We often expect those we serve to:

- be willing to make significant changes,

- sustain effort while making difficult changes that take time,

- and be willing to endure and benefit from practical lessons while making change.

But what about changes our organizations can make? Could some peer support of the organizational change process be helpful? Could some coaching tips in attempting system change toward a recovery orientation be useful?

This post will provide a partial overview of some aspects of organizational change, including contextual considerations, specific components of recovery orientation, the scale of change projects, and practical tips in making and supporting change. Examples of changes toward a recovery orientation will be included, along with citations for further study.

One contextual frame for the general guiding of organizational change is the notion of a helpful and effective “facilitating environment” (borrowed from Winnicott, 1974).

- For a clear picture of this, imagine an intentional ecological space within which there is effective nurturing and facilitation of personal development.

- Now make the relevant planning and related action for that support continuous down the following relevant layers, as outlined by Winnicott:

- the therapist and the laboratory (research efforts and findings),

- the therapist and their supervision (personal and professional development),

- the therapist and counseling (the context and provision of care),

- and finally, the patient and their home (as a system).

Changes consistent with Recovery Orientation can be made at the whole-organization level, entire programs can be modified, and specific practices within programs can be changed at the per-program level. Changes of this scale specific to Recovery Orientation have been achieved and written up for others to study (e.g. Boyle, M., Loveland, D. & George, S., 2010). In this type of planning, consider making changes that target either or both of:

- Disease Management (e.g. symptom suppression)

- Recovery Management (the pursuit of wellbeing).

Look for examples of change others have already made. Be sure to look for evaluation of their effectiveness, and for evaluation of the experience of those using the system. Nowadays, examples abound.

- Specific Disease Management efforts have been written up (e.g. Hamalainen, Zetterstom, et.al., 2018), as have patient experiences with disease management strategies (e.g. Nehlin, Carlsson, & Oster, 2017).

- Recovery Management efforts such as Recovery Coaching (White, 2004) have been archived, as have patient experiences with those kinds of strategies (Eddie, Hoffman, & Vilsaint, et. al., 2019).

Consider both the “New Paradigm” of Care and 5 Year Standard of Effectiveness.

- Practically speaking there is no such thing as “bad improvement”. In this way of thinking, virtually any starting point of change, and any amount of initial change is to be welcomed – both for the patient and for the system.

- Can we move toward that in our systems?

- In their article on a “New Paradigm for Long-Term Recovery” DuPont and Humphreys (2011) discuss the effect of: 1. services provided in the indigenous environment rather than a clinical setting, 2. a multi-year framework, 3. inclusion of person-centered goals, and 4. structured incentives that support positive change. These approaches have been found to be present in collegiate recovery programs, professional monitoring programs, and drug court models – probably going a long way toward identifying common factors for their shared effectiveness with disparate populations.

- Can we move toward that in our systems?

- Regardless of a person’s starting point, initial improvements, and incremental change, full-remission 5 years after the last clinical intervention is the standard for remission (when severe, chronic disease is the problem) and ultimate goal of comparison for eventual service effectiveness (DuPont, Compton, & McLellan, 2015).

- Can we move toward that in our systems?

Practical guidance in basic change principles for organizations and leaders to consider are also widely available. Some are general to any change effort, and some are specific to our work.

- General change related concepts and specific changes with practical relevance (increasing patient retention and decreasing wait times) have been archived for dissemination (e.g. McCarty, Gustafson, Wisdom, et. al., 2017). Practical axioms for leaders such as “When you think you’re going too slow, slow down” and “Don’t be afraid of change – you can always change back” can be very helpful in planning, guiding, and supporting change.

- Even multi-year, multi-program, organization-wide change efforts have been written up and evaluated (Loveland & Driscoll, 2014).

In reviewing these kinds of materials, you might find important changes consistent with Recovery Orientation can be innovated on a smaller scale as well. For example:

- Adding a technology solution blended with recovery coaching, both during and following residential treatment (Coon, 2013)

- Improving effectiveness at linking college-bound emerging adults with Collegiate Recovery Programs (Crowe, Hennen & Coon, 2017)

- Raising staff and student awareness of recovery support systems specific to undergraduate and graduate education, and that are available when later pursuing relevant professional licensure (Coon, 2015)

- Adopting a challenging best practice, such as transitioning to a tobacco-free treatment model (Coon, 2014; Martin, Lee, & Coon, 2018)

- Adding a coaching component and a technology tool for breath testing to an outpatient program (Hennen & Coon, 2020) to raise both retention and wellness.

Over the years, I’ve noticed it is helpful to have some support, encouragement, coaching, and guidance when attempting a change project, or moving a system toward a difficult goal. I have also noticed I’m in need of the same when coaching others in support of system improvement.

References

Boyle, M., Loveland, D., George, S. (2010). Implementing Recovery Management in a Treatment Organization. In Kelly, J & White, W. L. (Eds): Addiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research, and Practice. Pp. 235-258.

Coon, B. (2013). Center Uses Technology to Help Patients During and After Treatment. Addiction Professional. May 22, 2013.

Coon, B. (2015). Recovering Students Need Support As They Transition. Addiction Professional. 13(1): 22-26.

Coon, B. (2014). An Addiction Treatment Campus Goes Tobacco-Free: Lessons Learned. Addiction Professional. 12(1): 18-20.

Crowe, K., Hennen, B. & Coon, B. March 31, 2017. A Seamless Transition: Linking College-Bound Emerging Adults with Collegiate Recovery Programs. Recovery Campus Newsletter.

DuPont, R. L & Humphreys, K. (2011). A New Paradigm for Long-Term Recovery. Substance Abuse. 32(1):1-6.

DuPont, R. L., Compton, W. M. & McLellan, A. T. (2015). Five-Year Recovery: A New Standard for Assessing Effectiveness of Substance Use Disorder Treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 58:1-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.024

Eddie, D., Hoffman, L., Vilsaint, C., Abry, A., Bergman, B., Hoeppner, B., Weinstin, C. & Kelly, J.F. (2019). Lived Experience in New Models of Care for Substance Use Disorder: A Systematic Review of Peer Recovery Support Services and Recovery Coaching. Frontiers in Psychology. 10:1052. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01052

Hamalainen M. D., Zetterstom, A., Winkvist, M., Soderquist, M., Karlberg, E., Ohagen, P., Andersson, K. & Nyberg, F. (2018). Real-time Monitoring Using a Breathalyzer-Based eHealth System Can Identify Lapse/Relapse Patterns in Alcohol Use Disorder Patients. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 53(4):368-375. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agy011

Hennen, B. & Coon, B. (2020). Recovery Coaching, Breathalyzer Boost Retention in Outpatient SUD Treatment. Addiction Professional. September 23, 2020.

Loveland, D. & Driscoll, H. (2014). Examining Attrition Rates at One Specialty Addiction Treatment Provider in the United States: A Case Study Using a Retrospective Chart Review. Substance Abuse, Treatment, Prevention and Policy. 9(41). doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-9-41.

McCarty, D., Gustafson, D.H., Wisdom, J.P., Ford, J., Choi, D., Molfenter, T., Capoccia, V. & Cotter, F. (2017). The Network for the Improvement for Addiction Treatment (NIATx): Enhancing Access and Retention. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 88(2-3):138-145.

Martin, L., Lee, J. L., & Coon, B. (2018). Implementing Tobacco-Free Policies in Residential Addiction Treatment Settings. Physician Health News. 25 (2): 14.

Nehlin, C., Carlsson, K, & Oster, C. (2017). Patients’ Experiences of Using a Cellular Photo Digital Breathalyzer for Treatment Purposes. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 12(2):107-112. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000373

White, W. (2004). Recovery Coaching: A Lost Function of Addiction Counseling? Counselor. 5(6), 20-22.

Winnicott, D. W. (1974). Fear of Breakdown. International Review of Psycho-Analysis. 1(1-2): 103-107.

4 Reasons Why Acceptance is Essential to Your Recovery

“When I stopped living in the problem and began living in the answer, the problem went away. From that moment on, I have not had a single compulsion to drink. And acceptance is the answer to all my problems today. When I am disturbed, it is because I find some person, place, thing or situation – some fact of my life – unacceptable to me. I can find no serenity until I accept that person, place, thing or situation as being exactly the way it is supposed to be at this moment. Nothing, absolutely nothing, happens in God’s world by mistake. Until I could accept my alcoholism, I could not stay sober; unless I accept life completely on life’s terms, I cannot be happy. I need to concentrate not so much on what needs to be changed in the world as on what needs to be changed in me and my attitudes.” Alcoholics Anonymous (Big Book), 4th Edition, P. 417

The dictionary defines acceptance as the act of taking or receiving something offered–favorable reception; the act of assenting or believing: acceptance of a theory. The fact or state of being accepted or acceptable. You know what acceptance is, you can think through acceptance, but how can one really begin to practice acceptance in a way that supports their recovery?

Understand the importance of acceptance

Acceptance is necessary for your healing process. To practice acceptance, you must acknowledge all of the uncomfortable parts of yourself: your emotions, your thoughts, and your past.

Practicing acceptance is kind of like taking care of the dirty clothes hamper in your room. Throughout the weeks, you fill it with your clothes and it piles up. Work is tiring, cleaning the rest of the house is enough of a chore, and life keeps getting in the way. You know that the hamper is there, but you’ve been ignoring the real mess of clothes inside.

After enough time passes, you may even forget that you own some of the clothes at the bottom of that basket. Finally, the day comes when you acknowledge that the corner of your room is a real mess, you’re short on clothes, and it’s time to do laundry. As you take out each piece to wash them and hang them, you’re acknowledging the separate pieces of the mess, and accepting the situation and the tasks necessary to clean up—much like when you take your personal inventory and accept that you are imperfect, that there are parts of yourself and your psyche that you must work to heal.

Recognize the gifts of acceptance

As you grow and practice acceptance towards yourself, you’re able to be more accepting of others. When we make peace with the fact that everything is exactly the way it is supposed to be in the present moment, you can make peace with the variables of life around you, including other people. Compassion gives you the ability to grow in your own regard, while you also aid in other’s personal journey to self-acceptance.

Embrace the freedom of acceptance

Acceptance—though not an effortless task—is a freeing habit. Anxiety, stress, and depression can often be caused by the unwillingness to make peace with the terms of life. It is human nature to think that one can control and manipulate all of the components of reality, but you simply cannot. Peace and true serenity can only be found once you accept life on life’s terms.

As you find yourself troubled, upset by day to day struggles, situations, and others, remind yourself of the component of the serenity prayer in which you ask for the courage to change. When you’re feeling dissatisfied in those moments, figure out what you can change about yourself to accept the situations and people as they are in that exact moment.

After acceptance, comes gratitude

It’s important to remember that acceptance is not synonymous with tolerance. Acceptance is not the reluctant sigh at the end of a stressful day, nor the disgruntled statement, “it is what it is,” or “this is just who I am,” No, acceptance is total mindfulness grounded in reality.

Acceptance is the realization that your suffering, your anxieties, and stressors, are exacerbated in the moments in which you believe that you can successfully live your life or handle your recovery on your own terms. As you learn to accept and make peace with the way things are in this very moment, you step out of your own way and step forward on the path to growth.

The more often you practice acceptance, the more you will see that each moment has a purpose, a lesson to teach you, a reason for unfolding the way that it does. As you stay present in those moments and genuinely accept them, you may work to find ways to be grateful for life on life’s terms, further strengthening your recovery and improving your quality of day to day life.

***

For more information, resources, and encouragement, ‘like’ the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

“Life is pain…anyone who tells you differently is selling something”

William Goldman, The Princess Bride

Pain and addiction are intertwined. Prescribed medication for pain can be a route into addiction. In practice I regularly see people on multiple medications for pain, making treatment of their addiction challenging.

Last year Public Health England found that one in four people were taking ‘addictive’ prescription medicines. It looks like this is eclipsed by the situation in the US with a 2016 SAMHSA report stating ‘an estimated 119.0 million Americans aged 12 or older used prescription psychotherapeutic drugs in the past year, representing 44.5 percent of the population’. A third of this was pain medication.

This suggests there’s a lot of pain around. But pain needs to be addressed appropriately so it’s no surprise that there’s a lot of analgesic prescribing. It’s needed – right?

Well not so fast. The evidence for the benefit of opioids, for example, in chronic pain is pretty dire. Where studies have been done, the follow-up period is generally ultra-short.

So how confident can we actually be that opioids are both effective and safe in chronic pain? Well we can look to the highest standard of evidence, randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

See this flow chart for an analysis of the evidence base to 2012. It’s not particularly impressive to put it mildly. Yet millions of people have ended up on long-term opioid pain medication.

Now the UK National Institute for Health and Care guidance (NICE) has issued draft guidelines for the management of chronic pain. NICE aim to improve outcomes by setting out evidence-based guidelines. What do they say? Well, it’s pretty clear, not to mention stark:

Do not offer any of the following, by any route, to people aged 16 years and over to manage chronic primary pain:

- opioids

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- benzodiazepines

- anti-epileptic drugs including gabapentinoids, unless gabapentinoids are offered as part of a clinical trial for complex regional pain syndrome

- local anaesthetics, by any route, unless as part of a clinical trial for complex regional pain syndrome

- local anaesthetic/corticosteroid combinations

- paracetamol

- ketamine

- corticosteroids

- antipsychotics

This is a pretty revolutionary development and has set the cat somewhat amongst the pigeons. It’s still in draft, so may be modified, but by any measure it’s quite a change.

Reporting on the response to this of the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists who had concerns about category definitions of pain, the Pharmaceutical Journal said that the terminology was “highly confusing and damaging” and that there was a “serious risk” that the recommendations would be taken to apply to all chronic pain. It said that this “essentially” resulted in the guidance “not being fit for purpose”.

GPs have also expressed concerns around limited options with Pulse magazine reporting: ‘NICE has also missed the glaringly obvious contributing factor of social deprivation… chronic pain is almost overwhelmingly a problem of deprivation and despair.’

Given the number of people who present in primary care with chronic pain, I can understand those concerns. Although antidepressants are recommended in the guidance, alternative approaches to prescriptions take time and expertise to deliver. But what does this mean for all those people already on long term medication?

I am left wondering how we ended up with so many people on medication for pain with so little evidence of efficacy. My thoughts turn to Big Pharma and a commentary by Des Spence I read a few years ago in the British Medical Journal (restricted access):

“Research always reports underdiagnosis and undertreatment, never the opposite. Control all data and make the study duration short. Use the media, plant news stories, and bankroll patient support groups. Pay your specialists large advisory fees. Lobby government. Get your pharma sponsored specialists to advise the government. So now the world view is dominated by a tiny group of specialists with vested interests. Use celebrity endorsements to sprinkle on the marketing magic of emotion. Expand the market by promoting online questionnaires that loosen the diagnostic criteria further. Make the illegitimate legitimate”

Is he right?

I’ve been listening to a BBC podcast on my way to work this last couple of weeks which I’ve really enjoyed. Called Hooked, it’s about ‘all things addiction and recovery’ and is frank, funny, well-informed, upsetting, entertaining, resonant, authentic and powerful.

Melissa and Jade share their lived experience but also interview experts and others who are in recovery on a variety of topics including: rehab; relationships; relapse; codependency, porn and sex addiction; mental health; food; sober Christmas etc.

The presenters debunk myths, dissolve shame, educate and reduce stigma in with their unique blend of humour, curiosity and discussion. I recommend it.

It’s available for UK listeners from the BBC website, on the BBC Sounds app, and for people living elsewhere on Apple Podcasts.

Who are you?

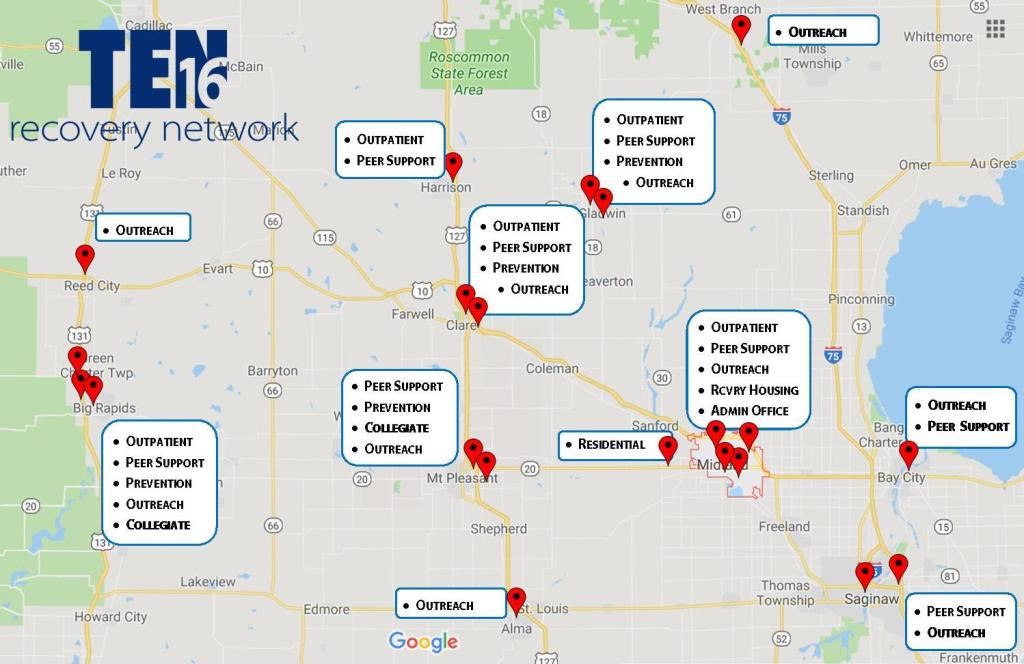

My name is Sam Price, I am the President/CEO for the Ten16 Recovery Network.

Tell me a little bit about Ten16 and your role there.

Alright, Ten16 is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year. I have been here since 2003, so about 17 of that has been on my watch. It started out as a halfway house by the local churches, way back in the day, and that migrated into residential treatment, and then we got into outpatient, and then we got into prevention and then we got into expansion. We started in Midland, Michigan. We are now in 10 different counties; providing outreach in emergency departments, we have residential, recovery housing, prevention, outpatient, drop-in centers, collegiate recovery on three campuses, prevention in four, five communities. So we try and have the full continuum, both vertically and horizontally, to work with folks.

How would you describe the communities you’re working in?

It’s a mixture of mostly rural. Midland is probably more of a suburban community. We started to work in Saginaw, which is more urban. So, it’s kind of a broad mixture, but I’d say mostly tilting towards suburban and rural.

Tell us about your professional experience in addiction and recovery, did you have any SUD experience prior to Ten16?

No, I didn’t. When I was selected to come to Ten16, my wife and I lived in Charlotte, Michigan. She was a teacher for the hearing impaired in Lansing, and I worked at a juvenile justice facility called Starr Commonwealth based in Albion, Michigan. Starr had about 200 residential beds for children that were in the juvenile justice system and had sites really across Michigan, in Ohio, with other community-based programs as well as other residential programs. I’ve always been in the helping field in one fashion or another but hadn’t been in SUD specifically. Midland was our hometown, and we wanted to get home. My wife’s mother was sick at the time. The opportunity came up to come to Midland at Ten16 and they invited me to work there, but it was really my first foray into SUD.

What are you most proud of in your professional life?

I saw that question before, and it really made me think…

I think probably the growth of the organization in these recent years, which has been pretty substantial. I think what has most made me proud is the fact that the staff have this willingness to join me to be bold and pioneer. For example, the thing that’s driving us right now is really kind of two ends of the spectrum in terms of how we view what we’re trying to bring to the community. In the one sense, we know that only 10% of the folks that struggle (with SUD) will walk through our doors or your doors on their own. So, we have intentionally said, “How do we put ourselves in places to get in front of the missing 90%?” And how do we engage them in conversations that may spark the beginning of recovery? That shift has attracted to us a lot of people who want to join us in the pursuit of that real… almost… raw recovery evangelism, if you will. So, in the last five to six years, we have ended up going from one hospital Emergency Department to ten; where we can sit with patients who are in the ED, maybe not even because of their SUD history. Maybe they’re there for a broken arm.

Here’s a great example of who we have a chance to talk with – there’s a time that my wife and I were in the emergency room for our own medical situation as a family. In the curtain right next door to where we were, [because that’s the only privacy that you have in the ED], there was a 72-year-old guy who was in there for some cardiac issues. He was waiting for the cardiologist to come, and the nurse came in to do the health history with him. As she’s talking with them, she finds out that he has been a widower for the last three years. He lives outside of Weidman, which is a town that has a population of maybe 1,000 at best. He’s not living even in the town itself, his kids to live out of the state. And, it’s just he and a cat and a six-pack every night.

Now he’s in the ED for heart issues. That’s what our advocates have an opportunity to do. The nurse can then turn to our staff and say, “Hey, I think you need to talk with this guy.” To us, we think there might be something about the six-pack a night that may be contributing to both his physical heart issues and his spiritual heart issues. We’re able to start that conversation that we never get if we just waited for him to walk through our door it. It’s easy to work with the person who shows up under the influence, or who shows up in the ED med seeking and stuff like that. We have so many rich opportunities to talk with other people who we would never normally be able to talk with and engage them in that change process.

On the flip side, we also know that we have to walk alongside somebody for five years before they can get that remission rate down to a truly sustainable level. How do we change our way of doing business and our way of offering services to folks that would cultivate that? We have totally re-engineered our outpatient practice so that it’s full drop-in. Any time you need to stop in and talk with somebody, you don’t have to have a scheduled appointment. You can stop in. The energy that brings to the staff, because we can have this community approach, has been incredible.

Ten16 is a place to start that journey. They can come to this rich, robust community, which then can introduce them to the natural (recovery) community that exists out beyond our professional walls. So, I think that direction, the energy, and the enthusiasm that the staff has brought to that movement would probably be what I would say is my proudest moment at Ten16.

What keeps you working in addiction and recovery?

It’s funny, people ask me that every now and then. When I was much, much younger, I had an opportunity to experience redemption on a personal level, because I was becoming a person that I didn’t think I was up here [pointing to his head – my self-perceptions weren’t in alignment with my actions]. When I really stepped back and saw where my life was heading, that’s not what I wanted to be. There was a spiritual awakening, if you will, that allowed me to experience this sense of redemption. The richness that that has brought (to my life) since then, is something that I want anyone who is lost and hurt and broken to have an opportunity to find. People that struggle with SUD need folks to help stand in the gap and say, “Hope is here and will be here and we’ll be here as long as you need… until maybe you can experience the same thing that I’ve experienced.”

How has the pandemic affected your work at Ten16?

Well, it certainly has put a cramp on community. We have to be uber-cautious for the safety of the staff and the safety of all the clients. There is a fair amount of concern that comes with that, which has a lot of really unhealthy consequences, particularly for the folks that we work with, because it breeds isolation. Isolation strips away the community that had been holding me (speaking as if a person in early recovery) together, and giving me that encouragement that I’ve been looking for in order to be able to keep moving forward every day.

A lot of that’s been stripped away… Yeah, I (speaking as if a person in early recovery) can get it through a virtual meeting, but that’s not the same as being face-to-face with other folks. So, the loss of that is hard. So, a lot of the coping mechanisms that I had have been stripped away from me, and haven’t been replaced in the same kind of meaningful way, and all new kinds of stressors are kinda coming along for us. So, Ten16 has seen an uptick in relapses. We’ve seen a huge uptick in the hospitals for alcohol-related events. They’ve (the hospital staff) seen a big uptick in methamphetamine and opiate relapses too.

So, as so many others in the press have said, it has a secondary impact when you roll into a pandemic with an (opiate) epidemic. It’s just not a good combination at all. The other thing is that, at the same time that it’s impacting all the folks that we serve, it’s impacting everyone that works here at the same time. It is not like there’s this separation. So, I’m trying to be present for the people who are coming to my care, and I still have to think about my wife and my kids–are they safe? and my extended family and my parents, are they safe? –none of us can escape that. It’s not just impacting the folks that we serve, it impacts all of us. So, it’s hard to turn that noise off, to be present, to help those that are looking to us for care at this time.

What, if any, long-term effects do you anticipate from the pandemic for the field?

It’s hard to know fully, because we’re still so early into it. I’m seriously afraid that it could be another 12 or 18 months that this is going to linger, if we have another wave that comes through. What I don’t know is what that’s going mean to treatment facilities. I’ve already heard that several dozen across the state have already closed, and another several dozen are teetering on the brink of closure.

Because of leaders trying to be safe in the way that they run their programs, there is limited access to treatment beds for those people that need a higher intensity of care. So, access is just going to continue to get crippled, which means getting in for timely service is going to be really, really problematic for folks. There are no easy answers to know how to fix that.

Even when you think of what happens out in the natural 12-step community, and the larger recovery community, even that has been impacted. Can there still be meetings indoors? Even so, you can’t have meetings of more than 10 people. Are there in places in our communities (like churches or community centers) that are even allowing 12-step meetings to be hosted because of some of the risks? So, there are so many ripple effects… I think we’re still just at the tip of the iceberg that we just don’t even know yet.

Again, that’s part of the problem, there’s so much uncertainty and ambiguity that is difficult for people to know how to navigate. There’s no end in sight to that, which gets back into that resilience depletion, right?

Have you seen any benefits or new opportunities in the pandemic?

Certainly the one that everyone turns to is the advent of telehealth, both for treatment services as well as recovery support, peer support opportunities. Again, it’s a blessing and a curse thing. Certainly, it fills in some of that access gap that [with a tool] we never had. Because we are forced to do it has made both parties–both providers and participants–more open to that. We find that, “Hey, this is can be a nice thing for me to be able to have my session, but I don’t have to worry about the headaches of transportation, because I don’t have a driver’s license, or I don’t have money for the bus or something along that line.” So, there are huge wins to that. I can go into rooms and I can find a meeting anywhere across the country. Those are wonderful things. There are limits to those things too, so there’s always the concern that when the pendulum swings or when the policy makes you say, “Oh, look at that.” All of a sudden it becomes a substitution for real community, because we’ve been able to develop this virtual community.

As it continues on, I think it will force us to continue to figure out how we can be more creative–how does it force us out of our boxes? For example, the regulations behind telehealth before were just Neanderthal. No one did it because the regs were so tight. Well, this kind of forced that change, and now that that horse is out of the barn, some of the people that hold the dollars have realized, “Okay, maybe we were a little bit too rigid, too cautious in some of the stipulations that were put into place.” Hopefully, that will allow for more creativity and more freedom, more flexibility to spark innovation.

I think we’re still trying to figure it out and figure out what the rules are, of how you can advance things safely within this… if we have to limit the number of people that are in a room, if we have to wear masks, if we have to be 6 feet apart….there are just so many new factors that we have to sort through, that I don’t think we know fully yet. It forces us to get out of our little cookie-cutter approaches that we’ve been so comfortable with–that has defined how we provide care–so I’m excited to see where it may lead us. All of a sudden we could have opportunities where, yes, we’re here in Midland, but all of a sudden maybe because of telehealth, we’re providing treatment and care and support to people in Ohio, or Wisconsin, or Seattle.

I think [peer support among providers via video conferencing] could be another good silver lining. We have gotten very comfortable doing this kind of stuff and feeling good with it.

We’re just talking about that mid-state meeting… if we could just have an open Zoom meeting for any provider that just wants to talk about the stresses, and the strains, and the struggles of doing virtual care, and all this sort of stuff, why wouldn’t we? Why couldn’t we? Maybe it’s breaking down some of those walls that have held us back.

If you were able to devote yourself to a fantasy project to improve treatment and recovery support, what would it be?

Sam: I think we still haven’t figured out as a system of care of how we go beyond maybe that first year of support. As people grow and mature in their recovery, those recovery needs change–how do we walk alongside them in meaningful, productive, and constructive ways?

We often talk within our organization–how do we help people move from recovery into wellness? As I’m getting some of these early recovery skills down, and I’ve figured out this part… but then there’s the next layer of my relationships or I’m getting my relationship with drugs in that right and healthy and place, but now it’s about, how do I find a career that brings me a feeling of meaning and purpose? Or, how do I get my relationships where that brings me meaning and purpose? How do I keep building upon that, in a way that I have constructed this robust life that we all kind of long for and dream for?

I’ve also seen some of those organizations that have micro-enterprises where they employ their own, and then those employees become the managers of different places, and some of those types of organic businesses or organic opportunities would be so cool to see develop.

Another odd little fantasy that I’ve had every now and then is, “I wonder what it would be like to have an assisted living facility for people in long-term recovery?”

I don’t know why, but [the idea has] always been one of those, “Huh, I wonder… as we age… would that be something?”

I don’t know why, but it’s always intrigued me about that kind of a community, and how would that look differently as we age, when typically medications are being poured on to us, and we’re losing a lot of our normal community… because my friends passed away, my spouse passes away, my kids move away. And, what do we do best as recovering people? Community.

What are the needs of somebody who’s had a long-term history or struggle with addiction? Maybe they have special medical complications that are kinda unique to that niche group of folks.

So again, it’s one of those things that I never spent a lot of time looking into it, but I’ve always been kinda fascinated about it. We’re all getting older!

(This post was originally published March, 2016)

(This post was originally published March, 2016)

There’s been a big change in the way professionals and advocates talk and think about drug and alcohol problems over the last several years.

On one end, we have professionals changing the classifications and mental models for substance use problems.

On the other end, we have recovery advocates changing the definition of recovery.

Before we dig into these changes, let’s start with a little background.

One attempt to classify drinkers

I’ve no doubt that there is a long history of classifying drug and alcohol users and, honestly, I’m not interested in digging into it right now. So . . . one easy to find attempt is AA’s. They were making no attempt to be authoritative–they were just trying to describe what they’d observed.

First, “normal” drinkers:

For most normal folks, drinking means conviviality, companionship and colorful imagination. It means release from care, boredom and worry. It is joyous intimacy with friends and a feeling that life is good.

Next, the various types of heavier drinkers:

Moderate drinkers have little trouble in giving up liquor entirely if they have good reason for it. They can take it or leave it alone.

Then we have a certain type of hard drinker. He may have the habit badly enough to gradually impair him physically and mentally. It may cause him to die a few years before his time. If a sufficiently strong reason – ill health, falling in love, change of environment, or the warning of a doctor – becomes operative, this man can also stop or moderate, although he may find it difficult and troublesome and may even need medical attention.

But what about the real alcoholic? He may start off as a moderate drinker; he may or may not become a continuous hard drinker; but at some stage of his drinking career he begins to lose all control of his liquor consumption, once he starts to drink.

To review, they seemed to identify 4 types of drinkers:

- normal drinkers,

- people who find that they have been drinking more than they want to and choose to cut back or quit,

- people whose drinking gets them into trouble and may need some professional help to moderate or quit, and

- alcoholics who have lost control of their drinking for whom abstinence is the only solution.

While these distinctions were observed by lay people in the 1930s, for decades, drug and alcohol professionals too frequently failed to recognize these differences and often treated types 2 and 3 as though they were a type 4.

The DSM – From Abuse/Dependence to a Continuum

In 1980, the DSM-III created the diagnosis of substance “abuse” (similar to AA’s type 3, but may include some type 2 drinkers) as separate from substance “dependence” (similar to AA’s type 4 but, unfortunately, still captured many type 3s). These categories continued through the DSM-IV.

In 1980, the DSM-III created the diagnosis of substance “abuse” (similar to AA’s type 3, but may include some type 2 drinkers) as separate from substance “dependence” (similar to AA’s type 4 but, unfortunately, still captured many type 3s). These categories continued through the DSM-IV.

Unfortunately, it took too much time for professionals to catch up. (Since Dawn Farm began providing outpatient services in 2000, we have offered 2 “tracks”. The first is for people who meet DSM abuse criteria and/or prefer moderation as a goal. In this track, clients choose moderation or abstinence as their goal. The second track is for people with the more severe and chronic substance problems and abstinence is the goal.)

Over time, it’s my impression* that most professionals did catch up. These categories seemed to become more widely used and shaped care. These were conceptualized as different in kind rather than a difference in severity. Most people meeting “abuse” criteria will never progress into “dependence” and moderation being a perfectly appropriate goal for patients diagnosed with “abuse.” (* My impression is based on professional publications, conference presentations and my admittedly regionally limited interaction with other professionals. This impression is disputed by others and I’m open to the suggestion that many professionals persistently failed to make these distinctions.)

In 2013, the DSM 5 eliminated abuse and dependence, combining them into a single disorder measured on a continuum from mild to severe.

This means that the new diagnostic manual conceptualizes types 2, 3 and 4 as different in severity rather than a difference in kind.

Shifting Definitions of Recovery

This coincides with advocacy efforts that had been seeking to broaden the definition of recovery. In 2001, groups like Faces and Voices of Recovery (FAVOR) formed and sought to include people using non-12 step approaches and people on maintenance medications like methadone under the banner of “recovery.” It was my impression that, at this time, the concept of recovery was confined to those recovering from the disease of addiction.

By 2011, recovery advocates had embraced what has become an important talking point, that 23.5 million Americans are in recovery.

According to the new survey funded by OASAS, 10 percent of adults surveyed said yes to the question, “Did you once have a problem with drugs or alcohol, but no longer do?” – one simple way of describing recovery from drug and alcohol abuse or addiction.

10%? . . . 23.5 million? Those numbers are a powerful advocacy tool. However, to me, this constituted an important transition. This expanded the label of recovery to AA’s type 2 and 3 drinkers, meaning that groups like FAVOR were now applying the label of recovery to people who had short-lived and mild substance use problems, and people who are using substances non-problematically.

To me, the de-coupling of recovery and addiction seems like a very important development.

Not an argument for “dependence”

Dependence was far from perfect. This is not an argument for a return to the abuse/dependence model. (Though I will argue that we should return to conceptualizing as addiction as a different kind of problem from low to moderate SUDs, rather than a different severity.)

Let’s start by stating that addiction/alcoholism is the chronic form of the problem is primary and characterized by functional impairment, craving and loss of control over their use of the substance.

Problems with the categories of abuse and dependence include:

- Dependence has often been thought of as interchangeable with addiction/alcoholism, but this is not the case.

- Dependence criteria captured people who are not do not have the chronic form of the problem. We know that relatively large numbers of young adults will meet criteria for alcohol dependence but that something like 60% of them will mature out as they hit milestones like graduating from college, starting a career or starting a family.

- Dependence criteria captured people who are not experiencing loss of control of their use of the substance.

- The word dependence leads to overemphasis on physical dependence which, in the case of a pain patient, may not indicate a problem at all.

- The word abuse is morally laden.

- For me, there are serious questions about whether abuse should be considered a disorder at all.

Several of these problems are related to doing a poor job in distinguishing which kind of user the patient or subject is.

The abuse/dependence model fell short in distinguishing between kinds of users. Rather than taking a step forward in distinguishing between the kinds of users, the continuum approach implies that there is only one kind with different levels of severity.

Does it really matter?

Reasonable people can disagree, but I find this problematic for a few reasons.

Stigma

I tend to believe that failing to distinguish between kinds of problem users will actually add to stigma. It will perpetuate the conversations that sound something like, “Greg, when your Uncle Bob was in the Navy, he drank too much and got into some trouble. Then he had kids and knocked it off. Why can’t you just do the same?” The reason they can’t do the same was that Uncle Bob was a problem drinker and Greg is an alcoholic.

Non-alcoholics using the drinking experience of non-alcoholics (themselves or others) to understand the experience of alcoholics only increases stigma.

It’s not a different degree of the same thing. It’s a different kind of thing.

In my experience, it’s only when people understand that it’s a different kind of thing—that the experience of the alcoholic cannot be understood by reflecting on your own experience of drinking too much in college—that stigma can be challenged.

Disease and non-disease under the same diagnosis?

The continuum approach becomes especially troubling when you think about the idea of giving people with low severity SUDs and people with the disease of addiction the same diagnosis, only with different severity ratings.

There’s little doubt that large numbers of young people on college campuses meet diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder under the DSM 5. I doubt anyone would argue that all of these young people have a disease process? Even a mild one?

This seems likely to undermine the acceptance of addiction as a disease. Not just by the public, but also by insurers and policy makers.

Others are more concerned, arguing that abuse should be thought of as a behavior and dependence as a disease, and by combining them it becomes easier for payers to deny clinically appropriate care. Even worse, it might signal a shift to the idea that any professional with “behavioral” health training would be eligible.

One frequent example of how this conceptualization undermines the disease model is one of last year’s most popular posts.

In arguing that the causes of addiction are environmental (non-nurturing environments) and social (lack of connection) Johann Hari pointed to returning Vietnam vets discontinuing heroin without treatment as proof that addiction is not a disease.

However, these Vietnam stories often ignore an important fact:

“. . . there was that other cohort, that 5 to 12 per cent of the servicemen in the study, for whom it did not go that way at all. This group of former users could not seem to shake it, except with great difficulty.”

Hmmmm. That range….5 to 12 percent…why, that’s similar to estimates of the portion of the population that experiences addiction to alcohol or other drugs.

To me, the other important lesson is that opiate dependence and opiate addiction are not the same thing. Hospitals and doctors treating patients for pain recreate this experiment on a daily basis. They prescribe opiates to patients, often producing opiate dependence. However, all but a small minority will never develop drug seeking behavior once their pain is resolved and they are detoxed.

My problem with all the references to these vets and addiction, is that I suspect most of them were dependent and not addicted.

So…it certainly has something to offer us about how addictions develops (Or, more specifically, how it does not develop.), but not how it’s resolved.

How useful is it as a diagnostic category?

What’s the purpose of a diagnosis?

Isn’t it to give us a way to think about the causes, course, symptoms and treatments for an illness?

In plain language, a diagnosis is supposed to help us think about, talk about and understand what happened, what’s happening, what’s likely to happen, what will help, what is unlikely to help and what might be harmful.

What do someone with the disease of addiction and someone with a low severity SUD have in common? Do they have anything in common other than some harms (symptoms)? I can think of very little.

When we have one diagnosis that includes problems with radically different causes, courses and treatments, what use is it?

Really, it’s hard for me to see how this category would give helpers any insight into the patient’s experience or help in developing policy responses.

It feels a little like a diagnostic category of “respiratory disease.” It could be acute or chronic; it could be viral, bacterial, congenital, malignant or benign; it could be mild, moderate, severe or terminal; it could require aggressive and invasive treatment or no treatment; it could be progressive, nonprogressive or relapsing and remitting; etc.

Combining addiction and problem use into one continuum seems to like it brings confusion rather than clarity to understanding what happened, what’s happening, what’s likely to happen, what will help, what is unlikely to help and what might be harmful.

Will it eventually undermine advocacy efforts?

Doug Rudolph, of the advocacy group Young People in Recovery, suggested that messaging using SUDs as a category is misleading, undermining integrity and credibility.

I believe that we need to stop merely talking at the public, using the same language, playing to emotions, overgeneralizing data, and commanding them to agree with us, no questions asked. We need to stop using oversimplified, polarizing language that basically characterizes anyone who struggles with drugs and alcohol as suffering from a life-long, incurable, chronic brain disease because that will not, and hasn’t yet, resonated with the silent majority of America. We need to stop skewing statistics to further an agenda, unlike how the above cited statistic is often used, because that calls our integrity and credibility into question. Rather, we need to start digging deeper to develop an effective method that will bridge the gap and reconcile the inconsistencies between messaging and reality. And most difficult of all: we need to be objective.

He added that it risks drawing the attention of advocates away from important questions:

To do this, we need to start asking more nuanced questions that the recovery community has historically glossed over, and which many people believe are taboo to even ask or mention.

For example, while there is a significant difference between a free-of-charge mutual aid, community-driven support group and treatment, should treatment centers be employing and profiting off a method of treatment that a person could receive for free down the street? Should treatment centers be held to a higher, better regulated standard? Do we (as advocates) have a duty to constructively criticize the methods of treatment by which Big Treatment earns profits? While people attending community-driven support groups can do whatever they wish to help themselves maintain recovery (as long as it’s legal), how can we blame Americans at large for not believing that addiction is a bona fide medical disease when the oldest and most popular form of addiction treatment, for which people (or insurance companies) pay big bucks, relies on prayer, character defects, and admitting wrongs? How many other medical diseases or psychiatric disorders are primarily treated this way? Would it be appropriate to treat schizophrenia, PTSD, or diabetes this way? What’s the difference? Do people notice or think about this? Would acknowledging this and incorporating it into our messaging hurt or help our advocacy efforts?

Will it inflate “addiction” rates?

These changes were intended to clear up language problems, specifically the conflation of dependence and addiction leading to “false positives” for addiction. Looks like the DSM-5 is causing its own language problems before it’s even adopted. [emphasis mine]

Many scholars believe that the new manual will increase addiction rates. A study by Australian researchers found, for example, that about 60 percent more people would be considered addicted to alcohol under the new manual’s standards. Association officials expressed doubt, however, that the expanded addiction definitions would sharply increase the number of new patients, and they said that identifying abusers sooner could prevent serious complications and expensive hospitalizations.

What’s the solution?

It’s my opinion that thinking and talking about high severity SUDs and low severity SUDs as different kinds is important for good treatment and good advocacy.

Unfortunately, that means a lot more work for treatment providers and researchers. And, less impressive numbers for recovery advocates.

Why would it be more work for treatment providers and researchers? Because trying to sort type 3 and type 4 is not easy and takes time.

For example, when I have a young adult who meets criteria for alcohol dependence, I have to work with them to figure out if they are a type 3 (Meaning moderation might be a good goal and that might be achieved through education, motivational interviewing, contingencies or help addressing other problems leading to excessive drinking.) or a type 4 (Meaning abstinence should be the eventual goal and they may require specialty treatment followed by long term monitoring and support to achieve that goal.).

I’ll often have a conversation that sounds something like this:

One of the things we’d have to sort through is the kind of alcohol problem you have. There are 2 big categories. The first is the progressive, more severe and chronic type–alcoholism. The second is a lower severity problem that people often mature out of with little or no help, often making the change after some consequence or because of a life transition like graduating or parenthood. Research suggests that something like 60% of young people meeting criteria for alcohol dependence fall into the second category. The kinds of things that suggest someone is likely to fall into the first category are use of other substances, loss of control, euphoric recall of first drug contact, atypical tolerance, continued use despite growing consequences and family history.

Of course, it may take some time and some trial and error to agree on whether the patient is a type 3 or type 4. This conflicts with the goals of DSM writers, researchers, insurers and too many practitioners, but I don’t see a way around it.

Another Vietnam cohort?

This entire issue could be of significant consequence as the current opioid epidemic continues to unfold.

Let’s take a look at comments from the researcher who did the returning veterans study and how it has been misunderstood:

The argument that addiction in Vietnam was a response to war stress, and therefore remitted on exit from the Vietnam war theatre, is still frequently cited as though it were self-evident, because it sounds so plausible. Yet accepting this argument is difficult in the face of the facts. Heroin was so readily available in Vietnam that more than 80% were offered it, and usually within the week following arrival. Those who became addicted had typically begun use early in their Vietnam tour, before they were exposed to combat. Further, the dose-response curve that is such a powerful causal argument did not apply: those who saw more active combat were not more likely to use than veterans who saw less, once one took into account their pre-service histories. (Those with pre-service antisocial behavior both used more drugs and saw more combat. Their greater exposure to combat was presumably because they had none of the skills that kept cooks, typists, and construction workers behind the lines.)

These men were in an environment where it was readily available and presumably less stigmatized, leading to high rates of social/recreational use. This social/recreational use led to high rates of dependence, giving the impression that they had the disease of addiction when, in fact, it appears that only a minority did. This misunderstanding leads to false understandings about the causes, course and treatment required for addiction. These false understandings shape research and public understandings of the problem and solutions.

When one considers this Vietnam story along side what we know about young people meeting criteria for alcohol dependence, it opens the door to some frightening possibilities for this opioid epidemic.

Given the dramatic increases in opioid misuse, is it possible we’ll see a large numbers of people presenting with opioid dependence who are not actually addicted?

If so, will each group get the right treatment for their problem? Will people with opioid-dependence-but-not-addiction be given treatment that focuses on things like maintenance medication, lifelong abstinence and recovery maintenance, when something that looks more like an acute care model would be more appropriate?

Will the research done on treatment provided during this epidemic make any attempt to distinguish between types and each type’s response to various treatment interventions? I wonder if we’ll find that the the opioid-dependent-but-not-addicted group responds well to office-based buprenorphine treatment and are restored to a good quality of life, while addicted groups get stuck or have poor retention and continue to use other substances.

A Sober Mommies Contributor is most often a non-professional – in and out of recovery – with reality-based experience to share about motherhood & active addiction, the multiple pathways to recovery, or a family member’s perspective.

In celebration of National Recovery Month, Fellowship Hall is highlighting the stories of some of our incredibly inspiring alumni and staff members on social media and here on our blog. It is our hope that in sharing these stories, we break the stigma surrounding drug and alcohol addiction. With knowledge, we can advocate for the proper treatment of ourselves and loved ones that may struggle with the disease.

***

Not everyone can pinpoint the beginning of their struggle with drugs and alcohol. Robert P, however, recalls a classmate’s simple question that would change his life forever, “Have you ever gotten high?” While growing up in Mt. Airy, North Carolina, Robert says he felt as though he didn’t “fit in” with his peers. To combat those feelings of worthlessness, he lied and said that he had used before. “I couldn’t wait to use in hopes that drugs would fill the void,” Robert said. Little did he know, that simple “yes” would begin a battle with substances that would lead him to some of the lowest points of his life.

Robert says that he didn’t get high the first two times he used, but that didn’t stop him from using the third time–which ultimately “did the trick,” he says. “I got as high as a kite and bought into a lie that day that the hole I felt was finally gone. From that point forward my entire life was about getting high. Using substances created an illusion of feeling fulfilled, the obsession and compulsion of addiction took off like a jet leaving the planet.”

“Once I started using, I couldn’t stop, or rather, I stopped when things got bad but I couldn’t stay stopped,” Robert explained. As others in their early 20’s graduated college or started their careers, he spiraled down into what he describes as the lowest point of his life. By 24, he had suffered through five drug overdoses and served three and a half years in prison. One of his overdoses required him to be resuscitated three times. After a drug seizure in October of 1988 he was crushed spiritually, mentally, and emotionally he said.

Robert went on to get a job at a large textile corporation. He dedicated massive amounts of time and effort to his work, determined to move up in the company. His hard work did not go unnoticed–finally, he was selected as employee of the week. Unfortunately, Robert said that as the employee of the week, he mostly remembers laying on the floor with his forehead split open from seizing from overdose and passing out into a knitting machine. “The paramedics were hovering over me, asking me what my name was and I didn’t know. That episode landed me in a treatment center. I cried on the way there and told my mother I hoped there was another way to live, because I was sick of the mess my life had become,” he said. After entering treatment he would go on to relapse 14 times in 22 months. It wasn’t until he accepted a complete and total defeat that he surrendered to recovery that it would finally stick for him.

“I didn’t understand that self-will and self-centeredness were at the core of my destruction,” Robert admitted. “I learned that just quitting does not work. The only thing that stopped addiction from running over me is recovery, which for me, is complete abstinence and spiritual growth. I needed an active recovery program in order to manage addiction. I had to surrender. I used to think surrendering meant just admitting and accepting that I was an addict, but I missed the part about surrendering to recovery…like having a sponsor, a network of support, going to meetings, and living the NA way instead of my way.” Robert says that after this realization and dedication to the full recovery process, his life began to improve vastly.

“I told God, ‘I am going to do this 12-step program and if You ever want me to do something different, You let me know’,” Robert recalls. “For the next 25 years, I completely gave myself to the Twelve-Step way of life but, sure enough, the day came that God let me know He was calling me. By His grace, I’m dedicated to living a Christ-like life by striving to prepare to help others to do so in the wonderful world to come. And, by His grace, I am blessed to have celebrated 30 years clean on August 25th of this Year.”

Robert says he once heard a minister deliver a message about living life the give way versus the get way and it made a huge impact on how he lives today. Robert looks for opportunities to give to others by sharing the wisdom he’s learned along the way. In 1998, he joined the staff at Fellowship Hall as the Manager of the Gateway House. Now the Gateway Program which has two houses Gateway House and Zander’s Place that offers individuals in recovery structure, accountability, and support in the early stages of their recovery. He is deeply passionate about his work and over the years, he says, he has been blessed with the opportunity to inspire and encourage hundreds of men who have come through the Gateway transitional housing program.

Robert has made it clear that his wife Angela is his angel in recovery and in life. Robert is very grateful for all the support from his loved ones and the recovery community, Robert has had the opportunity to leave a lasting impact on everyone that he interacts with. If you’re lucky enough to run into him at Fellowship Hall and ask how he’s doing, he’s always quick to tell you, “I’m happy to be alive.”

For more information, resources, and encouragement, ‘like’ the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

The SMART Community had the opportunity to hear from Board President Bill Greer and Executive Director Mark Ruth as they shared their perspectives on what the SMART community has accomplished in 2020 and where we are headed in 2021.

Support SMART’s Recovery Month Fundraising efforts

Download the PowerPoint presentation

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Programs closing

This story about the impact of COVID on the treatment industry grabbed my attention:

At the beginning of 2020, addiction treatment was a solid, growing industry, with 15,000 providers, $42 billion yearly revenue, and a projected 5.2% annual growth. Then Covid-19 hit.

By the summer, the industry had lost $4 billion in revenue, and about 1,000 providers—and that’s just the beginning. According to the latest survey of the industry, published Sept. 9 by the National Council for Behavioral Health (NCBH), which represents about 3,000 mental health and addiction treatment providers, 54% of organizations have closed programs and 65% have had to turn away patients. As a result, nearly half have decreased work hours for staff, and over a quarter had to lay off employees.

My first reaction was ambivalence–there are a lot of bad actors and profiteers in the industry, maybe this will push some of them out.

Not so fast.

While a majority of rehabs have been hit hard, there is a specific group that is already seeing the effects of increased demand: High-end services. These programs have luxurious settings and amenities, and fewer patients, which makes it easier to prevent possible exposure to Covid-19. “We provide premium services, and that’s been the saving grace in this,” says Tieman.

His organization’s three premium programs—two in Pennsylvania, and one in Florida—have stayed at capacity through the pandemic, he says, because patients with the financial wherewithal to check into a premium residential treatment programs have continued to do so as they face a greater risk of substance abuse. Compared to the general programs, which costs $35,000 per month and is typically paid for with a combination of insurance and financial aid, the premium programs are $75,000 a month, with no discount offered, and though they have fewer patients, the programs have been helping the organization minimize the losses through the crisis.

Worse yet:

Many smaller providers have struggled to keep their businesses going, and in some cases, have shut down entirely. This is especially true for facilities funded primarily through public insurance, which have a harder time getting sustainable reimbursement rates and were already in the most tenuous shape prior to the pandemic. These are providers that tend to serve the most financially vulnerable.

While these programs get a lot of attention for quality issues, many of them do provide quality services and function as important safety nets for our most vulnerable community members.

Growth sectors

While we witness the demise of some portions of the industry, there have been changes to increase access to other types of care–primarily telehealth and buprenorphine prescribing.

Godinez’s process was almost impossibly simple: She texted her doctor and a drug counselor, who briefly evaluated her via FaceTime and wrote a prescription that she filled at a Walgreens around the corner from her Hendersonville, Tenn., home — a process that, until March, would have been largely illegal.

…

Now, as they wield unprecedented freedom to prescribe addiction drugs by telemedicine and evaluate patients by phone, many doctors and advocates say they’re unwilling to relinquish that flexibility without a fight. Already, there is a burgeoning movement to keep many of the new policies in place permanently. Many treatment providers across the U.S. have said publicly that the new status quo represents long-sought change that could positively transform patient care for decades to come.

“You can’t put the genie back in the bottle,” said Stephen Loyd, a Tennessee addiction doctor who treated Godinez and who once served as the state’s drug czar. “This is how it needs to be — always.”

The pandemic is also amplifying calls to eliminate the “X waiver” that requires physicians to receive 8 hours of training before prescribing buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorders.

Due to the COVID-19 emergency, the US federal government has temporarily waived the initial in-person assessment for initiation of buprenorphine and has increased flexibility for the dispensation of take-home methadone. These changes allow prescribers to initiate buprenorphine treatment remotely. These changes are welcome, and the federal government should do more along these lines. All providers with prescriptive authority should be allowed to prescribe buprenorphine, which could be achieved by removal of the requirement for a US Drug Enforcement Administration ‘X’ waiver. Emergency funding for buprenorphine and methadone should be released so that patients who are unable to afford these treatments, particularly in states without Medicaid expansion, can access treatment. Importantly, the structure of treatment settings themselves could increase infectious spread without thoughtful redesign. Limiting requirements for frequent in-person visits, facilitating remote healthcare delivery and providing these healthcare providers with appropriate protective equipment would be paramount to preventing the further spread of SARS-CoV-2.

The regulatory context

Meanwhile, I was talking with a friend who works for an FQHC (Federally Qualified Health Center) about their substance use disorder services. They have a fairly robust MOUD service, prescribing a lot of buprenorphine and some extended-release naltrexone.

I asked about other services for addiction. He reported that they are unable to provide addiction treatment because they are not licensed for it.

Let that sink in.

The hurdle for prescribing buprenorphine is an 8 hour training for the prescriber (24 hours for nurse practitioners and physician assistants). For outpatient group and individual counseling, it’s licensure as a specialty program.

Further, we’re seeing the implementation of higher regulatory standards for addiction treatment. This is in response to quality problems in many programs. It’s not a bad thing, if done properly.

So, we got a push for the deregulation of medications for opioid use disorders (MOUD) and a push for increased regulation of other forms of treatment.

Should we care?

As this blog has pointed out over the years, diversion of buprenorphine is a reality.

Most advocates quickly respond that illicit use of buprenorphine is for non-medical self-treatment and avoidance of withdrawal by people with opioid addictions. Further, that this is proof that buprenorphine is over-regulated.

A recent story in Filter explores the emergence of buprenorphine misuse by people who were not previously or currently using other opioids.

There has been an abundant market for Suboxone on the streets of Kensington for several years, as I’ve reported for Filter. And some municipalities, including Philadelphia, have begun dropping criminal penalties for possession without a prescription. But until recently, I had never met a Suboxone user who didn’t previously or concurrently take another opioid.

...

The reasons for its emergence are complex, but a significant factor is the ease with which Suboxone, thanks particularly to its sublingual film form, is smuggled into jails and prisons—and then concealed and divided once inside. Together with synthetic cannabinoids (called “deuce” on Philly street corners), Suboxone is anecdotally the favorite drug in Philadelphia County’s carceral settings.

…

Once inside, the strips are cut into smaller pieces which are taken orally, or else dissolved in water and snorted. The euphoric effects of buprenorphine on a person without opioid tolerance are indistinguishable from other prescription opioids. Regular use can lead to physical dependency. So released people, as they have recently described to me, have been returning to the streets with a taste for the orange films, which are sold up and down Kensington Avenue and on street corners across Philadelphia.

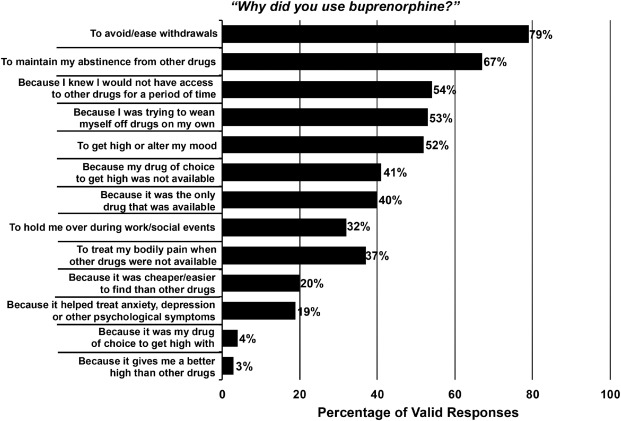

A more scholarly look at non-prescription use of buprenorphine found that the most commonly cited reasons for non-prescription use were self-treatment and avoiding withdrawal. However, more than half (52%) of respondents reported using it to get high.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Chilcoat HD. Understanding the use of diverted buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Dec 1;193:117-123.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Chilcoat HD. Understanding the use of diverted buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Dec 1;193:117-123.

While it hasn’t been widely reported, this has been known for years. My first post on the problem was in 2006. Further, failure to acknowledge the problem has the potential to create serious barriers for many people with addiction seeking recovery. For example, mandates that all recovery homes allow opioid agonists like buprenorphine. (Those SAMHSA guidelines were not mandates, but mandates have been discussed at the state and regional levels. The first step is making funding of services contingent on integrating opioid agonists into all housing programs.)

What we miss when we focus on opioid treatment and recovery

(This section is a post from September 17th, 2019)

Fortunately, there’s been growing concern that advocates, policy makers, and media have to narrowly focused on the opioid crisis. Up to this point, it hasn’t reached the level of media coverage.

USA Today is one of the first to publish an article that explores the limitations of the nation’s focus on opioid treatment and recovery:

More than eight years into his opioid-addiction treatment, Paul Moore was shooting cocaine into his arms and legs up to 20 times a day so he could “feel something.”

The buprenorphine he took to quell cravings for opioids couldn’t satisfy his need to get high. Moore said he treated himself like a “garbage can,” ingesting any drug and drink he could get, but soon enough, alcohol and weed had almost no effect unless he vaped the highest-THC medical marijuana available.

Cocaine, however, especially if it was mainlined — now that could jolt him from his lifelong depression to euphoria.

The article provides several important messages:

- The importance of addiction treatment over opioid use disorder treatment for many (if not most) patients.

- Along similar lines, messages about opioid recovery can be misleading for patients, families, and communities.

- These issues raise the importance of clarity about the boundaries of recovery. For example, were these people in recovery when they were in opioid use disorder treatment and reduced or quit using opioids, but were still using cocaine and experiencing poor quality of life due to untreated addiction? (This would have been an uncontroversial and easy question to answer just a few years ago. Today, there are many saying that any movement toward wellness or participation in harm reduction is recovery.)

- The article also highlights what gets missed when agonist treatments (buprenorphine and methadone) are described as the most highly effective and highly successful treatments without more context. They rarely answer the question, effective at what? (This isn’t saying that these medications aren’t useful or don’t have a place in care. Rather, it’s important that journalists and experts do not oversell their evidence for effectiveness.)

Failure to clarify and communicate these messages are likely to result in increased stigma for addiction and recovery.

Rather than communicating that addiction is a treatable illness, the unintended message will be that addiction more closely resembles a chronic disability than a treatable illness that has a good prognosis when the patient receives treatment of adequate quality, duration, and intensity.

This century’s first wave of recovery advocacy was built upon the message that we can and do recover when we get the right help and support. In this context, recovery meant something resembling the Betty Ford Consensus Panel definition:

Recovery from substance dependence is a voluntarily maintained lifestyle characterized by sobriety, personal health, and citizenship.

The traditional understanding of addiction recovery alludes to the restoration of people in their families, communities, and to a life in alignment with their goals and values.

Adjustments to that understanding are likely to result in readjustments in the public’s attitudes, which are eventually likely to result in readjustments in policy.