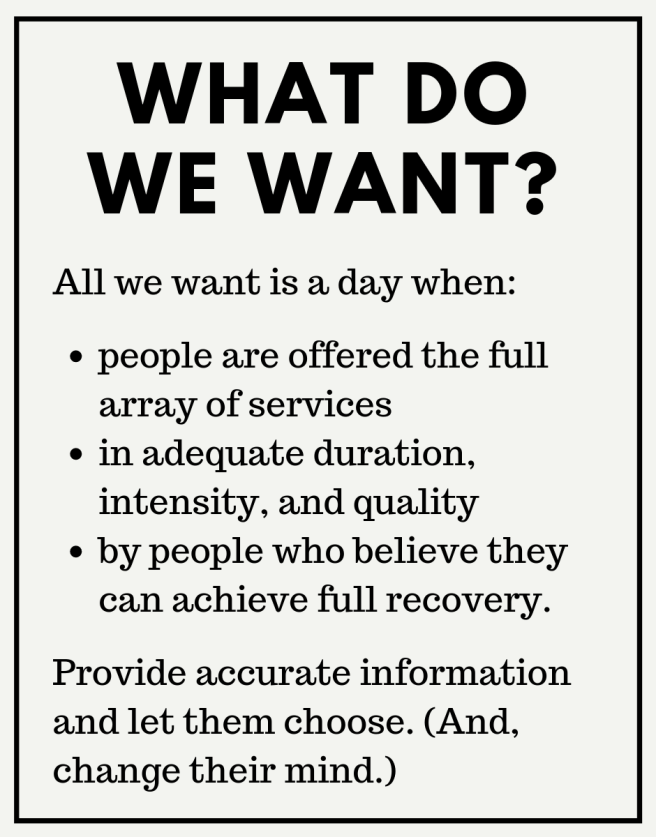

The quote below is from a piece that compares San Francisco’s drug plan to Portugal. The author appears to be an advocate of a comprehensive response to San Francisco’s drug problem — criminal justice reform, harm reduction, treatment, etc. — so she definitely is not making an argument against harm reduction.

She refers to an interview with Dr. Joao Goulao, Portugal’s Director-General of The General Directorate for Intervention on Addictive Behaviours and Dependencies. This portion speaks to the role of treatment in Portugal’s system.

One point he made tripped me up, because it’s so foreign to San Francisco. Here there are long waiting lists for many services, including drug treatment. Is there really always a spot in a drug treatment facility available in Portugal?

“Always,” he said, looking surprised by the question. “Always.”

He said the country spends 75 million euros — about $85 million — on drug treatment each year.

The approach means Portugal never had to open a safe injection site

Dr. Goalao says that Portugal has plans for supervised injection sites next year but the author adds, “But the concept is in addition to the country’s approach to drugs, not its entire plan, like here in San Francisco.”

The whole piece is well worth reading but it is behind a paywall.

There are 200 deaths a day related to the opiate crisis in the USA. In Scotland we have the highest number of drug-related deaths in Europe, perhaps in the world. A task force set up by the Scottish Government has recommended six interventions to tackle our crisis which we hope will make a difference. I am increasingly convinced though that something is missing – something which could make a significant impact.

Getting plugged in

The concept I’m contemplating is simple and it’s not my idea by any means. It’s this: healthy social networks (the people we connect with) are protective. Improving them brings gains in physical and mental health. People suffering with addiction frequently have damaged or unhealthy social networks. They are often dislocated and estranged or excluded from being active community members. As I say, there is existing evidence on this, though there are serious questions about how far it has penetrated into the practice of treatment providers or commissioners.

If we look at existing research, there’s no better place to start than examining the impact of social networks on longevity and wellbeing. In 2010, Julianne Holt-Lunstad and her colleagues undertook an impressive meta-analysis (massive review of the evidence available) to see how social relationships influenced mortality. They found a protective effect for those with stronger social relationships. In fact, for this group there was a 50% increased likelihood of survival. In medical terms, this is a very large effect – similar to stopping smoking. You want to live longer? Get lots of friends.

Mark Litt and his colleagues explored this concept in alcohol-dependent men and women in 2009. In a high-quality trial, they tested out linking individuals into new pro-abstinence networks vs. other established treatments and found that those who formed new connections (in mutual aid) did better than established treatments. A stunning finding was that:

the addition of just one abstinent person to a social network increased the probability of abstinence for the next year by 27%.

Litt found that drinkers’ social networks can be changed by a treatment that is specifically designed to do so, and that these changes contribute to improved drinking outcomes.

So how are we doing on this front?

If we could get this sort of impact from medication in alcohol treatment settings, we’d be very happy, and if you are like me, you’ll be thinking, ‘lets go for it!’ Yet when commissioners asked 250 addiction treatment service users in Edinburgh in 2010 how many of them had ever been to a mutual aid group, the answer was less than 1%.

This is pretty dismal. In 2010, we weren’t doing very well in the city of Edinburgh. My hope is that if this was repeated today, we’d see an improvement. But would it be enough?

Getting equipped for recovery

The two papers that caught my eye this week which are relevant to this topic are worth a read. I’m not going to analyse them here, but I will pick out some key points. In the first ‘Are members of mutual aid groups better equipped for addiction recovery?’, Thomas Martinelli and colleagues interviewed 367 people in recovery from drug addiction and looked at how membership of mutual aid groups related to things like social networks, recovery capital and commitment to sobriety.

They recruited the participants in Belgium, the Netherlands and the UK by a variety of methods including social media, newsletters, conferences, posters, flyers, magazines and by contacting prevention and treatment organisations. Participants self-identified as being in recovery for at least three months and completed a questionnaire.

Findings

Interestingly, 69% reported membership of mutual aid groups at some point. When lifetime mutual aid members were compared with non-mutual aid members, some differences appeared with significant benefits to the mutual aid group members. These were identified in things like: paid employment (64% vs. 45%); abstinence from drugs (94% vs. 75%) and abstinence from alcohol (81% vs. 52%).

For those who were using drugs or alcohol, using days and drinking days were 3 times higher in the non-mutual aid group. There were strong associations with improved social networks, increased recovery capital (and ability to sustain recovery) and commitment to recovery for mutual aid group members. Those who were current members of mutual aid groups consistently reported more resources than those who had been members in the past. The benefits were greatest for members of 12-step groups, but positive outcomes did extend to non 12-step groups too.

Bottom line?

the expanding evidence on the benefits of mutual aid group participation should justify further exploration of its inclusion into system-wide practice of addiction services and to encourage services to refer to mutual aid groups

Getting a dose of recovery

In the other paper which focuses on the negative issues associated with social networks – ‘Social network theory—an underutilized opportunity to align innovative methods with the demands of the opioid epidemic’, Christina Cutter and colleagues point out that demand for opioid use arising from social networks and environment is an important contributing factor to the current opioid crisis.

Previous research on behaviours shows cluster effects (e.g. around obesity, suggesting that if you want to lose weight, you should hang around with thin friends). They recommend that we explore the ‘social contagion model’, an approach which puts forward that behaviours develop through role modelling and spread as if they are infective.

Their argument focusses on the problem (how opiate addiction spreads) and they express how understanding and exploration of this could help develop new strategies. They powerfully describe the issue of ‘social networks of despair’ arising from overdoses and deaths, but they also shine a light, turning things around and presenting the opportunity for the social contagion model to operate as a catalyst for recovery. I often paraphrase this as ‘if you hang around people in recovery long enough, you are likely to catch a dose of it.’

Indeed, the authors give mutual aid (AA) as an example of how this is done. After all, AA has now been shown to be as effective, if not more effective, than other evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Fittingly for these times, Cutter et al extend the contagion model and highlight the process for a cure:

the expanding evidence on the benefits of mutual aid group participation should justify further exploration of its inclusion into system-wide practice of addiction services and to encourage services to refer to mutual aid groups

The recent announcement of a vaccine against covid-19 has generated phenomenal interest and jubilation. Hope now flows where hopelessness lingered. Perhaps, as with covid-19, we need more than one vaccine against drug and alcohol problems to be researched, but hang on a minute! A cheap, tested, evidence-based vaccine already exists – assertively connecting people to mutual aid! This would appear to have a very significant impact on outcomes compared to most interventions.

Now, I’m not claiming this approach as an answer to our opiate (and alcohol) deaths. There is no single answer. What I am saying is that we ought to vigorously test out the social contagion/social networking model as part of the range of interventions we are currently adopting – the evidence is already strong and accumulating.

I’d like to see this approach at the heart of all of our interventions and have services held to account on how effectively they link service users into new social networks. Then I think we would really see change.

The is a post was initially published in 2018. Please note that abstinence can mean abstinence from illicit drugs, or abstinence from all drugs that produce euphoria or are commonly misused (including agonist medications, benzodiazepines, etc.). For the purposes of this post, this distinction is irrelevant because the arguments in the second article really apply to either definition of abstinence.

I was perusing past year articles in Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly and came across these two:

Achieving a 15% relapse rate

Article one, as the title suggests, examines Collegiate Recovery Programs (CRPs) and Physician Health Programs (PHPs), their outstanding outcomes, their common elements, and discusses their potential for application to other populations. The abstract introduces them this way [Emphasis mine. The reason will be obvious later.]:

The CRP and PHP models involve long-term, comprehensive components of care and ancillary services oriented toward highly transformative abstinence-based recovery.

The text of the article adds this:

Both models hold the maintenance of long-term abstinence as the general outcome of choice.

The closing discussion opens this way:

Is a 15% relapse rate attainable? Evidence would suggest that common factors among pockets of highly successful recovery may hold the ingredients needed to ensure low relapse rates for all addiction treatment. CRPs in particular provide an example of recovery supports that facilitate long-term recovery through addressing recovery and quality of life concerns concurrently, while the individual works to achieve greater social capital through education.

Expanding services and support to include broader depth and coverage of socioeconomic, ethnic, and other disparities that exist in the current system is of paramount importance if we are to see real societal change and test the efficacy of the PHP and CRP models. PHP clients, consisting of licensed professionals, obviously garner esteem, social credibility, and seem “worthy” of saving from addiction. In the same way, so do young people who have the wherewithal to engage in treatment and be successful in higher education.

“Motivational Interviewing cannot be used in its fidelity in abstinence-based treatment”

Article two makes the following argument:

A major underpinning of motivation interviewing is to “meet clients where they are at,” and tailor interventions to their specific stage of change. In abstinence-based programs, however, clients are immediately placed in the action stage of change, even skipping the preparation stage of change that is essential to maintain recovery. Furthermore, this choice is made for them, not only evidencing the inability to do MI, but also the lack of individualized treatment. Despite this disconnect, the abstinence-only approach is still used in many treatment facilities in the United States, with 72% of facilities providing 12 Step-based programs (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2017), which are abstinence based and noted as what someone must achieve it to attain recovery, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; 2016). It is important to highlight, however, that our position is not that 12-Step programs are not useful or ineffective. Conversely, 12-Step programs have withstood the test of time and are a valuable resource for many. What we are suggesting is that 12-Step programs are not for every client and, therefore, should not be the core of treatment programming. Rather, we propose individualized treatment consistent with the underpinnings of MI, which includes assessments, treatment planning, and counseling sessions based on harm reduction, not abstinence. Although abstinence is an excellent goal for recovery, the culture of a treatment agency cannot determine the goals for clients, which obviously is the opposite of individualized treatment. The clients themselves must determine their own treatment goals. MI continues to gain popularity and was reportedly being used in 90% of treatment programs (SAMHSA, 2017). Based on these findings, it seems that many facilities are employing an abstinence-based philosophy while also attempting to use MI. The following sections discuss how MI cannot be used in its fidelity in abstinence- based programs, despite many claiming to do so.

I’d argue that the framing here leaves a lot to be desired.

First, they cite that 90% percent of programs report using MI, but argue that most cannot be implementing MI with fidelity to MI principles because 72% report “providing 12 step-based programs.” IF these are incompatible, who’s to say that the infidelity is on the MI side? Couldn’t it be on either side?

Second, it’s worth noting that the SAMHSA report does not report on programs “providing 12 step-based programs.” Rather, the report tells us how many programs report using “12 step facilitation” (TSF). That distinction is important. The difference between a program that reports “providing 12 step-based programs” and one whose toolbox includes TSF is significant. The former implies that the 12 steps are the foundation for the entire program and are used with 100% of patients. The latter implies that TSF may (or, may not) be used with patients. In fact, the report indicates that 47% of programs report using TSF “always or often.” The survey provides no definition or guidance for “often”, leaving it pretty subjective.

Why would the authors characterize the data in this way? IDK

Further, earlier in the article they present the Minnesota model as representative of contemporary treatment services. However, the same report indicates that residential/inpatient treatment represented only 9% of all admissions in the report, and who knows what portion of that 9% received services resembling the Minnesota model? Another confusing, rather than clarifying, representation.

Treatment goals

So, article two appears to say that services with a goal of abstinence cannot be faithful to MI.

Is abstinence an appropriate goal in treatment? And, how should providers determine what goal(s) they want to organize their programs around?

A lot of this comes down to the nature of the problem you are treating, whether the problem is a behavior or a disease.

If we’re treating addiction (whose hallmark is impaired control), then abstinence is the goal that’s going to provide quality of life. AND, as the first article demonstrates, we have approaches that can deliver high rates of success.

If you’re addressing a lower severity problem, harm reduction or moderation are often good endpoints to focus on. These kinds of users can probably reduce harm and maintain a good quality of life.

Imagine we were discussing some other illness with severe physical, psychological, social, familial, occupational, and spiritual consequences. Further, imagine there are treatments what deliver relapse rates as low as 15%. Imagine there are barriers to engagement and retention in these treatments, and you wanted to use MI to improve engagement. Would it be inappropriate to have services organized around the goal of engaging and supporting patients in these effective treatments?

Which goals should take priority? Engagement rates in these successful treatments, or fidelity to the MI model?

What would we think about a cancer treatment program that takes no position on treatment options, and prioritizes symptom reduction and patient choice over remission?

To me, the authors of the MI article seem to be focused on AOD use as a behavior rather than a symptom of a disease.

It’s possible that they are focused on lower severity SUDs, or they don’t believe addiction is a disease, or they don’t believe there are meaningful differences in good care for addiction and lower severity SUDs.

It’s worth noting that the word “disease” appears only once in the article, and only when describing the Minnesota model.

I have no quarrel with their high-fidelity version MI model for lower severity SUDs, and I have no problem with it as a model to engage high severity SUDs (addiction) into other effective treatment models. (See posts about gradualism and recovery-oriented harm reduction.)

What are we treating? What are we seeking recovery from?

I imagine, maybe incorrectly, that the authors and I disagree on addiction as a disease.

I believe that addiction is a brain disease, and I like the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s definition:

Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors.

Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death.

Within the field, however, there once again seem to be growing doubts about addiction as a disease.

Some see it as an outdated metaphor or useful fiction, while others see it as an artifact of stigma, and others see it as a social ill. (It’s paywalled, but the NEJM just published an argument that addiction is a learning disorder and not a disease.)

Many of these models of understanding started outside of the field, but are being brought into the field, knowingly or unknowingly, by new professionals and advocates.

The problem is made worse by the DSM 5’s movement toward a continuum model which puts all AOD problems on one continuum/category. No longer are low severity problems and high severity problems categorized as different kinds of problems. Rather, they are now one kind of problem with different severities.

Fuzzy thinking?

I’m not an expert in MI, but I’m not sure I buy the argument that fidelity to MI demands that practitioners and programs be agnostic on abstinence as the ideal outcome for addiction. And, if it does, I wouldn’t want my loved one in a program that is neutral on the outcome associated with the highest quality of life.

So . . . what’s going on then?

Dirk Hanson offered a helpful observation a few years ago about the relationship between harm reduction advocacy and the disease model.

For harm reductionists, addiction is sometimes viewed as a learning disorder. This semantic construction seems to hold out the possibility of learning to drink or use drugs moderately after using them addictively. The fact that some non-alcoholics drink too much and ought to cut back, just as some recreational drug users need to ease up, is certainly a public health issue—but one that is distinct in almost every way from the issue of biochemical addiction. By concentrating on the fuzziest part of the spectrum, where problem drinking merges into alcoholism, we’ve introduced fuzzy thinking with regard to at least some of the existing addiction research base. And that doesn’t help anybody find common ground.

UPDATE: I suppose it comes down to whether one sees MI as a complete treatment.

No one would ever consider MI a treatment for cancer, but we might think of it as good practice to engage patients into treatment.

If you see your patient’s SUD as a behavioral issue, MI is the complete package.

If you see it as a disease, for which there are effective treatments, it’s a treatment engagement model.

Provided by Michael Hooper, Veteran and SMART Recovery State Outreach Director for Ohio

Through my journey with SMART Recovery, I have seen certain tools hold immediate weight with the participants of the Veteran and First Responder communities frequenting my meetings. One of the defining reasons why these particular tools ring true to so many of them right away, I believe, is the fact that these tools have the ability to be used in a practical manner almost immediately. Many of the SMART Recovery tools, such as the ABC tool, need time and focus to be properly applied. Based heavily off of CBA techniques, tools such ABC are meant to be utilized in a manner where the participant has time to analyze and deconstruct certain life situations in order to break down the root of a problem. Though highly effective and indeed practical, a tool such as this takes time to master before it can be used in an expeditious manner.

The tools I am including have been proven to not only be useful in a number of different life scenarios (not just addiction related) but can also be used with little to no experience in recovery. Veterans and First Responders adhere quickly to this type of methodology due to our training being similar in many regards. They are expected to comprehend many different training aspects with minimal instruction as these techniques are meant to be used in strenuous situations where cognitive thinking may be impaired. As a result, participants are forced to rely on instinctual reaction or “muscle memory”, so to speak. The following tools can be regarded as the “muscle memory” tools of SMART Recovery as they are easily learned and can be utilized and practiced almost immediately upon assimilation.

Hierarchy of Values (HOV)

A tool asking the participant to identify what is most important to them within their lives. This tool is helpful to aid the participant in focusing on what is most valuable to them and their motivation to create change in their lives, thus contributing to Point 1 of SMART: Building and Maintaining Motivation.

Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA)

This tool outlines the pros and cons of the participant’s addictive behavior, and the same for practicing abstinence from that particular behavior in their life. What is unique about this method for SMART Recovery is that it also defines whether or not these traits have short or long-term effects on their lives. The immediate usage of this particular tool is obvious and, therefore, has been held in high regard by participants.

Disputing Irrational Beliefs (DIBS)

Thoughts can affect our emotions, and our emotional states can influence our actions. Learning to identify unhelpful thoughts and defusing them before they become problematic, is one of the first skills we value in the SMART Recovery Program. Learning how to identify whether a thought is logical, based in fact, and/or is helpful to our current state of being in recovery, can be an essential tool for combating urges, cravings, and triggers; this is Point 2 in our Program.

Deny/Delay, Escape, Avoid/Attack/Accept, Distract, Substitute (DEADS)

One of the most effective tools in the SMART Recovery arsenal for coping with urges and cravings, in my opinion, is the DEADS tool. The DEADS tool is helpful because it is what I like to classify as a “Crisis Management Tool.” This tool can be used with little experience in recovery, and offers multiple pathways to combat an occurring urge or craving.

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Background

David McCartney wrote a great post about the PHP model of care that addicted physicians receive and its outstanding outcomes.

David framed the PHP model as the gold standard treatment. I also frequently call PHPs the gold standard.

I recently shared an interview with Robert DuPont discussing his discovery that his methadone patients were dying of alcoholism. This prompted David to look more closely at the relationship between opioid use disorder and alcohol use disorder.

All of this raises questions about the nature of the problem and the target for the treatment. In the case of addictions, should we think about substance use problems as discrete disorders characterized by problems with a particular substance? For example, does someone addicted to alcohol, opioids, and cocaine have 3 disorders (AUD, OUD, CUD)? Or, do they have one disorder (drug addiction)?

Brian Coon responded with a great and provocative post asking whether it’s accurate to describe any current treatment as a gold standard.

In his post, Brian points out that advocates, researchers, physicians, and public health professionals often call opioid agonist treatments the gold standard for Opioid Use Disorder.

Brian wonders whether anything should be called the gold standard when the norm in addiction treatment is failure to adequately address smoking. He zeroes in one 2 big concerns about this failure. First, the illness and death caused by smoking. Second, can we say we’re effectively treating their addiction while we’re not adequately addressing their addiction to tobacco?

(Check these out for previous posts from David and Brian on tobacco/nicotine.)

Gold standard?

Should PHPs be called the gold standard? Let’s look at the definition.

The best or most successful diagnostic or therapeutic modality for a condition, against which new tests or results and protocols are compared.

McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine

This definition suggests that the designation is relative to other treatments, rather than an indication that it’s the best treatment possible, so use of the term seems appropriate.

The label has been applied to both PHPs and opioid agonists. Which should be called the gold standard?

Well . . . the definition has 2 parts: being the most successful treatment, and being the benchmark against which other treatments are compared.

Most successful treatment? – I’d say that PHPs could make the case for being the most successful treatment.

Benchmark? – In practice, it’s very clear that agonist treatments are the benchmark for opioid use disorders.

Availability? – Other definitions describe the gold standard as the “best available” treatment. The PHP model is not widely available, but agonists are.

Now, I don’t believe Brian was focused on technical application of the definition of gold standard. Rather, he was focused on our blind spot with smoking while more people die of tobacco related illness than from opioids or COVID-19.

The problem of tobacco

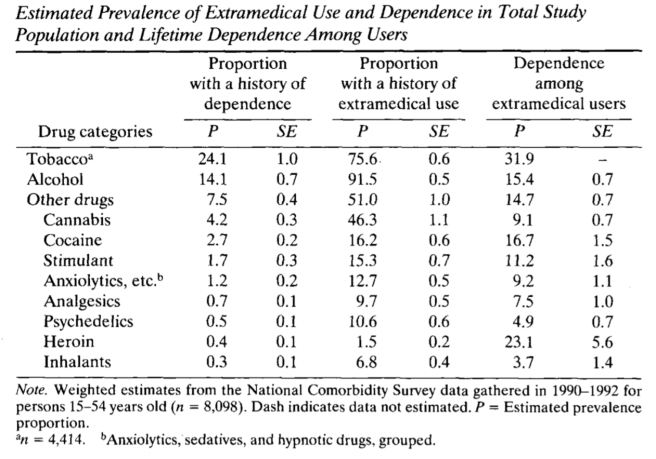

Tobacco and nicotine addiction has interested and confused me for as long as I’ve been interested in addiction.

The case for aggressive treatment of tobacco dependence among SUD treatment recipients is clear and compelling. Consider the following:

- It contributes to more illness and death than alcohol and all other drugs combined.

- Rates of tobacco use among addiction treatment seekers is more than 5 times the general population.

- People with other substance use problems have greater difficulty quitting tobacco.

- Most smokers in addiction treatment would like to quit.

- Quitting smoking during treatment is associated with better treatment outcomes.

- Research has identified tobacco related illness as the leading cause of death for people who had been treated for alcoholism.

Despite all of this, we’ve failed to impact tobacco use in ways that correspond with its threat to recovery and health. Why?

Further, when systems respond in ways that treat tobacco as a serious threat to health and recovery, it evokes intense resistance.

Nicotine addiction is weird

Why do we fail to impact tobacco use in ways that correspond with its threat to recovery and health?

There are some obvious potential explanations–indifference, denial, avoidance, etc. These all undoubtedly contain some truth. And, I think we treat tobacco differently because there are noteworthy ways in which it is different.

- Tobacco does not cause the kind of euphoria we associate with other addictive drugs.

- Yet, it has a higher “capture rate” than cocaine, heroin, and alcohol. (capture rate = the % of users that will become chronic users of the substance)

- It isn’t associated with the kind of short term impairment in cognitive or motor function that we see with other substance use.

- It isn’t associated with the kind of role impairment we see in other addictions.

- Its most serious consequences are delayed by decades and have a very gradual onset.

- It’s a legal substance and, while use may be restricted in certain places, its use isn’t generally prohibited before or during work hours or while driving.

- Its legal status and its widespread use in the recovering community complicate efforts to simultaneously facilitate involvement in the recovering community and abstinence from tobacco.

- While there is growing empirical knowledge about the adverse effects of smoking on addiction treatment outcomes, this appears to be outside of the awareness of the user and those around them. Almost no one attributes their relapse to tobacco use.

- While there is growing empirical knowledge about the adverse effects of smoking on addiction treatment outcomes, the recovering community’s experience is people achieving decades of recovery while continuing to smoke.

- We’ve gotten millions of people to quit with tools like taxation and social control around where and when people can consume tobacco.

- I haven’t seen evidence that these people moved on to other substances.

- Strategies like taxation and social control seem inadequate to impact other drugs in the same way.

- People in recovery often report that the strategies that helped them stop using other drugs are not very helpful with tobacco.

What, exactly, do we really care about?

Much of Brian’s attention is on the deaths and illness associated with tobacco use. What if we were able to minimize deaths and illness? Would we still care? How much?

It’s not difficult to imagine a future where vaping completely replaces tobacco and is regulated in such a way that the risks to physical health are minimal.

I know a handful of people who quit smoking with nicotine gum and have never stopped using nicotine gum, continuing to use it for years.

Would we still question treatment that doesn’t center nicotine? Would we raise questions about the quality or completeness of individual recovery?

We also know that heavy caffeine consumption is common in the recovering community–enough to result in a withdrawal syndrome. Should we consider centering this in addiction treatment and recovery?

Wrapping up

I’m not, in any way, dismissing these concerns about our failures to address tobacco in treatment and communities of recovery. (I’ve preached about this for more than a decade.)

We’ve put a lot of energy into the argument that tobacco is no different from other drugs, but I think that part of the reason we’ve made so little progress is because nicotine is different in some important ways.

I wonder if exploring, identifying, and acknowledging the ways nicotine is weird and different will help us improve our efforts.

Les Waite is a veteran and a clinical psychologist at the Albany Stratton VA Medical Center in Albany, New York. His struggles with addiction lead him to SMART Recovery. Now, he uses the SMART tools daily in his practice for veterans.

In this podcast, Les talks about:

- His educational resume that includes learning the teachings of Alfred Adler

- Serving in the military during the first Gulf War

- Seeing his comrades come back from deployment with trauma issues and finding limited professional resources to help them

- How trauma and substance use disorders are linked

- His owns struggles with addiction

- Being introduced to SMART and why he fell in love with the program

- Why the VA hospitals’ programs dovetail beautifully with SMART’s teachings

- His “been there, done that” connection with patients

- Why the structure and order of the SMART program is effective for veterans

- Playing Jonny Appleseed in the VA hospitals by starting SMART meetings everywhere he goes

- Motivational interviewing and the stages of change model

- Having honest, genuine dialog with his patients about the reasons they are seeing him

- Reconnecting a veteran to their own values using the hierarchy of values tool

- His post-COVID goals of launching more SMART meetings for veterans and in his community

Additional references:

Click here to find all of SMART Recovery’s podcasts

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

You probably had very different ideas about what it meant to be in recovery before coming to treatment. From the outside looking in, it might seem like recovery is merely abstaining from drugs and alcohol, and working a 12 Step Program. While that’s partly true, those are two very important components of your recovery, the wellness of the various areas of your life are just as important. Wellness is what makes your recovery sustainable, and helps you build a lasting foundation for your life in sobriety.

Defining Wellness…

Wellness doesn’t just mean counting calories or doing cardio once a week. Wellness is the state of being in good health overall. In fact, there are seven total areas of wellness:

- Physical

- Emotional

- Intellectual

- Social

- Spiritual

- Environmental

- Occupational

As you work to rebuild your life during your recovery, you will notice that “feeding” these seven parts of your life will only strengthen your decision-making abilities, boost your confidence and self-image, and most importantly, help you avoid a return to use.

So, what habits can you work into your daily routine to support your overall wellness?

Eating well and Staying Active

Previously on the blog, we’ve covered the multiple benefits of incorporating physical activity into your routine, specifically relating to your recovery. Essentially, eating well and staying active improves your sleep, can help improve your confidence, structures your days, and helps to reduce stress. You can read that full post here.

You also must realize that your gut and your brain are connected. What you put into your body as your “fuel” does matter, and certain foods can contribute to heightened levels of anxiety and depression. Avoiding or limiting sugary foods such as candy, soda, and juices can help regulate your blood sugar and energy levels. Switching to whole foods such as fruits, vegetables, and healthy fats can help you feel your best as you provide your body with the nutrients necessary to get through the day.

For a more in-depth look at how your nutrition can impact your anxiety, join Fellowship Hall and Triad Lifestyle Medicine on November 12th from 12:30 to 1:30 for a Wellness Webinar. Hosts Leah Hazelwood and Tiffany Allen will be leading us in a conversation about the ways we can prepare to have a healthier holiday season, managing our anxiety with proper nutrition and wellness habits.

Maintaining a Strong Spiritual Life

A rich spiritual life focuses on concepts that are foundational to long-term recovery such as (but not limited to) surrender, reflection, acceptance, honesty, and hope for the future. Habits such as prayer, meditation, and journaling are all healthy ways to stay spiritually fit. These things allow you to center yourself, to take a step back from tough situations and stressors, and to make the best decisions as you move forward in building your new big life.

Balancing Social, Environmental, and Occupational Life

Finally, your interpersonal relationships are equally as important as the relationship you have with yourself. Be mindful of the environment you live in, and work in. Identify triggers of stress or anxiety—maybe you find that you can’t work well or relax if things are messy. Work to avoid creating stressful environments for yourself.

In both your occupational and social life, be sure to reflect and “check-in” with yourself. Are you doing the best you can to get the most out of the work that you are doing? Are you connecting with your co-workers and friends in ways that are healthy for you? What boundaries are you exercising to keep yourself and others well in your relationships? Remember, if you’re unsure about work-life balance, socializing in sobriety, or even how to create the best environments for yourself, don’t be afraid to reach out. Identify the weaknesses in any of your areas of wellness and ask a sponsor or trusted member in your support network for guidance on how to improve these areas of your life so that you may further strengthen your recovery.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, ‘like’ the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

Opioid maintenance therapy (OMT), also called medication-assisted treatment (MAT), is known as a Gold Standard addiction treatment.

That’s one Gold Standard if you are keeping count.

The model of care used by Physician Health Programs (PHP’s) is known as a Gold Standard addiction treatment.

That’s two Gold Standards if you are keeping count.

But what do they really accomplish? Let’s look at some numbers. And given our current pandemic, let’s compare them to recent COVID data:

Opioids USA1 From 1999-2018 the total opioid overdose deaths = 450,000. For the year 2018 = 128 deaths per day.

COVID-19 USA2 At the time of this writing we are in the COVID-19 pandemic. The year-to-date USA COVID-19 deaths as of 11/07/2020 = 239,000. For YTD 2020 = 770 deaths per day.

Cigarettes USA3Annual USA cigarette deaths = 480,000. In 2018 = 1,315 deaths per day. That includes second-hand smoke annual deaths = 41,000. If one excludes the deaths from second-hand smoke that leaves 2018 = 439,000 deaths. And for 2018 = 1,202 deaths per day

We have two Gold Standards? How about admitting we have none?

- The “Gold Standard” of MAT and the “Gold Standard” of the PHP model both focus on disease management, symptom suppression, and promote wellness-related improvements such as personal goal attainment. And both use multi-year models.

- Both permit cigarette smoking.

- By default then, both permit dying later due to continuing one’s cigarette addiction while undergoing their addiction treatment.

If a person dies of emphysema from continuing to smoke cigarettes after their “addiction treatment” – did we really treat their addiction illness or did we just address disordered use of (for example) opioids or alcohol?

What does it even mean to claim to do addiction treatment for someone while the person continues their active addiction illness by way of addictive substance use (like smoking cigarettes) the entire time they undergo their so-called addiction treatment?

Who coined the term “Gold Standard”? Who decides what criteria must be met to claim it, and how is that decided?

Is an addiction treatment a Gold Standard addiction treatment if it treats one addiction while allowing or ignoring another – during the treatment?

Instead, what if we:

- treat the person’s whole addiction illness during addiction treatment, rather than only treat one substance use disorder (opioids or alcohol) while ignoring another substance use disorder (cigarettes)?

- rename SUD-related services as simple “SUD services” – rather than call them “addiction treatment” if they allow people to remain actively addicted while the person is undergoing their “addiction treatment”?

“So, are people getting better, or not?”

References and Additional Reading

1https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html

2https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

Coon, B. (2014). An Addiction Treatment Campus Goes Tobacco-Free: Lessons Learned. Addiction Professional. 12(1): 18-20.

Martin, L., Lee, J. L., & Coon, B. (2018). Implementing Tobacco-Free Policies in Residential Addiction Treatment Settings. Physician Health News. 25 (2):14.

White, W. & Coon, B. (2003). Methadone and the Anti-Medication Bias in Addiction Treatment. Counselor 4(5):58-63.

Berlin, like many big cities has a heroin problem. People presenting for help are being prescribed opioid replacement therapy (ORT) – a form of medication assisted treatment (MAT) in greater numbers. That’s a good thing isn’t it? Yes, but it’s not completely straightforward. A lot depends on what the professional and their patient think is the end goal of treatment.

At the start of this interesting German paper from a few years back entitled, “Why do patients stay in opiod maintenance treatment?”, Dr Stefan Gutwinski and colleagues say that the scientific literature indicates the point of opiate replacement is: “to increase survival and bring stabilization to patients, in order to enable them to reach abstinence of opioids.”

We can simplify this into two aims:

- To make things better, then

- To move on to abstinence

Many professionals would not agree with the second aim and would possibly replace it with ‘to retain in treatment’. There is an often unspoken tension between what researchers tell us is safest and what those coming to treatment set as a goal. As I wrote yesterday, abstinence is also something families prioritise. Despite this, while the evidence is pretty solid that number one is generally achieved, there is less to convince us that the next bit is happening.

To lay my cards on the table, I am committed to harm reduction and have prescribed (and do prescribe) MAT in community and residential settings. I also believe in the capacity of many with opioid use disorder to move on to long term abstinent recovery with appropriate treatment and safeguards. That’s why this kind of research is of interest to me.

The paper outlines that retention in ORT is not great, with just over half of patients sticking with methadone and fewer with Suboxone. Jason Schwarz has written before about disappointing retention rates for both methadone and buprenorphine in many research studies. It may be that long-acting injectable buprenorphine will improve this.

Despite poor retention in the Berlin study, they did report growing numbers of people on ORT. It appears though they are people who are not moving on to abstinence; I suppose the ones the press call ‘parked’ on methadone. So the authors ask: “Why is this?”

The researchers speculated that it could be because:

- fewer people are dying;

- that people don’t want to move on because of the benefits they are getting;

- that detox is generally unsuccessful, or

- that what staff think patients want is not what patients actually want.

To test this out they sent out an anonymous questionnaire to treatment settings in Berlin. Forty-six staff (more than half doctors and the rest nurses and admin) and 986 patients completed it. They focussed on whether ORT was of benefit, whether it was perceived as harder to detox from than heroin and how strongly patients wished to come off of ORT compared to how strongly staff thought their patients wanted to come off.

What did they find?

- Both patients and staff thought ORT helped physical and mental health.Beneficial effects of ORT on the ability to work and on crime were rated significantly higher by patients compared to staff.

- Staff and patients agreed that coming off ORT was hard. Patients thought it harder than coming off heroin.

- Patients wanted to eventually come off ORT at a significantly higher rate than staff estimated.

About half of the patients in the sample were over 40 years old and more than one in ten were over 50 with almost three quarters of patients struggling with opiate dependency for more than ten years. Only ten percent had never tried to detox, suggesting high failure rates which may have reinforced the belief that ORT was hard to more on from.

There was no differentiation made between methadone and buprenorphine. The study didn’t look at whether evidence based support and treatment was given at the time of the detox.

The thing that intrigues me the most was the:

striking discrepancy between the patients’ and staff members’ assessment of the patients’ desire to end OMT on the long term. The large majority of patients report the desire to end OMT on the long term, whereas only a minority of staff members believe that their patients might really have such a desire

David Best found much the same thing (in aspirational terms) in a sample of drugs workers in the UK. They believed only 7% of their clients would eventually recover when long term recovery rates are actually much higher. The DORIS study in Scotland angered some professionals when it reported that many patients entering treatment wanted only to become drug-free; something treatment was not delivering.

A study in Leeds found that service users, their families and friends placed “considerable weight” on abstinence and “ways of maintaining abstinence”. It’s clear to me that where there is such a mismatch, when the bar is set so low and when there is little hope pervading treatment settings, then it’s no wonder that so few actually do move on.

By the conclusion the authors find themselves at odds with the assertion at the start of the paper (that ORT has an aim of ‘abstinence from opioids’.) Here’s what they say (my emphasis):

Finally, detoxification of OMT is not the prime objective of treatment. The prime objective of treatment is continued physiological and social stabilization. As yet, there is no validated medical cure for opioid addiction. Until a curative medication or a safe curative procedure is developed, many of the patients may have to remain in treatment for the duration of their lives to avoid relapses, increased criminality, subsequent overdoses, and death during the post treatment period.

So the solution to the mismatch between the low expectation of staff and the higher expectation of patients is to lower the expectation of patients to that of staff? Well that’s one way of looking at it.

We still have the problem that lifelong ORT, whatever its evidenced benefits, is not what people want and that, in fact, many do move out of opiate dependence into long term abstinent recovery. These people would no doubt agree that methadone did make things better, but for them it was not the final destination.

What would it be like if the dearth of recovery-oriented research in the UK was addressed, if we focused on what works rather than what doesn’t? If all we do is compare ORT with stand-alone detox, then we are always going to see poor outcomes. What is the impact of abstinence-focussed treatment on injecting and drug deaths in Scotland? We don’t know.

Another more enlightened and rewarding approach might be to move away from thinking about a drug or a medical ‘cure’ as being the solution to addiction and looking to introduce recovery-oriented systems of care using strongly evidence-based psychosocial interventions and treatment where those interventions are of adequate intensity and duration. Linking people to recovery communities is protective with regards to relapse, but there is little evidence that it is happening to the extent that it might.

In the UK we have recovery-oriented drugs policies which aim for rapid access to treatment with a variety of approaches on offer. Reducing harms has to be first priority, but is it enough in itself? Clearly we need to listen to what patients and their families want from treatment and be honest about what’s going to help them get there.

The answer is not to lay out the choice as ‘ORT or abstinence’ but to see how we use ORT as a tool and to find ways of bridging people out of treatment and reliance on services into recovery if this is their goal. We can put robust structures in place to minimise harm and have rapid access back into medication assisted treatment if it is needed.

Some may indeed choose to remain in treatment in the long term, but we need to set the bar high and be positive about patients’ ability to move on in a treatment system that’s joined up and meets the needs and goals of patients at various points in the recovery journey.

Professionals should spend time with people in recovery to engender hope in themselves. The ethos and structure of systems of care need to change so that abstinent recovery becomes part of the norm and range of options instead of a wild aspirational status that we think is too dangerous and we actually believe most people will never achieve.

Now how do we make that happen?

Footnote: this is an updated version of a previously published blog.

Mike Hooper proudly served his country in the US Army, but was secretly battling a substance use disorder. Upon his discharge from the military, he sought help from the VA office. There he found SMART Recovery. Today, Mike is the SMART State Outreach Director for Ohio and co-facilitator of the new Veterans and First Responders meeting.

View the full video on our YouTube channel

Listen to Mike Hooper’s Podcast

Learn more about becoming a SMART volunteer

Learn more about the Veterans programs

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.