The first major effort to define recovery in America was in 2007, when the Betty Ford Foundation, now the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation published What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. The paper noted that “recovery is a voluntarily maintained lifestyle composed characterized by sobriety, personal health, and citizenship.” Our understanding of the continuum of substance use, from social use without consequence to addiction has improved significantly in the years since it was first published. A myriad of recovery definitions of recovery have been penned as our understanding of the dynamics in play have improved. As a house divided, none have achieved broad consensus.

Copious amounts of ink have been spilled in academia over the years on defining recovery. The defining of recovery has become a cottage industry, everyone seems to have a different one, none of which broadly resonates across our society. This is a matter of deep contention an increasingly a front in our larger culture war. It is a formidable barrier to forward progress. As Bill White noted in Addiction Recovery: Its Definition and Conceptual Boundaries has consistently failed to achieve consensus, is not just an academic question, but it has economic and political context as industries have formed around harm reduction, addiction prevention, treatment and recovery support. We are awash in definitions that have become increasingly broad and used to define any positive outcome for any person experiencing any form of substance misuse. How you define recovery is almost like a Rorschach test on where you stand in respect to your experience of substance misuse and your orientation to any of the related fields of interest.

Science is revealing that resolving a substance use condition is quite nuanced, even as we increasingly lump all of what can occur in respect to healing under the term recovery. This last point will inevitably create additional challenges in how the general public understands substance misuse and its spectrum of resolution. It may serve us well as this juncture to assigning the spectrum of resolution of varying severity or forms of substance misuse distinct terms in order to assist society in understanding the complex dynamics in play across the continuum of healing. A taxonomy of healing.

NIDA had taken an all-encompassing strategy to define all resolution under the term recovery. In its 2022 to 2026 Strategic Plan, NIDA notes that “Recovery from SUDs means different things to different people. Broadly speaking, it is a process of change through which people improve their health and well-being while abstaining from or lessening their substance use or by switching to less risky drug use. For some, this may mean complete abstinence; for others, recovery could be ceasing problematic drug use, developing effective coping strategies, improving physical and mental health, or experiencing some combination of those or other outcomes.”

The NIDA strategic plan is reflective of our current scientific understanding of the continuum of substance use from non-harmful use, through misuse to severe substance dependence. Severe SUD typically leads to loss of control. For those of us whom who experience it, refraining from all use is often indicated. It is not an uncommon experience for persons on the far end of the spectrum to die attempting to moderate their use in the way that a person with a less severe form or one in an earlier stage of progression can manage with moderation efforts. It is important to remember that point.

NIDAs approach is consistent with the most recent definition of recovery from NIAAA. “Recovery is a process through which an individual pursues both remission from AUD and cessation from heavy drinking. Recovery can also be considered an outcome such that an individual may be considered ‘recovered’ if both remission from AUD and cessation from heavy drinking are achieved and maintained over time. For those experiencing alcohol-related functional impairment and other adverse consequences, recovery is often marked by the fulfillment of basic needs, enhancements in social support and spirituality, and improvements in physical and mental health, quality of life, and other dimensions of well-being. Continued improvement in these domains may, in turn, promote sustained recovery.” It includes cessation of heavy drinking as characterized by drinking no more than 14 drinks a week as recovery if sustained over 90 days.

My own views on recovery have certainly evolved, although it also true that the first definition of recovery from Betty Ford is the one that resonates the most deeply with me. I am grateful for this space at Recovery Review for those sharing views and challenging our collective thinking. In Mid-December, Brian Coon posted How Helpful is the 2022 Definition of Recovery from the NIAAA? His overall perspective is favorable. He noted that he liked it for several reasons including that it seems to hold space for harm reduction approaches, incrementalism of long/slow change, and addressing people at different stages of change, and of treatment, on a per-problem basis.

A few days later, Jason Schwartz posted More on the NIAAA definition of recovery. His post links this NIAAA Webinar: Using New Definitions and Tools to Support Alcohol Recovery. Jason notes that he has some dissonance with it and describes how recovery has cultural and well as scientific connotations and that people in recovery can and do develop a recovery identity. He asks if it make sense to develop research definitions that create discord with cultural understandings (even if their boundaries are poorly defined). He explores the discord and considers how research and cultural understandings interact and influence each other when there are such rifts.

This dissonance plays out with vitriol in the harm reduction, treatment, and recovery support space. People calling those who have pursued full abstinence in order to not die from addiction as elitists. On another “side” there are still far too many people in abstinence-based recovery who continue to view any properly taken medication as inconsistent with recovery despite all the evidence to the contrary. Our lack of consensus-based terms to describe the resolution of substance use conditions across a continuum of severity and type are at the heart of much of the conflict.

Drug policy, including the defining of recovery is now a front in our larger culture wars. Jason highlights this in his recent piece Liberalism? Or libertarianism? There has been public backlash to these approaches. Under the NIDA definition, a person using a clean needle to use drugs may be considered to be in recovery as they are reducing the risk of infection. While polices that seek to keep people alive and improve their overall health are certainly evidenced based and a good thing to be embraced, I don’t think our society is at the point in which using a clean needle is equivalent to the types of systemic changes people in more recognizable recovery undergo. Low threshold engagement and harm reduction efforts make sense and should be expanded but lumping it all under the term recovery is a bridge to far.

From a 50,000-foot level, this is causing our collective interests a great deal of harm. We can ill afford the polarization of the stakeholder groups interested in saving more lives from the impact of substance use across our communities. We need broad consensus that bridge the gap between the scientific and society. We must bridge science and culture to move forward with a nuanced taxonomy that describe reduced risk stages and forms of substance use resolution.

Lumping all change under the term recovery obscures our capacity to understand the continuum of SUD resolution. The term was historically embraced to express the experience of persons with the most severe forms of substance use. A term indelibly linked to the kind of lifestyle that hundreds of thousands of people like me with the most severe form of substance use experience, which includes no recreational or misuse of substances as a life sustaining imperative.

How does this differ from an interventional or process of changes people undergo from a less severe form of the condition? What we call things matters and improves our capacity to positively affect change.

From a science perspective:

- How would a more nuanced model of substance misuse resolution inform work done in the field?

- Can we develop more granular understanding of resolving a substance use condition in order to provide better weatherproofing for recovery remission?

- What course of strategies would recommend to a person based on the severity of their presenting condition if we could articulate it better and work to understand individual risk factors and level of recovery capital?

From a cultural perspective:

- What value would a consensus definition of the continuum of substance use and the resolution of a substance use condition have for our whole society?

- How can improved insight and more concise definitions of resolving a substance use condition support better targeting of interventions earlier in problem resolution?

- What can we learn from the past about the collective outcome of all of our infighting?

We should stay consistent with the historic use the term recovery to describe those who have found resolution of a severe form of the condition requires cessation of use and systemic life changes. We can then describe the resolution of less severe forms consistent with both our scientific and broader cultural understanding of what this looks like and under which conditions and for whom moderation or other interventions may be an effective healing strategy.

It is an imperative to develop a conceptual SUD healing framework with broad consensus. To assign the resolution of a substance problems of varying severity and type distinct terms within a taxonomy of healing. It would help us understand the complex dynamics involved in resolving a substance use condition. For policymakers and researchers out there for whom this resonates, perhaps it is time to convene a focus here and take action.

For those of you who may disagree, I hope you continue the dialogue in respectful in open ways in order to assist all of us in developing a conceptual framework that fosters broad consensus and greater public understanding of the complexity of substance use conditions and their resolution.

While challenging, the prize is well worth the effort.

The New York Times published a guest essay this weekend challenging the disease model of addiction.

I’ve read several similar pieces over the years and frequently have the same experience. I agree with most of the writer’s points, but disagree with his conclusions.

Let’s walk through it.

Annual U.S. overdose deaths recently topped 100,000, a record for a single year, and that milestone demonstrates the tragic insufficiency of our current “addiction as disease” paradigm.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

The drug death rate is very troubling and discouraging. If we were to add deaths associated with tobacco and alcohol, it’s much worse.

This strikes me as evidence for the insufficiency of our interventions to prevent and treat addiction, and/or the insufficiency of our systems to deliver those interventions. It does not strike me as evidence that it is not a disease. If COVID, type 2 diabetes, or asthma are associated with a large death toll, is that evidence that they are not diseases?

Thinking of addiction as a disease might simply imply that medicine can help, but disease language also oversimplifies the story and leads to the view that medical science is the single best framework for understanding addiction. Addiction becomes an individual problem, reduced to the level of biology alone. This narrows the view of a complex problem that requires community support and healing.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

This portion starts to illuminate the disagreement between me and the writer.

He’s concerned that too many people believe biology and medicine are the only frames we need. Further, he’s troubled that this might lead to interventions that target only individuals and omit social interventions.

I share those concerns.

However, I don’t see this as reason to doubt the disease model.

I believe asthma is a disease and environmental interventions are important. In the case of asthma, climate change might be a reasonable target for intervention. I believe type 2 diabetes is a disease and community-level interventions are critical. COVID is a disease and individually targeted interventions are clearly an insufficient response. I also believe depression is a disease and interventions targeting social support will be essential for many patients.

I also believe that behavioral interventions are essential for responding to all of these diseases and many others.

My experiences and those of my patients seem more in line with how 16th- and 17th-century writers described addiction: a disordered choice, decisions gone awry.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

If we view addiction as a brain disease, I don’t see how disordered choice is incompatible. Choice occurs in the brain. One could argue that other diseases involving the brain (depression, bipolar, schizophrenia, OCD, etc.) also result in disordered choice.

[Benjamin Rush] was famous for describing habitual drunkenness as a chronic and relapsing disease. However, Rush argued medicine could help only in part; he recognized that social and economic policies were central to the problem.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

This is a better understanding. It might be worth asking how to restore and protect that broader understanding.

The author points to a history of using the disease model (or beliefs associated with the disease model) in ways that are racist. All of this history is true and important, but it doesn’t really say anything about whether addiction is a disease. COVID was racialized, particularly early in the pandemic, but this is not grounds for reclassification of COVID.

The author continues addressing social justice issues in responses to the drug problem and raises another important consideration:

Not all drug problems are problems of addiction, and drug problems are strongly influenced by health inequities and injustice, like a lack of access to meaningful work, unstable housing and outright oppression. The disease notion, however, obscures those facts and narrows our view to counterproductive criminal responses, like harsh prohibitionist crackdowns.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

I see how a narrow medical/biological framing of disease can obscure the roles of inequities, injustices, and oppression. I also see how blindness to those factors could lead to criminalization. However, a disease model, at worst, cuts both ways. A deterministic view may contribute to prohibition and criminalization, but a model that locates addiction, not in the drug, but in the interaction between the brains of certain users and the drug, might push in the other direction.

The important point he raises here is that “not all drug problems are problems of addiction”. To be sure, addiction constitutes a relatively small fraction of all drug problems. It would be both incorrect and harmful to classify non-addiction drug problems as a disease. This is a critical point that, to me, reinforces the need to clarify the boundaries of addiction and distinguish it from other drug problems that are not a disease.

In contrast, today, descriptions of “brain disease” imply that people have no capacity for choice or self-control. This strategy is meant to evoke compassion, but it can backfire.

Is Addiction Really a Disease? by Carl Erik Fisher

No thoughtful expert would suggest that people with addiction have no capacity for choice or self-control. However, the author previously stated that a “disordered choice” model resonated with his experience, which fits well with the impaired control described in definitions of addiction that frame it as a disease.

The public responses that the chronic brain disease model evokes are complicated. (It may evoke less blame but more pessimism.) It seems to me that basing its designation on public reactions is the tail wagging the dog, and that unstable, conflicting messages probably contribute to pessimism and stigma. If that’s true, the best strategy is to just describe it accurately and focus on other targets for stigma reduction.

The author closes with reflections on the incompleteness of the disease model.

I am in full agreement that a narrow medical/biological disease model is incomplete, inadequate, and will lead us in the wrong direction with respect to prevention, treatment, and policy. The author is a physician and have a lot of respect for a professional that seems to be saying that his discipline can only hope to be a part of the solution to the problem.

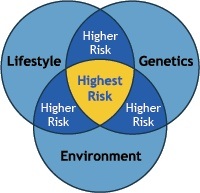

However, I don’t believe the problem here is that “disease” is the wrong category for addiction. The problem is that too many people think of disease in narrow medical/biological terms. This was addressed in the landmark 2000 article, Drug Dependence, a Chronic Medical Illness, which argued that drug dependence is comparable to type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and asthma when considering the roles of genetic heritability, personal choice, and environmental factors, as well the etiology and course of all of these disorders. Chronic diseases are generally complex in their etiology and in what’s required to effectively treat and manage them. The kinds of complexity present in addiction are more the norm for chronic diseases rather than the exception.

Recent years have seen increased interest in social determinants of health (SDOH), which serve the purpose of filling in the rest of the picture in terms of etiology and treatments/interventions.

Surprisingly, even genetic counseling offers insight into social and environmental factors that influence the onset and course of heritable illnesses.

So… is it misleading to call addiction a disease? Only if your understanding of disease is too narrow to allow for the complexity of chronic diseases and social determinants of health.

I think the solution is that we get better at talking about diseases and their complexity, rather than reclassify addiction because it’s too complex.

Someone relatively new to the substance use disorder area asked me recently why I thought there was so much division and hostility in the addiction and recovery field, compared to other parts of health and social care. Do we really have more conflict than in some other healthcare areas? There are strongly held positions which seem impossible to reconcile in all areas of life. Is addiction policy, advocacy, treatment, support and recovery any different?

After nearly 20 years of working exclusively in this field, my conclusion is that it probably is different. This is certainly something to be curious about. At the outset I want to be clear: I also believe that there is plenty of harmony too – much that binds us together and some great examples of collaboration in the interests of the people and families we are trying to help.

Some of the division is between harm reduction and recovery or, more precisely, around harm reduction, medication assisted treatment, and abstinent recovery. A great number of people have called this out as a false division, urging us toward a broad range of responses centred on people’s needs in the here and now and guided both by evidence and individuals’ rights to choose the recovery path that is right for them. Sometimes those voices are drowned out by polarising dissent.

Every week I hear strongly held perspectives on one side or the other of these fissures. Sometimes the antagonism to a particular approach is more subtle and we see exclusion and attitudinal barriers rather than overt criticism. At times we can tell more about an organisation’s or individual’s approach by what they don’t say.

For instance, in some circles the words ‘recovery’ and ‘abstinence’ are rarely seen or mentioned despite being important to some people trying to resolve their substance use problems. Similarly, other people consider opioid substitution therapy to be simply replacing one addiction with another, despite compelling evidence of reduction of harms. Pressure can be put on people to detox without adequate preparation, supervision or supports in place creating avoidable risks.

The question about the vigorous level of debate and fiercely held opinion we experience in the domains of addiction, treatment and recovery is a good one without a simple answer. I’ve been thinking about this since and here is my tuppence worth.

We are passionate

Many of us who work in addiction treatment are impassioned about substance use disorders and the responses we have to them. This passion is driven by personal and professional experience, by hope and as a response to the grim drug and alcohol deaths we see. Such passion drives beliefs and actions and can lead to progress and improvement in the lives of individuals. However, sometimes passion can be enacted as anger or arrogance. It can spill over into wrath or rage. On occasion, it can disguise fear.

These experiences which drive passion can be self-defeating or limiting. If you have made an abstinent recovery aided by 12-step fellowships, you may come to believe that this is the only way to recover – though, to be fair, many people in mutual aid groups will readily acknowledge that there are multiple pathways to recovery. Similarly, if you are not seeing evidence of people moving on to abstinent recovery and of them leaving treatment settings, you may believe that people do not recover or that it is much too dangerous to support such a path.

Then there is the danger of zealotry, driven by passion or fear – a blinkered approach which will not, or cannot see that we need a broad and welcoming church – a place that celebrates diverse approaches and pathways. When contempt for others creeps in, often unbidden, we diminish our effectiveness and authenticity.

This week in a newspaper I read an article where one treatment service explicitly undermined others, using misleading words. The effect was to distance the reader from some of the other good points made. The unintended consequence was disconnection, further division and a lack of positive impact. While we don’t need uniformity and we need to have the capacity to call out wrongs, we also need mutual respect. It’s a good value to hold close.

You can have no influence over those for whom you have underlying contempt.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

My fellow blogger Bill Stauffer recently noted that social media may not help us here. We connect with others who hold the same views as us and end up with confirmation bias or we get swept up in the wave of righteous indignation and then write things that are disrespectful, rude, or even threatening.

As a relative newcomer to Twitter, I was naïve enough to be shocked initially by some responses to my early posts and to what I saw as the reasonable perspectives of others. I follow many whose views `I do not agree with, but read what they post with interest, however I don’t tolerate abuse. We behave differently online than we do in person and indeed, social media may actually harm our emotional health. I am grateful for the mute and block buttons – wonderful inventions.

We are concerned

If we see our clients/patients dying of drug and alcohol-related causes when they do move out of treatment, we may think that it is too risky for anyone ever to move on. For those of us who work in addiction treatment and support, hearing about overdose and death is a chilling, upsetting and unwelcome part of the job. But being excessively worried and anxious about the safety of those we are trying to support can lead to unhelpful consequences.

Without adequate supervision and support we can begin to live with unrelenting and harmful levels of concern. Then we can begin to get burnt out or develop dysfunctional thinking and behaviour.

Concerns about detox and abstinent recovery need to be addressed, as do those around MAT and harm reduction. Myths need to be put to bed though. Reassuringly, there are plenty of practitioners who have reconciled those concerns in a way that allows them to work passionately across all areas, mitigating risks but not in a way that stymies the capacity of people to achieve their goals. I am in awe of some of them.

We have limited resources.

When funding is tight and demand is high or services are threatened, we can reflexively respond in defensive ways, or even attack others’ services. I’ve certainly experienced that in the past – people who are normally supportive behave in ways that are difficult to understand and everybody feels hurt and upset.

When resources are limited, you get people fighting their corner, but this can spill over into arguments about which services should be limited, have resources removed or be shut down. Think residential rehab for instance – often cited as ‘not evidence based’ by those who put their faith wholly in medical models, they can be seen as low hanging fruit when money dries up. I’ve experienced this more than once.

We get disenfranchised.

The reason we have a surge in advocacy and support for people with alcohol and drug problems is that they have not felt represented by the services set up to help them and have not felt that those services have met their needs. They have not had a voice. Or just as bad, when that voice speaks up, it is ignored, dismissed or treated with contempt. Perhaps, worst of all, individuals can sometimes be given a tokenistic place at the table – present but powerless. While huge power disparities persist, it is always difficult for lived experience to have any impact on policy and the shape of services.

Now when voices are beginning to be heard – and in Scotland those voices are likely to become more powerful and influential through the forthcoming National Collaborative – they can feel threatening to the establishment. Yes, we have our evidence that we base our treatment offer on, but now we have new evidence of a bit of a mismatch between what we have on offer and what individuals and their families want from treatment. We have a distance to go to achieve balance.

There are those who would shut those voices down, but the likelihood is that, in terms of visibility and volume, in the future lived and living experience is not going anywhere but up.

I will ensure that local panels of people with lived and living experience are involved in all local decision making, and that a national forum or collaborative is in place to better inform our national mission.

Angela Constance, Drugs Policy Minister

We lack the breadth of experience

Years ago, a colleague who had worked in the field for years told me he’d never met anyone in long term recovery from heroin addiction. At that point, I’d met hundreds, so we could agree that we’d had very different experiences – poles apart. If professionals don’t get to see sustained abstinent recovery, instead seeing people remaining in treatment for many years or indeed experiencing too many deaths of clients or patients then of course it’s going to feel pretty risky to support people to the goal of moving out of services all together.

Equally, although I now work in residential rehab, working in harm reduction and medication assisted treatment settings in the community has helped me see the need for a broad spectrum of approaches to help individuals achieve their goals. Recovery is dynamic and non-linear and needs flexible and wide-ranging approaches to support it.

We are all a little prone to suffering from the Dunning Kruger effect, a cognitive bias where we think we have more knowledge and skills than we actually do on an issue. If all practitioners got to spend some time in different settings (from injecting equipment provision and wound care through to community and residential services and get a robust introduction to community recovery and support resources) then we’d perhaps seen more harmony and mutual respect.

We don’t always know ourselves

We go into caring roles for a variety of reasons and not all those reasons are apparent to us as individuals or to others. For some of us, growing up with addiction in our families can lead to a healthy desire to help other families. For others, unresolved wounds and conflicts from early life can hamper such efforts. We may not have tended to those early wounds or even be aware that they are still tender and are influencing our behaviour in the here and now. Other formative experiences can lead to a variety of motivations.

Some of us have a desire to rescue, we might be subject to countertransference, or we can collude. I have seen harm come to individuals on occasions, thankfully rare, where over-involved practitioners with poor boundaries conspire with their clients against the very services that are most likely to be able to help them.

When dealing with people, remember you are not dealing with creatures of logic, but with creatures of emotion, creatures bristling with prejudice, and motivated by pride and vanity.

Dale Carnegie

Some of us feel threatened when those who have depended on us for help want to become independent and move on. We may resist routes that can lead people to ‘abandon’ us. I have heard so much resistance to mutual aid, for instance, across my entire career in addictions – way beyond what is logical or reasonable – that it makes me wonder just what it is driving it. Could the lack of tolerance and acceptance be in part the fear of being divested of our charges, the pain of potential loss?

I’ve heard it said that without self-care we are prone to absorbing some of the disordered behaviours and thinking that can impair our clients – in a sense soaking up some of the pathology of addiction. Good supervision can increase insight and help to prevent this, but where supervision is not available or not utilised, disharmony and friction can develop and spread. Organisations and individuals who have a tendency to blanket-blame and shame others (others for the most part who are genuinely doing the best they can) may be suffering from this. Difficult people and difficult cultures exist, and we need to find ways to deal with them, exhausting though that may be.

Just because you’re dealing with difficult people, does not mean that you must become like them.

David Leddick

The work is challenging

Supporting people with substance use problems can be rewarding, but it can also be challenging. The high rates of death for those with alcohol and other drug problems are distressing. Disclosure of trauma and adverse childhood experiences can be difficult to hear and leave us lingering anxiety and disquiet. Sadness, anguish and grief can steal in and set up permanent home.

We can continue working but begin to detach or distance to the point where we become less empathic and compassionate. When we struggle like this, we may be less tolerant or even become cynical. Our relationships with others can then suffer and we take on a negative mantle but fail to recognise what’s happening. High sickness rates and excessive turnover in teams can be a reflection of this.

The way forward

And the solution to the bellicosity? You’ll need a smarter person than me to give a definitive answer to this.Addressing similar issues, Bill Stauffer quotes something that resonates with me ‘we no longer unite on things we agree on, we come together focused on things we hate’ – while this is not my whole experience, I am afraid that there is a kernel of truth here.

Love difficult people. You are one of them.

Bob Goff

A fundamental principle to moving forward is first taking a look at the part we play in this ourselves. What’s my thinking and behaviour like?.

We must examine our own flaws and blind spots in order to understand our common ground.

Bill Stauffer

Further, were we to focus on common ground, perhaps we could bring healing and consensus. On my best days I try to find that middle way, but as I say, I’m passionate too, my opinions are forged in a crucible of fire, I react to what I understand as others’ unreasonable positions, and I have my own blind spots. Sometimes I sit comfortably in my own echo chamber. There is a real risk that we lose sight of the people who we are trying to help as we pursue our own agendas.

The reason I’m mostly writing in first person plural (‘we’) is that I recognise many of these tendencies and vulnerabilities in myself. I get passionate, frustrated, angry and hurt, but when I take ownership of these reactions rather than blaming others, it gets easier for me to move forward. If I ever get good at this, I’ll let you know.

Show respect even to people that don’t deserve it; not as a reflection of their character, but as a reflection of yours.

Dave Willis

I have learned though that I don’t have to show up to every argument I’m invited to. More positively, I have found that when you bring people together, create connection and offer a safe space for dialogue, listening and exchange of ideas, you build bridges instead of barricades. There are values that need to underpin this approach – curiosity instead of condemnation, compassion instead of conceit, kindness, respect, willingness to learn, and a genuine desire to relate to one another.

You have brains in your head. You have feet in your shoes. You can steer yourself, any direction you choose.

Dr. Suess

When those new to the addiction field question how unhealthy it seems, we all ought to sit up and take notice. We are responsible for the culture we have created. If that is a culture of conflict, we need to attend to it. Leaders have a particular responsibility here – we ought to be held to a high standard of behaviour and professionalism. That need not make us impotent, but rather be mindful of the power that we hold and how we use it. Change starts with ourselves.

There’s one more thing – another value – that is missing when there is turmoil. That value is humility. It’s not reasonable to expect that we all agree on everything all the time. This would be a disaster – we need to feel discomfort, disagreement and passion; these can be potent drivers for positive change, but perhaps a little bit of ‘I could be wrong and others right’ would go a long way to pour oil on troubled waters.

Adam Grant, the organisational psychologist, nails it when he writes: ‘At the root of our polarisation problem is a deficit of intellectual humility’.

I’ll leave you with the same question that I’m holding on to. What can I/you do to heal division and help our field to be more effective and a healthier place to practise? How do we hold our convictions passionately, be authentic in challenging poor practice and behaviours, yet foster consensus and harmony? I’m really interested to hear your thoughts.

Continue the (respectful!) discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

Therapeutic nihilism

“None of them will ever get better”, the addiction doctor said to me of her patients, “As soon as you accept that, this job gets easier.”

This caution was given to me in a packed MAT (medication assisted treatment) clinic during my visit to a different city from the one I work in now. This was many years ago and I was attempting to get an understanding of how their services worked. I don’t know exactly what was going on for that doctor, but it wasn’t good. (I surmise burnout, systemic issues, lack of resources and little experience of seeing recovery happen).

Admittedly, a part of me recognised an echo of the sentiment. I’d worked for many years in inner-city general practice and back then, to be honest, I did not hold out as much hope as I might have for my patients who had serious substance-use disorders. After all, the evidence in front of my eyes suggested intractable problems. All of that changed when I began to connect with people in recovery and started to understand the factors that promote it.

Palliation or something better?

I don’t think my colleague’s perspective was (or is now) the predominant view, but by no means is it unique either. An addiction specialist has fairly recently urged us to accept that some ‘do not have the luxury of recovery’, seeing it as ‘a convenient concept, but an unobtainable reality for many people who use drugs’, who are really in ‘palliative care’. I struggle with this perspective. Some would say it’s realistic. I think it’s pessimistic.

Of course, there are people whose chances of resolving their problems and going on to achieve their goals remain low despite support, but who gets to choose who gets ‘palliation’ and who gets something better? We don’t start out with palliation as a goal of cancer treatment; why should addiction treatment be any different? If our treatment offer is focussed on palliation and only the few – the worthy and fortunate – get to go further, we are letting people down badly. Professor David Best has pointed out that this sort of therapeutic pessimism is a major barrier to the effective implementation of a recovery model.

My assessment in my visit to that MAT clinic was that I could not work in a service where views like that, for whatever reason, had become acceptable and explicit. However, rather than be defeated, I found instead that this provoked an energy within me to try to make a difference. That one incident, perhaps more than anything else (save my own experience of treatment and recovery), drove me to set up the service I now work in.

The clinical fallacy

While therapeutic pessimism undoubtedly exists, I am buoyed up by my past experience of working in teams in community settings where expectation of what is possible is much higher. I can think of many colleagues who set the bar high every day in their work, even when they are working in demanding circumstances.

While despairing and cynical views are not the norm, it is apparent though, for whatever reason, that some working in the field don’t hold out as much hope as they might. I’ve heard enough reports from individuals who feel they were discouraged or blocked from moving on towards their goals to know that it happens too often.

This nihilistic view of the potential of individuals to resolve their problems and move towards their goals can be explained to some degree by something Michael Gossop called ‘the clinical fallacy’. This is the situation in which the clinician sees all of the challenging presentations and relapses, while the people who resolve their problems move out of treatment and are not seen again.

The clinician is confronted continually by their failures and denied the benefit of seeing their successes.

Michael Gossop, 2007

This may explain findings from elsewhere which show that we professionals working with people who have substance use disorders consistently underestimate what our clients/patients are capable of. This is important. The clients of clinicians who are more positive do better[1] and conversely negative or ambivalent attitudes in professionals are linked to higher risk of relapse.

Professor Best, interviewed by William White in 2012, referred to work he’d done in the UK, scoping out the aspirations of addiction workers for their clients. He had asked them to estimate what percentage of the people; they were working with would eventually recover. The average answer was 7%. Evidence actually suggests that over time most individuals are likely to recover. However, if I believe your chances of recovery are only 7%, then I’m instantly holding you back because of my own beliefs and behaviours – conscious and unconscious. My bar is set way too low.

An Australian study found that practitioners there were more optimistic believing that a third of people with a lifetime substance dependence would eventually recover. But this is still an underestimate.

In general, it is fair to say that SUs [service users] look for tough criteria to define ‘being better’ – perhaps tougher than their practitioners.

Thurgood and colleagues, 2014

Raising the bar

Eric Strain picked up this theme of aiming too low in a recent editorial in the journal Alcohol and Drug Dependence when he wrote:

The substance abuse field in both its research as well as treatment efforts is not giving due consideration to flourishing. We need to renew our efforts to give meaning and purpose to the lives of patients.

Eric Strain,

Saving lives and reducing harms rightly need to be our first concerns, but is there a danger that we stop right there because we see the risks of our patients or clients going further as being too high? This week I was talking to an experienced addiction psychiatrist, now retired. He told me that early in his career he gave up trying to predict who was going to do well and who was not. He’d seen people, ostensibly with little going for them, get better from what looked like intractable problems. He’d seen others with a great deal of recovery capital die from addiction, despite the best efforts of family and professionals to support them. It’s hard to make predictions perhaps, but not too hard to hold out hope for everyone.

The necessity of hope

There are actually reasons to be more optimistic anyway. As I say, long term follow-up studies and retrospective studies of people in established recovery suggest that most people can expect long term resolution of their symptoms although this can take some years and several attempts during which we need to focus on keeping things as accessible, supported, and safe as possible, underpinned at all times by hope that things can and will get better.

So what of hope? Hope can be described as an emotion, a cognitive process or a positive anticipation which helps to motivate goal-oriented behaviour. However we define it, it is essential for recovery from substance use disorder, yet it features little in textbooks, guidelines and academic studies.

The patchy availability of hope in ourselves, our services and our service users does need to be addressed. Hope is a catalyst for moving forward. Academics have found that positive expectancies, like hope, predicted higher levels of resilience against post-traumatic stress symptoms. Other researchers have identified the critical role of hope in terms of survival.

The inclusion of hope in clinical practice shows considerable promise. Individual, group, and family therapy interventions that incorporate hope theory have been found to reduce symptomology and mediate recovery from various psychological and psychosocial conditions

Gutierrez & colleagues, 2020

It is apparent that hope is a necessary ingredient, not only for patients/clients to progress, but for professionals too if we want to be effective in supporting individuals towards their aspirations. I’m not suggesting we come at this with an unrealistic Pollyanna bent. Without manageable caseloads, support from colleagues, good clinical supervision and adequate resources – including joined-up care – compassion fatigue can set in and the therapeutic relationship can suffer. Hope, though vital, can ebb away.

“We must address issues around staff burnout, which I suggest is related to repeated exposure to client relapses without parallel exposure to clients in long-term recovery.” David Best, 2012

Prof David Best

The introduction of hope

In that conversation with William White, David Best encourages us to ‘inspire belief’ through a variety of interventions::

“The interesting issue for me is much less about what particular therapies and modalities we offer and more about whether we can inspire belief that recovery is possible, establish a partnership between the client and the worker to facilitate that change, mobilise recovery supports within the client’s natural environment, and link the client to those community resources.

We also need to locate recovery within a developmental perspective that recognises the lengthy (and non-linear) journey that most people experience in recovery. This means there are plenty of opportunities for a diverse array of interventions and also that people will evolve in their needs and their resources as the recovery journey progresses.’

Lived experience and hope

Structurally, the goal must be to create recovery-oriented systems of care, but within our existing services, there is a straightforward way to infuse hope. We can do that by embracing lived experience and introducing it into what are normally professional settings. Connecting those we work with to others in recovery stimulates aspiration. It’s true that some professionals are resistant to this concept, but people with lived experience can be involved in treatment settings, acting as role models and beacons of hope to everybody’s advantage – staff and patients. They can also bridge the gap between treatment and recovery communities.

In a local evaluation of a peer support model introduced into a harm reduction service, benefits to the service users were apparent, with greater levels of engagement and a high approval rating of the intervention. What was unexpected though was the benefit to members of the staff team. Because they normally worked with people at a much earlier stage on the recovery journey, the staff were not used to seeing people who had moved on from their problems. That experience of working alongside people who self-identified as being ‘in recovery’ changed the beliefs of the team, raising expectation and hope.

In a study[2] published this month which looked at the feasibility, accessibility and acceptability of peer navigators in roles that aimed to reduce harm and promote recovery (wellbeing, quality of life and social functioning), the researchers added to the growing evidence base that peers with lived experience can positively influence not only the reduction of harm, but also improvements in quality of life through various mechanisms including role-modelling.

Many participants also described less tangible but nevertheless important changes, including increased confidence and hope.

Parkes and colleagues, 2022

This was not all plain sailing, but staff noted how the peer navigators were able to spot things that staff didn’t, had tenacity with clients and could engage more ‘chaotic’ or ‘hard to reach’ clients.

What’s lovely about this open-access study is how easily the lessons can be adopted into practice. There are issues to be tackled and more work needs to be done on capturing outcomes, but this has the opportunity for us to tackle therapeutic nihilism within ourselves and within our services.

Recovery champions can convey the possibility that things can be different and offer living proof of that difference in their own lives.

Prof David Best

Generating hope

Peers with lived experience don’t just have the potential to introduce hope. Research also suggests that peer contact can help to reduce stigma. Visible recovery is generally inspiring, though some may be threatened by it. There is mostly a contagiousness about it which generates hope. I wonder if my colleague working in that challenging MAT clinic who came to believe that nobody would ever get better would have avoided therapeutic nihilism if she were buoyed up by working daily shoulder to shoulder with those with lived experience.

When we see burnout, despair and therapeutic nihilism we need a compassionate response, but more than this, we need to transform situations where hope has atrophied. Moving to peer support models in every treatment setting is surely an effective way to generate hope, not only in those who use our services, but also in ourselves.

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

[1] Simpson. D., Rowan-Szal, G., Joe, G., Best, D., Day, E., & Campbell, A. (2009). Relating counsellor attributes to client engagement in England. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36, 313–320.

[2] Parkes T, Matheson C, Carver H, Foster R, Budd J, Liddell D, Wallace J, Pauly B, Fotopoulou M, Burley A, Anderson I, Price T, Schofield J, MacLennan G. Assessing the feasibility, acceptability and accessibility of a peer-delivered intervention to reduce harm and improve the well-being of people who experience homelessness with problem substance use: the SHARPS study. Harm Reduct J. 2022 Feb 4;19(1):10.

The Recovery Research Institute recently posted a review of a study examining patient and physician definitions of success for opioid treatment beyond treatment retention.

The Study

The researchers conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with prescribers and patients from 2 family medicine clinics. Interviews were conducted by phone and lasted 20-30 minutes.

Physicians

14 physicians

- All waivered to prescribe buprenorphine.

- Half were faculty and half were residents.

- The faculty had been waivered for an average of 5.7 years and the residents for an average of 1 year.

- All white, 8 female & 6 male.

- They were asked 2 questions in a semi-structured interview about treatment success:

- What do you consider success in your patients receiving MAT?

- In addition to retention in treatment, what else reflects patients doing well?

Patients

18 patients

- Average age was 38 years old.

- 14 white, 2 black, 1 American Indian, 3 Hispanic.

- 8 female, 10 male.

- All were long-term MAT patients, averaging 2.5 years at this clinic (range 1.5–4 years).

- They were asked 2 questions in a semi-structured interview about treatment success:

- What progress have you made in your recovery by being part of our medication-assisted treatment program?

- What does success mean to you with respect to your recovery?

Findings

7 themes

Seven themes emerged from the interviews:

- Staying sober

- Tapering off Buprenorphine

- Taking Steps to Improve Physical and Mental Health

- Improved Psychological Well-being

- Improved Relationships

- Improved Role Functioning (Setting and Meeting Goals)

- Shift in Identity (Decreased Stigma and Shame)

Patient / Prescriber Misalignment?

Of the 7 themes identified, the physician and patient groups shared 5 of the 7 themes, but there were 2 that were only identified by the patient group. Those were themes 2 (tapering off buprenorphine) and 7 (shift in identity).

Regarding tapering off buprenorphine, the paper noted that “Only one physician noted that he hears this goal from many patients”. They did not quantify the number of patients identifying this theme but characterized it as “several”. Interestingly, their desire to taper off buprenorphine was not characterized in a way that communicated ambivalence about using the medication to stabilize and initiate their recovery. Comments included mention that it should happen “eventually” and after stabilization.

I find a couple of things striking here.

First, only one of these physicians (who have been waivered for an average of 5.7 years) reported hearing this goal from many patients. It’s easy to imagine physicians not seeing tapering as an indicator of success, but it’s striking that they report not hearing it from many patients, when the researchers found this sentiment to be prevalent among them. Over that average of 5.7 years, how many patients have these physicians treated? Are patients not communicating this to physicians? If not, why? Are physicians not hearing this from patients? If not, why?

Second, these were patients who’d been in the MAT program for an average of 2.5 years and their comments imply positive feelings about their treatment. I imagine a lot of people would frame this theme as a manifestation of stigma. That is possible, but it isn’t intimated in their responses. In fact, one of the comments in theme 7 (Shift in Identity) describes their treatment helping them feel more like a normal person and changing how they feel about their medication.

It’s interesting that I’m familiar with models of care that don’t involve agonist medications like buprenorphine, and there are millions of American receiving treatment with buprenorphine. What I haven’t seen are pathways for tapering stabilized patients off buprenorphine. One wonders if buprenorphine retention would improve if these patients’ preferences were integrated into treatment models. You could frame retention rates as patients voting with their feet about this preference and it’s important to note that these patient comments indicate that they are in no rush to taper, but would like to eventually. Of course, we also need to keep in mind that these are patients who have been retained for 1.5 to 4 years.

As the X waiver is eliminated, addressing this misalignment seems particularly important.

Image by Vectorportal.com

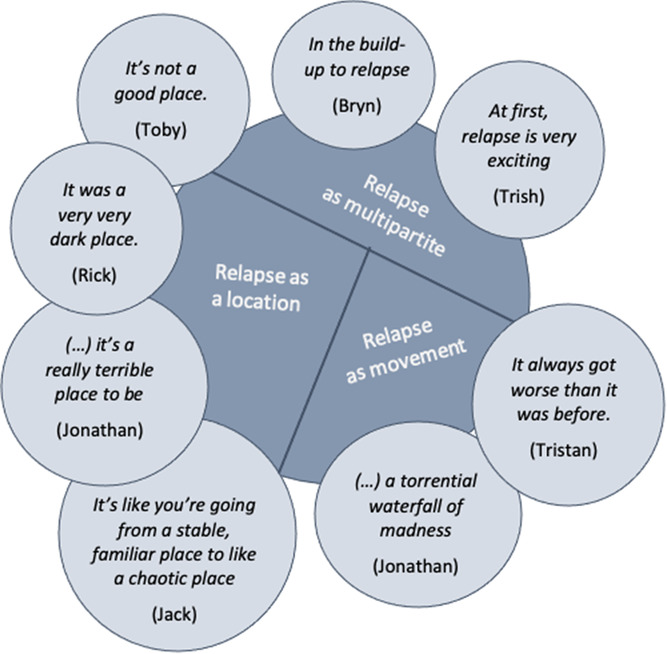

I recently listened to this interview with Maike Klein discussing her qualitative research on the experience of relapse in people with addiction who have experienced repeated relapses.

Here are a few take-aways:

- The experience of relapse is one of self-betrayal — one self being wholly committed to abstinence/recovery and a self at another point in time betraying that commitment.

- A demoralizing element is the loss of trust in self. Knowing that a future self will betray themselves. This is an experience of powerlessness.

- She distinguishes this from self-efficacy which she frames as confidence in oneself to navigate risk environments (external threats to their recovery). Self-mistrust frames the threat as oneself.

- She explored the impact of relapse on clinicians:

- She speaks to trauma associated with witnessing relapses and deaths associated with relapses.

- There is a parallel process between patients and therapists.

- Therapists develop their own experience of self-mistrust and begin to question their own knowledge, skills, and capacities. (They internalize the relapse — I’m not up to the task.)

- Therapists begin to distance themselves emotionally from clients and she describes and experience of clinician powerlessness and implies that the clinician begins to externalize the experience — this is what clients with addiction do… this is addiction.

- This results in emotionally distant therapists. (And, eventually, an emotionally distant system of care.)

- The therapeutic environment becomes untherapeutic.

Why this is noteworthy

We are in a moment where there is so much emphasis on the suffering in addiction as a product of external responses to addiction and relapse. Her work describes the internal consequences of relapse and drug use within addiction. External responses can influence that experience, ameliorating it or making it worse, but that internal suffering exists regardless of external responses.

Her exploration of the parallel process experienced by clinicians (intensified when deaths are experienced) powerfully describes the threats addiction professionals face to maintaining their own wellness, the challenges clinicians and systems face in trying to maintain a hopeful recovery-orientation, and the consequences when that parallel process is not addressed and managed.

Questions

- Is it possible that her description of that parallel process explains some of the current trends in drug policy discussions?

- If so, how does it show up?

- Is it likely that the overdose crisis makes us uniquely vulnerable to playing out that parallel process?

- Does the overdose crisis amplify the consequences of failing to acknowledge and manage parallel process?

1. Hope matters in recovery

I’ve been musing a bit recently on the place of hope in addiction treatment and in recovery journeys. Researchers from the USA[1] identified that hope, although recognised as essential for recovery, was not well researched in terms of how it helps recovery progress. They used validated tools (questionnaires) to assess hope and recovery in 412 people. They found that progressing in recovery reduced relapse risk and that hope had a positive mediating effect.

Behavioural change or life transformation?

The researchers suggest that professionals “Consider adopting a holistic approach to addiction recovery that includes factors associated with wellbeing and human flourishing, as opposed to focusing solely on the managing of behaviours. By helping individuals develop a sense of self efficacy (i.e. mastering my illness), clarifying their values, and fostering feelings of connection and belonging, treatment professionals help individuals reduce the likelihood of relapse.”

They go on to stress how important these elements (self efficacy, values, connectedness) are to people who are new to recovery and how by highlighting these, professionals can strengthen their clients’ journeys toward recovery. Key to this is helping to frame recovery as a whole life transformation and not just a behavioural change. (My emphasis)

That feels like a quantum shift from how we come at things currently.

2. Abstinence goals may be more reliable than moderation goals

People asking for help for their drinking problems have a range of problem severities and a range of goals. Both things can be dynamic. Some folk want to reduce their drinking and others want to stop. Some, with severe physical or mental health consequences related to drinking will die if they continue to drink. When we research outcomes from treatment, we tend to look at outcomes that clinicians think are important and less at whether individuals reach their own goals.

In health terms, there’s a consensus emerging that no level of alcohol intake is completely safe, but for most modest drinkers, the risks are felt to be minimal. However, this is evidently not true for people with severe alcohol use disorders. Research has shown that the best treatment outcomes are achieved when people have set abstinence as an end goal, even if moderating drinking was the goal at the start of treatment. My experience from general practice for those with the most severe alcohol use disorders was that initially some – perhaps most – set moderation as a goal, but over a long period, even with maximum support, they moved towards believing abstinence would be safer.

For the kinds of patients I see seeking residential rehab who are at the far end of the severity scale, all have come to the conclusion that stopping drinking represents the best kind of reduction of harms. Many have tried to reduce or control their drinking over years and found that they could not do it in a sustained fashion.

In research[2] from the United States involving 153 people with alcohol use disorder, researchers explored what was going on in terms of the drinking goals the subjects set themselves daily – whether these varied and whether they were able to reach them. They found that complete abstinence was the commonest goal and the one most likely to be reached compared to those aiming for moderation. Paradoxically, they also found that when a daily goal of not drinking couldn’t be reached, those individuals drank more than those setting moderation goals. Nevertheless, the researchers point out:

Abstinence-based daily goals appear to lead to the greatest reduction in at-risk drinking and quantity of alcohol consumption overall.

Pavadano et al, 2022

They say their findings ‘support the clinical benefit of mapping daily goal setting and strategising for specific circumstances’. Of course, this is something mutual aid groups have been practising for decades.

3. Recovery – pulling is better than pushing

Recently I was asked whether getting bad test results (e.g. evidence of poor liver function from blood tests) could act as a motivator to help cut down drinking in someone with alcohol use disorder. I had to be honest and say that in the patient group I see, almost all of whom have biochemical evidence of livers under attack, this was not the case. I said that motivation for recovery generally has to come from hope that things can get better rather than fears that they will get worse.

It was interesting then to have my own observations bolstered by qualitative research[3] from Derby. David Patton, David Best and Lorna Brown explored the part the pains of recovery (push factors) and the gains of recovery (pull factors) play in recovery progress in 30 people with lived experience. Painful things identified included discovering unresolved trauma, difficult housing transitions, moving away from using friends, navigating a new self/world, hopelessness, family difficulties, relapse and stigma.

Pull factors in early recovery related to making new friends in recovery and gaining tools for recovery – mostly in the settings of mutual aid groups. In sustained recovery those ‘pull factors’ were things like: exceeding expectation of what life might be like, supportive romantic relationships, social networks, stable housing, family reconciliation, finding purpose and making progress in employment.

The researchers found that ‘the pains of recovery rarely led to positive changes’ and that those changes were promoted instead by ‘pull factors’.

Their bottom line:

As recovery is neither a linear pathway nor a journey without residual challenges for many people, there is much to be learned about effective ongoing management strategies in preventing a return to problematic use that utilize a push and pull framework

This confirms my impression that when it come to positive change that carrots are generally better than sticks.

Continue the discussion on Twitter @DocDavidM

References

[1] Gutierrez D, Dorais S, Goshorn JR. Recovery as Life Transformation: Examining the Relationships between Recovery, Hope, and Relapse. Substance Use & Misuse. 2020;55(12):1949-1957.

[2] Hayley Treloar Padovano, Svetlana Levak, Nehal P. Vadhan, Alexis Kuerbis, Jon Morgenstern, The Role of Daily Goal Setting Among Individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder, Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports, 2022,

[3] David Patton, David Best & Lorna Brown (2022) Overcoming the pains of recovery: the management of negative recovery capital during addiction recovery pathways, Addiction Research & Theory,

I’ve often felt very confused about the direction of US drug policy debates have taken over the last decade.

I’ve worked in addictions and recovery since 1994 and have consistently sought to change social responses to alcohol and drug problems from punitive and stigmatizing to therapeutic and recovery-oriented. This happened to put me in alignment with the new recovery advocacy movement that emerged at the beginning of the millennium.

My views have not been static and have evolved as lessons have been learned and contexts have changed. However, in recent years this has placed me in a position where I feel placed in a conservative or traditionalist box. Those labels put it kindly, retrograde is probably pretty accurate.

The experience has been disorienting and confusing. My views had always been considered progressive on drug policy and those views are now categorized as regressive by significant and influential academic and advocacy segments of the field.

It’s become clearer in recent years that the change isn’t that the field has gotten more (left) progressive, the change is that the field has gotten increasingly libertarian.

Keith Humphreys describes how libertarianism, rather than liberalism, has shaped the conditions generating a lot of the recent concern in San Francisco.

What bedevils the city instead is its libertarian, individualistic culture. Since at least the 19th century, Americans have come to San Francisco to be free of traditional constraints back East, to reinvent themselves, to escape the small-mindedness of small towns and to find themselves. This culture underlies the city’s entrepreneurialism, artistic energy and tolerance for diversity in all forms.

But this has a downside when it comes to addiction, which thrives in such a cultural milieu. San Francisco has long been one of the booziest cities in the country as measured by metrics such as bars per capita or percentage of income spent on alcohol. The psychedelic drug revolution and much of the cannabis culture were born in the Bay Area. The “new” crisis around fentanyl is thus not as novel as portrayed: Heavy use of substances has always been part of how San Francisco defines freedom and the good life.

No, soft-on-crime liberalism isn’t fueling San Francisco’s drug crisis. Libertarianism is by Keith Humphreys

When we hear frustration with the status quo, that frustration is often directed at conservatism, traditionalism, moral panic, and entrenched commitment to the war on drugs. This framing, along with advocacy that emphasizes morality and compassion, obscures the libertarian foundations of this criticism and advocacy.

Is it possible that a major barrier to progress on alcohol and drug problems is entrenched libertarianism? Is it possible that this libertarian influence in drug policy discussion limits the imagination and the range of options deemed acceptable?

Humphreys offers three possible futures for San Francisco and links the status quo to the politics of COVID and gun policy.

Just as voters in some regions of the country decide that more COVID deaths are better than vaccine and mask mandates or that mass shootings are preferable to gun control, San Franciscans might decide that overdose deaths and open drug dealing are a reasonable cost to pay for their vision of freedom.

No, soft-on-crime liberalism isn’t fueling San Francisco’s drug crisis. Libertarianism is by Keith Humphreys

While Vancouver and San Francisco get framed as exemplars of progressive drug policy, their policies may owe more to Milton Friedman than to progressive politics or ideology.

I suspect these libertarian and individualistic influences are more pervasive than might appear, showing up in ways that are large and small, subtle and obvious. Off the top of my head, here are a few examples:

Addiction isn’t a spectator sport, eventually the whole family gets to play

One of the things that still haunts me, years into recovery, is the memory of the impact of my addictive behaviour on others – particularly those I love but also my colleagues. There was plenty of suffering to go round, the debris spread far and wide. In some ways the cleaning up operation has never quite concluded.

This experience of ‘collateral damage’ is true for most of us who have experienced addiction, yet research is relatively restricted on the phenomenon, despite the fact that the impact on third parties may be as great (or greater) than the impact on the person with the substance use disorder.

It was interesting then to read a study from Germany,[1] published in the journal Addiction, which looked at the impact of addictive disorders on family members and how this affected their health and mood. Previous studies have shown that relatives can have increased problems with mental health, injuries, higher use of healthcare services and loss of productivity and that these negative consequences are improved by abstinence.

This was a big study involving almost 25,000 people living in Germany. The researchers wanted to get a feel for the proportion of family members impacted in the general population and how severe those impacts were. In this representative sample of people 15 and older, they found that almost 10% of individuals had a relative with an ongoing addictive disorder problem in the last year. A further 4.5% reported that they had a relative with a past dependency. They found that alcohol was by far the most common drug causing problems (80%), followed by cannabis (16%) and other illicit drugs (12%).

Family members affected by addictive disorders had higher levels of depression (doubled) and lower levels of self-rated health. Family members also had higher rates of smoking and risky or binge drinking. There was the suggestion of some good news though relating to the impact of recovery from dependence:

Findings suggest a strong association between the recency of the addictive disorders and ill-health and depression and correspond to the results of analyses from the United States based on health insurance data, which suggest that the psychosocial burden on partners of males with an alcohol use disorder decreases after successful treatment.”

Bischof and colleagues, 2022

I fear we do not pay attention enough to this in our research and practice even though Government Policy in Scotland emphasises the needs and role of family when we consider how we deliver treatment. The recently published final report of the Drugs Deaths Task Force recommended the adoption of a whole family approach and that families should have their own specific support for wellbeing and psychological health.

When families are not considered as part of an evaluation of the impact of treatment, we are missing something very important. Recovery may or may not include abstinence, but measures of recovery progress ought to include the positive gains family members and loved ones make as the individual with a substance use disorder recovers. How well do the families of the people in alcohol and drug treatment in Scotland fare?

A few years ago when I was part of a group supporting the production of the Independent Expert Review of Opioid Replacement Therapies in Scotland, I had an opportunity to take evidence from family members of those with substance use disorders members attending a national conference. It was a bruising experience. Families were not happy with the care on offer at the time.

At the end of the session, although I had gathered a wealth of evidence for feedback, I was left feeling responsible for all of the sins of the treatment system. It was not easy to hear the experiences of people who felt they had let down. The message was clear, family members felt excluded from treatment decisions, did not generally support opioid substitution (though they liked buprenorphine more than methadone) and felt stigma stopped them coming forward.

“The needs of the relatives, friends, co-workers and communities affected by the drinking of people in their social networks are seldom voiced, counted or responded to.”

Brian Coon, writing on this blog last year, picked up some themes that are relevant to this. Commenting on a paper that showed improvements in those with alcohol use disorder who cut back on their drinking but continued to drink heavily – arguably a kind of recovery – he references Kelly and Bergman[2] who point out that heavy drinking can continue to impact on families and that their needs have to be taken into account.

Brian highlights the danger of separating research data from experience. If we are too narrow in our exploration we will not see other things that are important. We are not islands, we are connected into rich social networks, including our family members. Our behaviours affect others. A finely focussed microscope is a limited tool when the big picture is what matters.

Classifying someone as being in successful “recovery” due to the fact that they appear to be functioning but while engaging in very heavy drinking, ignores the potential collateral damage to close significant others (eg, children, partners), whose well-being can be severely impacted by the enduring unpredictability of heavy use. – John F Kelly, Brandon G Bergman

Of course, family members’ recovery ought not to be dependent on the recovery of their loved one. In the residential rehab service I work in, we have a family programme running alongside the patient programme. This is aimed at supporting the families of those we treat. While most people in the treatment programme will go on to complete it and most of those who complete it will find sustained recovery, we have the philosophy that the wellbeing of the family members is not contingent on how well their loved one does – that families can improve their emotional and physical health by mutual support and self-care regardless.

Families can also be supported through mutual aid groups like AlAnon and via local and national support groups. I think the therapeutic effect of family members coming together and supporting each other is very powerful – perhaps more so than one to one support.

In Scotland, the national organisation, Scottish Families Affected by Drugs and Alcohol captures this ethos in their impact report. I’ll finish with a quote from it because I can’t say it better than they do.

“Being able to enjoy a relaxed family meal, ignoring your phone for a while, giving yourself permission to go for a walk or meet a friend for a coffee, or joining a class or a group for the first time are all huge steps for family members. Their everyday lives have been wholly shaped and controlled by their loved one’s alcohol or drug use, often over many years.

Working with families to learn new ways to communicate and interact, be confident in setting boundaries, prioritise self-care, and understand more about substance use and recovery really does change lives and save lives.”

Amen to that.

Continue the discussion: @DocDavidM

Picture credit: Oatawa istockphoto, under license

[1] Bischof G, Bischof A, Velleman R, Orford J, Kuhnert R, Allen J, Borgward S, Rumpf HJ. Prevalence and self-rated health and depression of family members affected by addictive disorders: results of a nation-wide cross-sectional study. Addiction. 2022 May 31. doi: 10.1111/add.15960. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35638375.

[2] Kelly JF, Bergman BG. A Bridge Too Far: Individuals With Regular and Increasing Very Heavy Alcohol Consumption Cannot be Considered as Maintaining “Recovery” Due to Toxicity and Intoxication-related Risks. J Addict Med. 2020 Oct 14. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000759. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33060467.

Elderly senior person or grandparent’s hands with red heart in support of nursing family caregiver for national hospice palliative care and family caregivers month concept

Enabling and caregiving both involve a strong desire to love, help and nurture another person. These desires are amplified, often with a sense urgency and desperation, for those with loved ones in active addiction. The reality, however, is that many of the behaviors that seem “helpful” are actually quite the opposite. We can literally love others to death. Here we will differentiate between caregiving and enabling (which we can also refer to as “caretaking” or codependency), offering a more helpful approach to supporting your loved one in active addiction.

Caregiving is the act of giving care to another person who is incapable of giving it to themselves. For example, it is developmentally appropriate to tie a two-year old’s shoes (if they cannot). Enabling or caretaking, on the other hand, is taking away another person’s ability to do something for themselves. When we get into a dynamic of enabling, we rob the other person of any opportunity to learn and experience the growth necessary to function on their own. This creates a mutual dependence that leads to more frustration and resentment for both parties.

When it comes to addiction, enabling adds fuel to the disease’s fire. If you enable your loved one in active addiction, these behaviors prevents them from experiencing the natural consequences of their own behaviors. Examples of enabling in relation to the addiction process include: giving money to an addict; repairing common property the addict broke; lying to the addict’s employer to cover up absenteeism; fulfilling the addict’s commitments to others; screening phone calls and making excuses for the addict; speaking for the addict or bailing him or her out of jail. It isn’t that these behaviors are “bad” or “wrong”, but it is clear they aren’t working to keep your loved one safe and sober.

To stop enabling isn’t easy. For many, the fear of a loved one losing his or her job, going to jail or overdosing is too much to create any lasting behavioral change. You may have to weigh consequences of short-term pain versus long-term misery in each case. However, the most important thing to know is that you do not have to make any of these decisions alone. Like Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, Al-Anon and Nar-Anon provide space for those affected by the disease of addiction. Sponsors and other members of the community can help you navigate these challenging decisions, set boundaries that you are comfortable with and learn to enable your loved ones’ recovery instead of their addiction.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, “like” the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

For 50 years, Fellowship Hall has been saving lives. We are a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The post Enabling VS. Caregiving appeared first on Fellowship Hall.