particularly those dedicated to helping us examine how their internal negative perceptions about people who struggle with substances influence policy and practice. Subtle or not so subtle beliefs rooted in moralism, racism and a host of other “isms.” We make it hard for people to get well because of these deeply seated and pervasive negative attitudes. We are often not even aware of these subtle beliefs influences everything we do. These are the foundations are whole SUD care system is built on and it is why over time we tend to set up the same punitive processes over and over across history.

This article, Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. found that healthcare professionals exhibit the same levels of implicit bias as the wider population. We are increasingly focusing resources on integrating SUD services into institutions that harbor deeply held negative views about us. It is clear it will fail unless we reduce the underlying biases and change the culture.

Work is being done within the National Institute of Health to explore effective efforts to address implicit bias. We have a long way to go as noted in this 2021 NIH document, Scientific Workforce Diversity Seminar Series (SWDSS) Seminar Proceedings – Is Implicit Bias Training Effective? It suggest comprehensive approaches must be used and that compulsory single episode trainings are largely ineffective. This may seem prohibitive until we consider that it is virtually certain that if we do not do so, nothing will change.

We must commit to over the long-term to getting rid of the negative perceptions that exist nearly everywhere about addiction and recovery. An example of a place to focus such efforts is the work towards developing recovery-oriented systems of care. Legitimate work in this arena would dedicate resources to finding and addressing implicit bias against persons who experience substance misuse and those of us in recovery at all levels. This would include how such programs are designed and implemented or they will invariably become tools of oppression, because that is how powerful these forces play out across every corner and crevice of our society.

As Wellbriety elder Don Coyhis noted, “all organizations are perfectly designed to get the results they get.” if we want different results, we must redesign the system. This is profoundly challenging. Even systems that do not work offer benefits to those vested in keeping it just the way it is.

To build a system of care that gets more people into wellness, we must dig down deeper and put our institutions on foundations firmly anchored on the bedrock of positive regard. To build a system with recovery at the center. To set up checks and balances to ameliorate the profound impact of these negative views within us all. Not a new concept, just one we have never implemented perhaps because it seems hard thing to do. Instead, we keep trying to build programming on the shifting sands of implicit bias that then erode our capacity to heal.

Processes that perpetuate the system we have:

- Ignoring disparate and discriminatory processes within our systems.

- Lack of transparency in system design, implementation, awarded funding and evaluation.

- Only including impacted recovery communities as proforma participants or not at all.

- Developing programming that ignores feedback from negatively impacted groups.

To move things forward we would need to have:

- System leaders who openly look for blind spots and seek feedback on remediation.

- Disparities in system design and implementation openly acknowledged.

- Systems that develop and fund services transparently.

- Processes in place to identify and address biases within every institution.

- Impacted groups invited and engaged in resolving disparate policies.

- Open cultures dedicated to reducing negative perceptions about persons who misuse substances.

- Diverse communities engaged at all stages of care system development, deployment, facilitation, and evaluation.

Millions of Americans have found recovery. Recovery has profoundly improved our lives and helped us to be better family and community members. All of this has occurred within a system of care that is built on a foundation of stigma. It speaks to the power of recovery that people heal, often despite the system of care rather than because of it.

Imagine what we could accomplish if we addressed the underlying biases in our society that make it hard for people to heal. They are present everywhere, but it is most likely that if we started to address them in our systems of care, we can start to effect change and build a better care system.

The stakes are high. The hard to argue truth is that unless we do so we will keep rebuilding flawed care systems. It may be hard, but not nearly as hard on our society as not doing so.

by Nena Butterfield, PhD, RN, BSN and Brian Coon, MA, LCAS, CCS, MAC

This post was originally published at the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers (NAATP) website Resources/Blog section on 01/12/2023. It is reposted here with permission.

Initiating and cultivating a participant registry with maximized participation of the persons served requires intentional methodology and consistent attention. For participant registries of people following treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs), the methodology must consider what we know about characteristics of the addiction disease process and effectiveness of the clinical treatment model. SUD treatment providing organizations can seat their participant registries in their treatment practices and embed data collection within a current treatment model. So what does this mean for collecting data, participating in research, and reacting to evidence based findings in the clinical sector?

SUD treatment centers keen to contribute to evidence-based treatment models can integrate data collection into the services they provide, with outcomes of treatment recursive to care, by first adopting a long term model in the form of continuing clinical care, recovery coaching, or alumni support services. These teams serve the recovery support of the person served by completing phone calls to them at specific time increments (e.g. months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 post-acute care) that are fundamentally formative in the person’s recovery trajectory. The service is promoted to the person served from the initial pre-admission pitch of the organization’s treatment model, throughout treatment, and during the exit process.

An organization’s participation in evidence-based research can be presented to potential patients at the admissions and marketing levels as an important asset in the organization’s commitment to informing and implementing evidence based-practices and innovative measures towards improving care. This is a practice and attitude that is widely adopted in primary healthcare and can be spread within the SUD services arena.

The admissions process is an opportunity to discuss with the patient how the organization measures each individual’s progress and treatment outcomes, and how these data are analyzed and used. Organizations can reiterate that this process does not involve any change to the normal treatment plan, but simply allows the organization to make meaning of data that is collected during treatment and continuing care. Clients can be introduced to relevant staff who will be implementing the calls while the person is still participating in treatment. The caller can be introduced to the client as their personal liaison and source of support following completion of the acute-care treatment phase. During the pre-exit process, the participant can be reminded that they will receive calls from their liaison as a normal part of the continuing care model that is committed to the support of the person in their recovery process. The final of the initial touch points occurs when the first call is made by the liaison.

A recipe for success employs fundamental principles of behavioral psychology that reinforce the participant to continue answering the calls and discourages the client from wanting to discontinue the service. Callers should open the call with warmth, a genuine intention to serve, and a sense of authenticity and integrity to gain nothing from the call of personal or organizational benefit. In practice, some aspects of the call should include a friendly and casual tone that inquires after the well-being of the client following listening, and is removed from asking the person formal questions in a rote manner directly from the survey sheet. The caller should prioritize listening, rather, and encourage the client to speak freely and liberally. While listening the caller can glean many of the desired points of information needed to assemble meaningful data. The caller can take notes on unique points of conversation to utilize in future calls to create an environment where the person feels heard, remembered, and prioritized. Notes can be taken on events that arise and are perceived to be problematic and those that are especially effective. Points should be discussed in routine team meetings and incorporated into a flexible and evolving model of data collection and continuing care. Calls should be long enough to gather the necessary information and create a relaxed energy, but not so long the person called feels overwhelmed or fatigued with the process. Research has demonstrated that a call time of 20 minutes or less is generally ideal for achieving those goals.

Creating and maintaining a participant registry that is valuable to informed care can be a simple process with a clear path to success. Leaders can measure incremental impacts of successive changes toward reaching the numeric goal of the desired reach and response rate. Fundamentally, however, if the organization commits to an authentic purpose to serve and improve, to collaborate on a higher level for the greater good of recovery treatment, and tends the garden of participants diligently and with warmth, there will be growth in the field and improvement for the future.

A recorded lecture by the authors of this blog, entitled ‘Using Recovery Management Practices and Principles to Improve Your SUD Outcome Call Purpose and Method,’ is available at the following link.

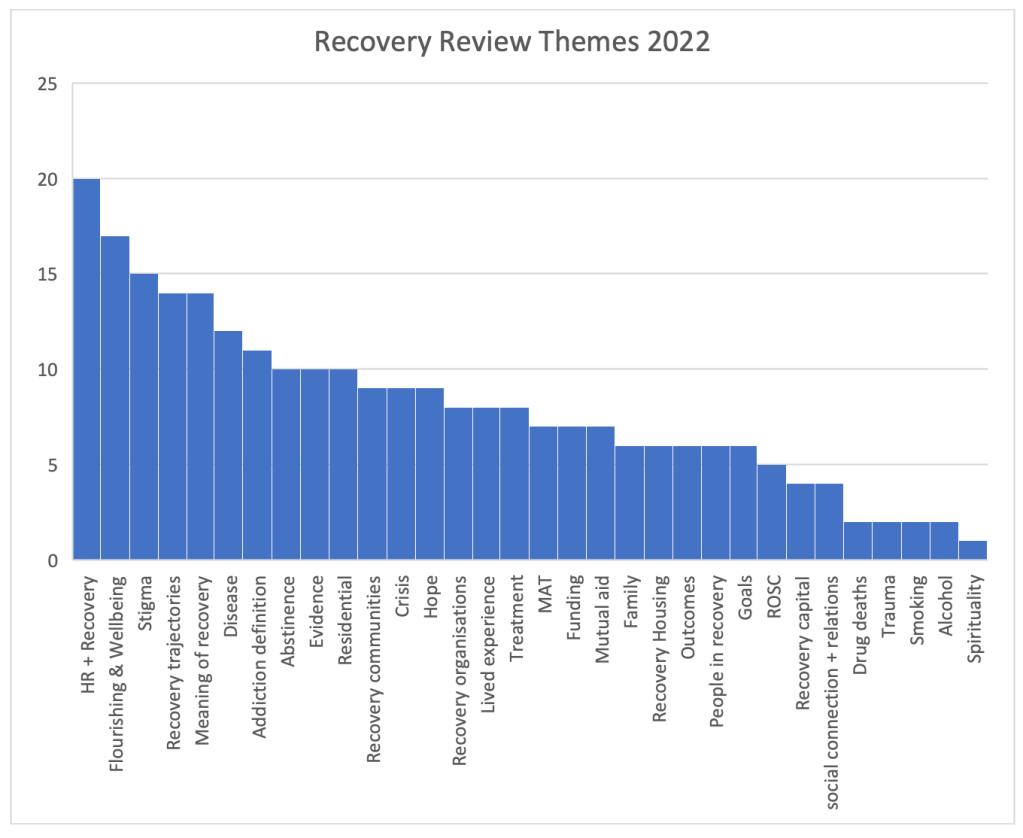

What were the hot topics, burning themes and searing subjects in addiction recovery in 2022? I thought it might be interesting to take a look at the talking points on Recovery Review in 2022.

Although the writers are very different people and we span the Atlantic, all of the contributors to Recovery Review have a keen interest in recovery from addiction and write passionately on relevant issues.

Each blog typically gets read scores of people reading it and often many hundreds – amplified when they are posted elsewhere. I hope that as well as passing on evidence, we also make people think.

So, what were we talking about in 2022 and does that tell us anything about what is really important in the field? More importantly, what’s the relevance to those seeking recovery and those supporting them to move on? I’ve done a not-very-scientific analysis of the most frequent themes across the blogs which is represented in the graph below.

Without doubt, the most commonly recurrent issues were around harm reduction and recovery. While Recovery Review consistently acknowledges the importance of harm reduction and emphasises that there is no need for polarisation, there remain tensions between the two. Many blogs pick this up and examine what those tensions are, how they hold us back and by what means they might be resolved.

Several of us were inspired by Eric Strain’s editorial which highlighted how we let people down when we leave them with “anything less than flourishing”. The concept and importance of flourishing and wellbeing as goals in treatment, support and recovery was the next most prevalent theme.

The issue of stigmatisation of those with addiction was woven through last year’s blogs but also how this can apply those in recovery and sometimes to those of us working in addiction treatment and support who self-identify as being in recovery. This can lead to voices being dismissed and perspectives being judged harshly and in a damaging way.

Although not a new theme, the big-picture perspective on recovery trajectories and longer-term journeys takes us away from categorising treatment as ineffective, abstinence as unobtainable and helps us to address therapeutic nihilism. Better research on long term outcomes for those with substance problems gives us even more hope for those we work with. This was mentioned many times on our blog pages.

Other key topics included the challenges of finding a meaningful and workable definition of recovery that suits recovery communities, treatment and support providers and academics. Recovery as a concept, arguably held most legitimately and strongly by recovery communities and those in mutual aid groups seems to be getting rebranded in ways that make it less meaningful. It could be it is losing its utility (hence the interest in the concept of flourishing).

Tied into this are the next three themes – whether or not addiction is a disease and why that matters, the often unhelpful blurred line between mild and severe substance use disorders and the value or otherwise of having abstinence as a goal.

The remainder of the topics are pretty evenly represented across the year – threads around hope and despair; the opioid crisis; MAT, residential treatment, evidence for recovery; recovery housing, recovery communities and organisations; lived experience; families and the tension between what individuals and families want vs. what’s on offer.

Quotes

Within 2022’s content are so many inspiring and challenging quotes. Some of these are from us and others are from people we are quoting. I’ve selected just a few that particularly caught my attention below.

Our failure to forcefully advocate that patients need to flourish is tacitly acknowledged through interventions such as low threshold opioid programs, provision of naloxone with no follow up services, and buprenorphine providers who only offer a prescription for the medication.

Eric Strain via Bill Stauffer

It seems to me that basing [the designation of addiction] on public reactions is the tail wagging the dog, and that unstable, conflicting messages probably contribute to pessimism and stigma. If that’s true, the best strategy is to just describe it accurately and focus on other targets for stigma reduction.

Jason Schwartz

Though our treatment systems have yet to fully adapt to healing the whole family, most clinicians understand and even stress the relational component of recovery. Obviously, recovery is not, and cannot be solely about the person overcoming addiction.

Austin Brown

Policy has focused on short-term treatment and harm reduction strategies, critical, lifesaving elements of an effective care system, yet we have seen minimal investment in community-based recovery efforts. If we expanded investment in long term recovery in ways that meet the needs of the recovery community, we could save more lives, strengthen families, and heal communities.

Bill Stauffer

If we want to build community-based services that meet the needs of our recovery community, we have to design funding around what works for these communities

Bill Stauffer

Recovery from opioid addiction is also more than remission, with remission defined as the sustained cessation or deceleration of opioid and other drug use/problems to a subclinical level—no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for opioid dependence or another substance use disorder. Remission is about the subtraction of pathology; recovery is ultimately about the achievement of global (physical, emotional, relational, spiritual) health, social functioning, and quality of life in the community.

William White via Jason Schwarz

The linking of abstinence to moralistic and judgmental attitudes and practices plays into culture war battles that consume too much energy and attention within the field.

Jason Schwartz

It occurs to me there may be a relative match or mismatch between the helper’s notion of what addiction is understood to be, and the purpose of the help as defined by the person seeking help.

Brian Coon

Perhaps the most important insight in recent recovery history is that recovery community, through collaborative effort leads to restoration not only in individual lives but supports healing across entire communities, in all their diversity.

Bill Stauffer

It isn’t mercy. If someone genuinely did not choose to do wrong then compassion for that person isn’t mercy—it’s justice. And conversely, if you can only have compassion on someone if you believe she did not choose her misdeeds, then you’ve defined mercy out of existence. You’re not forgiving—you’re saying there was never anything to forgive.

Eve Tushnet via Jason Schwartz

How easily compassionate and well-intentioned responses to addiction can devolve into something that resembles an addiction hospice. And, when we construct addiction hospices, we shouldn’t be surprised that people die.

Jason Schwartz

Here’s to a rich, thought-provoking, enlightening and inspiring 2023 on Recovery Review.

Continue the discussion: @DocDavidM

Photo Credit: d1sk@istockphoto under license

Why can’t they hear anything I say?

How to overcome the challenges of communicating with a loved one struggling with addiction

Communicating with someone you love is not always easy. Too often, conversations end with disagreements, misunderstandings and even broken relationships. If you are struggling to communicate with a loved one suffering from addiction, here are some helpful guidelines that may get your relationship back on track.

Always start with “I love you”

It’s true that “I love you” is one of the most powerful phrases one can say to another. Although it is not enough to cure a loved one of addiction, letting your loved one know that you are coming from a place of love is the best way to start any tough conversation. It assures them that what you are saying is not meant to cause hurt feelings but must be said because you care deeply about them and their well-being. Make your communication direct, honest and most importantly loving.

Acknowledge that you understand what they are going through

Empathy goes a long way when supporting someone struggling with addiction. They may want to quit, but find it’s not that simple. Many factors are at play when it comes to addiction. They may be on an emotional rollercoaster, working through feelings that range from happiness, anger, loneliness to shame and embarrassment. Your loved one may also be facing old friendships that are not conducive to their recovery, challenging their decision to remain clean and sober. Your loved one wants to know that you understand they are having a difficult time.

Set boundaries

It is healthy for your loved one to know your limits: how far they can go with you and how far you will go with them. Setting boundaries establishes that you are willing to support them in recovery but unwilling to engage in enabling behaviors. Participating in a treatment program for family recovery is a great way to discover your enabling behaviors and learn how to set boundaries for yourself and your loved one.

Make yourself available to listen without judgment

This step has two parts. The first is making yourself available to listen, not just to talk. When relationships are strained due to the erratic behaviors of addiction, it’s easy for both the family members and the addict to become dismissive of one another while telling their side of things. However, it is important to know that your loved one needs you to listen and pay attention to their thoughts and feelings. Part two of this step may be the hardest: listening without judgment. Judgement is when you impose your beliefs and values on someone else. It is an act that can shut down communications immediately with you. Remember, criticizing and judging only make someone hurt more and is counterproductive to helping your loved one.

Understand that addiction is a disease

Educating yourself on the disease of addiction will help you keep the emotional or moral perspective out the conversation. Saying things to your loved one like, “Why don’t you just stop,” or having thoughts such as, “I need to fix this for them,” are removed once you understand that addiction is not a behavior problem, but a medical diagnosis just like heart disease or diabetes. It’s a chronic brain condition that causes compulsive drug and alcohol usage despite the harmful consequences it may cause to the user or others around them. Also, understand addiction needs proper treatment for recovery, just like any chronic disease.

Using these steps can help you hone your communication skills and build a stronger relationship with your loved one in a constructive and supportive way.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The post Overcoming Communication Challenges in Addiction appeared first on Fellowship Hall.

Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health were released this week. Here are a few of the highlights.

Substance Use Disorder Prevalence

46.3 million people aged 12 or older (or 16.5 percent of the population) met the applicable DSM-5 criteria for having a substance use disorder in the past year, including 29.5 million people who were classified as having an alcohol use disorder and 24 million people who were classified as having a drug use disorder.

SAMHSA Announces National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Results Detailing Mental Illness and Substance Use Levels in 2021. (2023, January 4).

That’s a startling number. One of every six Americans over 12 years old has had a substance use disorder in the past year?

Further:

The percentage of people who were classified as having a past year substance use disorder, including alcohol use and/or drug use disorder, was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 compared to youth and adults 26 and older.

SAMHSA Announces National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Results Detailing Mental Illness and Substance Use Levels in 2021. (2023, January 4).

So, the prevalence among young adults is worse than 16.5%?!

I found the relevant table and the past year SUD prevalence for Americans 18 to 25 is 18.5% — nearly one out of five. And that’s just past year. It makes one wonder about the lifetime prevalence.

So, what’s going on here?

Well, one factor is the category of SUD itself. It puts the following 2 people in the same category:

- Megan is a 21-year-old whose social life involves drinking with friends every weekend. When she first started drinking she would get very buzzed with 2 drinks but it now takes 4 drinks. On a couple of occasions, due to feeling tired and hungover, she’s called in sick to work and has skipped several morning classes.

- Mark is a 50-year-old man whose polysubstance use started at age 13. By his late teens, his drinking was causing serious problems and had made several attempts to moderate and quit, but was unable to do so successfully. In his early 20s, his drinking was the cause of several breakups with partners he really cared for and caused considerable strain between him and his family. This caused considerable distress — depression, anxiety, loneliness — and he knew his drinking was making all of it worse, but he was unable to stop or moderate. He became a daily drinker and found that he started to feel shaky if he didn’t have a drink or two in the morning. He was arrested for drunk driving 3 times and had difficulty maintaining employment. His 3rd drunk driving conviction resulted in a jail sentence of several months and an alcohol tether upon release. He snuck drinks from time to time and mostly got away with it, but did end up doing a few short stints in jail for probation violations. Around this time he started to develop a problem with opioid painkillers. This problem grew rapidly and replaced his drinking. Eventually, the cost of the pills made them unsustainable and he switched to heroin. He was unable to maintain housing and employment and would alternate between staying with family and staying in shelters. He’s overdosed multiple times, has acquired hepatitis C, and has tried several forms of treatment including residential, buprenorphine, and methadone. He’s now in a hospital for endocarditis associated with injection drug use.

So, SUDs include people like Megan, with very mild problems that many people “mature out” of without any treatment or intervention, and people like Mark, with chronic, severe, and debilitating addictions.

I believe that Megan and Mark do NOT represent differing severities of the same problem. They represent two different kinds of problems. Influenza and lung cancer are both disorders involving the respiratory system, but placing them in the same category would only create confusion. (I’ve written about the problems with SUDs as a category here.)

This isn’t to say that we should just shrug our shoulders about people like Megan, but it does help explain those eye-popping numbers.

Another headscratcher is the increase in the NSDUH’s prevalence estimates over the years. In 2014 they estimated that 8.1% of Americans 12 and older met criteria for a Substance Use Disorder (pg 23).

Recovery Prevalence

The finding that’s getting more attention is about the prevalence of recovery.

Before we look at that number, it’s worth considering what we might mean by recovery.

- Recovery from what? Traditionally “recovery” has been associated with addiction, but not with less severe and acute substance problems. The NSDUH does not make this distinction and, therefore, with cultural understandings of the term.

- Is recovery an identity adopted by survivors of a life-threatening illness that causes serious impairment in multiple life domains and signals connection to a community of others who share the identity?

- Does recovery indicate a way of life that involves healing from serious illness, repairing damage in multiple life domains, restoration of self in personal, familial, and community roles, and a process of becoming “better than well” (something akin to post-traumatic growth)?

- Does it refer to remission, or the reduction of symptoms to subclinical levels? (If so, why use the term recovery rather than remission?)

- Does it describe a clinical endpoint for an illness/disorder?

The report indicates that 7 in 10 (72.2 percent or 20.9 million) adults who ever had a substance use problem considered themselves to be recovering or in recovery.

Again, a stunning number. BUT, it’s worth reflecting on the meaning the key terms — “substance use problem” and “recovering/recovery.”

So, how does the study operationalize these terms? Here are the relevant questions from the survey.

Above, we discussed the problems with SUDs as a category. This question lowers the threshold for inclusion even further. Anyone who does not meet criteria for an SUD but thinks they once had a problem would be included. If the SUD diagnostic criteria are based on beliefs about what constitutes clinical significance, this question includes subclinical levels of use.

The question about recovery is also framed in a way that makes it hard to answer any way other than “yes, I am recovering or in recovery” unless the person is in the throes of a substance use problem.

Megan would answer yes. If Mark were to find his way to recovery and successfully rebuild his life with the help of a community of recovery, would it make sense to put him and Megan in the same category? Where might that be helpful? Where might that be misleading? If recovery is understood as an endpoint and Megan is using alcohol in moderation, could considering moderate alcohol use “recovery” constitute at dangerous goal for someone like Mark?

Imagine the questions asked about disorders affecting the respiratory system. Andrew responds “yes”, that he’s had bronchitis before. Angela responds “yes”, that she’s had lung cancer. For the question about recovery, of course Andrew says “yes” that he has recovered. Angela responds “yes”, that she went through chemo and had a lung removed.

Is Andrew likely to think of himself as “in recovery” or “recovering”? Probably not, but the only sensible answer to the question is “yes”. What do they share in common?

Imagine the question was about weight problems. Bill says yes because his BMI once put him in the overweight category and he shed 15 pounds. Robert says yes because he once weighed 450 pounds and has lost 250 pounds. If we put them together because we assume they share a common experience and identity, how is that likely to go?

It’s important to note that this use of the term recovery is considerably different from its cultural, medical, or research use.

Making sense of all this

So… what should we make of all this?

None of this is to suggest that this information is useless. It could be very helpful for understanding patterns of substance use and conceptualizing public health needs and interventions.

However, I’d urge caution about trying to infer much about the prevalence of serious substance problems and the prevalence of what our culture has understood as recovery.

I also wonder about the effects of this federal survey’s drift (a doubling of SUD prevalence over 7 years?) and repetition of its reconceptualization of “recovery.” How does that change cultural, professional, and personal concepts? Where might that be helpful and unhelpful? What discord does that create? When and where is it desirable and undesirable to create discord? When this kind of work stirs discord between communities, professionals, advocates, and researchers, how should that be navigated? Who decides?

I don’t know, but it’s worth discussing.

Gee Matamoros’ journey to recovery included some very dark passages. Now he travels a brighter road, and insists on enjoying life as much as possible. Fortunately for us, one of the things he enjoys most is spreading the word about SMART.

In this podcast, Gee talks about:

- How his substance misuse and poor choices landed him in a psychiatric ward

- Why his life was everything to the extreme

- Walking the tight rope of his identity and doing what he was told

- Using substances to cover and sooth impactful moments in his life

- Always running from his authentic self because it wasn’t acceptable

- Finding SMART in rehab, where he could explore other pathways to aid in his recovery

- Sleeping like a baby because of the changes he’s made in life

- How the COVID pandemic helped launch and grow the online Spanish meetings

- What he’s doing now to advocate for SMART and the Latinx community

- Recovery being a community effort – there is support everywhere

Additional resources:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

PLEASE NOTE BEFORE YOU COMMENT:

SMART Recovery welcomes comments on our blog posts—we enjoy hearing from you! In the interest of maintaining a respectful and safe community atmosphere, we ask that you adhere to the following guidelines when making or responding to others’ comments, regardless of your point of view. Thank you.

- Be kind in tone and intent.

- Be respectful in how you respond to opinions that are different than your own.

- Be brief and limit your comment to a maximum of 500 words.

- Be careful not to mention specific drug names.

- Be succinct in your descriptions, graphic details are not necessary.

- Be focused on the content of the blog post itself.

If you are interested in addiction recovery support, we encourage you to visit the SMART Recovery website.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

If you or someone you love is in great distress and considering self-harm, please call 911 for immediate help, or reach out to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline @ 988, https://988lifeline.org/

We look forward to you joining the conversation!

*SMART Recovery reserves the right to not publish comments we consider outside our guidelines.*

Submit a Comment

Recovery journeys are dynamic, take time and for those who receive treatment, may need several episodes. For some, residential rehab is part of the journey, just as harm reduction interventions can also be part of the journey. However, residential rehabilitation is a complex intervention and complex interventions are difficult to study.

In Scotland, the government is making rehab easier to access and growing the number of beds. This development is not without its critics. Some feel the resource needs to ‘follow the evidence’ – in other words into harm reduction and MAT interventions. This all-the-eggs-in-one-basket position would reinforce the rigid barriers that make rehab the domain of the wealthy or the lucky.

‘Follow the evidence’ in this context is a refrain that implies that there is no evidence that rehab works to help people achieve their goals and improve their quality of life. That is simply not true. Last month saw the publication of a literature review on residential rehab by Scottish Government researchers. It’s a thorough piece of work. This summary of the research evidence provides verification that “that residential rehabilitation is associated with improvements across a variety of outcomes relating to substance use, health and quality of life”.

Rehab is linked to improvements in mental health, offending, social engagement, employment, reduction in substance use and abstinence. There is little research that compares rehab with other treatments delivered in the community, but where there is, the evidence suggests that “residential treatment produces more positive outcomes in relation to substance use than other treatment modalities.” The review also suggests that rehab can be more cost-effective over time than other treatments.

The report also highlights problems and gaps in the evidence base. What happens within the walls of rehabs is diverse and the models and delivery vary, so when we talk of rehab we are not talking about something uniform. We need to gain an understanding about the most effective interventions. Research suggests, for instance, that integrating mental health care into rehab treatment is associated with better outcomes.

The Scottish Government’s literature review highlights gaps that need to be plugged. I think it’s fair to say that there are no queues of Scottish academics curling round the block – researchers chomping at the bit to get their teeth into studies on the place of rehab in treatment and recovery. That we have unanswered questions is not a surprise. Further, it’s important for us to face up to the fact that rehab is not necessarily without risks to individuals, particularly for those with opioid dependence. Those need to be faced square on.

In terms of research, residential rehab, mutual aid, lived experience recovery organisations (LEROs) and community recovery programmes have been largely neglected.

Indeed, the perception of such risks may be one of the main reasons for resistance to rehab as an intervention. We don’t know if those going to rehab in Scotland have higher mortality than in other kinds of treatment, but there is evidence from elsewhere that this could be the case. However, it is plausible that people with higher problem severity (and higher risk of death as a result) end up in rehab. The mortality rate in intensive care units is higher than in general wards, but we don’t stop people going to intensive care because of that.

We also need to be aware that there are mitigations that can be employed to reduce risks. These may include things like comprehensive aftercare, re-titration of those who want to leave treatment early and rapid re-entry into prescribing services if individuals return to use.

Recovery housing, take-home naloxone, overdose prevention, assertive referral into recovery community resources, outreach and recovery check-ups may also reduce risks. Standards could be developed to encourage the adoption of such practices. The impact of these have not been tested in research, but they could be.

I don’t believe it is in the interests of those individuals (and their families) who struggle with dependence on substances for us to maintain treatment turf wars. We can have harm reduction and recovery. We can have MAT and abstinence. We can have outpatient treatment and residential rehab. Whatever we have, it needs to be plugged into supports across housing, criminal justice, benefits, education, training and employability and health. A joined-up, comprehensive treatment system with strong links between its component parts will serve individuals best.

We don’t need to say one thing is better than another, but we do need choice and through shared decision making we can try to help patients align themselves to a treatment option that helps them meet their goals. And we need to be humble too. Evidence suggests that over a lifetime, most people resolve their problematic use of substances. When they look back, they may be grateful for the part that treatment played in their recovery, but it is likely that it will be only one of many factors that helped.

For the moment though, we can certainly challenge the voices that say ‘there’s no evidence that rehab works’, for there is ample evidence that it does. I’m not unrealistic about this though. As I’ve been writing, I have been mulling over the wisdom of Ahmed Kathrada’s observation: ‘the hardest thing to open is a closed mind’. That shouldn’t stop us trying.

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

I watched an informational video about search patterns used by the Coast Guard and gained some thoughts I decided to share. The video was just under 30 minutes long and you can find it right here if you’re interested.

As you read this article, see what you notice from outside our field that could serve as hints to help improve our clinical work as addiction professionals.

What are we looking for and where is it heading?

The video I watched showed how Coast Guard search and rescue teams vary their search patterns and their use of search assets (ships, planes) according to:

- the type of object they are looking for;

- the size of object;

- the height and amount of visible surface area of the object above the surface of the sea;

- and “drift”.

As an example, they noted a person wearing a life jacket will float differently from a disabled flat-bottom boat.

Interestingly, they said that drift of the object will vary according to the total of the ocean current at the surface, the deeper current, and the wind. And they clarified that the different currents and wind might each be flowing in the same direction, or different directions.

To me all of that was fascinating and I started to consider possible areas of application for our work. Among other things, I asked myself things like: “As addiction professionals, what is it we are looking for and why? And where is the patient heading?”

Is our work complicated enough? Are we letting science help us?

The search crew stated that all the relevant data about the different currents and the wind are put into a computer. And the software then generates a tailored search pattern for that specific scenario. And the pattern is given to the air assets, ships, and personnel conducting the search.

- They stressed that different things float differently, and the atmospheric and ocean currents and conditions also differ.

- And they stressed the fact that all the relevant Coast Guard staff experience standardized training, so they will all understand the same things and follow the same procedures.

Again, I started to think about our work. Among other things, I wondered if we have made our work complicated enough, and if we as a field are really letting science help us like we could.

Best-practice, structured methodology? That also champions the patient?

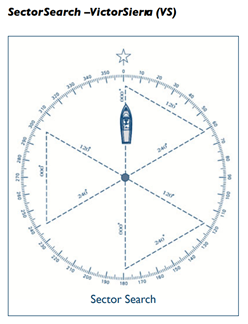

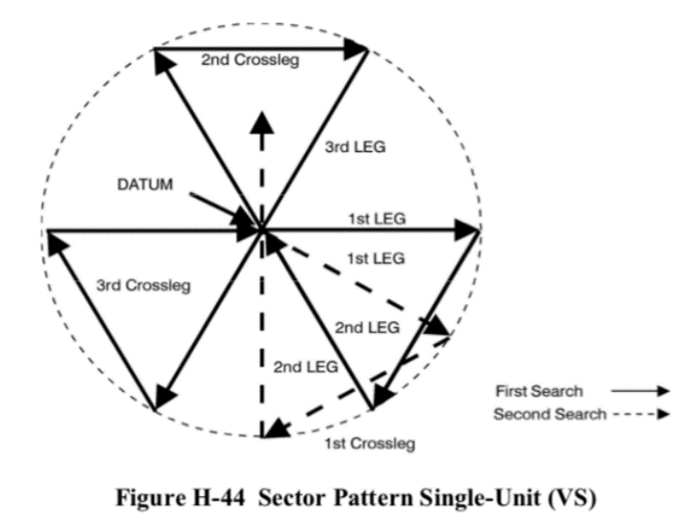

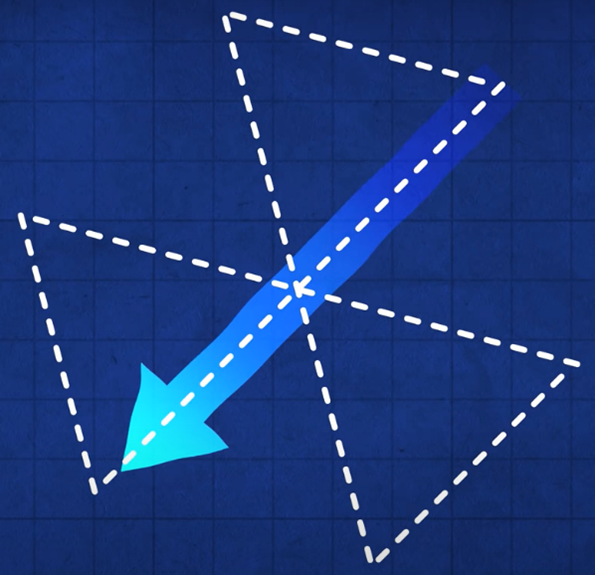

In the video, the “Victor Sierra” search pattern was featured.

The Victor Sierra search strategy is used to look for a small object in a relatively small location where the probability of the object being within that location is relatively high. The pattern is built from 3 isosceles triangles. It was initially odd to me, but rather interesting.

https://ccga-pacific.org/files/library/Chapter_9_Search.pdf. Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

During the use of the Victor Sierra search pattern, one of the crew is assigned to look out the left side of the vessel, one the right side, and one out the front – visually covering the entire search area in a thorough and reliable way.

But before the search begins the direction that the object is moving in is determined. And the direction is determined from the combination of the wind and both shallow and deeper currents.

That combination is used to understand the movement of the object being searched for, and also for a buoy they call the “datum”. The datum is placed in the water and left free to float and move on its own according to the wind and currents – just like the object being searched for.

The word “datum” is fascinating to me because it indicates a single reference point. The presenter noted that in engineering “datum” is the reference point from which one measures other things.

http://wow.uscgaux.info/Uploads_wowII/070/SEARCH_and_RESCUE-A_Guide_for_Coxswains_May_2020.pdf Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

But in this case the datum is literally a moving thing, not a fixed or stationery thing. And its motion (direction and speed) are the sum of the wind, shallow current, and deep current.

They went on to say that the search vessel’s initial motion is always in literal line with the movement of the datum.

Accessed from the world wide web on 01/22/2022

Interestingly, once the datum is deployed in the water, the ship backs away from it – in order to not effect it or its movement. The angles of the search pattern are then followed at a fixed rate of speed, at a set distance for each, and completed in a certain order.

As I watched the video, I saw many metaphors related to our work. And I asked myself many questions. For example, “Do we have a nationally-normed, universally applicable, best-practice structured methodology to guide us? One that champions the patient as the center?”

How person-centered are we?

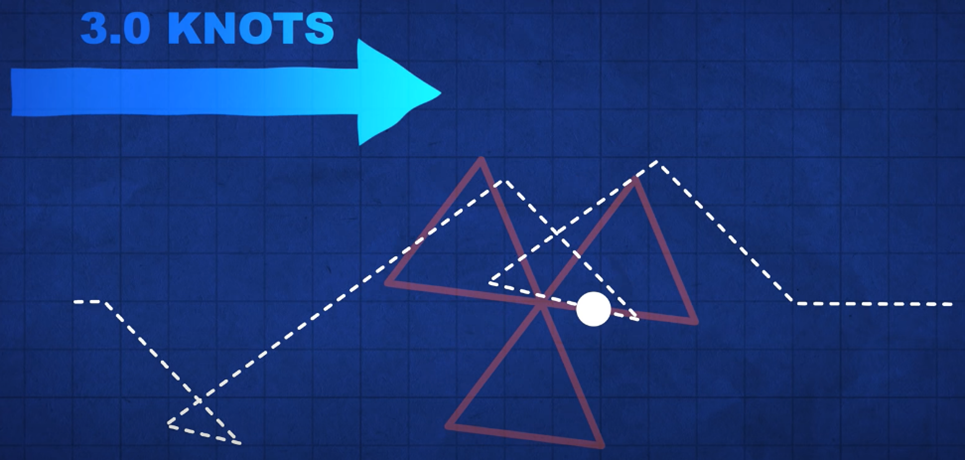

Interestingly, the order in which the segments of the search are completed is static, but that order does not complete one full triangle at a time.

How is the search pattern followed?

- The first leg of the search starts from the location of the datum and is in the direction of the wind/water as crew can best determine.

- Once that first leg of the search is completed, the next angle is calculated from the location of the end of the first leg.

- Following the completion of this second leg, the ship heads directly back to the datum, and this is not done on a preset or calculated heading. Rather, the crew visually locates the datum and drives straight to it.

- Once they physically reach the datum, the direction/degree/angle of the next leg of the search is then determined.

As the search proceeds in this way, the search pattern is kept integrous by repeatedly returning to the datum, rather than making successive calculations from calculated locations. And in this way each new search angle moves with the natural combined movement of the wind and water.

I personally found the level of structured methodology and intentional freedom in the planned work they describe greatly inspiring.

And I asked myself if it is realistic to anticipate in the future:

- a universally available set of best-practice structured methodologies;

- that champion the patient;

- created for us on a normed basis;

- and specifically tailored to the particulars of the current person and their situation.

I ask myself if we are willing to be guided in the most expert way possible?

Messy inconsistency or a combination of expertise and natural forces?

Given drift, the lines that are ultimately searched do not form triangles. This is because the search lines move in time, congruent with the buoy.

By contrast, if the buoy did not move, the course of the search craft would simply replicate the pre-set triangular pattern. But it never does. The actual final shape of the search pattern is non-intuitive and always reflects the actual current/wind.

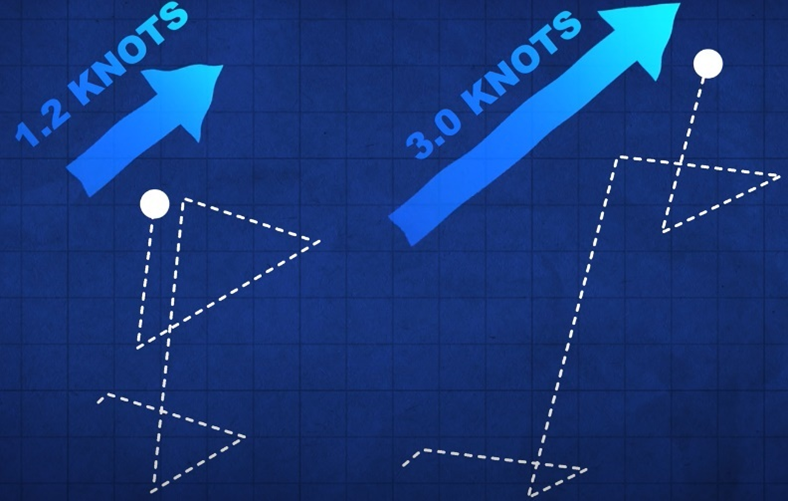

The shape of the search pattern will differ with the rate of the drift. The search moves with the current.

- For me, the wind is the manifest content of the life of the patient.

- And the water current is the latent content of the life of the patient on both shallower (more accessible) and deeper (less accessible) levels.

- And for me, the buoy reminds me of the person we are searching to help – who is always moving and provides us our center of reference.

This portion of the video made me wonder if we should consider a return to that center each time we complete our immediate purpose, and before we chart our next clinical move.

And it made me think about how our work appears from the outside. For example, does such work reflect messy inconsistency when viewed from the outside? Or does our work trace the combination of expertise and natural forces when viewed from the inside?

Appreciating drift, rescue, and what comes after rescue

The Coast Guard staff informed the film maker that wind and water are often aligned differently or may even be in opposition. They noted that these may all differ from each other due to the differing forces that produce each of them separately. To me, that fact alone is interesting and informs our work.

And they added that the most important task is the first task – determining the “set” and “drift” of the buoy. They stated that “set” refers to the direction of the buoy and “drift” refers to the speed of the buoy.

Once the starting center point of the pattern is established, the direction for the first leg of the 3 triangles is determined by going with the elements, not against them. They also stated that once the speed of the craft is set, it is not changed. Rather they, “Let the current take us.”

- To me this shows us the value of person-centered methods.

And to me this illumines areas of possible struggle for professional workers in our field. For example, do we choose:

- the datum (strictly person-centered reality) as our only reference point;

- the lighthouse that we might need to move toward once the rescue has been accomplished as our reference point; or

- the north star of long-term improvement as our reference point?

Which reference location do we use in the current moment? Or should we combine reference locations? Or at times oscillate between them?

For our work, would we only and always choose the location of the datum as the imagined destination of “full recovery 5 years after the last clinical touch”? Or should we always and only place it and leave it at the epicenter of the person served?

Or could the location of the datum be different, at different times, for different or changing purposes?

- If the epicenter of our work is the person served, then the patient is the reference point.

- If the epicenter is an imagined and much-fuller quality of life, is our effort meaningfully sufficient using that and only that long distance improvement as our only reference?

- But even then, who should define the hoped-for final location, and when, and on what terms?

And speaking of location, what about wind, shallow currents, and deep currents – at the location of the patient’s home or newer waters once they arrive safe? Are we also building safe-harbor locations in our society and larger communities? Do we appreciate all three of: drift, rescue, and what comes after rescue?

Science and compassion?

To conclude I’ll say that I imagine clinical work that includes:

- inputs from the patient, family members, clinical workers, and research scientists;

- reference points including the current condition of the person we serve contextualized by environmental conditions as they are;

- incremental markers to a safe harbor; and

- much farther true-north type wellness goals.

And I imagine our work both moving toward, and rotating on or pivoting against, pairs or groups of these markers (rather than only using one passive reference point) in best-practice algorithms, as we proceed.

Bob Lynn has summarized his aim for our work as “science and compassion”.

Hopefully this article has presented a framework and some considerations inspiring addiction professionals toward that aim.

Suggested Reading

Behavioral Health Recovery Management: A Statement of Principles.

Hofmann, S. G. & Hayes, S. C. (2018). The Future of Intervention Science: Process-Based Therapy. Clinical Psychological Science. 7(1): 37-50. doi.org/10.1177/2167702618772296

Proctor, S.L, Llorca, G.M., Perez, P.K. & Hoffmann, N.G. (2016). Associations Between Craving, Trauma, and the DARNU Scale: Dissatisfied, anxious, restless, nervous, and uncomfortable. Journal of Substance Use. DOI:10.1080/14659891.2016.1246621