We are pleased to announce the release of our newest Tips & Tools for Recovery that Works! video Role Playing.

Role playing is a great way to prepare and practice overcoming urges in circumstances that maybe problematic (dates, weddings, etc.). This tool can help one envision future urge scenarios in their mind, and then play them out with a friend, in advance, to rehearse the urge situation and create the most desirable non-relapse outcome.

Click here to watch this video on our YouTube channel.

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

The mention of Philip Seymour Hoffman in Jason Schwartz’s blog post yesterday provoked a memory. Thomas McLellan, a prominent US addiction researcher and policy advisor, lost his son to an overdose in 2008. He wrote a piece in the Huffington Post a few years ago which has stuck with me. A journalist who had interviewed him referred to the late actor Philip Seymour Hoffman as ‘a weak piece of shit’.

Says McLellan:

“Even as I sit here several days later, I am dumbstruck by the callousness, the audacity, and most of all, the ignorance of this comment.”

He goes on to say:

“Overdosing on heroin doesn’t make you a scumbag. Having a drink after 20 years of sobriety doesn’t make you weak. Having an addiction is not a moral choice. In fact, I think it is accurate to say that having an addiction is not a choice at all.”

Thomas McLellan

He points to the research evidence around the disease of addiction and the effects on the parts of the brain governing judgement, inhibition, motivation and learning and points out that nobody has their first drink with the intention of going on to be an addict. He says:

“I wonder how the media or the public would have reacted if Mr. Hoffman had passed away as a result of another disease that he had been struggling against for 23 years? Say cancer? I think the young actor’s triumph over cancer likely would have been celebrated throughout his career as an example of his personal strength.”

He concludes:

“The science is… strong in the case of addictions and it is time that media and public perceptions about addiction catch up with the science about this disease. Until that happens, too many talented and extraordinary people will struggle in silence and die in the shadows of shame.”

(This is a version of a previously published post)

This post was originally published in 2014.

There’s a lot of commentary out there on Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death. Some of it’s good, some is bad and there’s a lot in between. Much of it has focused overdose prevention and some of it has focused on a need for evidence-based treatments.

Anna David puts her finger on something very important. [emphasis mine]

Let’s explain that this isn’t a problem that goes away once you get shipped off to rehab or even get a sponsor—that this is a lifelong affliction for many of us. There seems to be this misconception that people are hope-to-die addicts and then get hit by some sort of magical sunlight of the spirit and are transported into another existence where the problem goes away.

[NOTE – I know almost nothing of Hoffman or the treatment he received from his doctors or anyone else. My comments should be considered commentary on the issues involved rather than the specifics of Hoffman or the help he received.]

What I haven’t heard discussed much is his reported relapse a year or so ago. How could that have been prevented?

From what I understand, this is someone who had been in remission for 23 years. And, it sounds like his relapse began in a physician’s office when he was prescribed an opiate for pain.

- What’s the evidence-base around treating pain in someone who has been abstinent for 23 years?

- What are the evidence-based practices around how professional helpers should monitor and support the recovery of a patient who has been sober for decades?

- What are the behaviors associated with recovery maintenance over decades through pain and difficult life experiences?

Could the outcome have been different if some sort of recovery checkup had been performed by his primary care physician or the doctor who treated his pain?

Could the outcome have been different if some sort of recovery checkup had been performed by his primary care physician or the doctor who treated his pain?

If he had been in remission from some other life-threatening chronic disease, wouldn’t his doctors have watched for a symptoms of a recurrence? Or, given serious consideration to contraindications for the use of particular medications with a history of that chronic disease?

What if he had been asked questions like:

- How’s your recovery going?

- Have you had any relapses? Cravings?

- How did you initiate your recovery?

- How have you maintained your recovery?

- Have there been changes in the habits associated with your recovery maintenance? (Meetings, readings, sponsor, social network, etc.)

- How’s your mood been?

- What do your family and friends who support your recovery say about this?

Also, if it’s determined that a high risk treatment (like prescribing opiates to someone with a history of opiate addiction) is needed, what kind of relapse prevention plan was put into place? What kind of monitoring and support?

There are two issues here. One is the lack of research, training and support that physicians get around treating addiction and supporting recovery.

The second issue is the role of the patient.

I listened to a talk by Dr. Kevin McCauley this morning in which he addressed objections to the disease model. One of the objections was that the disease model lets addicts off the hook. His response was that, given the cultural context, there were grounds for this concern. BUT, the contextual problem was with the treatment of diseases rather than classifying addiction as a disease. He pointed out that our medical model positions the patient as a passive recipient of medical intervention. As long as the role of the patient is to be passive, this concern has merit. He suggests we need to expect and facilitate patients playing an active role in their recovery and wellness.

So…this was someone who had been in remission for decades. He clearly had a responsibility to maintain his recovery. At the same time, the medical and/or treatment system has a responsibility to monitor and support his recovery.

I happen to have celebrated 23 years of recovery several months ago. I’m still actively engaged in behaviors to maintain my recovery. (Much like I’m actively engaged in behaviors to keep my cholesterol low.)

In 23 years, has a doctor or nurse EVER asked me how my recovery is going? No. Have they ever evaluated my recovery in ANY way? No.

Do they want to check my cholesterol every so often? Like clockwork.

This is a critical failure of the system and the evidence-base. And, we don’t just fail people with decades of recovery. Even more so, we fail people with 90 days, 6 months, a year, 5 years, etc. Then we blame the approach that helped them stabilize and initiate their recovery when the real problem was that we never helped them maintain their recovery. (Then, too often, our solution is to insist that they get into that passive patient role, just take their meds and let the experts do their work.)

via Another Senseless Overdose.

- Who are you?

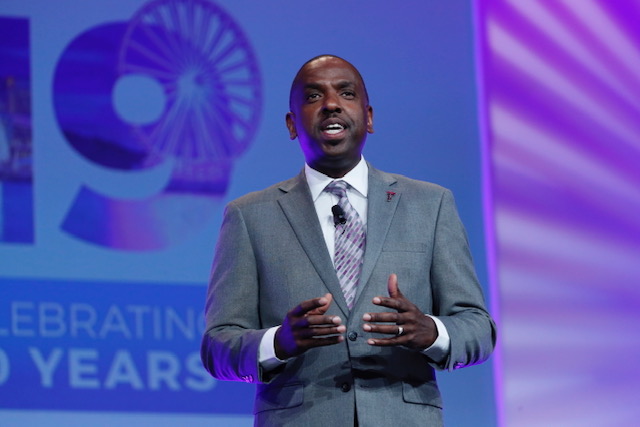

I’m Terrence Walton. I am a husband that just celebrated his 20th anniversary, a father of two small children, and a man who has dedicated his life to two big things. One is the well-being, in every sense of the word, of my family, and then secondly is to help free men and women from addiction – and that includes especially helping people who are helping people get free.

RISE19 Opening Ceremony on Sunday, July 14, 2019 in Oxon Hill, Md. (Paul Morigi/AP Images for National Association of Drug Court Professionals)

RISE19 Opening Ceremony on Sunday, July 14, 2019 in Oxon Hill, Md. (Paul Morigi/AP Images for National Association of Drug Court Professionals)

- What do you do professionally?

I’m a treatment and recovery management professional by training. That’s all I’ve ever done in my entire life as an adult. Right now, I am the Chief Operating Officer with the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP). I hope folks know what drug courts are. We call them treatment courts or recovery courts these days. They are actual courts either on criminal calendars or family calendars for men, women, and youth who are involved in the justice system – not because they are hardened criminals but because they are living with addiction or mental illness that is leading to arrests and/or criminal activity. Treatment courts are designed to help individuals get linked up with effective treatment and effective recovery management, instead of incarceration or just probation without the services they need to get and stay on the right track.

- Do you have any personal interest in addiction and recovery that you’d like to share?

Yeah, I do. I’ve done this for a very long time, and I took a couple of years in the middle of my college career to really decide where I wanted to settle, and I settled here. I’ve often wondered what my personal tie-in to this really is. One is that it’s my calling. This is what I am here, here on Earth, to do. And where that calling came from – the personal basis of it – I think some of it is because I have a long history of addiction in my family, both sides of the family. I have a favorite uncle, my mother’s only brother, who struggled with alcoholism his entire life. I have very early memories of him being sort of lost in alcoholism. I remember one time the family was in the car driving around at night. My two brothers and I were very small and in the back seat. My parents were out looking for her brother and they found him. I didn’t know what was going on, Brian, but I remember seeing him. He was sweating, he was talking out of his head, and my father got out of the car and took him into a place and got him a drink – a beer. And I saw him get better. He was himself. I don’t remember if my parents explained to me what that was about, but I never forgot it. And I think that planted a seed. Also, while I’m not a person who is living with a substance use disorder, I’m an ally of men and women in recovery. And I walk my own recovery journey for my issues that I discovered while working professionally in the field. So, in addition to my alliance with men and women in addiction and in substance use disorder recovery, I discovered my own issue and work a daily recovery practice, a daily personal practice.

- Tell us about your professional experience in the area of addiction and recovery.

I’ve been doing this for as long as I’ve been doing anything professionally. For me that’s over 30 years. I worked for about 5 or 6 years, maybe a little more, doing direct services initially as a tech in a residential adolescent treatment center. And that’s a fancy word for “I observed urines, checked patients’ belongings at intake for contraband, and spent time with young people to keep them from getting into it.” It was there I discovered I really connected with the kids and the work I was doing. I was good at it. I didn’t have much training at that point – maybe two years of college – but I discovered that this is what I want to do. I want to run a place like this. After my direct service time, I soon had the opportunity to take over as director of an adolescent treatment program – earlier than I probably should have, based on how little experience I had. But things went well there. So, I spent the early part of my career directing community-based addiction treatment programs. And about 17 years ago, I became director of treatment for the pre-trial services agency for the District of Columbia. That’s a large pretrial services agency here in Washington, DC. It’s actually a Federal agency. And they had and have a drug treatment court. That’s how I became involved in the drug court world, and very soon I got connected with the organization where I am now – NADCP – as a senior consultant advising them on treatment and recovery matters, and training for them all over the country. I was eventually persuaded to leave my federal position to come on board here in this role. So I’ve had the pleasure of working with hundreds and hundreds of mostly young people and also their families, living with addiction, and probably thousands of professionals who are helping people receive and succeed in treatment and enter long-term recovery. So, I’m enjoying my career – it is what I’m here to do.

- What are you most proud of?

Well first of all, and this is for real, my wife and I started our family late, so we have two small kids— my son just turned four and my daughter just turned seven. I’m convinced that my children are very aware of how much they are loved and how much they and how amazing they are, and that matters to us. My wife and I both believe that this is critical to wellness. And it’s never too late to have a happy childhood, so people can always catch up later. But there’s damage done when children aren’t safe and secure and loved unconditionally. I know that my children feel that and I’m very proud of that. Professionally, when I think “proud”, it’s really gratitude. I’m very grateful that God has given me the ability to do the thing that matters to me and do it really well. And I’m grateful and proud of the influence I’ve been able to have broadly, but especially in the justice system as it relates to working with men and women who are in the middle of addiction and desperately in need of recovery whether they know it or not.

- What keeps you working in addiction and recovery?

You know, I can’t imagine doing anything different. There are certainly opportunities that have arisen for me to do something other than work in the addiction and recovery field. I’ve always easily said “No” to those. Because it is very clear to me –there is no more important and critical work. I am so aware that there are men, women, and young people who are trapped in addiction – they are in bondage – and so much of their potential, what they could do for themselves, their families, our communities, this world, is hampered by the fact that they are trapped and can’t keep the promises they have made to themselves, let alone anyone else. And that bothers me. This world and especially this country we’re living in, Brian, is a mess. And there are people in recovery who will be a part of how we get better as a country. I am convinced of that because real recovery requires self-reflection, acceptance of those who are different, humility, and service. And that’s what this country is going to need to really recover, not just from this pandemic, but from the unrest over injustice and racism, and the resentment of people in certain communities feeling left behind and forgotten. We need people in recovery who possess the values required for us to do well, for this country to heal. So I keep doing this because I know that I’m making investments in our future, and making investments in people being able to at least get on the same journey that we’re all on – trying to live our purpose, find meaning, and make this a better world.

- How has the pandemic affected your work?

There’s no question I didn’t see this pandemic coming. No one did. I had never really given this possibility much thought. I suppose I wasn’t a good student of history – of the previous pandemics. I help lead this organization and we spend lots of time out, throughout the country and the world working directly with teams, court, states, and nations who are implementing treatment courts. Even though I am Chief Operating Officer and my job is based here in the Washington DC area, I spend probably a third of my time on the road: trainings, speaking, and working hand-in-hand with organizations and systems who are trying to help people enter in recovery in a lasting way. Other than webinars from time-to-time, we’ve been accustomed to doing business in-person. We have a significant on-line presence at allrise.org and at ndci.org. However, the bulk of our work is face-to-face and I really value that. I’m a face-to-face kind of guy. We’re that kind of operation. We had to adjust. We had to figure out and accept “This is what is. And this is going to be our new world for a while.” Our mission doesn’t change. My calling doesn’t change. People don’t stop needing help. Programs don’t stop struggling. And so we had to adjust. We closed our physical office for nearly all staff in mid-March. Our office is closed now and we’ll remain closed throughout 2020 at least. I still come in most days, as does one other person but everyone’s working hard from where they are. As the COO, I had to operationally reorganize to be sure the job could get done, and that our team had the resources they need. Only a third of us teleworked beforehand, and that went up to nearly 100 percent. I had to personally focus very heavily on my operational duties, to be sure that progress on our critical mission could continue. Personally, I just had to get used to training and assisting virtually. And fortunately, I remembered that I’m pretty comfortable on camera and found ways to connect that way too. I’m looking forward to a world where we can return to some in-person work. But even as it is, I don’t think we’re missing much.

- What effects of the pandemic are you observing in the people you serve?

I’m seeing significant impacts. And some of the impacts I don’t think we even know yet; we’ll know when we look back and analyze what’s happened to people. This situation has given me the opportunity to have more one-on-one conversations with treatment providers, and teams, regarding their struggles. Many of the people they serve, the clients they serve, the families they serve, are struggling. They had been doing well in treatment court because they have the structure of the court and all that provides, especially the accountability and the reinforcement they get from a judge saying, “Great job! Keep it up!” They’ve sometimes been able to benefit from the best treatment they’ve ever gotten. More than what they might have gotten if they just walked in off the street from somewhere. Perhaps they were finally able to integrate into the larger recovery community. And then, suddenly much of that dropped off. Some treatment courts had to suspend operations altogether for a little bit just to re-group, to figure out how they do court virtually, consistent with laws and regulations. Many treatment providers hadn’t previously delivered telehealth and so they had to figure out how to do that. Part of what sustains many who are early in their quest for abstinence and recovery is drug testing. Many programs understandably had to suspend that. So the suspension of these kinds of things or the lessening of them I think had some big impacts. I talked with a program a couple of weeks ago who has not yet resumed services. That’s unusual – most have. But they haven’t. I fear once that program is able to resume, those participants who they can find are going to needs lots of work to help them get back on track. Another program, during their very brief shut-down, lost three individuals. I mean three individuals died. With one, they are not certain if it was drug-related or not; they know the other two were. Those kinds of impacts are real for the people they serve. Finding ways to adjust and navigate this has been a real challenge. My organization’s job is to figure out how to help them. And we didn’t know, so we had to figure that out for ourselves first. They need resources. We provided a number of webinars and publications. We added a full page to our website, just about getting through the pandemic. Because as I mentioned earlier, pandemic or not, addiction continues. One more thing is this – I remember driving through some of the areas in DC where people who are struggling with addiction get their drugs. And I observed that the drug trade was alive and well. So that didn’t go away, and people still needed help. Yes, there have been significant challenges.

- What, if any, long term effects do you anticipate on the field?

There are probably some good things that have come out of this, but let me first talk about some of the other kinds of effects. I am concerned there may be individuals who are just lost to us – I mean long-term. There are people who were doing well in treatment court and they’re just lost to us. I hope they find a path somewhere else, but for some that’s not going to happen. For some already that’s been clearly the case. I also recognize that the money that the state and Federal governments have had to spend to keep people surviving, and the economy, are going to have to be repaid. I suspect when things settle down, and it’s time to pay the bills, that this may result in cuts in areas that are critical for people’s lives, including funding for treatment and recovery management. I’m already thinking about how we advocate collectively to keep as many resources in treatment and recovery as possible. We also need to be prepared to seek more private sources to help pay for what I fear may be a reduction in public funding for this really important stuff.

- Have you seen any benefits or new opportunities in the pandemic?

I have. I’ve mentioned the fact that I’ve gotten better at this. Well, a lot of people have. There are a lot of courts that have, and treatment centers that have. Many treatment centers that have never done telehealth are doing it now. As a result of that, they are finding ways to reach people that they couldn’t reach before. Even in regular times, it has been challenging for some of our treatment court programs and recovery centers to connect with the people who need them because they are so spread out. Just getting to court, and having to get to treatment, and they have a job somewhere hopefully – it’s been really a struggle. Many drug treatment programs are seeing now that they can continue some of this so that a person who has a job can attend the virtual court hearing on their break and then get back to work. They don’t have to find a way to travel across the town or the state to get to services. I believe that by necessity the justice system, supervision offices, treatment centers, recovery peer support groups, have all been forced to go virtual and make that lasting. Peer support groups like Smart Recovery have always been largely online and so they were in much better shape. AA and NA, where most people get their peer support from, had some virtual meetings and phone meetings, but many of those fellowships have stepped it up so people can see each other. I believe these additions are lasting. They are enormously helpful for access and for people who really want and need to wrap around themselves a support network that is available almost any time. I believe that’s going to happen and is a really positive outcome of everything we’re going through right now.

- If you were able to work on a fantasy project to improve treatment and recovery support, what would it be?

Brian, here’s what I want to see happen one day and perhaps be a part of: I want to focus on two impoverished communities – one in a large urban center, and one in a rural area. Using a cross-systems approach, I want to focus on the people who live there, who have hopes and dreams like everyone else and where addiction is alive and well (because addiction is everywhere), and help to create recovery-supportive communities in an intentional way. Leveraging and building resources in those communities. Part of that effort to create a recovery-oriented community would mean ensuring that people’s basic survival needs are met (needs for shelter, sustenance, safety, and sustainable healthcare). That’s a part of a recovery-oriented community. Because if people’s basic survival needs are not met, it’s very difficult to focus on sobriety and other elements of wellness. Understandably! And as we work on that, we develop or build upon those kinds of services and programs and connections that can help people move from addiction, to remission, to recovery. That means embedding in those communities really good evidence-based treatment and various treatment interventions, including medications to help support recovery. It means recovery centers, and recovery barber shops and salons, and gyms focused and designed for people in recovery – recovery high schools. That’s what I want to see. Let’s start small and be deliberate and intentional in growing it. That’s what I would like to see happen one day soon.

This interview was conducted on 10/07/2020

I was recently on a panel about the future of the field for an APNC event and thought a couple of questions and the notes I prepared might be worth sharing in a post.

What and how has the COVID-19 pandemic shown us about the importance of a multi-year perspective with individuals and inclusion of recovery management services, rather than medicalized care merely focused on initial disease management and symptom suppression?

A couple of things come to mind as a preface to my thoughts about this.

First, a quote from Robert DuPont, “The most striking thing about substance abuse treatment is the mismatch between the duration of treatment and the duration of the illness.”

Second, the conceptualization of addiction as a chronic disease with bio-psycho-social-spiritual dimensions. A recovery plan should address each of these dimensions if we expect it to be successful.

Biological medical models tend to emphasize the role of the medical provider, often at the expense of the agency of the patient. Often, the role of the patient is passive — a good patient is one that lets the doctor and their medications or procedures heal them.

The pandemic has been a psycho-social-spiritual crisis for many of us. And, with all we’ve learned about the effects of chronic stress, we know that biology can’t be isolated from psychology, spirituality, and the social context.

Successful management of chronic diseases typically requires behavior changes that are sustained over time to manage symptoms and prevent relapse. This is much more complex than it might first seem

- These behavioral strategies often include things like changes in eating habits, physical activity, sleep habits, and stress management.

- In many cases, these behavioral strategies involve changing habits that are practiced daily, often multiple times a day, for years and decades.

- These habits are often deeply enmeshed in the patient’s psychology, spirituality, and social context.

- The behavioral strategies involve extinguishing some habits and establishing others

What do we know about maintaining these changes over the lifespan, for years and decades? Unfortunately, very little.

It would be very helpful to know how the trajectory of chronic disease management is affected by important events over the lifespan. For example, how do life events like dating, marriage, divorce, geographic moves, new jobs/careers, job terminations, having children, loss of family members, natural disasters, health crises, retirement, etc affect the course of the patient’s illness/recovery?

Several years back, I looked for research on weight loss and diabetes management over the lifespan and found very little that was helpful.

All of this is to say that understanding the impact of the pandemic on people with SUDs will require:

- a lot of attention to matters that are typically considered outside of the scope of medicine; and

- for us to be present in the lives of people engaged in management of their recovery. We can’t know if we’re not there.

Finally, I’d add that, while we know too little about the long-term multi-dimensional dynamics of recovery management, there are important ways in which addiction treatment has been ahead of the curve. Many of the interventions we’ve been doing for decades aligns well with emerging concepts like social determinants of health.

Many of these interventions extend the duration of recovery support and monitoring, but we need to go further.

What do you see as the next phase of the New Recovery Advocacy Movement? Has the shift to a medical model of addiction helped or hindered this movement’s growth?

- Next phase? I don’t know.

- As the opioid crisis emerged and accelerated year after year, advocacy focused on access to medication, agonists in particular.

- This brought in a lot of medical and harm reduction advocates, and shifted the focus, goals, and values of recovery advocacy.

- The medical advocates often focused narrowly on medication and challenged its framing as a tool to assist treatment and recovery, often framing it simply as treatment and/or recovery.

- Harm reductionists brought in not just a toolkit of interventions like needle exchange and naloxone distribution, but also a philosophy of practice.

- This philosophy often adopts a neutral stance toward drug use, including addictive drug use.

- This neutral stance toward drug use in the context of addiction is complicated for people in recovery.

- Preventing harm, particularly death and chronic disease are unambiguously good.

- And, people in recovery view their addictive drug use as a symptom of a life-threatening illness with severe bio-psycho-social-spiritual consequences.

- A neutral stance toward AOD use by people with addiction is generally incompatible with their experience.

- The scope of advocacy has expanded from advocacy on behalf of people in recovery, to people in active addiction who we want to see get into recovery, and then to people who use drugs.

- All of these advocacy activities often get lumped together into “recovery advocacy.”

- There’s a Venn diagram in there, with significant overlap, but advocacy for people who use drugs and people in recovery are also going to diverge in important areas.

- Both are important, but they are not the same thing.

- I think sorting this out is an important task in the coming years.

- There’s a lot to overcome. For example:

- Most people in recovery from addiction will describe it as an experience of loss of control or impaired control–a loss of agency to the illness, the addicted self. Many advocates focused on people who use drugs reject the notion of a true-self and an addicted-self.

- People in recovery see recovery and change at the individual level as a critical outcomes while other advocates see focusing on individual behavior as blaming the victims for social/cultural failures.

- The lowest hanging fruit might be developing better ways to differentiate addiction from other drug use, and tailor approaches to the type of use. (Maybe recovery-oriented harm reduction?)

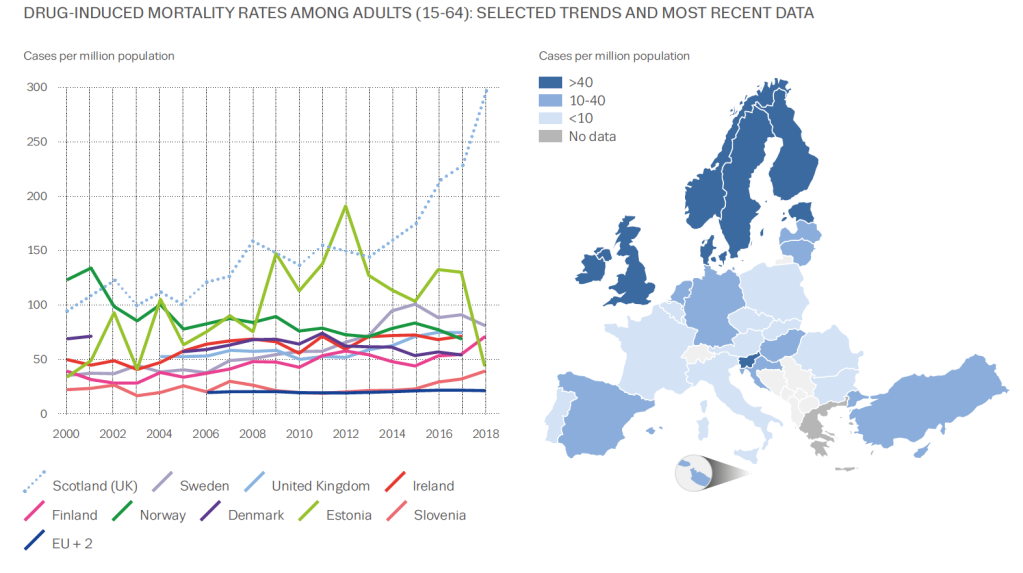

Graphic from European Drug Report 2020: Trends and Developments

Graphic from European Drug Report 2020: Trends and Developments

It’s not often graphs elicit an emotional response, but this one did for me. It’s from the EMCDDA’s recent report on drugs in Europe. The map shows that the UK has high levels of drug-induced mortality compared to most of Europe. But look at the dotted blue line on the graph. That’s Scotland. Worst in Europe and possibly the world.

It’s not a new phenomenon, our high drug-related deaths. The Scottish Drugs Forum makes the point: ‘Drug overdose deaths are preventable. We know how to prevent these deaths and yet they still happen.’

Kindness Compassion and Hope

So what’s being done about it? One of the highest-hit cities is Dundee. A commission set up to look at drug-related deaths took evidence from over 1000 people and made recommendations which included changing the system and culture, having holistic and integrated care and addressing the root causes of drug problems. The report title was Kindness, Compassion and Hope, which feels inspiring.

The Scottish Government has invested in treatment services with a particular emphasis on reaching more at-risk people and retaining them in treatment. Last summer it set up the Drugs Death Task Force, a group chaired by Dr Catriona Mathieson which has highlighted the need for wide distribution of naloxone, an immediate response pathway on non-fatal overdoses, medication assisted treatment (MAT), the targeting of those most at risk, public health surveillance and provision of equity of support for those in the criminal justice system. The Scottish Government has put £1M into research and £4M towards the task force’s six recommendations.

Standards for MAT have been developed, the country has a three week target from referral to treatment, ready access to prescribing, treatment free at the point of delivery, routine overdose prevention training, widespread naloxone distribution, generally accessible injecting equipment provision, low threshold clinics in many places and a high public awareness of the problem. In addition, there is investment in research which looks to find solutions to the problem. But is it enough? – the causes of our drug deaths are complex and rooted in poverty, exclusion, trauma and hopelessness.

A public health emergency

“What we are facing in Scotland is a public health emergency,” Joe Fitzpatrick, Scotland’s Public Health minister stated recently. “I am prepared to consider any course of action that is evidence based to save lives, whether its controversial or unpopular.”

Too controversial for the UK government are drug consumption rooms which Glasgow in particular wants to trial. Drugs policy is not devolved to the Scottish Government and Westminster won’t consider changing the law to allow this to happen, though one crusader is flouting the rules to deliver this currently.

One area in Scotland where consensus is growing is around the likely benefits of shifting to a public health approach. A cross-party parliamentary group, The Scottish Affairs Committee, held an enquiry into the subject and reported at the end of last year. It asked the UK government to declare a public health emergency making the point that the criminal justice approach has failed. It highlighted how current legislation on drugs stands in the way of tackling the issue from a public health slant.

And the UK government’s response? Pete Wishart, the group’s chair described this as ‘the almost wholesale rejection of recommendations.’ The Guardian has suggested this rejection of what multiple experts think is best for Scotland can only fuel calls for independence. When you consider that the UK government hosted a summit in Glasgow last February without consulting the Scottish Government or asking people with lived experience to attend, you begin to grasp the depth of the gulf that separates the two approaches.

The role of visible recovery

I wonder in all of this what the role is for recovering people, recovery communities and the powerful protective effects of developing strong social networks for those most at risk. What if we studied whether developing new social networks had a significant effect on Scottish drug deaths? What if we developed drug consumption rooms which were strongly recovery-orientated with visible recovery present? I suspect, that at the very least, this would boost hope. Hope is often in short supply in addiction, and anything that augments it is welcome.

Perhaps if every outreach service, every injecting equipment outlet and every treatment setting had people with lived experience prioritising the connection of those at most risk not just into treatment but also into a variety of supportive recovery-oriented settings, there could be a positive impact on drug deaths. Perhaps this would help people begin a cultural journey, moving from the culture of addiction to a culture of recovery as Bill White sets out. Not the only thing to be done certainly, our approaches need to be multiple, but something that doesn’t require the permission of the UK Government and which may augment the other interventions.

The Drug Deaths statistics for Scotland for 2019 have been delayed due to COVID, but will be published soon. I’d like to see that dotted blue line on the graph reducing, but that is by no means certain and much remains to be done.

The True, The Good, and the Beautiful

In his lecture titled, “The True, The Good, and The Beautiful” Roger Scruton asks what these three things embrace and what they have to do with each other. Overall, the subject matter of that lecture is aesthetics: the philosophy of art and beauty.

Scruton states that pleasure says, “Come again” and knowledge says “Thanks”. And therein lies a problem. How so? He elaborates that some experiences that are pleasurable are harmful, and that putting aesthetic values first in a hierarchy of values is a kind of “immoralizing”.

He asks what we learn from art, and if what we learn from art is a kind of truth not available from any other human activity.

He states by extension, in life, one may live a moralizing existence or find moral qualities within the experience of living. Is it even possible to not?

Ugly Truths?

In his blog post concerning children living with an addicted parent during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, William White wrestles with the topic of that truth, the bad side of that experience, and its ugliness.

(Incidentally, for many years one of my fantasy projects for our field has been that researchers would meet with large numbers of those with the lived experience of being raised with and by an addicted parent, and meet with other family members – to obtain information about what addiction illness consists of, and what recovery could hopefully look like. After all, only asking the one with the addiction illness is an information retrieval endeavor problematized by various features of the illness.)

Further, some involved in thinking about addiction, addiction treatment, and addiction recovery, have touched on or struggled with the possible inclusion or exclusion of a moral dimension in their considerations.

Anesthetic and Feeling

Interestingly, Scruton notes the word “anesthetic” contains the root word for “feeling”. That is interesting to me because many substances diminish naturally occurring feelings and diminish subjective experiences. And this causes me to wonder if either the philosophy of aesthetics or study of anesthetic functions can serve as a window into the moral dimension of addiction disease and its progression. As an example of that line of inquiry, I have spent a number of years studying the research literature concerning the simple harms that result from simple use.

Within that study, the information I have found most fascinating describes acetaminophen reducing both pain and pleasure, with unexpected effects:

- Diminishing the pain of decision making, reducing the positive value of feeling pain while weighing possible options (DeWall, C. N., Chester, D. S., et al 2015)

- Diminishing social pain, such as pain felt when socially excluded (DeWall, C. N., MacDonald, G.M., et al 2010)

- Reduced meaning threats, such as discomfort in considering existential meaning (Randles,,D., Heine, S. J., et al 2013)

- Diminished psychic pleasure and pain (Durso, G. R. O., Luttrell, A., et al 2015).

Acetaminophen dampens neuronal activity and thus both pain and pleasure. And as these researchers show, acetaminophen dampens the neuronal activity underlying pain and pleasure, not just the feeling of pain.

I also find it interesting that naltrexone produces anhedonia to music (Mallik, A, et. al., 2017).

Substance use, then, can be viewed as simply as access to various indigenous forms of anesthesia, like acetaminophen. What can be said of the functional life impacts resulting from the blocking of pleasure and pain by use of alcohol, opioids, cannabinoids, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, and cigarettes? For example, what does life look like aesthetically for the user? And what does life look like aesthetically for the witness? As Scruton states, there is the kind of art that is like sadness in a frame, or the kind of art that produces the kind of sadness that hurts you.

Factual Information vs. The Purpose of Art

In describing the value of the philosophy of art and the study of aesthetics, Scruton differentiates the mere instrumentality of factual information and the kind of thinking and judging that is done for someone on the one hand, from the purpose of art on the other hand. And within art he differentiates art that is blatantly moralizing from moral qualities that might be present within art.

Scruton states one does not go to art for factual information as the primary aim, but one goes to art for the experience. He extends that notion by stating not all truth is at the level of factual information, but that in some experiences of life, or of art, we may find a different kind of truth in the form of trust, support, or genuine spirit. “From the heart, to the heart”, as he says. He goes further and applies this to the emotional dimension. He defines “false emotion” as when the “I” eclipses the “you” – deriving from a certain kind of self-involvement that is harmful to others.

Thus, the aesthetic aim of the artist and aesthetic experience of the one experiencing the art may be similar or differ, but they will connect regardless – for better or worse, pleasurably or painfully, authentically or insincerely. After all, as Scruton explains, arguments about taste differences in aesthetic judgment “concern the matters of the soul”. And art puts us in a position of rendering our own judgment, not just receiving facts or judgments others make for us.

Does Addiction Have A Moral Dimension?

Scruton states that in matters of philosophy the greatest value is often in the clarity of asking a certain question and in carrying certain questions, but that often no further clarity is obtained in answering them. Is the possible inclusion or exclusion of a moral dimension in matters of understanding addiction, addiction treatment, and addiction recovery a question best asked and not answered, or a question that is best answered rather than only asked?

He gives us a hint toward a solution of that puzzle.

Scruton differentiates the kind of “truth” that is merely straightforward and literal, from the kind that is personal, subjective, and rescued from mere functionality or sentimental pretense. I apply that from two perspectives and for me they are not in tension:

- From the standpoint of mere information and sheer facts of a medical-scientific perspective, addiction disease and progression are not a moral matter per se.

- Concerning the aesthetic dimension of lived experience, to tell a child or adult child to eliminate or diminish the moral dimension would perhaps seem immoral or amoral, hurt or seem hollow, or simply seem silly and wrong.

Back to The True, The Good, and the Beautiful

Which leaves us with the topic of addiction recovery. If recovery is true, good, and beautiful, is it not a moral endeavor? Many children and adult children know that it is.

References

DeWall, C. N., Chester, D. S. & White, D. S. (2015). Can Acetaminophen Reduce the Pain of Decision-Making? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 56:117–120.

DeWall, C. N., MacDonald, G. M., Webster, G. D., Masten, C. L., Baumeister, R. F., Powell, C., Combs, D., Schurtz, D. R., Stillman, T. F., Tice, D. M. & Eisenberger, N. I. (2010). Acetaminophen Reduces Social Pain: Behavioral and neural evidence. Psychological Science. 21(7):931-937. DOI: 10.1177/0956797610374741

Durso, G. R. O., Luttrell, A. & Way, B. M. (2015). Over-the-Counter Relief From Pains and Pleasures Alike: Acetaminophen blunts evaluation sensitivity to both negative and positive stimuli. Psychological Science. 26(6):750–758. doi:10.1177/0956797615570366.

Mallik, A., Chanda, M. L. & Levitin, D. J. (2017). Anhedonia to Music and Mu-Opioids: Evidence from the administration of naltrexone. Scientific Reports. 7, 41952; doi: 10.1038/srep41952.

Randles, D., Heine, S. J. & Santos, N. (2013). The Common Pain of Surrealism and Death: Acetaminophen reduces compensatory affirmation following meaning threats. Psychological Science. 24(6) 966 –973.

Suggested Reading

Solomon, R. L. (1980). The Opponent-Process Theory of Acquired Motivation: The Costs of Pleasure and the Benefits of Pain. American Psychologist. 35(8), 691-712. doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.35.8.691

Stigma is commanded by a deep irony: where peer pressure is what likely keeps us quiet, peer support is what enables us to speak up.

Paul E Terry

One of the ways to counter stigma is for people with lived experience of addiction and recovery to share their stories. Indeed, Pat Corrigan, a respected stigma researcher, says that of the three approaches to tackling stigma – protest, education and contact – it is contact between members of stigmatised groups and ‘normal’ people that can increase understanding and dispel myths.

Mutual aid groups offer forums where this can happen. Sadly, there is also evidence of prejudice towards such groups. In Jonathan Avery’s book, The Stigma of Addiction: An Essential Guide, which has plenty to recommend it, there is, ironically, one toe-curling section about mutual aid groups where it seems myths are not dispelled but reinforced.

Avery argues that 12-step mutual aid groups ‘perpetuate the stigma associated with’ addiction. He argues that they do this by having features which ‘run counter to a science-based understanding of the disease of addiction’. These features are:

- Peer-based care

- Complete abstinence

- A paramount goal of anonymity.

He argues against these features saying:

- Best practice for addiction care calls for treatment to be delivered by a qualified health care professional

- 12-step groups generally frown on medication; they hold abstinence up ‘as a primary goal of treatment’

- And he says that anonymity gives the impression that being in a mutual support programme is embarrassing or shameful.

Where to begin?

It’s a challenge to know where to begin with this. Ignoring the fact that, according to Kurtz, AA members had a large role in spreading and popularising the disease concept of addiction, it’s an almost laughable irony that mutual aid groups get stigmatised in a book tackling stigma in addictions. Addiction stigma is bad enough, but recovery stigma? So, what’s the deal?

Firstly, mutual aid is not treatment, nor does it set treatment goals. The clue is in the title, it’s peer to peer aid or support. It is however true that 12-step facilitation (TSF) is a structured intervention used in treatment settings that is designed to encourage uptake of community-based mutual aid groups.

As it happens and while we’re on the theme of irony, getting people to engage with AA via an intervention like 12-step facilitation has been found to be as effective, if not more effective than accepted treatment interventions like motivational enhancement therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy. So, the idea that helping people into recovery should sit entirely in the domain of the expert is not only anachronistic, paternalistic and condescending; it’s wrong. Members of mutual aid groups may not be experts on addiction treatment per se, but they are experts in community recovery.

On medication

Secondly, AA’s stance (on which they sought advice from doctors) on medication is clear – it’s wrong to deprive anyone of medication that can help, although AA rightly highlights risks of cross addiction with some medications. It’s fair to say that, as in any diverse group, individual members will have their own opinions which could differ from AA’s and be harmful, but the organisation does not condone this.

For NA, I think it’s a bit more complex. I see it as an organisation for those seeking abstinent recovery – who don’t want to be dependent on either illicit or prescribed drugs, and there is a legitimate debate to be had about the role of MAT, but nevertheless, NA literature states: “the choice to take prescribed medication is a personal decision between a member, his or her sponsor, physician, and a higher power. It is a decision many members struggle through. It is not an issue for groups to enforce.” Hardly frowning on medication.

On anonymity

Thirdly, while the 12-step emphasis on anonymity grew in part out of the shame and social stigmatisation associated with alcohol dependence at the time AA was set up, this was only part of the story. It was felt that people would not be likely to attend meetings where there was not the safety of remaining anonymous. That was a pragmatic approach back in the middle of the last century and it many will feel its validity stands today.

It’s not only about this though. We expect our doctors to keep our anonymity and confidentiality secure, not because we are ashamed of our health issues, but because it is an important principle that it should be up to us what we say about our medical history.

According to AA literature, the organisation had another reason to promote anonymity. They wanted to keep all members on the same level – they aimed to maintain anonymity in the media, to avoid a cult of personality and have a goal of maintaining a degree of personal humility.

Deep irony

However, this approach does not mean members cannot share about their recovery. As AnneMarie Ward, CEO of FAVOR UK says: “I’m an advocate because I know anonymity doesn’t mean invisibility’. Indeed, many people who do go public are members of mutual aid groups. Around the world, recovery communities are actively tackling stigma by being visible and sharing their stories.

Mutual aid groups and their members are not perfect and there are legitimate debates to be had around legitimate criticisms, but the weight of evidence for good vastly outweighs the sort of accusations Avery levels against them, even if these assertions were robust. However, the accusations are not robust, they reinforce myths about mutual aid groups and risk stigmatising them.

Now to find this in a book about addiction stigma – that’s what I call a deep irony…

Who are you?

That is a loaded question!

My name is Kristal Reyes, and I am a person in long-term recovery.

I am also a wife, I’m a mother, I’m the Director of Crisis Services for Neighborhood Services Organization [NSO] in Detroit. I’m also the Clinical Director for First Step Referral Services, and I’m a lecturer for the University of Michigan-Dearborn.

Tell us a little bit more about what you do professionally.

I work within the realm of severe and persistent mental illness and behavioral health, more specifically substance abuse. With NSO, my work there is to do assessments and to get people into the proper level of care. So, if you are suffering with a severe, persistent mental illness, then I wanna get you into the right level of care for treatment. If you come to me in my private practice and you are suffering with some form of alcohol or drug abuse or dependency. I also wanna get you into the right level of care.

Okay, so I work primarily in Wayne County in Washtenaw County. In Washtenaw, I provide services for folks that suffer with severe and persistent mental illness as well as those folks that have drug addiction or abuse.

In the city of Detroit, I serve the most vulnerable population. I serve the folks who come into the emergency room, most of my patients are actively psychotic, and my job is to send a team in to do a bedside assessment and try to get them in the least restrictive care possible and to get them to the best care that they can get.

You mentioned that you’re a person in long-term recovery, do you have any other personal interest in addiction and recovery that you like to share?

So, you know, it’s so funny you asked me that… I was talking to my 11-year-old son the other day and, ironically, we were talking about death. I told them that I wanted to be cremated, and he asked me, where did I want my ashes sprinkled? I told them I wanted them sprinkled at Dawn Farm, and he thought that that was so odd. I explained to him that prior to August 30th, 2011, I didn’t have a life worth living, and so being a person in long-term recovery for me is the greatest gift that I’ve ever had, it was like my second birth. My recovery day is more important to me than my birthday. It was the day that I had the opportunity to become a mother… I was already a mother, but I was allowed to become a mother to my children. Recovery has allowed me to get married, to have children, and to help other people just like myself.

Tell us a little bit more about your professional experience in the area of addiction and recovery.

So I got my undergrad at Eastern Michigan University, I stayed there and got my graduate degree in social work with a concentration in mental illness and addiction. I started off and Dawn Farm. So you gotta know I went through the Farm in August of 2011, and literally the day that I reached that two year mark, where I could work, I began working at Spera, their detox. [Dawn Farm requires a waiting period of 2 years before hiring alumni.] And I’ll tell you, it was the best ever. I probably worked 40 to 60 hours a week. I worked so much they told me I needed to stop working. I worked there until I completed my master’s program. Dawn Farm has always had a special place in my heart [obviously! ] because I went through there. I still keep in contact with former Farmers, I still keep in contact with the team that works over there, I share clients with them on a regular basis.

Following Dawn Farm, I had a short stint with outpatient services at Hegira. I left there and came over to NSO where I started with the COPE team [Community Outreach for Psychiatric Emergencies]. From there, I went from working as a COPE clinician to the program manager, to the director, and now just recently, I am now director of our substance abuse programs that we are implementing, which is an evidence-based MAT [medication-assisted treatment] program.

Professionally, what are you most proud of?

I’ll have to say the work I do at First Step Referral Services. Lots of our clients come from the court, and having the ability to see someone walk in… and to see them walk out, as this kind of changed person is such a gift. I knew it from a personal level– what recovery can do–but watching some of these folks come in and the light bulb goes on. Being a person in recovery and working at Spera… I’ve seen some of the sickest people that you can see, right? But sometimes those people that are kinda in the middle, before they have to get to go into Spera… So, a first DUI or a minor in possession… I had a client come in the other day, and he tried to bullshit me with his using history. I pulled my mask down and I was like, “Dude! I’m with you. I’ve been there.” And, I told him that smoked weed I drank, and I was a felon. He was like, “What?”

What we had was that ability of one addict relating to another, but it was on a totally different level. You could tell that his guard went down, and he was able to share his experience with me.

I think that one of the biggest pieces of the work I do right now is from a few years back when I got the ACEs training. After that, I was able to put into perspective the adverse childhood experiences and actually find… not necessarily that reason… but being able to help somebody with the why. Why do I keep using? Why am I like this? Why am I an addict?

We’ve been getting a lot of calls from these young folks that are getting tickets for driving under the influence of marijuana and for them to come in here and for us to have an opportunity to share with them… not my position on weed or not my story of my marijuana abuse. But, to share with them like, “Hey, I understand why you smoke weed… this is what it does for you… this is why you smoke it. When you’re ready… when you’re willing to look at some of these things and find some different coping mechanisms, call me because I’m here to help. Then, when the phone rings a week, or two weeks, or a month later, and that same 21-year-old kid is like, “Hey man, maybe I don’t need to smoke weed.”

I think that that has been the most rewarding of all the accolades that I’ve had. It’s just kind of seeing the light bulb go off.

What keeps you working in addiction and recovery?

That’s part of it. But in all honesty, those four little boys that I have. I am the first person in my family that has been able to have children that don’t have to have parents that are using addicts. I can’t take back the trouble and the trauma that I caused my oldest son… being the child of an active addict. I cannot change that, I cannot fix that. But this year marked my ninth year clean, which was the exact timeframe that I was using. So for me, that was a huge gift. I get to be clean the same number of years that I used. So now, those three little boys that I had after him, never have to see me high.

So I get to help those mothers and fathers, those first generation people to have the understanding of recovery. When I got here, I had no idea that people live without drugs. NONE! I’ll never forget this, when I had my intake at treatment, he asked, “So what do you want?” I said, “I just wanna drink and smoke weed like everybody else without getting in trouble.” And he was like, “You know what kid? You belong here.”

I never ever had a goal of never using. I just wanted to feel human. I just wanted to work a regular job and stop getting arrested. I didn’t know that I could have a life worth living that didn’t include any mood or mind altering substances. For that, I’m so grateful, and I just wanna give that to everyone else. I just wanna offer it. I wanna wear recovery on my forehead. Like, “Hey! If you want this thing, you get to have it. It’s free. I’ll tell you all about it. It doesn’t cost anything.”

How has the pandemic affected your work?

So I think a pandemic has probably affected me personally more than professionally. I’ve seen a lot of people that I’ve been really close to that just simply couldn’t handle the pandemic, they couldn’t handle not going the meetings, they couldn’t handle the change that came. I’ve seen a lot of people go out with days, and weeks, and months, and years, and decades clean, and that’s been a really hard thing to handle.

The other piece to that is knowing that there’s no access to treatment. If you work in this field, and you know that when someone calls you when they want treatment, you’ve got about five minutes to get them in and to get them a bed. When the pandemic hit, things just stopped. Meetings stopped. Recovery stopped. Access to treatment stopped. For the first time in my entire professional and personal life, recovery as I knew it was on hold.

So that meant the newcomer didn’t have a safe place to go. No one was brewing coffee, and most importantly, Spera closed its doors. For that was traumatic in itself… where do these addicts go? What are they supposed to do?

So I left my phone on at night. I stay as close to work as possible. We found that a lot more people were calling us… they were just Googling trying to find somewhere to go. We got a lot of cost for methadone and Suboxone, and I don’t provide that here. So I spent a lot of time on the phone with sick and suffering addicts who were looking for help, and I just simply couldn’t provide it. for the first time, I didn’t have a number to give them.

As far as my work with NSO… I think that’s the part that hit us the hardest, because COPE shut down. We were no longer able to go into the hospitals to see our patients. And the other side to that is the folks that were in recovery with severe system mental illness… their lives changed, they were afraid. If you already suffer with schizophrenia or paranoia or anxiety… in the pandemic, that is tri-fold now. These folks were afraid to leave their homes.

I lost a really good co-worker of mine during the pandemic, not to COVID, but to untreated mental illness because he was afraid to leave his house. So he stopped reaching out, he stopped going to work, he stopped taking his medication because he ran out and his paranoia got the best of him. He committed suicide after 20 years in recovery with severe and persistent mental illness.

You’ve already spoken to this, but do you have any more to say about the effects of the pandemic on the people you serve?

I think one of the unintended consequences is the increase in [AOD] use, people are using more.

People that didn’t ordinarily use… or the people that were… I hate to use this term… but I’m gonna use it ’cause I can’t think of anything better… people that were functioning alcoholics… people that drink after work, but could get up and go to work every day, never had a DUI, folks that smoke weed at the end of their shift but got up and went to work every day and didn’t really have any hard consequences of their use… all of a sudden their job was gone. So those folks that would wait until 5:30 or 6 PM to drink, all of a study started drinking at noon. And, as you know, their body can develop dependence to alcohol without permission.

So we started seeing an increase in younger people coming in that were smoking more marijuana than they had before. On top of the fact that they had been working, but now you have an increase in unemployment benefits. They’re already living check-to-check, but now they’re getting on employment benefits, they have no requirements as far as getting up and going to work, so they’re starting to drink earlier in the day and drinking later on in the evening.

The other piece that I think really got a hold of me are the children. I don’t think that people really understand and that a lot of the families that we service have kids at home, and those kids to look for their parents to go to work and keep stable. Those kids look forward to going to school every day. Without school, parents are now more stressed out, they’re home with their children, they’re using, they’re smoking and drinking at home now on a much higher level than they were before. Kids aren’t in schools where they’re staying up later. The unintended consequences of seeing their parents drinking and smoking more often. And now that school’s online, we’re seeing the same thing. You’re seeing parents that are like, “it’s legal to smoke weed.” So, they’re smoking weed and the kids “classrooms.” Before, at least kids would be able to get that eight hours a day away from their traumatic homes, and away from their parents were smoking and drinking at home, to go to this place where they felt safe and secure, and now they don’t have that.

So you have stressed out parents who already have risk factors, that are now increasing their use, and these kids that are stuck at home since March of last year without any outlet at all, without any safe space. It seems like these kids are on this heightened sense of awareness… they’re on a 10… an emotional level of a ten, consistently. From our work in crisis, we know that that’s not good for their brains, it’s not good for their living, it’s not good for their sleeping, and it’s also a predisposition to them using drugs and alcohol at an earlier age. I’m really concerned about the long-term effects of this pandemic on these youth… their life has just been completely disrupted.

What, if any, long-term effects do you anticipate for the field?

Well… in 2018, when I got a promotion at NSO, I sat at a table and I discovered that clinically, I was good at what I did with individuals and small groups, but I started to learn that I needed a different piece to this puzzle in order to be as effective as I really wanted to be.

So I went back to school and I will graduate with a Masters of Public Health in December from Purdue. What that education has taught me is a population view, so I think one of the long-term effects that we’ll see on this is the effect that it’s having on the kids.

I think that that’s going to have a huge impact–the effect that it’s having on the youth… the youth that didn’t have access to high-speed internet at home, the youth that were not able to go to school to kinda get that reprieve, the youth whose ACEs [Adverse Childhood Experiences] scores just jumped from a 4 to 7 over the term of this pandemic. That’s gonna be, I think, the biggest consequence, at least in my field right now.

The other piece to that, I think, is going to be once things loosen up a little bit, because the pandemic is one thing, but there’s a whole other health crisis out here that we’re fighting along with the pandemic, and that’s the systemic racism. Because of this, you’ve got this inequality as far as getting into treatment and having access to beds. I think we’re just gonna see that multiply.

We see that here. I see clients right now that I don’t charge because the Ypsilanti Transit Center has decided to transition some of their routes, and so some of these people who could normally go to another treatment provider under their Medicaid coverage can’t get it. Or, because of COVID, they can’t get there with their children… it’s an hour and a half bus ride or there’s no bus ride at all. So they come to us because we’re right in their neighborhood. So I take them in, and provide treatment, and give them resources to the best of our ability. I think we’re already seeing some of those effects, and those effects are just going to increase.

Do you see any new opportunities in the pandemic?

Absolutely. One of the best things that’s happened in the pandemic is the increase in telehealth. Telehealth was one of the most underutilized interventions known. You had to have really great insurance for it to be covered and even then, it was touch and go.

One of the benefits that I think I had in my private practice was the fact that because we were so small, it was easy to change, like there was no red tape, there was no bureaucracy. It was like, “Hey, we gotta do this. This is what we’re gonna do.” Now, my husband is taking a little longer to transition over. [laughter] He was really skeptical. But for me, it was like, we just need to do this now.

So, there was not really a time that we had a lapse in treatment for folks. But that was for us. For these larger entities, this is a huge undertaking to offer complete telehealth under the HIPAA guidelines. For us, it was just super simple, refer these larger entities, not so much. One of the things that we’ve seen with our outpatient groups is the difficulty in keeping folks connected, so to speak.

So before you’re coming in… if you know anything about addiction, that the number one treatment modality for addiction is connection, right? We know that upfront, whether it’s connection in AA or NA, or connection in treatment, it’s connection. Connection with other addicts in recovery. So, when you take that platform away and you put it all on the screen… I don’t know about you all, but there’s been a myriad of meetings that I’m in that I’m supposed to be paying attention and I’m doing 10 other things. So we find in outpatient that it is a little bit harder to keep people engaged than it was when everything was in person.

So I think that taking that extra step and making those phone calls and connecting with people that way. I run a woman’s group for trauma survivors, and I find that we’ve been text messaging. That was under-utilized on my end. So, being able to meet with them on Zoom and then text messaging them here and there, or allowing them to text message me if necessary, has been super helpful.

For sure, Telehealth. Let me just say this, we talk as social workers a lot about meeting people where they are, but not leaving them there. This pandemic has allowed us to literally do it. I’m literally gonna meet you in your living room, right now! If you want treatment, here I am, I’m gonna meet you in your living room with your scarf on, your doo-rag on, your kids running around the background. If you tell me that you want services and you tell me that you want treatment, I’m gonna give it to you right in your living room you don’t have to leave. I find that when I tell people that… when folks coming here that have been sent by the court, or they just walking in, I can say, “I can meet you where ever you’re at. I can meet you in your living room. Send me your email address, and I’m gonna literally meet you in your living room.” And they say, “I don’t have a laptop.” I say, “Do you have a phone? So here we go.”

So I think that that this was definitely underutilized. I’m so helpful that when the pandemic and the consequences of it begin to kind of lessen and die down, we will still have the opportunity to continue to use this platform. I think that we have the capability of reaching so many more people this way. Not everybody’s ready to walk out into the world, but if you can meet them and their living room… that’s a good start.

Last question, if you were able to devote yourself to a fantasy project to improve treatment and recovery support, what would it be?

I would like to say it’s a tough question, but it’s not… it’s really easy. For me, it would be universal health care. Because, if there was universal healthcare, if there was universal access, then there would be no wrong point of entry. Right now, I have to turn people away because I can’t take everyone for free. Right now, I have to do an assessment with someone and hope that they follow up with the recommendation that I’m giving them.

For people that don’t know, I got to Dawn Farm literally by the grace of God. I didn’t live in Washtenaw County. I hadn’t been to treatment before, they literally gave me a $10,000 bed.

I’d like to think that at this point, I’ve paid that $10,000 back by staying clean and giving back. So I try my best to take in as many clients as I can that don’t have the ability to pay. But, to be someone in recovery and to see that sick and suffering addict, to see that mom that needs help, and that I can’t give them help, when I have the resources, I got a door, I got a table, and I got a degree. But to not be able to service them simply because they can’t pay or because they don’t have the right insurance is really hard for me. So if I had it anyway, it would definitely be universal healthcare, because then it wouldn’t matter. Then, whatever door they came in… if they came in because they needed childcare, I could help them with their substance abuse. If they came in because they had a severe and persistent mental illness or they had depression, I could help them with their substance abuse. This way right now, there is so much red tape, it’s so hard to get treatment to the people that need it and want it the most.

I think the other project to go along with that would be… I’m a firm believer in the ACEs study… that these experiences… this trauma that we have as a society. I’m a firm believer that our alcohol and drug use and addiction are directly correlated to the life that we all have to live. So… I remember someone sharing with me, I wanna say it was William White, about plucking the tree out of the woods. You pluck this dying tree, and you stick it into this recovery area and it gets bold and beautiful, and then you take it out and you put it back in that same environment, it dies.

But what if we put recovery in the community?

So one of the goals that I have… my five-year plan… is a building down here… I don’t know how far that’s gonna go, and I’m gonna tell you a secret. There’s a building out here… down the role from us… near Eastern [Michigan University] that’s been empty for years. Every time Rhett and I drive by it, our goal is to purchase this building so that it can be like the epicenter of recovery… where no one that walks in that door is turned away. If you want services, you come in and we help you figure it out. Almost like the Ozone House [a local youth shelter and support program] is for kids, but this is for anyone that wants treatment… anyone that wants services.

So my ultimate goal is to open that building and have it open and brighten up the Ypsilanti community where I live, work, and play.

So the recovery is possible for anyone that wants it.

Boo! How to Overcome the Fears of Sobriety

October is notorious for ghouls, goblins, and ghosts galore—all things that scare us and can make sleeping at night a daunting task. In terms of “spookiness,” Hollywood-esque images of creepy dolls and terrifying clowns may come to mind. When it comes to your recovery, you may be facing some fears and scary night-time images of your own.

If you’re new to recovery, this huge overhaul and journey that you’re embarking on is probably quite scary! Even if you have time in recovery, the day to day struggles can be equally as terrifying. The fear of returning to use, being the most obvious, can be all-consuming at times, but there are countless other anxieties associated specifically with early recovery.

Who will I hang out with? Where will I find new friends? Will people still like me when I am sober? How will I cope with stressful situations? What will I do to fill my free time? Will I ever have fun again? Whatever your fears may be, they’re valid, and can be addressed and managed in healthy ways.

How to Understand and Overcome the Fear of Being Sober

Address the fear of change

The root of many common anxieties is the discomfort that is associated with change. Humans are creatures of habit, and have evolved to elevate awareness and senses when change is present. These mechanisms occur to protect individuals—almost like the way in which you might sense someone walking behind you.

To overcome this, you can practice acceptance and turn your worries over to your higher power or the collective wisdom of a higher counsel such as your sponsor or an AA or NA group. By practicing acceptance, you can find peace in knowing that you are powerless over drugs and alcohol, they have no place in your life, and beginning your recovery and sobriety is exactly what you are supposed to be doing, or rather, what you must do to make your life manageable again.

Embrace the opportunities

During early recovery, you may lose old friends that you were actively using with. You may be unable to patron the same places you once spent time in to have “fun”, and your idea of “fun” and leisure time will completely change. That’s okay and can be a beautiful thing.

Your recovery network, if utilized properly, can give you access to many individuals from all walks of life who genuinely understand your ailments and your accomplishments in sobriety. Find a group of individuals that uplift you and make you feel good about your recovery. The people you surround yourself with and reach out to can be an incredible support to you during this journey and the opportunities for new friendships and new fun is limitless.

Step out of your own way

The shame and guilt associated with active use probably held you back more than it helped you move forward in your life. During your early recovery, it can be tempting to return to ways of thinking that can put yourself directly in the way of your own growth. Don’t get in your own way. Take a deep breath and remind yourself of the serenity prayer each day:

Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change

The courage to change the things I can

and the wisdom to know the difference, just for today.

When you find yourself blocking your own path—reach out to someone in your support network. Talk through the things you are facing or the worries you have with someone who has experience or can provide you with insight.

Your recovery has the potential to help you be a better friend, partner, sister or brother, professional, volunteer, and more. As long as you allow yourself to take the necessary steps forward, you can take this growing opportunity and newly found free-time to improve your life in all areas. You may find that to grow, you have to take inventory and release unhealthy habits from your past. That is expected, and a sponsor or close friend in your program is a great source of support for you in doing so.

Find yourself

During active use, excitement and joy in your life probably came predominantly from your drug of choice. It’s time now to find what makes you feel alive again, because that’s where your passions exist. This might be reading, painting, exercising, playing with your kids, or learning new things. You may have to try out a few new things before you find your “aha!” feeling. That’s okay too! Rediscovering your personality in sobriety can be scary—but it can equally be a beautiful and exciting thing. Utilize your journal as you try out new things to reflect on how the experiences made you feel. Once you find something that you enjoy, make special time for it and do it to the best of your ability.

Learn to laugh

Finally, even in moments of fear, learn to laugh whenever you can, as often as you can. When you find yourself in the midst of your own anxiety, it can be overwhelming and all-consuming. You may tell yourself that dwelling on the things you can’t control, obsessing over the fears and the unknown—that’s easier than addressing them and finding a reason to laugh or smile. That’s simply not the case. Focusing exclusively on the negatives of your recovery can lead to extreme mental and physical discomfort, and may eventually lead you back to the feelings that drove you to use substances in the first place.

Find reasons to laugh and smile through gratitude each hour of your day. Though your journey through recovery is absolutely serious, try not to always take yourself so seriously. On your hardest days, you might try writing down two or three reasons you had to smile. When you imagine your reservations and fears, remember that they are feelings. You cannot always control how you feel, or when you feel fear, but you don’t have to let the feelings or fear control you. You CAN do this.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, ‘like’ the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.