When I entered full time clinical work back in 1988, I entered the primary SUD (vs primary MH) side of a relatively large community agency with dozens of units and specialty programs spread across the city, and a dedication to innovative services.

One of those innovative programs was a 24/7/365 mobile crisis intervention program called the “Emergency Response Service”. It opened there decades ago as one of the first of its kind in a national demonstration project and is still in operation. That program had master’s level MH clinicians that were also deputized, and had specially equipped cars and police radios (but no handcuffs). They respond to psychiatric emergencies. Calls for help come from individuals or families in the community, and they can also be dispatched directly by the local police department. When ERS clinicians arrive, the police often stay if and as needed and let ERS take the lead, or other times simply leave. ERS clinicians regularly attend police shift change meetings. The police and ERS have worked in a partnership in that city for decades.

My clinical work was on the SUD side of the organization. After my first year in a Minnesota Model residential 28-day primary SUD program, my work moved elsewhere in that agency, to a 1-year residential program that was a traditional therapeutic community (TC). It shared a staff and physical plant with a methadone maintenance (MMT) program. I learned both models, worked in the TC for 7 years and in that time learned a lot about methadone maintenance – after all, the building and staffs of the two programs were shared. After that first 7 years I worked both the TC and MMT programs simultaneously another 12 years.

- Early on in my experience we were exposed to Motivational Interviewing when it was relatively new. We adopted it in our methadone maintenance program and in our TC, which was no small change. Confrontation started to change dramatically and eventually went away. MI and MET became our operating system.

- Later we added a nursery component with space for infants up to age 12 months to live with their mothers during residential treatment.

- We were exposed to and adopted gender specific programming when that became best practice.

- Later, CSAT sent out an RFP for a Federal demonstration grant for enhancements of existing pregnant/post-partum parenting women’s residential SUD programs. We were funded1 for expansion of our in-house services and went up to a dozen children up to age 4, built on a new wing to the building, and added a dedicated nursery staff, and more. That grant included special competencies in gender-specific and culturally relevant care.

- Later, we were exposed to the Consumer-Centered model when it was unheard of in primary SUD services, and adopted that – another huge paradigm shift and set of changes.

- Later we were exposed to Consumer-Driven models and related clinical practices and adopted that approach over Person-Centered methods. By then our residential TC model and clinical practices had changed dramatically.

Later yet, our organization became a living laboratory for the Behavioral Health Recovery Management (BHRM) project2. Recovery Orientation (e.g. “study recovery and have that inform treatment”) was a revolutionary set of changes to say the least. Eventually, the BHRM principles were codified. We led further changes across our entire organization by innovating deliberately within our existing clinical models (consumer-driven, gender-specific, and specific best practices within each service) according to the BHRM principles. These resulting changes were specific and vast. Meanwhile, the leadership’s dedication to adopting best clinical practices, sustained fidelity to those practices, and best principles and practices for leading and guiding organizational change was paramount and sustained for many years.

Along the way, looking out the back windshield so to speak, I noticed treatment models I was originally trained in (and that we replaced) were later derided. And later yet, the replacement models were themselves replaced and derided. I saw this continue to happen. New models of thinking and practice would be adopted and the existing practices (once revolutionary, challenging, new, and best) would later be derided. I noticed derision seemed most sharp for those practices that were further away in time. And I noticed sharper derision was likely to be from those that never experienced the older practices they were criticizing, and certainly never as a breath of fresh air when those innovations first arrived.

Lately, I notice what to me seems another new shift. This change is in the field overall. To me it seems to be one shift with three aspects: being, purpose, and knowledge.

I’ll outline the shift by breaking down those three aspects in the form of first-person statements.

A. “I don’t need a person with letters, or recovery, or their own story, to tell me who I am.” (ontology; being)

B. “I don’t need a person with letters, or recovery, or their own story, to tell me what to do.” (teleology; purpose)

C. “I don’t need a person with letters, or recovery, or their own story, to understand me.” (epistemology; knowledge)

I wrote those in a more pointed way with a certain degree of emphatic clarity just to promote their consideration. Interestingly, those three points of emphasis seem to correspond with 3 aspects of our field. I’ve built a continuum from older (on the left) to newer (on the right) for each.

It seems we now have the following:

Recovery……………………………………..Liberation

- Who I Am (e.g. person with SUD)

- You tell me………………………………..I tell you

- Who you are (e.g. other person in the room)

- You tell me………………………………..I tell you

Abstinence…………………………Harm Reduction

- What to do (e.g. person with SUD)

- You tell me………………………………..I tell you

- What to do (e.g. other person in the room)

- You tell me………………………………..I tell you

Treatment……………………………….Peer Support

And we eliminate knowing and the attachment to knowing (e.g. the mutual sharing of knowing and what is known). For either or both persons, “knowing” will not be stable and will flow. At times, knowing may seem to emerge, to disappear, or a void in knowing may manifest. Regardless, all knowing is viewed with skepticism and held lightly because “knowing” shifts.

This is interesting to me, as I remember when “Traditional Model” was all there was, and “Recovery Model” (on 16 dimensions) was the new and revolutionary point of contrast. What I am framing here might be old-hat to some, and shockingly new to others. I’d like to emphasize the relatively profound set of changes it holds and opportunity it represents.

1Godley, S., Funk, R., Dennis, M., Oberg, D. & Passetti, L. (2004). Predicting Response to Substance Abuse Treatment Among Pregnant and Postpartum Women. Evaluation and Program Planning. 27: 223-231.

2Kelly, J. F. & White, W. L. (eds.). (2011). Addiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research and Practice. Springer: New York.

Mandy De Wolf learned about SMART Recovery after reading Sober for Good, and it changed her life. She completed the Get SMART Fast Training Program and now facilitates several online and face-to-face meetings. Watch as Mandy shares how she benefits from being a facilitator and why she’s proud to be part of the SMART community. […]

Mandy De Wolf learned about SMART Recovery after reading Sober for Good, and it changed her life. She completed the Get SMART Fast Training Program and now facilitates several online and face-to-face meetings. Watch as Mandy shares how she benefits from being a facilitator and why she’s proud to be part of the SMART community. […]

“I struggled with alcohol 24/7. It was in my blood,” Karen says. In her 50’s she decided enough was enough, but traditional programs would not do for this self-proclaimed numbers person. Then she found SMART Recovery. “The stats, facts, and science resonated with me. I realized I’m not powerless. I have the power within me.” Karen was introduced to SMART Recovery in 2014 while participating in an […]

“I struggled with alcohol 24/7. It was in my blood,” Karen says. In her 50’s she decided enough was enough, but traditional programs would not do for this self-proclaimed numbers person. Then she found SMART Recovery. “The stats, facts, and science resonated with me. I realized I’m not powerless. I have the power within me.” Karen was introduced to SMART Recovery in 2014 while participating in an […]

For some reason, summer always strikes me as a tough season to stay sober. Maybe because of the energy it brings, or the increased number of cook-outs and drinking that goes on. Granted, I didn't need the summer excuse to get my drink on, but I'm certain I used it anyway. If you are new to sobriety, or if you're like me and get a little nostalgic, here are 10 tips for a sane and sober summer.

JAMA has an article on cognitive bias as it relates to public health policy for COVID-19.

These cognitive errors, which distract leaders from optimal policy making and citizens from taking steps to promote their own and others’ interests, cannot merely be ascribed to repudiations of science. Rather, these biases are pervasive and may have been evolutionarily selected. Even at academic medical centers, where a premium is placed on having science guide policy, COVID-19 action plans prioritized expanding critical care capacity at the outset, and many clinicians treated seriously ill patients with drugs with little evidence of effectiveness, often before these institutions and clinicians enacted strategies to prevent spread of disease.

The article examines four cognitive errors: Identifiable Lives, Optimism Bias, Present Bias, and Omission Bias.

What makes articles like this so interesting is that cognitive biases are generally unknown to the people that hold them. This article is like an attempt to pull back the curtain on hidden influences of what we notice, how we define a problem, how respond to a problem, and how we evaluate that response.

I don’t know whether these biases were at play in COVID policy, this isn’t an empirical matter, but it seems like a credible argument. (We could say that this policy is consistent with that cognitive bias, but we can’t really know the contents of someone else’s mind.)

This got me wondering what cognitive errors are present addiction and recovery treatment and advocacy.

I like this frame because it opens up an exploration of disagreements that gets us away from character and opens the door to the idea that we all operate from cognitive errors that are invisible to us. That being the case, we need others to help us become aware of them.

If this is true–that we all operate from cognitive biases, that they are unknown to us, and we need others to help us see them–then we ought to be thoughtful about how we engage others, right?

- First of all, a cognitive bias isn’t evidence of bad motives, bad faith, or bad character.

- Second of all, our field has been big on motivational interviewing with the knowledge that confrontation evokes resistance. We expect each other to integrate this knowledge into our work with with clients, we probably ought to integrate it into our work with each other.

- Third, if we’re both capable of unknown bias, then the goal should be to examine our thinking to identify any hidden bias. (Of course, I’m focused on your error and want you to see it, but I should be aware that I’m likely to have some of my own.)

- Finally, if I need people who see things differently to identify my own biases, alienating people who disagree with me or shutting them down is a sure way to perpetuate blindness to my own cognitive errors.

This Lincoln quote comes to mind:

When the conduct of men is designed to be influenced, persuasion, kind, unassuming persuasion, should ever be adopted. It is an old and a true maxim, that a “drop of honey catches more flies than a gallon of gall.” If you would win a man to your cause, first convince him that you are his sincere friend. Therein is a drop of honey that catches his heart, which, say what he will, is the great high road to his reason, and which, when once gained, you will find but little trouble in convincing his judgment of the justice of your cause, if indeed that cause really be a just one. On the contrary, assume to dictate to his judgment, or to command his action, or to mark him as one to be shunned and despised, and he will retreat within himself, close all the avenues to his head and his heart; and tho’ your cause be naked truth itself, transformed to the heaviest lance, harder than steel, and sharper than steel can be made, and tho’ you throw it with more than Herculean force and precision, you shall no more be able to pierce him, than to penetrate the hard shell of a tortoise with a rye straw.

Such is man, and so must he be understood by those who would lead him, even to his own best interest.

Abraham Lincoln speaking to the Washington Temperance Society

Photo: Rally in the Valley, 2018 – Allentown PA

In early recovery many years ago, one of the things I was most impressed was the diversity of people who welcomed me into recovery. I observed bikers next to corporate executives and grocery store clerks talking with engineers about our common purpose, recovery. It got me thinking about big tent recovery.

The reality for many of us in recovery was that our personal politics, religious or other beliefs were a far distant second to this thing that brought us together. For many of us, this common bond of recovery was then and remains our collective lifeline. We dared not let those other things interfere with that which brought us together in common bond. I suspect as a result, may of us also learned about each other and grew to respect how we have had vastly different experiences and perspectives. Having spent a whole lot of time in rooms with people who did not look like me or come from similar backgrounds, I know I did.

Addiction and recovery from addiction is a complex, long term process that varies from person to person along as many individualized pathways as there are people on the journey of recovery. As addiction impacts every facet of life, recovery also involves and relates to a myriad of other social challenges. What at the heart of what recovery community advocacy are we focused on? The answer to this question is going to vary community to community. Developing a deeper understanding of how we approach the answer may assist us in staying focused on our core mission.

To the best of my understanding, the core focus of recovery advocacy is on expanding the number of people who can obtain and sustain long term recovery in all its diversity. It is the focus that has resonated with groups focused on traditional treatment, recovery support services, recovery high schools, collegiate recovery programming and recovery housing needs to name a few. All of these elements and more are needed to develop a long term, recovery focused care model in which recovery is the probable outcome for everyone.

We must have a deep understanding of where we came from to understand where we are going if we are to remain on the right track to get there. In 2001, recovery community organization leaders from across the United States come together in St. Paul Minnesota for a historic summit tied to the birth of this new recovery advocacy movement. The three goals that started out what we know call the new recovery advocacy movement were:

- To celebrate and honor recovery in all its diversity,

- To foster advocacy skills in the tradition of American advocacy movements and

- To produce principles, language, strategy and leadership to carry the movement forward.

Have we stayed true to those goals? Are they still the right goals? How do we stay in our lane? I do not pretend here to have the answers. I can tell you that the recovery movement I want to be a part of fosters big tent recovery – everyone is welcome without regard to any other belief or value. I personally think our common welfare depends on fostering a place where it does not matter what color hat you wear, red, blue or some other color. Religion or lack thereof does not matter, pathway to recovery does not matter. You want recovery, you are welcomed. That is all that matters. Big tent recovery.

Decriminalization of drugs, social justice, basic human rights are all issues of deep, substantive concern for so very many of us, but are they our central focus? To what degree if any do we incorporate other issues of broad concern? What is in our “lane” and what is out of our “lane”? What do we risk if anything if we expend our energy on these other issues? I am not sure. But what I can tell you is that it does matter to me profoundly that we stay true to a common purpose and that purpose remains stronger than issues that would otherwise pull us apart.

To find an avenue for overcoming alcohol misuse, Shelly Parr recalls she “Googled ‘nonreligious alcohol help’ and SMART was the first thing that popped up — thank goodness.” That was more than six years ago. Since then, Shelly has embraced the power of choice afforded her by SMART Recovery. “I got my old life back and a whole lot […]

To find an avenue for overcoming alcohol misuse, Shelly Parr recalls she “Googled ‘nonreligious alcohol help’ and SMART was the first thing that popped up — thank goodness.” That was more than six years ago. Since then, Shelly has embraced the power of choice afforded her by SMART Recovery. “I got my old life back and a whole lot […]

A question has been on my mind for a while–what is the place of morality or moralizing language in addiction and recovery?

Not moral?

Bill White has been one of the most influential recovery advocates of the last quarter century. One could argue that, over that time, no one has done more to advance the organization of people and institutions around the goal of stigma reduction.

In pursuit of stigma reduction he’s passionately challenged dehumanizing drug users and the moral model as a causal explanation for addiction. He’s also explored and exposed the consequences of these models. He was also a pioneer in challenging commonly used language as stigmatizing.

All of this is true AND he frequently discusses addiction and recovery in unambiguously morally laden language.

On the mirror faces of addiction and recovery:

Recovery must be as morally redemptive as addiction is morally corrupting, as connective as addiction is alienating. Recovery must be the Janus face of addiction, offering degrees of retrieval for past losses. Daily acts of addiction erode and degrade; daily acts of recovery restore and upgrade. Addiction and recovery involve mirror processes of character deterioration and character reconstruction.

On what he learned in detox:

Here’s what I learned in detox that no other level of care provided with such clarity.

1. Addiction is filthy. It soils the body and soul, shrouding the human being behind a mask of repulsiveness that would challenge a mother’s love.

2. Addiction is profane. It transforms the meek into the brash and obscene.

3. Addiction is poison. It poisons body, mind, and character. . . . Addiction deforms character and fuels hatred, jealousy, resentment, rage, and self-pity.

4. Addiction is anguish. A level of despair is expressed at a level of honesty within detox that is rarely seen in other settings.

5. Addiction is unredeemable shame. In detox, raw feelings of shame and self-hatred pour from the addict, revealing the existential position: I am unworthy of the love of others; I am unworthy of recovery.

6. Addiction is about isolation. It destroys the connecting tissue that binds the addicted person to their parents, siblings, intimate partners, children, friends, and co-workers. No one is as utterly alone as the man or woman walking into pained consciousness in their first day in detox. There is no “we” in addiction.

7. The addict in detox is a Mr. Hyde that transforms into Dr. Jekyll in the transition to other levels of care. Staff working exclusively in detox have only a glimmer of the Dr. Jekyll; staff working exclusively in inpatient and outpatient treatment see only a shadow of the deranged Mr. Hyde.

From: Recovery Rising

On the self in addiction:

The addiction process so empties some of us that we cease being a person. Having lost any semblance of boundaries, hugging us is like trying to hug smoke. Only a masked ghost of our former selves, we exist only as a drug-consumption machine dragging along whatever whisper of our former self that remains. We devolve to a simple organism that has only one function in life—to seek and consume the elixirs that are now the center of our existence. We can no longer assert or protect the self except in service to the drug. The self is empty and its psychological boundaries are now permeable and invisible.

I’m confused!

These apparent contradictions have left me confused.

I tend to think of stigma reduction as an effort to eliminate moral frames. This use of moral language places him outside of the zeitgeist, which is very odd, because he’s a major contributor to the zeitgeist.

My sense is that there are important truths in the efforts to refute the moral model and his insistence on using morally laden language to discuss the consequences and experience of addiction.

So . . . my take has been that this is a dialectic (thesis and antithesis) and I’ve wanted Bill to deliver synthesis for me.

I’ve asked him about it and haven’t gotten a response that really clarified the matter for me. It’s clear that he’s rejecting moral language to explain the causation of addiction, but he seems to assert moral language when discussing the personal and interpersonal consequences of addiction.

As I’ve started to infer this assertion of a moral dimension, I’ve modified my question to “what would be lost if we dropped this moral framing?” I still didn’t get what I was looking for. (Poor Bill. I’m a pretty concrete person. Bless him for his patience.)

Secondhand smoke, moral sanctions and COVID-19

I stumbled onto this article about the behavior changes required to reduce COVID-19 transmission and what we might learn from behavior changes around smoking.

The author recalls the days when it was normal to smoke in classrooms, airplanes and restaurants. He muses about how those norms changed within a generation.

The answer, I think, is that research on secondhand smoke took an individual (perhaps foolish) choice and moralized it, by emphasizing its effects on others. It was no longer simply dumb to smoke; it was immoral. And that changed everything.

Psychologist Paul Rozin has studied the process of moralization. When activities get moralized, they move from being matters of individual discretion to being matters of obligation. Smoking went from being an individual consumer decision to being a transgression.

He goes on to link this to behavioral obligations to reduce disease transmission. (Masks, for example.)

This got my attention off the person with addiction and onto the harm addictive drug use does to others.

Moral obligations in addiction?

This movement from individual discretion to a moral obligation got me thinking about what obligations people with addiction have.

I am a father, husband, son, neighbor, employee, teacher, community member, etc. All of these roles involve others. My mental status, my wellness, my focus, etc, all affect my performance in those roles and, therefore, affect others. I have obligations to them.

It is the hope (and sometimes the delusion) of many people with addiction that they are only harming themselves. Unfortunately, no person is an island, and it’s just not so.

Of course, some obligations are great and others are small. Some people are more affected than others, and the impact will vary widely. Some role failures can be devastating to others, while other role impairments may be an annoyance, inconvenience, or imposition.

So . . . if I have a treatable cancer that impairs my ability to fulfill my obligations to my children, do I have a moral obligation to treat it and try to get well? I believe I do.

Is that contingent upon it being a physical illness? I don’t think so. I’ve suffered from severe depression earlier in my life. (I had no idea how it affected others.) If I had a recurrence and it affected my ability to care for my children physically, emotionally, and financially, would I have a moral obligation to treat my depression and try to get well? I believe I would.

Is it a moral obligation failure if the treatment fails? No.

Is it a moral obligation failure if I don’t accept treatment? I think so. (Symptom severity may mitigate this.)

Does my moral obligation require that I accept only one treatment plan (pathway) selected for me by others? No.

It’s worth noting that whether I had any responsibility in the development of illness isn’t at issue and would be irrelevant.

What would we lose?

So . . . I’ve gotten my head around a place for morality in discussions of addiction and recovery. But, when the moral model of addiction has caused so many problems, why preserve a moral dimension at all?

Here are my initial, undeveloped thoughts:

Discussions about moral obligations in the context of addiction usually focus on social obligations to addicts. I believe society has moral obligations to people with addiction (and I believe we fail to meet those obligations), but to stop there infantilizes addicts and denies them agency.

A colleague in an adolescent program once said, “you can view these kids as victims, predators, or resources.” Denying their agency leaves them as victims rather than resources.

Addiction does real damage to family, friends, community, etc. Restoration of people with addiction requires acknowledging that damage. Even if one questions the addict’s responsibility for those harms, humans seem to be wired in a way that requires acknowledgment of harms done, an expression of remorse, lessons learned, and an offer of accommodation (amends). Eliding this damage at an individual or cultural level would approximate gaslighting.

Finally, Bill’s focus with this language is often on what addiction does to the self–to their character and their capacity to connect with and maintain reciprocal, growth-fostering relationships with others. If we fail to acknowledge that we risk capping their growth and the “return to self” and “better than well” experience.

I haven’t posted for some time.

The hospital I work at was hit very hard by COVID-19 and I’m still working on getting recharged for activities like blogging, but the pandemic did play a role in inspiring this post.

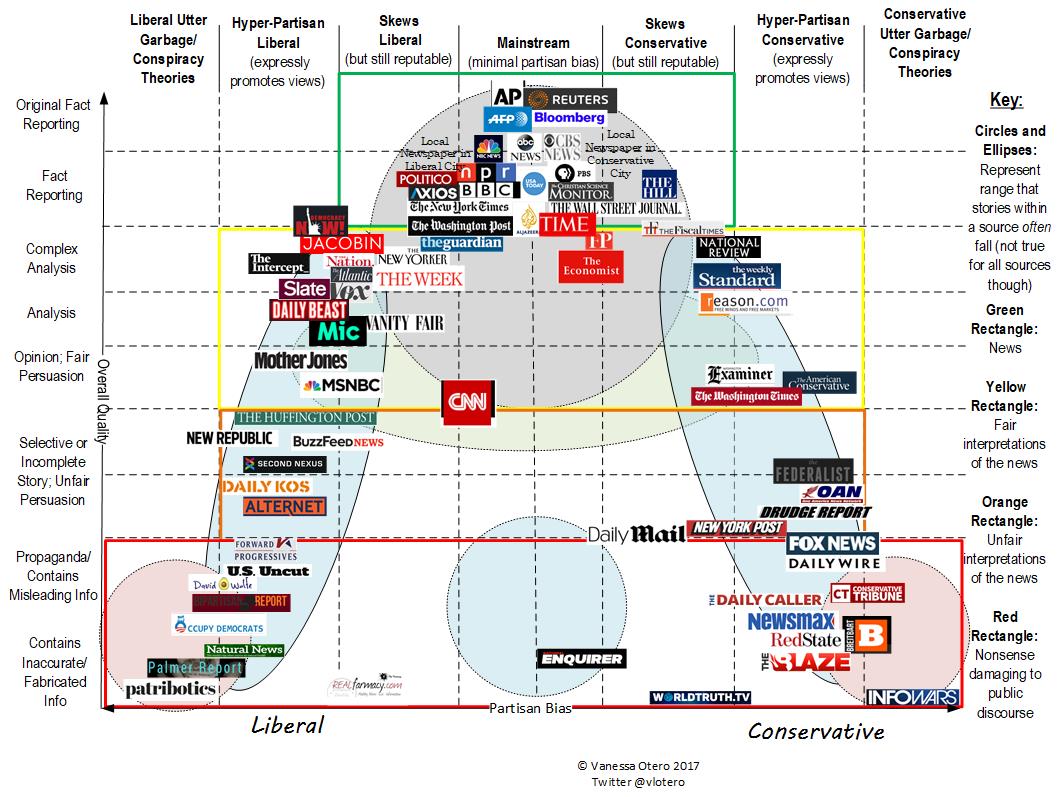

I’ve been thinking a lot about the convergence of several cultural trends:

- historically unprecedented access to information;

- the atomization of media and information sources;

- the tribalization of media and information sources;

- scientism as a cultural force that:

- lacks epistemic humility;

- is often dismissive of experiential knowledge;

- is often dismissive of outcomes that can’t be easily quantified and measured;

- faces a replication crisis;

- a crisis of faith in expertise and experts;

- an epistemic crisis creating a cultural inability to agree on facts (not the meaning of the facts, but the basic facts themselves);

- postmodern destabilization of traditional concepts and models, including addiction and recovery; and

- a cultural moral realignment from moral impulses like sanctity, authority, and loyalty to fairness and care.

How do these larger trends affect addiction, recovery, and treatment?

This is not an argument for or against anything, just a collection of observations as I’m trying to make sense of the pull and push forces affecting the field for better and for worse.

Information overload

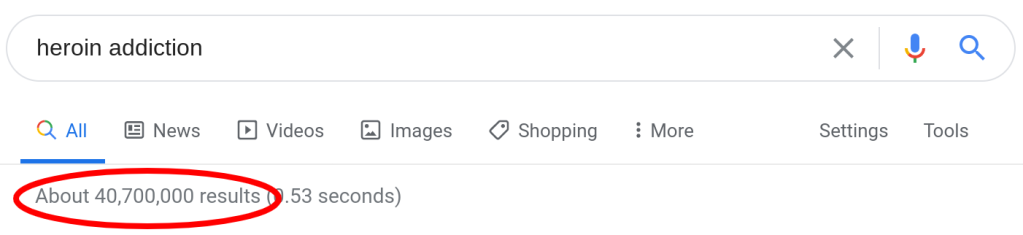

20 years ago, getting information on heroin addiction would require speaking with a doctor or counselor, or visiting a library. Today, in 0.53 seconds, one can have access to more than 40 million web pages about heroin addiction.

Atomization of information

Access to information is a good thing, but how does one begin to approach 40 million units of information?

It’s unapproachable. And, if one of those pages is yours, how do you distinguish yourself and find an audience?

This sea of information is going to be segmented by author, audience, style, etc. Furthermore, this isn’t one unit of information repeated in 40 million places with differences in the way or place it’s presented. The internet and social media has made it possible for everyone to create content. This information itself varies widely in focus, depth, and accuracy.

This is what I’m referring to as atomization–one topic generating 40 million units of information and those units being spread and sorted across millions of information sources.

Tribalization of information

As information gets atomized, some of it might sort by audience–for example moms, kids, healthcare providers, etc. Other sorting will be focused on advancing one ideology or perspective, often at the expense of another.

This is where we get into medication vs. drug-free, 12 step vs. CBT, abstinence vs. harm reduction, medical vs. psychosocial, etc.

As information gets sorted by these tribes, actors create their own content for their own tribe. Information sources become trusted not because of their rigor and accuracy but because of their fidelity to the messages/goals/values of the tribe. This elevation of fidelity to the cause over truth results in echo chambers and feedback loops that are increasingly unmoored from truth and isolated from conflicting information. These echo chambers increase tribalization by elevating the most extreme voices and escalating tension with other tribes through misinformation, straw men, and attribution of bad motives.

Scientism

While there’s no single definition of scientism, it generally refers to “the idea that all forms of intellectual inquiry must conform to the model(s) of science in order to be rational.” The term is often used pejoratively when science is invoked to dismiss an argument or position.

The premise that science can answer all questions sets up a few conflicts.

- If science can answer all questions, science can tell us what to value. Values that are not rooted in science can only lead us astray. They have no place in decisions about policies or treatments for addiction.

- Science values what can be measured and tested. It favors outcomes that can be easily quantified and measured. Abstract outcomes like “better than well” and outcomes that take years to evaluate are dismissed by scientism.

- Science-based arguments can often be constructed to support more than one position, including conflicting positions.

- Invocations of science often (knowingly or unknowingly) conceal values behind policy or treatment positions.

- Experiential knowledge is dismissed as anecdotal and invalid.

Moreover, medicine and the social sciences are facing a replication crisis that is unacknowledged by many advocates and used by others as a reason to dismiss scientific knowledge all together. One would hope that this would lead to epistemic humility, but seems like too great a hope.

A crisis of faith in experts

I recently heard a few relevant observations:

- Too many people think expertise means having a lot of information about something. And, as noted above, people have unprecedented access to information today. Having information does not make one an expert. Expertise is information plus experience.

- Experts (and politicians) are expected to have answers to questions that no one has answers for. We punish them for not knowing and then seek people who will provide an answer.

- Martin Gurri noted the following about COVID-19, “The experts, the people who knew the most, didn’t know that much, but they had to pretend that they did. And, that’s where you get in trouble.”

Epistemic crisis

This crisis of faith in experts (and the other trends) creates the conditions for an epistemic crisis, which David Roberts described as a split “in who we trust, how we come to know things, and what we believe we know — what we believe exists, is true, has happened and is happening.”

Similarly, Martin Gurri described the 21st century as post-truth, “as I define it, signifies a moment of sharply divergent perspectives on every subject or event, without a trusted authority in the room to settle the matter.”

This is a larger cultural phenomenon with disputes about whether there are caravans of foreigners entering the country, whether voter fraud is a widespread problem, and whether COVID-19 is under control.

In our space we see arguments about whether 12 step programs are effective, whether MAT is effective, the dangers of various drugs, whether one can OD on fentanyl by touching it, whether opioid prescribing had anything to do with the opioid crisis, whether moderate use is an appropriate goal for people with addiction, etc.

The explosion of information has eroded deference to experts by providing a platform for dissident experts, and exposing intentional and unintentional misinformation from experts. The internet and social media has also provided a platform for anyone to claim expertise. Expert status used to be a result spending time in institutions learning and practicing. These institutions were formative–they molded people. The new information landscape allows people to claim expertise outside of these institutions. It also allows people who have not yet been molded by an institution to use an association with the institutions to promote themselves.

It’s worth noting that our field has its own history of experts overstating the harms of many drugs, the prevalence of some drugs, over-extending the concept of addiction, and over-diagnosing addiction (particularly in young patients).

Destabilization of shared concepts

All of the above create the conditions for not just instability in our ability to determine or agree upon what’s true, but whether our underlying assumptions are true. Whether things like addiction and recovery are just social constructs.

For example, recent years have witnessed questions about:

- Whether addiction is a valid concept, or whether it’s chaotic use related to trauma and/or environmental conditions.

- Whether addiction is a prerequisite for recovery.

- Whether most of the harms associated with “addictive” drug use are due to it’s social and legal status.

- Whether “recovery” can include use of alcohol, tobacco, or non-prescribed use of substances with addiction potential.

- Whether definitions of recovery even need to address alcohol and other drug use.

Moral realignment

Realignment might be too strong a word here, but let me explain what I’m thinking.

Jonathan Haidt’s moral foundations theory suggests that there are 5 (or 6) universal moral impulses underlying the moral systems of every culture. The 5 (and the proposed 6th) moral impulses are:

- Care/harm

- Fairness/cheating

- Loyalty/betrayal

- Authority/subversion

- Sanctity/degradation

- Liberty/oppression

They believe everyone values each impulse to some degree but values some more than others. (It’s worth noting that a moral impulse can be expressed in a broad range of ways. For example, sanctity may be expressed as sexual purity or as eating “clean.”)

They’ve also proposed that political ideology predicts the moral judgments. Liberals tend to emphasize the Care, Fairness and Liberty dimensions (characterized as individualizing); conservatives the Loyalty, Authority and Sanctity dimensions (characterized as binding).

While political power is unstable and shifting frequently, it could be argued that liberals are winning the culture and that this is resulting in a increasing cultural emphasis on care, fairness and liberty while diminishing loyalty, authority and sanctity.

This invites the question, how does this affect beliefs about drug use, addiction, recovery, and drug policy?

Follow the science!

One of the things that brought this post to mind watching the coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic unfold. It seemed like an opportunity to restore faith in experts and institutions. Unfortunately, we watched a lot of these patterns repeat themselves.

One of the refrains I heard frequently was “follow the science!”

I hear this a lot in addiction treatment and recovery too. I find it frustrating. Not because I don’t value science, but I find that a useless statement.

My response is, “follow the science to what?”

Science can help us understand what is and what is possible, but it can’t tell us what endpoint to want. And, the trends above will shape our understanding of the problem(s), the solution(s), the good, etc.

For example, with COVID-19, the question may be, “what course of action would result in the fewest deaths and is medically, socially and economically sustainable for up to 18 months?” In the case of addiction treatment, the question may be which treatment will “get me back to the way I used to be” or “help me have a normal life with a job, a house, kids, friends and family.”

Science can provide valuable data and clues to help us achieve our goals, but it can’t answer many of the questions that are most important to us.

Unfortunately, conversations about these questions and the trends that shape the discussion do not lend themselves to social media posts.

Charles True has been building the kind of life he doesn’t want to relapse from for many years. His project work has taken him around the world including China, Russia, and the United Kingdom. One of his most impactful projects is the InsideOut® program. InsideOut is a cognitive-based therapy (CBT) program for substance abuse treatment […]

Charles True has been building the kind of life he doesn’t want to relapse from for many years. His project work has taken him around the world including China, Russia, and the United Kingdom. One of his most impactful projects is the InsideOut® program. InsideOut is a cognitive-based therapy (CBT) program for substance abuse treatment […]