This is the first of what I hope to be a regular series of interviews with addiction professionals about their work and how the pandemic has affected it.

Who are you?

My name is Bill Stauffer, I am a person in long term recovery living in eastern Pennsylvania. I have worked in and around the substance use care system for over thirty years in many different capacities. Recovery is something I am very passionate about. When I am not working in and around our care system, I am hanging out with my wife Julie who is an artist and our two dogs or out in the woods looking for birds or taking photographs.

What do you do professionally?

Over the last 30 years, I have run public funded outpatient and residential treatment programs and provided direct care to many people. I am also a trainer an educator and a writer. Currently I run PRO-A, the statewide recovery community organization of Pennsylvania. Our organizational mission is to: “mobilize, educate and advocate to eliminate the stigma and discrimination toward those affected by alcohol and other substance use conditions; to ensure hope, health and justice for individuals, families and those in recovery.” I am deeply committed to it.

Do you have any personal interest in addiction and recovery that you’d like to share?

Addiction and recovery have been the primary focus of my life work. Addiction has taken more family and friends from me than every other condition combined. At the same time, I have seen and been honored to be a part of the recovery experience for hundreds of persons over the years. I believe recovery can change lives and at times we can become “better than well.” We need to expand access and improve retention in recovery services, we can dramatically transform our communities and save vast resources.

Tell us about your professional experience in the area of addiction and recovery.

I have done many jobs in our care system from entry level work to program administrator. This has been an important trajectory for me. It has exposed me to program founders of our care field. As a result, I have a very well-rounded view of what this service field is like from a myriad of perspectives, most importantly from the ground level, including client because that is where my story started.

What are you most proud of?

Recovery advocate of the year award at America Honors Recovery and being honored with people like Don Coyhis of White Bison rank pretty far up there for me. But if anything, I am most proud that I have been able to do this work and to be of service to others along the way. David Best, the researcher from the United Kingdom calls recovery “the contagion of Hope.” Recovery spreads through our communities, saves lives, restores families and heals communities. This is what I have seen in my years of service and I am deeply grateful to be a part of the process and to see the positive, ripple effect that recovery has had on our communities. As discussed in the blog post Custodians of Recovery blog post with Bill White the work is about servant leadership. I am grateful for the ability to “pay it forward” and expand access to recovery as a central focus of my efforts.

What keeps you working in addiction and recovery?

A formative experience for me was spending a great deal of my time working in the field with early pioneers and people who founded programs in the late 1960s and early 1970’s. When they started their work to create a care system, care was non-existent. Prison, or psychiatric care with electro-shock therapy or frontal lobotomies was the standard of care in the 1960s. My first introduction to people who envisioned a public SUD care system was when I was a client in the mid-80s. The care I got in the 80s was entirely unavailable just 15 years earlier and was largely considered a near impossibility to create. I am alive because they took their seemingly impossible vision and made it a reality for me and millions of others. I see the importance of paying that forward and taking care in a direction that supports long term recovery. I would point to a conversation I had with Dr Robert DuPont on the five year recovery paradigm as the area of focus for my efforts in a broad sense.

How has the pandemic affected your work?

We are in the early stages of understanding the long-term ramifications of COVID-19 and how it will impact us. There is a significant increase in resumption of use within the recovery community and addiction related deaths. Recently testified in Pennsylvania about COVID-19 and its impact on our care system in front of our State House Human Services Committee. It is a really scary time. Treatment programs are closing at an unprecedented rate. Meanwhile, overdoses are rebounding, suicides are rising and alcohol consumption increasing.

What effects of the pandemic are you observing in the people you serve?

I am seeing a lot of stress and strain in relation to with the people I am working with. I am not in a direct service role, so I am seeing the secondary impact that it is having on them. What I am seeing is consistent with what the literature says that people experience who undergo prolonged disasters and mass traumas. We really need to think of people in caregiver roles and pay particular attention to them. We need to care for our SUD care givers, we are really going to need them even more moving forward.

What, if any, long term effects do you anticipate on the field?

Around 230 Million dollars of federal money from the national opioid response has poured into my home state, yet little has gotten to the ground level and invested in ways that support our care infrastructure. Our workforce, who already labored under very difficult circumstances for low pay and with significant administrative burdens was in a perilous position. The untold story of the SUD service system workforce is that in the early weeks of COVID-19 they went to work, most often without proper protective masks and equipment. Some even lost their lives in the process. Burnout is increasing, compounded by the additional stressors created by COVID-19. We are watching our workforce wither and our care infrastructure crumble. There is no doubt that there will be long term consequences from what we are seeing unfold. The problem is that similar dynamics are playing out in other sectors of our healthcare system and as a result of negative public perceptions about addiction and recovery we are a low priority for policymakers. The truth is that it is not yet too late to turn this around. These two public health emergencies are linked because people are turning to drugs and alcohol for relief. We must save our care system and the workforce that is out in the field saving lives or it will be profoundly worse.

Have you seen any benefits or new opportunities in the pandemic?

This is an opportunity to reevaluate things and a chance to re-envision how we do things and consider reprioritizing. It is very clear to me that addiction is a central facet of the COVID-19 pandemic and underpins a lot of the challenges we face. It is very clear to me that we need to get serious about recovery and focus more resources on expanding recovery through access to care and support. One of the lessons of COVID-19 is that our service community is incredibly adaptable. Virtual Recovery Support Services (VRSS) are an example of this. Very few providers were conducting services using telehealth and web-based platforms, that changed quickly following the COVID-19 lockdown. We need to have a larger conversation on how and when to use these services. Our PRO-A VRSS Ten Assurances document is intended to get people thinking how they may be used. We also need to understand who gets left behind and work to ensure that these types of service are additive to our care system and we do not end up thinking about them as a panacea and send people exclusively to VRSS.

Talks about your project to improve treatment and recovery support, what would it be?

My long-term dream project is to move our care system towards a recover focused model that addresses the multitude of social, physical, emotional, housing, financial, and other co-occurring conditions/ issues. There is growing recognition that the benchmark for a substance use disorder recovery is an orientation towards a system focused on getting people to five years of continuous recovery. We must retool our service system to support this truth. What would this look like? It would be:

- A Substance Use Care Service System that supports long term recovery for five years

- A Service System that meets the needs of young people – early intervention and comprehensive care

- Build the 21st Century workforce to serve the next generation, properly trained and compensated

- A focus on Employment, Education, and Self-Sufficiency

- Recovery Housing Opportunities to support safe and ethically run housing for people who need it as part of their recovery process

We are pleased to announce the release of our newest Tips & Tools for Recovery that Works! video National Recovery Month.

Now in its 31st year, Recovery Month celebrates the achievements made by those living in recovery. The journey to recovery is not easy, but it is worth it, and SMART Recovery is proud to be a part of it.

Help us celebrate National Recovery Month by supporting SMART Recovery in our mission to ensure everyone gets the opportunity to live life beyond addiction!

Click here to watch this video on our YouTube channel

Subscribe to the SMART Recovery YouTube Channel

Video storytelling is a powerful tool in recovery, and we are proud to share our SMART Recovery content free-of-charge, available anywhere, on any device. Our videos hope to inform, entertain, and inspire anyone in the recovery community.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel and be notified every time we release a new video.

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

In celebration of National Recovery Month, Fellowship Hall will be highlighting the stories of some of our incredibly inspiring alumni and staff members on social media and here on our blog. It is our hope that in sharing these stories, we break the stigma surrounding drug and alcohol addiction. With knowledge, we can advocate for the proper treatment of ourselves and loved ones that may struggle with the disease.

***

What comes to your mind when you think of your High School experience? Do you think back to your early teens—walking halls lined with lockers and laughing after school with friends? Do you remember the deep desire to find your “place” among your peers — your need to fit in? Fellowship Hall Alumni, Trent C, recalls these years as the beginning of his life-long battle with substance use disorder.

“When I think back, I didn’t really have anything in my childhood that was traumatic, I had a good family, and a great upbringing,” Trent said. In ninth grade, he moved to North Carolina and began a new school where he knew no one. He explained that at that young age, he was insecure, lacked true decision-making abilities, and was only focused on “fitting in” with a social group, especially one that he perceived as the “popular” crowd. Unfortunately for him, the group of teens he found himself amongst were actively using and selling drugs. At just 15 years old, Trent was using, selling, and would go on to live this way until he was almost thirty.

Despite his use of substances, Trent earned an academic scholarship to the University of South Carolina. However, instead of focusing on his academics in college, he stayed chained to the same life he was living in high school — one wrought with partying and using. “My so-called ‘friends’ from high school were seemingly doing well, but they were all using substances, and using me to get them. In my mind, I felt like I had all these great friends because I was always invited to and going to the parties in college, but in reality, everyone was just using me to get what they wanted, and to feed their addiction. Truthfully, I was doing the same thing,” he said.

Trent said that neither losing his scholarship nor getting arrested was enough to motivate him to permanently change his ways. In fact, Fellowship Hall was the fourth facility he completed treatment at. Each time prior he was going to treatment to appease or serve others in his life — to keep his girlfriend happy, to “get his parents off of his back,” but never to truly get well.

“Unfortunately for me, it took a lot. There was no big huge rock-bottom moment or event that motivated me to turn my life around. I just woke up one day and realized I was almost thirty years old doing the same things I had been doing since high school. I thought to myself, ‘do you want to keep living like this for the rest of your life? Or do you want to actually do something about this?’ ”

During his t ime in treatment at the Hall structured days created stability where he formed lasting positive habits for himself such as daily meditation, prayer, physical activity, and going to meetings. He also attributed his success to his counselor.

ime in treatment at the Hall structured days created stability where he formed lasting positive habits for himself such as daily meditation, prayer, physical activity, and going to meetings. He also attributed his success to his counselor.

Trent became close to a guest who finished his treatment one week ahead of Trent. In the week while Trent was still in treatment, and his friend had discharged, his new friend returned to use and lost his life. That’s when Trent “broke through” and understood the severity of substance use disorder. “I realized this disease and these substances were killing people, they weren’t going to just go away, and that just one bad choice to use could end up being the choice that takes your life, and that ruins the life of the people who care about you.”

Today, at almost thirty, Trent enjoys the new life that recovery has given him. He focuses on staying spiritually fit, active in his recovery, and even active on the basketball court—he’ll happily tell you those afternoons spent playing basketball helped him make some of his favorite memories at Fellowship Hall.

Today, at almost thirty, Trent enjoys the new life that recovery has given him. He focuses on staying spiritually fit, active in his recovery, and even active on the basketball court—he’ll happily tell you those afternoons spent playing basketball helped him make some of his favorite memories at Fellowship Hall.

“This is MY recovery. I don’t know for sure that I’ll ever get another one. Once I understood that I had to submit and practice the honesty, open-mindedness, and willingness that we’re taught, it was easy for me. I began discovering myself after years of stunting my own growth because of this black hole inside me that I was filling with other things. My relationships with the people that are important to me are so much stronger and they can actually trust me again. I got my life back and I have confidence in myself now.”

Fellowship Hall is honored to be a place where our guests can find themselves and the confidence to be successful in their sobriety. Trent said that to those new to recovery, he wished to encourage them to understand that they cannot do it their own way, or alone, but if they are willing to submit, especially at Fellowship Hall, they can build a great foundation for their recovery and for the rest of their lives.

For more information, resources, and encouragement, ‘like’ the Fellowship Hall Facebook page and follow us on Instagram at @FellowshipHallNC.

About Fellowship Hall

Fellowship Hall is a 99-bed, private, not-for-profit alcohol and drug treatment center located on 120 tranquil acres in Greensboro, N.C. We provide treatment and evidence-based programs built upon the Twelve-Step model of recovery. We have been accredited by The Joint Commission since 1974 as a specialty hospital and are a member of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers. We are committed to providing exceptional, compassionate care to every individual we serve.

(This post was originally published on September 11, 2013)

I recently listened to an interview with Nadia Bolz-Weber. There were a lot of keepers in the interview (even for a non-believer). She’s described as a recovering drug addict. Her recovery shines through in this, “fake it till you make it” discussion:

Ms. Tippett: So a sermon of yours I wish I could have heard is “Loving Our Enemies Even If We Don’t Mean It.”

(laughter)

Ms. Nadia Bolz-Weber: Yeah, I think meaning it is overrated. I mean, I think …

Ms. Tippett: I think this is profound. I really do.

Ms. Nadia Bolz-Weber: No, I’m serious. Like, my gosh, if God’s going to wait till I mean it, that’s going to be a while, right? So I think that the key is praying for them, not like feeling warm feelings towards people who’ve hurt you or towards your enemy. I don’t think it’s about feelings. I think it’s about an action.

That was kind of neat, but what she said next really leapt out to me. [emphasis mine]

…I think that’s what the sort of love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you means. I will actually ask other people to do it for me sometimes, like it doesn’t always have to be us. And so it’s like this thing like I don’t think faith is given in sufficient quantity to individuals necessarily. I think it’s given in sufficient quantity to communities.

Wow. It reminds me of my persistent despair many months into my recovery and Dave H. telling me, “It’s okay if you don’t believe it’s going to get better, just believe that I believe it’s going to get better for you.”

This reminds me of an aha moment I had when listening to Bill White describe the recovery coaches of Project SAFE. I remember listening to him and thinking of the clients in those stories as having no protective factors–none!–only risk factors. He went on to describe the assertive support and engagement that these workers provided. I realized that these workers were becoming and creating protective factors in the lives of these women.

It also reminds me something my friend Ben often says, “Too often I fail to notice how much of the time I’m carried by others.”

What a gift it is for our profession to have access to a recovering community that, a group and one-to-one level, provides so much hope, faith and tangible support.

Lisa Gibson knows firsthand that losing a loved one to addiction is devastating. Her son Jay died in February 2018 after an alcohol-related brain injury. One source of consistent support for Lisa has been Jay’s many friends.

These friends immediately engaged in supporting the cause Jay’s family choose to highlight at the celebrations of Jay’s life in Brooklyn, NY, and Denton, TX: SMART Recovery. As a result of the outpouring of support, SMART Recovery suggested the creation of the Jay Gibson Education & Outreach Fund (Fund).

Since then, Lisa has traveled to see these friends in Denton and Brooklyn a number of times, including around Jay’s birthday last September. But, Lisa says, not this year:

This time it’s different, because of the pandemic. I’ve gotten together before with his friends in Texas and New York…I’m extremely discouraged that I’m not going to be with his friends this year.

The Fund has made a significant impact during this time of COVID-19 challenges. Much like Lisa’s current inability to get in-person support from Jay’s friends, many SMART Recovery participants are left without access to the support of in-person meetings. This has meant moving meetings online via the Zoom platform, with licensing and other costs.

The Jay Gibson Education and Outreach Fund has helped meet this critical need. In fact, there are now 70 meetings in three states that are operating through the end of the year directly because of the Fund. Thousands of people getting help, sharing their struggles, supporting each other. Lisa understands the great value that has been made possible by her tragic loss:

I think it’s a lifeline…people who are in recovery need that connection when cravings happen, that’s the beauty of the SMART meetings even before the pandemic.

You can make a donation directly to the Jay Gibson Education & Outreach Fund on the SMART Recovery website.

About SMART Recovery

SMART Recovery’s 4-Point Program® helps people recover from all types of addictive behaviors, including: alcohol abuse & addiction, drug abuse & addiction, substance abuse, gambling addiction, and addiction to negative activities.

SMART Recovery sponsors face-to-face meetings around the world, and daily online meetings. In addition, our online message board provide forums to learn about SMART Recovery and obtain addiction recovery support.

Visit www.smartrecovery.org to learn more.

Subscribe To Our Blog

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the SMART Recovery Blog.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

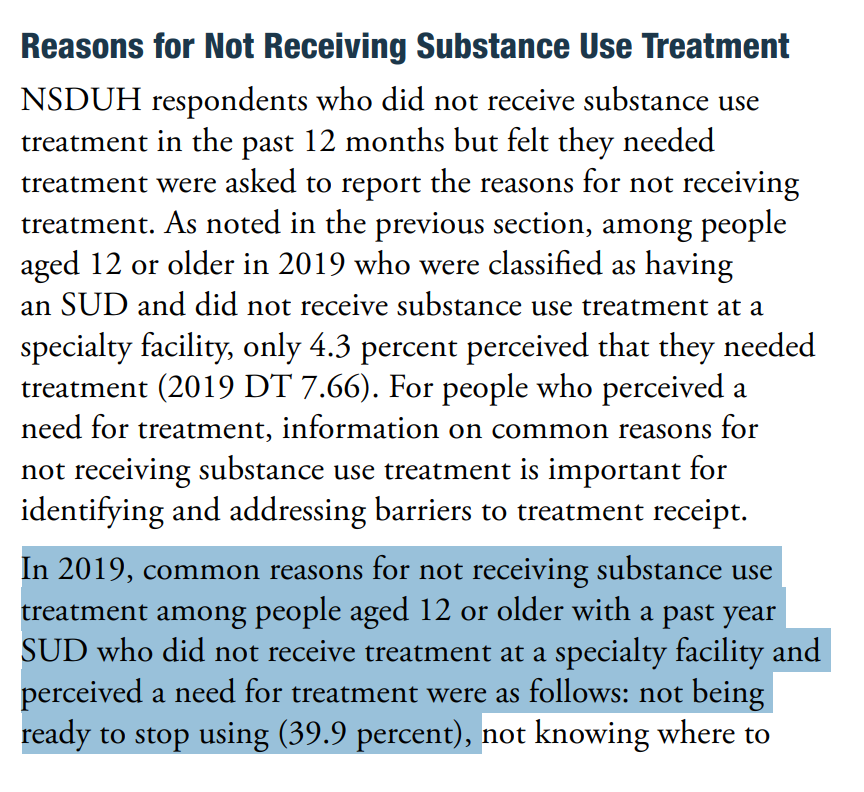

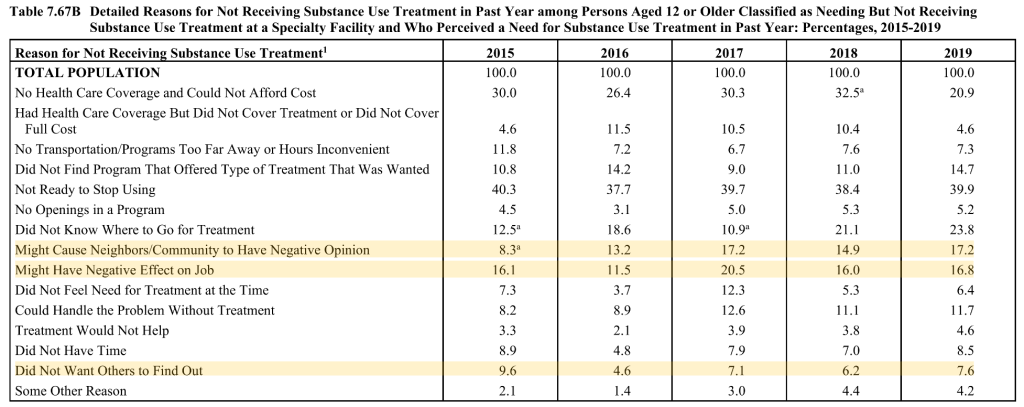

SAMHSA released the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Annual National Report this week.

One of the sections that’s gotten a lot of attention on Twitter is Substance Use Treatment in the Past Year.

The item that seems to have received the most attention is Reasons for Not Receiving Substance Use Treatment.

In particular, that the most common for reason for “not receiving substance use treatment among people aged 12 or older with a past year Substance Use Disorder (SUD) who did not receive treatment at a specialty facility and perceived a need for treatment were as follows: not being ready to stop using (39.9 percent)” [emphasis mine]

The concern is that the emphasizing this as the top reason for not seeking treatment reinforces myths and stigma about people with substance use problems.

Let’s break it down

“not receiving substance use treatment” – This finding is based on people who did not receive treatment. People who did receive treatment are not included. So, this does not represent people with an SUD, just people with an SUD who did not receive treatment in the past year.

“among people aged 12 or older” – This finding includes a very large age range. Let’s look at the sub-ranges included:

- Among adolescents aged 12 to 17 in 2019, 4.6 percent (or 1.1 million people) needed substance use treatment in the past year.

- Among young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2019, 14.4 percent (or 4.8 million people) needed substance use treatment in the past year.

- Among adults aged 26 or older in 2019, 7.2 percent (or 15.6 million people) needed substance use treatment in the past year.

So, respondents aged 12 to 25 make up 37.5% of those included in this statistic. A couple of things come to mind about this group. First, we would expect lower levels of readiness to change among this group. In the case of addiction (the most severe form of substance use problems) the time between the first use and the first help-seeking is typically 4 to 5 years. We also know that earlier onset typically results in longer addiction careers. Second, we know that more than half of people under the age of 26 with alcohol dependence will “mature out” or experience “spontaneous recovery” without treatment.

“with a past year SUD” – This invites questions about how SUD is defined.

The report says the following, “The SUD questions classify people as having an SUD in the past 12 months based on criteria specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV).”

The DSM-IV had 2 categories of SUDs–Abuse and Dependence. The diagnosis is substance-specific (e.g. – Cannabis Abuse, Alcohol Abuse, Opioid Abuse, etc.) and Abuse is the less severe of the 2 categories of disorders. The diagnostic criteria are as follows:

A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one (or more) of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

- Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home (e.g., repeated absences or poor work performance related to substance use; substance-related absences, suspensions, or expulsions from school; neglect of children or household)

- Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous (e.g., driving an automobile or operating machinery when impaired by substance use)

- Recurrent substance-related legal problems (e.g., arrests for substance-related disorderly conduct)

- Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance (e.g., arguments with spouse about consequences of intoxication, physical fights)

One of the criticisms of DSM IV Abuse what that the threshold was too low for categorizing it as a disorder. For example, a college student who gets convicted of Minor in Possession of alcohol and is put on probation, and later discovered to be drinking again would meet diagnostic criteria for Alcohol Abuse.

The report does not break down the prevalence of Abuse vs. Dependence among the respondents.

It’s also noteworthy that most people meeting criteria for DSM Abuse will not need to abstain to resolve their problem–most of them will moderate their substance use without any help. The report also points out that many people who meet criteria for dependence will not need treatment and many of them will also be able to moderate.

I believe that the combining of these people with others who have chronic and severe substance use problems into the category Substance Use Disorders renders the category meaningless. This is an unpopular view in advocacy circles.

“and perceived a need for treatment” – This invited questions about how perceived need was determined. The NSDUH used the following question, “During the past 12 months, did you need treatment or counseling for your alcohol or drug use?”

I imagine that asking people if they needed counseling at some time in the past year for alcohol or drug use significantly lowers the threshold for inclusion into the group with a “perceived need” for treatment.

“not being ready to stop using” – The concerns raised in multiple tweets by multiple advocates centers on 40% of people with an SUD and a perceived need for counseling or treatment not receiving treatment because they reported “not being ready to stop using.” [emphasis mine]

That response indicates an assumption that counseling/treatment requires abstinence from use of (at least) the substance in question. As mentioned above, abstinence is probably not a necessary or appropriate goal for most people meeting criteria for DSM IV Abuse and many people meeting criteria for Dependence.

So … this option could capture any respondent with low problem severity, high insight, and ambivalence about abstinence.

What’s the problem?

Does this finding misrepresent people with SUDs?

Does it reinforce stigma?

I don’t know whether it reinforces stigma and I can’t say for sure whether it misrepresents people with SUDs. However, this highlights a problem I’ve posted about several times–SUDs is not a useful category. (Bill Stauffer also posted about it here.)

I’ll go further–the use of this category harms people with addiction and may increase stigma towards them.

- This category results in the conflation of people with lower severity problems who “mature out” and people who have chronic, severe, and treatment resistant addiction.

- This category results in arguments that moderation is an appropriate goal for the category. It also results in arguments that abstinence is the only appropriate goal for the category.

- This category too often turns “maturing out” into an argument against the need for treatment.

- This category contributes to the erosion of the conceptual boundaries of addiction and recovery.

Overshadowing stigma?

Among the complaints that this reinforced stigma was another complaint that the grouping of responses obscured stigma, which should have been listed as the largest reason for not seeking treatment among people who perceived a need for treatment.

This argument is based on 3 reasons that seek to quantify stigma adding up to 41.6%.

Stigma is a significant barrier to treatment, but I suspect that 41.6% overstates the role of stigma.

- It seems safe to assume that 100% of “might cause neighbors/community to have negative opinion” selections represent stigma.

- “Did not want others to find out” seems a little less clear. A lot of people don’t want others to know anything about their health or personal life. However, that desire for privacy typically doesn’t prevent people from seeking treatment. So, it’s probably safe to assume that most of these responses represent stigma.

- “Might have a negative effect on job” seems much less clear. This could represent fear of stigmatization or it could represent concern about required recurring appointments that might interfere with work attendance.

- Finally, respondents were able to select more than one reason. (The responses total 193.4%.) It’s probably safe to assume there’s some overlap with these three responses.

None of this suggests that stigma isn’t a barrier to treatment or that it’s unimportant. (This blog has 188 posts with the word “stigma” going back to 2006.) I just believe the facts are compelling enough without having to inflate the numbers of people suffering or recovering. I also worry that stigma is so frequently invoked as an explanation for nearly every “problem” in the field that we are eroding the meaning and impact of the term. I believe that doing so will eventually erode our credibility. (I put problem in quotes because many problems in the field are in the eye of the beholder.)

I believe the problem with the reports about the NHDUH is not the the way it’s presented, but the use of this category that includes people making unhealthy decisions about their alcohol and other drug consumption and people with chronic and severe forms of the disease addiction. Imagine a report on “respiratory disorders” that treats common colds and lung cancers as belonging to a single category.

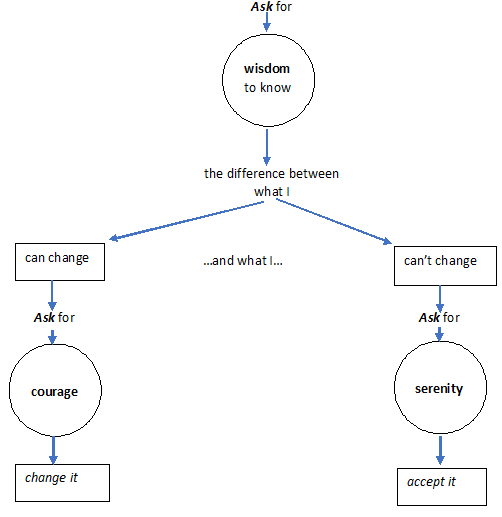

Action is in italics.

What one lacks is held in circles.

One asks for what one lacks.

Part of my job is teaching medical students about addiction and recovery, something I enjoy. Like others, I encourage future doctors to attend mutual aid meetings as part of their education. A couple of studies with this theme recently caught my eye.

In the first, 138 medical students attended an AA meeting and then wrote reflectively about the experience. The researchers found evidence that going to a meeting challenged students’ stigmatising attitudes and increased ‘flexibility of thinking’. They found younger students seemed to have fewer solidified biases.

In the second, medical students on a Family Medicine attachment attended a single AA meeting and again reflected on the experience. The researchers found that after being at a meeting, students were more likely to find AA a useful resource, were more likely to refer and felt more confident about explaining AA.

The researchers from both these studies state the value of the practice. In my experience, students rarely find mutual aid meetings dull. The power of the personal narrative can be compelling and evidence of altruism and mutual care is inspiring.

I suspect that such practices across the caring, support and therapeutic disciplines will have similar beneficial results and we should encourage all teaching settings in addiction treatment to embed this as part of their core delivery.

Since its inception in the late 1990s, a central goal of the new recovery advocacy movement has been assuring the representation of recovering individuals and families in the decision-making venues that affect their lives. As this movement matured, the complexities of achieving such representation became increasingly apparent. Dynamics within and beyond communities of recovery can threaten authentic recovery representation. Below are six critical dimensions of recovery representation and proposed benchmarks for each.

Authenticity of Representation is the assurance that those representing the recovery experience within decision-making venues are individuals and families with lived experience of recovery who are free from undue conflicts of interest. The problem that sometimes arises is that of double-agentry—persons who present themselves as representing the recovery community who, with or without conscious intent, represent instead personal, ideological, institutional, or financial interests. People with personal knowledge of the recovery process and the historical challenges faced by people seeking and in recovery free of such conflicted interests are the best suited for recovery advocacy leadership.

Guidelines: 1) Members of recovery communities are provided a voice in the selection of persons who represent their experiences and needs. 2) Those representing the recovery experience at public and policy levels possess rich experiential knowledge of personal and/or family recovery from addiction. 3) Persons representing the experiences and needs of people seeking and in recovery are free from ideological, political, or financial conflicts of interest that could unduly influence their advocacy efforts.

Depth of Representation assures a sufficient density of recovery representation within any decision-making group. The challenge is to avoid recovery tokenism, e.g., a single person asked to represent the broad range of recovery experiences and recovery support needs. Too many organizations exploit people in recovery to burnish their organizational image or superficially comply with an external recovery representation requirement, while affording little opportunity to affect policy decisions. Depth of representation also assures that people in recovery are at policy decision-making tables and not just involved in an advisory capacity, e.g., representation on governing boards as well as advisory committees.

Guidelines: 1) Recovery community organizations (RCOs) maintain authentic recovery representation greater than 50% at membership, board, and staff levels. 2) RCO leaders are drawn from individuals and family members in recovery or allies vetted by communities of recovery. 3) The RCO is committed to leadership development of its members. 4) Recovery representation in local organizational decision-making is commensurate with the degree to which recovery is central to the mission of an organization or project. The greater the focus on recovery, the greater the desired level of recovery representation.

Diversity of Representation assures the inclusion of people representing the growing varieties of recovery experiences and the diverse cultural contexts and community spaces in which recovery flourishes or flounders.

Guidelines: 1) The pool of available recovery representatives reflects secular, spiritual, and religious pathways of recovery as well as natural recovery and peer- and/or professionally-assisted recovery (including medication-assisted recovery). 2) Recovery representatives are knowledgeable about diverse communities of recovery and speak publicly not as individuals or representatives of one path of recovery, but on behalf of all people in recovery. (The fact that no one is fully qualified to do that helps us maintain a sense of humility, open-mindedness, and inclusiveness.) 3) Recovery representatives embody a spirit of anonymity—the suppression of self-centeredness—embracing and celebrating the wonderful varieties of recovery experience rather than competing for personal attention or pathway superiority. Falling short of these aspirational values is far too easy in the rarified air of public attention.

Stability of and Support for Recovery Representatives assures that people representing the recovery experience at the public level have sufficient recovery time and stability to offer a positive face and voice of recovery without threat to their continued recovery or their physical and psychological safety.

Guidelines: 1) Recovery representatives exemplify a recovery custodian orientation (rather than a celebrity orientation). 2) The custodian role properly places the focus on recovery messages and off the person or persons serving as messengers. 3) Recovery representatives exemplify servant leadership, affirming their role in serving the community. 4) Recovery representatives are not placed in roles involving physical or psychological risk without supervision and clear safety protocol.

Scope of Representation assures that people in recovery have a voice in shaping the full continuum of care related to alcohol- and other drug-related problems. Recovery representation is critical to effective AOD systems design, program implementation, service delivery, systems performance evaluation, and ongoing systems refinement.

Guidelines: 1) Recovery representation is included in policy and programming decisions related to primary prevention, harm reduction, early intervention, clinical treatment, community-based recovery support services, and the larger arena of alcohol and drug policy decisions. 2) Recovery representation is included in decision-making bodies charged with addressing common recovery challenges and resource needs, e.g., co-occurring health conditions, educational opportunity, employment opportunity, etc.

Public Enfranchisement assures that people in recovery are free from arbitrary restrictions on voting, holding public office, or exercising rights afforded other citizens.

Guidelines: 1) Local recovery community organizations exist and advocate for the full enfranchisement of people in recovery, including encouragement to vote and serve in public service roles. 2) People in recovery disenfranchised due to past addiction-related crimes have their full citizenship rights restored following release from prison or completion of probation or parole. 3) There are no state or local laws or regulations that otherwise suppress the voting, e.g., statutes requiring all fines be paid before voting rights are restored. 4) The addiction treatment and recovery support workforce fully reflects the diversity of the community, is provided a living wage, and is free of administrative burdens that interfere with service provision. 5) The treatment and recovery support system addresses barriers to employment and volunteer participation of people with lived experience of recovery.

Closing Reflection

Supporting and strengthening long-term recovery across multiple pathways of recovery and diverse cultural contexts must remain a central focus of our efforts. This is “the commons” of our movement for which we need deep, equitable, and inclusive representation in matters that effect our lives.

Nihil de nobis, sine nobis is Latin for NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT US and has been a rallying cry for democracy and disenfranchised groups for over 500 years. It means that no policy should be decided without the full and direct participation of those affected by that policy. We must ensure that our voices are included in all systems addressing alcohol- and other drug-related problems.

Link to Bill White Article HERE