The conclusion of the two-parter. Part one is here. Professor Selman’s last five essentials:

6. Different therapies appear to produce similar treatment outcomes. Project MATCH, a huge psychotherapy trial showed similar outcomes for the techniques of motivational enhancement therapy, twelve step facilitation and cognitive behavioural therapy. Other trials including British ones have shown the same results. The key thing for me is always around the quality of the therapeutic relationship and what represents best value for money. One more thing; there’s been an important addition to the evidence base since this which changes things. Find it here.

7. “Come back when you are motivated” is no longer an acceptable therapeutic response. The old idea that you need to reach rock bottom before change is possible has been challenged (most clearly by Bill Miller). In a recovery oriented treatment service the workers take on some of the responsibility for helping to generate hope and motivation. In a therapeutic community, the other community members do this very effectively. Motivational interviewing is a useful tool and the importance of the quality of the client/professional alliance is stressed. The old response to blame the client when treatment fails just doesn’t do it any more: we need to hold ourselves to account too.

8. The more individualised and broad based the treatment a person with addiction receives, the better the outcome. The professional and the client developing a care plan together focussing on meeting needs and reaching goals is the ideal. There is plenty of evidence that this makes a difference. If this focusses on building recovery capital across a range of domains, clients are likely to do better. Do enough people in addiction treatment understand the key components of building recovery capital?

9. Epiphanies are hard to manufacture. One way of defining an epiphany is that it is a sudden intuitive realisation of the truth of something. One of the fascinating things about working in the field of addiction, writes the prof, is coming across people who have had dramatic and sudden life changing recovery experiences. Bill Wilson, the co-founder of AA was one example. Part of the process is overcoming self deception. Hearing others’ stories of recovery experiences is probably important here and, of course, this takes place in mutual aid groups.

10. Change takes time. Who could argue? He gives a rather neuro-scientific description of this, but wins me over in the end when he points out (from the viewpoint of a medic of course) that clinical management gives way to personal management as people move through the stages of treatment; rehabilitation; aftercare and self-management. Of course this is not the route of all to recovery, but it does reflect collective experience to some degree.

And if these are the ten most important things about addiction, then what are the ten most important things known about recovery? I think the language and tone of addiction treatment has changed to focus more on the positives that accrue with recovery than the negatives that are removed or diminished by traditional treatment approaches. This is a good thing, but it’s clear the scientific study of recovery lags well behind the scientific study of addiction. Let’s do some catching up!

Sellman, D. (2010). The 10 most important things known about addiction Addiction, 105 (1), 6-13 DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02673.x

This is a version of a blog I published a few years ago, but thought it still relevant today.

Doug Sellman is a professor of psychiatry and addiction medicine in New Zealand. In 2010 in the journal Addiction, he attempted the difficult task of distilling the ten things you need to know about addiction from the research of the last thirty years. No mean feat.

Well, what are they?

1. Addiction is fundamentally about compulsive behaviour. In normal behaviours, the control in our brains is top down. In addiction the cortex (the decision making bit of the brain) becomes ‘eroded’ to a ‘dehumanised’ compulsion. Sellman outlines the well-studied brain circuits involved, and points out how this view creates one of the defining marks of addiction: continuing to use despite negative consequences.

2. Compulsive drug seeking starts outside conscious thought. The debate about free will (and as the prof says ‘free won’t’) gets complicated here. Apparently the conscious part of our brain is about a half second behind imprinted learned behaviours. The lag and its effects are exaggerated in addiction and well learned patterns including cues call the shots over the ‘higher’ brain’s ability to avoid damaging choices. Result: illogical self-harming behaviours continue.

3. Addiction is about 50% inherited, but it’s much more complicated. Genetic and population studies show a strong genetic element for addiction with some folk being more vulnerable than others. It gets complicated because it’s not just about a single gene or even a few, but possibly hundreds, and even then they interact with infinite variations in environment. This is not about ‘nature versus nurture’, but represents a ‘new interactive model of nature via nurture’.

4. Most people with addictions who come for help have other psychiatric problems as well. For those wanting to move away from the medically dominated model of treatment, this is a big obstacle. 75-90% of those asking for help from services have diagnosable mental health problems including depression, social phobia and post traumatic stress disorder. Alarmingly though, many of our big treatment studies have excluded people suffering from mental health problems. For those of us involved in providing help for those wanting to recover, we will need to ensure that mental health needs are not overlooked. On a personal note though: I do hold a hopefully healthy observation that many of the psychiatric labels we pick up as active addicts melt away in recovery without the need for psychiatric treatment.

5. Addiction is a chronic relapsing disorder in the majority. This was the most challenging of the ten findings for me to simply accept. Prof Sellman says that fewer than 10% of those going through treatment will experience continuous long-term abstinent recovery. He does point out that life will be better for many after treatment and that we need to accept relapse as part of the deal for many. Not doing so will prevent folk coming back for help. There is a tension in this for me between instilling hope and optimism and being unrealistically positive. Other research gives more hope for longer term outcomes suggesting more than half will achieve remission.

Coming soon: Part 2

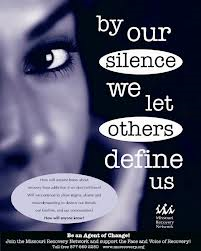

The first blog in this series explored the value and limitations of recovery storytelling as an anti-stigma strategy. We suggested that public storytelling is best wedded to larger recovery community inclusive strategies that move beyond the goal of changing personal attitudes to the larger goal of dismantling the institutional machinery that perpetuates stigma and discrimination. Today, we explore the risks inherent within public recovery storytelling.

Public Recovery Storytelling: Spectrum of Risks

Individuals, family members, organizations, and the recovery advocacy movement reap benefits from public recovery storytelling, but these same parties are also at risk for injury as an inadvertent outcome of such public storytelling.

Individuals and family members may experience the therapeutic effects of their advocacy activities, but there are also accompanying risks of personal embarrassment or humiliation, exposure to acts of social shunning or discrimination, and, at worst, destabilization of personal and family recovery. Moving recovery from the private to public arena entails navigating these risks.

Youth and other individuals at early stages of recovery may be particularly vulnerable for such injuries. The media story of recovery is most often told from the perspective of the recovery initiate rather than from the perspective of long-term recovery. We best represent the story of recovery when we speak from panels representing diverse pathways, styles, and stages of addiction recovery. Young people and others in early recovery possess heightened vulnerability and should be carefully screened for public recovery advocacy activities. They should be oriented to the benefits and risks of public recovery disclosure via an informed consent process and given structure and support when involved in public recovery advocacy. If a person experiences a recurrence of AOD use and related problems who has earlier served as public recovery advocate, their prior experience as a visible recovery advocate can pose a significant obstacle (via shame, resentment, etc.) to recovery restabilization.

There is a zone of service and connection to community within advocacy work, and we must do a regular gut check to make sure we remain within that zone and not drift into advocacy as an assertion of ego. The intensity of camera lights, the proffered microphone, and seeing our published words and images can be as intoxicating and destructive as any drug if we allow ourselves to be seduced by them. If we shift our focus from the power of the message to our power as a messenger, we risk, like Icarus of myth, flying towards the sun and our own self-destruction. To avoid that, we have to speak as a community of recovering people and avoid becoming recovery celebrities—even on the smallest of stages. (White, 2013)

The decision to pursue public recovery advocacy is best made in consideration of family and loved ones. While the zealous new recovery initiate may feel called to this public storytelling role, they must consider the potential effects of public disclosure on family members and loved ones. After considering such effects, some advocates have postponed their roles as public speakers until their children are at an age that minimizes any potentially negative effects upon them. Those involved in public recovery storytelling have found it helpful to orient family members and loved ones on the content of the story, the venues in which it will be shared, and how to best respond to questions that may arise from its presentation.

The reputations of organizations sponsoring public recovery storytelling and the larger recovery advocacy movement can be injured when speakers are not provided support, guidance, and vetting by the community for suitability and readiness for public recovery story sharing. This is particularly true in the case of the perceived “fall from grace” of a visible recovery advocate. In such circumstances, individuals and families suffering from addiction may be less hopeful and less likely to seek help because of such damaged reputations, and policymakers may be less amenable to supporting recovery advocacy organizations.

Recovery Storytelling: The Risk of Conflicting Agendas

Information related to addiction and recovery is disseminated through a wide variety of public venues: television, film, newspapers, magazines, the Internet, and through a broad spectrum of public and professional meetings. Representatives from these venues often approach recovery advocates for interviews or presentations related to their recovery experiences. Such opportunities are a means of carrying a message of hope to those affected by alcohol and other drug problems and a platform for advocating pro-recovery social policies and programs.

In spite of the potential benefits of public recovery storytelling, public recovery disclosure as we have noted can pose risks to multiple parties. A starting point for risk management related to public recovery story-sharing is the recognition that the interests of the multiple parties involved in such events may be congruent or in conflict.

Requests for interviews or presentations often come with hidden agendas—planned narratives that meet the interests of those doing the inviting. Those inviting our stories may distort them to support agendas and talking points incongruent with the goals of recovery advocacy.

For example, distorted media coverage of active addiction fuels social stigma and contributes to the discrimination that many people in recovery face as they enter the recovery process. When media representatives interview people in recovery, they often want the most dramatic, traumatic, and sensationalist details related to one’s addiction but seek or report few details on the actual processes of recovery or the regenerative and transformative effects of long-term personal and family recovery.

It is said that if you are not at the table, you are on the menu. This has never been any truer than with the use of our stories. We must have pointed dialogue about how our narratives are used while having meaningful discussions across our diverse community on the messages we are trying to convey. These discussions must include how our stories can have unintended consequences and we must work together to ensure that our stories serve our common interests and our shared vision of an inclusive world free from stigma and discrimination.

This is all a way of saying there is much to consider in the decision to share our story, our decisions on how that story can be best presented to different audiences, and how we can best protect ourselves and other parties through this process.

Link to Bill White Post HERE

Coming Next: The Pillars of Stigma and Recovery Storytelling

Reflecting back this morning of some very early lessons in my recovery journey and what I have grown to understand about the power of gratitude. Full disclosure here – I am not inherently a positive person. My inner voice can be quite negative with great frequency and intensity. Negative thinking, lists of things that have gone wrong and projected catastrophic future events play out without effort and multiply when I focus there even for a moment. I call this my Eeyore brain; it can hijack my day when my eyes first flutter open. Nothing is good, everything will sour, woe is me. This is the inner Eeyore whom I can ill afford to entertain.

Negativity was a dominant thinking pattern in my early life. Addiction started in my early teens and my use spun out of control before age 20. It was recovery or die for me and sought help in the middle of my 21st year on earth. It is quite ironic that the year it was legal for me to use one of my drugs of choices (alcohol) was the year I ended up getting into recovery. Eeyore ruled my brain and that negative inner voice told me with all certainty that my life was over, bridges burned could not be rebuilt, the trajectory was all downhill with no social life and the substances that helped quell the pain now off limits.

This was all of course, untrue. Wise people I had the great fortune to meet early in recovery suggested I look deeper for things that I could be grateful for. I made gratitude lists in my head, sometimes hourly to get through the long minutes. The minutes added up and my gratitude list lengthened. I learned that the inner Eeyore was not my friend nor an accurate inner soothsayer of what lay ahead. The deep truth is without learning how to be grateful early on, I am quite confident I would not have made it to 30 and yet, here I am a formerly young person still in recovery at 55. The power of gratitude.

Shifting a few decades forward, truth be told, 2020 has been by far the most challenging year of my recovery since that very first one in 1986. Challenges have come from all directions, personal, professional, from the pandemic and other societal disruptions playing out across our world. I have found that social media can be a tool to develop gratitude and connection and also unfortunetly an amplifier of my inner Eeyore if I allow it. I have had to dig deep, reflect longer and focus on gratitude and things that help restore me. I suspect I am not alone and many readers also have experienced these dynamics. Many of us in recovery are struggling, yet we also have some powerful tools we picked up along the way.

We know a bit about gratitude. Science and philosophy reflect on the value of gratitude. As noted in this article from Harvard Health Publications, “gratitude is strongly and consistently associated with greater happiness. Gratitude helps people feel more positive emotions, relish good experiences, improve their health, deal with adversity, and build strong relationships.” According to this paper published in 2004 by the Oxford Press, positive-emotion-focused techniques help individuals create an internal environment that is conducive to both physical and emotional regeneration, including physiological aspects such as heart health and digestion. The practice of gratitude is present from the very earliest 12 step fellowship writings, and in most world religions. It is reflected in the writings of Western Philosophy such as that of Epictetus who said “He is a wise man who does not grieve for the things which he has not, but rejoices for those which he has.” Eastern Philosophy also reflects gratitude including Confucius who said “It is better to light one small candle of gratitude than to curse the darkness.” Let’s light our candles now.

So this is my meandering Thanksgiving day blog post. I am grateful to be here, now. Life experience tells me that I am a poor forecaster of negative future events and I consistently underestimate my own resiliency and some of the positive elements operating in the world around me. No sugarcoating here, the world is indeed a mess, yet it is so very much more than that if we dig a little deeper. Thanks be to my mentors and for all those who have crossed so far in my path on this earth. I am grateful for you who have read this far. I add you the reader to my Thanksgiving Day 2020 gratitude list. May you find the kernels of positivity in the field you stand in and sow them to find inner abundance and bounty.

I sincerely hope that you have a long gratitude list this Thanksgiving Day, especially if you battle with the inner Eeyore as well.

Bill Stauffer

President’s Message to the SMART Recovery Community

I bring greetings to our entire community and a special welcome to seven new SMART Recovery USA board members, bringing our total to seventeen. Not since SMART was founded more than a quarter-century ago have we assembled a more talented and dedicated group of people to help lead our organization. They have the diverse skills and vision we need to innovate our services and extend SMART’s reach to every individual and family who needs our help.

The need for SMART Recovery has never been greater as the COVID pandemic has made an already daunting addiction epidemic even worse. Our community will meet these challenges more quickly and more effectively with this infusion of new leadership.

We are fortunate to have Joe Gerstein and Tom Horvath from our original board, along with long-time member and Vice President Brett Saarela, who knows addiction as a peer and a highly regarded professional counselor, and Elaine Appel, a 16-year member with nonprofit expertise. They helped build and sustain this organization for more than a quarter-century and provide us with continuity as we address the critical challenges ahead.

As this year draws to a close, I’d like to share brief thoughts about the latest science that supports us, SMART leadership, our pending two year strategic plan, and how we can create our future together.

The Science Supporting SMART’s Efficacy

A growing body of scientific research supports the efficacy of SMART. Two major longitudinal studies underway funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) should increase our evidence basis:

- Expanding the Science on Recovery Mutual Aid for Alcohol Use Disorder: An Investigation of SMART Recovery by John F. Kelly, Ph.D., ABPP, Elizabeth R. Spallin Professor of Psychiatry in the Field of Addiction Medicine at Harvard Medical School, the Founder and Director of the Recovery Research Institute.

- A third study in the Peer Alternatives (PAL) series comparing AA, LifeRing, SMART Recovery, and Women for Sobriety by the Alcohol Research Group, led by Sarah E. Zemore, Ph.D., senior scientist and associate director of the group’s National Alcohol Research Center.

The first two PAL studies found, among other things, that the four recovery support models are equally effective. In 2019, SMART Recovery USA honored Zemore as the inaugural recipient of the SMART Science Award.

To promote worldwide collaboration on such research, SMART Recovery International recently formed the Global Research Network. Kelly and Zemore serve on the SRI Global Research Advisory Committee, which oversees the network. The committee is chaired by Peter Kelly, Ph.D., associate professor and deputy head of research at the School of Psychology at the University of Wollongong, Australia, and a member of the Australian College of Clinical Psychologists.

Leadership to Support a Growing Organization

The first SMART Recovery board was composed almost entirely of professionals, including medical practitioners, addiction psychiatrists, psychologists, and scientists. Over time, we have evolved to the point that peers occupy most of the board seats, including all the officer positions. I suppose one could say today that “the inmates are running the asylum.”

However, the fact is that diverse skills and perspectives are critical to lead a growing nonprofit. These include essential business or entrepreneurial skills, financial and risk management, education and training, marketing and communications, information technology, fundraising, government relations. The new board members give us more racial, age, and gender diversity. Also, all of them have contributed to our new long-range strategic plan.

The Two-Year Strategic Plan

We started this strategic planning process late last year. We have benefited a great deal from guidance by a team of expert consultants associated with the SAMHSA initiative known as Bringing Recovery Supports to Scale: Technical Assistance Center Strategy (BRSS TACS). This initiative has a long history of helping groups in the recovery field. For example, they have provided significant support to Faces & Voices of Recovery. In fact, Patty McCarthy, FAVOR executive director, served as deputy director, the position that our lead BRSS TACS consultant, Valerie Gold, holds. They put a great deal of work into this undertaking and wrote it up as a model of their best work.

In this planning process, we have made an in-depth, comprehensive, and honest assessment of the state of SMART USA. We have tried hard to recognize the elephants in the room—averting a common mistake that dilutes and undermines strategic planning. It is a telling sign of our maturity that AA is not among the elephants—except perhaps the need to stop thinking of ourselves as an “alternative.” To slay the elephants, we must:

- Increase diversity in our community, especially people of color, youths, and women.

- Better support, train, honor, and celebrate our volunteers.

- Cultivate more, larger, and sustainable funding streams.

- Undertake aggressive and ongoing marketing and communications programs that target professionals, the broader medical community, and the general public.

The next step is to execute the plan. This will not be easy, but SMART has endowed us with the skills and orientation required. We are empowered, resilient, and open to many solutions. We have boundless passion, energy, and commitment to our cause.

We need to nourish trust, mutual respect, a team orientation, and corresponding values that produce the gestalt effect where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. We need this for our staff, our board, and our volunteers. Overwhelmed by the fast pace of growth over the past ten years, we must rebuild our culture. We all need more life balance, relief from compassion fatigue, and a sense that our work is valued, that we are making a difference in the mission that SMART pursues.

Creating Our Future

The best way to predict your future is to create it.

That famous line is often attributed, incorrectly it turns out, to Abraham Lincoln. Whoever created it had a self-empowered mindset. Management guru Peter Drucker used it in strategic planning courses for aspiring business leaders. He contrasts two people on a river, one floating on a raft who drifts aimlessly wherever the current takes him with the other in a kayak who navigates his way toward a desired destination. The kayaker is not entirely creating his future, but he exerts much control, adjusting the speed and the course while avoiding obstacles.

Our effort to execute this strategic plan might be more analogous to white-water rafting in which we’re together in the same craft. Anyone who’s had this adventure knows the peril of careening through roiling waters around massive boulders that can upend the raft and toss everyone overboard. Staying dry requires a highly coordinated team effort. For example, to avoid collisions with a boulder, everyone must paddle furiously in the same direction well before reaching it. Only then can you make the turn to avoid it.

A memory forever imprinted in my brain is encountering a series of boulders speeding down a West Virginia river. After bypassing two boulders, we all felt we had mastered this group maneuver. However, a moment of complacency led to a head-on collision. Instead of turning the raft over, it spun us around, and we were then flowing backwards down the river. This was not a comfortable feeling. After bouncing around another boulder, thankfully, we were saved by an eddy—a patch of calm waters formed where water flowing upstream meets the downstream current—where we righted our raft.

Here we are today, enduring a pandemic-epidemic of addiction and fatal overdoses. This dire situation presents SMART with tremendous opportunities to grow and improve to help a lot more people. Our plan has identified many of the boulders. Working together, paddling in the same direction, we will navigate around them. We will make mistakes, and we will learn from them, as SMART has taught us.

A SMART Meeting for Everyone

I invite anyone in the SMART community to help us take the many action steps associated with this strategic plan. We are finalizing the details and forming numerous task forces and committees in a broad-based creative enterprise to grow and rebuild SMART USA. Our goal is no less than having a SMART Meeting for Everyone.

I am eager to hear your thoughts on any or all of the thoughts above. In the meantime, stay strong and depend on one another.

Together we are SMARTer, together we make a difference.

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

I stumbled upon this interesting study that’s based on a thought experiment. Researchers asked smokers the following question, “Imagine that a new ’clean’ nicotine product has been developed. This new product is as satisfying to use as smoking cigarettes. It is also as addictive as cigarettes, but it is far less harmful than cigarettes. It also costs slightly less than cigarettes. How interested would you be in using this product?“

Some of their findings are discussed as follows [emphasis mine]:

Our research found that smokers simultaneously support the use of a hypothetical clean nicotine product for harm reduction purposes, while also holding negative attitudes towards clean nicotine for long-term maintenance of nicotine addiction. This may partly be due to the stigma associated with the term “addiction” (Wigginton et al., 2016b). There is often a moral element to perceptions about addiction, and those who are addicted can be perceived as weak-willed, and lacking in personal responsibility (Thompson, Pearce & Barnett, 2007; Wigginton, Morphett & Gartner, 2016a). When discussing smoking and treatment, smokers often refer to the importance of willpower, personal choice and autonomy, all of which are greatly valued in contemporary society (Morphett et al., 2013, 2015; White, Oliffe & Bottorff, 2013). Nevertheless, it is clear that there is a significant proportion of smokers who wish to end their addiction to smoking who also do not want to replace their addiction to smoking with addiction to an alternative nicotine product (Morphett et al., 2015; Wigginton et al., 2016b). They should be supported in this goal, however it should also be the responsibility of health professionals to provide smokers with accurate information about the relative risks of all nicotine products, so that they can make informed choices (Kozlowski & Edwards, 2005; Lynn T. Kozlowski & Sweanor, 2016). Given the aversion to addiction observed in this study, informing consumers about differential addictiveness may influence their product choices.

I don’t find it at all surprising that smokers would prefer to be free of nicotine addiction. What I find interesting here are the assumptions of the authors.

This would appear to be an expression of an internal locus of control — an expression of their values, preferences, and goals. However, it appears to be understood as a product of an external factors and resulting personal pathology — social stigma, moralizing, misperceptions related to will-power and personal responsibility, and values held by society.

I suppose the other interesting assumption is that addiction could be a neutral to positive experience if only we can successfully minimize the harms.

I may be wrong, but I read the use of “however” as implying that this wish is to be indulged despite the irrationality.

If we can assume, for a moment, that this preference is an expression of their true, self-determined values, goals, and preferences, rather than internalized stigma, a moral reflex, or a capitulation to social pressures, what does this say about the experience of addiction? Even when the addiction is not disabling or harmful?

I’d suggest that it implies the experience of addiction is an experience of impaired control — wanting to stop, wanting to be able to stop. Even in the absence of harm, no one would choose to have impaired control over oneself. (Of course, the possibility of harm-free ATOD addiction exists only as a thought experiment.)

If we’re willing to grant them enough agency to suspend the theory that it’s a product of internalized stigma, the fact that many people with nicotine addiction would reject a theoretical harm-free nicotine addiction suggests that, for many, there’s no such thing as harm-free ATOD addiction.

The majority of treatment for drug and alcohol problems is outpatient. Trying to achieve abstinence can be tough and some evidence suggests it is more likely to be the goal of clients than the aspiration of professionals for their clients. How well do clients do?

This study by Gerald Cochrane and colleagues from New York looked at those clients maintaining abstinence in early treatment and compared them to those who found it harder. They looked at big numbers (almost 500 patients) to see what was going on.

The folk who tested negative for drugs early on didn’t seem to have worse drug problems, but they did have better mental and physical health and they were less likely to use more than one drug. The thing that caught my attention was that the patients evidencing abstinence also had much higher attendance rates at 12-step mutual aid groups.

They reported:

“a striking behavioral difference among the drug positive versus -negative samples in their utilization of 12-step programs in the 90 days prior to baseline assessment. Twelve-step attendance was endorsed by 69% who were abstinent from alcohol at baseline, compared to 40% of those reporting alcohol use in the past 7 days… Among cocaine/stimulant users, 74% of those testing negative at baseline reported 12-step attendance (compared to 49% of those testing positive).”

The authors conclude: “This study provides new data about the resilience of those who test drug-negative early in treatment by showing that many participants are already attending 12-step programming prior to treatment entry, especially for primary alcohol and stimulant users. In specific terms, a substantial percentage of alcohol (69%) and stimulant (74%) abusers who had stopped using their primary drug by the early treatment assessment reported recent involvement in 12-step programs.

And it looked like starting to go to meetings before treatment began was associated with better outcomes (my emphasis):

Mean days of 12-step program attendance in the past 90 days among negative stimulant and alcohol users suggests that self-help treatment may have been underway for some time before the formal treatment program had begun. Such proactive behavior represents an important strength that these individuals bring to the current treatment episode.”

There are questions around whether more resilient people choose to go to mutual aid or whether mutual aid makes them more resilient, but if we look at the growing research on the benefits of developing healthy social networks, then even if the former is true, the latter (going to mutual aid makes you more resilient) is also likely to be true, as this study says, and ought to be encouraged at all points on the recovery pathway as part of the process of building recovery capital.

Although this study is about 12-step mutual aid, we can make a reasonable assumption that it might also apply to SMART or other mutual aid groups (or indeed for those who attend more than one type) as the emerging evidence suggests.

This study found that early abstinence ‘is common among substance users entering treatment with a range of primary substances of abuse including alcohol, marijuana, cocaine/stimulants, and opioids.’ We have evidence from elsewhere that longer term sobriety and improved quality of life are associated with continuing mutual aid attendance.

There are three challenges for treatment services and the professionals who work in them around this research. The first is that not every service has mutual aid on its radar. Even now with increasing evidence, there is still not enough awareness of its value. The second is that there is still some prejudice against 12-step groups. You don’t have to look too far to find it. And the third is that while the importance of mutual aid might be recognised in an increasing number of places, we could be better at building bridges from treatment to mutual aid.

Note: this is a lightly edited version of a previously published blog.

Photo credit: istockphoto.com/KatarzynaBialasiewicz (under license).

A central strategy of the new recovery movement is sharing our stories in public and professional venues to change public perceptions and public policies related to addiction and recovery. Drawing from earlier social movements, we learned that “contact strategies”—increasing personal contact between marginalized and mainstream populations—is one of the most effective means of reducing stigma and discrimination and expanding opportunities for full community participation. Public attitudes toward those recovering from alcohol and other drug problems become more positive when members of the public have positive exposure to people living in long-term recovery with whom they can identify.

We also learned that there were limitations to this approach of public recovery storytelling. Changing personal attitudes of those exposed to our stories left in place much of the institutional machinery (e.g., laws, policies, and historical practices) that negatively affected individuals and families experiencing alcohol and other drug problems. Twenty years into the new recovery advocacy movement, discrimination against us remains pervasive. We must remain vigilant to prevent appropriation of our stories by others to support unrelated agendas. When this happens, we experience further marginalization.

People in recovery face discriminatory barriers in housing, employment, education, professional licensure, health care, and numerous arenas of public participation (such as voting and holding public office). Laws and regulations intended to protect us from discrimination remain unenforced. Addiction treatment remains of uneven quality, often lacking in long-term recovery orientation, and limited in its accessibility and affordability. Too many communities lack long-term recovery support services. And people in recovery continue to be excluded from meaningful representation within alcohol and drug and criminal justice policy discussions and decisions.

It is in this context that we must be clear about what our public recovery storytelling can and cannot achieve, and relatedly, who precisely is responsible for eliminating entrenched policies and practices that have such a direct impact on our lives.

There is a paradox within our anti-stigma efforts. We must challenge oppressive barriers to recovery and full participation in community life. As Frederick Douglass so clearly and eloquently stated, “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” Historical inertia and personal and institutional self-interests sustain structures of oppression until they are challenged. Who will pose such a challenge if not people in recovery? Yet the ultimate responsibility for dismantling discriminatory practices rests upon the shoulders of the systems within which such oppressive machinery continues to operate. The responsibility to eliminate discrimination rests with those who discriminate. By itself, telling the perfect recovery story will not end discriminatory practices.

So where does recovery storytelling fit into all this? Our stories are a means of humanizing addiction and recovery—a means of challenging the myths, misconceptions, and caricatures that have let others objectify and isolate us. Our stories are an invitation for people to reconsider the sources of and solutions to alcohol and other drug problems. Our stories are a means of building relationships that embrace us within the human family—as people who share the dreams and aspirations of others. Our stories, directly or indirectly, also constitute Douglass’ demand to change the structures that have prevented embrace of our humanity and rendered us people to be feared, shunned, or punished. This involves far more than changing people’s perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward those with lived experience of addiction and recovery. It involves identifying and eliminating the precise mechanisms (e.g., policies and practices) through which social shunning and discrimination have been institutionalized.

This is not to suggest that people in recovery have no role to play in this change process nor that we should passively embrace a victim status in the face of such systemic challenges. We can take responsibility for our own personal and family recovery, make amends to those we have harmed, and reach out to others still suffering. We can participate in recovery-focused research (to create a science of recovery that can challenge recovery misconceptions), participate in protests and advocacy efforts, offer our recovery stories in public and professional educational venues, and represent our lived experience within policy-making settings. Such actions have contributed to numerous positive changes.

Our stories possess immense power as long as we recognize our stories alone will not create recovery-friendly social institutions or recovery-inclusive communities. We must not allow our stories to stand as superficial window-dressings while discrimination remains pervasive, even among some of the very groups and institutions who on the surface support our storytelling. Our stories must support specific calls for institutional change. We must hold individuals and institutions that discriminate accountable until they eliminate such conditions.

How we craft and communicate our stories for public/professional consumption is an important element of this process of social change. Recovery advocacy organizations have a responsibility to prepare and support the vanguard of individuals who heed the call of this public story-sharing ministry. This includes building a community ethic that protects those who possess the bravery and privilege of sharing their recovery stories in public forums. Collecting our stories without meaningful dialogue about how our stories will be used and the protections we will be afforded is unacceptable.

This is the first in a continuing series of blogs on personal privacy and public recovery advocacy. We hope it will set recovery storytelling within a larger context. The remaining blogs will explore the risks of public recovery storytelling, the ethics of public recovery story sharing, and suggest guidelines on protecting personal privacy and safety within the context of public recovery storytelling. The impetus for this series comes from our knowledge of individuals who have experienced unanticipated harm related to their advocacy efforts.

Link to Bill White Papers web site HERE

The 2020 SMART Recovery East Coast Conference was a success! Thank you to the presenters and guests for attending.

For those who were unable to join us on October 24th, and for everyone who wishes to watch it again, the entire conference is now available.

The six hour program includes presentations from:

- Bill Greer, SMART Recovery Board President

- Christopher C. Wagner, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Licensed Clinical Psychologist, Virginia Commonwealth University College of Health Professions – The Special Challenges of Motivational Interviewing in Groups

- Carrie Wilkens, Ph.D., Co-Founder and Clinical Director, The Center for Motivation and Change, New York; New Marlborough, MA; and Washington, DC. – Inviting Change Through Empathic Understanding: The Invitation to Change

Dr. Wagner’s book – Motivational Interviewing in Groups

Dr. Wilken’s book – Beyond Addiction: How Science and Kindness Help People Change

View the full video on our YouTube channel

Thank you again to the sponsors:

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Substance use disorder is something that impacts everyone in the wake of the disease…especially family members, close friends, and loved ones. When someone you love is suffering from the disease, they act in ways they would not typically act under normal circumstances. This can consume your life, and can often make family life feel unmanageable.

Establishing boundaries is an incredibly powerful way to manage the way that substance use disorder impacts your family life. Healthy boundaries help establish guidelines for living and relating to others. If they are reasonable and clearly communicated, they provide security for everyone involved. Boundaries prepare you for what to expect in your relationships, and likewise, what might occur if that expectation is not met.

What are boundaries and why are they important?

When a loved one is active in their disease, everything in life can begin to blend together. Their problems become your own, and the line between where their suffering ends and yours begins can become undetectable. A boundary must be something that is measurable and specific, reasonable, and enforceable.

Boundaries allow you to detach with love–not from the individual, but from the disease itself. When you detach with love, you stop protecting the disease. Boundaries provide you with a sense of individuality and allow you to focus on your feelings, problems, and needs, which ultimately allows you to better support your loved one in need.

Recovery is multi-faceted, one component being the recovery and healing of the family. Communication, vulnerability, and strong boundaries are some of the most important components of family recovery.

What should you set boundaries around?

The need for specific boundaries can vary, but here are some helpful things to think about when assessing your personal situation:

- How will you allow others to treat you?

This protects you from being harmed by others.

- How will you treat others?

This protects others from being harmed by you.

- How will you treat yourself?

This allows you to regulate your physical, emotional, and spiritual health.

Some examples of specific boundaries are:

- No substances, nor persons under the influence are allowed in the house

- No disrespect is tolerated

- I will not purchase alcohol or substances for you (your loved one)

- I will not give you money for said substances

Base boundaries off of how you feel…

You will know a boundary has been violated based on your emotions. What specific things make you feel anxious, upset, or stressed? These are the things that you should be working to set boundaries around.

Have an open and honest talk as a family with your loved one

It’s not what you say, but how you say it. Establish open communication with your loved one in recovery, or in active use, and make your boundaries clear to them. State your parameters, and the consequences that will occur should those boundaries be violated. For example, if you tell your loved one that no drugs or alcohol are allowed in your home, they must honor that. You might convey to them that if they violate this boundary, they must find somewhere else to stay.

Because the disease feeds on gray areas, loopholes, and blurred lines, make your expectations as clear as possible.

Seek additional support

One of the ways to heal yourself is to take the time to do so. When a loved one is suffering, it can become so ingrained in you to help them that you forget to help yourself. Though often forgotten, self-care makes you more sensitive to the needs of others and ourselves. Do things that support your personal well-being—pray, meditate, paint, exercise, etc.

As you work to take care of yourself and support your loved one in recovery or in need of recovery, seek the collective wisdom and support of a 12 Step group such as Al-Anon or Nar-Anon. To find a meeting in your area, visit https://al-anon.org/ or https://www.nar-anon.org/find-a-meeting

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, ‘like’ the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.